Abstract

The large number of experimentally determined protein 3D structures is a rich resource for studying protein function and evolution, and protein structure comparison (PSC) is a key method for such studies. When comparing two protein structures, almost all currently available PSC servers report a single and sequential (i.e. topological) alignment, whereas the existence of good alternative alignments, including those involving permutations (i.e. non-sequential or non-topological alignments), is well known. We have recently developed a novel PSC method that can detect alternative alignments of statistical significance (alignment similarity P-value <10−5), including structural permutations at all levels of complexity. OPAAS, the server of this PSC method freely accessible at our website (http://opaas.ibms.sinica.edu.tw), provides an easy-to-read hierarchical layout of output to display detailed information on all of the significant alternative alignments detected. Because these alternative alignments can offer a more complete picture on the structural, evolutionary and functional relationship between two proteins, OPAAS can be used in structural bioinformatics research to gain additional insight that is not readily provided by existing PSC servers.

INTRODUCTION

Protein structure comparison (PSC) has been a staple method for obtaining information about a protein when its 3D structure is determined experimentally or predicted computationally. It is therefore not surprising that the development of new PSC algorithms has been continuing for more than two decades with no sign of ceasing (1–6). These efforts are needed not only to meet new scientific challenges but also to benefit maximally from the large number of new structures now pouring in from structural genomics projects (7,8). To these ends, a number of laboratories have created PSC servers in recent years to provide information beyond the basic PSC operations, including, e.g. those that do flexible alignment (9,10), those that discover recurring substructures or motifs (11,12), those that perform multiple structure alignment (13) and those that focus on fast structure feature extraction (14–16).

Here we offer a new PSC server with the functionality to report statistically significant alternative alignments (17,18) and structural permutations (19,20) at all levels of complexity. Our method, named OPAAS, which has been detailed elsewhere (21,22), deduces the probabilities of aligning every possible pair of secondary structure elements (SSEs) between two protein structures prior to the search for a solution of their alignment. This deduction allows the ready identification of most, though not all, statistically significant alignment solutions, many of which being distinct alternatives to the ‘optimal’ solution, the target of conventional PSC operations. As we reported previously from a study of all-against-all database comparisons (22), about half of the alternative alignments were detectable only when permutation, i.e. non-topological alignment, was allowed. Moreover, many of the permuted alignments exhibited a permutation complexity higher than that of circular permutation, meaning that more than two separable regions of the protein structure could be aligned non-sequentially. To quantitatively measure the level of permutation complexity for all the alignments, we devised a permutation index (PI) as follows:

where Si is the size (number of aligned amino acid residues) of the aligned region i and n is the total number of aligned regions. A region is an independently, and, within the region itself, topologically aligned part of an alignment. That is, within a region, all the aligned residues are ordered sequentially, which may or may not be interrupted by gaps, but these regions, if there are more than one, are aligned non-sequentially. It follows that an alignment without any permutation will have just one region, and will have, by definition, a PI value of 1.0. Also by definition, a circular permutation, which involves swapping two regions in a non-topological alignment (19,20), will receive a PI value >1.0 but not >2.0. PI hence furthermore let us know how much the sizes of the separately aligned regions differ. For example, given two permuted protein pairs having PI 3.0 and 2.5, respectively, we will know that they both have three aligned regions, but the sizes of the three regions are equal for the former and vary significantly for the latter.

Both permuted and non-permuted alternative alignments are reported by the OPAAS server in a fashion that is easy for a non-specialist user to grasp the main significance of the comparison as one would with the ‘optimal’ alignment featured by other PSC servers. This is aided by the server's user-friendly interfaces described below, which use intuitive viewing directions, informative tables that can be sorted by different parameters, cascading information windows, and a structured user guide with examples.

OPAAS WEB SERVER LAYOUT

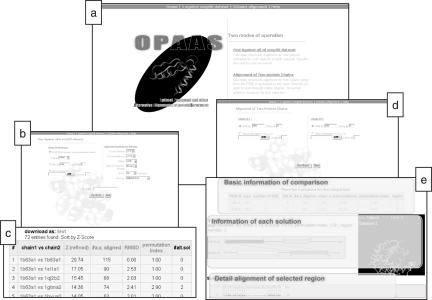

At the portal of the OPAAS web server (Figure 1a) lay two main structure comparison functions, ‘1 against SCOP90 dataset’ and ‘2 chains alignment’, and a Help webpage for a structured OPAAS user guide, which can be viewed on-line (http://opaas.ibms.sinica.edu.tw/help/opaas.html) as well as interactively in different contexts (see below).

Figure 1.

