Abstract

Background

Geographic patterns of cancer death rates in the U.S. have customarily been presented by county or aggregated into state economic or health service areas. Herein, we present the geographic patterns of cancer death rates in the U.S. by congressional district. Many congressional districts do not follow state or county boundaries. However, counties are the smallest geographical units for which death rates are available. Thus, a method based on the hierarchical relationship of census geographic units was developed to estimate age-adjusted death rates for congressional districts using data obtained at county level. These rates may be useful in communicating to legislators and policy makers about the cancer burden and potential impact of cancer control in their jurisdictions.

Results

Mortality data were obtained from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) for 1990–2001 for 50 states, the District of Columbia, and all counties. We computed annual average age-adjusted death rates for all cancer sites combined, the four major cancers (lung and bronchus, prostate, female breast, and colorectal cancer) and cervical cancer. Cancer death rates varied widely across congressional districts for all cancer sites combined, for the four major cancers, and for cervical cancer. When examined at the national level, broad patterns of mortality by sex, race and region were generally similar with those previously observed based on county and state economic area.

Conclusion

We developed a method to generate cancer death rates by congressional district using county-level mortality data. Characterizing the cancer burden by congressional district may be useful in promoting cancer control and prevention programs, and persuading legislators to enact new cancer control programs and/or strengthening existing ones. The method can be applied to state legislative districts and other analyses that involve data aggregation from different geographic units.

Background

Cancer death rates presented by geographic boundaries such as state and county, state economic areas, and health service areas have been useful in monitoring temporal trends in allocating public health resources [1,2], and in some instances, in generating etiological hypotheses. These rates are less useful for communicating to legislators and policy makers whose jurisdictions are not defined by state or county boundaries. There have been no published studies that attempted to measure cancer death rates within congressional districts.

Public policy and legislation play a critically important role in efforts to reduce the burden of cancer. For example, the American Cancer Society estimates that in 2006 about 170,000 of the 564,830 cancer deaths are expected to be caused by tobacco use alone [3]. Policy measures that are proven to reduce smoking prevalence include excise taxes and funding for state comprehensive tobacco control programs [4-6]. Declines in smoking prevalence among men as a result of public health efforts have had a major influence on the declines in cancer mortality in the last decade.

We present a method to calculate cancer death rates according to congressional district that may be useful in advocating for legislative initiatives and funding for cancer research and prevention programs.

Results and discussion

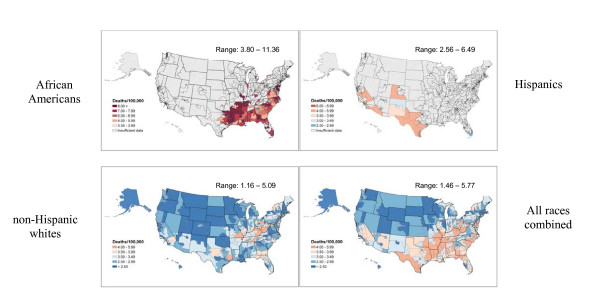

Maps of cancer death rates by congressional district were prepared for men and women, for all races combined, and for African Americans, non-Hispanic whites, and Hispanics (Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, 5); Hispanics are not mutually exclusive of whites and African Americans. Regional patterns of cancer mortality for African Americans and non-Hispanic whites were compared to previously published maps based on counties and state economic areas [1]. Although maps of cancer mortality by congressional district were also prepared for Hispanics, regional patterns are difficult to interpret because of insufficient data to calculate rates for most parts of the country. When examined at the national level, broad patterns of mortality for African Americans and non-Hispanic whites by sex and region were consistent with those previously observed [1]. Geographic variations in cancer death rates may reflect, in part, regional variations in risk factors such as smoking and obesity, early detection and screening, and access to and utilization of medical services.

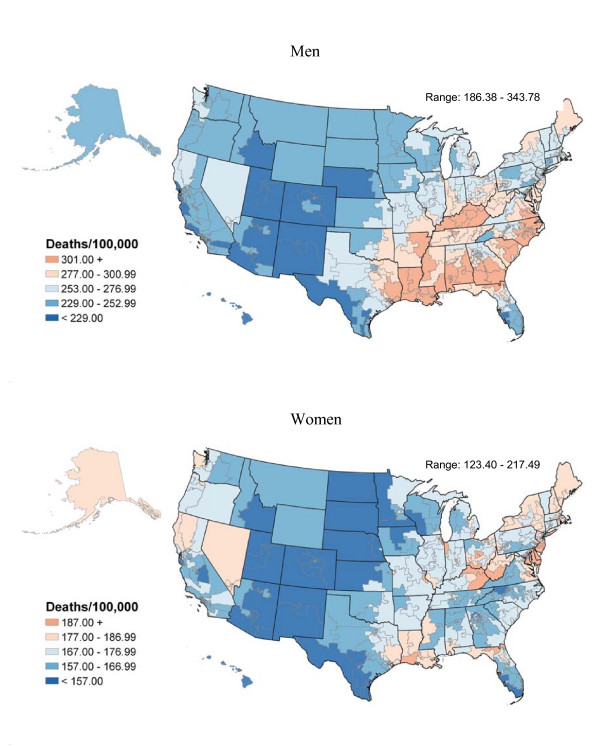

Figure 1.

All cancers combined death rates per 100,000 person-years by congressional district (age-adjusted 2000 US population), 1990–2001.

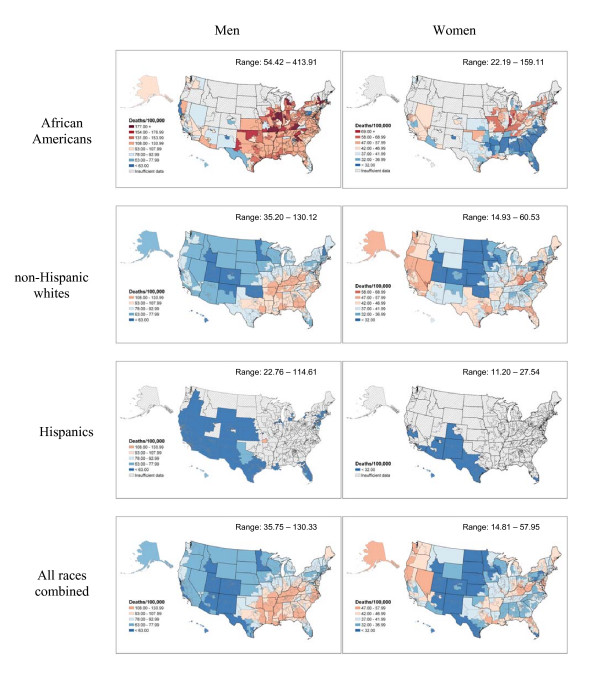

Figure 2.

Lung cancer death rates per 100,000 person-years by congressional district (age-adjusted 2000 US population), 1990–2001.

