Abstract

Circulating Vγ2Vδ2 T-cell populations in healthy human beings are poised for rapid responses to bacterial or viral pathogens. We asked whether Vγ2Vδ2 T cells use the Toll-like receptor (TLR) family to recognize pathogen-associated molecular pattern molecules and to regulate cell functions. Analysis of expanded Vγ2Vδ2 T-cell lines showed the abundant presence of TLR2 mRNA, implying that these receptors are important for cell differentiation or function. However, multiple efforts to detect TLR2 protein on the cell surface or in cytoplasmic compartments gave inconsistent results. Functional assays confirmed that human Vγ2Vδ2 T cells could respond to the TLR2 agonist (S)-(2,3-bis(palmitoyloxy)-(2RS)-propyl)-N-palmitoyl-(R)-Cys-(S)-Ser(S)-Lys4-OH trihydrochloride (Pam3Cys), but the response required coincident stimulation through the γδ T-cell receptor (TCR). Dually stimulated cells produced higher levels of cytoplasmic or cell-free gamma interferon and showed increased expression of the lysosome-associated membrane protein CD107a on the cell surface. A functional TLR2 that requires coincident TCR stimulation may increase the initial potency of Vγ2Vδ2 T-cell responses at the site of infection and promote the rapid development of subsequent acquired antipathogen immunity.

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) expressing the Vγ2Vδ2 T-cell receptor (TCR) comprise about 5% of CD3+ cells and are the major subset of circulating Vγ2Vδ2 T cells in human (10, 13, 24) and nonhuman (27) primates. Within this population in healthy adult human beings, around 75% have the Vγ 2-Jγ 1.2 rearrangement (15). This unusual population arises by chronic, positive selection in the periphery (10, 13) and becomes established by 2 years of age in human beings (14).

The mechanisms for antigen recognition by Vγ2Vδ2 T cells are controversial. Circulating γδ cells in PBMC generate in vitro TCR-dependent (7, 23) proliferative responses to naturally occurring low-molecular-weight compounds, including alkylphosphates and alkylamines (16, 32). Similar compounds are elevated in plasma during bacterial infection (8) and might provide a generic signal to activate T-cell immunity. However, these same Vγ2Vδ2 T cells also recognize some tumors and cells infected by bacteria or viruses (3-5, 19, 26, 28, 33) in a species-specific manner (20), arguing that recognition requires antigen presentation or other cell surface interactions. Since Vγ2Vδ2 T-cell recognition of low-molecular-weight compounds or cells is major histocompatibility complex unrestricted, we presume that any presenting molecules would be nonpolymorphic (7, 12, 23, 30). At present, the molecular details of Vγ2Vδ2 TCR recognition of antigen are unclear, and the roles of other ligands in controlling these responses are also unknown.

Recognizing that Vγ2Vδ2 T cells display broad recognition of bacteria and infected cells, we asked whether pathogen-associated molecular pattern molecules might also be involved in these responses. For example, gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor alpha were produced by human Vγ2Vδ2 T cells as early as 2 h after exposure to live but not dead bacteria or lipopolysaccharides (LPS); these cytokines were expressed in an on/off/on cycling pattern and regulated monocyte killing of Escherichia coli (34). The response to LPS implies the presence of functional Toll-like receptors (TLR). The TLR are signal-transducing molecules that recognize specific microbial pathogen-associated molecular patterns and are expressed in a variety of cell types, including dendritic cells, macrophages, and lymphocytes (22, 25). TLR2 in particular is a signal-transducing molecule for LPS from nonenterobacterial gram-negative organisms (18, 35). Other bacterial lipoproteins (1) and the synthetic lipoprotein (S)-(2,3-bis(palmitoyloxy)-(2RS)-propyl)-N-palmitoyl-(R)-Cys-(S)-Ser(S)-Lys4-OH trihydrochloride (Pam3Cys) (1, 2) also signal through TLR2. Efforts to detect TLR2 on αβ T cells showed that the protein was present at very low levels and that a subset of CD4+ CD45RO+ memory cells expressed TLR2 and responded to a specific TLR2 receptor agonist with enhanced IFN-γ production (21). Heat shock protein 60 may also signal through TLR2 to promote SOCS3 and STAT3 activation, increase β1 integrin expression in human αβ T cells, and enhance T-cell binding to fibronectin (37).

We wondered about the possible role for TLR2 signaling in Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. It is important to note that the majority of circulating Vγ2Vδ2 T cells have a memory phenotype and generate memory-type responses to in vitro stimulation (14). This property reflects the peripheral selection mechanisms that shaped the mature Vγ2Vδ2 TCR repertoire (10, 13), resulting in a large, circulating memory T-cell subset with the capacity for rapid responses to a variety of bacterial or viral infections. Here we report that TLR2 was difficult to detect on the surface of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells but that these cells were functionally responsive to the TLR2 agonist Pam3Cys. We show that TLR2 signaling specifically increases IFN-γ release in Vγ2Vδ2 T cells but requires concomitant TCR stimulation for this effect. The response is rapid compared to other systems. The presence of a functional TLR2 receptor on Vγ2Vδ2 T cells further supports a role for this T-cell subset in early responses to infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture of Vγ2Vδ2 cell lines.

