Abstract

We have sequenced fragments of five metabolic housekeeping genes and two genes encoding outer membrane proteins from 81 isolates of Francisella tularensis, representing all four subspecies. Phylogenetic clustering of gene sequences from F. tularensis subsp. tularensis and F. tularensis subsp. holarctica aligned well with subspecies affiliations. In contrast, F. tularensis subsp. novicida and F. tularensis subsp. mediasiatica were indicated to be phylogenetically incoherent taxa. Incongruent gene trees and mosaic structures of housekeeping genes provided evidence for genetic recombination in F. tularensis.

Francisella tularensis is a facultative intracellular bacterium and the causative agent of tularemia, a zoonosis affecting a great variety of vertebrate species. Due to its highly infectious nature and its ability to cause severe disease in humans, F. tularensis in the past was explored as a potential biological warfare agent in military research programs in the United States, Japan, and the former Soviet Union (5). Recently, F. tularensis has been listed among the top six potential bioterrorism agents (22).

Four subspecies of F. tularensis are currently recognized (23). F. tularensis subsp. tularensis (also termed “type A”) encompasses those isolates most virulent to humans. F. tularensis subsp. holarctica (“type B”) is also highly infectious but rarely fatal in cases of human infection. Several strains of F. tularensis subsp. mediasiatica have been collected in central Asia, but little is known about their characteristics. F. tularensis subsp. novicida rarely causes disease in humans. It is the only subspecies of F. tularensis evidently not confined to the Northern Hemisphere, as it was recently reported in Australia (29).

Despite distinct variations in virulence and different geographic origins, isolates of F. tularensis display little genetic variation. Subspecies are closely related phylogenetically. The most efficient strain discrimination reported to date was achieved by PCR analyses of size polymorphisms of short-sequence tandem repeats in the genome of F. tularensis (variable-number tandem repeat analysis [VNTR]) (6, 7, 11, 12). A recent study revealed two genetically distinct clusters among isolates of F. tularensis subsp. tularensis and several clusters within F. tularensis subsp. holarctica (11). Analysis of the most-variable locus, a 9-bp repeat, provided 31 length variants (alleles) among 192 strains (11). In addition, pronounced linkage among alleles at different VNTR loci suggested a clonal population structure (11).

However, while highly variable short sequence repeats permit the currently most discriminatory typing procedure for Francisella tularensis, sequences from genes encoding proteins may be less prone to repeated mutations, in the absence of selection, and hence provide a more reliable phylogenetic signal (9, 14). In addition, typing results based on DNA sequencing are more portable between laboratories (24). In this study, we have investigated the genetic population structure of F. tularensis on the basis of nucleotide sequences from five housekeeping genes (tpiA, dnaA, mutS, prfB, and putA) and two genes encoding membrane proteins (tul4 and fopA) that had been exploited for PCR-based species identification in the past.

Sequence analyses.

Bacterial isolates investigated in this study are listed in Table 1. Oligonucleotide primers for PCR were designed on the basis of genome sequences available from F. tularensis strains Schu S4 (subspecies tularensis; sequence accession no. AJ749949) and LVS (subspecies holarctica; preliminary sequence data available at http://bbrp.llnl.gov). Primer sequences are posted in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The seven loci investigated are located at physically distant positions on the bacterial chromosome as judged from the genome sequence from strain Schu S4 (Table 2). PCR and sequence analyses of both strands of the PCR products were performed by standard procedures. Sequences were deposited in the EMBL sequence database. Sequence divergence within F. tularensis (Table 2) was based on single-nucleotide polymorphisms rather than insertions or deletions. The ratio of mean nonsynonymous to synonymous substitutions per site (dN/dS), calculated with the software START (13), varied from 0.066 (dnaA) to 0.242 (tul4), indicating strong purifying selection (Table 2) acting on all loci investigated, including the genes encoding membrane proteins (tul4 and fopA). Sequences from locus fopA, however, were unusually uniform (Table 2). Different sequences at the five housekeeping loci resulted in 13 different allelic profiles or sequence types (ST1 to ST13) (Table 3). When the two loci encoding membrane proteins (tul4 and fopA) were included in the analysis, three additional sequence types were detected (ST14 to ST16).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strainsa

