Abstract

Legionella pneumophila is a gram-negative facultative intracellular human pathogen that can cause fatal Legionnaires' disease. Polypeptide deformylase (PDF) is a novel broad-spectrum antibacterial target, and reports of inhibitors of PDF with potent activities against L. pneumophila have been published previously. Here, we report the identification of not one but three putative pdf genes, pdfA, pdfB, and pdfC, in the complete genome sequences of three strains of L. pneumophila. Phylogenetic analysis showed that L. pneumophila PdfA is most closely related to the commonly known γ-proteobacterial PDFs encoded by the gene def. PdfB and PdfC are more divergent and do not cluster with any specific bacterial or eukaryotic PDF. All three putative pdf genes from L. pneumophila strain Philadelphia 1 have been cloned, and their encoded products have been overexpressed in Escherichia coli and purified. Enzymatic characterization shows that the purified PDFs with Ni2+ substituted are catalytically active and able to remove the N-formyl group from several synthetic polypeptides, although they appear to have different substrate specificities. Surprisingly, while PdfA and PdfB with Zn2+ substituted are much less active than the Ni2+ forms of each enzyme, PdfC with Zn2+ substituted was as active as the Ni2+ form for the fMA substrate and exhibited substrate specificity different from that of Ni2+ PdfC. Furthermore, the catalytic activities of these enzymes are potently inhibited by a known small-molecule PDF inhibitor, BB-3497, which also inhibits the extracellular growth of L. pneumophila. These results indicate that even though L. pneumophila has three PDFs, they can be effectively inhibited by PDF inhibitors which can, therefore, have potent anti-L. pneumophila activity.

Legionellae are gram-negative opportunistic human pathogens that possess the metabolic flexibility to multiply in either protozoa or mammalian macrophages and to survive in very harsh environments. They reside in natural aquatic environments as an intracellular parasite of protozoa (11). When transmitted by aerosols to susceptible human hosts, legionellae infect alveolar macrophages, causing life-threatening Legionnaires' disease (3, 9). Furthermore, legionellae are able to survive in biofilms for extended periods, where they are resistant to biocidal agents, posing a significant hazard to public health (24).

The initial publication of the complete genomic sequence of Legionella pneumophila strain Philadelphia 1 revealed several genes that might account for survival and replication in these diverse environments (7). Subsequently, the genomes of two endemic and epidemic strains from France, L. pneumophila strain Paris and strain Lens, have also been released (4). These genomic sequences provide opportunities for the identification of novel anti-L. pneumophila targets.

Polypeptide deformylase (PDF) is a protease-like metalloenzyme that catalyzes the removal of the N-formyl group from the N-terminal methionine of nascent polypeptides in bacteria. All bacterial genomes sequenced thus far contain at least one pdf gene, and some species have up to four (18). Based on structural and sequence analysis, PDF enzymes can be grouped into two major classes (14, 18). Class I PDFs are found in gram-negative and some gram-positive bacteria and in mitochondria and plastids of most eukaryotic organisms (13, 18, 25, 32). In contrast, class II PDFs are found only in gram-positive bacteria.

Recently, there has been considerable interest in developing PDF inhibitors as novel broad-spectrum antibacterial agents (2, 37). PDF is essential for bacterial-cell viability in Escherichia coli, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Staphylococcus aureus (5, 6, 22). Moreover, actinonin, a naturally occurring antibiotic that is a potent time-dependent inhibitor of PDF (35), inhibits bacterial growth by targeting the enzyme (6). Several newly derived PDF inhibitors have been shown to possess in vitro activity and to be efficacious in animal models against several gram-positive pathogens (17, 19, 21). Comparative studies of inhibitor binding in class I and II polypeptide deformylases from different bacterial species suggest that it is possible to design deformylase inhibitor molecules active against a broad spectrum of bacterial pathogens (33).

PDF inhibitors with potent anti-L. pneumophila activity have been reported (12). However, until now, the mode of action of PDF inhibitors against this pathogen has not been examined. Using bioinformatics, we identified three putative pdf genes in the genomes of the three aforementioned strains of L. pneumophila (4, 7). We have cloned these genes, expressed the proteins, and shown that all three purified Ni2+ PDF isoforms have enzymatic activity. Surprisingly, while PdfA and PdfB with Zn2+ substituted are much less active than the Ni2+ forms of each enzyme, PdfC with Zn2+ substituted was as active as the Ni2+ form for the fMA substrate and exhibited different substrate specificity from Ni2+ PdfC. Furthermore, we have shown that all three PDF isozymes are potently inhibited by a known PDF inhibitor, BB-3497 (8), suggesting that the observed anti-L. pneumophila activity of this compound is a consequence of its effective inhibition of multiple PDF targets.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and reagents.

The peptide substrates fMA, fMAS, and fMAKY were purchased from American Peptide, Sunnyvale, CA. Formate dehydrogenase and NAD were from Roche, Indianapolis, IN. Brij detergent and actinonin were obtained from Sigma, St. Louis, MO. BB-3497 was synthesized at GlaxoSmithKline. All other reagents were standard laboratory grade.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

Legionella pneumophila Philadelphia 1 (ATCC 33152) was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA. Escherichia coli DH 10B competent cells (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and BL21(DE3) (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) were used for plasmid transformation. The plasmid pCR-Blunt (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used for cloning PCR products, and pET-26b and pET-28a (Novagen, Madison, WI) were used for expression of L. pneumophila PDFs. E. coli was grown at 37°C in Luria broth (LB) supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg/ml) for pCR-Blunt and with kanamycin (50 μg/ml) and 1% glucose for the pET vectors. L. pneumophila was grown at 37°C on buffered charcoal-yeast extract agar plates or in BYE broth (buffered yeast extract broth minus charcoal and agar).

Initial identification of L. pneumophila pdf genes.

The sequences of E. coli PDF (GenBank accession no. NP_417745) and S. aureus PDF (GenBank accession no. YP_040602) were used as queries to search the L. pneumophila strain Philadelphia 1 genome at the Columbia Genome Center (http://genome3.cpmc.columbia.edu/∼legion/) using BLAST (1). Three putative pdf genes were identified, named pdfA (lpg2595), pdfB (lpg0615), and pdfC (lpg1064). The following primers were synthesized and used in PCR amplifications of the complete pdf open reading frames (ORFs) from chromosomal DNA of L. pneumophila Philadelphia 1: LppdfAorfp1, 5′-ATCCCTTTAGTTGAGCCTTAGC-3′; LppdfAorfp2, 5′-AGCAAAAACGACAGTTAAACC-3′; LppdfBorfp1, 5′-ATATTTACAGGACTTACGAAAAACC-3′; LppdfBorfp2, 5′-GGATTATCTCAAGTTGTTACC-3′; LppdfCorfp1, 5′-CGATTCATTGCGAAAAACTGTTAGC-3′; and LppdfCorfp2, 5′-AACAAACCCTTGGAGACATCACC-3′. The sequences of the PCR products were determined on both strands.

