Abstract

Many individuals chronically infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) experience a recrudescence of plasma virus during continuous combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) due either to the emergence of drug-resistant viruses or to poor compliance. In most cases, virologic failure on ART is associated with a coincident decline in CD4+ T lymphocyte levels. However, a proportion of discordant individuals retain a stable or even increasing CD4+ T lymphocyte count despite virological failure. In order to address the nature of these different outcomes, we evaluated virologic and immunologic variables in a prospective, single-blinded, nonrandomized cohort of 53 subjects with chronic HIV-1 infection who had been treated with continuous ART and monitored intensively over a period of 19 months. In all individuals with detectable viremia on ART, multiple drug resistance mutations with similar impacts on viral growth kinetics were detected in the pol gene of circulating plasma virus. Further, C2V3 env gene analysis demonstrated sequences indicative of CCR5 coreceptor usage in the majority of those with detectable plasma viremia. In contrast to this homogeneous virologic pattern, comprehensive screening with a range of antigens derived from HIV-1 revealed substantial immunologic differences. Discordant subjects with stable CD4+ T lymphocyte counts in the presence of recrudescent virus demonstrated potent virus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocyte responses. In contrast, subjects with virologic failure associated with declining CD4+ T lymphocyte counts had substantially weaker HIV-specific CD4+ T lymphocyte responses and exhibited a trend towards weaker HIV-specific CD8+ T lymphocyte responses. Importantly the CD4+ response was sustained over periods as long as 11 months, confirming the stability of the phenomenon. These correlative data lead to the testable hypothesis that the consequences of viral recrudescence during continuous ART are modulated by the HIV-specific cellular immune response.

Highly active combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) has revolutionized the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection and produced substantial reductions in AIDS-related morbidity and mortality (9, 14, 24). The optimal result of ART administration is a dramatic and sustained decrease in HIV-1 replication with an associated rise in CD4+ T lymphocyte counts and improved immune function (1, 16, 19). In the majority of antiretroviral drug-naïve patients, and in various proportions of antiretroviral drug-experienced patients, initiation of combination therapy results in a reduction in plasma virus load (pVL) to below the detection limit of currently available assays (generally <50 copies of HIV-1 RNA/ml) (32). However, it is clear that viral eradication cannot be achieved with current strategies (5, 10, 33). The aim of therapeutic intervention at present is therefore the long-term suppression of virus replication to ensure maintenance of total CD4+ T lymphocyte numbers and hence continuous treatment benefit (4, 22).

The response to ART has generally been defined in terms of plasma virus quantification and CD4 recovery. Virologic failure may occur for a number of reasons, including poor adherence to medications, inadequate drug levels due to pharmacokinetic interactions or suboptimal dosing, or the emergence of drug-resistant virus due to previous antiretroviral exposure. As a result, pVL increases and may return to pre-ART levels over a period of weeks or months. This is most often accompanied by a fall in the CD4+ T lymphocyte count and a deterioration in general immune function with consequent clinical implications. However, in a small minority of patients, estimated at 5% (25), virologic failure is associated with a discordant increase in CD4+ T lymphocyte counts (6, 15, 18, 25, 27). In these patients, pVL may reach undetectable levels initially, but then increases after several weeks or months to stabilize at a moderate level while the total CD4+ T lymphocyte count is maintained and may even continue to rise in the face of virologic relapse. The mechanisms that underlie these different outcomes in the presence of virologic failure are unclear, but could reflect either viral or host factors. It is known that in discordant patients with stable CD4 counts in the presence of detectable pVL, cessation of antiretroviral therapy leads to a further increase in pVL and a fall in total CD4+ T lymphocyte counts (6). Thus, this discordant response is dependent on continued ART despite virologic breakthrough.

To identify the biological correlates of these divergent treatment outcomes, we characterized HIV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocyte responses and virologic variables in a total of 53 patients with established HIV-1 infection receiving continuous ART. This cohort comprised 24 patients in whom pVL was maintained at <50 copies of HIV-1 RNA/ml and total CD4+ T lymphocyte counts remained elevated, 8 patients with virologic failure and declining CD4+ T lymphocyte counts, and 21 discordant patients with virologic failure associated with preservation of CD4+ T lymphocyte counts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population.

All patients were drawn from the Jefferiss Wing Clinic at St Mary's Hospital, London, United Kingdom. Patients were grouped according to their response to the initiation of continuous ART during chronic HIV-1 infection. The Success group (S) comprised individuals with pVL suppression to <50 copies/ml for a minimum of 12 months on ART associated with a sustained rise in total CD4+ T lymphocyte counts (n = 24). The Failure group (F) comprised individuals with an initial reduction in pVL to <1,000 copies/ml after initiation of ART, followed by a sustained increase in pVL (>1,000 copies/ml) associated with declining CD4+ T lymphocyte numbers (n = 8). The Discordant group (D) comprised individuals with an initial reduction in pVL to <1,000 copies/ml (15 of 21 achieved a pVL of <50 copies/ml) after initiation of ART, with a subsequent increase in pVL to >1,000 copies/ml on at least two occasions 3 months apart associated with a stable or increasing total CD4+ T lymphocyte count (n = 21) (Fig. 1). The time point of analysis in each patient was representative of the stable clinical situation. Demographic data and patient details are summarized in Table 1. Patients within the three different groups, S, D, and F, were matched for age and for duration of HIV infection.

