Abstract

Transcription of both chromosomal and extrachromosomally introduced nifS was regulated (up-expressed) by oxygen or by supplemental iron conditions. This up-expression was not observed in a fur mutant strain background or when an iron chelator was added. Iron-bound Fur (but not apo-Fur) recognized the nifS promoter, and Fur bound significantly farther upstream (−155 bp to −190 bp and −210 to −240 bp) in the promoter than documented Helicobacter pylori Fur binding regions. This binding was stronger than Fur recognition of the flgE or napA promoter and includes a Fur recognition sequence common to the H. pylori pfr and sodB upstream areas. Studies of Fur-regulated genes in H. pylori have indicated that apo-Fur acts as a repressor, but our results demonstrate that iron-bound Fur activates (nifS) transcription.

The human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori is well adapted for colonizing a unique niche, the stomach mucosa (3). In the mucosa it is subject to severe oxidative stress from the oxidative burst of the host immune system, which results in production of a variety of reactive oxygen intermediates (ROI) that damage macromolecules of the bacterium (21). Due to the Fenton reaction, the ROI are especially a problem in the presence of excess free intracellular iron (7). Considering the persistent nature of H. pylori, it is not surprising that the pathogen has a repertoire of enzymes involved in detoxification of the oxidative agents or in repairing the oxidized macromolecules in the cell (1, 17, 18, 22, 24).

Although combating oxidative stress is a key to H. pylori survival, we know little about regulation of expression of the specific genes involved. To aid in understanding the overall oxygen stress-modulated gene expression in H. pylori, we compared the global gene expression of H. pylori grown at 2% versus 12% oxygen by using a microarray approach. Preliminary results from these studies showed an up-expression of expected genes, such as thioredoxin reductase, thioredoxin, superoxide dismutase (SOD), and thiol peroxidase, all enzymes known to be directly involved in combating oxidative stress. In addition, among the other highly up-regulated genes was one encoding the Fe-S cluster synthesis protein NifS. We observed an approximately fivefold up-regulation of the nifS-nifU operon (hp0220 and hp0221) after a 2-h shift from 2% to 12% O2 (Abstr. 105th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol., abstr. K-063, 2005). NifS belongs to the crucial IscS family of proteins, which is involved in Fe-S cluster formation (12). The NifS proteins provide sulfur donation via an l-cysteine desulfurase activity. The cluster maturation proteins are usually considered to be essential “housekeeping” proteins, as nearly all organisms have multiple proteins that require Fe-S clusters for their function. Thus, inactivation of the H. pylori nifS-nifU operon (hp0220 and hp0221) was previously shown to be lethal to the bacterium (12, 13).