Sequence retrieval and database searches.

All PDF homologs were initially collected from the GenBank nonredundant protein database by performing separate BLASTP searches with L. pneumophila PdfA, PdfB, and PdfC proteins as query sequences and a cutoff E value of 1.0e-05. Significant hits from all three searches were combined into a single FASTA file, and duplicate PDF sequences were then removed. Also searched for putative PDF homologs were the complete genome sequences of the three strains of L. pneumophila: Philadelphia 1 (7), Paris, and Lens (4). A total of 284 unique PDF sequences were used in the initial multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic analyses. For presentation purposes, 85 representative species were selected for the final phylogenetic tree.

Phylogenetic and structure analyses.

Initial multiple sequence alignments were performed using the program CLUSTALW v1.7 (34), with default settings then refined manually using the program SEQLAB of the GCG Wisconsin Package v11.0 software package (Accelrys, San Diego, CA). Regions with residues that could not be unambiguously aligned or that contained insertions or deletions were removed. The final multiple sequence alignment was 89 amino acids in length. Pairwise comparisons for the proportion of similar residues were estimated from the length of the shortest sequence without gaps and the Blosum62 weighting matrix as implemented in the program OLDDISTANCES in the GCG package.

Phylogenetic trees were constructed using distance neighbor joining based on pairwise distances between amino acid sequences as determined by the programs NEIGHBOR and PROTDIST (Dayhoff option), respectively, of the PHYLIP 3.6 package (10). The programs SEQBOOT and CONSENSE were used to estimate the confidence limits of branching points from 1,000 bootstrap replications. The phylogenetic tree was drawn using the program TREEVIEW v1.6.6 (27).

Cloning, expression, and purification of L. pneumophila PDFs.

The pdfA, pdfB, and pdfC genes were amplified by PCR with the high-fidelity DNA polymerases in Supermix (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) using chromosomal DNA from L. pneumophila Philadelphia 1 as a template and the following primers: LppdfAp1, 5′-AACCATGGCAATTCGCAAGATTC-3′; LppdfAp2, 5′-AAGGATCCAGCAAAAACGACAGTTAAACC-3′; LppdfBp1, 5′-ACCACCATATGTTAAAAACTCG-3′; LppdfBp2, 5′-AAGAGCTCTTATCATTGAAATCAATTC-3′; LppdfCp1, 5′-AACATATGAACACACTCCTTGATAAAAAC-3′; and LppdfCp2, 5′-AAGAGCTCATGCGATTATCCTTTACTTTG-3′. The PCR products were purified, ligated onto the pCR-blunt vector, and used to transform E. coli DH10B. The resultant plasmids were sequenced to confirm their wild-type pdf sequences. Then, the NcoI-BamHI fragment containing pdfA was inserted into the pET28a vector to generate pET-pdfA. Similarly, the NdeI-SstI fragments containing pdfB or pdfC were cloned, separately, into the pET26b vector to give pET-pdfB and pET-pdfC.

For PdfA and PdfC expression, E. coli BL21(DE3) cells carrying the corresponding pET-pdf plasmids were grown in LB supplemented with 1% glucose and 50 μg/ml kanamycin at 37°C to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.8, at which point 0.1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) was added and incubation was continued at 37°C for 3 h. For PdfB expression, cultures were grown at 37°C to an OD600 of approximately 0.3, at which time the temperature was dropped to 17°C. The cultures continue to grow to an OD600 of approximately 0.6, and then protein expression was induced with 1.0 mM IPTG at 17°C for 19 h. To ensure the purification of active protein, 0.1 mM nickel chloride was added in all cases at the time of induction. After induction, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4°C.

The following procedure was used in the purification of PdfA and PdfB. All the purification steps were performed at 4°C. E. coli cells overexpressing PdfA or PdfB were homogenized and subsequently lysed by two passages through a high-pressure homogenizer (Avestin, Ottawa, Canada) at 12,000 lb/in2 in 10 volumes of buffer A (20 mM KH2PO4, pH 6.8, 5 mM nickel acetate) plus protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). The cell lysate was centrifuged at 34,000 × g for 45 min, and the supernatant was loaded onto an SP Sepharose Fast Flow column (50-ml bed volume; Amersham Biosciences). The column was washed with buffer A, and proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of 0 to 1.0 M NaCl in buffer A. The fractions containing PdfA or PdfB were pooled, dialyzed against 20 volumes of buffer B (20 mM KH2PO4, pH 6.8) overnight, and centrifuged at 17,000 × g for 20 min. The supernatant was then loaded onto a Mono S HR 10/10 column (Amersham Biosciences), and bound proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of 0 to 1 M NaCl in buffer B. Fractions containing the desired protein were further purified by a HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 75 column (Amersham Biosciences) preequilibrated in buffer C (10 mM KH2PO4, pH 6.8, 150 mM NaCl). Eleven grams of E. coli cells overexpressing PdfA yielded 37 mg of >95% pure L. pneumophila PdfA, and 14 g of E. coli cells overexpressing PdfB yielded 57 mg of >95% pure L. pneumophila PdfB.

Purification of PdfC was carried out using the same protocol described above but using a Q Sepharose Fast Flow column (50-ml bed volume; Amersham Biosciences) and a Mono Q HR 10/10 column (Amersham Biosciences) in the first two chromatographic steps. Eleven grams of E. coli cells overexpressing PdfC yielded 72 mg of >95% pure L. pneumophila PdfC.

The procedures described above allowed isolation of Ni2+ PdfB, Zn2+ PdfC, and a mixture of Ni2+ and Zn2+ PdfA. For the preparation of Ni2+ PdfA and Ni2+ PdfC, PdfA and PdfC were expressed in M9 minimum medium (31) supplemented with 1% glucose and 50 μg/ml kanamycin to minimize the Zn contamination. For Ni2+ PdfA preparation, E. coli BL21(DE3) cells carrying the pET-pdfA plasmid were grown in M9 medium containing 0.5 μM NiSO4 at 37°C to an OD600 of 0.7, and then PdfA expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG in the presence of 0.1 mM NiSO4 at 37°C for 5 h. Cell lysate was prepared, and PdfA was purified using the same protocol described above except that the Mono S HR 10/10 column step was omitted.