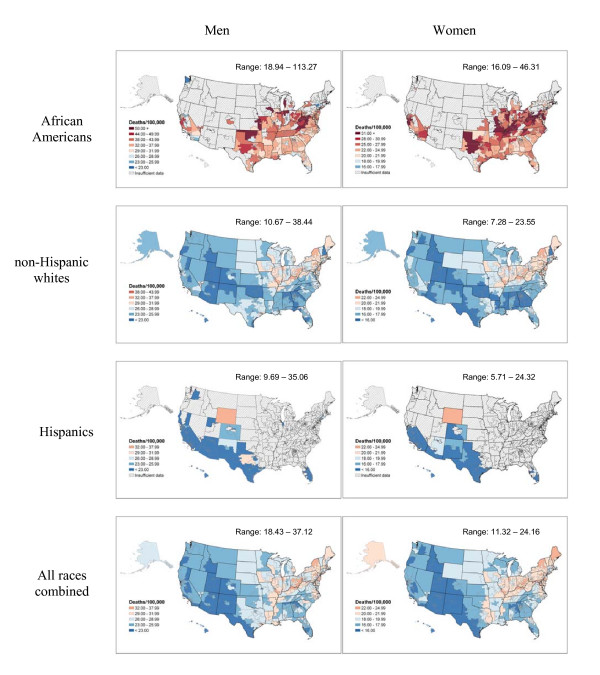

Figure 3.

Colorectal cancer death rates per 100,000 person-years by congressional district (age-adjusted 2000 US population), 1990–2001.

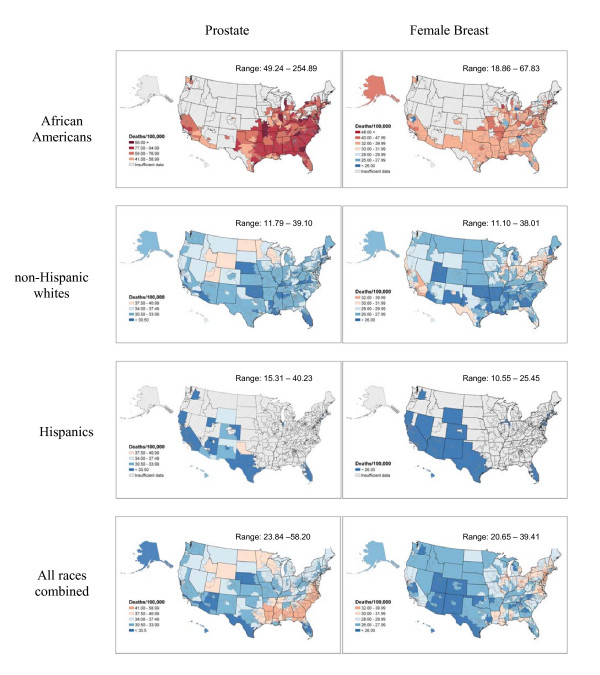

Figure 4.

Prostate, female breast cancer death rates per 100,000 person-years by congressional district (age-adjusted 2000 US population), 1990–2001.

Figure 5.

Cervical cancer death rates per 100,000 person-years by congressional district (age-adjusted 2000 US population), 1990–2001.

Figure 1 shows geographic patterns of death rates for all cancer sites combined by congressional district in the United States. In men, rates range from 186.3 in Utah congressional district #3 to 343.7 in District of Columbia (Table 1) and in women, from 123.4 in Utah congressional district #1 to 217.4 in Pennsylvania congressional district #2 (Table 2). Generally, the patterns for all cancer sites combined are strikingly similar to those for lung cancer (Figure 2), reflecting the importance of lung cancer as a cause of cancer death, and the strong association of lung and cancers of several other sites with tobacco smoking. Lung cancer death rates in all races combined range from 35.7 in Utah congressional district #1 to 130.3 in Kentucky congressional district #5 for men and from 14.8 in Utah congressional district #3 to 57.9 in Kentucky congressional district #5 for women. Lung cancer death rates are the highest in congressional districts in Appalachia and the south among non-Hispanic white men and in the Midwest and the south among African American men. In contrast, among women, rates are the highest in congressional districts in the Midwest among African Americans and in the west, Appalachia, and the coastal south among non-Hispanic whites. Historically, smoking was more common in the south among men and in the west among women, especially among whites [7]. Although patterns of lung cancer mortality in the 1990's primarily reflect smoking patterns in the 1950's and 1960's, the burden of death from all cancers and lung cancer by congressional district can be used to illustrate the importance of tobacco control measures as well as to document local needs for cancer treatment and associated services.

Table 1.

Age-adjusted death rates, all cancers combined, for US men by congressional district (CD), 1990–2001

| State | CD | Rate | State | CD | Rate | State | CD | Rate | State | CD | Rate |