Whole blood was obtained with informed consent from six healthy, human volunteers, and research protocols were reviewed by the Institutional Human Subject Review Committee (University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD). Total lymphocytes were separated from heparinized peripheral blood by density gradient centrifugation (Ficoll-Paque; Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). PBMC were frozen at 1 × 106 to 10 × 106 cells/ml in fetal bovine serum (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY) with 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and stored at −130°C. PBMC were thawed and cultured in RPMI 1640 (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY), and penicillin (100 U/ml)-streptomycin (100 μg/ml) (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY). PBMC were stimulated by a single addition of isopentyl pyrophosphate (IPP) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at a final concentration of 15 μM with 100 U/ml human recombinant interleukin-2 (IL-2) (Tecin, Biological Resources Branch, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Fresh medium including 100 U/ml IL-2 was added every 3 days, and PBMC were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 14 days to generate Vγ2Vδ2 cell lines. At day 14, Vγ2Vδ2 T cells comprised greater than 74% of CD3+ cells in these cultures. Vγ2Vδ2 cell lines were stored at −130°C.

For stimulation prior to staining or supernatant collection, Vδ2 T-cell lines were cultured in 96-well plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY) at 2 × 105 cells/well in 200 μl in the presence of 10 U/ml IL-2. In some experiments, wells were coated with the anti-human γδ TCR antibody clone B1.1 (eBiosciences, San Diego, CA) and the synthetic lipoprotein Pam3Cys-SK4 (Pam3Cys; EMC, Tuebingen, Germany) was added at a concentration of 10 μg/ml. Some cells were stimulated with phytohemagglutinin (PHA) (Remel, Lenexa, KS) at a concentration of 10 μg/ml, IPP at 15 μM, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at 10 ng/ml, and ionomycin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at 1 μg/ml.

Detection of TLR2 mRNA in Vγ2Vδ2 T cells.

Total RNA was extracted from cells by using the RNeasy minikit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) as described by the manufacturer. One microgram of total RNA was then converted into cDNA by using a reverse transcription system kit (Promega, Madison, WI) in a reaction mixture containing 500 ng of oligonucleotide A (T15V),1 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), 50 mM KCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 18 units of avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase, and 10 units of RNasin RNase inhibitor. Each reaction mixture was incubated at 42°C for 2 h, and then cDNA was diluted to 100 μl by adding 80 μl of deionized H2O to the mixture. PCR was performed using 5 μl cDNA as the template and then adding 500 nM each of forward and reverse primers (IDT, Coralville, IA), 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (Promega, Madison, WI), 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), 50 mM KCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 1 unit of AmpliTaq Gold (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The following primers were used: 5′ TLR1 (5′-ATCGTCACCATCGTTGCCAC-3′) and 3′ TLR1 (5′-CTGGACAAAGTTGGGAGACAAAA-3′), 5′ TLR2 (5′-GCTCTGGTGCTGACATCCAATG-3′) and 3′ TLR2 (5′-GCATCAATCTCAAGTTCCTCAAGG-3′), 5′ TLR3 (5′-TGGCTAAAATGTTTGGAGCACC-3′) and 3′ TLR3 (5′-TCAGTCGTTGAAGGCTTGGGAC-3′), 5′ TLR4 (5′-TGATGCCAGGATGATGTCTGC-3′) and 3′ TLR4 (5′-TGTAGAACCCGCAAGTCTTGTGC-3′), 5′ TLR5 (5′-CGGGTTTGGCTTCCATAACATC-3′) and 3′ TLR5 (5′-GGTTGTAAGAGCATTGTCTCGGAG-3′), 5′ TLR6 (5′-TCTTGGGATTGAGTGCTATGAAGC-3′) and 3′ TLR6 (5′-AAGTCGTTTCTATGTGGTTGAGGG-3′), 5′ TLR7 (5′-ACAGATGTGACTTGTGTGGGGC-3′) and 3′ TLR7 (5′-TTCTCTCTTGGGTCTTCCAGTTTG-3′), 5′ TLR8 (5′-ACAGCACCAGAACGGAAATCC-3′) and 3′ TLR8 (5′-CAGAAAAAGTTTGCGTAGGGAGC-3′), 5′ TLR9 (5′-TCACCAGCCTTTCCTTGTCCTC-3′) and 3′ TLR9 (5′-AGTTTGACGATGCGGTTGTAGG-3′), 5′ TLR10 (5′-GGATGCTAGGTCAATGCACA-3′) and 3′ TLR10 (5′-ATAGCAGCTCGAAGGTTTGC-3′), and 5′ β-actin (5′-GTGGGGCGCCCCAGGCACCA-3′) and 3′ β-actin (5′-CTCCTTAATGTCACGCACGATTTC-3′). The PCR profile was as follows: denaturation for 1 min at 94°C; 5 min at 68°C; 45 cycles of 45 seconds at 94°C, 1 min at 60°C, and 1 min at 72°C; and extension for 10 min at 72°C. PCR products were separated on 1.5% agarose-Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer gels (Fisher, Fair Lawn, NJ) containing 0.5 μg/ml ethidium bromide (Sigma, St. Louis, MO).

Detection of cytokines by ELISA.