For Ni2+ PdfC preparation, E. coli BL21(DE3) cells carrying the pET-pdfC plasmid were grown in M9 medium at 37°C to an OD600 of 0.7. Then, the cultures were cooled to 23°C and PdfC expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG in the presence of 0.01 mM NiSO4 at 23°C for 14 h. PdfC was purified using the same protocol described above.

The purified Ni2+/Zn2+ PdfA and Ni2+ PdfB from cells grown in LB were used to prepare Zn2+ PdfA and Zn2+ PdfB by the following procedures. All dialysis steps were performed at 4°C. Purified PDF was dialyzed against 50 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.6. In order to strip the bound Ni2+, 1,10-phenanthroline was added to the sample at a final concentration of 10 mM and incubated on ice for 3 h. The sample was then dialyzed against 50 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.6, overnight, with three buffer changes. At this stage, PdfA was in the Zn2+ form. For PdfB, zinc chloride was added to the sample at a final concentration of 5 mM and incubated on ice for 3 h. The sample was then dialyzed against 50 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.6, overnight, with two buffer changes to obtain Zn2+ PdfB.

All the enzyme preparations used in the studies were purified to >95% homogeneity. Their identities were confirmed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis and N-terminal sequencing, concentrations were determined by amino acid analysis, and metal contents were determined using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (Elemental Research Inc., Vancouver, Canada).

Enzymatic assays and inhibition studies.

PDF activity was measured in a FDH-coupled assay in which the formate released from the substrate was oxidized by FDH, thereby reducing one molecule of NAD to NADH and resulting in an increase in absorbance at 340 nm (20). To determine inhibition constants (Ki) and overall inhibition constants (Ki*), reactions were initiated by adding PDF to 96-well microtiter plates containing all of the other reaction components. The final reaction mixture composition for the L. pneumophila PdfA assay was 50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.6, 5 units/ml FDH, 15 mM NAD, 5% dimethyl sulfoxide, 0.006% Brij, 6 nM PdfA, and 7.3 mM fMAKY. Serial dilutions of inhibitors were in dimethyl sulfoxide. Reaction velocities were measured at 25°C in a Molecular Devices SpectraMax plate reader. The reagents and assay format were identical for L. pneumophila PdfB, with the following exceptions: 1.3 mM fMAKY (Km concentration for substrate), 125 μM NiCl2, and 15 nM PdfB. The reaction conditions for L. pneumophila PdfC were identical to those for L. pneumophila PdfA except that they contained 25 mM MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid), pH 7.4, 0.28 mM fMA, and 13 nM PdfC.

Time-dependent inhibition of PDF has been reported previously (15, 26, 35) and is best described by a two-step mechanism in which the initial encounter complex, EI, tightens to form EI* with a slow off rate (k6).

|

For this analysis, all reactions were started by the addition of enzyme. Initial reaction velocities were used to determine the initial binding Ki,app values. Since the PDF inhibitors are competitive versus substrate, the true Ki values were calculated using equation 1.

|

(1) |

The overall inhibition constants representing the two-step formation of EI* (Ki*) were calculated from final steady-state velocities, using equation 1 to correct for the presence of substrate.

In the situations where Ki* approached the enzyme concentration in the assay, fractional enzymatic activity observed in the presence of inhibitor (vi/v0) was fitted to Morrison's equation for tight binding inhibition (equation 2) to determine the apparent inhibition constant, Ki,app*.

|

(2) |

Overall inhibition constants (Ki*) were then calculated using equation 1.

RESULTS

Identification of three putative L. pneumophila pdf genes.

Searches of the L. pneumophila genome for the Philadelphia 1 strain at the Columbia Genome Center (http://genome3.cpmc.columbia.edu/∼legion/) revealed three putative pdf genes. For our purposes, these genes (and encoded proteins) are called pdfA or def (PdfA), pdfB (PdfB), and pdfC (PdfC). To confirm their presence, each of the three pdf genes was amplified by PCR from chromosomal DNA of L. pneumophila Philadelphia 1 (ATCC 33152) using specific DNA primer pairs. PCR product analysis showed that each primer pair allowed amplification of a specific DNA fragment of the predicted size (data not shown). Comparisons of the sequences determined for the PCR-amplified products to those published for L. pneumophila Philadelphia 1 (7) confirmed high percent identities at the nucleotide/amino acid levels for pdfA (99/100%), pdfB (96/94%), and pdfC (100/100%).

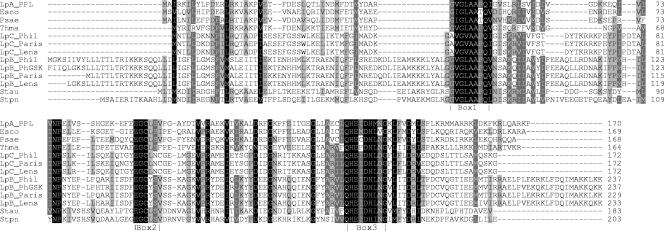

The genes pdfA and pdfC encode proteins of 170 and 172 amino acid residues, respectively, with a predicted mass of 19 kDa. However, there are four possible translation start sites for the pdfB gene. The largest pdfB ORF starts at a TTG and encodes a protein of 229 amino acid residues with a predicted mass of 26 kDa (Fig. 1). Although highly divergent from each other (see below), structure-based sequence alignments of the three L. pneumophila PDFs with known PDF structures revealed similarly strict conservation of residues in all three L. pneumophila PDF sequences (Fig. 1). In particular, PdfA is 100% identical to the consensus sequences of the three conserved motifs (Fig. 1, boxes 1, 2, and 3) (23, 37) that define the catalytic domain of deformylase. However, there is a change from the consensus in PdfB, L92 (using the E. coli PDF numbering) to a Y residue in box 2, and two changes from the consensus in PdfC, G44 to an A residue in box 1 and S93 to an N residue in box 2. It has been reported that multiple changes from the consensus in these boxes coincide with inactive deformylase (37). In addition, for all strains of L. pneumophila, PdfB has an extended C-terminal stretch of ∼24 amino acid residues that are rich in positively charged residues.

FIG. 1.