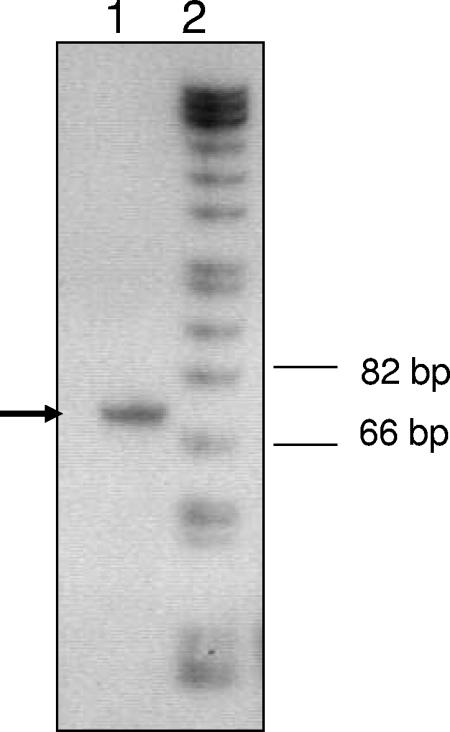

In this study we performed promoter-reporter gene fusions to determine the regulation of the nifS-nifU operon under conditions of excess oxygen or iron. We first mapped the 5′ end of the nifS-nifU transcript by using a 28-base-long oligonucleotide specific to 5′ nifS (Fig. 1). A primer extension product between 66 and 82 bases long was generated, and the 5′ end of the transcript was concluded to be approximately 38 to 54 bases upstream of the ATG start codon of nifS (hp0220). For the reporter gene fusions, a 300-bp fragment (spanning both the intergenic region of hp0219 and hp0220 and part of hp0219) comprising all of the promoter elements of nifS-nifU was amplified by PCR using the forward primer NIFPF 5′-GAGCTCGCCCATTATCATTACCGCTCT-3′ and the reverse primer NIFPR 5′-CGCCGGCGGATCCTCAAAAATTTTACATAG-3′, with the SacI site in the forward primer and the BamHI site in the reverse primer italicized. The promoter fragment was introduced upstream of a 980-bp promoterless xylE gene (encoding catechol 2,3-dioxygenase) from Pseudomonas putida. The 1,280-bp PnifS-xylE cassette was cloned into either the previously described plasmid peu39 cm (1) or the H. pylori shuttle vector pHel3 (19) to study the regulation chromosomally or extrachromosomally, respectively. The plasmids with the fusions were transformed into wild-type HP43504 or into an isogenic fur mutant to study the role of Fur in the regulation of the nifS-nifU operon.

FIG. 1.

Primer extension analysis of the nifS transcript. A primer extension system, the avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase kit (catalog no. E3030; Promega), was used to obtain the primer extension product of the nifS transcript. A 28-mer oligonucleotide (5′-TAAATTCGTTGTAACAAGGTTAATATTC-3′) complementary to the bases spanning the ATG start codon (TTG for nifS) was end labeled with [32P]ATP, and RNA from H. pylori was used as the substrate for the primer extension reaction. The reaction was carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions, and the products were subjected to PAGE (6% polyacrylamide). Lane 1, primer extension product of the nifS transcript; lane 2, DNA ladder.

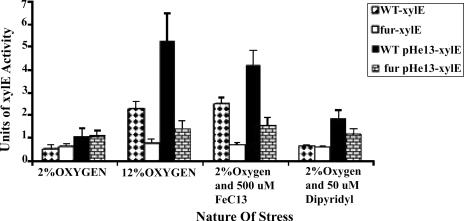

The xylE assays were performed as described elsewhere (19). Briefly, 36-h-old cells were inoculated into Mueller-Hinton broth supplemented with 10% bovine serum and grown in 2% partial-pressure oxygen (5% CO2; balance, N2). Stress conditions (excess oxygen, excess iron, or iron chelation) were applied at the logarithmic phase of growth. The XylE activities of cells grown at 2% oxygen were compared with those after stress conditions were applied (Fig. 2). The nifS-nifU operon was upregulated fourfold in 12% oxygen and threefold in excess iron, compared to the expression in 2% oxygen or 2% oxygen under iron chelation conditions, respectively. However, a similar up-expression by a high O2 or high iron concentration was not observed in a fur mutant background, indicating that Fur in H. pylori perhaps acts as either a direct or an indirect transcriptional activator of the nifS operon. To our knowledge, this is the first evidence that Fur in H. pylori is an activator, in contrast to its widely accepted role as an iron-dependent repressor (5, 10). The genome-wide response of H. pylori to iron starvation is highly significant (16). The ferric uptake regulator (Fur) in H. pylori is a key iron-sensing protein that has been shown to directly regulate synthesis of ferritin and SOD and to influence the expression of iron transport genes in H. pylori (2). Based on a genome-wide transcriptional profile, it was concluded that expression of many H. pylori genes, even outside iron metabolism, is regulated by Fur (9).

FIG. 2.

XylE activities as a measure of nifS induction under various stress conditions. Cells were grown at 2% partial pressure oxygen until logarithmic phase (an optical density at 600 nm of ∼0.4); oxygen was added to 12% partial pressure in a closed gas system, or the 2% O2 atmosphere was maintained but the medium (see the text) was supplemented with 500 μM FeCl3 or with a 75 μM concentration of the iron chelator 2,2-dipyridyl, to study the effects of oxygen stress, iron, and iron starvation on transcription of the gene. WT-xylE and fur-xylE, PnifS-xylE fusion in the hp405 region of the genome; pHel3-xylE, PnifS-xylE fusion on the shuttle vector. Simultaneous experiments were conducted in wild-type and fur mutant strain backgrounds. The means and standard deviations from five independent experiments are shown here, with three replicates for each experiment (a total of 15 samples for each mean). All wild-type results for both the added-O2 and the iron stress conditions are significantly greater than for the 2% O2 conditions (P < 0.01), and the results for the fur strain are significantly less (P < 0.01) than for the same stress condition (12% O2 or supplemented iron) for the wild-type strain. The iron chelator conditions are not statistically different from the 2% O2 conditions. One unit of xylE activity is equal to 1 μmol of oxidized catechol/min/109 cells.