Human IFN-γ in culture supernatants was detected with a human IFN-γ enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer's directions. Human RANTES in culture supernatants was detected with a human RANTES ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer's directions.

Flow cytometry.

Expanded Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were stained for cell surface markers with fluorophore-conjugated monoclonal antibodies. All antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA) unless otherwise noted. Generally, 3 × 105 cells were washed, resuspended in 50 to 100 μl of RPMI 1640, and stained with the following antibodies: mouse anti-human Vδ2-phycoerythrin (PE) clone B6, mouse anti-human CD3-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) clone UCHT1, mouse anti-human TLR2-FITC clone TL2.1 (eBiosciences, San Diego, CA) (sodium azide was removed from antibody solutions by a 16-hour dialysis in phosphate-buffered saline to reduce cellular toxicity when staining at 37°C), mouse anti-human IFN-γ-FITC clone B27, mouse anti-human CD107a-FITC clone H4A3, and isotype controls, including rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1)-FITC clone X40, IgG1-PE clone X40 and IgG2a-FITC clone X39. After 20 min at 4°C (1 h at 37°C for TLR2-FITC), cells were washed and resuspended in RPMI 1640 containing 2% paraformaldehyde. To stain for intracellular IFN-γ, expanded cells were first stained with Vδ2-PE and then fixed and permeabilized prior to a 45-min incubation at 4°C with anti-IFN-γ conjugated to FITC. Intracellular staining solutions were obtained in a Cytofix/Cytoperm Kit (BD, San Diego, CA). At least 104 lymphocytes (gated on the basis of forward- and side-scatter profiles) were acquired for each sample on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD, San Diego, CA). All samples were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, San Carlos, CA).

Statistical analysis.

Differences among groups (more than two) were analyzed by Student's t test. P values of ≤0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

TLR2 mRNA is present in expanded Vγ2Vδ2 T cells.

PBMC were purified from healthy adult volunteers and stained for CD3 and Vδ2. There was normal variation in the frequency of Vγ2Vδ2 cells among healthy donors, ranging from 3 to 32% of total CD3+ cells. Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were expanded after IPP treatment and 14 days of culture with a high IL-2 concentration (100 U/ml). The frequency of Vγ2Vδ2 cells after expansion varied from 74 to 97% of CD3+ cells. Following expansion, cells were rested in a low concentration of IL-2 (10 U/ml) and then stained for flow cytometry or used for RNA and protein analysis.

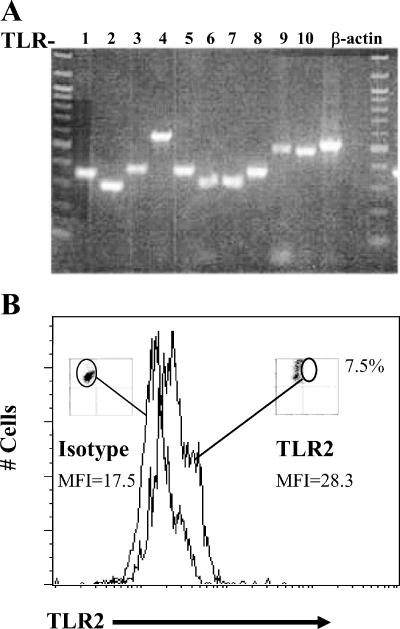

Expanded Vγ2Vδ2 T-cell lines were lysed or stained to look for TLR2 mRNA and protein expression. RNA was purified from whole-cell lysates, and cDNA was synthesized with an oligo(dT) primer. TLR cDNA was amplified with primer sets that detect Toll-like receptor family members 1 to 10. The β-actin gene was amplified as a control for input RNA. Vγ2Vδ2 T cells expressed mRNAs for TLR1 through TLR10, including TLR2 (Fig. 1A). However, flow cytometry analysis by conventional staining protocols failed to confirm TLR2 on the cell surface. A “live” staining procedure was used, during which unfixed Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were incubated at 37°C in the presence of FITC-conjugated antibody to TLR2 or an isotype control. This live stain showed that ∼8% of expanded Vγ2Vδ2 T cells expressed detectable TLR2 on the cell surface in our best result (Fig. 1B), though this experiment was difficult to repeat. We have observed TLR2-positive cells by the live stain procedure, by intracellular staining (not shown)s and by Western blotting (not shown). In each case, the presumed positive signals were close to the limit of detection for each assay and positive results were inconsistent in separate experiments. Using antibody detection approaches, we could not confirm TLR2 on the cell surface. Thus, we turned to functional studies.

FIG. 1.

Detection of TLR2 mRNA and protein in Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. (A) Reverse transcription-PCR amplification of TLR2 from IPP-expanded Vγ2Vδ2 T-cell effectors from one donor (ND001). The culture was >90% Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. Forward- and side-scatter profiles failed to detect any cells in the region expected for monocytes. TLR cDNA was amplified with TLR-specific primers for TLR1 to TLR10 and visualized on a 1% agarose gel. The β-actin gene was amplified as a control for input RNA. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of IPP-expanded Vγ2Vδ2 T-cell effectors from donor ND001. The histogram shows Vγ2Vδ2 T cells that stained positively for TLR2 with an increase in mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of >10.

Pam3Cys enhances IFN-γ production by Vγ2Vδ2 T cells.