Multiple sequence alignment of Legionella pneumophila PDFs with representative bacterial class I and II PDFs. The class I PDFs are from Escherichia coli (Esco), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Psae), and Thermotoga maritima (Thma), while the class II PDFs are from Staphylococcus aureus (Stau) and Streptococcus pneumoniae (Stpn). These sequences are aligned with those of L. pneumophila PdfA (LpA), PdfB (LpB), and PdfC (LpC) from the L. pneumophila strains Paris (Paris), Lens (Lens), and Philadelphia 1 (Phil). The amino acid sequences of PdfA (LpA_PPL) are identical across all three strains. LpB_PhGSK is the amino acid sequence based on the DNA resequencing in this study of the pdfB gene from L. pneumophila strain Philadelphia 1, which differed from that of the previously published genome sequence (7). PdfA and PdfC were identical to previously determined sequences from L. pneumophila strain Philadelphia 1. The principal catalytic motifs of PDF, boxes 1, 2, and 3, are indicated. Progressively darker shading indicates conservation of amino acid residues in 60%, 80%, and 100% of the sequences. The program CLUSTALW (34) was used to construct the initial alignment, which was subsequently refined manually.

Genomic context of pdf genes in L. pneumophila strains.

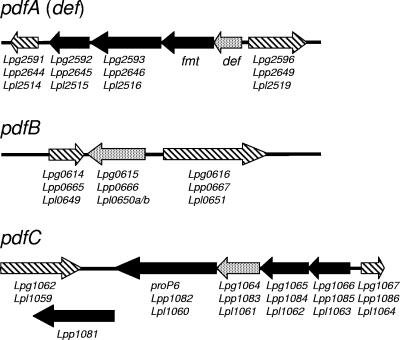

Recent comparative genomic analyses of the three L. pneumophila strains suggested extensive intraspecific gene losses and gains (4). However, pdf ORFs are highly conserved in both occurrence and genomic context (Fig. 2). ORFs corresponding to the pdfA gene were found in all three L. pneumophila strains, located in a conserved, putative four-gene operon. In transcriptional order, the genes (proteins) of this operon are pdfA (PdfA), fmt (methionyl-tRNA formyltransferase), an unnamed ORF (rRNA methyltransferase [SUN] protein), and a hypothetical ORF. The last gene is conserved among all L. pneumophila strains but has no significant homology to genes in other species.

FIG. 2.

Genomic contexts of the three polypeptide deformylase genes (pdfA, pdfB, and pdfC) in three different strains of Legionella pneumophila. The arrows indicate the directions of transcriptional polarity. pdf genes are stippled, and proposed cotranscribed ORFs are solid. Flanking genes that are unlikely to be cotranscribed are crosshatched. Under each ORF is the recorded gene name (GeneID in GenBank) as annotated for the genomes of L. pneumophila Philadelphia 1 (Lpg), L. pneumophila Paris (Lpp), and L. pneumophila Lens (Lpl). Other gene names are peptide deformylase (def), methionyl-tRNA formyltransferase (fmt), and proline/betaine transporter 6 (proP6). In L. pneumophila Lens, N- and C-terminal portions of PdfB are annotated as two separate pseudogenes (Lpl0650a and Lpl0650b), which in fact is most likely a frameshift error in the DNA sequencing of a poly(A) 9-mer.

The genes pdfB and pdfC are also conserved in all three strains, although they are presently annotated as hypothetical genes. Unlike pdfA, the gene pdfB does not appear to be cotranscribed in either L. pneumophila Philadelphia 1 (gene lpg0615) or L. pneumophila Paris (gene lpp0666). In L. pneumophila Lens, two adjacent ORFs annotated as the pseudogenes lpl0650a and lpl0650b correspond to the N- and C-terminal portions of PdfB, respectively. Closer inspection of the coding regions of these genes revealed a frame shift in a variable-length block comprised of 10 and 9 adenosines [poly(A)] in lpl0650a and lpl0650b, respectively. The same region in the orthologous genes of L. pneumophila strain Philadelphia 1 and strain Paris also has a run of nine poly(A)s. Thus, removing a single residue from this poly(A) run in lpl0650a would effectively resolve these two pseudogenes into a single, complete pdfB gene. Therefore, we suggest that the splitting of the gene pdfB in L. pneumophila Lens into two pseudogenes is likely an artifact of errors in either DNA sequencing or assembly.

The gene pdfC is also conserved in L. pneumophila strain Philadelphia 1 (gene lpg1064), strain Paris (gene lpp1083), and strain Lens (gene lpl1061) and appears to be part of a common four-gene operon. In transcriptional order, these genes encode a hypothetical protein/putative transcriptional regulator, hypothetical protein, PdfC, and proline/betamine transporter P6. In L. pneumophila Paris, there is a gene, Lpp1081, downstream of ProP6, which might be cotranscribed with the putative pdfC operon. The gene Lpp1081 is unique to L. pneumophila Paris and has no other sequence homologs in public databases (including the genomes of other L. pneumophila strains).

Sequence conservation and evolution.

Multiple sequence alignments show relatively high conservation of amino acids between all the various Legionella PDFs and the PDFs from other bacteria (Fig. 1). Furthermore, those amino acid residues implicated in the binding of the antibiotic actinonin to PDF are also conserved in all three Legionella isoforms. However, among these isoforms, there are slight differences in amino acid sequence conservation between strains. PdfAs are identical among all three strains. For PdfB, L. pneumophila strain Philadelphia 1 and strain Paris were more similar to each other (97% amino acid identity) than either was to L. pneumophila Lens (both 94% amino acid identity). For PdfC, L. pneumophila strain Philadelphia 1 and strain Lens were more similar to each other (98% amino acid identity) than either was to L. pneumophila Paris (93 to 94% amino acid identity).