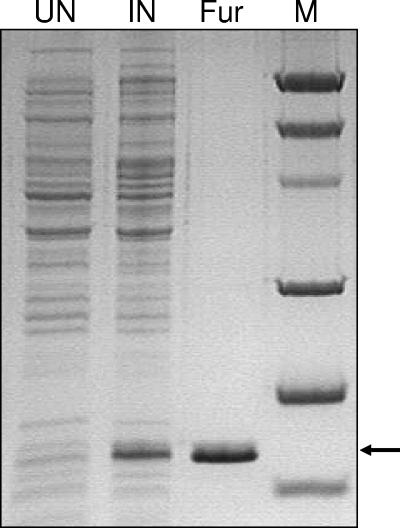

The question of whether Fur acts by directly binding to the promoter sequences of the nifS-nifU operon was addressed with gel retardation assays. H. pylori Fur was purified as a recombinant protein in Escherichia coli BL21 Rosetta. The purity of the 18-kDa Fur protein was assessed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-15% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (Fig. 3). The DNA substrate for the assay was prepared by end labeling the 300-bp promoter fragment with [γ-32P]ATP (catalog no. PB10168; Amersham) using T4 polynucleotide kinase (Promega). Fur-PnifS binding assays were carried out in standard electrophoretic mobility shift assay buffer (20). Pure Fur (200 nM) plus (iron-substituted) MnCl2 bound the 300-bp PnifS fragment (Fig. 4A). The effect of 150 μM EDTA (Fig. 4B) on the Fur-PnifS binding complex was assessed. We observed that EDTA prevented the binding of Fur to PnifS even at the highest tested concentration (1,000 nM) of Fur. The results indicate that iron-loaded Fur is the active form. We next performed a titration assay of Fur-PnifS binding by using a fixed concentration (50 pM) of radiolabeled nifS promoter and various concentrations (0 to 1,000 nM) of Fur in the presence of 100 μM MnCl2. An initially linear increase in binding was observed with the added incremental increases in Fur concentration; the binding was saturated at about 1,000 nM. The half-dissociation concentration (Kd) at which 50% of the DNA was bound was calculated to be 360 nM (Fig. 4C). For comparison, the binding affinity of apo-Fur (in the absence of iron or manganese) for the H. pylori sodB promoter is 260 nM (10). We consistently observed Fur binding to sequences that included up to 300 bp upstream of the start codon, but no Fur binding was observed when a sequence containing the 138-bp region immediately upstream was used (Fig. 4D).

FIG. 3.

Purification of H. pylori Fur. The entire gene (hp1027) from H. pylori encoding Fur was introduced downstream of the T7 promoter in the pET21A vector (Novagen) and overexpressed in E. coli BL21 Rosetta by induction with 0.5 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) (Sigma) at 30°C for 3 h. The cytoplasmic protein from crude extracts prepared from the IPTG-induced cells was obtained by ultracentrifugation (45,000 rpm for 2 h). The purification was performed by fast-protein liquid chromatography; the cytoplasmic protein was first passed through a HiTrap SP column for ion-exchange-based purification with a salt gradient of 50 mM to 1,000 mM NaCl (obtained by using buffer A [50 mM sodium phosphate-50 mM NaCl, pH 8.0] and buffer B [50 mM sodium phosphate-1,000 mM NaCl, pH 8.0]). Peak fractions containing Fur protein (from the ion-exchange procedure) were collected and further purified based on size exclusion by using a Sephacryl-200 column (buffer C [50 mM sodium phosphate-200 mM NaCl, pH 8.0]). UN, uninduced; IN, induced with 0.5 mM IPTG; Fur, purified Fur; M, molecular mass marker (masses, reading down from the top band, are 97.4, 66.2, 45.0, 31.5, 21.0, and 14.4 kDa).