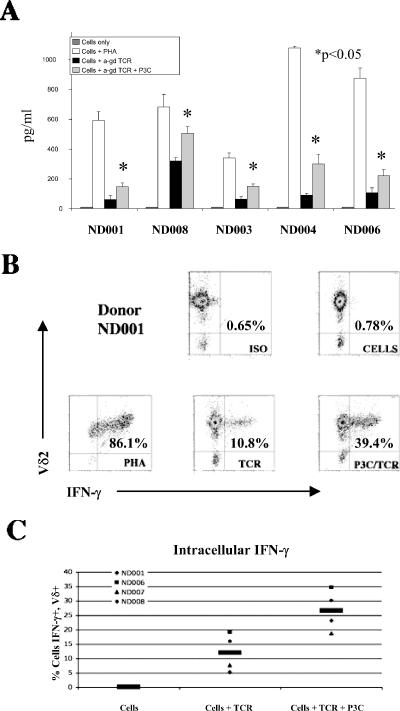

In an effort to understand the functional role for TLR2 on Vγ2Vδ2 T cells, we measured IFN-γ release after treatment with the TLR2 agonist Pam3Cys. Cells were obtained from five unrelated adult donors: ND001, ND003, ND004, ND006, and ND008. During a 2-hour incubation, Vγ2Vδ2 T cells produced up to 1,000 pg/ml of IFN-γ after stimulation with PHA. Antibody against the human γδ TCR induced lower but significant levels of IFN-γ release (Fig. 2A). These low levels of IFN-γ were increased in all five donors by an average of 2.4-fold after addition of the TLR2 agonist. In every donor, the increase in IFN-γ release after treatment with anti-γδ TCR plus Pam3Cys was statistically significant (P < 0.05) compared to that after treatment with anti-γδ TCR alone (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

IFN-γ expression by Pam3Cys-treated Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. (A) Vγ2Vδ2 T cells from five donors (ND001, ND008, ND003, ND004, and ND006). IFN-γ release was measured by ELISA after a 2-hour incubation in the absence of stimulation (cells only), in the presence of PHA (10 μg/ml) as a positive control (cells + PHA), in the presence of anti-γδ TCR stimulation (cells + anti-γδ TCR), or in the presence of anti-γδ TCR stimulation and 10 μg/ml Pam3Cys (cells + anti-γδ TCR + P3C). IFN-γ was measured as pg/ml in supernatants, and results are presented as averages for the triplicate wells for each donor and treatment group. Error bars depict the standard errors of the means among replicate experiments. (B) Vγ2Vδ2 T cells from donor ND001 were treated with brefeldin A to block Golgi transport and measure the intracellular accumulation of IFN-γ. These cells were surface stained with antibody to Vδ2 conjugated to PE or with an IgG1 isotype (ISO) control conjugated to PE (y axis) and intracellularly stained with antibody to IFN-γ conjugated to FITC or isotype control conjugated to FITC (x axis). (C) The percentage of cells positive for both Vδ2 and IFN-γ plotted across treatment groups illustrates the increased accumulation of IFN-γ with Pam3Cys treatment in four donors (ND001, ND006, ND007, and ND008) studied. Cells from donor ND003 were unavailable for this analysis. The black bars indicate the averages of the values from all four donors.

We repeated this experiment in the presence of brefeldin A to allow for intracellular accumulation of IFN-γ in expanded Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. We then stained cells with PE-conjugated antibody to Vδ2 and FITC-conjugated antibody to IFN-γ. Flow cytometry (Fig. 2B) showed that 86% of lymphocytes in this experiment were positive for Vγ2Vδ2 and intracellular IFN-γ after treatment with PHA. Stimulation with anti-γδ TCR alone gave only 10% double-positive cells, but that value was increased to around 40% double-positive cells after treatment with anti-γδ TCR plus Pam3Cys. This same trend was apparent for all donors studied (Fig. 2C).

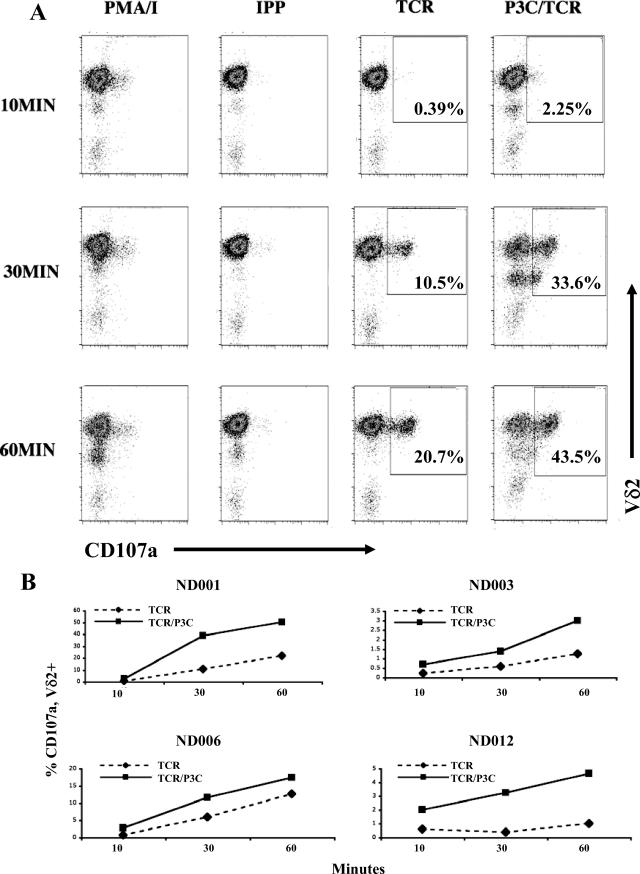

Treatment of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells with Pam3Cys plus anti-γδ TCR promotes degranulation.