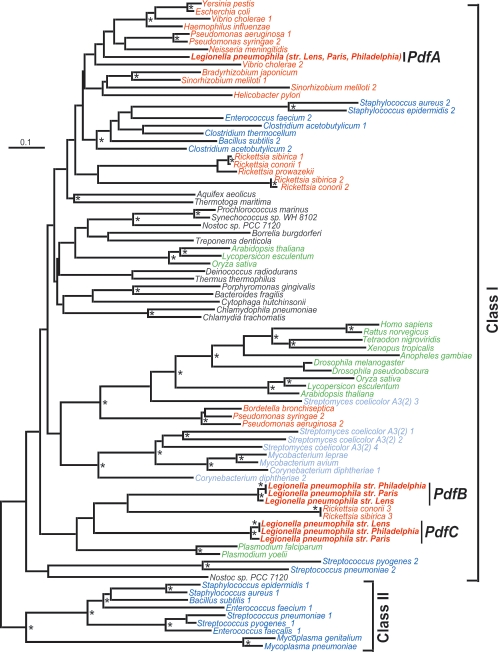

Due to the small size of PDF, the limited number of confidently aligned amino acid residues (n = 89), and the large number of taxa (n = 85), most major nodes in the PDF phylogenetic tree have low bootstrap confidence limits (Fig. 3). However, our phylogenetic analysis did show significant support for the separation of the two major PDF subclasses, classes I and II (18), as well as several subgroups, such as eukaryotic PDFs targeted to the mitochondria (Fig. 3). All three L. pneumophila PDFs belong to class I, although they fall in different branches within that subgroup (class II PDFs are exclusive to low-G+C gram-positive bacteria.). L. pneumophila PdfA is most closely related to other proteobacterial PDFs encoded by the gene def. PdfB and PdfC are more divergent groups and do not cluster with any specific bacterial or eukaryotic species.

FIG. 3.

Phylogenetic tree of PDFs from representative species. The major organism groups are Legionella pneumophila (red; bold italic), proteobacteria (red; italic), low-G+C gram-positive bacteria (dark blue; italic), high-G+C gram-positive bacteria (light blue; italic), all other bacteria (black; italic), and eukaryotic mitochondrial PDF (green; italic). The major subgroups of class I and II PDFs are indicated, as are Legionella pneumophila PdfA, PdfB, and PdfC from three strains (Lens, Paris, and Philadelphia [strain Philadelphia 1]). The phylogenetic tree was reconstructed using the neighbor-joining method and pairwise protein divergence as implemented by the programs NEIGHBOR and PROTDIST of the PHYLIP package (10) (see Materials and Methods). Those nodes which occurred in 60% or more of 1,000 bootstrap replicates are indicated ( ). The scale bar represents 0.1 expected amino acid residue substitution per site.

). The scale bar represents 0.1 expected amino acid residue substitution per site.

Biochemical characterization of L. pneumophila PDFs.

The genes encoding L. pneumophila PdfA, PdfB, and PdfC were individually cloned into a pET expression vector for overexpression in E. coli. As mentioned previously, there are four possible translation start sites for PdfB. Based on the catalytic motifs of deformylase and the Mws of most characterized PDFs, the fourth start site with an ATG as the initiation codon (the smallest ORF) was chosen to express a 185-amino-acid-residue PdfB protein with a predicted mass of 21 kDa. All L. pneumophila PDFs were highly expressed in E. coli after IPTG induction. Growth at 37°C yielded more than 50% soluble expression of PdfA and PdfC, whereas expression at 17°C was necessary to obtain soluble PdfB. Naturally occurring bacterial PDF uses a ferrous cation to catalyze hydrolysis, but the iron form is highly labile due to oxidation (29, 30). Iron has been replaced by Ni2+ or Co2+ without affecting the catalytic activity but greatly improving stability (16, 28). Therefore, in this case, all three PDFs were purified in the presence of nickel to >95% homogeneity following previously published procedures (33). The identities of the purified proteins were confirmed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis and N-terminal sequencing.

Metal analysis of the PDF enzyme preparations showed that while Ni2+ was the major metal in PdfB, PdfA contained a mixture of Ni2+ and Zn2+ and PdfC contained exclusively Zn2+. To obtain the Ni2+ forms of PdfA and PdfC, both enzymes were expressed in minimal medium with supplemental Ni2+, and a high concentration of Ni2+ was maintained during the purification process. The quantitation of the metal contents of the enzyme preparations used for kinetic analysis is summarized in Table 1. Even though the Ni2+ forms of all the PDFs still had some contamination by Zn2+ (21, 5.6, and 8.5% for PdfA, PdfB, and PdfC, respectively), Ni2+ was the major metal form in the purified PdfA, PdfB, and PdfC (55, 48, and 57%, respectively).

TABLE 1.

Quantitation of metal contents in L. pneumophila PDFs used for kinetic study

| Amt of metala

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni | Zn | Fe | Co | |

| Ni2+ PdfA | 0.55 | 0.21 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Ni2+ PdfB | 0.48 | 0.06 | 0.01 | <0.01 |

| Ni2+ PdfC | 0.57 | 0.09 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Zn2+ PdfA | <0.01 | 0.77 | 0.08 | <0.01 |

| Zn2+ PdfB | <0.03 | 0.88 | 0.14 | <0.01 |

| Zn2+ PdfC | 0.01 | 0.90 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

The amount of metal is given as moles of metal per mole of enzyme.

The purified Ni2+ forms of L. pneumophila PdfA, PdfB, and PdfC were tested for enzymatic activity using three peptide substrates, fMA, fMAS, and fMAKY (Table 2). Ni2+ PdfA displayed higher catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) with longer substrates: fMAKY > fMAS > fMA. The increase in catalytic efficiency using fMAKY as opposed to fMAS as a substrate was the result of both an increase in kcat and a decrease in Km.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of kcat/Km for L. pneumophila PDFsa

| Enzyme | fMA

|

fMAS

|

fMAKY

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km (mM) | kcat/Km (M−1 s−1) | Km (mM) | kcat/Km (M−1 s−1) | Km (mM) | kcat/Km (M−1 s−1) | |

| Ni2+ PdfA | 28 | 3.1 × 103 | 21 | 7.2 × 103 | 7.6 | 2.3 × 104 |

| Ni2+ PdfB | 1.5 | 1.1 × 104 | 0.30 | 7.1 × 104 | 1.3 | 1.3 × 104 |

| Ni2+ PdfC | 0.35 | 4.3 × 104 | 2.4 | 1.4 × 104 | 2.1 | 3.6 × 103 |

| Zn2+ PdfA | 14 | 2.4 × 102 | 20 | 6.5 × 102 | 6.1 | 4.7 × 103 |

| Zn2+ PdfB | 2.7 | 7.9 × 101 | 0.34 | 1.8 × 103 | 1.4 | 1.2 × 102 |

| Zn2+ PdfC | 0.14 | 6.6 × 104 | NAb | 1.7 × 102 | 3.8 | 2.6 × 102 |

All values in the table are the mean of two or more replications with standard deviations typically 15% or less.

