Abstract

CUPSAT (Cologne University Protein Stability Analysis Tool) is a web tool to analyse and predict protein stability changes upon point mutations (single amino acid mutations). This program uses structural environment specific atom potentials and torsion angle potentials to predict ΔΔG, the difference in free energy of unfolding between wild-type and mutant proteins. It requires the protein structure in Protein Data Bank format and the location of the residue to be mutated. The output consists information about mutation site, its structural features (solvent accessibility, secondary structure and torsion angles), and comprehensive information about changes in protein stability for 19 possible substitutions of a specific amino acid mutation. Additionally, it also analyses the ability of the mutated amino acids to adapt the observed torsion angles. Results were tested on 1538 mutations from thermal denaturation and 1603 mutations from chemical denaturation experiments. Several validation tests (split-sample, jack-knife and k-fold) were carried out to ensure the reliability, accuracy and transferability of the prediction method that gives >80% prediction accuracy for most of these validation tests. Thus, the program serves as a valuable tool for the analysis of protein design and stability. The tool is accessible from the link http://cupsat.uni-koeln.de.

INTRODUCTION

Protein design and analysis techniques widely incorporate point mutations with increased or decreased stability. These mutations are carried out experimentally using site-directed mutagenesis and similar techniques. This is time-consuming and often requires the use of computational prediction methods to select the best possible combinations. Random mutations at a specified position may aid in designing thermostable or thermosensitive proteins so that the functionality of a protein can be altered to suit favourable biological and industrial purposes. In industrial processes, protein molecules with higher stability are exposed to non-physiological conditions resulting in stress on their structural and chemical integrity that eventually leads to covalent and non-covalent alteration (1). On the other hand, point mutations are also employed for constructing temperature sensitive mutants (2). Analysis of the stability upon point mutations can also be used to identify a wide spectrum of drug resistance conferring mutations. Experimentally, protein architects often come up with point mutations on multiple sites to design a protein with enhanced stability and invest a lot of resources and time to finalize the process (1). An online software tool can either suggest selective mutations or filter out unwanted combinations. Several groups have already developed tools (3–7) for this purpose with moderate prediction accuracy. CUPSAT (Cologne University Protein Stability Analysis Tool) is a similar tool with slightly better efficiency to analyse and predict stability changes upon point mutations (single amino acid mutations) in proteins.

This tool uses coarse-grained atom potentials and torsion angle potentials to construct the prediction model. The program has been tested on 1538 mutations from thermal denaturation and 1603 mutations from chemical denaturation experiments. Additionally, the model classifies the mutations and mean-force potentials into different structural regions using the solvent accessibility and secondary structure specificity of the mutation site. Several validation tests were carried out that include split sample, jack-knife and k-fold cross validation tests. More than 80% prediction accuracy has been observed. The split-sample and k-fold cross validation tests showed a maximum correlation coefficient of 0.77 with a standard error of <1.0 kcal/mol.

METHODOLOGY

We have developed a novel method for predicting the protein stability changes upon point mutations. Major components that construct the prediction model are the atom potentials and torsion angle potentials. These were derived from a set of 4024 non-redundant protein structures obtained from PISCES web server (8). The atomic level organization of potentials exhibits a wide coverage of local and non-local interactions. For the atom potentials, a radial pair distribution function with an atom classification system has been used. Here, the atoms are classified into 40 different types (9) according to their location, connectivity and chemical nature. Boltzmann's energy values were then calculated from the radial pair distribution of amino acid atoms (10).

Similarly, torsion angle potentials were derived from the distribution of angles φ and ψ for all the amino acids over 4024 protein chains. After calculating Boltzmann' energy values, a Gaussian apodization function (11) has been applied to assign favourable energy values for the neighbouring orientations of observed φ–ψ combinations. This is useful for mutations that adapt slightly altered orientations.

To improve accuracy and specificity of prediction, the mutations and mean-force potentials were classified according to different structural regions. Initially, the secondary structure specificity of mutations and mean-force potentials was implemented and the amino acids were classified into helices, sheets and others. Later, the amino acids belonging to each of these secondary structure elements were further subdivided according to their solvent accessibility (12). Thus, the prediction model has been constructed.