We suspected that the combined effect of TLR2 and TCR stimulation might extend to other effector functions of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. We next looked at the expression of a functional marker of T-cell activation, CD107a. CD107a (lysosome-associated membrane protein-1) is normally sequestered in the lysosomal membrane but translocates to the extracellular membrane upon lysosome-extracellular membrane fusion during degranulation of cytolytic T cells (6, 29). The combination of PMA and ionomycin mimics potent TCR stimulation through dual protein kinase C activation and Ca2+ ionophore activity (11).

PMA-ionomycin increased cell surface CD107a expression within 10 min after treatment (Fig. 3A). On the other hand, IPP, a model phosphoantigen stimulator of Vγ2Vδ2 cells (32), caused only a slow increase in CD107a expression that required 2 h to approach the levels seen within 10 min of PMA-ionomycin stimulation. Stimulation with anti-γδ TCR alone increased expression of surface CD107a, and Pam3Cys further enhanced this response by causing a more rapid appearance (10 min) with a greater proportion of CD107a-positive cells by 1 h (Fig. 3A). TLR2 stimulation via Pam3Cys modified the kinetics of CD107a expression in cells costimulated with anti-γδ TCR. This change in kinetics was apparent in freshly expanded Vγ2Vδ2 cells for all donors studied. The frequency of cells staining positive for CD107a and Vδ2 was measured at 10, 30, and 60 min after stimulation with anti-γδ TCR alone or anti-γδ TCR plus Pam3Cys. Comparing CD107a expression on Vγ2Vδ2 cells at 10, 30, and 60 min for anti-γδ TCR stimulation alone and treatment with anti-γδ TCR plus Pam3Cys, we observed that the addition of Pam3Cys caused a 2- to 10-fold increase in the frequency of CD107a+ cells for four unrelated donors (Fig. 3B). Three of four donors showed a large increase in CD107a expression in the presence of Pam3Cys, and the effect was smaller but still apparent in the fourth donor, ND006.

FIG. 3.

Pam3Cys treatment increases the rate and magnitude of cell surface CD107a appearance. (A) Expanded Vγ2Vδ2 T cells from donor ND001 were placed in wells at 3 × 105 cells/well in a volume of 250 μl. Cells were treated with either PMA plus ionomycin (10 ng/ml and 1 μg/ml, respectively), IPP (10 μM), anti-γδ TCR, or anti-γδ TCR plus Pam3Cys (P3C) and were stained at 10 min, 30 min, 1 h, 2 h (not shown), and 4 h (not shown) after stimulation. Cells were stained with PE-labeled antibody directed to Vδ2 (y axis) and FITC-labeled antibody directed to CD107a (x axis). Staining with isotype resulted in no demonstrable shift. For anti-γδ TCR and anti-γδ TCR plus Pam3Cys, the percentage of cells present in the upper-right-hand quadrant (Vδ2+ CD107a+) is given. (B) Accumulation of Vδ2+ CD107a+ cells over time after treatment with anti-γδ TCR or anti-γδ TCR plus Pam3Cys for four unrelated donors (ND001, ND003, ND006, and ND012). These are individual flow cytometry studies, and hence there are no error bars. Similar results were obtained in repeated experiments with these donors.

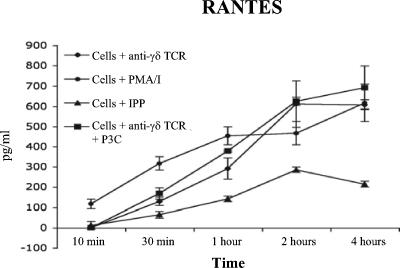

Rapid release of RANTES is not affected by TLR2 signaling.

Supernatants were collected from the CD107a assay (Fig. 3A) for donor ND001, and we measured cell-free RANTES at each time point (Fig. 4). RANTES is present within intracellular compartments of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells and is released within minutes of PHA or anti-γδ TCR signaling in the absence of de novo transcription or translation (32a). At very early time points, PMA-ionomycin triggered the release of stored RANTES, which reached a plateau by 1 hour and then increased again by 2 to 4 h with the onset of de novo gene expression and new protein synthesis (Fig. 4). IPP at 15 μM barely elicited a measurable release of RANTES within 1 to 2 h. Antibody stimulation of the γδ TCR resulted in the immediate release of stored RANTES, but there was no effect of adding the TLR2 agonist Pam3Cys.

FIG. 4.

Pam3Cys treatment does not affect RANTES release by Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. ELISA shows the release of RANTES from cells stimulated by PMA-ionomycin, IPP, anti-γδ TCR alone, or anti-γδ TCR plus Pam3Cys (PC3) as described for Fig. 3. Pam3Cys stimulation does not appear to enhance the kinetics of RANTES release. Anti-γδ TCR stimulation releases RANTES but does so less effectively than PMA-ionomycin. Error bars depict the standard errors of the means among replicate experiments.