NA, no saturation of reaction velocity was observed at the highest concentration of substrate tested.

Ni2+ PdfB had very low activity under the PdfA assay conditions. However, the addition of Ni2+ to the reaction buffer significantly improved the catalytic activity of PdfB. We determined 125 μM NiCl2 to be optimal for PdfB activity. Our current hypothesis is that PdfB has lower affinity toward Ni2+, and therefore, addition of Ni2+ is necessary to maintain the integrity of Ni2+ PdfB upon dilution in the enzymatic assay (final concentration, 6 nM enzyme). In contrast, neither PdfA nor PdfC required additional Ni2+ in the assay buffer for activity, suggesting that both enzymes have high affinity for Ni2+. The preferred substrate for PdfB is fMAS. The increase in catalytic efficiency using fMAS compared to those with fMA and fMAKY can be attributed to the decrease in Km for fMAS.

In the case of Ni2+ PdfC, it favors the shorter substrates fMA and fMAS over fMAKY, as judged by the kcat/Km values. The Km for fMA is 10-fold less than that for fMAS or fMAKY, contributing to the improved catalytic efficiency toward fMA.

Kinetic characterization of the Zn2+ forms of L. pneumophila PdfA, PdfB, and PdfC was also carried out (Tables 1 and 2). As mentioned above, expression of PdfC in rich medium (LB) even in the presence of additional Ni2+ in both the expression and purification steps led to the isolation of the Zn2+ form of PdfC. Presumably, Zn2+ (present in the media or solutions) is very tightly bound to PdfC. In order to isolate the Zn2+ forms of PdfA, it was necessary to strip out the bound Ni2+ using 1,10-phenanthroline from the original mixture of Ni2+ and Zn2+ PdfAs. Similarly, Zn2+ PdfB was also prepared using metal exchange technology (see Materials and Methods). Our kinetic analysis showed that the Zn2+ forms of PdfA and PdfB are significantly less active than the Ni2+ forms, by approximately 10- to 100-fold (Table 2), similar to what has been reported previously for the E. coli Pdf enzyme (16, 30). However, Zn2+ PdfC proved to have activity similar to that of Ni2+ PdfC toward fMA, although it showed different substrate preferences for fMAS and fMAKY. While Zn2+ PdfC favored the shorter substrate fMA over fMAS and fMAKY by >250-fold, kcat/Km values for fMAS and fMAKY were only lower than that for fMA by approximately 3- and 10-fold for Ni2+ PdfC. No saturation in Zn2+ PdfC reaction velocity was observed using fMAS as a substrate.

PDF inhibitors have been reported to have potent activity against L. pneumophila (12). To better understand their mode of antibacterial action in this organism, the inhibition constants of two known PDF inhibitors, actinonin and BB-3497 (6, 8), with MICs of 64 and 1 μg/ml against L. pneumophila Philadelphia 1, respectively, were determined against the three L. pneumophila Ni2+ PDF isozymes and Zn2+ PdfC. We found that both compounds are time-dependent inhibitors (see Materials and Methods) of these isozymes (Table 3). Initial binding constants (Ki) and the overall inhibition constants, Ki*, representing the affinity of the final EI* complex, were determined as described previously (35). As shown in Table 3, both inhibitors exhibited time-dependent inhibition, with their initial binding Ki values in the range of hundreds of nM to 12 μM in the case of actinonin against Ni2+ PdfA. However, the time-dependent inhibition resulted in a significant increase in inhibition potency, and the overall inhibition constants, Ki*, were in the range of 1 to 40 nM for BB-3497 against all three Ni2+-containing isozymes and Zn2+ PdfC. In contrast, actinonin was about 10-fold less potent against PdfA, albeit having similar potencies against Ni2+ PdfB and PdfC. Correlating with this decrease in PdfA potency, there was a 64-fold increase in the MIC for actinonin relative to BB-3497. Thus, it appears that the L. pneumophila MIC might correlate better with the potency against PdfA. Both actinonin and BB-3497 were 10- to 40-fold less potent against Ni2+ PdfC than Zn2+ PdfC, but the significance of this observation is not yet clear.

TABLE 3.

Inhibition of L. pneumophila PDFs by actinonin and BB-3497a

| Isozyme | Actinonin

|

BB-3497

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ki (nM) | Ki* (nM) | Ki (nM) | Ki* (nM) | |

| Ni2+ PdfA | 12,000 ± 2,700 | 330 ± 16 | 940 ± 85 | 44 ± 2 |

| Ni2+ PdfB | 150 ± 44 | 2.3 ± 1.1 | 203 ± 42 | 2.5 ± 0.8 |

| Ni2+ PdfC | 580 ± 91 | 19 ± 2 | 1,600 ± 260 | 43 ± 8 |

| Zn2+ PdfC | 281 ± 11 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 140 ± 22 | 1.1 ± 0.3 |

Ki and Ki* values are the arithmetic means of two or three replicates ± the standard deviation of the mean.

DISCUSSION

Our studies revealed the presence of three pdf genes in the genome of L. pneumophila. Moreover, all three genes have been cloned, and their encoded proteins were expressed, purified, and demonstrated to be enzymatically functional polypeptide deformylases. Although it is not unusual to have more than one pdf gene sequence in a bacterial genome, typically most human pathogens, such as S. aureus, S. pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis, contain only one active pdf gene sequence, while others, like Enterococcus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, contain two. However, L. pneumophila is the first pathogenic bacterium that has been proven to contain three functional pdf genes.

Phylogenetic analysis showed that L. pneumophila PdfA is most closely related to other γ-proteobacterial PDFs encoded by the gene def, consistent with L. pneumophila being a gram-negative bacterium of the γ-proteobacterial lineage. However, PdfB and PdfC are more divergent groups, and their evolutionary origins are unclear. Although several other bacterial species have multiple PDFs, the evolutionary origins of these gene duplications are highly variable. For example, two PDFs in Rickettsia sp. evolved from an apparently recent gene duplication within the genus, while a third copy is highly divergent and falls in a node shared (but weakly supported) with L. pneumophila PdfB and PdfC. Thus, the high divergence of L. pneumophila PdfA relative to PdfB and PdfC is not an uncommon pattern for species with multiple pdf genes.