FIG. 4.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay. The Fur-PnifS interaction was studied with the 300-bp radiolabeled PnifS fragment and pure Fur protein. PnifS (50 pM) was assayed with various MnCl2 concentrations and constant Fur levels (A) or with increasing concentrations of Fur (0 to 1,000 nM) in the presence of 150 μM EDTA (B). Fur-PnifS binding was determined with 100 μM MnCl2 and various concentrations of Fur; the percent DNA bound was determined by phosphorimager scanning, and then the Kd value was calculated from all of the (bound and unbound) values (C). A 150-bp interior region of the gene encoding the 16S rRNA and pure thioredoxin reductase, representing nonspecific DNA and protein, respectively, were used as controls; these exhibited no shift (data not shown). The region of Fur recognition in PnifS (in the presence of MnCl2) was narrowed by use of a 138-bp non-Fur-binding fragment upstream of the start codon rather than the 300-bp fragment used in other experiments. The inability of this fragment to bind Fur is shown (D).

The entire 300-bp fragment was analyzed for potential Fur recognition sequences with a DNase protection assay. We used the radiolabeled oligonucleotides NIFSPF and NIFSPR to amplify the promoter region, and it was incubated with increasing concentrations of Fur (0 to 10 μM) in the presence or absence of 100 μM MnCl2. DNase enzyme (1 μl at 0.05 U/μl) (catalog no. M6101; Promega, Madison, Wis.) was added to the reaction, and the reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for 45 s. The reaction was stopped by adding 3 μl of stop solution, and the sample was purified with QIAGEN spin columns; the DNA was eluted with 10 μl of H2O, and 6 μl of denaturing loading dye was then added to the eluant. The entire mixture (approximately 16 μl) was subjected to PAGE (6% polyacrylamide gel containing 8 M urea) for several hours at 1,200 V. The two approximate areas protected from DNase activity were −155 to −190 bp and −210 to −240 bp in the nifS promoter (data not shown); within both of these areas are conserved Fur boxes that correspond to the identified Fur binding areas of the H. pylori pfr and sodB promoters (2, 7, 10). No DNase protection was detected in the absence of MnCl2, even at the highest concentration of Fur (data not shown). The xylE assays combined with the EDTA experiment and the MnCl2-dependent binding assays indicate that, unlike the previously reported H. pylori Fur-interacting promoters (2, 5, 10), Fur acts as a transcriptional activator of nifS in an iron-dependent fashion.

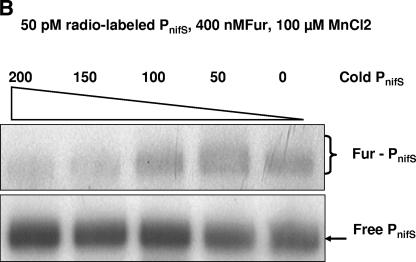

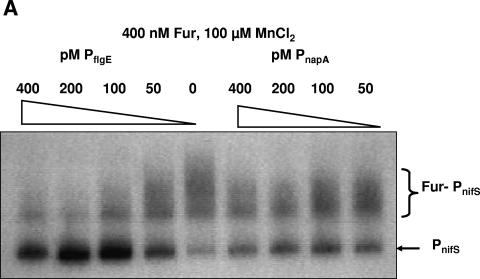

To compare the affinity of PnifS-Fur to other promoters, we carried out a competition assay using the flgE and napA promoters, which were previously shown to be repressed by apo-Fur (9, 23). The competition assay was performed in the presence of MnCl2 (Fig. 5A) using 400 nM Fur, 50 pM labeled PnifS, and a range (0 to 400 pM) of 200-bp flgE or napA promoter DNA. We observed that at about a 4× excess concentration (compared to PnifS), PflgE reduced the binding of Fur to PnifS by more than 50%. There was little or no inhibition of PnifS-Fur interaction by PnapA. Cooksley et al. (4) showed that napA in H. pylori is repressed by Fur but that expression is induced when the cells are grown in medium supplemented with FeCl3, and in a fur mutant strain napA expression did not depend on iron levels (4). In our study, the competition experiment was performed in the presence of MnCl2 (a preferable substitute for iron, as previously described; see reference 11), which is needed for Fur-PnifS binding. For napA regulation, it seems that apo-Fur is the active form that recognizes the promoter; hence, it is not surprising that the napA promoter could not successfully inhibit the Fur-PnifS complex. When a similar experiment was performed with cold PnifS as the competitor DNA, the binding of Fur to radiolabeled PnifS was decreased to approximately 25% (compared to binding in the absence of competitor) in the presence of a 200 pM concentration of competitor promoter (Fig. 5B); this suggests a specific binding of Fur to PnifS.