DISCUSSION

The functional presence of TLR2 has already been reported for CD3+ αβ T cells (21, 37). Recently, Vγ2Vδ2 T cells have been shown to respond to TLR3 ligands with increased proliferation and higher expression of IFN-γ (36). Here, we report a specific response of human Vγ2Vδ2 T cells to the TLR2 agonist Pam3Cys. The response to Pam3Cys required coincident stimulation of the γδ T-cell receptor. The addition of Pam3Cys did not alter the immediate release of cytoplasmic stored RANTES, a rapid response to TCR stimulation in Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. However, dual stimulation with anti-TCR antibodies plus Pam3Cys increased the synthesis and secretion of IFN-γ and elevated the levels of cell surface CD107a expression. IFN-γ secretion and cell surface CD107a levels are markers of increased effector function in Vγ2Vδ2 T cells; both were enhanced by the combination of TLR2 and TCR signaling compared to the TCR signal alone.

As reported by others (17), it has been difficult to document the presence of TLR2 on the surface of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. Conventional staining protocols used by us included a 15- to 30-min incubation of cells with the staining antibody at 4°C and were inconclusive. However, by staining living cells at 37°C (suggested by Mario Roederer, Vaccine Research Center, NIH), we improved the result and detected TLR2 on a subpopulation of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. It is possible that the live stain worked in this instance because it accommodates rapid recycling of TLR2 that may be present at only low density on the cell surface. To our knowledge, TLR2 has been demonstrated on the surface of T cells by antibody staining only once in the literature, and only a small percentage of lymphocytes were positive in that study (21). These results are similar to our data for Vγ2Vδ2 T cells.

Vγ2Vδ2 T cells responded rapidly to the TLR2 agonist Pam3Cys, and this may distinguish them from the αβ T-cell responses. Cytokine expression in αβ T cells increased by 72 h after treatment with IFN-α, anti-CD3, and Pam3Cys (21), but only a 2-hour incubation of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells with anti-γδ TCR stimulation and Pam3Cys enhanced IFN-γ expression. Treatment of cell cultures with brefeldin A decreased the chance that a secondary factor was being released by other TLR-responsive cells but does not completely eliminate this possibility. However, we observed that expanded cells stimulated with anti-γδ TCR and Pam3Cys after 30 days of rest with a low IL-2 concentration have 10-fold higher numbers of IFN-γ-positive Vγ2Vδ2 T cells than those stimulated with anti-γδ TCR alone (compared to 2- or 4-fold in freshly expanded cells). Thirty days in culture resulted in the loss of most adherent cells, with enrichment of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. Freezing-sensitive cells will also have been depleted in these cultures, since the intracellular IFN-γ stain was performed only on cells that had been frozen at −130°C before the experiment. Intracellular staining of IFN-γ showed specific accumulation of this cytokine in Vγ2Vδ2 cells after treatment with Pam3Cys. Other groups noted that prolonged coculture with dendritic cells (48 h) was required to enhance Vγ2Vδ2 IFN-γ production (31). In our studies, we used short-term incubations for as little as 10 minutes with Pam3Cys or anti-γδ TCR stimulators to minimize any impact of contaminating dendritic or monocytic cells. Thus, cytokine production in these cell cultures likely reflects Vγ2Vδ2 T cells that respond directly to stimulation with anti-γδ TCR plus Pam3Cys.

The effector functions of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells include cytokine production and cytotoxicity. If stimulation with the TLR2 agonist plus anti-γδ TCR promotes Vγ2Vδ2 T-cell effector maturation, then one would expect cytotoxicity to be enhanced. CD107a has been used as a marker for degranulation and cytotoxicity (9). Data presented here argue that the appearance of CD107a on the surface of Vδ2 T cells is enhanced by cotreatment with anti-γδ TCR and the TLR2 agonist. In fact, though PMA-ionomycin stimulation resulted in an early release of the stored chemokine RANTES, anti-γδ TCR treatment had a greater effect than PMA-ionomycin treatment in the appearance of CD107a by 30 min. By 2 hours in cultures treated with Pam3Cys, most Vγ2Vδ2 T cells expressed CD107a on their surface. At present, we have been unable to show a positive effect on tumor cell cytotoxicity, because the TCR-stimulating antibody blocks tumor cell recognition and cytotoxicity.

Our data show rapid responses of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells (both cytokine expression and degranulation) upon TCR-plus-TLR2 signaling. It is interesting to note the pattern of functional responses to various stimulation conditions. PMA-ionomycin treatment resulted in a small increase of degranulation but a rapid and sustained release of RANTES over the same time course. Initial stimulation with anti-γδ TCR resulted in a steady increase in both degranulation and RANTES release. Pam3Cys enhanced anti-γδ TCR-driven degranulation and IFN-γ expression but not RANTES release. Future studies are needed to explore the interaction between TLR2 and TCR signal transduction pathways. The mature state of circulating Vγ2Vδ2 T cells (14) and their capacity for TLR2 signaling are two features that help explain their rapid responses to bacterial pathogens.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stephanie Vogel as well as Andrei Medvedev and Zach Roberts, University of Maryland at Baltimore, for advice and initial samples of Pam3Cys and control cell lines.

