Abstract

Mice deficient in RNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR–/–) or deficient in PKR and a functional 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthetase (OAS) pathway (PKR/RL–/–) are more susceptible to genital herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) infection than wild-type mice or mice that are deficient only in a functional OAS pathway (RL–/–) as measured by survival over 30 days. The increase in susceptibility correlated with an increase in virus titre recovered from vaginal tissue or brainstem of infected mice during acute infection. There was also an increase in CD45+ cells and CD8+ T cells residing in the central nervous system of HSV-2-infected PKR/RL–/– mice in comparison with RL–/– or wild-type control animals. In contrast, there was a reduction in the HSV-specific CD8+ T cells within the draining lymph node of the PKR/RL–/– mice. Collectively, activation of PKR, but not of OAS, contributes significantly to the local control and spread of HSV-2 following genital infection.

Keywords: CD8+ T cell, herpes simplex virus type 2, interferon-γ, oligoadenylate synthetases, RNA-dependent protein kinase

Introduction

Over 1·6 million Americans are infected with herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) annually, the major causative agent of genital herpes.1 Although both HSV-1 and HSV-2 can infect the genital tract, HSV-2 infection is more severe with an increase in the frequency of recurrences.2 Complications following primary genital herpetic infection include sacral radiculomyelitis, which can lead to urinary retention, neuralgias and meningoencephalitis. Following the acute infection lasting 7–21 days, the virus will establish a latent infection within the neurons of the sensory ganglia (sacral ganglia) and will periodically reactivate with clinical and subclinical presentation.

In response to the initial infection, natural killer (NK) cells, NKT cells, and neutrophils are recruited to the area along with the production of a number of soluble factors including interleukin-12 (IL-12), IL-15 and IL-18, all of which are found to contribute to the innate defence against HSV-2.3–6 In addition, recognition by toll-like receptor 9 of HSV-2 DNA leads to the production by plasmacytoid dendritic cells of type I interferons (IFNs),7 a family of antiviral cytokines that have been found to suppress genital HSV-2 replication in vivo.8 Even though a robust innate immune response ensues, HSV-2 can successfully infect and replicate in the host. Contributing to the success of the virus in evading the host response is the tegument protein, virion host shutoff protein, which has been implicated in the reduction of major histocompatibility class I expression.9 It has also been found to counter the type I IFN responses.10

The replication of HSV-2 is significantly reduced in cells pretreated with type I IFNs,11 and fibroblasts deficient in a functional oligoadenylate synthetase (OAS) or RNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR) pathway do not respond to exogenous IFN-α in suppressing HSV-2 replication, implicating these IFN-responsive pathways in the control of the virus.12 The present investigation sought to define further the role of IFN-responsive pathways focusing on OAS and PKR in response to genital HSV-2 infection.

Materials and methods

Virus and cells

African green monkey kidney fibroblasts (Vero cells, ATCC CCL-81, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were propagated in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, gentamicin, and antimycotic-antibiotic solution (complete medium, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at 37°, 5% CO2 and 95% humidity. HSV-2 (clinical isolate obtained from Louisiana State University Hospital, New Orleans, LA) was propagated in Vero cells. Stocks were stored at −80° of 4 × 106 plaque-forming units (PFU)/ml and diluted in complete medium immediately before use.

Mice

Female wild-type C57BL/6 mice (The Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME), which are deficient in the downstream effector molecule (RNase L) following activation of oligoadenylate synthetases (RL–/–),13 mice deficient in PKR (PKR–/–)14 and mice deficient in both RNase L and PKR (PKR/RL–/–)15 (8–12 weeks of age) were injected with 2 mg of DepoProvera (Pharmacia and Upjohn Co., Kalamazoo, MI) subcutaneously to augment susceptibility to genital HSV-2 infection.16 Following a 5-day incubation period, the mice were intravaginally challenged with HSV-2 (2000 PFU). Mice were killed at various times post infection to determine the virus titre, for phenotypic analysis of the inguinal/iliac lymph nodes, spinal cord and brainstem, and to measure cytokine/chemokine content. Alternatively, mice were monitored and their survival was recorded over 30 days. All procedures were approved by The University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center and Dean A. McGee Eye Institute animal care and use committee.