| AL | 0101 | 311.55 | FL | 1223 | 233.18 | MN | 2705 | 246.79 | OR | 4102 | 245.13 |

| AL | 0102 | 309.74 | FL | 1224 | 262.08 | MN | 2706 | 243.38 | OR | 4103 | 270.72 |

| AL | 0103 | 312.74 | FL | 1225 | 231.74 | MN | 2707 | 235.05 | OR | 4104 | 246.92 |

| AL | 0104 | 290.71 | GA | 1301 | 306.92 | MN | 2708 | 250.08 | OR | 4105 | 246.09 |

| AL | 0105 | 262.11 | GA | 1302 | 318.36 | MS | 2801 | 299.09 | PA | 4201 | 341.70 |

| AL | 0106 | 286.12 | GA | 1303 | 310.67 | MS | 2802 | 330.08 | PA | 4202 | 343.25 |

| AL | 0107 | 307.46 | GA | 1304 | 256.56 | MS | 2803 | 299.83 | PA | 4203 | 262.65 |

| AK | 0299 | 248.48 | GA | 1305 | 283.68 | MS | 2804 | 314.84 | PA | 4204 | 279.79 |

| AZ | 0401 | 205.84 | GA | 1306 | 271.97 | MO | 2901 | 282.13 | PA | 4205 | 250.82 |

| AZ | 0402 | 239.41 | GA | 1307 | 253.45 | MO | 2902 | 256.11 | PA | 4206 | 251.69 |

| AZ | 0403 | 229.35 | GA | 1308 | 283.26 | MO | 2903 | 298.52 | PA | 4207 | 276.22 |

| AZ | 0404 | 229.35 | GA | 1309 | 276.76 | MO | 2904 | 264.86 | PA | 4208 | 272.61 |

| AZ | 0405 | 229.35 | GA | 1310 | 276.81 | MO | 2905 | 277.15 | PA | 4209 | 253.47 |

| AZ | 0406 | 227.76 | GA | 1311 | 290.20 | MO | 2906 | 263.57 | PA | 4210 | 260.76 |

| AZ | 0407 | 211.10 | GA | 1312 | 295.19 | MO | 2907 | 272.91 | PA | 4211 | 274.08 |

| AZ | 0408 | 234.26 | GA | 1313 | 267.16 | MO | 2908 | 290.16 | PA | 4212 | 268.01 |

| AR | 0501 | 307.86 | HI | 1501 | 202.59 | MO | 2909 | 264.05 | PA | 4213 | 295.64 |

| AR | 0502 | 292.46 | HI | 1502 | 202.59 | MT | 3099 | 248.52 | PA | 4214 | 288.08 |

| AR | 0503 | 264.97 | ID | 1601 | 234.87 | NE | 3101 | 242.74 | PA | 4215 | 253.36 |

| AR | 0504 | 296.35 | ID | 1602 | 221.35 | NE | 3102 | 267.93 | PA | 4216 | 244.42 |

| CA | 0601 | 257.81 | IL | 1701 | 287.98 | NE | 3103 | 226.06 | PA | 4217 | 266.93 |

| CA | 0602 | 266.90 | IL | 1702 | 287.63 | NV | 3201 | 268.19 | PA | 4218 | 277.63 |

| CA | 0603 | 245.75 | IL | 1703 | 287.98 | NV | 3202 | 254.67 | PA | 4219 | 252.99 |

| CA | 0604 | 236.01 | IL | 1704 | 287.98 | NV | 3203 | 268.19 | RI | 4401 | 276.83 |

| CA | 0605 | 245.61 | IL | 1705 | 287.98 | NH | 3301 | 270.77 | RI | 4402 | 278.12 |

| CA | 0606 | 227.02 | IL | 1706 | 256.03 | NH | 3302 | 266.04 | SC | 4501 | 293.71 |

| CA | 0607 | 244.64 | IL | 1707 | 287.98 | NJ | 3401 | 292.38 | SC | 4502 | 279.65 |

| CA | 0608 | 244.76 | IL | 1708 | 265.27 | NJ | 3402 | 290.30 | SC | 4503 | 283.26 |

| CA | 0609 | 246.04 | IL | 1709 | 287.98 | NJ | 3403 | 277.44 | SC | 4504 | 280.26 |

| CA | 0610 | 242.33 | IL | 1710 | 269.31 | NJ | 3404 | 275.30 | SC | 4505 | 311.21 |

| CA | 0611 | 242.00 | IL | 1711 | 272.33 | NJ | 3405 | 259.29 | SC | 4506 | 313.81 |

| CA | 0612 | 232.65 | IL | 1712 | 296.31 | NJ | 3406 | 273.02 | SD | 4699 | 246.34 |

| CA | 0613 | 246.04 | IL | 1713 | 257.26 | NJ | 3407 | 260.46 | TN | 4701 | 288.63 |

| CA | 0614 | 216.61 | IL | 1714 | 248.91 | NJ | 3408 | 279.73 | TN | 4702 | 281.01 |

| CA | 0615 | 208.66 | IL | 1715 | 267.45 | NJ | 3409 | 260.33 | TN | 4703 | 293.12 |

| CA | 0616 | 208.66 | IL | 1716 | 266.46 | NJ | 3410 | 285.53 | TN | 4704 | 299.25 |

| CA | 0617 | 220.87 | IL | 1717 | 273.62 | NJ | 3411 | 253.50 | TN | 4705 | 301.32 |

| CA | 0618 | 248.61 | IL | 1718 | 274.38 | NJ | 3412 | 271.16 | TN | 4706 | 282.64 |

| CA | 0619 | 239.15 | IL | 1719 | 275.28 | NJ | 3413 | 283.59 | TN | 4707 | 295.64 |

| CA | 0620 | 235.22 | IN | 1801 | 297.56 | NM | 3501 | 224.30 | TN | 4708 | 299.44 |

| CA | 0621 | 231.25 | IN | 1802 | 273.64 | NM | 3502 | 227.97 | TN | 4709 | 323.86 |

| CA | 0622 | 241.10 | IN | 1803 | 264.13 | NM | 3503 | 205.63 | TX | 4801 | 298.28 |

| CA | 0623 | 216.41 | IN | 1804 | 278.64 | NY | 3601 | 272.33 | TX | 4802 | 302.76 |

| CA | 0624 | 218.17 | IN | 1805 | 265.45 | NY | 3602 | 269.70 | TX | 4803 | 251.80 |

| CA | 0625 | 234.12 | IN | 1806 | 271.20 | NY | 3603 | 245.27 | TX | 4804 | 280.20 |

| CA | 0626 | 239.12 | IN | 1807 | 310.26 | NY | 3604 | 236.48 | TX | 4805 | 296.25 |

| CA | 0627 | 229.74 | IN | 1808 | 287.76 | NY | 3605 | 225.59 | TX | 4806 | 281.01 |

| CA | 0628 | 229.74 | IN | 1809 | 286.44 | NY | 3606 | 222.78 | TX | 4807 | 277.95 |

| CA | 0629 | 229.74 | IA | 1901 | 259.56 | NY | 3607 | 247.39 | TX | 4808 | 282.93 |

| CA | 0630 | 229.74 | IA | 1902 | 250.56 | NY | 3608 | 247.21 | TX | 4809 | 302.08 |

| CA | 0631 | 229.74 | IA | 1903 | 256.54 | NY | 3609 | 229.07 | TX | 4810 | 242.29 |

| CA | 0632 | 229.74 | IA | 1904 | 242.92 | NY | 3610 | 242.88 | TX | 4811 | 272.71 |

| CA | 0633 | 229.74 | IA | 1905 | 244.45 | NY | 3611 | 242.94 | TX | 4812 | 272.87 |

| CA | 0634 | 229.74 | KS | 2001 | 236.43 | NY | 3612 | 240.42 | TX | 4813 | 267.39 |

| CA | 0635 | 229.74 | KS | 2002 | 254.68 | NY | 3613 | 263.79 | TX | 4814 | 267.50 |

| CA | 0636 | 229.74 | KS | 2003 | 243.40 | NY | 3614 | 241.66 | TX | 4815 | 200.38 |