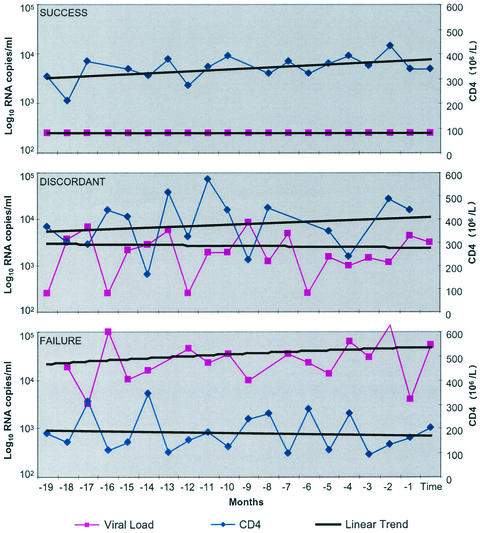

FIG. 1.

Characterization of the three patient groups (S, D, and F) by longitudinal analysis of pVL and total CD4+ T lymphocyte count. The three clinical groups were derived following close clinical and laboratory monitoring of the 53 patients over a period of 19 months. The time of the sampling for this study is defined as month 0. The median pVL (log copies/ml) and median CD4 (106 cells/liter) counts are shown over the 19 months prior to the date of sampling. The regression slopes for median CD4 counts show that group S (n = 24) had a positive CD4 slope and undetectable pVL over this period; group F (n = 8) had detectable pVL and a negative CD4 slope. Group D (n = 21) had detectable pVL and a positive CD4 slope over this period.

TABLE 1.

Demographic data and patient details

| Characteristic | Patient groupa

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| S | D | F | |

| n | 24 | 21 | 8 |

| No. of males/females | 23/1 | 20/1 | 8/0 |

| Age (mean [yr]) | 45 | 41 | 41 |

| Duration of infection (mean mo.) | 95 | 99 | 84 |

| Pre-ART pVL (median log copies/ml) | 5 | 4.75 | 5.52 |

| Pre-ART CD4 count (median cells/mm3) | 170 | 165 | 125 |

| No. of regimens | 2 | 2 | 2.5 |

| Time on present ART (mean mo.) | 18 | 28 | 21 |

| Total duration of ART (mean mo.) | 45 | 60 | 41 |

| Duration of pVL of <50 copies/ml (mean mo.) | 24 | n.a. | n.a. |

| Duration of stable discordant status (mean mo.) | n.a.b | 20 | n.a. |

| pVL at analysis (median log copies/ml) | <1.7 | 3.47 | 4.61 |

| CD4 count at analysis (median cells/mm3) | 404 | 400 | 125 |

| Drugs takenc | |||

| NRTI | 0 | 4 | 2 |

| NNRTI | 19 | 6 | 3 |

| PI | 4 | 6 | 2 |

| NNRTI + PI | 1 | 5 | 1 |

S (success), chronic HIV patients on ART with suppression of pVL to <50 copies/ml for a minimum of 12 months and continuous rise to CD4 counts; D (discordant), chronic HIV patients on ART with partial suppression of pVL and evidence of stable viral load (>1,000 copies of RNA/ml) on at least two occasions 3 months apart with CD4 counts stable or increasing; F (failure), chronic HIV patients on ART who fail therapy after reaching undetectable levels or having never reached undetectable levels, with escalating viral loads and decline in CD4 counts.

n.a., not applicable.

NRTI, nucleoside analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitor; NNRTI, nonnucleoside analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor.

Drug resistance genotyping of pol.

Samples were sequenced in pol by using either Trugene (Visible Genetics, Evry, France) or the ViroSeq vII HIV genotyping system (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, United Kingdom) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, RNA was extracted from pelleted HIV-1 from patient plasma by using either spin columns (Qiagen, Teddington, United Kingdom) (Trugene method) or isopropanol-ethanol precipitation (Viroseq method). The RNA was converted to cDNA by using kit reagents and then amplified by PCR. The amplicon constituted approximately 1.4 kb of pol, including all of protease (PR) and the first 250 to 300 codons of reverse transcriptase (RT). The PCR product was sequenced in both the 5′ and 3′ directions by using overlapping fragments and dye terminator chemistry. All amplification and sequencing reactions were carried out on a model 9700 thermocycler (Perkin Elmer, Warrington, United Kingdom). The sequences were read either on a Visible Genetics long tower open gene system with the Trugene software or on an ABI 310 genetic analyzer with the Viroseq HIV analysis software (version 2). Sequences were converted to either text files (Visible Genetics) or Fasta files (Applied Biosystems) and subtyped with the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Blast algorithm software (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov /retroviruses/subtype/htlm).

Generation of primary virus isolates.