Virus plaque assay

Clarified supernatant from homogenized tissue or vaginal lavages was serially diluted and added to Vero cell monolayers in 96-well cultured plates in a volume of 100 μl. After a 1-hr incubation period at 37° in 95% humidity and 5% CO2, the supernatant was removed and 100 μl of overlay solution (0·5% methylcellulose in complete medium) was added on top of the monolayer. The cultures were incubated for an additional 30 hr under the same conditions and subsequently scored for plaque formation.

Spinal cord and brainstem cell suspensions

Mice were anaesthetized and perfused at day 7 post-infection (pi) and the spinal cord and brainstem were removed and subjected to homogenization on ice using a Dounce homogenizer (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Following homogenization, the samples were passed through a 70-μm cell strainer (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA), flushed with 5 ml RPMI-1640, centrifuged (300 g, 5 min) and resuspended in 4·0 ml phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH = 7·4) containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Samples were subsequently prepared for flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions from inguinal/iliac lymph nodes were generated by forcing the lymph nodes through a cell strainer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) in complete medium. The cells were counted and 1 × 106 cells were added to 5 ml polystyrene round-bottomed tubes (Becton Dickinson). The cells were washed and resuspended in 100 μl PBS containing 1% BSA. Four microlitres of anti-mouse CD16/CD32 (FcγIII/II receptor) (2.4G2) (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) was added to the cells to prevent non-specific binding of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated monoclonal antibodies. Following a 20-min incubation period on ice, the cells were washed with 1·0 ml PBS/1% BSA and resuspended in 100 μl PBS/1% BSA in which 4 μl phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-mouse CD3 (BD Pharmingen) and either 4 μl FITC-conjugated anti-mouse CD4 (BD Pharmingen) or anti-mouse CD8 (BD Pharmingen) was added. Alternatively, FITC-conjugated anti-mouse CD8 (BD Pharmingen) along with PE-labelled MHC pentamer representing the major HSV-1 epitope from glycoprotein B498−505 (gB; H-2Kb peptide SSIEFARL, Proimmune, Oxford, UK) was added to identify HSV-2 gB-specific CD8+ T cells. Upon labelling the cells with the pairs of antibodies, the cells were incubated for 20–30 min on ice in the dark. After the incubation period, the cells were washed twice in 1·0 ml PBS/1% BSA and resuspended in PBS containing 1% paraformaldehyde. For spinal cord and brainstem sample T-cell content, 4 μl anti-mouse CD16/CD32 (FcγIII/II receptor) (2.4G2) (BD Pharmingen) was added to the cells to prevent non-specific binding of FITC-conjugated monoclonal antibodies. Following a 20-min incubation period on ice, the cells were washed with 1·0 ml PBS/1% BSA and resuspended in 100 μl PBS/1% BSA in which single-cell suspensions were triple-labelled with PE-conjugated anti-CD3, FITC-conjugated anti-CD4 or anti-CD8, and PE-Cy5-conjugated anti-CD45 (clone 30-F11, BD Pharmingen). The cells were incubated, washed, fixed and resuspended as indicated above. Before analysis, 30 μl of a solution of CountBright absolute counting beads (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) was added to each sample. Cells from the lymph nodes, spinal cord and brainstem were analysed on a Coulter Epics XL flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL) and the data were analysed using expo 32 adc software (Beckman Coulter). The spinal cord and brainstem cell suspensions were gated on CD45-expressing cells, and the percentages of CD4 and CD8 T cells were determined under this gate setting. Samples were analysed for 1100 seconds with the absolute number of leucocytes (CD45high) contained within the tissue determined by the number of events within the established gate normalized to the reference bead count/sample multiplied by the dilution factor (4·5 for the spinal cord and 9·0 for the brainstem). Isotypic control antibodies were included in the analysis to establish background fluorescence levels.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

