Claude Shannon founded information theory in the 1940s. The theory has long been known to be closely related to thermodynamics and physics through the similarity of Shannon's uncertainty measure to the entropy function. Recent work using information theory to understand molecular biology has unearthed a curious fact: Shannon's channel capacity theorem only applies to living organisms and their products, such as communications channels and molecular machines that make choices from several possibilities. Information theory is therefore a theory about biology, and Shannon was a biologist.

Shannon (30 April 1916-24 February 2001) is heralded for his major contributions to the fundamentals of computers and communications systems [1]-[4]. His Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) master's thesis is famous because in it he showed that digital circuits can be expressed by Boolean logic. Thus, one can transform a circuit diagram into an equation, rearrange the equation algebraically, and then draw a new circuit diagram that has the same function. By this means, one can, for example, reduce the number of transistors needed to accomplish a particular function.

Shannon's work at Bell Labs in the 1940s led to the publication of the famous paper “A Mathematical Theory of Communication” in 1948 [5] and to the lesser known but equally important “Communication in the Presence of Noise” in 1949 [6]. In these groundbreaking papers, Shannon established information theory. It applies not only to human and animal communications, but also to the states and patterns of molecules in biological systems [7]-[9]. At the time, Bell Labs was the research and development part of the American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T), which was in the business of selling the ability to communicate information. How can information be defined precisely? Shannon, a mathematician, set down several criteria for a useful, rigorous definition of information, and then he showed that only one formula satisfied these criteria. The definition, which has withstood the test of more than 50 years, precisely answered the question What is AT&T selling? The answer was information transmission in bits per second. Of course, this immediately raised another question: How much information can we send over existing equipment, our phone lines? To answer this, Shannon developed a mathematical theory of the channel capacity. Before delving into how he arrived at this concept, which explains why Shannon was a biologist, it is necessary to understand the surprising (Shannon's word) channel capacity theorem, and how it was developed.

The channel capacity C in bits per second, depends on only three factors: the power P of the signal at the receiver, the noise N disturbing the signal at the receiver, and the bandwidth W, which is the span of frequencies used in the communication:

| 1 |

Suppose one wishes to transmit some information at a rate R, also in bits per second (b/s). First, Shannon showed that when the rate exceeds the capacity (R > C), the communication will fail and at most C b/s will get through. A rough analogy is putting water through a pipe. There is an upper limit for how fast water can flow; at some point, the resistance in the pipe will prevent further increases or the pipe will burst.

The surprise comes when the rate is less than or equal to the capacity (R ≤ C). Shannon discovered, and proved mathematically, that in this case one may transmit the information with as few errors as desired! Error is the number of wrong symbols received per second. The probability of errors can be made small but cannot be eliminated. Shannon pointed out that the way to reduce errors is to encode the messages at the transmitter to protect them against noise and then to decode them at the receiver to remove the noise. The clarity of modern telecommunications, CDs, MP3s, DVDs, wireless, cellular phones, etc., came about because engineers have learned how to make electrical circuits and computer programs that do this coding and decoding. Because they approach the Shannon limits, the recently developed Turbo codes promise to revolutionize communications again by providing more data transmission over the same channels [10], [11].