Attempts were made to obtain primary virus isolates from plasma samples by short-term culture with phytohemagglutinin (PHA)-stimulated seronegative donor peripheral blood leukocytes (PBL) which had been CD8 depleted (Dynal United Kingdom Ltd., Bromborough, Wirral, United Kingdom). Virions were separated from plasma by ultracentrifugation (105,000 × g for 6 min) prior to culture. Cultures were maintained for 28 days in recombinant interleukin-2-containing medium, and supernatants were collected on days 7, 14, 21, and 28 for p24 antigen determination as a means of determining the presence of infectious virus and tissue culture infectious dose (TCID).

Generation of recombinant viruses.

Viruses with recombinant PR and RT were generated essentially as described previously (3, 21). Briefly, RNA from patient plasma was isolated by standard methodology (Qiagen) and subjected to RT-PCR with a GeneAmp RNA PCR kit (Applied Biosystems) and DNA PCR primers as described previously (3, 21); 1 ng of purified PCR product (Qiagen) was electroporated into 5 × 106 SupT1 cells along with 1 ng each of pHXBΔRT and pHXBΔPR by using a Bio-Rad gene pulser with a 4-mm cuvette at 250 volts and 950 μF with an extension time of 40 to 60 ms. Supernatants were taken at the peak of virus replication, as determined by syncytium formation, and stored in liquid nitrogen. Working virus stocks were produced following short-term single passage on SupT1 cells. Median 50% TCID (TCID50) was determined on MT2 cells cultured in RPMI 1640 with 15% fetal calf serum and PBL stimulated with PHA and recombinant interleukin-2 by syncytium formation or a p24 antigen readout. Viral replication kinetics were determined on mitogen-activated PBL over a 16-day period following infection with a standardized input amount of each virus stock. The TCID50 of the virus stock was determined in parallel to confirm the level of infectious virus used. The plasmids pHXBΔRT and pHXBΔPR were a generous gift from Charles Boucher, University Hospital, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

C2V3 Env sequencing.

Viral RNA was extracted from plasma using the QIAamp viral RNA kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.). RNA extract (3 to 7 μl) was used to synthesize cDNA with the primer GP41R (35) and the GeneAmp RNA PCR kit, following the manufacturer's instructions (Applied Biosystems, Branchburg, N.J.). Five to 10 μl of the cDNA reaction mixture was used to amplify a 1.2-kb fragment of env (gp120) by nested PCR with outer (ED3/ED14) and inner (ED5/ED12) primers, as described previously (7). The PCR product was cleaned by standard methodology, and automated sequencing was performed with the dRhodamine terminator cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, United Kingdom) and the forward and reverse primers ES7 (7) and ED33R (5′-TTACAGTAGAAAAATTCCCCTC), respectively. Both product sequences were aligned by using SeqEd version 1.0.3 (Applied Biosystems), and the consensus was translated. Assignment of the speculative biological phenotype (non-syncytium-inducing [NSI] versus syncytium-inducing [SI]) was made according to the charge of amino acid residues at positions 11 and 25 (numbering the first residue in the V3 as 1), according to Fouchier et al. (11, 12).

Determination of pVL.

Virus load was quantified by the Chiron 3 bDNA assay, with a lower limit of detection of 50 HIV-1 RNA copies/ml and an upper limit of 500,000 copies/ml.

Assessment of functional HIV-specific CD4+ T lymphocyte frequencies.

Patient PBL were separated from heparinized blood by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation. Freshly isolated PBL were depleted of CD8+ T cells prior to analysis with anti-CD8 monoclonal antibody-conjugated magnetic beads (Dynal United Kingdom Ltd.). Recombinant proteins (gp120, p24, and p66 at 10 μg/ml; NIBSC, Potters Bar, United Kingdom) and overlapping pooled peptides, each 20 amino acids long with a 10-residue overlap, spanning full-length proteins (Tat and Nef at 5 μg/ml; NIBSC) derived from HIV-1 were used to determine HIV-specific CD4+ T cell frequencies directly ex vivo by gamma interferon (IFN-γ) enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) analysis (23). The HIV-unrelated recall antigens streptokinase (SK) and streptodornase (SD) (200 U/ml; Lederle, Hamburg, Germany) and nonspecific PHA stimulation (5 μg/ml) were used as positive controls in all assays. Nonrecombinant baculovirus and medium alone were used as negative controls. Results are expressed as specific spot-forming cells (SFC) per 106 CD8-depleted PBL; background values were subtracted from the specific response before normalization to the number of SFC per 106 CD8-depleted PBL. A positive response to a given antigen was defined as a number of SFC/106 CD8-depleted PBL greater than 3 standard deviations above background and was generally more than 50 SFC/106 CD8-depleted PBL. Spot quantification was automated and standardized with an ELISPOT plate reader (Autoimmun Diagnostika, Strassberg, Germany; software version 2.1). All assays were performed in duplicate.

Assessment of functional HIV-specific CD8+ T lymphocyte frequencies.