FIG.5.

(A) Competitive effects of PflgE and PnapA on Fur-PnifS (PnifS at 50 pM) binding in the presence of 100 μM MnCl2 determined by using increasing concentrations (0 to 400 pM) of competitor promoter DNA. (B) Effects of cold PnifS (0 to 200 pM) on Fur binding to radiolabeled nifS promoter DNA.

H. pylori Fur has been well studied as a transcriptional repressor, and the iron-dependent transcriptional induction activity has been most well studied for the regulation of sodB and pfr. apo-Fur recognizes the Fur box consensus sequence upstream of the promoter region of these genes and inhibits transcription by blocking the movement of RNA polymerase (10). Under conditions of excess free iron in the cell, the transcription of Fur-regulated genes occurs by the derepression by iron-bound Fur (2, 5, 10, 23). Thus, Fur in H. pylori acts as a classical transcriptional repressor, in contrast to its role as a positive regulator as exemplified in the case of E. coli sodB (8); in the latter case, Fur was required for the transcription of the gene encoding Fe-SOD under both anaerobic and aerobic conditions of growth (in a RhyB-dependent mechanism) (14, 15). Although sequences more than 150 bp upstream have been proposed to be potential Fur binding areas, documented H. pylori Fur binding has been observed no more than 70 to 80 bp upstream of the transcription start site (4, 6, 7). The upstream binding we observed may be related to the different type of regulation (positive regulation by the iron-bound form) observed herein. In a recent study regarding the transcriptional profiling of H. pylori iron-regulated gene expression (9), the authors observed a large set of genes whose regulation was modulated by the intracellular levels of iron and another subset of genes (mod, murE, and rnhB) that were down-regulated in a fur mutant. The latter result was interpreted as an aberration from the accepted model of Fur-dependent regulation and was speculated to be an indirect form of Fur-dependent regulation. In addition, nifS was observed to be among another set of genes that included carbonic anhydrase and a thioredoxin that were further aberrantly expressed (9); iron levels did not significantly affect that expression in the wild type. However, that transcriptome study used a higher O2 level in the supplemental iron experiment than did our study, as well as a different parent strain.

In our study, we report that the nifS-nifU operon of H. pylori is up-regulated under high oxygen or high iron conditions; the observed up-regulation was not observed in an isogenic fur mutant. The oxygen effect is most likely related to the recently reported damaging effect of O2 and related ROI on the release of free iron from Fe-containing proteins in H. pylori (25). The net result is a significant increase of intracellular free iron, which we expect would be recognized by Fur. The connection between increased oxygen stress and NifS expression is presumably related to the increased need for Fe-S cluster synthesis at a time when Fe-S proteins are oxidatively damaged. Further analysis of the nifS promoter and other H. pylori iron-regulated promoters is needed for understanding of the full role of Fur.

Acknowledgments

We thank Adriana Olczak for providing the fur mutant.