The criteria to evaluate prediction model quality can be divided into two principal steps: the ability to show high correlation (with minimized standard error) between the predicted and experimental ΔΔG of selected mutations with high accuracy to predict the change in stability, and the ability to satisfy multiple validation tests to prove its reliability, accuracy and transferability. Split-sample validation, jack-knife test and k-fold cross validation tests (3-, 4- and 5-fold) were carried out to prove these features.

RESULTS

The experimental point mutation data were derived from ProTherm database (13) and literature (14–16). Totally, 1538 mutations were derived from thermal denaturation experiments (with known ΔΔG) and 1603 mutations were derived from chemical (denaturants such as urea or guanidine hydrochloride) denaturation experiments (with ΔΔGH2O). Separate prediction models were developed for these experiments.

For the thermal denaturation experiments, the overall correlation (Pearson's correlation coefficient) between the predicted and experimental energy values was observed to be 0.87 for 1538 mutations with 85.3% of the mutations correctly predicted to be either stabilizing or destabilizing. However, the correlation was only 0.55 with 75% accuracy before the classification of mutations according to their solvent accessibility and secondary structure specificity. Same classification has been applied for mutations from chemical denaturation experiments which showed an overall correlation of 0.78 (SE 0.96 kcal/mol) with a prediction accuracy of 84.65% for 1603 mutations.

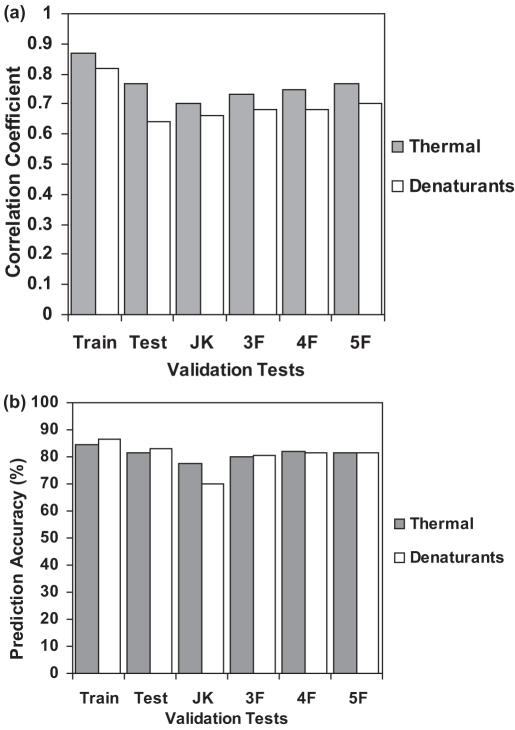

Most of the validation tests showed >80% of the mutations correctly predicted for both thermal and chemical stability values (Figure 1b). For thermal ΔΔG values, the split sample and 5-fold cross validation tests showed a maximum correlation coefficient of 0.77 respectively (Figure 1a). The standard error of these tests remained to be <1 kcal/mol for these tests. For the experimental ΔΔGH2O values, 5-fold cross validation showed a correlation of 0.7 with a standard error of 1.15 kcal/mol. Thus, the algorithm has been tested for its reliability to accurately predict new mutations.

Figure 1.

Correlation coefficient (a) and prediction accuracy (b) between experimental and predicted ΔΔG from thermal (1518 mutations after the removal of 20 outliers) and chemical denaturation experiments (1581 mutations after the removal of 22 outliers). Three validation tests were carried out: Split-sample (Train-Test), Jack-knife (JK) and k-fold (3-, 4-, 5-fold) cross validation tests.