The detection of IFN-γ within the infected vagina, spinal cord and brainstem was performed using a commercially available kit (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The sensitivity of the assay was 10 pg/tissue. Each sample was assayed in duplicate along with a standard that was provided in the kit and used to determine the unknown amount for each sample. Standard curves did not fall below a correlation coefficient of 0·9920. The amount of IFN-γ measured was normalized to the total wet weight of each tissue under study and is expressed as pg/g ± SEM for each tissue. The detection of CC chemokine ligand-2 (CCL2), CCL3, CCL5, CXC chemokine ligand-1 (CXCL1), IL-1β, IL-6, tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and IFN-γ expressed in the inguinal/iliac lymph nodes was performed using a suspension array system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) with a sensitivity of 1–2 pg/tissue for each targeted analyte. Each sample was analysed in duplicate along with known amounts of cytokine/chemokine as provided by the kits to generate a standard curve which was then used to determine the quantity of each cytokine/chemokine in a given sample.

Statistics

One-way analysis of variance (anova) and Tukey's post-hoc t-test were used to determine significance of differences (i.e. P < 0·05) between the wild-type and gene knockout mice with the exception of the cumulative survival studies. In that instance, the Mann–Whitney rank order test was performed comparing the wild-type mice to each of the other groups of animals at each time-point over the course of 30 days. All statistical analysis was performed using the gbstat program (Dynamic Microsystems, Silver Springs, MD).

Results

The absence of PKR but not RL enhances susceptibility to genital HSV-2 infection

Wild-type mice were compared to RL–/–, PKR–/– and PKR/RL–/– mice for sensitivity to genital HSV-2 infection. The absence of either PKR alone or PKR and RL rendered mice highly susceptible to HSV-2 infection with a reduction in cumulative survival (Fig. 1). In contrast, RL–/– mice had survival similar to that of the wild-type control animals (Fig. 1). Next, virus titres measuring the amount of virus shed as well as the amount found in the infected tissue were conducted. Viral titres were elevated in the spinal cord of the PKR/RL–/– mice compared with wild-type animals (Fig. 1). However, RL–/– mice possessed significantly less virus in the spinal cord in comparison to any of the other groups of infected animals (Fig. 1). There were no other differences between RL–/– to wild-type mouse virus titres in the brainstem. However, both PKR–/– and PKR/RL–/– mice had significantly higher levels of HSV-1 in the brainstem in comparison to wild-type or RL–/– mice (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1.

PKR–/– and PKR/RL–/– mice are highly sensitive to genital HSV-2 infection. (a) Mice (n = 15–32/group) were treated with DePoProvera and subsequently infected with HSV-2 (2000 pfu/vagina) 5 days later. The mice were monitored for survival over 30 days and results were recorded. The data are representative of three to five experiments/group. *P < 0·05 comparing the PKR–/– or the PKR/RL–/– to the wild-type (WT) controls. (b) Mice were treated and infected as described in (a). The animals were killed 7 days post infection. The indicated tissue was collected and processed for HSV-2 titres as determined by plaque assay. The results are a representative experiment from two to four experiments/group, n = 4 samples/experiment. Bars represent the mean ± SEM. *P < 0·05 comparing the RL–/–, PKR–/–, and PKR/RL–/– to the wild-type samples for each respective tissue; †P < 0·05 comparing the RL–/– to the PKR–/– and PKR/RL–/– brainstem samples.

PKR/RL–/– mice show a reduction in CD3+ CD8+ T cells in the draining lymph node but enhanced trafficking in the central nervous system