This work was supported by NIH grant 1-RO1-DK60061 to R.J.M.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alamuri, P., and R. J. Maier. 2004. Methionine sulphoxide reductase is an important antioxidant enzyme in the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Mol. Microbiol. 53:1397-1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bereswill, S., S. Greiner, A. H. van Vliet, B. Waidner, F. Fassbinder, E. Schiltz, J. G. Kusters, and M. Kist. 2000. Regulation of ferritin-mediated cytoplasmic iron storage by the ferric uptake regulator homolog (Fur) of Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 182:5948-5953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blaser, M. J. 1997. The versatility of Helicobacter pylori in the adaptation to the human stomach. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 48:307-314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooksley, C., P. J. Jenks, A. Green, A. Cockayne, R. P. Logan, and K. R. Hardie. 2003. NapA protects Helicobacter pylori from oxidative stress damage, and its production is influenced by the ferric uptake regulator. J. Med. Microbiol. 52:461-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delany, I., A. B. Pacheco, G. Spohn, R. Rappuoli, and V. Scarlato. 2001. Iron-dependent transcription of the frpB gene of Helicobacter pylori is controlled by the Fur repressor protein. J. Bacteriol. 183:4932-4937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delany, I., G. Spohn, A. B. Pacheco, R. Ieva, C. Alaimo, R. Rappuoli, and V. Scarlato. 2002. Autoregulation of Helicobacter pylori Fur revealed by functional analysis of the iron-binding site. Mol. Microbiol. 46:1107-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delany, I., G. Spohn, R. Rappuoli, and V. Scarlato. 2001. The Fur repressor controls transcription of iron-activated and -repressed genes in Helicobacter pylori. Mol. Microbiol. 42:1297-1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dubrac, S., and D. Touati. 2000. Fur-positive regulation of iron superoxide dismutase in Escherichia coli: functional analysis of the sodB promoter. J. Bacteriol. 182:3802-3808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ernst, F. D., S. Bereswill, B. Waidner, J. Stoof, U. Mader, J. G. Kusters, E. J. Kuipers, M. Kist, A. H. van Vliet, and G. Homuth. 2005. Transcriptional profiling of Helicobacter pylori Fur- and iron-regulated gene expression. Microbiology 151:533-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ernst, F. D., G. Homuth, J. Stoof, U. Mader, B. Waidner, E. J. Kuipers, M. Kist, J. G. Kusters, S. Bereswill, and A. H. van Vliet. 2005. Iron-responsive regulation of the Helicobacter pylori iron-cofactored superoxide dismutase SodB is mediated by Fur. J. Bacteriol. 187:3687-3692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Escolar, L., J. Perez-Martin, and V. de Lorenzo. 1999. Opening the iron box: transcriptional metalloregulation by the Fur protein. J. Bacteriol. 181:6223-6229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson, D. C., D. R. Dean, A. D. Smith, and M. K. Johnson. 2005. Structure, function, and formation of biological iron-sulfur clusters. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 74:247-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson, D. C., P. C. Dos Santos, and D. R. Dean. 2005. NifU and NifS are required for the maturation of nitrogenase and cannot replace the function of isc-gene products in Azotobacter vinelandii. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 33:90-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masse, E., and S. Gottesman. 2002. A small RNA regulates the expression of genes involved in iron metabolism in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:4620-4625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masse, E., C. K. Vanderpool, and S. Gottesman. 2005. Effect of RyhB small RNA on global iron use in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 187:6962-6971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merrell, D. S., L. J. Thompson, C. C. Kim, H. Mitchell, L. S. Tompkins, A. Lee, and S. Falkow. 2003. Growth phase-dependent response of Helicobacter pylori to iron starvation. Infect. Immun. 71:6510-6525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olczak, A. A., J. W. Olson, and R. J. Maier. 2002. Oxidative-stress resistance mutants of Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 184:3186-3193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olczak, A. A., R. W. Seyler, Jr., J. W. Olson, and R. J. Maier. 2003. Association of Helicobacter pylori antioxidant activities with host colonization proficiency. Infect. Immun. 71:580-583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olson, J. W., and R. J. Maier. 2002. Molecular hydrogen as an energy source for Helicobacter pylori. Science 298:1788-1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pereira, L., and T. R. Hoover. 2005. Stable accumulation of σ54 in Helicobacter pylori requires the novel protein HP0958. J. Bacteriol. 187:4463-4469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sachs, G., D. L. Weeks, K. Melchers, and D. R. Scott. 2003. The gastric biology of Helicobacter pylori. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 65:349-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seyler, R. W., Jr., J. W. Olson, and R. J. Maier. 2001. Superoxide dismutase-deficient mutants of Helicobacter pylori are hypersensitive to oxidative stress and defective in host colonization. Infect. Immun. 69:4034-4040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Vliet, A. H., J. Stoof, R. Vlasblom, S. A. Wainwright, N. J. Hughes, D. J. Kelly, S. Bereswill, J. J. Bijlsma, T. Hoogenboezem, C. M. Vandenbroucke-Grauls, M. Kist, E. J. Kuipers, and J. G. Kusters. 2002. The role of the ferric uptake regulator (Fur) in regulation of Helicobacter pylori iron uptake. Helicobacter 7:237-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang, G., P. Alamuri, M. Z. Humayun, D. E. Taylor, and R. J. Maier. 2005. The Helicobacter pylori MutS protein confers protection from oxidative DNA damage. Mol. Microbiol. 58:166-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang, G., R. C. Conover., A. A. Olczak, P., and M. K. J. Alamuri, and R. J. Maier. 2005. Oxidative stress defense mechanisms to counter iron-promoted DNA damage in Helicobacter pylori. Free Radic. Res. 30:1183-1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]