This work was supported by PHS grants AI51212 and CA113261 (to C.D.P.).

Editor: J. F. Urban, Jr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akira, S. 2001. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Adv. Immunol. 78:1-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aliprantis, A. O., R. B. Yang, M. R. Mark, S. Suggett, B. Devaux, J. D. Radolf, G. R. Klimpel, P. Godowski, and A. Zychlinsky. 1999. Cell activation and apoptosis by bacterial lipoproteins through toll-like receptor-2. Science 285:736-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes, P. F., C. L. Grisso, J. S. Abrams, H. Band, T. H. Rea, and R. L. Modlin. 1992. Gamma delta T lymphocytes in human tuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 165:506-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertotto, A., R. Gerli, G. Castellucci, S. Crupi, F. Scalise, F. Spinozzi, G. Fabietti, N. Forenza, and R. Vaccaro. 1993. Mycobacteria-reactive gamma/delta T cells are present in human colostrum from tuberculin-positive, but not tuberculin-negative nursing mothers. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 29:131-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bertotto, A., R. Gerli, F. Spinozzi, C. Muscat, F. Scalise, G. Castellucci, M. Sposito, F. Candio, and R. Vaccaro. 1993. Lymphocytes bearing the gamma delta T cell receptor in acute Brucella melitensis infection. Eur. J. Immunol. 23:1177-1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Betts, M. R., J. M. Brenchley, D. A. Price, S. C. De Rosa, D. C. Douek, M. Roederer, and R. A. Koup. 2003. Sensitive and viable identification of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells by a flow cytometric assay for degranulation. J. Immunol. Methods 281:65-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bukowski, J. F., C. T. Morita, H. Band, and M. B. Brenner. 1998. Crucial role of TCR gamma chain junctional region in prenyl pyrophosphate antigen recognition by gamma delta T cells. J. Immunol. 161:286-293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bukowski, J. F., C. T. Morita, and M. B. Brenner. 1999. Human gamma delta T cells recognize alkylamines derived from microbes, edible plants, and tea: implications for innate immunity. Immunity 11:57-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burkett, M. W., K. A. Shafer-Weaver, S. Strobl, M. Baseler, and A. Malyguine. 2005. A novel flow cytometric assay for evaluating cell-mediated cytotoxicity. J. Immunother. 28:396-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casorati, G., G. De Libero, A. Lanzavecchia, and N. Migone. 1989. Molecular analysis of human gamma/delta+ clones from thymus and peripheral blood. J. Exp. Med. 170:1521-1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chatila, T., L. Silverman, R. Miller, and R. Geha. 1989. Mechanisms of T cell activation by the calcium ionophore ionomycin. J. Immunol. 143:1283-1289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chien, Y. H., R. Jores, and M. P. Crowley. 1996. Recognition by gamma/delta T cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 14:511-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Libero, G., G. Casorati, C. Giachino, C. Carbonara, N. Migone, P. Matzinger, and A. Lanzavecchia. 1991. Selection by two powerful antigens may account for the presence of the major population of human peripheral gamma/delta T cells. J. Exp. Med. 173:1311-1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Rosa, S. C., J. P. Andrus, S. P. Perfetto, J. J. Mantovani, L. A. Herzenberg, L. A. Herzenberg, and M. Roederer. 2004. Ontogeny of gamma delta T cells in humans. J. Immunol. 172:1637-1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans, P. S., P. J. Enders, C. Yin, T. J. Ruckwardt, M. Malkovsky, and C. D. Pauza. 2001. In vitro stimulation with a non-peptidic alkylphosphate expands cells expressing Vgamma2-Jgamma1.2/Vdelta2 T-cell receptors. Immunology 104:19-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gober, H. J., M. Kistowska, L. Angman, P. Jeno, L. Mori, and G. De Libero. 2003. Human T cell receptor gammadelta cells recognize endogenous mevalonate metabolites in tumor cells. J. Exp. Med. 197:163-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hedges, J. F., K. J. Lubick, and M. A. Jutila. 2005. Gamma delta T cells respond directly to pathogen-associated molecular patterns. J. Immunol. 174:6045-6053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirschfeld, M., J. J. Weis, V. Toshchakov, C. A. Salkowski, M. J. Cody, D. C. Ward, N. Qureshi, S. M. Michalek, and S. N. Vogel. 2001. Signaling by Toll-like receptor 2 and 4 agonists results in differential gene expression in murine macrophages. Infect. Immun. 69:1477-1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho, M., P. Tongtawe, J. Kriangkum, T. Wimonwattrawatee, K. Pattanapanyasat, L. Bryant, J. Shafiq, P. Suntharsamai, S. Looareesuwan, H. K. Webster, and J. F. Elliott. 1994. Polyclonal expansion of peripheral γδT cells in human Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Infect. Immun. 62:855-862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kato, Y., Y. Tanaka, H. Tanaka, S. Yamashita, and N. Minato. 2003. Requirement of species-specific interactions for the activation of human gamma delta T cells by pamidronate. J. Immunol. 