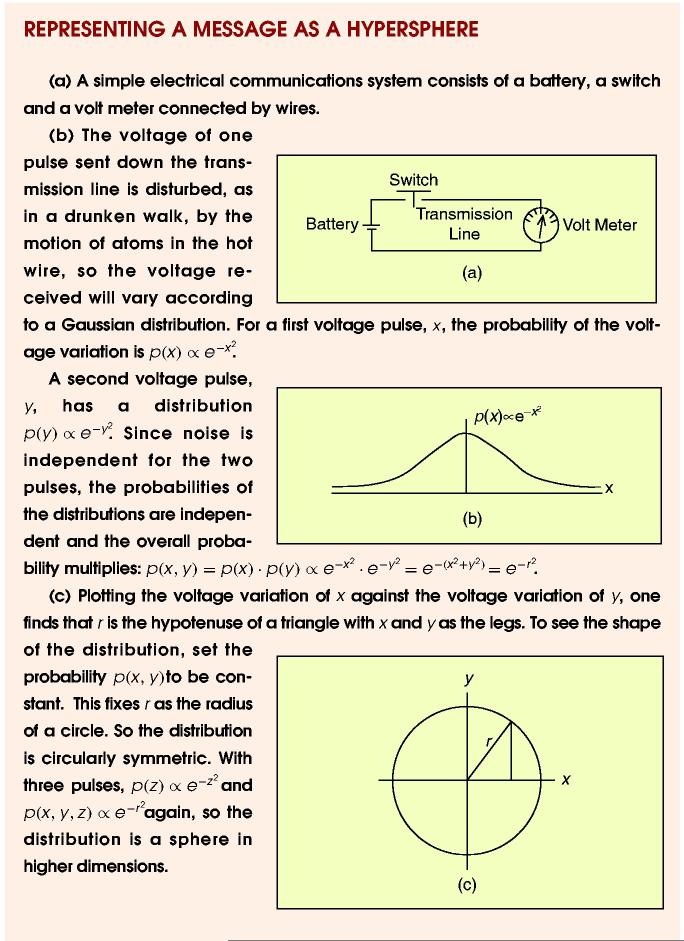

What made all this possible? It is a key idea buried in a beautiful geometrical derivation of the channel capacity in Shannon's 1949 paper [6]. Suppose that you and I decide to set up a simple communications system (Figure 1). On my end, I have a 1-volt (V) battery and a switch. We run two wires over to you and install a volt meter on your end. When I close the switch, you see the meter jump from 0 to 1 V. If I set the switch every second, you receive up to 1 b/s. But on closer inspection, you notice that the meter doesn't always read exactly 1 V. Sometimes it reads 0.98, other times 1.05, and so on. The distribution of values is bell shaped (Gaussian), because the wire is hot (300 K). From a thermodynamic viewpoint, the heat is atomic motions, and they disturb the signal, making it noisy. You can hear this as the static hiss on a radio or see it as snow on a television screen.

Fig. 1.

Representing a message as a hypersphere.

Shannon realized that the noise added to one digital pulse would generally make the overall amplitude different from that of another, otherwise identical, pulse. Further, the noise amplitudes for two pulses are independent. When two quantities are independent, one can represent this geometrically by graphing them at 90° to each other (orthogonal). Shannon recognized that for two pulses, the individual Gaussians combined to make a little circular smudge on a two dimensional graph of the voltage of the first pulse plotted against the voltage of the second pulse, as shown in Figure 1. If three digital pulses are sent, the possible combinations can be plotted as corners of a cube in three dimensions. The receiver, however, does not see the pristine corners of the cube. Instead, surrounding each corner are fuzzy spheres that represent the probabilities of how much the signal can be distorted.

With four pulses, the graph must be made in four-dimensional space, and the cube becomes a hypercube (tesseract), but the spheres are still there at each corner.

Shannon realized that when one looks at many pulses—a message—they correspond to a single point in a high dimensional space.

Essentially, we have replaced a complex entity (say, a television signal) in a simple environment (the signal requires only a plane for its representation as f(t)) by a simple entity (a point) in a complex environment (2TW dimensional space) [6].

(In the preceding, T is the message time and W is the bandwidth.) The transmitter picks the point and the receiver receives a point located in a fuzzy sphere around the transmitted point. This would not be remarkable except for an interesting property of high-dimensional spheres. As the dimension goes up, almost all the received points of the sphere condense onto the surface at radius r, as shown by Brillouin and Callen [7], [12], [13]. At high dimension, the sphere density function becomes a sharply pointed distribution [7]. Shannon called these spheres “sharply defined billiard balls,” but I prefer “ping-pong balls” because they are hollow and have thin shells.

The sharp definition of the sphere surface at high dimension has a dramatic consequence. Suppose that I want to send you two messages. I represent these as two points in a high-dimensional space. During transmission, the signal encounters thermal noise and is degraded in all possible ways so that you receive results somewhere in two spheres. If the spheres are far enough apart, you can easily determine the nearest sphere center because we agree beforehand where I will place my points. That is, you can decode the noisy signal and remove the noise! Of course, this only works if the spheres do not overlap. If the spheres overlap, then sometimes you cannot determine which message I sent.

The total power of the received signal allows me (at the transmitter) to pick only a limited number of messages, and they all must be within some distance from the origin of the high-dimensional space. That is, there is a larger sphere around all the smaller thermal spheres that represent possible received messages. Shannon recognized this, and then he computed how many little message spheres could fit into the big sphere provided by the power and also the thermal noise, which extends the big sphere radius. By dividing the volume of the big sphere by the volume of a little one, he determined the maximum number of messages just as one can estimate the number of gumballs in a gumball machine (Figure 2). Taking the logarithm (base 2) gave the result in bits. This gave him the channel capacity formula (1), and, using the geometry of the situation, he proved the channel capacity theorem [6].

Fig. 2.