| Species and origin | Strain | Alternative designation | Length (bp) of indicated fragment

|

Sequence type | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ft-M10 | Ft-M3 | RD1 | ||||

| F. tularensis subsp. holarctica | ||||||

| Live vaccine strain, Russia | ATCC 29684 | 361 | 351 | 924 | ST2 | |

| Wild rabbit, Bulgaria, 1998 | F80 | RKI 03-1289, L1 | 361 | 351 | 924 | ST2 |

| Water animal, Bulgaria, 1962 | F81 | RKI 03-1292, Srebarna 19 | 361 | 351 | 924 | ST2 |

| United States | F82 | RKI 03-1293, Kodar R | 361 | 351 | 924 | ST2 |

| Russia, 1965 | F76 | RKI 03-1294, Kosho | 361 | 306 | 924 | ST6 |

| United States | F83 | RKI 03-1295, Tun Fac | 361 | 396 | 924 | ST16 |

| Russia | F84 | RKI 03-1297, Gaiski 15 | 361 | 351 | 924 | ST2 |

| United States, 1959 | F85 | RKI 03-1298, O-284 | 361 | 297 | 924 | ST6 |

| United States | F86 | RKI 03-1299, O-363 | 361 | 378 | 924 | ST15 |

| United States, 1958 | F77 | RKI 03-1302, KF479 | 361 | 306 | 924 | ST6 |

| Hare, France, 1952 | F78 | RKI 03-1303, Chateauroux | 361 | 423 | 924 | ST2 |

| Origin unknown | F1 | BGA | 361 | 297 | 924 | ST6 |

| Human, Austria (Mistelbach), 1997 | F2 | 361 | 297 | 924 | ST2 | |

| Human, Austria (Wien), 1997 | F11 | 361 | 306 | 924 | ST2 | |

| Human, Austria (Horn), 1997 | F36 | 361 | 306 | 924 | ST2 | |

| Hare, Austria, 1994 (6 isolates) | F6, F7, F53-F56 | 361 | 297-324 | 924 | ST2 | |

| Hare, Austria, 1995 (2 isolates) | F8, F57 | 361 | 306 | 924 | ST2 | |

| Hare, Austria, 1996 (2 isolates) | F9, F10 | 361 | 306 | 924 | ST2 | |

| Hare, Austria, 1997 (31 isolates) | F3-F41 | 361 | 297-324 | 924 | ST2 | |

| Hare, Austria, 1997 (1 isolate) | F28 | 361 | 306 | 924 | ST14 | |

| Hare, Austria, 1997 (1 isolate) | F30 | 361 | 342 | 924 | ST7 | |

| Hare, Austria, 1998 (5 isolates) | F42-F47 | 361 | 297-351 | 924 | ST2 | |

| F. tularensis subsp. tularensis | ||||||

| Human, Ohio, 1941 | Schu S4 | 617 | 432 | 1,522 | ST1 | |

| Human, Utah, 1920 | F66 | ATCC 6223 | 345 | 279 | 1,522 | ST4 |

| United States, 1959 | F87 | RKI 03-1300, 8859 | 345 | 306 | 1,522 | ST5 |

| Squirrel, Georgia | FSC033 | SnMF, “CDC standard” | 425 | 360 | 1,522 | ST1 |

| Tick, British Columbia, 1935 | FSC041 | Vavenby | 489 | 378 | 1,522 | ST1 |

| Canada | FSC042 | Utter | 345 | 279 | 1,522 | ST5 |

| Human, Ohio, 1941 | FSC043 | Schu | 617 | 432 | 1,522 | ST1 |

| Hare, Nevada, 1953 | FSC054 | Nevada 14 | 351 | 345 | 1,522 | ST5 |

| F. tularensis subsp. mediasiatica | ||||||

| Miday gerbil, Kazakhstan, 1965 | F63 | FSC147, 543 | 361 | 450 | 1,453 | ST10 |