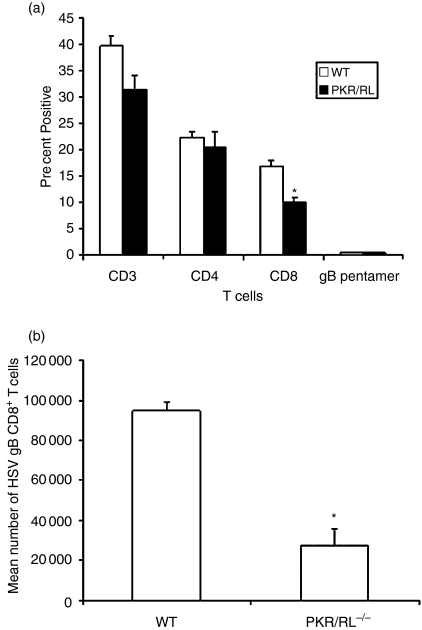

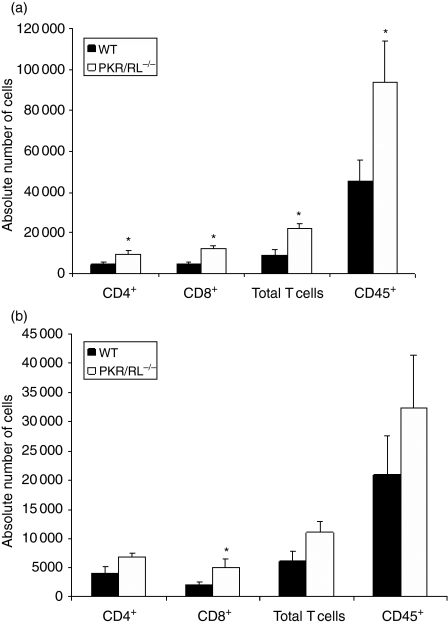

Previous studies have implicated T cells in the resistance to genital HSV-2 infection using T-cell-depleted mice or adoptive transfer experiments using inguinal/iliac lymph node syngeneic T cells from HSV-2 vaccinated animals.17,18 Therefore, T cells were evaluated in the draining lymph nodes following HSV-2 infection. At this point, the study focused on the PKR/RL–/– mice as this group exhibited the greatest sensitivity to genital HSV-2 infection based on cumulative survival and virus titres. Whereas there was no difference in the total number of cells recovered in the draining lymph nodes of the HSV-2-infected wild-type (8·1 ± 0·36 × 106 cells) versus PKR/RL–/– (6·3 ± 1·6 × 106 cells) mice, the percentage of CD8+ but not CD4+ T cells was reduced in the lymph node of the PKR/RL–/– animals (Fig. 2). Nearly equivalent percentages of HSV-specific CD8+ T cells were found in each population of draining lymph node lymphocytes. However, taking into account the absolute number of cells recovered in the nodes and the percentage that were CD8+ T cells, there was a striking difference in the number of HSV gB-specific CD8+ T cells with nearly three-fold more found in the inguinal/iliac lymph nodes of the wild-type mice than in the PKR/RL–/– animals (Fig. 2). Next, T-cell infiltration was assessed in the infected tissue of PKR/RL–/– and wild-type mice. The results show significantly greater numbers of CD8+ T cells residing in the spinal cord and brainstem of the PKR/RL–/– mice compared to the wild-type controls in response to genital HSV-2 infection (Fig. 3). In addition, the spinal cord contained significantly more CD4+ and total T cells and CD45+ leucocytes (Fig. 3). In contrast, HSV-2-infected RL–/– mice showed similar levels of CD4+, CD8+, total T cells, and CD45+ leucocytes in the spinal cord and brainstem relative to HSV-2-infected wild-type animals (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Reduction in CD8+ T cells residing in the draining lymph nodes from PKR/RL–/– mice following genital HSV-2 infection. Mice were treated as described in Fig. 1(a). Seven days post infection, the inguinal/iliac lymph nodes were removed from wild-type (WT) and PKR/RL–/– mice, counted, and phenotypically characterized for T-cell populations as well as HSV gB-specific CD8+ T cells by flow cytometry. (a) Results expressed as mean percentage ± SEM for total T cells (CD3), CD4 T cells (CD3+ CD4+), CD8 T cells (CD3+ CD8+), and CD8 gB pentamer positive (CD8+ gB498−505+) T cells. Bars represent mean ± SEM, n = 6–9/group from two experiments. (b) To determine the number of HSV gB-specific CD8+ T cells, the percentage of gB pentamer CD8+ T cells in the total CD8+ T-cell population was determined in the draining lymph nodes 7 days post infection and multiplied by the number of cells recovered from each lymph node sample. The bars represent the mean number of gB-specific CD8+ T cells ± SEM. *P < 0·05 comparing the PKR/RL–/– to wild-type control.