Snapshots of the OPAAS web server. (a) The portal page of the server. Two main applications can be chosen here. (b) The input page for the function of one-against-all search in the SCOP90 dataset. Three different input preferences and optional parameter settings are allowed in the left and right panel, respectively. (c) This table of matched results is retrieved from a database containing pre-computed all-against-all comparison results, which is available only with the one-against-all function. (d) The input page for the function of two chain alignment. (e) Output of a two chain alignment. The information of all alignment solutions (‘optimal’ and alternatives) is hierarchically laid out in three frames.

One-against-all search on SCOP90

The one-against-all on SCOP90 function is designed to find structural neighbors of a protein of interest in the structure classification of proteins (SCOP) (23) database. One of the following three input options (left panel in Figure 1b and user guide 3.1.1) is available for the search: a structure domain already in SCOP90 (SCOP version 1.55, <90% sequence identity non-redundant set), a structure in the current Protein Data Bank (PDB; the server updates its local PDB weekly) (24) with a specified chain (PDB ID option), or a structure in PDB format uploaded by user (User's structure option). All of the three inputs can be accompanied with optional parameter settings for customized output. The parameters that could be changed from default include minimum rough Z-score [for the alignment prior to refinement (21)], minimum refined Z-score, maximum root mean square deviation (RMSD) of Cα superposition between two aligned protein chains, minimum aligned sequence identity, maximum number of shown matches, and sorting options (right panel in Figure 1b and user guide 3.1.2). Unlike the first input option, for which pre-computed results will be retrieved, the last two input options require entry of user's e-mail address (user guide 3.1.3) because the OPAAS server needs time for computation and will return the result via e-mail in, typically, minutes to hours, depending mainly on the stringency of the selected parameters.

For the first input option, a table of matched results retrieved from a pre-computed database will be displayed directly on the web page (Figure 1c and user guide 3.2). In this table, Z-score, #a.a. aligned (number of aligned amino acids), and RMSD reported are those for the optimal alignment solution only, #alt. sol. is the number of alternative alignment solutions that satisfy the parameters specified by the user, and PI indicates the level of permutation complexity as described above. User can sort the table by the field selected (user guide 3.2.2) and download this table either as a plain text file or a comma separated values format file (user guide 3.2.3). User also can click on the matched entry to view details of each alignment solution, which will have exactly the same output as that from using the function of ‘2 chains alignment’ (user guide 3.2.4; see below). For the output of the last two input options, an e-mail of search result with the subject title ‘OPAAS result’ will be sent back to the e-mail address supplied (user guide 3.3). The e-mail contains a table of search result like that of the first input option described above, but to interactively view details of individual alignment solution, the second function, described below, needs to be separately invoked.

Alignment of two protein chains

For the function of ‘2 chains alignment’ (Figure 1d and user guide 4.1), the structures of the two protein chains could either be selected from PDB (i.e. entering PDB ID) or uploaded by user in PDB format. Display of the comparison results, which can be expected to follow immediately upon submission of the request, is split into three frames to show ‘basic information of the comparison’, ‘information of each solution’, and ‘detail alignment of selected region’ (Figure 1e and user guide 4.2).

In the frame of ‘basic information of the comparison’, one of two tables gives some basic information about the two chains compared: size (number of amino acid residues), and number of SSE (user guide 4.2.1). User can click a hyperlink on the name of the two chains placed above the table to learn more about the compared proteins from the PDB website (user guide 4.2.2). The other table shows information of all the solutions (both the ‘optimal’ and alternative alignments, if any) of this comparison including #a.a. aligned (number of aligned residues), RMSD, refined Z-score, PI and region (number of permutedly aligned regions). Clicking on the solution number shows details of that solution in another two frames (user guide 4.2.3). The frame of ‘information of each solution’ shows the alignment of the selected solution graphically (user guide 4.2.4), both in a schematic representation and in a 3D superposition supported by chime plug-in (user guide 4.2.5). A file containing Cartesian coordinates of this alignment solution in standard PDB format can be exported. Different colors of the boxes in the diagram of the schematic representation, as well as of the traces in the 3D superposition, refer to different aligned regions. Clicking on the region box will show ‘detail alignment of the selected region’ in the third frame. The sequence alignment of this region can also be downloaded in MFA (Multi-FASTA Alignment) format by clicking ‘export alignment’ at the top of this frame.

DISCUSSION

The best way to compare two protein structures often depends on the question being asked (6), so having a server like OPAAS that can simultaneously analyze solutions beyond the ‘optimal’ alignment is useful. Although most of the published PSC algorithms can be modified to offer similar capability, to our knowledge, only two PSC servers give user the option to see alternative alignments: Prosup (25) and SARF2 (26), but Prosup is limited to topological alignments and neither offers one-against-all database searching service. Moreover, with an intuitive hierarchical layout of the comparison results and optional parameter settings to view most significant alignments (e.g. with similarity P-value set at 10−5, a typical comparison usually resulted in <5 such solutions), an informative summary that could lead to unexpected insight from unexpected alternative alignments is effectively produced. The main limitation of OPAAS, at its current version, arose from a compromise to trade for computational efficiency, which dictates that a structure must possess at least three SSEs to be compared (21,22); elimination of this limitation is in progress. Significantly, our server allows database search with an efficiency comparable that of the popular CE server (27), despite ours being run on a personal computer (Pentium IV) and being asked to find alternative alignments. The source code of OPAAS is also available at the server for free download for standalone computations and for incorporation of structure database other than SCOP.