| Tick, central Asia, 1982 | F64 | FSC148, 240 | 361 | 432 | 1,453 | ST11 |

| Hare, central Asia, 1965 | F65 | FSC149, 120 | 361 | 450 | 1,453 | ST12 |

| F. tularensis subsp. novicida | ||||||

| Water, Utah, 1950 | ATCC 15482 | NA | 486 | 3,300 | ST3 | |

| Water, United States, 1950 | F79 | RKI 03-1304 | NA | 486 | 3,300 | ST3 |

| Human, Texas, 1991 | F59 | FSC156, Fx1 | NA | 585 | NA | ST8 |

| Human, Texas, 1995 | F60 | FSC159, Fx2 | NA | 585 | 3,000 | ST9 |

| Water, Utah, 1950 | F61 | FSC040 | NA | 486 | 3,300 | ST3 |

| Spain | F62 | FSC454 | NA | NA | NA | ST13 |

| F. philomiragiab | ||||||

| Muskrat, Utah, 1959 | DSM 7535 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Water, Utah | F50 | ATCC 25016 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Muskrat, Utah, 1959 | F51 | ATCC 25015 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Water, Utah | F93 | ATCC 25017 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Water, Utah | F94 | ATCC 25018 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

NA, no amplification.

From F. philomiragia, only tpiA, prfB, and fopA could be amplified and sequenced.

TABLE 2.

Genomic positions of the seven loci and sequence variation within F. tularensis

| Gene | Genomic positiona | Sequence length (bp) | No. of alleles | Maximum sequence divergence (%) | dN/dS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dnaA | 370 | 471 | 12 | 7.0 | 0.066 |

| tpiA | 83715 | 417 | 9 | 6.0 | 0.155 |

| prfB | 207710 | 304 | 7 | 9.9 | 0.083 |

| fopA | 599187 | 467 | 8 | 1.4 | 0.099 |

| tul4 | 909891 | 314 | 10 | 9.5 | 0.242 |

| putA | 1165439 | 371 | 5 | 7.8 | 0.070 |

| mutS | 1553295 | 411 | 9 | 5.6 | 0.093 |

Within the genome of strain Schu S4 (sequence accession number AJ749949).

TABLE 3.

Allelic profiles

| Sequence type | No. of isolates | Representative strain | Allele no.

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housekeeping genes

|

Membrane protein genes

|

||||||||

| tpiA | dnaA | prfB | mutS | putA | tul4 | fopA | |||

| ST1 | 4 | Schu S4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| ST2 | 35 | ATCC 29684 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| ST3 | 3 | ATCC 15482 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| ST4 | 1 | F66 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| ST5 | 3 | F87 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| ST6 | 4 | F1 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| ST7 | 1 | F30 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| ST8 | 1 | F59 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| ST9 | 1 | F60 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 6 | 6 |

| ST10 | 1 | F63 | 7 | 9 | 5 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 5 |

| ST11 | 1 | F64 | 7 | 10 | 5 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 5 |

| ST12 | 1 | F65 | 8 | 11 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 7 |

| ST13 | 1 | F62 | 9 | 12 | 7 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 5 |

| ST14 | 1 | F28 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 2 |

| ST15 | 1 | F83 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 8 |

| ST16 | 1 | F86 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

Evidence for homologous genetic recombination.