Comprehensive analysis of HIV-specific CD8+ T cell responses was performed directly ex vivo by IFN-γ ELISPOT analysis, as previously described (17, 23). Briefly, cryopreserved PBL were screened with pooled overlapping peptides, each 20 amino acid residues long with a 10-residue overlap, spanning HIV RT, Env, p24 Gag, p17 Gag, Nef, Tat, and Rev (NIBSC) at a final concentration of 5 μg/ml for each individual peptide within a pool. Each peptide pool comprised 10 individual peptides. PHA was always included as a positive control, and the use of medium alone allowed determination of nonspecific background. Spot quantification was automated and standardized by using an ELISPOT plate reader (Autoimmun Diagnostika; software version 2.1). All assays were performed in duplicate.

Statistical analysis.

All data except pol codon changes were analyzed with release 13 of Minitab statistical software (Minitab Statistical Software User's Guide 1, Release 13, Minitab Inc., State College, Pa.). All statistical analyses shown used the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. The impact of codon changes within pol was analyzed by using the chi-square test and Fisher's exact test for discrete variables.

RESULTS

Patient groups.

The characteristics of the three patient groups over 19 months of observation prior to sampling are shown in Fig. 1. Group S (n = 24) had suppressed pVL (log copies/ml) to undetectable levels, with a positive CD4 slope over this period. Group F (n = 8) had detectable pVL over the observation period, with a negative CD4 slope. Group D (n = 21) had detectable pVL, but a positive CD4 slope, maintained over the period of 19 months prior to sampling for this study. Having defined these three distinct and stable patient populations, we were able to sample at a single point in time in order to compare the virologic and immunologic characteristics associated with the discordant phenotype.

Virology. (i) pVL before and during ART.

Pretreatment pVL was compared between the three groups, Success (S), Discordant (D), and Failure (F). The distribution of pre-ART pVL in groups S, D, and F showed that patients in groups S and D tended to have lower pre-ART pVL than those in group F (Table 1). Pretreatment pVL was above 500,000 copies/ml in 42% of patients in group F, compared to 14 and 6% of patients in groups S and D, respectively. During continuous ART, and according to the definition of the groups, pVL in group S was suppressed to <50 copies/ml for a mean of 24 months (Table 1; Fig. 1 and 2); pVL in group D was at a median of log 3.47 copies/ml and in group F at a median of log 4.61 copies/ml (Table 1; Fig. 1). This difference in pVL did not reach statistical significance (Tables 2 and 3).

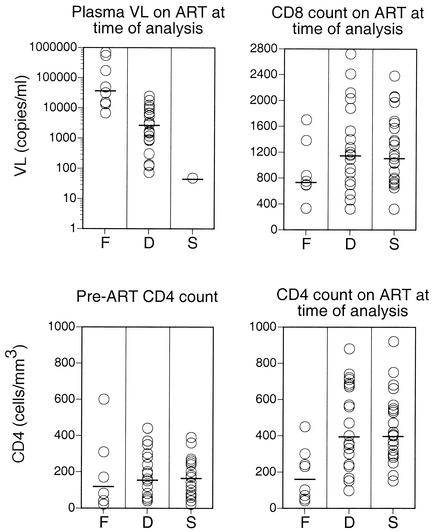

FIG. 2.

pVL and total CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocyte counts for the three groups, F, D, and S, at the time of analysis. pVL on continuous ART at the time of analysis is shown in the upper left panel. Total CD4+ T lymphocyte counts before ART are shown in the lower left panel, and total CD4+ T lymphocyte counts on continuous ART at the time of analysis are shown in the lower right panel. Total CD8 counts on continuous ART at the time of analysis are shown in the upper right panel. Each circle represents a single patient. Bars indicate median values.

TABLE 2.

Distribution of pretreatment pVLa

| Patient group | No. of patients with pretreatment pVL (copies/ml) of:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| >500,000 | 100,000-500,000 | 50,000-100,000 | <50,000 | |

| F | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| S | 3 | 8 | 4 | 6 |

| D | 1 | 7 | 3 | 7 |

With pretreatment comparison of pVL of groups F and D by the Mann-Whitney U test (CI, 95%; P = 0.055).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of pVL and CD4 counts of patient groups by Mann-Whitney U test (CI, 95%)

| Criterion |

P value for comparison of groups:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| F and D | F and S | D and S | |

| pVL at time of analysis | 0.095 | n.a.a | n.a. |

| Pre-ART CD4 count | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.78 |

| CD4 count at time of analysis | 0.0017 | 0.001 | 0.90 |

n.a., not applicable.

(ii) pol drug resistance genotype.

No differences were observed in the number of antiretroviral drugs received by the patients or in the number of resistant mutations detected in pol between groups D and F (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

RT resistance mutations

| Patient group, virus isolate, and comparison standard | Mutation(s) of the indicated amino acid and position