Genomic analysis of three different geographic isolates of L. pneumophila showed that pdf ORFs are highly conserved in both occurrence and genomic context, suggesting that all three pdf genes are common to L. pneumophila. However, we found that PdfA is identical at the amino acid level among all three L. pneumophila strains, while PdfB and PdfC show slight variation between the strains. Phylogenetic analysis does not support any consistent clustering of strains among these two proteins. In the PdfB node of the tree, L. pneumophila strains Philadelphia 1 and Paris are most closely related, while in the PdfC node, L. pneumophila strains Lens and Philadelphia 1 cluster together. The lower level of intraspecific sequence conservation among PdfB and PdfC relative to PdfA might reflect relaxed selection constraints on these two isoforms. However, comparisons of synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution rates between L. pneumophila strains for individual pdf genes using the PAML software (36) did not reveal any statistical evidence for positive selection (Heather Madsen, personal communication). Overall, phylogenetic analysis suggests that pdfA is the most likely of the three L. pneumophila pdf genes to be the evolutionary and functional orthologue of other bacterial def genes. In addition, pdfA is similarly linked with the fmt gene in the L. pneumophila chromosome.

It is surprising that L. pneumophila contains three PDFs that are quite divergent from each other and yet PDF inhibitors with potent anti-L. pneumophila activity have been reported (12). Here, we have provided strong evidence that PDF is the molecular target of PDF inhibitors, particularly BB-3497, with anti-L. pneumophila activity. As described for other bacterial species (35), both actinonin and BB-3497 exhibit time-dependent inhibition of all three L. pneumophila PDFs, with slow rates of dissociation from the enzymes. While the structural basis for time dependency is undefined at present, it is clear that the net effect of this time-dependent process is a significant potency increase ranging from 20- to 160-fold, comparing Ki to Ki*. Although neither of these two molecules is suitable for use as an anti-infective, similar time-dependent inhibitors with drug-like characteristics might prove useful in the treatment of legionellosis. In addition, weak in vitro activity against L. pneumophila seems to correlate with lower potency against PdfA when PdfB and PdfC are more potently inhibited, although efflux/less penetration could also account for the high MIC observed for actinonin. However, with the genetic essentiality unknown, anti-Legionella agents would likely need to inhibit all three PDFs to provide effective treatment.

The question remains as to why L. pneumophila requires three functional PDFs. In nature, the organism replicates exclusively intracellularly as a parasite of protozoa or as a pathogen of human alveolar macrophages, but it can also survive in water as a free-living microbe. Therefore, it must adapt to extreme fluctuations in its environment, tolerating a range of temperatures, osmolarity, nutrient availability, and other stresses. In fact, it has been shown that there are dramatic phenotypic changes as L. pneumophila enters stationary phase, associated with the expression of a number of traits that allow the bacterium to survive while trying to establish a new replicative niche (24). The three Ni2+ PDF isozymes characterized here display different substrate specificities, and their catalytic efficiencies are appreciably lower than those reported for other bacterial enzymes (33). Perhaps in this organism three enzymes are required to process a wide variety of substrates efficiently. Alternatively, the proteins might be expressed at different stages in the cellular life cycle or in response to specific environmental pressures. Kinetic analysis of both the Ni2+ and Zn2+ forms of L. pneumophila PdfA, PdfB, and PdfC shows that the Zn2+ forms of PdfA and PdfB are significantly less active than their Ni2+ counterparts (Ni2+ is the surrogate metal for Fe2+), suggesting that it is likely that PdfA and PdfB have Fe2+ as the physiologically relevant metal. However, Zn2+ PdfC has activity toward the fMA substrate comparable to that of Ni2+ PdfC, although the substrate preference profile is different among the three peptides tested. There is an intriguing possibility that the Zn2+ form of PdfC may be relevant under specific conditions during the life cycle of L. pneumophila.

More experiments are required to investigate the expression of the three PDFs in L. pneumophila and the role of Zn2+ versus Fe2+ for PdfC at different stages in the life cycle and under diverse environmental conditions. Furthermore, genetic knockout experiments should be carried out to unravel which PDF or PDFs play an essential role in L. pneumophila growth and in establishing and maintaining infection in humans.

Acknowledgments

We thank John Broskey for providing L. pneumophila strain Philadelphia 1 and for MIC determinations, Wendy S. Halsey and Elizabeth S. Thomas for DNA sequencing, Komal Jain and Heather Madsen for bioinformatics assistance, and Peter Tummino and Robert A. Copeland for helpful discussions. We thank David J. Payne for his support and encouragement with this project and for critical reading and comments on the manuscript.

J.R.B. acknowledges the support of Bioinformatics, Genetics Research, GlaxoSmithKline.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boularot, A., C. Giglione, I. Artaud, and T. Meinnel. 2004. Structure-activity relationship analysis and therapeutic potential of peptide deformylase inhibitors. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 5:809-822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brenner, D. J., A. Steigerwalt, J. E. Weaver, J. E. McDade, J. C. Feeley, and M. Mandel. 1978. Classification of the Legionnaires' disease bacterium: an interim report. Curr. Microbiol. 1:71-75. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cazalet, C., C. Rusniok, H. Bruggemann, N. Zidane, A. Magnier, L. Ma, M. Tichit, S. Jarraud, C. Bouchier, F. Vandenesch, F. Kunst, J. Etienne, P. Glaser, and C. Buchrieser. 2004. Evidence in the Legionella pneumophila genome for exploitation of host cell functions and high genome plasticity. Nat. Genet. 36:1165-1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan, P. F., K. M. O'Dwyer, L. M. Palmer, J. D. Ambrad, K. A. Ingraham, C. So, M. A. Lonetto, S. Biswas, M. Rosenberg, D. J. Holmes, and M. Zalacain. 2003. Characterization of a novel fucose-regulated promoter (PfcsK) suitable for gene essentiality and antibacterial mode-of-action studies in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 185:2051-2058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, D. Z., D. V. Patel, C. J. Hackbarth, W. Wang, G. Dreyer, D. C. Young, P. S. Margolis, C. Wu, Z. J. Ni, J. Trias, R. J. White, and Z. Yuan. 2000. Actinonin, a naturally occurring antibacterial agent, is a potent deformylase inhibitor. Biochemistry 39:1256-1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chien, M., I. Morozova, S. Shi, H. Sheng, J. Chen, S. M. Gomez, G. Asamani, K. Hill, J. Nuara, M. Feder, J. Rineer, J. J. Greenberg, V. Steshenko, S. H. Park, B. Zhao, E. Teplitskaya, J. R. Edwards, S. Pampou, A. Georghiou, I. C. Chou, W. Iannuccilli, M. E. Ulz, D. H. Kim, A. Geringer-Sameth, C. Goldsberry, P. Morozov, S. G. Fischer, G. Segal, X. Qu, A. Rzhetsky, P. Zhang, E. Cayanis, P. J. De Jong, J. Ju, S. Kalachikov, H. A. Shuman, and J. J. Russo. 2004. The genomic sequence of the accidental pathogen Legionella pneumophila. Science 305:1966-1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clements, J. M., R. P. Beckett, A. Brown, G. Catlin, M. Lobell, S. Palan, W. Thomas, M. Whittaker, S. Wood, S. Salama, P. J. Baker, H. F. Rodgers, V. Barynin, D. W. Rice, and M. G. Hunter. 2001. Antibiotic activity and characterization of BB-3497, a novel peptide deformylase inhibitor. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:563-570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edelstein, P. H., and R. D. Meyer. 1984. Legionnaires' disease. A review. Chest 85:114-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Felsenstein, J. 2000. PHYLIP (Phylogenetic Inference Package) 3.6. University of Washington, Seattle.