| CA | 0637 | 229.74 | KS | 2004 | 259.82 | NY | 3615 | 251.70 | TX | 4816 | 223.16 |

| CA | 0638 | 229.74 | KY | 2101 | 301.17 | NY | 3616 | 267.24 | TX | 4817 | 270.88 |

| CA | 0639 | 229.74 | KY | 2102 | 302.60 | NY | 3617 | 255.21 | TX | 4818 | 277.95 |

| CA | 0640 | 224.83 | KY | 2103 | 319.57 | NY | 3618 | 245.32 | TX | 4819 | 258.34 |

| CA | 0641 | 248.53 | KY | 2104 | 311.74 | NY | 3619 | 263.83 | TX | 4820 | 252.64 |

| CA | 0642 | 232.32 | KY | 2105 | 314.33 | NY | 3620 | 266.28 | TX | 4821 | 247.33 |

| CA | 0643 | 253.34 | KY | 2106 | 306.21 | NY | 3621 | 267.14 | TX | 4822 | 263.97 |

| CA | 0644 | 225.41 | LA | 2201 | 313.23 | NY | 3622 | 270.59 | TX | 4823 | 226.97 |

| CA | 0645 | 225.51 | LA | 2202 | 341.56 | NY | 3623 | 278.23 | TX | 4824 | 275.61 |

| CA | 0646 | 226.08 | LA | 2203 | 317.11 | NY | 3624 | 257.38 | TX | 4825 | 276.05 |

| CA | 0647 | 224.82 | LA | 2204 | 314.28 | NY | 3625 | 266.60 | TX | 4826 | 250.08 |

| CA | 0648 | 224.82 | LA | 2205 | 321.98 | NY | 3626 | 270.45 | TX | 4827 | 229.00 |

| CA | 0649 | 232.00 | LA | 2206 | 302.08 | NY | 3627 | 271.37 | TX | 4828 | 231.66 |

| CA | 0650 | 235.70 | LA | 2207 | 307.17 | NY | 3628 | 268.37 | TX | 4829 | 277.95 |

| CA | 0651 | 235.62 | ME | 2301 | 272.57 | NY | 3629 | 268.26 | TX | 4830 | 279.05 |

| CA | 0652 | 235.70 | ME | 2302 | 291.59 | NC | 3701 | 325.75 | TX | 4831 | 258.48 |

| CA | 0653 | 235.70 | MD | 2401 | 293.67 | NC | 3702 | 307.11 | TX | 4832 | 279.05 |

| CO | 0801 | 247.17 | MD | 2402 | 300.57 | NC | 3703 | 312.42 | UT | 4901 | 188.85 |

| CO | 0802 | 216.40 | MD | 2403 | 306.03 | NC | 3704 | 276.61 | UT | 4902 | 194.50 |

| CO | 0803 | 218.01 | MD | 2404 | 261.33 | NC | 3705 | 270.43 | UT | 4903 | 186.38 |

| CO | 0804 | 217.45 | MD | 2405 | 293.74 | NC | 3706 | 269.53 | VT | 5099 | 262.46 |

| CO | 0805 | 230.10 | MD | 2406 | 268.50 | NC | 3707 | 303.46 | VA | 5101 | 294.08 |

| CO | 0806 | 205.15 | MD | 2407 | 331.59 | NC | 3708 | 295.65 | VA | 5102 | 291.22 |

| CO | 0807 | 223.10 | MD | 2408 | 212.85 | NC | 3709 | 280.84 | VA | 5103 | 335.68 |

| CT | 0901 | 252.15 | MA | 2501 | 266.20 | NC | 3710 | 283.71 | VA | 5104 | 321.70 |

| CT | 0902 | 255.68 | MA | 2502 | 273.91 | NC | 3711 | 251.18 | VA | 5105 | 278.86 |

| CT | 0903 | 253.05 | MA | 2503 | 272.89 | NC | 3712 | 273.38 | VA | 5106 | 270.54 |

| CT | 0904 | 237.15 | MA | 2504 | 275.28 | NC | 3713 | 274.86 | VA | 5107 | 289.48 |

| CT | 0905 | 246.80 | MA | 2505 | 268.96 | ND | 3899 | 243.02 | VA | 5108 | 228.11 |

| DE | 1099 | 289.44 | MA | 2506 | 270.11 | OH | 3901 | 295.76 | VA | 5109 | 274.86 |

| DC | 1198 | 343.78 | MA | 2507 | 271.96 | OH | 3902 | 293.68 | VA | 5110 | 258.25 |

| FL | 1201 | 287.59 | MA | 2508 | 295.36 | OH | 3903 | 284.95 | VA | 5111 | 231.79 |

| FL | 1202 | 287.22 | MA | 2509 | 283.39 | OH | 3904 | 274.64 | WA | 5301 | 245.00 |

| FL | 1203 | 285.46 | MA | 2510 | 269.84 | OH | 3905 | 262.93 | WA | 5302 | 234.80 |

| FL | 1204 | 316.89 | MI | 2601 | 261.34 | OH | 3906 | 287.57 | WA | 5303 | 255.32 |

| FL | 1205 | 256.17 | MI | 2602 | 248.17 | OH | 3907 | 276.90 | WA | 5304 | 240.69 |

| FL | 1206 | 281.19 | MI | 2603 | 245.36 | OH | 3908 | 271.26 | WA | 5305 | 246.75 |

| FL | 1207 | 262.33 | MI | 2604 | 260.27 | OH | 3909 | 287.34 | WA | 5306 | 260.08 |

| FL | 1208 | 262.72 | MI | 2605 | 278.91 | OH | 3910 | 293.92 | WA | 5307 | 239.57 |

| FL | 1209 | 265.45 | MI | 2606 | 266.81 | OH | 3911 | 293.92 | WA | 5308 | 244.02 |

| FL | 1210 | 249.68 | MI | 2607 | 263.88 | OH | 3912 | 281.32 | WA | 5309 | 249.13 |

| FL | 1211 | 277.62 | MI | 2608 | 253.12 | OH | 3913 | 277.94 | WV | 5401 | 278.03 |

| FL | 1212 | 265.00 | MI | 2609 | 247.44 | OH | 3914 | 266.04 | WV | 5402 | 296.32 |

| FL | 1213 | 225.69 | MI | 2610 | 272.66 | OH | 3915 | 293.41 | WV | 5403 | 298.58 |

| FL | 1214 | 215.92 | MI | 2611 | 284.77 | OH | 3916 | 259.50 | WI | 5501 | 265.84 |

| FL | 1215 | 252.94 | MI | 2612 | 263.76 | OH | 3917 | 272.68 | WI | 5502 | 235.97 |

| FL | 1216 | 236.00 | MI | 2613 | 300.81 | OH | 3918 | 280.22 | WI | 5503 | 244.95 |

| FL | 1217 | 238.61 | MI | 2614 | 300.81 | OK | 4001 | 270.44 | WI | 5504 | 285.86 |

| FL | 1218 | 239.87 | MI | 2615 | 272.06 | OK | 4002 | 295.23 | WI | 5505 | 247.27 |

| FL | 1219 | 225.47 | MN | 2701 | 234.69 | OK | 4003 | 252.79 | WI | 5506 | 248.00 |

| FL | 1220 | 241.08 | MN | 2702 | 232.60 | OK | 4004 | 263.30 | WI | 5507 | 253.68 |

| FL | 1221 | 237.96 | MN | 2703 | 246.78 | OK | 4005 | 273.49 | WI | 5508 | 252.81 |

| FL | 1222 | 228.26 | MN | 2704 | 253.04 | OR | 4101 | 239.29 | WY | 5699 | 240.61 |

Table 2.

Age-adjusted death rates, all cancers combined, for US women by congressional district (CD), 1990–2001

| State | CD | Rate | State | CD | Rate | State | CD | Rate | State | CD | Rate |