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L10 | K20 | D30 | G48 | I54 | V82 | I84 | L90 | M41 | D67 | T69 | K70 | L74 | V75 | K103 | Y181 | M184 | G190 | T215 | K219 | |

| Discordant | ||||||||||||||||||||

| V3 | R/I | N | F | L | N | R | I | F | ||||||||||||

| V7 | I | V | Y/F | |||||||||||||||||

| V8 | L | |||||||||||||||||||

| V15 | I | V | A | M | N | V | Y/C | |||||||||||||

| V17 | V | Y | ||||||||||||||||||

| V18 | I/F | V | M | L | V | C | V | A | Y | |||||||||||

| V19 | I | N | A | N | R | V | ||||||||||||||

| V29 | R/I | R | V | |||||||||||||||||

| V33 | V | A | ||||||||||||||||||

| V38 | M | I | V | |||||||||||||||||

| V40 | R | V | ||||||||||||||||||

| V43 | N | L | V | |||||||||||||||||

| V46 | I | D/A | E | V | C | A | ||||||||||||||

| V52 | I | R | V | V | S | L | N | V | V | Y | Q | |||||||||

| V53 | L | N | A | Y | ||||||||||||||||

| Failure | ||||||||||||||||||||

| V9 | T | C | A | N | ||||||||||||||||

| V13 | I/F | R | V | A | V | M | L | N | I | N | C | I | A | Y | E | |||||

| V20 | I | N | R | V | E | F | Q | |||||||||||||

| V44 | L | V | Y | |||||||||||||||||

| V45 | K/R | L | C | V | Y/F | |||||||||||||||

| V49 | V | V | V | A | V | K/T | V | |||||||||||||

| V50 | M | V | Y | |||||||||||||||||

| P valuea | 0.38 | 0.52 | 0.29 | 0.54 | 0.38 | 0.65 | 0.54 | 0.38 | 0.63 | 0.65 | 0.68 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.23 | 0.38 | 0.27 | 0.35 | 0.39 | 0.27 | 0.08 |

The impact of codon changes within pol was analyzed by using the chi-square test and Fisher's exact test for discrete variables.

(iii) Primary virus isolation and characterization from plasma and PBMCs.

Primary virus isolates were obtained from plasma samples in five of five group F patients, and these were subsequently characterized for coreceptor usage by cocultivation with U87 cells expressing CCR3, CCR5, or CXCR4. Results for V18, V21, V44, and V45 showed a coreceptor phenotype consistent with that inferred from C2-V3 sequence. No phenotype was obtained from V13, and no isolate was obtained from V50. Despite multiple attempts to isolate primary virus from plasma and PBMC samples from 10 group D patients, no successful isolation was made, and thus no coreceptor phenotype data are available.

(iv) Recombinant virus growth kinetics.

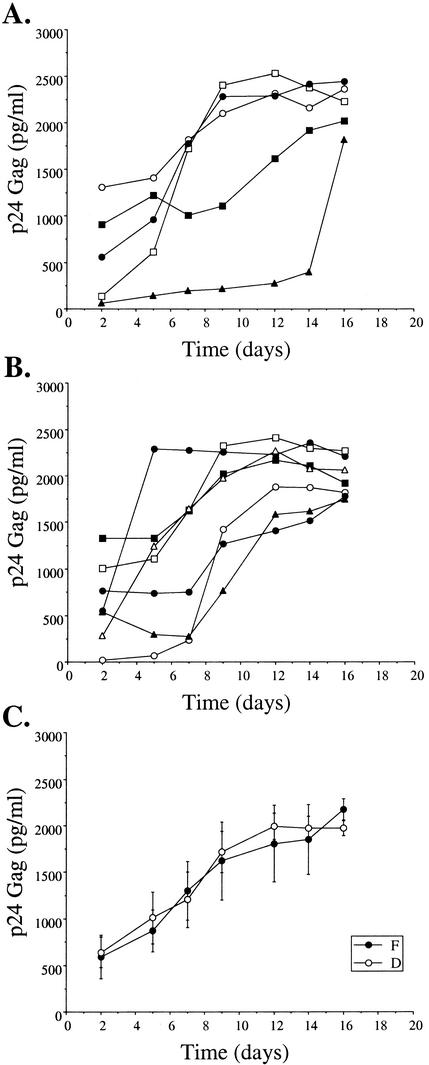

To assess the impact of natural sequence variation and those induced by the in vivo pressure of antiretroviral therapy on the replicative capacity of HIV-1, recombinant viruses were generated expressing the patient plasma-derived RT and PR genes in a standard HXB2 background. This assay has the benefit of maintaining the quasispecies diversity of the patient sequences in the generated recombinant virus stock. No clear differences were observed in the growth kinetics of 12 recombinant viruses containing the RT and PR genes from five group F patients and seven group D patients (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Recombinant virus growth kinetics. Recombinant viruses containing PR and RT genes from patient isolates were generated as described above. (A and B) Growth kinetics, determined by quantification of p24 Gag in culture supernatants, are shown for five such recombinants produced from group F patient virus isolates (A) and seven group D patient virus isolates (B); each symbol represents results for an individual recombinant. (C) The mean production at each time point from each group of viruses described for panels A and B is shown, together with bars for the standard error of the mean.

(v) C2V3 Env sequence—inference for coreceptor usage.