A gumball machine represents a communications system, as seen by a receiver. Each gumball represents the volume of coding space a single transmitted message (a point in the space) could be moved to after thermal noise has distorted the message during communication. The entire space accessible to the receiver, represented by the outer glass shell, is determined by the power received, the thermal noise, and the bandwidth. The number of gumballs determines the capacity of the machine and is estimated by dividing the volume enclosed by the outer glass shell by the volume of each gumball. A similar computation gives the channel capacity of a communications system [6]. The painting is by Wayne Thiebaud (b. 1920) Three Machines (1963), oil on canvas, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; copyright Wayne Thiebaud/licensed by VAGA, New York, N.Y., reproduced with permission. The image was obtained from http://www.artnet.com/magazine/news/newthismonth/walrobinson2-1-16.asp.

We can see now that this theorem relies on two important facts. First, by using long messages, one gets high dimensions and so the spheres have sharply defined surfaces. This allows for as few errors in communication as one desires. Second, if one packs the spheres together in a smart way, one can send more data, all the way up to the channel capacity. The sphere packing arrangement is called the coding, and for more than 50 years, mathematicians have been figuring out good ways to pack spheres in high dimensions. This results in the low error rates of modern communications systems.

Even when they are far apart, the spheres always intersect by some amount because Gaussian distributions have infinite tails. That is why one can't avoid error entirely. On the other hand, if the distance between two sphere centers is too small, then the two spheres intersect strongly. When random thermal noise places the received point into the intersection region, the two corresponding messages will be confused by the receiver. The consequences of this could be disastrous for the sender or the recipient, who could even die from a misunderstanding.

Because a communications failure can have serious consequences for a living organism, Darwinian selection will prevent significant sphere overlap. It can also go to work to sharpen the spheres and to pack them together optimally. For example, a metallic key in a lock is a multidimensional device because the lock has many independent pins that allow a degree of security. When one duplicates the key, it is often reproduced incorrectly, and one will have to reject the bad one (select against it). If one's home is broken into because the lock was picked, one might replace the lock with a better one that is harder to pick (has higher dimension). Indeed, key dimension has increased over time. The ancient Romans and the monks of the Middle Ages used to carry simple keys for wooden door locks with one or two pins, while the key to my lab seems to have about 12 dimensions.

All communications systems have the property that they are important to living organisms. That is, too much sphere overlap is detrimental. In contrast, although the continuously changing microstates of a physical system, such as a rock on the moon or a solar prominence, can be represented by one or more thermal noise spheres, these spheres may overlap, and there is no consequence because there is no reproduction and there are no future generations. A living organism with a nonfunctional communication system is unlikely to have progeny, so its genome may disappear.

Shannon's crucial concept was that the spheres must not intersect in a communications system, and from this he built the channel capacity formula and theorem. But, at its root, the concept that the spheres must be separated is a biological criterion that does not apply to physical systems in general. Although it is well known that Shannon's uncertainty measure is similar to the entropy function, the channel capacity and its theorem are rarely, if ever, mentioned in thermodynamics or physics, perhaps because these aspects of information theory are about biology, so no direct application could be found in those fields. Since he used a property of biology to formulate his mathematics, I conclude that Claude Shannon was doing biology and was therefore, effectively, a biologist—although he was probably unaware of it.

It is not surprising that Shannon's mathematics can be fruitfully applied to understanding biological systems [7], [8], [14]. Models built with information theory methods can be used to characterize the patterns in DNA or RNA to which proteins and other molecules bind [15]-[19] and even can be used to predict if a change to the DNA will cause a genetic disease in humans [20], [21]. Further information about molecular information theory is available at the Web site http://www.ccrnp.ncifcrf.gov/~toms/.

What are the implications of the idea that Shannon was doing biology? First, it means that communications systems and molecular biology are headed on a collision course. As electrical circuits approach molecular sizes, the results of molecular biologists can be used to guide designs [22], [23]. We might envision a day when communications and biology are treated as a single field. Second, codes discovered for communications potentially teach us new biology if we find the same codes in a biological system. Finally, the reverse is also to be anticipated: discoveries in molecular biology about systems that have been refined by evolution for billions of years should tell us how to build new and more efficient communications systems.

Acknowledgments

I thank Denise Rubens, Herb Schneider, Doris Schneider, John Spouge, John Garavelli, Pete Rogan, Jim Ellis, Ilya Lyakhov, Michael Levashov, Zehua Chen, Danielle Needle, and Marirose Coulson for comments on the manuscript. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Cancer Institute—Fredrick.

Biography

Thomas D. Schneider is a research biologist at the National Cancer Institute in Frederick, Maryland. He graduated from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in biology (1978) and received his Ph.D. from the University of Colorado in molecular biology (1986). His primary work is analyzing the binding sites of proteins on DNA and RNA in bits of information. Since beginning this research, he thought that he was taking Shannon's ideas “kicking and screaming” into molecular biology. But, after crawling out of many pitfalls, the connection between information theory and molecular biology became so clear and the results so plentiful that he dug deeper and eventually discovered that information theory was already about biology.