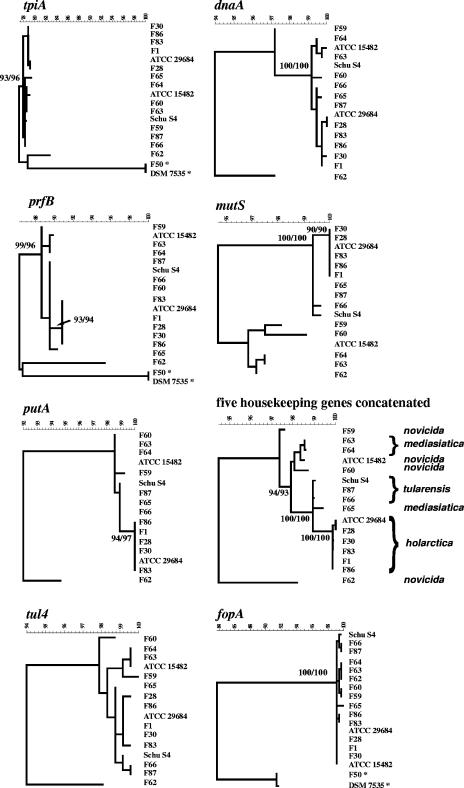

Phylogenetic trees based on different genes are incongruent (Fig. 1). Several isolates of F. tularensis subsp. novicida (F59, F60, and F62) show different phylogenetic affiliations depending on the gene considered (Fig. 1). For example, and most obviously, based on four of the seven genes investigated, isolate F62 branches off deeply from the F. tularensis clade, with strong bootstrap support and pairwise sequence differences of up to 9.2%, while it clusters together significantly with isolate F59 in the dnaA tree and has fopA and mutS sequences that are identical or nearly so (one nucleotide difference) to those from isolates ATCC 15482 and F. tularensis subsp. mediasiatica F63 and F64 (Fig. 1). Discordances between sequence data from different loci were evaluated by utilizing the incongruence length difference test implemented in PAUP 4b10. Results are indicated in Table S2 in the supplemental material. For four gene combinations (dnaA-mutS, dnaA-tul4, dnaA-fopA, and tpiA-fopA), significant conflict between data sets was indicated by P values below the recommended threshold of 0.05 (4, 8, 15). When strains F59, F60, and F62 were excluded from these analyses, all P values were above 0.05 (not shown).

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic trees based on gene sequences as indicated and calculated by using the maximum likelihood algorithm in the BIONUMERICS software package, version 4.0 (Applied Maths). One representative isolate from each sequence type (Table 3) was included in the computations. When available, gene sequences from Francisella philomiragia isolates (indicated by asterisks) were included as outgroups to enable bootstrap analyses of the deepest nodes within the F. tularensis clade. Bootstrap values from 100 resamplings are indicated when they are at least 90%. They are based on both the maximum-parsimony and neighbor-joining algorithms and were computed by using PHYLIP 3.65. Subspecies affiliations are indicated in the tree based on concatenated gene sequences. Scale bars indicate percent sequence similarity.

To identify mosaic genes generated through recombination, we utilized both phylogenetic and nucleotide substitution distribution methods (20). The likelihood method of Grassly and Holmes (10), which is implemented in the software PLATO, indicated the presence of anomalously evolving regions that do not fit with a respective single phylogenetic topology in sequences from tpiA, dnaA, prfB, and mutS (Bonferroni-corrected significance level [α], 0.05). Reinvestigations allowing gamma-distributed evolution rate heterogeneity (four rate categories; shape parameter, 0.1) and altered transition/transversion ratios (range, 0.5 to 2.05) did not change these results for dnaA, prfB, and mutS, affirming recombination to be the underlying evolutionary cause for phylogenetic discordance rather than spatial variation of the evolution rate or selective pressure along the sequences (10). Predicted recombinational breakpoints in these sequences are indicated in Table 4. For tpiA, in contrast, a higher transition/transversion ratio suggested a locally increased negative, conservative, selective pressure (since transitions are more likely to be synonymous changes [10]).

TABLE 4.

Mosaic gene structures

| Recombinant sequence

|

Breakpoint(s) predicted by:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Isolatea | MAXCHIb | PLATOc |

| prfB | F62 | 152 | 152 |

| dnaA | F62 | 40 | 48 |

| mutS | F59 | 65, 143, 330 | 58, 136, 323 |

Isolate in which the respective recombinant sequence was detected by MAXCHI.

MAXCHI is an implementation of the maximum chi-square method in RDP, version 2.0. Sequence pairs were scanned, and the window size was set at 30 variable sites. With multiple-comparison correction turned off, the highest acceptable probability that potentially recombinant regions shared identity by mere chance was set at 0.001 (P < 0.001).

Input maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees for PLATO were computed by using DNAML implemented in PHYLIP 3.65. Bonferroni-corrected significance level (α), 0.05.

Application of the maximum chi-square method (17), which is implemented in RDP, version 2.0 (16), confirmed the inferred mosaic structures of the genes dnaA, prfB, and mutS in F. tularensis subsp. novicida isolates F59 and F62 (P < 0.001) and predicted recombinational breakpoints in these sequences similar to those predicted by PLATO (Table 4).