C2V3 sequence fragments were generated from 16 patient plasma samples, of which 6 were from group F and 10 from group D (Table 5). A speculative biological phenotype, NSI or SI, was assigned, according to Fouchier et al. (12), with its implication for coreceptor usage noted (CCR5 monotropism, R5, versus CXCR4 monotropism, X4, or CCR5 CXCR4 dual tropism, R5X4, respectively). Two out of the five group F patients and 1 of 10 patients of group D had a basic residue at either position, suggesting viruses having an SI (X4 or R5X4) phenotype in these individuals and sole CCR5 usage in the remainder. However, it has been reported (11) that in rare cases, some NSI isolates (5 of 191) had a positively charged amino acid at residue 25 but a negative or uncharged amino acid at position 11 (this could affect the SI phenotype assigned to the sequences derived from V21 and V46). In addition, in some cases (3 of 58), isolates with an SI phenotype had uncharged residues at both positions (11).

TABLE 5.

Deduced amino acid sequence of the V3 region of Env in group D and F patients

| Virus and patient group | V3 amino acid sequencea | Phenotypeb

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Charge | NSI or SI | ||

| HIV-1 subtype B JR-FL | IVQLKESVEINCTRPNNNTRKSIHIGPGRAFYTTGEIIGDIRQAHCNISRAKWNDTLKQIVIKLRE | +4 | NSI |

| Group D | |||

| V17 | ....N...A.......................A.E...........I.N.TE..N..T...E.... | +5 | NSI |

| V19 | ....ADP.K......G.......R....S......G.............GKE..N..R..AE..Q. | +5 | NSI |

| V20 | ....T...N.T..............A..K...A.-D......R.......TN.T...QK..T..G. | +6 | NSI |

| V29 | ....N...V...........G.........F...D......K.Y..V.KTA..N......V.... | +5 | NSI |

| V38 | ....N...S.S.A...................................V.GG...EA.R..AV.... | +5 | NSI |

| V40 | .....HR.N.T.I..........P........A..D...............E.KS..NET.K..GK | +4 | NSI |

| V43 | ......................G.S........A................K...DK.........K. | +4 | NSI |

| V46 | .....K...............A.R......V.A.ER.............GKN..K..A...T..K. | +6 | SI |

| V52 | ........V............G...........................G.A..K..Q...V.... | +5 | NSI |

| V53 | ....N.T.Q..............R....ST..A..D...........L..TN.TN..N..AR.... | +4 | NSI |

| Group F | |||

| V13 | ....N.TIK.D.V..........P...........D...........L.KEA.N......T...A | +4 | NSI |

| V18 | ..H.N..............S.R.S.......TARERV..........L..TQ..N......E.... | +6 | SI |

| V21 | ........A............G.......V..A.DK........Y.T.NKTQ..T..S..K.... | +5 | SI |

| V44 | ......T.V..............N....S.I.A..............V.EKD.TNA.R..A..... | +3 | NSI |

| V45 | ....N...V............G..........A..............L..TH.EK...RVA..... | +5 | NSI |

| V50 | ........Q............G......S......D............TETQ.KK......E..K. | +4 | NSI |

Dots indicate amino acid identity, and dashes indicate gaps in alignment.

Speculative biological phenotype was assigned by the relative charge of specific V3 amino acid residues. Overall charge of the V3 region was determined by assigning amino acid residues with a positively charged (K, R, H) or negatively charged (D, E) R group a value of +1 or −1, respectively, while the NSI (monotropic CCR5-using) or SI (monotropic CXCR4-using or dual CCR5- and CXCR4-using) phenotype was assigned based on whether an amino acid residue at position 11 or 25 (numbering the first residue in the V3 region as 1) has a positively charged R group.

Immunology. (i) Total CD4 and CD8 counts before and during ART.

There were no statistically significant differences in pre-ART CD4+ T lymphocyte counts between groups S, D, and F (Fig. 2; Tables 2 and 3). However, total CD4+ T lymphocyte counts during continuous ART at the time point of analysis were significantly higher in groups D and S than in group F (Fig. 2; Tables 2 and 3). Total CD8 counts were similar in groups S and D and were at lower levels, although not statistically significant, in group F (Fig. 2).

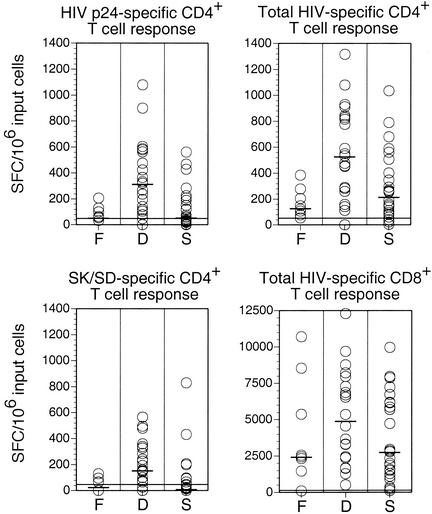

(ii) HIV-specific CD4+ T lymphocyte responses.

The magnitude of HIV-specific CD4+ T lymphocyte responses was determined directly ex vivo by IFN-γ ELISPOT analysis. In each case, PBL were isolated from a fresh blood sample and depleted of CD8+ T lymphocytes before stimulation with a comprehensive range of antigens derived from HIV-1. Strik-ingly, the most prominent HIV-specific CD4+ T lymphocyte responses were observed in group D (Fig. 4). The magnitude of the HIV-specific CD4+ T lymphocyte response was significantly larger in group D than in either group F or group S (Table 6).