| AL | 0101 | 178.15 | FL | 1223 | 166.84 | MN | 2705 | 167.95 | OR | 4102 | 167.81 |

| AL | 0102 | 169.16 | FL | 1224 | 171.40 | MN | 2706 | 159.96 | OR | 4103 | 181.38 |

| AL | 0103 | 173.01 | FL | 1225 | 148.24 | MN | 2707 | 149.49 | OR | 4104 | 175.60 |

| AL | 0104 | 160.11 | GA | 1301 | 171.36 | MN | 2708 | 167.49 | OR | 4105 | 170.49 |

| AL | 0105 | 158.39 | GA | 1302 | 164.99 | MS | 2801 | 163.41 | PA | 4201 | 216.57 |

| AL | 0106 | 166.72 | GA | 1303 | 160.00 | MS | 2802 | 178.71 | PA | 4202 | 217.49 |

| AL | 0107 | 173.12 | GA | 1304 | 158.33 | MS | 2803 | 162.39 | PA | 4203 | 171.06 |

| AK | 0299 | 177.59 | GA | 1305 | 174.21 | MS | 2804 | 173.19 | PA | 4204 | 177.43 |

| AZ | 0401 | 150.54 | GA | 1306 | 168.46 | MO | 2901 | 184.42 | PA | 4205 | 167.87 |

| AZ | 0402 | 160.42 | GA | 1307 | 156.76 | MO | 2902 | 172.86 | PA | 4206 | 170.48 |

| AZ | 0403 | 155.51 | GA | 1308 | 166.01 | MO | 2903 | 191.43 | PA | 4207 | 185.30 |

| AZ | 0404 | 155.51 | GA | 1309 | 160.49 | MO | 2904 | 167.09 | PA | 4208 | 182.33 |

| AZ | 0405 | 155.51 | GA | 1310 | 158.41 | MO | 2905 | 180.75 | PA | 4209 | 162.09 |

| AZ | 0406 | 154.84 | GA | 1311 | 168.71 | MO | 2906 | 167.65 | PA | 4210 | 169.23 |

| AZ | 0407 | 143.81 | GA | 1312 | 169.92 | MO | 2907 | 166.90 | PA | 4211 | 175.65 |

| AZ | 0408 | 155.45 | GA | 1313 | 166.59 | MO | 2908 | 173.10 | PA | 4212 | 169.55 |

| AR | 0501 | 176.39 | HI | 1501 | 132.18 | MO | 2909 | 168.23 | PA | 4213 | 195.46 |

| AR | 0502 | 167.22 | HI | 1502 | 132.18 | MT | 3099 | 164.72 | PA | 4214 | 185.54 |

| AR | 0503 | 159.68 | ID | 1601 | 159.32 | NE | 3101 | 154.37 | PA | 4215 | 167.46 |

| AR | 0504 | 171.75 | ID | 1602 | 145.79 | NE | 3102 | 172.54 | PA | 4216 | 166.84 |

| CA | 0601 | 180.93 | IL | 1701 | 187.65 | NE | 3103 | 148.99 | PA | 4217 | 171.04 |

| CA | 0602 | 179.84 | IL | 1702 | 187.39 | NV | 3201 | 185.55 | PA | 4218 | 179.77 |

| CA | 0603 | 173.30 | IL | 1703 | 187.65 | NV | 3202 | 178.47 | PA | 4219 | 164.61 |

| CA | 0604 | 171.91 | IL | 1704 | 187.65 | NV | 3203 | 185.55 | RI | 4401 | 176.99 |

| CA | 0605 | 174.43 | IL | 1705 | 187.65 | NH | 3301 | 184.05 | RI | 4402 | 181.40 |

| CA | 0606 | 174.68 | IL | 1706 | 171.34 | NH | 3302 | 177.78 | SC | 4501 | 168.40 |

| CA | 0607 | 172.79 | IL | 1707 | 187.65 | NJ | 3401 | 197.38 | SC | 4502 | 169.68 |

| CA | 0608 | 160.82 | IL | 1708 | 183.94 | NJ | 3402 | 194.20 | SC | 4503 | 160.68 |

| CA | 0609 | 171.62 | IL | 1709 | 187.65 | NJ | 3403 | 187.01 | SC | 4504 | 163.56 |

| CA | 0610 | 171.36 | IL | 1710 | 184.25 | NJ | 3404 | 189.04 | SC | 4505 | 170.43 |

| CA | 0611 | 166.00 | IL | 1711 | 176.79 | NJ | 3405 | 181.48 | SC | 4506 | 170.50 |

| CA | 0612 | 163.35 | IL | 1712 | 182.42 | NJ | 3406 | 189.45 | SD | 4699 | 155.91 |

| CA | 0613 | 171.63 | IL | 1713 | 170.69 | NJ | 3407 | 175.40 | TN | 4701 | 163.70 |

| CA | 0614 | 155.60 | IL | 1714 | 173.48 | NJ | 3408 | 186.04 | TN | 4702 | 166.03 |

| CA | 0615 | 150.41 | IL | 1715 | 169.81 | NJ | 3409 | 179.94 | TN | 4703 | 170.24 |

| CA | 0616 | 150.41 | IL | 1716 | 173.31 | NJ | 3410 | 190.31 | TN | 4704 | 166.86 |

| CA | 0617 | 159.08 | IL | 1717 | 169.35 | NJ | 3411 | 178.32 | TN | 4705 | 181.74 |

| CA | 0618 | 167.37 | IL | 1718 | 175.46 | NJ | 3412 | 185.32 | TN | 4706 | 166.05 |

| CA | 0619 | 160.90 | IL | 1719 | 171.91 | NJ | 3413 | 185.44 | TN | 4707 | 171.72 |

| CA | 0620 | 160.07 | IN | 1801 | 187.73 | NM | 3501 | 152.60 | TN | 4708 | 172.99 |

| CA | 0621 | 155.17 | IN | 1802 | 174.13 | NM | 3502 | 148.21 | TN | 4709 | 191.57 |

| CA | 0622 | 167.90 | IN | 1803 | 171.04 | NM | 3503 | 145.39 | TX | 4801 | 170.48 |

| CA | 0623 | 156.79 | IN | 1804 | 175.19 | NY | 3601 | 193.45 | TX | 4802 | 179.62 |

| CA | 0624 | 159.18 | IN | 1805 | 174.37 | NY | 3602 | 192.13 | TX | 4803 | 158.43 |

| CA | 0625 | 165.29 | IN | 1806 | 173.27 | NY | 3603 | 180.21 | TX | 4804 | 171.21 |

| CA | 0626 | 167.46 | IN | 1807 | 195.50 | NY | 3604 | 175.92 | TX | 4805 | 174.87 |

| CA | 0627 | 163.44 | IN | 1808 | 174.00 | NY | 3605 | 159.07 | TX | 4806 | 173.74 |

| CA | 0628 | 163.44 | IN | 1809 | 174.32 | NY | 3606 | 154.59 | TX | 4807 | 174.78 |

| CA | 0629 | 163.44 | IA | 1901 | 167.19 | NY | 3607 | 167.00 | TX | 4808 | 175.14 |

| CA | 0630 | 163.44 | IA | 1902 | 160.01 | NY | 3608 | 169.61 | TX | 4809 | 184.12 |

| CA | 0631 | 163.44 | IA | 1903 | 166.60 | NY | 3609 | 157.90 | TX | 4810 | 161.79 |

| CA | 0632 | 163.44 | IA | 1904 | 155.81 | NY | 3610 | 165.33 | TX | 4811 | 162.37 |

| CA | 0633 | 163.44 | IA | 1905 | 158.63 | NY | 3611 | 165.35 | TX | 4812 | 173.24 |

| CA | 0634 | 163.44 | KS | 2001 | 150.79 | NY | 3612 | 164.75 | TX | 4813 | 166.63 |

| CA | 0635 | 163.44 | KS | 2002 | 164.11 | NY | 3613 | 180.01 | TX | 4814 | 161.32 |

| CA | 0636 | 163.44 | KS | 2003 | 162.29 | NY | 3614 | 168.07 | TX | 4815 | 130.06 |

| CA | 0637 | 163.44 | KS | 2004 | 167.47 | NY | 3615 | 173.80 | TX | 4816 | 150.47 |

| CA | 0638 | 163.44 | KY | 2101 | 169.41 | NY | 3616 | 175.64 | TX | 4817 | 163.78 |

| CA | 0639 | 163.44 | KY | 2102 | 175.24 | NY | 3617 | 173.76 | TX | 4818 | 174.78 |

| CA | 0640 | 158.89 | KY | 2103 | 193.34 | NY | 3618 | 170.09 | TX | 4819 | 158.33 |