The homoplasy test (implemented in the START software package [13]) was used to relate the frequency of observed synonymous homoplasies (that is, the same nucleotide changes in different branches of a maximum-parsimony tree) in the concatenated sequences from F. tularensis to the frequency expected under free recombination (18). Depending on the conservative consideration of potential very high or medium-high codon usage bias (18), respectively, this homoplasy ratio was calculated to be 0.09 to 0.10, which is low in comparison to several other bacterial species (26), suggesting that the overall contribution of recombination to the observed sequence variation is limited. However, the probability that the observed homoplasies could not be explained by mutations alone (and hence required recombination) was indicated to be 95% to 99% (18).

In conclusion, we have found several lines of evidence for limited horizontal genetic transfer and recombination in F. tularensis. No evidence was found, however, for recombination events in F. tularensis subsp. tularensis and F. tularensis subsp. holarctica. Rather, mosaic genes were discovered in F. tularensis subsp. novicida exclusively, and, in fact, omission of isolates F59, F60, and F62 from phylogenetic analyses eliminated the discrepancies among gene trees detected by incongruence length difference testing. These results are consistent with an underlying population in which recombination may be common and from which more-virulent clones that dominate medical interest and culture collections today have emerged and become widespread. Such a population structure previously has been termed “epidemic” (19). Consistently, based on gene content, F. tularensis subsp. novicida was recently concluded to be evolutionarily the oldest subspecies (27). Alternatively, recombination may be more frequent in, or restricted to, F. tularensis subsp. novicida. Our findings do not contradict the recently reported linkage disequilibrium among VNTR loci of this species, since only 2% of the isolates investigated in that study were affiliated with F. tularensis subsp. novicida (11). Currently, the genomes from several F. tularensis isolates are being sequenced (see www.genomesonline.org); those projects will provide abundant data for investigating the extent of recombination in these bacteria.

Phylogenetic diversity.

Despite the detected signatures of recombinational events, the gene trees are far more similar than would be expected by chance alone (Fig. 1; also see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Hence, the extent of recombination in F. tularensis is not sufficient to completely obliterate the phylogenetic signal in the gene sequences. We therefore prefer to calculate phylogenetic relationships among the isolates on the basis of concatenated nucleotide sequences rather than allelic profiles, because the latter do not consider the extent of sequence difference (21, 24).

For F. tularensis subsp. holarctica and F. tularensis subsp. tularensis, results of phylogenetic analyses based on concatenated nucleotide sequences correlate very well with RD1 amplification fragment lengths and VNTR data, notably the amplification fragment sizes from the 16-bp repeat locus termed Ft-M10 (Fig. 1, Table 1); analyses of RD1 fragments and the short sequence repeats Ft-M3 and Ft-M10 were performed as described previously (3, 12). The sizes of both amplification fragments, RD1 and Ft-M10 (also termed SSTR16 or Ft-V2 [6, 11, 12]), have previously been reported to be conserved in each of these two subspecies (3, 6, 11, 12). Hence, we conclude that our sequence data confirm these two subspecies each to be monophyletic entities.

Isolates of F. tularensis subsp. holarctica display little genetic diversity, with the majority assigned to two genotypes (ST2 and ST6) and a few single-locus and double-locus variants of these. Generally, Ft-M3 fragment lengths from F. tularensis subsp. holarctica were found to be more variable than our allelic profiles. However, in several cases, isolates affiliated with different sequence types had Ft-M3 fragments of identical lengths. Remarkably, sequence types ST2 and ST6 differ at two housekeeping loci (tpiA and dnaA) and, on this basis, would not be considered particularly closely related (9) (Table 3). Even so, several isolates of both sequence types have Ft-M3 fragment lengths of 297 bp (for example, isolates F1 and F2) and 306 bp (for example, isolates F77 and F8 [Table 1]). We conclude that these identical Ft-M3 fragment lengths are homoplastic and provide misleading information about the isolates' phylogenetic relationships.

Isolates of F. tularensis subsp. tularensis form two separate phylogenetic clusters which likely correspond to the two distinct groups A.I (includes Schu S4) and A.II (includes ATCC 6223/F66) that were recently discovered on the basis of VNTR analyses (11). Definitive correlation with VNTR groups A.I and A.II cannot be confirmed at present, however, because the corresponding VNTR fragment lengths were not published in that previous report (11). One of the F. tularensis subsp. tularensis isolates, F87, has an Ft-M3 fragment of 306 bp which is not homologous to the same fragment in several sequence types (ST2, ST6, and ST14) among F. tularensis subsp. holarctica isolates. Nucleotide sequences of Ft-M3 fragments from the two subspecies differ by 5.5%.