COMPARISON WITH OTHER METHODS

Gilis and Rooman (5) developed statistical potentials to predict the stability changes upon mutations, but the work used only very few mutations due to scarcity of data. Guerois et al. (6) developed a set of empirical energy functions with known interactions and showed a correlation 0.75 between the experimental and predicted energy values for 1088 mutants from chemical denaturation experiments. Capriotti et al. (3,17) developed neural networks and support vector machines (SVMs) with a prediction accuracy of 80%. Cheng et al. (4) also used SVMs and reported an accuracy of 84%. Our previous method (18) based on average assignment showed an accuracy, correlation and standard error, respectively, in the range of 84–89%, 0.64–0.80 and 0.64–1.03 kcal/mol, and this method is applicable only to the pairs of mutants that are available in the training dataset. The present method predicted the stability of protein mutants with an accuracy in the range of 80–87% with a standard error of 0.78–1.15 kcal/mol which is comparable with or better than other methods in the literature. In addition, CUPSAT is relatively faster than many of the currently available algorithms. Usage of neural networks or SVMs may exhibit bottlenecks in program runtime for other cases.

SERVER OPTIONS

The application server mainly includes two modules, accessible from the ‘Run CUPSAT’ menu item: predicting mutant stability from already existing protein (Protein Data Bank, PDB) structures and custom structures. For the latter, the protein structure file must be formatted according to PDB format and uploaded to the CUPSAT server. This module is either needed for the proteins for which the structure has not yet been submitted to PDB, or used for the modelled structures.

Mutant stability from existing PDB structures

This module uses the structures available in the PDB. The details of the mutation site needed for the input are the residue number as well as the actual residue name present at that position. The prediction model has been developed using ΔΔG or ΔΔGH2O values, derived either from thermal or chemical denaturation experiments, respectively. So, an option should additionally be selected by the user to deploy either of these models for predicting mutant stability.

Upon submission, the details of the mutation site are checked with the protein structure, accessing the PDB structure file. In some cases, the specified PDB structure may either contain only one chain identifier or have no identifier explicitly present in the structure. Respectively, the algorithm assumes that the specified residue ID belongs to the single chain present in the structure. On the other hand, multiple chains may be present in a protein structure with only one chain having the specified residue at the specified position. In this case, the algorithm assumes that the given mutation site corresponds to that chain. For all other cases, chain ID must be selected from the drop down menu populated in the next screen.

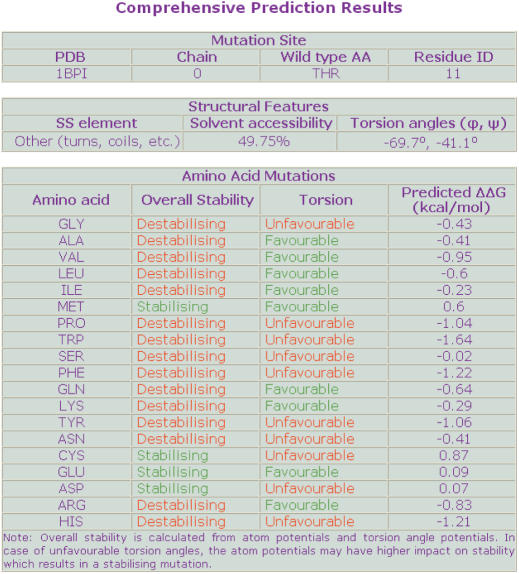

Once the details of mutation site have been submitted to the server, the server shows the structural details (solvent accessibility, secondary structure specificity and main torsion angles) of the mutation site. These details were derived from the DSSP (19) output generated for those PDB files. Upon clicking ‘Proceed’, the next screen shows comprehensive stability information for 19 possible substitutions (Figure 2). These include the overall stability change calculated using the atom and torsion angle potentials together, the adaptation (favourable or unfavourable) of the observed torsion angle combination and the predicted ΔΔG. The negative and positive predicted ΔΔG values mean the destabilizing and stabilizing effect, respectively. Context specific reporting is available for the PDB IDs that are either missing in the local repository or erroneous.

Figure 2.

The prediction results that show comprehensive information about mutation site, secondary structural features and the information about stability change.

Mutant stability from custom protein structures

When a protein structure is not available in the PDB, this module can be used to upload a protein structure in PDB format (20). The atom coordinates of the uploaded structure must be formatted according to PDB file formats guide (version 2.2). Once the upload is complete, the details, such as file size and name of the uploaded structure are briefly shown. Upon confirmation, the rest of process continues as specified in the previous module (Figure 2).