| CA | 0641 | 171.99 | KY | 2104 | 188.93 | NY | 3619 | 184.37 | TX | 4820 | 159.07 |

| CA | 0642 | 162.99 | KY | 2105 | 194.13 | NY | 3620 | 182.40 | TX | 4821 | 156.84 |

| CA | 0643 | 173.93 | KY | 2106 | 182.99 | NY | 3621 | 181.17 | TX | 4822 | 163.94 |

| CA | 0644 | 162.59 | LA | 2201 | 185.99 | NY | 3622 | 184.58 | TX | 4823 | 145.28 |

| CA | 0645 | 163.17 | LA | 2202 | 195.03 | NY | 3623 | 181.55 | TX | 4824 | 173.40 |

| CA | 0646 | 160.07 | LA | 2203 | 183.13 | NY | 3624 | 172.75 | TX | 4825 | 173.48 |

| CA | 0647 | 158.89 | LA | 2204 | 181.02 | NY | 3625 | 177.64 | TX | 4826 | 166.78 |

| CA | 0648 | 158.89 | LA | 2205 | 178.98 | NY | 3626 | 178.41 | TX | 4827 | 145.93 |

| CA | 0649 | 165.98 | LA | 2206 | 180.49 | NY | 3627 | 181.68 | TX | 4828 | 145.40 |

| CA | 0650 | 167.74 | LA | 2207 | 187.87 | NY | 3628 | 178.66 | TX | 4829 | 174.78 |

| CA | 0651 | 164.39 | ME | 2301 | 184.93 | NY | 3629 | 181.02 | TX | 4830 | 173.69 |

| CA | 0652 | 167.74 | ME | 2302 | 183.09 | NC | 3701 | 174.50 | TX | 4831 | 160.07 |

| CA | 0653 | 167.74 | MD | 2401 | 188.54 | NC | 3702 | 165.66 | TX | 4832 | 173.69 |

| CO | 0801 | 162.28 | MD | 2402 | 192.89 | NC | 3703 | 174.10 | UT | 4901 | 123.40 |

| CO | 0802 | 153.27 | MD | 2403 | 196.95 | NC | 3704 | 170.87 | UT | 4902 | 131.73 |

| CO | 0803 | 147.33 | MD | 2404 | 174.28 | NC | 3705 | 155.94 | UT | 4903 | 127.35 |

| CO | 0804 | 147.02 | MD | 2405 | 189.44 | NC | 3706 | 162.13 | VT | 5099 | 172.62 |

| CO | 0805 | 153.67 | MD | 2406 | 169.34 | NC | 3707 | 168.11 | VA | 5101 | 180.85 |

| CO | 0806 | 153.08 | MD | 2407 | 205.58 | NC | 3708 | 169.12 | VA | 5102 | 184.69 |

| CO | 0807 | 153.73 | MD | 2408 | 150.96 | NC | 3709 | 168.36 | VA | 5103 | 197.48 |

| CT | 0901 | 167.11 | MA | 2501 | 174.47 | NC | 3710 | 157.81 | VA | 5104 | 186.12 |

| CT | 0902 | 169.98 | MA | 2502 | 178.16 | NC | 3711 | 158.78 | VA | 5105 | 163.70 |

| CT | 0903 | 172.06 | MA | 2503 | 178.00 | NC | 3712 | 166.97 | VA | 5106 | 163.67 |

| CT | 0904 | 167.64 | MA | 2504 | 179.23 | NC | 3713 | 165.79 | VA | 5107 | 176.21 |

| CT | 0905 | 167.56 | MA | 2505 | 179.67 | ND | 3899 | 156.30 | VA | 5108 | 165.17 |

| DE | 1099 | 190.49 | MA | 2506 | 179.61 | OH | 3901 | 193.84 | VA | 5109 | 166.02 |

| DC | 1198 | 203.38 | MA | 2507 | 181.29 | OH | 3902 | 190.45 | VA | 5110 | 170.94 |

| FL | 1201 | 170.38 | MA | 2508 | 190.60 | OH | 3903 | 185.18 | VA | 5111 | 168.97 |

| FL | 1202 | 177.20 | MA | 2509 | 188.59 | OH | 3904 | 171.76 | WA | 5301 | 171.78 |

| FL | 1203 | 180.69 | MA | 2510 | 184.62 | OH | 3905 | 164.79 | WA | 5302 | 169.26 |

| FL | 1204 | 187.94 | MI | 2601 | 170.39 | OH | 3906 | 179.70 | WA | 5303 | 176.09 |

| FL | 1205 | 165.25 | MI | 2602 | 161.41 | OH | 3907 | 182.23 | WA | 5304 | 163.04 |

| FL | 1206 | 174.62 | MI | 2603 | 163.09 | OH | 3908 | 177.92 | WA | 5305 | 166.08 |

| FL | 1207 | 170.67 | MI | 2604 | 164.71 | OH | 3909 | 184.70 | WA | 5306 | 180.48 |

| FL | 1208 | 172.08 | MI | 2605 | 177.98 | OH | 3910 | 188.77 | WA | 5307 | 166.68 |

| FL | 1209 | 168.29 | MI | 2606 | 172.69 | OH | 3911 | 188.77 | WA | 5308 | 169.06 |

| FL | 1210 | 159.50 | MI | 2607 | 173.30 | OH | 3912 | 187.23 | WA | 5309 | 171.64 |

| FL | 1211 | 172.59 | MI | 2608 | 169.43 | OH | 3913 | 180.65 | WV | 5401 | 178.91 |

| FL | 1212 | 160.52 | MI | 2609 | 171.89 | OH | 3914 | 177.31 | WV | 5402 | 186.23 |

| FL | 1213 | 150.69 | MI | 2610 | 175.35 | OH | 3915 | 191.61 | WV | 5403 | 191.78 |

| FL | 1214 | 144.66 | MI | 2611 | 185.66 | OH | 3916 | 168.52 | WI | 5501 | 173.85 |

| FL | 1215 | 166.13 | MI | 2612 | 173.14 | OH | 3917 | 174.30 | WI | 5502 | 160.12 |

| FL | 1216 | 159.77 | MI | 2613 | 191.34 | OH | 3918 | 176.73 | WI | 5503 | 156.93 |

| FL | 1217 | 155.30 | MI | 2614 | 191.34 | OK | 4001 | 174.42 | WI | 5504 | 183.35 |

| FL | 1218 | 152.52 | MI | 2615 | 181.41 | OK | 4002 | 175.25 | WI | 5505 | 164.99 |

| FL | 1219 | 163.40 | MN | 2701 | 150.21 | OK | 4003 | 157.63 | WI | 5506 | 163.77 |

| FL | 1220 | 167.15 | MN | 2702 | 161.35 | OK | 4004 | 162.63 | WI | 5507 | 158.81 |

| FL | 1221 | 152.17 | MN | 2703 | 167.91 | OK | 4005 | 175.18 | WI | 5508 | 157.81 |

| FL | 1222 | 164.56 | MN | 2704 | 172.77 | OR | 4101 | 169.53 | WY | 5699 | 164.81 |

Historically, female breast cancer death rates have been elevated in the Northeastern and North Central regions; North-South differences have diminished over time as female breast cancer death rates decreased in the Northeast but increased in the South [8]. For all races combined, female breast cancer death rates vary from 20.6 in Hawaii to 39.4 in District of Columbia. Among African American women, breast cancer death rates are highest in congressional districts in the south, Midwest, and west coast, while among non-Hispanic whites, breast cancer mortality is highest in congressional districts in the Northeast and west coast (Figure 4, right panel). Patterns of breast cancer mortality partly reflect the influence of known risk factors as well as access to and utilization of cancer screening and treatment. Important cancer control measures include access to mammography for the uninsured and under-insured, and availability of Medicaid coverage for diagnosis and treatment.