FIG. 4.

Antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocyte responses. HIV-specific CD4+ T lymphocyte responses determined by IFN-γ ELISPOT analysis with CD8-depleted PBL are shown in the upper two panels. In the upper left panel, HIV p24 Gag-specific frequencies in CD8+ T lymphocyte-depleted PBL are shown. For each patient, the sum of CD4+ T lymphocyte frequencies specific for all HIV-derived antigens tested within CD8+ T lymphocyte-depleted PBL is shown in the upper right panel. In the lower left panel, frequencies of CD4+ T lymphocytes specific for the HIV-unrelated antigens SK/SD within CD8+ T cell-depleted PBL are shown. The lower right panel shows frequencies of HIV-specific CD8+ T cells as determined by IFN-γ ELISPOT analysis. Pooled overlapping peptides spanning HIV Env, RT, p24 Gag, p17 Gag, Nef, Tat, and Rev were used for stimulation of PBL, and for each patient, the sum of the responses to the individual peptide pools is represented by a circle. This approach strictly measures both HIV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocyte responses; however, the HIV-specific CD4+ T lymphocyte responses observed in this study were more than 1 order of magnitude lower than the corresponding HIV-specific CD8+ T lymphocyte responses and did not impact on the statistical analysis presented (Table 6). Each circle represents a mean of two measurements from an individual patient. Bars indicate median values. Lines represent the detection limits of the experiments.

TABLE 6.

Comparison of T-cell responses of patient groups by Mann-Whitney U test (CI, 95%)

| Type of T-cell response |

P value for comparison of groups:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| F and D | F and S | D and S | |

| HIV p24-specific CD4+ | 0.0005 | 0.21 | 0.0044 |

| HIV-specific CD4+ | 0.0001 | 0.077 | 0.008 |

| SK- and SD-specific CD4+ | 0.0009 | 0.30 | 0.041 |

| HIV-specific CD8+ | 0.50 | 0.77 | 0.13 |

To evaluate the durability of the CD4+ T cell response to p24 gag, we reassayed seven patients at an interval of 5 to 11 months (median, 9 months) after the first assay. Comparison of the HIV-specific CD4+ ELISPOT assays showed a mean of 604 SFCs initially and 365 at the time of the second assay (this difference is not significant by two-tailed t test). This result confirms that the responses are stable and not transient.

No significant differences in the size of HIV-specific CD4+ T lymphocyte responses were observed between groups F and S (Table 6). The frequency of CD4+ T lymphocytes specific for the HIV-unrelated recall antigens SK and SD was significantly higher in group D than in the other two groups (Fig. 4; Table 6).

(iii) HIV-specific CD8+ T lymphocyte responses.

The magnitude of HIV-specific CD8+ T lymphocyte frequencies was assessed in all patients by direct ex vivo IFN-γ ELISPOT analysis. For each patient, the total HIV-specific CD8+ T lymphocyte response was determined as the sum of individual responses to a comprehensive range of peptide pools spanning seven virus-derived proteins (Fig. 4). Although not reaching statistical significance, the total HIV-specific CD8+ T lymphocyte response in group D patients tended to be higher than those in group S and F patients (Table 6).

DISCUSSION

Virologic failure on continuous ART is associated with two clinically distinct outcomes. In the great majority of cases, peripheral CD4+ T lymphocyte counts decrease in conjunction with a resurgence of plasma virus (group F). This pattern of virologic failure is associated with a disadvantageous clinical outcome. In the minority of cases (approximately 5%), peripheral CD4+ T lymphocyte counts remain stable or continue to increase despite ongoing virus replication and the recrudescence of measurable pVL (group D). These patients exhibit a discordance between HIV-1 RNA pVL and total CD4+ T lymphocyte count (6, 15, 18, 25, 27). The aim of this study was to identify virologic or immunologic correlates of these distinct biological outcomes in the presence of continuous ART.

The likely reason for virologic failure on continuous ART, assuming that therapeutic levels of individual antiretroviral agents in plasma are maintained, is the emergence of drug-resistant virus strains (13). In both groups F and D, sequence analysis of plasma HIV-1 RNA demonstrated that the majority of circulating virus sequences contained multiple mutations within RT and PR that confer antiretroviral drug resistance (Table 4). There was no significant difference between the number of resistance mutations in the D and F groups, nor any significant association with any point mutations between the two groups. This observation indicates that virologic failure is associated with drug-resistant virus independent of the clinical outcome and suggests that inadequate dosing or poor compliance with prescribed therapy were not determinant factors in distinguishing groups F and D. It was not possible to isolate viruses from any group D plasma samples; this is most likely due to the relatively low virus loads compared to those of group F. Recombinant viruses were generated instead from plasma pol sequences. Our studies with these recombinant viruses demonstrated that these drug resistance mutations conferred no substantial differences in viral growth kinetics between groups F and D (Fig. 3). It has recently been reported that drug-resistant virus shows impaired replication in the thymus, thus potentially contributing to the preservation of CD4+ T cell counts in patients with virologic rebound on therapy (30). However, the observation that drug-resistant mutations were prevalent in both groups F and D suggests that additional factors contribute to the differential clinical outcome; in this light, comparative thymocyte infectivity assays would be of considerable interest. Plasma virus could not be sequenced from patients in group S, as pVL was too low for satisfactory amplification.