Acknowledgments

Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by the Academia Sinica and National Science Council of Taiwan.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Orengo C. Classification of protein folds. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1994;4:429–440. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown N.P., Orengo C.A., Taylor W.R. A protein structure comparison methodology. Comput. Chem. 1996;20:359–380. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gibrat J.-F., Madej T., Bryant S.H. Surprising similarities in structure comparison. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1996;6:377–385. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(96)80058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holm L., Sander C. Mapping the protein universe. Science. 1996;273:595–602. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5275.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koehl P. Protein structure similarities. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2001;11:348–353. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00214-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sierk M.L., Kleywegt G.J. Deja vu all over again: finding and analyzing protein structure similarities. Structure. 2004;12:2103–2111. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Todd A.E., Marsden R.L., Thornton J.M., Orengo C.A. Progress of structural genomics initiatives: an analysis of solved target structures. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;348:1235–1260. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandonia J.M., Brenner S.E. The impact of structural genomics: expectations and outcomes. Science. 2006;311:347–351. doi: 10.1126/science.1121018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shatsky M., Nussinov R., Wolfson H.J. Flexible protein alignment and hinge detection. Proteins. 2002;48:242–256. doi: 10.1002/prot.10100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ye Y., Godzik A. FATCAT: a web server for flexible structure comparison and structure similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W582–W585. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang D.T., Chen C.Y., Chung W.C., Oyang Y.J., Juan H.F., Huang H.C. ProteMiner-SSM: a web server for efficient analysis of similar protein tertiary substructures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W76–W82. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shapiro J., Brutlag D. FoldMiner and LOCK 2: protein structure comparison and motif discovery on the web. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W536–W541. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guda C., Lu S., Scheeff E.D., Bourne P.E., Shindyalov I.N. CE-MC: a multiple protein structure alignment server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W100–W103. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shyu C.R., Chi P.H., Scott G., Xu D. ProteinDBS: a real-time retrieval system for protein structure comparison. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W572–W575. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maiti R., Van Domselaar G.H., Zhang H., Wishart D.S. SuperPose: a simple server for sophisticated structural superposition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W590–W594. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vlahovicek K., Pintar A., Parthasarathi L., Carugo O., Pongor S. CX, DPX and PRIDE: WWW servers for the analysis and comparison of protein 3D structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W252–W254. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng Z.K., Sippl M.J. Optimum superimposition of protein structures: ambiguities and implications. Fold Des. 1996;1:123–132. doi: 10.1016/s1359-0278(96)00021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Godzik A. The structural alignment between two proteins: is there a unique answer? Protein Sci. 1996;5:1325–1338. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560050711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cunningham B.A., Hemperly J.J., Hopp T.P., Edelman G.M. Favin versus concanavalin A: circularly permuted amino acid sequences. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 1979;76:3218–3222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.7.3218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heinemann U., Hahn M. Circular permutation of polypeptide chains: implications for protein folding and stability. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 1995;64:121–143. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(95)00013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shih E.S.C., Hwang M.J. Protein structure comparison by probability-based matching of secondary structure elements. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:735–741. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shih E.SC., Hwang M.J. Alternative alignments from comparison of protein structures. Proteins. 2004;56:519–527. doi: 10.1002/prot.20124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murzin A.G., Brenner S.E., Hubbard T., Chothia C. SCOP: a structural classification of proteins database for the investigation of sequences and structures. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;247:536–540. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berman H.M., Westbrook J., Feng Z., Gilliland G., Bhat T.N., Weissig H., Shindyalov I.N., Bourne P.E. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lackner P., Koppensteiner W.A., Sippl M.J., Domingues F.S. ProSup: a refined tool for protein structure alignment. Protein Eng. 2000;13:745–752. doi: 10.1093/protein/13.11.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alexandrov N.N., Fischer D. Analysis of topological and nontopological structural similarities in the PDB: new examples with old structures. Proteins. 1996;25:354–365. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0134(199607)25:3<354::AID-PROT7>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shindyalov I.N., Bourne P.E. Protein structure alignment by incremental combinatorial extension (CE) of the optimal path. Protein Eng. 1998;11:739–747. doi: 10.1093/protein/11.9.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]