Previously, restriction fragment length polymorphism analyses and genome comparisons through DNA microarray hybridization led to the conclusion that the subspecies F. tularensis subsp. holarctica and F. tularensis subsp. tularensis are highly homogeneous genetically (3, 28). While our data do not contradict these results, it should be considered that, even based on our limited data set, each of these subspecies appears to be more diverse than several highly uniform pathogens, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Bacillus anthracis, and Yersinia pestis (2, 21, 25). Hence, both subspecies of F. tularensis are likely to be significantly older than any of these recently emerged species (1).

Francisella tularensis subsp. novicida was indicated to be paraphyletic, as it does not include F. tularensis subsp. mediasiatica isolates F63 and F64, which descend from the same common ancestor (Fig. 1). Moreover, the three isolates assigned to F. tularensis subsp. mediasiatica did not form a single cluster, and F65 did not appear to be particularly related to F63 and F64. Instead, some affinity of F65 to F. tularensis subsp. tularensis may exist, which previously had been suggested for the entire subspecies (3, 11). Obviously, F. tularensis subsp. novicida and F. tularensis subsp. mediasiatica do not form phylogenetically coherent taxonomic entities and possibly should be reclassified. However, these taxonomic problems can be solved only when more isolates of these subspecies become available. Obviously, much of the diversity of F. tularensis extant in nature remains to be discovered.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences determined in this study have been submitted to the EMBL database under accession no. AM 261086 to AM 261205.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge E. Savov (Military Medical Academy, Sofia, Bulgaria) and M. Forsman (Swedish Defense Research Agency, Umeå, Sweden) for providing F. tularensis strains. We thank U. Siewert and W. Streckel for excellent technical assistance, R. Prager for DNA extractions, and A. Tille for informatics support. We are grateful for access to then-unfinished genome sequence data produced by the sequencing consortium deciphering the genome from strain Schu S4 and by the BBRP sequencing group at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Livermore, Calif. (strain LVS). Comments from two anonymous reviewers of an earlier version of the manuscript were highly appreciated.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achtman, M. 2004. Population structure of pathogenic bacteria revisited. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 294:67-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Achtman, M., K. Zurth, G. Morelli, G. Torrea, A. Guiyoule, and E. Carniel. 1999. Yersinia pestis, the cause of plague, is a recently emerged clone of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:14043-14048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Broekhuijsen, M., P. Larsson, A. Johansson, M. Bystrom, U. Eriksson, E. Larsson, R. G. Prior, A. Sjöstedt, R. W. Titball, and M. Forsman. 2003. Genome-wide DNA microarray analysis of Francisella tularensis strains demonstrates extensive genetic conservation within the species but identifies regions that are unique to the highly virulent F. tularensis subsp. tularensis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:2924-2931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown, E. W., M. K. Mammel, J. E. LeClerc, and T. A. Cebula. 2003. Limited boundaries for extensive horizontal gene transfer among Salmonella pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:15676-15681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dennis, D. T., T. V. Inglesby, D. A. Henderson, J. G. Bartlett, M. S. Ascher, E. Eitzen, A. D. Fine, A. M. Friedlander, J. Hauer, M. Layton, S. R. Lillibridge, J. E. McDade, M. T. Osterholm, T. O'Toole, G. Parker, T. M. Perl, P. K. Russell, and K. Tonat. 2001. Tularemia as a biological weapon: medical and public health management. JAMA 285:2763-2773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farlow, J., K. L. Smith, J. Wong, M. Abrams, M. Lytle, and P. Keim. 2001. Francisella tularensis strain typing using multiple-locus, variable-number tandem repeat analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3186-3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farlow, J., D. M. Wagner, M. Dukerich, M. Stanley, M. Chu, K. Kubota, J. Petersen, and P. Keim. 2005. Francisella tularensis in the United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11:1835-1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farris, J. S., M. Källersjö, A. G. Kluge, and C. Bult. 1995. Constructing a significance test for incongruence. Syst. Biol. 44:570-572. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feil, E. J. 2004. Small change: keeping pace with microevolution. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:483-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grassly, N. C., and E. C. Holmes. 