Figure 3.

Elevation in the number of CD8+ T cells infiltrating the spinal cord and brainstem of PKR/RL–/– mice. Mice were treated as described in Fig. 1(a). Seven days post infection, the spinal cord (a) and brainstem (b) were removed from the wild type (WT) and PKR/RL–/– mice processed and phenotypically characterized for T cells by flow cytometry. Each sample was spiked with 1500 Countbright™ beads that were simultaneously gated in a separate channel from the CD45+ gated cells. The results for each sample are presented as absolute number of cells for each group analysed. Bars represent mean number of cells ± SEM, n = 5–7/group summarizing two experiments. *P < 0·05 comparing the PKR/RL–/– to WT mice.

CCL3, IFN-γ and TNF-α levels are elevated in PKR/RL–/– mouse draining lymph node

IFN-γ is associated with protection against genital HSV-2 infection on multiple levels including facilitating the recruitment of effector lymphocytes, development of Th1 cells, enhanced NK cell activity, and direct antiviral action.19–22 Therefore, IFN-γ levels were measured in the genital tissue and nervous system comparing the wild-type to PKR/RL–/– mice. Both groups of mice possessed similar levels of IFN-γ in all tissues investigated (data not shown). Relative to the draining lymph nodes, PKR/RL–/– mouse inguinal/iliac lymph nodes contained elevated levels of IFN-γ in comparison to RL–/– or wild-type tissue (Table 1). Furthermore, PKR/RL–/– mouse inguinal/iliac lymph nodes also contained higher levels of CCL3 and TNF-α in comparison to either the RL–/– or wild-type lymph nodes. No other cytokines or chemokines tested, including IL-1β, IL-6, CXCL1, CCL2, or CCL5, were found to be different between the PKR/RL–/– and the wild-type mice (data not shown).

Table 1.

Cytokine/chemokine levels in inguinal/iliac lymph nodes of HSV-2-infected mice1

| Mice | IFN-γ | TNF-α | CCL3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | 2·5 ± 0·2 | 2·8 ± 0·5 | 21·8 ± 1·3 |

| RL–/– | 2·6 ± 0·2 | 2·1 ± 1·0 | 24·3 ± 3·8 |

| PKR/RL–/– | 5·2 ± 0·3** | 6·9 ± 1·5** | 40·8 ± 3·6** |

C57BL/6 (wild-type) mice, mice deficient in RNase L (RL–/–), or mice deficient in both RNase L and PKR (PKR/RL–/–) (three or four mice per experiment) were infected with HSV-2 (2000 PFU/vagina) and killed 7 days post-infection. The inguinal/iliac lymph nodes were removed and processed for the detection of cytokines/chemokines using a suspension array detection system. Numbers represent the mean ± SEM in pg/lymph node summarizing the results from two experiments.

P < 0·05, comparing the gene-deficient mice with the wild-type controls as determined by anova and Tukey's t-test.

Discussion

The activation of OAS and PKR pathways by type I IFNs often results in an increase in resistance to virus infection.23,24 Relative to OAS, 2′,5′-oligoadenylate trimers have been reported to be effective against genital HSV-2 infection in guinea-pigs.25 In the present study, mice deficient in a functional OAS pathway showed no difference in susceptibility to genital HSV-2 infection as measured by survival over 30 days. However, the results measuring virus load in the infected tissues were less clear comparing the RL–/– to wild-type mice with a decrease in virus titre in the spinal cord of the RL–/– mice. Currently, we have no explanation for this finding because similar levels of HSV-2 were found at the site of initial infection (vagina) and at the end-point of the acute infection within the brain (i.e. brainstem) of wild-type and RL–/– mice. In contrast, mice deficient in either PKR alone or a functional PKR and OAS pathway were found to be highly sensitive to HSV-2 infection based on virus titres recovered in the infected vaginal tissue and brainstem and on cumulative survival. The virus titre in the brainstem was highly correlated with the mortality results, suggesting that this tissue is a good predictor of the outcome of infection. Other studies have also found higher titres of HSV-2 in the central nervous system of mice with lower survival rates consistent with the neurotropism of the virus.8,10,18,26 Unlike the present results using PKR–/– mice, another group reported no difference in sensitivity to genital HSV-2 infection in PKR–/–mice.10 We have previously reported the absolute requirement for PKR expression in IFN-α1 resistance to genital HSV-2 infection.27 The discrepancy of our results to those previously reported may reside with the difference in the strain of PKR–/– mouse employed (C57BL/6 versus B6/129) or virus strain and inoculum. The present study used a virus inoculum of 2000 PFU of a clinical HSV-2 isolate. The study by Murphy and colleagues used a laboratory strain of HSV-2 (strain 333) at an infectious dose of 2 × 106 PFU. Since we have previously reported that the differences between PKR–/– and wild-type cells are dose-dependent28 it is possible that the infectious dose used by Murphy and colleagues may be too high to discern changes in sensitivity between the response of PKR–/– and wild-type mice to genital HSV-2 infection.

Cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) are components of the adaptive immune response that are implicated in the control of HSV-2 replication.29 HIV-infected individuals presenting with more severe genital herpes recurrences have a lower percentage of CD8+ precursor CTLs than individuals with less severe recurrences.30 Since HSV-1 gB and HSV-2 gB share a high degree of homology at the amino acid level31 and HSV gB has successfully been used to vaccinate rodents32 (generating CTLs that recognize and protect the animals against a subsequent genital HSV-2 infection33), we investigated the occurrence of gB-specific CTLs in the draining lymph nodes of the HSV-2-infected mice. Based on the results showing a three-fold increase in the number of HSV gB-specific CD8+ T cells in the wild-type compared to PKR/RL–/– mice, it is tempting to speculate that the difference in sensitivity to genital HSV-2 infection may be the result of the frequency of these cells. However, given that frequent recurrence of genital herpes can occur even in the presence of circulating CTLs,34 other factors in addition to CTLs are likely to be involved in the control of virus replication and spread.

IFN-γ is another immune component found to be critical in controlling genital HSV-2 infection both locally4,19,20 and within the central nervous system.35 Along these lines, we found no difference in the level of IFN-γ within the vagina, spinal cord, or brainstem of HSV-2-infected wild-type or PKR/RL–/– mice. However, there was an increase in IFN-γ content within the draining lymph nodes of the PKR/RL–/– mice. There was also an increase in the expression of TNF-α and CCL3 in the inguinal/iliac lymph nodes from the HSV-2-infected PKR/RL–/– mice. The increase in expression of these cytokines and chemokine mirrors the virus load in the vaginal tissue and brainstem of the PKR/RL–/– mice, suggesting that the increase in antigen available may drive the elevated expression. In contrast to the increase in TNF-α and IFN-γ expression, the percentage of CD8+ T cells and the absolute number of HSV gB-specific CD8+ T effector cells was found to be reduced within the regional lymph nodes of the PKR/RL–/– mice. In a reciprocal fashion, there were more CD8+ T cells residing in the spinal cord and brainstem of HSV-2-infected PKR/RL–/– mice. The T cells may be drawn to the central nervous system as a result of enhanced virus found in the tissue. As a result of the low number of cells recovered from the tissue, it is currently difficult to assess the function of these cells. However, it is intriguing to note that PKR alone is a negative regulator of CD8+ T-cell function as measured by changes in the magnitude of contact hypersensitivity.36 Collectively, these results demonstrate that the expression of PKR is a necessary component of the host response to genital HSV-2 infection in preventing virus replication and spread, as shown by the increased susceptibility of mice deficient in PKR to the virus.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by USPHS grants AI053108 (D.J.J.C), AI34039 (B.R.G.W), CA44059 (R.H.S), and NEI core grant EY12190.