References

- [1].Sloane NJA, Wyner AD. Claude Elwood Shannon: Collected Papers. IEEE Press; Piscataway, NJ: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Pierce JR. An Introduction to Information Theory: Symbols, Signals and Noise. 2nd ed. Dover Publications, Inc.; New York: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Calderbank R, Sloane NJ. “Obituary: Claude Shannon (1916-2001),”. Nature. 2001;410:768. doi: 10.1038/35071223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Golomb SW. “Claude E. Shannon (1916-2001),”. Sci. 2001;292:455. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Shannon CE. “A mathematical theory of communication,”. http://cm.bell-labs.com/cm/ms/what/shannonday/paper.html Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948;27:379, 623–423. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Shannon CE. “Communication in the presence of noise,”. Proc. IRE. 1949;37:10–21. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Schneider TD. “Theory of molecular machines. I. Channel capacity of molecular machines,”. http://www.ccrnp.ncifcrf.gov/~toms/paper/ccmm/ J. Theor. Biol. 1991;148:83–123. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(05)80466-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Schneider TD. “Theory of molecular machines. II. Energy dissipation from molecular machines,”. http://www.ccrnp.ncifcrf.gov/~toms/paper/edmm/ J. Theor. Biol. 1991;148:125–137. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(05)80467-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Schneider TD. “Sequence logos, machine/channel capacity, Maxwell's demon, and molecular computers: a review of the theory of molecular machines,”. http://www.ccrnp.ncifcrf.gov/~toms/paper/nano2/ Nanotechnol. 1994;5:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Berrou C, Glavieux A, Thitimajshima P. “Near Shannon limit error-correcting coding and decoding: Turbo-codes,”. Proc. IEEE. May 1993;2:1064–1070. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Guizzo E. “Closing in on the perfect code,”. IEEE Spectr. Mar 2004;41(3):36–42. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Brillouin L. In Science and Information Theory. Academic; New York: 1962. p. 247. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Callen HB. In Thermodynamics and an Introduction to Thermostatistics. Wiley; New York: 1985. p. 347. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Schneider TD, Stormo GD, Gold L, Ehrenfeucht A. “Information content of binding sites on nucleotide sequences,”. http://www.ccrnp.ncifcrf.gov/~toms/paper/schneider1986/ J. Mol. Biol. 1986;188:415–431. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Stephens RM, Schneider TD. “Features of spliceosome evolution and function inferred from an analysis of the information at human splice sites,”. http://www.ccrnp.ncifcrf.gov/~toms/paper/splice/ J. Mol. Biol. 1992;228:1124–1136. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90320-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hengen PN, Bartram SL, Stewart LE, Schneider TD. “Information analysis of Fis binding sites,”. http://www.ccrnp.ncifcrf.gov/~toms/paper/fisinfo/ Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(24):4994–5002. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Shultzaberger RK, Schneider TD. “Using sequence logos and information analysis of Lrp DNA binding sites to investigate discrepancies between natural selection and SELEX,”. http://www.ccrnp.ncifcrf.gov/~toms/paper/lrp/ Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27(3):882–887. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.3.882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Shultzaberger RK, Bucheimer RE, Rudd KE, Schneider TD. “Anatomy of Escherichia coli ribosome binding sites,”. http://www.ccrnp.ncifcrf.gov/~toms/paper/flexrbs/ J. Mol. Biol. 2001;313:215–228. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zheng M, Doan B, Schneider TD, Storz G. “OxyR and SoxRS regulation of fur,”. http://www.ccrnp.ncifcrf.gov/~toms/paper/oxyrfur/ J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:4639–4643. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.15.4639-4643.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Rogan PK, Schneider TD. “Using information content and base frequencies to distinguish mutations from genetic polymorphisms in splice junction recognition sites,”. http://www.ccrnp.ncifcrf.gov/~toms/paper/colonsplice/ Human Mutation. 1995;6:74–76. doi: 10.1002/humu.1380060114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rogan PK, Faux BM, Schneider TD. “Information analysis of human splice site mutations,”. Human Mutation. 1998;12:153–171. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1998)12:3<153::AID-HUMU3>3.0.CO;2-I. http://www.ccrnp.ncifcrf.gov/~toms/paper/rfs/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hengen PN, Lyakhov IG, Stewart LE, Schneider TD. “Molecular flip-flops formed by overlapping Fis sites,”. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(22):6663–6673. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Schneider TD, Hengen PN. “Molecular computing elements: Gates and flip-flops,”. U.S. Patent 6 774 222, European Patent 1057118. U.S. Patent WO 99/42929, PCT/US99/03469. 2004 http://www.ccrnp.ncifcrf.gov/~toms/patent/molecularcomputing/