1997. A likelihood method for the detection of selection and recombination using nucleotide sequences. Mol. Biol. Evol. 14:239-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johansson, A., J. Farlow, P. Larsson, M. Dukerich, E. Chambers, M. Bystrom, J. Fox, M. Chu, M. Forsman, A. Sjöstedt, and P. Keim. 2004. Worldwide genetic relationships among Francisella tularensis isolates determined by multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis. J. Bacteriol. 186:5808-5818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johansson, A., I. Goransson, P. Larsson, and A. Sjöstedt. 2001. Extensive allelic variation among Francisella tularensis strains in a short-sequence tandem repeat region. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3140-3146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jolley, K. A., E. J. Feil, M. S. Chan, and M. C. Maiden. 2001. Sequence type analysis and recombinational tests (START). Bioinformatics 17:1230-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keim, P., M. N. Van Ert, T. Pearson, A. J. Vogler, L. Y. Huynh, and D. M. Wagner. 2004. Anthrax molecular epidemiology and forensics: using the appropriate marker for different evolutionary scales. Infect. Genet. Evol. 4:205-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ko, K. S., J. W. Kim, J. M. Kim, W. Kim, S. I. Chung, I. J. Kim, and Y. H. Kook. 2004. Population structure of the Bacillus cereus group as determined by sequence analysis of six housekeeping genes and the plcR gene. Infect. Immun. 72:5253-5261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin, D. P., C. Williamson, and D. Posada. 2005. RDP2: recombination detection and analysis from sequence alignments. Bioinformatics 21:260-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maynard Smith, J. 1992. Analyzing the mosaic structure of genes. J. Mol. Evol. 34:126-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maynard Smith, J., and N. H. Smith. 1998. Detecting recombination from gene trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 15:590-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maynard Smith, J., N. H. Smith, M. O'Rourke, and B. G. Spratt. 1993. How clonal are bacteria? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:4384-4388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Posada, D., and K. A. Crandall. 2001. Evaluation of methods for detecting recombination from DNA sequences: computer simulations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:13757-13762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Priest, F. G., M. Barker, L. W. Baillie, E. C. Holmes, and M. C. Maiden. 2004. Population structure and evolution of the Bacillus cereus group. J. Bacteriol. 186:7959-7970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rotz, L. D., A. S. Khan, S. R. Lillibridge, S. M. Ostroff, and J. M. Hughes. 2002. Public health assessment of potential biological terrorism agents. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:225-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sjöstedt, A. 2005. Francisella, p. 200-210. In D. J. Brenner, N. R. Kreig, J. T. Staley, and G. M. Garrity (ed.), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, vol. 2, part B. Springer, New York, N.Y. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spratt, B. G. 1999. Multilocus sequence typing: molecular typing of bacterial pathogens in an era of rapid DNA sequencing and the internet. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:312-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sreevatsan, S., X. Pan, K. Stockbauer, N. D. Connell, B. N. Kreiswirth, T. S. Whittam, and J. M. Musser. 1997. Restricted structural gene polymorphism in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex indicates evolutionarily recent global dissemination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:9869-9874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suerbaum, S., and M. Achtman. 1999. Evolution of Helicobacter pylori: the role of recombination. Trends Microbiol. 7:182-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Svensson, K., P. Larsson, D. Johansson, M. Bystrom, M. Forsman, and A. Johansson. 2005. Evolution of subspecies of Francisella tularensis. J. Bacteriol. 187:3903-3908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomas, R., A. Johansson, B. Neeson, K. Isherwood, A. Sjöstedt, J. Ellis, and R. W. Titball. 2003. Discrimination of human pathogenic subspecies of Francisella tularensis by using restriction fragment length polymorphism. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:50-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whipp, M. J., J. M. Davis, G. Lum, J. de Boer, Y. Zhou, S. W. Bearden, J. M. Petersen, M. C. Chu, and G. Hogg. 2003. Characterization of a novicida-like subspecies of Francisella tularensis isolated in Australia. J. Med. Microbiol. 52:839-842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.