Abbreviations

- anova

analysis of variance

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CCL

CC chemokine ligand

- CXCL

CXC chemokine ligand

- CTL

cytotoxic T lymphocyte

- gB

glycoprotein B

- HSV-2

herpes simplex virus type 2

- IFN

interferon

- IL

interleukin

- NK

natural killer

- OAS

oligoadenylate synthetases

- PFU

plaque-forming units

- pg

picogram

- pi

post-infection

- PKR

RNA-dependent protein kinase

- RL

RNase L

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- TNF

tumour necrosis factor

References

- 1.Armstrong GL, Schillinger J, Markowitz L, Nahmias AJ, Johnson RE, McQuillan GM, St Louis ME. Incidence of herpes simplex virus type 2 in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153:912–20. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.9.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lafferty W, Coombs RW, Benedetti J, Critchlow C, Corey L. Recurrences after oral and genital herpes simplex virus infections. Influence of site of infection and viral type. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1444–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198706043162304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milligan GN. Neutrophils aid in protection of the vaginal mucosae of immune mice against challenge with herpes simplex virus type 2. J Virol. 1999;73:6380–6. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6380-6386.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harandi AM, Svennerholm B, Holmgren J, Eriksson K. Differential roles of B cells and IFN-γ-secreting CD4+ T cells in innate and adaptive immune control of genital herpes simplex virus type 2 infection in mice. J Gen Virol. 2001;82:845–53. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-4-845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ashkar AA, Rosenthal KL. Interleukin-15 and natural killer and NKT cells play a critical role in innate protection against genital herpes simplex virus type 2 infection. J Virol. 2003;77:10168–71. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.18.10168-10171.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gill N, Rosenthal KL, Ashkar AA. NK and NKT cell-independent contribution of interleukin-15 to innate protection against mucosal viral infection. J Virol. 2005;79:4470–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.7.4470-4478.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lund J, Sato A, Akira S, Medzhitov R, Iwasaki A. Toll-like receptor 9-mediated recognition of herpes simplex virus-2 by plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2003;198:513–20. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Härle P, Noisakran S, Carr DJJ. The application of a plasmid DNA encoding IFN-α1 enhances cumulative survival of herpes simplex virus type 2 vaginally infected mice. J Immunol. 2001;166:1803–12. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill AB, Barnett BC, McMichael AJ, McGeoch DJ. HLA class I molecules are not transported to the cell surface in cells infected with herpes simplex virus type 1 and 2. J Immunol. 1994;152:2736–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy JA, Duerst RJ, Smith TJ, Morrison LA. Herpes simplex virus type 2 virion host shutoff protein regulates alpha/beta interferon but not adaptive immune responses during primary infection in vivo. J Virol. 2003;77:9337–45. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.17.9337-9345.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Härle P, Cull V, Guo L, Papin J, Lawson C, Carr DJJ. Transient transfection of mouse fibroblasts with type I interferon transgenes provides various degrees of protection against herpes simplex virus infection. Antiviral Res. 2002;56:39–49. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(02)00093-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duerst RJ, Morrison LA. Herpes simplex virus 2 virion host shutoff protein interferes with type I interferon production and responsiveness. Virology. 2004;322:158–67. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou A, Paranjape J, Brown TL, et al. Interferon action and apoptosis are defective in mice devoid of 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthetase-dependent RNase L. EMBO J. 1997;16:6355–63. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.21.6355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang YL, Reis LF, Pavlovic J, et al. Deficient signaling in mice devoid of double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase. EMBO J. 1995;14:6095–106. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00300.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou A, Der Paranjape JMSD, Williams BRG, Silverman RH. Interferon action in triply deficient mice reveals the existence of alternative antiviral pathways. Virology. 1999;258:435–40. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaushic C, Ashkar AA, Reid LA, Rosenthal KL. Progesterone increases susceptibility and decreases immune responses to genital herpes infection. J Virol. 2003;77:4558–65. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.8.4558-4565.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDermott MR, Goldsmith CH, Rosenthal KL, Brais LJ. T lymphocytes in genital lymph nodes protect mice from intravaginal infection with herpes simplex virus type 2. J Infect Dis. 1989;159:460–6. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.3.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dudley KL, Bourne N, Milligan GN. Immune protection against HSV-2 in B-cell-deficient mice. Virology. 