Colorectal cancer death rates are highest overall in the Northeast and parts of the South and Midwest. Generally, death rates range from 18.4 in Texas congressional district #15 to 37.1 in Pennsylvania congressional district #1 for men and from 11.3 in Texas congressional district #15 to 24.1 in District of Columbia for women (Figure 3). Although a strong geographic pattern for colorectal cancer mortality has existed since the 1950's, the reasons are not well-understood [1]. The current priority for colorectal cancer control is to increase the proportion of individuals over 50 who receive recommended screening tests. Illustrating colorectal cancer mortality by legislative district may be influential in encouraging legislative support for mandated insurance coverage of colorectal screening tests and for programs to provide testing for the uninsured and under-insured.

For all races combined, prostate cancer death rates range from 23.8 in Texas congressional district #15 and Hawaii to 58.2 in District of Columbia. Generally, rates are highest in congressional districts in the mid-Atlantic and Southern coastal areas, reflecting in large part the higher proportion of the African American men in the population of these areas (Figure 4, left panel). Death rates for African American men are more than twice the rates for non-Hispanic white men, reflecting higher incidence, later stage at diagnosis and poorer survival among African American men. Among non-Hispanic whites, rates are highest in congressional districts in the Rocky Mountain region; high rate (40.2) is observed in Hispanics in Texas congressional district #13. A recent study suggested that 10% to 30% of the geographic variation in prostate cancer death rates might relate to variations in access to medical care [9]. Although cancer control measures for prostate cancer are less well-defined than measures for some other cancer sites, illustrating prostate cancer mortality by congressional district may be helpful in advocating for funding of research on the prevention, early detection and treatment of prostate cancer and highlighting the importance of access to medical care for African American men.

Mortality from cervical cancer in all races combined is highest in congressional districts in Appalachia, in the South and parts of the Southwest, with rates ranging from 1.4 in Minnesota congressional district #2 to 5.7 in New York congressional district #16 (Figure 5). Among African American women, rates are highest in congressional districts in the south and southeast, among non-Hispanic whites, rates are highest in congressional districts in Appalachia, and in Hispanics rates are highest in congressional districts in the coastal parts of California and Texas and in Colorado congressional district #3. Important cancer control measures include access to Pap tests for the uninsured and under-insured, and availability of Medicaid coverage for diagnosis and treatment.

Conclusion

The cancer mortality patterns by congressional district are generally similar to the patterns seen using other geographic boundaries. However, the patterns by congressional district may be useful to cancer control advocates to illustrate the importance of cancer control measures (prevention, early detection, and treatment) for their constituents. The method can be applied to state legislative districts and other analyses that involve data aggregation from different geographic units. Further research is needed to validate the estimates using mortality data geocoded to the lower geographic level such as block.

Methods

Death rates for U.S. states and counties

Mortality data were obtained from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). We computed annual average age-adjusted death rates for all cancer sites combined, the four major cancers (lung and bronchus, prostate, female breast, and colorectal cancer) and cervical cancer from 1990–2001 for 50 states, District of Columbia, and all counties using SEER*Stat [10]. Death rates, counts (number of deaths), and populations for counties were directly obtained for men and women, for all races combined, and for African Americans, non-Hispanic whites, and Hispanics. Except for the years of 1990 and 2000, the intercensal populations computed by the Census Bureau were used to obtain the total populations for the study time period. Since county designation for Alaska and Hawaii was not available from NCHS, death rates for Alaska and Hawaii reflect state rates. Rates were standardized to the 2000 U.S. population and expressed per 100,000 person-years.

Death rates for U.S. congressional districts

There are 436 (excluding Puerto Rico) federal congressional districts in the U.S. [11]. Among these, eight congressional districts followed state boundaries or their equivalent (Alaska, District of Columbia, Delaware, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming). Further, since county-specific mortality data were not provided for Hawaii in SEER*Stat, we assigned the state death rate to both congressional districts. For congressional districts whose boundaries did not follow state and county boundaries (n = 426), death rates were calculated by assigning county-level age-adjusted death rates to census block and then aggregating death rates over blocks by congressional district using GIS [12] and SAS [13]. By doing so, we assume that blocks within a county have same death rates.

There are three major areal interpolation methods (area weighting, surface smoothing, and dasymetric technique) for generating estimates for target zones from data available for source zones when the two geographic units are not comparable. Areal weighting assumes that data are homogeneously distributed across geographic units, which is generally unrealistic; it also involves the direct superimposition of source zones and target zones [14], which often leads to a lot of geographic boundary-line discrepancies [15]. Surface smoothing models data available for source zones as a continuous surface across the adjacent zones, assuming that the density declines with distance, taking into account the proximity of neighboring centroids [16,17]. Dasymetric technique uses ancillary information to refine uneven data distributions across geographic units. Land cover from remote sensing [18] and the street layer [15,19] have been used as subzone ancillary information. A recent study uses parish level (the lowest administrative unit) population data to derive weights [20]. However, there is no universal rule to construct areal interpolation, and the best solution depends on various factors: the variables of interest, the spatial relationships between source zones and target zones, and the availability of ancillary information related to both.

In this study, we constructed a dasymetric method based on the hierarchical spatial relationships between blocks and counties and between blocks and congressional districts. Generally, congressional district and county share census block as a common basic spatial unit (Table 3) [21,22]. We used block level sex- and race- specific population to devise a dasymetric approach that assigns county-level measures such as cancer death rates to census block and then aggregates census blocks at the congressional district level, using block population as a weighting factor. We did not use area weighting because of its unrealistic homogeneity assumption and boundary-line discrepancies associated with direct superimposition of two incomparable geographic units. Surface smoothing gives reliable estimates when smoothness is the real property of the density. However, the occurrence of cancer rarely follows a smooth distance-decay surface because major risk factors that affect cancer occurrence do not have smooth paths from the centroid to its adjacent neighboring centroids.

Table 3.

The hierarchical spatial relationships between blocks and counties and between blocks and congressional districts

| County | Block | Congressional district |

| County A | Block A1 | |

| Block A2 | ||

| Block A3 | ||

| Congressional district #1 | ||

| ... | ||

| County B | Block B1 | |

| Block B2 | ||

| Block B3 | ||

| ... | ||

| County C | Block C1 | Congressional district #2 |

| Block C2 | ||

| Block C3 | ||

| ... | ||

| ... | ... | ... |

To make the calculations, the following steps were taken:

1. The number of people living within each census block by sex and race was determined from the 2000 U.S. census (covering 42 states, 426 congressional districts). Therefore, block population is sex- and race- specific.

2. Block population was spatially assigned to congressional districts by block centroids.

3. The age-adjusted cancer death rates for counties by sex and race were assigned to block by county FIPS (Federal Information Processing Standards) codes; FIPS codes are a standardized set of numeric or alphabetic codes issued by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) to ensure uniform identification of geographic entities through all federal government agencies [23].

4. Cancer death rate for each congressional district by sex and race was calculated by aggregating sex- and race- specific cancer death rates over blocks. Taking non-Hispanic white men as an example, suppose that ri was the age-adjusted cancer death rate for block i (obtained from the corresponding county rate calculated from SEER*Stat). Suppose that aij was the population of block i within district j, and that the population for district j,  , were known. Then the aggregated cancer death rate for district j, pj, was the summation of ri, weighted by the proportion of block population within the district,

, were known. Then the aggregated cancer death rate for district j, pj, was the summation of ri, weighted by the proportion of block population within the district, . Other sex- and race-specific cancer death rates were calculated similarly.