The CUPSAT accesses the local PDB repository that is updated once a month. Basic documentation has been given in the help menu. The energy plots for the torsion angle potential have also been included with ‘Torsion angles’ menu item. It includes the plots of Boltzmann's energy values for 360*360 combinations of φ and ψ. Limited support is also available for the users through the feedback form.

Acknowledgments

The development of CUPSAT web server is supported by the IMPRS (International Max Planck Research School) and the CUBIC project funded by the BMBF (Federal Ministry of Education and Research), Germany. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was also provided by these projects.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shirley B.A. Protein Stability and Folding: Theory and Practice. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lorincz A.T., Reed S.I. Sequence analysis of temperature-sensitive mutations in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene CDC28. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1986;6:4099–4103. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.11.4099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Capriotti E., Fariselli P., Casadio R. I-Mutant2.0: predicting stability changes upon mutation from the protein sequence or structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W306–W310. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng J., Randall A., Baldi P. Prediction of protein stability changes for single-site mutations using support vector machines. Proteins. 2005;62:1125–1132. doi: 10.1002/prot.20810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilis D., Rooman M. PoPMuSiC, an algorithm for predicting protein mutant stability changes: application to prion proteins. Protein Eng. 2000;13:849–856. doi: 10.1093/protein/13.12.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guerois R., Nielsen J.E., Serrano L. Predicting changes in the stability of proteins and protein complexes: a study of more than 1000 mutations. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;320:369–387. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00442-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou H., Zhou Y. Distance-scaled, finite ideal-gas reference state improves structure-derived potentials of mean force for structure selection and stability prediction. Protein Sci. 2002;11:2714–2726. doi: 10.1110/ps.0217002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang G., Dunbrack R.L., Jr PISCES: a protein sequence culling server. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1589–1591. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melo F., Feytmans E. Novel knowledge-based mean force potential at atomic level. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;267:207–222. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sippl M.J. Calculation of conformational ensembles from potentials of mean force. An approach to the knowledge-based prediction of local structures in globular proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;213:859–883. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(05)80269-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niefind K., Schomburg D. Amino acid similarity coefficients for protein modeling and sequence alignment derived from main-chain folding angles. J. Mol. Biol. 1991;219:481–497. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90188-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gromiha M.M., Oobatake M., Kono H., Uedaira H., Sarai A. Role of structural and sequence information in the prediction of protein stability changes: comparison between buried and partially buried mutations. Protein Eng. 1999;12:549–555. doi: 10.1093/protein/12.7.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gromiha M.M., An J., Kono H., Oobatake M., Uedaira H., Sarai A. ProTherm: Thermodynamic Database for proteins and mutants. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:286–288. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Topham C.M., Srinivasan N., Blundell T.L. Prediction of the stability of protein mutants based on structural environment-dependent amino acid substitution and propensity tables. Protein Eng. 1997;10:7–21. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu J., Baase W.A., Baldwin E., Matthews B.W. The response of T4 lysozyme to large-to-small substitutions within the core and its relation to the hydrophobic effect. Protein Sci. 1998;7:158–177. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yutani K., Ogasahara K., Tsujita T., Sugino Y. Dependence of conformational stability on hydrophobicity of the amino acid residue in a series of variant proteins substituted at a unique position of tryptophan synthase alpha subunit. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1987;84:4441–4444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.13.4441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Capriotti E., Fariselli P., Casadio R. A neural-network-based method for predicting protein stability changes upon single point mutations. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:I63–I68. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saraboji K., Gromiha M.M., Ponnuswamy M.N. Average assignment method for predicting the stability of protein mutants. Biopolymers. 2006;82:80–92. doi: 10.1002/bip.20462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kabsch W., Sander C. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers. 1983;22:2577–2637. doi: 10.1002/bip.360221211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berman H.M., Westbrook J., Feng Z., Gilliland G., Bhat T.N., Weissig H., Shindyalov I.N., Bourne P.E. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]