170:3608-3613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Komai-Koma, M., L. Jones, G. S. Ogg, D. Xu, and F. Y. Liew. 2004. TLR2 is expressed on activated T cells as a costimulatory receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:3029-3034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medzhitov, R., P. Preston-Hurlburt, and C. A. Janeway, Jr. 1997. A human homologue of the Drosophila Toll protein signals activation of adaptive immunity. Nature 388:394-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morita, C. T., E. M. Beckman, J. F. Bukowski, Y. Tanaka, H. Band, B. R. Bloom, D. E. Golan, and M. B. Brenner. 1995. Direct presentation of nonpeptide prenyl pyrophosphate antigens to human gamma delta T cells. Immunity 3:495-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panchamoorthy, G., J. McLean, R. L. Modlin, C. T. Morita, S. Ishikawa, M. B. Brenner, and H. Band. 1991. A predominance of the T cell receptor V gamma 2/V delta 2 subset in human mycobacteria-responsive T cells suggests germline gene encoded recognition. J. Immunol. 147:3360-3369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poltorak, A., I. Smirnova, X. He, M. Y. Liu, C. Van Huffel, O. McNally, D. Birdwell, E. Alejos, M. Silva, X. Du, P. Thompson, E. K. Chan, J. Ledesma, B. Roe, S. Clifton, S. N. Vogel, and B. Beutler. 1998. Genetic and physical mapping of the Lps locus: identification of the toll-4 receptor as a candidate gene in the critical region. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 24:340-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poquet, Y., M. Kroca, F. Halary, S. Stenmark, M. A. Peyrat, M. Bonneville, J. J. Fournie, and A. Sjostedt. 1998. Expansion of Vγ9 Vδ2 T cells is triggered by Francisella tularensis-derived phosphoantigens in tularemia but not after tularemia vaccination. Infect. Immun. 66:2107-2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rakasz, E., A. V. MacDougall, M. T. Zayas, J. L. Helgelund, T. J. Ruckward, G. Hatfield, M. Dykhuizen, J. L. Mitchen, P. S. Evans, and C. D. Pauza. 2000. Gammadelta T cell receptor repertoire in blood and colonic mucosa of rhesus macaques. J. Med. Primatol. 29:387-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raziuddin, S., S. Shetty, and A. Ibrahim. 1992. Phenotype, activation and lymphokine secretion by gamma/delta T lymphocytes from schistosomiasis and carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Eur. J. Immunol. 22:309-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rubio, V., T. B. Stuge, N. Singh, M. R. Betts, J. S. Weber, M. Roederer, and P. P. Lee. 2003. Ex vivo identification, isolation and analysis of tumor-cytolytic T cells. Nat. Med. 9:1377-1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schild, H., N. Mavaddat, C. Litzenberger, E. W. Ehrich, M. M. Davis, J. A. Bluestone, L. Matis, R. K. Draper, and Y. H. Chien. 1994. The nature of major histocompatibility complex recognition by gamma delta T cells. Cell 76:29-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shrestha, N., J. A. Ida, A. S. Lubinski, M. Pallin, G. Kaplan, and P. A. Haslett. 2005. Regulation of acquired immunity by gammadelta T-cell/dendritic-cell interactions. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1062:79-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanaka, Y., C. T. Morita, Y. Tanaka, E. Nieves, M. B. Brenner, and B. R. Bloom. 1995. Natural and synthetic non-peptide antigens recognized by human gamma delta T cells. Nature 375:155-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33a.Tikhonov, I., C. O. Deetz, R. Paca, S. Berg, V. Lukyanenko, J. K. Lim, and C. D. Pauza. 1 June 2006. Human Vγ2Vδ2 T cells contain cytoplasmic RANTES. Int. Immunol. [Epub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Wallace, M., S. R. Bartz, W. L. Chang, D. A. Mackenzie, C. D. Pauza, and M. Malkovsky. 1996. Gamma delta T lymphocyte responses to HIV. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 103:177-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang, L., H. Das, A. Kamath, and J. F. Bukowski. 2001. Human V gamma 2V delta 2 T cells produce IFN-gamma and TNF-alpha with an on/off/on cycling pattern in response to live bacterial products. J. Immunol. 167:6195-6201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Werts, C., R. I. Tapping, J. C. Mathison, T. H. Chuang, V. Kravchenko, I. Saint Girons, D. A. Haake, P. J. Godowski, F. Hayashi, A. Ozinsky, D. M. Underhill, C. J. Kirschning, H. Wagner, A. Aderem, P. S. Tobias, and R. J. Ulevitch. 2001. Leptospiral lipopolysaccharide activates cells through a TLR2-dependent mechanism. Nat. Immunol. 2:346-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wesch, D., S. Beetz, H. H. Oberg, M. Marget, K. Krengel, and D. Kabelitz. 2006. Direct costimulatory effect of TLR3 ligand poly(I:C) on human gammadelta T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 176:1348-1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zanin-Zhorov, A., G. Tal, S. Shivtiel, M. Cohen, T. Lapidot, G. Nussbaum, R. Margalit, I. R. Cohen, and O. Lider. 2005. Heat shock protein 60 activates cytokine-associated negative regulator suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 in T cells: effects on signaling, chemotaxis, and inflammation. J. Immunol. 175:276-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]