. Other sex- and race-specific cancer death rates were calculated similarly.

5. The number of cancer deaths for each congressional district by sex and race was calculated by aggregating the sex- and race- specific number of cancer deaths over blocks. The number of cancer deaths for a block was the product of crude death rate for the block (inherited from the corresponding county, which is the number of deaths for the county divided by the county population) and the block population. Again, taking non-Hispanic white men as an example, suppose that ni and ci were the number of deaths and the population for the county to which block i belongs, the crude death rate for block i was  . Given aij was the population of block i within district j, then the number of deaths for block i within district j was

. Given aij was the population of block i within district j, then the number of deaths for block i within district j was  aij, and the aggregated number of deaths for district j was

aij, and the aggregated number of deaths for district j was  . Other sex- and race- specific number of cancer deaths were calculated in a similar way.

. Other sex- and race- specific number of cancer deaths were calculated in a similar way.

6. The aggregated cancer death rates and the number of cancer deaths for the congressional districts (n = 426) from step 4 & 5 were exported back to GIS and linked with the other ten congressional districts (Alaska, District of Columbia, Delaware, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, Wyoming, and two Hawaii districts) for producing maps. The estimates of the number of deaths were not presented separately. Instead, they were used as the criteria when mapping death rates across congressional districts. Death rates based on the small number of deaths (< 20) for the study time period were considered not reliable and thus excluded.

7. Maps were generated using ArcGIS [12]. For all cancer sites combined and for each cancer site, the maps for all races combined were created by categorizing the rates into five groups. Cut points for the lowest and highest groups are approximately the 10th and 90th percentiles, except for cervical cancer which are 20th and 80th percentiles. Intervening groups are set at equal length between the lower bound cut point of 90th or 80th and the upper bound of 10th or 20th. Thus each interval represents the same absolute change over the middle range of rates, while the most extreme rates fall into the first and fifth categories. For each cancer site, to allow comparison among ethnic subgroups, the cut points for all races combined are used for race specific maps if rates are in the same range as those for all races combined. When the race specific rates fall out of the range of rates for all races combined, cut points for the exceeded portion are equally set at the length of rates in the highest category for all races combined. Cancer death rates based on the small number of deaths (< 20) are considered unstable and congressional districts with such rates are marked with hatches.

In describing the cancer burden by congressional district, we used direct age adjustment instead of indirect age adjustment because direct method is more statistically correct when the rates are being compared [24]. Direct age-adjusted death rates describe the cancer death rate each congressional district would have if it had the age-sex-race distribution of the U.S. in the year 2000. In so far as congressional districts have age-sex-race compositions different from the U.S. in 2000, the need for resources to eliminate disparities between districts might be more or less than that suggested by the results described in this paper.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

YH, EMW, and AJ conceived the analysis and wrote the final version of the manuscript. LWP provided technical support on the method and critically revised the manuscript. MJT conceptualized and critically revised the manuscript.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of the National Cancer Institute.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Lance A Waller from Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University for his comments and suggestions on the early version of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Yongping Hao, Email: yongping.hao@cancer.org.

Elizabeth M Ward, Email: elizabeth.ward@cancer.org.

Ahmedin Jemal, Email: ahmedin.jemal@cancer.org.

Linda W Pickle, Email: picklel@mail.nih.gov.

Michael J Thun, Email: michael.thun@cancer.org.

References

- Devesa SS, Grauman DJ, Bolt WJ, Pennello GA, Hoover RN, Fraumeni JFJ. Atlas of cancer mortality in the United States, 1950-94. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute , NIH Publication No. 99-4564; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman HP, Wingrove BK. Excess Cervical Cancer Mortality: A Marker for Low Access to Health Care in Poor Communities. Rockville, MD: National Cancer Institute, Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities , NIH Pub No. 05-5282; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society . Cancer Facts and Figures 2006. Atlanta , American Cancer Society; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hu TW, Bai J, Keeler TE, Barnett PG, Sung HY. The impact of California Proposition 99, a major anti-smoking law, on cigarette consumption. J Public Health Policy. 1994;15:26–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier KJ, Licari MJ. The effect of cigarette taxes on cigarette consumption, 1955 through 1994. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1126–1130. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.7.1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson DE, Zeger SL, Remington PL, Anderson HA. The effect of state cigarette tax increases on cigarette sales, 1955 to 1988. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:94–96. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.1.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haenzsel W, M.B. S, Miller HP. Public Health Monograpah 45. Washington (DC) , US Government Print Off; 1955. Tobacco smoking patterns in the United States. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturgeon SR, Schairer C, Grauman D, El Ghormli L, Devesa S. Trends in breast cancer mortality rates by region of the United States, 1950-1999. Cancer Causes Control. 2004;15:987–995. doi: 10.1007/s10552-004-1092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Ward E, Wu X, Martin HJ, McLaughlin CC, Thun MJ. Geographic patterns of prostate cancer mortality and variations in access to medical care in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:590–595. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute Cancer Statistics Branch DCCPS Surveillance Research Program . Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (www.seer.cancer.gov) SEER*Stat Database: Incidence - SEER 9 Regs Public-Use, Nov 2003 Sub (1973-2001) Bethesda, MD; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau . 108th Congressional District Summary Files, United States Census 2000. V1-D00-C108-08-US1 http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/2003/108th.html [Google Scholar]

- Environmental Science and Research Institute (ESRI) ArcGIS Software for Windows [computer program]. Version 9.0. Redlands, CA , Environmental Science and Research Institute (ESRI); 2005. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute INC. SAS-Statistical Analysis Software for Windows [computer program]. Version 9.0. Cary, NC , SAS Institute INC.; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Flowerdew R, Green M. Developments in areal interpolation methods and GIS. Annals of Regional Science. 1992;26:67–78. doi: 10.1007/BF01581481. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reibel M, Bufalino ME. Street-weighted interpolation techniques for demographic count estimation in incompatible zone systems. Environment and Planning A. 2005;37:127–139. doi: 10.1068/a36202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin D. An assessment of surface and zonal models of population. International Journal of Geographical Information Systems. 1996;10:973–989. doi: 10.1080/026937996137684. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tobler WR. Smooth Pycnophylactic Interpolation for Geographical Regions. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1979;74:519–530. doi: 10.2307/2286968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennis J. Generating surface models of population using dasymetric mapping. Professional Geographer. 2003;55:31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Xie YC. The overlaid network algorithms for areal interpolation problem. Computers Environment and Urban Systems. 1995;19:287–306. doi: 10.1016/0198-9715(95)00028-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory IN, Ell PS. Breaking the boundaries: Geographical approaches to integrating 200 years of the census. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series a-Statistics in Society. 2005;168:419–437. [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau Hierarchical relationship of census geographic entities http://www.census.gov/geo/www/cengeoga.pdf

- US Census Bureau TIGER®, TIGER/Line® and TIGER-Related Products http://www.census.gov/geo/www/tiger/tgrcd108/spblk108.txt

- US Census Bureau Federal Information Processing Standards (FIPS) Codes http://www.census.gov/geo/www/fips/fips.html

- Pickle LW, White AA. Effects of the choice of age-adjustment method on maps of death rates. Stat Med. 1995;14:615–627. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780140519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]