- 11.Fields, B. S., R. F. Benson, and R. E. Besser. 2002. Legionella and Legionnaires' disease: 25 years of investigation. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:506-526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fritsche, T. R., H. S. Sader, R. Cleeland, and R. N. Jones. 2005. Comparative antimicrobial characterization of LBM415 (NVP PDF-713), a new peptide deformylase inhibitor of clinical importance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:1468-1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giglione, C., and T. Meinnel. 2001. Organellar peptide deformylases: universality of the N-terminal methionine cleavage mechanism. Trends Plant Sci. 6:566-572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giglione, C., M. Pierre, and T. Meinnel. 2000. Peptide deformylase as a target for new generation, broad spectrum antimicrobial agents. Mol. Microbiol. 36:1197-1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grant, S. K., B. G. Green, and J. W. Kozarich. 2001. Inhibition and structure-activity studies of methionine hydroxamic acid derivatives with bacterial peptide deformylase. Bioorg. Chem. 29:211-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Groche, D., A. Becker, I. Schlichting, W. Kabsch, S. Schultz, and A. F. Wagner. 1998. Isolation and crystallization of functionally competent Escherichia coli peptide deformylase forms containing either iron or nickel in the active site. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 246:342-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gross, M., J. Clements, R. P. Beckett, W. Thomas, S. Taylor, D. Lofland, S. Ramanathan-Girish, M. Garcia, S. Difuntorum, U. Hoch, H. Chen, and K. W. Johnson. 2004. Oral anti-pneumococcal activity and pharmacokinetic profiling of a novel peptide deformylase inhibitor. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 53:487-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guilloteau, J. P., M. Mathieu, C. Giglione, V. Blanc, A. Dupuy, M. Chevrier, P. Gil, A. Famechon, T. Meinnel, and V. Mikol. 2002. The crystal structures of four peptide deformylases bound to the antibiotic actinonin reveal two distinct types: a platform for the structure-based design of antibacterial agents. J. Mol. Biol. 320:951-962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones, R. N., T. R. Fritsche, and H. S. Sader. 2004. Antimicrobial spectrum and activity of NVP PDF-713, a novel peptide deformylase inhibitor, tested against 1,837 recent Gram-positive clinical isolates. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 49:63-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lazennec, C., and T. Meinnel. 1997. Formate dehydrogenase-coupled spectrophotometric assay of peptide deformylase. Anal. Biochem. 244:180-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lofland, D., S. Difuntorum, A. Waller, J. M. Clements, M. K. Weaver, J. A. Karlowsky, and K. Johnson. 2004. In vitro antibacterial activity of the peptide deformylase inhibitor BB-83698. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 53:664-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Margolis, P. S., C. J. Hackbarth, D. C. Young, W. Wang, D. Chen, Z. Yuan, R. White, and J. Trias. 2000. Peptide deformylase in Staphylococcus aureus: resistance to inhibition is mediated by mutations in the formyltransferase gene. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1825-1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meinnel, T., C. Lazennec, S. Villoing, and S. Blanquet. 1997. Structure-function relationships within the peptide deformylase family. Evidence for a conserved architecture of the active site involving three conserved motifs and a metal ion. J. Mol. Biol. 4:749-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Molofsky, A. B., and M. S. Swanson. 2004. Differentiate to thrive: lessons from the Legionella pneumophila life cycle. Mol. Microbiol. 53:29-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nguyen, K. T., X. Hu, C. Colton, R. Chakrabarti, M. X. Zhu, and D. Pei. 2003. Characterization of a human peptide deformylase: implications for antibacterial drug design. Biochemistry 42:9952-9958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nguyen, K. T., X. Hu, and D. Pei. 2004. Slow-binding inhibition of peptide deformylase by cyclic peptidomimetics as revealed by a new spectrophotometric assay. Bioorg. Chem. 32:178-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Page, R. D. 1996. TreeView: an application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 12:357-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ragusa, S., S. Blanquet, and T. Meinnel. 1998. Control of peptide deformylase activity by metal cations. J. Mol. Biol. 280:515-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rajagopalan, P. T., and D. Pei. 1998. Oxygen-mediated inactivation of peptide deformylase. J. Biol. Chem. 273:22305-22310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rajagopalan, P. T., X. Yu, and D. Pei. 1997. Peptide deformylase: a new type of mononuclear iron protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119:12418-12419. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning, a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 32.Serero, A., C. Giglione, A. Sardini, J. Martinez-Sanz, and T. Meinnel. 2003. An unusual peptide deformylase features in the human mitochondrial N-terminal methionine excision pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 278:52953-52963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith, K. J., C. M. Petit, K. Aubart, M. Smyth, E. McManus, J. Jones, A. Fosberry, C. Lewis, M. Lonetto, and S. B. Christensen. 2003. Structural variation and inhibitor binding in polypeptide deformylase from four different bacterial species. Protein Sci. 12:349-360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Aller, G. S., R. Nandigama, C. M. Petit, W. E. DeWolf, Jr., C. J. Quinn, K. M. Aubart, M. Zalacain, S. B. Christensen, R. A. Copeland, and Z. Lai. 2005. Mechanism of time-dependent inhibition of polypeptide deformylase by actinonin. Biochemistry 44:253-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang, Z. 1997. PAML: a program package for phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 13:555-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yuan, Z., J. Trias, and R. J. White. 2001. Deformylase as a novel antibacterial target. Drug Discov. Today 6:954-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]