2000;270:454–63. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milligan GN, Bernstein DI. Interferon-γ enhances resolution of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection of the murine genital tract. Virology. 1997;229:259–68. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parr MB, Parr EL. The role of gamma interferon in immune resistance to vaginal infection by herpes simplex virus type 2 in mice. Virology. 1999;258:282–94. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parr MB, Parr EL. Interferon-γ up-regulates intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 and recruits lymphocytes into the vagina of immune mice challenged with herpes simplex virus-2. Immunol. 2000;99:540–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00980.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Svensson A, Nordström I, Sun J-B, Eriksson K. Protective immunity to genital herpes simplex virus type 2 infection is mediated by T-bet. J Immunol. 2005;174:6266–73. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hassel BA, Zhou A, Sotomayor C, Maran A, Silverman RH. A dominant negative mutant of 2–5A-dependent Rnase suppresses antiproliferative and antiviral effects of interferon. EMBO J. 1993;12:3297–304. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05999.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Der SD, Lau AS. Involvement of the double-stranded RNA-dependent kinase PKR in interferon expression and interferon-mediated antiviral activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8841–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujihara M, Milligan JR, Kaji A. Effect of 2′,5′-oligoadenylate on herpes simplex virus-infected cells and preventive action of 2′,5′-oligoadenylate on the lethal effect of HSV-2. J Interferon Res. 1989;9:691–707. doi: 10.1089/jir.1989.9.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDermott MR, Smiley JR, Leslie P, Brais J, Rudzroga HE, Bienenstock J. Immunity in the female genital tract after intravaginal vaccination of mice with an attenuated strain of herpes simplex virus type 2. J Virol. 1984;51:747–53. doi: 10.1128/jvi.51.3.747-753.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carr DJJ, Tomanek L, Silverman RH, Campbell IL, Williams BRG. RNA-dependent protein kinase is required for alpha-1 interferon transgene-induced resistance to genital herpes simplex virus type 2. J Virol. 2005;79:9341–5. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.14.9341-9345.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-khatib K, Williams BRG, Silverman RH, Halford W, Carr DJJ. The murine double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase PKR and the murine 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthetase-dependent RNase L are required for IFN-β-mediated resistance against herpes simplex virus type 1 in primary trigeminal ganglion culture. Virology. 2003;31:126–35. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00298-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Posavad CM, Koelle DM, Corey L. High frequency of CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocyte precursors specific for herpes simplex viruses in persons with genital herpes. J Virol. 1996;70:8165–8. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.8165-8168.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Posavad CM, Koelle DM, Shaughnessy MF, Corey L. Severe genital herpes infections in HIV-infected individuals with impaired herpes simplex virus-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10289–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stuve LL, Brown-Shimer S, Pachl C, Najarian R, Dina D, Burke RL. Structure and expression of the herpes simplex virus type 2 glycoprotein gB gene. J Virol. 1987;61:326–35. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.2.326-335.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stanberry LR, Bernstein DI, Burke RL, Pachl C, Myers MG. Vaccination with recombinant herpes simplex virus glycoproteins: protection against initial and recurrent genital herpes. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:914–20. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.5.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gallichan WS, Woolstencroft RN, Guarasci T, McCluskie MJ, Davis HL, Rosenthal KL. Intranasal immunization with CpG oligodeoxynucleotides as an adjuvant dramatically increases IgA and protection against herpes simplex virus-2 in the genital tract. J Immunol. 2001;166:3451–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.5.3451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Posavad CM, Huang ML, Barcy S, Koelle DM, Corey L. Long term persistence of herpes simplex virus-specific CD8+ CTL in persons with frequently recurring genital herpes. J Immunol. 2000;165:1146–52. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewandowski G, Hobbs M, Geller A. Evidence that deficient IFN-γ production is a biological basis of herpes simplex virus type-2 neurovirulence. J Neuroimmunol. 1998;81:66–75. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(97)00160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kadereit S, Xu H, Engeman TM, Yang Y-L, Fairchild RL, Williams BRG. Negative regulation of CD8+ T cell function by the IFN-induced and double-stranded RNA-activated kinase PKR. J Immunol. 2000;165:6896–901. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.6896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]