It has been suggested that viral strains of HIV-1 which use the CXCR4 coreceptor are more cytopathic than strains which use the CCR5 coreceptor. Thus, the F group patients might represent those in whom a switch from CCR5- to CXCR4-using viruses had occurred, leading to more rapid loss of CD4 cells. We tested the idea that viral tropism could explain the different clinical outcomes of virologic failure by performing a sequence analysis of the C2V3 Env region amplified from circulating HIV-1 that allows the assignment of an inferred biologic phenotype (11, 12). This analysis demonstrated that in both groups D and F, the dominant viral strains in most cases used predominantly the CCR5 coreceptor (Table 5). The absence of distinct viral tropism differences between groups D and F argues against differential CD4 cytopathogenicity resulting from divergent patterns of HIV-1 coreceptor usage. We therefore assessed whether immunological differences could distinguish the outcome of virologic failure.

No statistically significant differences in pre-ART total CD4+ T lymphocyte counts were observed between groups F, D, and S (Fig. 2; Tables 2 and 3). However, according to the definition of the groups, total CD4+ T lymphocyte counts were significantly higher on ART in groups D and S than in group F. It has been reported that the total CD4+ T lymphocyte count in patients with virological failure correlates positively with thymic output of naïve CD4+ T lymphocytes. This, in turn, correlates negatively with age (18). These factors are controlled in our study population, as all three groups are age matched.

Direct ex vivo analysis of HIV-specific CD4+ T lymphocyte frequencies demonstrated that the magnitude of this response in group D was significantly higher than in either group F or group S. A similar intergroup pattern was observed for total HIV-specific CD8+ T lymphocyte frequencies, although these differences were not statistically significant (Fig. 4; Table 6). There are several potential explanations for these findings. First, the differences in pVL between groups F and D could be a consequence of the more robust HIV-specific cellular immune response in the latter group. There is substantial evidence that the HIV-specific CD8+ T lymphocyte response is central to the control of virus replication, and emerging evidence favors a similar role for the HIV-specific CD4+ T lymphocyte response (26, 28, 29). It should also be noted that group D patients exhibited significantly stronger CD4+ T lymphocyte responses to SK and SD than group F patients (Fig. 4; Table 6); this might reflect a generally more robust cellular immune system which could have a bearing on the observed phenotypic differences between the two groups. Second, HIV-specific CD4+ T lymphocytes could serve as a reservoir for viral amplification through preferential infection. Thus, the generally higher frequencies of HIV-specific CD4+ T cells within group D than within group S could potentially serve as viral production sites. Over a certain threshold of viral replication, perhaps as occurs in group F patients, such reservoirs might become depleted (8). Third, the differences in magnitude of the HIV-specific cellular immune responses between the three groups could simply reflect the differences in pVL. In this scenario, HIV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocyte responses are determined by the balance between antigenic drive and virus-induced destruction, while pVL is fixed by unrelated factors. Group D could therefore maintain higher frequencies of HIV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes than group S due to the presence of more stimulating antigen and higher frequencies than group F due to excessive destruction and/or impaired production of these cells in this latter group (8, 26, 28, 31, 34).

The finding that significantly higher levels of HIV-specific CD4+ T lymphocytes characterize group D than group F identifies a clear correlate of clinical outcome in patients with virologic failure on continuous ART. In contrast to this immunological distinction, virologic studies indicated the almost uniform presence of drug-resistant R5 virus in both groups F and D. It has been reported that drug-resistant virus is less replication competent than wild-type HIV-1 (2, 6, 20) and shows impaired replication in human thymic cells (30). The slower replication kinetics of such viral strains might allow enhanced immunological control in the presence of cellular immune responses above a certain threshold. In the absence of HIV-specific cellular immune responses, even virus with impaired replication kinetics could recrudesce to pre-ART levels, unrestrained by host immunity. It is attractive to speculate that continuous ART, which favors resistant viruses with impaired replication capacity, and a potent specific cellular immune response which can be maintained in the absence of more virulent strains jointly contribute to a favorable clinical outcome despite virologic failure. Consistent with this interpretation, it has recently been demonstrated that reversion to wild-type virus after discontinuation of ART in patients with virologic failure and discordant total CD4+ T lymphocyte counts, analogous to group D in this study, is associated with substantial increases in pVL and a reduction in total CD4+ T lymphocyte counts (6). Crucially, in the present study, we showed that the CD4+ responses were sustained when patients were reassayed. After a median of 9 months, there was no difference in the SFC numbers reactive to p24 gag. These data dispel the notion that the responses we describe here are transient.

In summary, the cross-sectional data presented here identify clear immunologic correlates of the discordant response to virologic failure. Interpretation of the cause of this association will require further longitudinal studies.

Acknowledgments

D.A.P., G.S., and A.O. contributed equally to this work.

This work was supported by the Medical Research Council (D.A.P.), the Swiss National Foundation (A.O.), the Wellcome Trust (R.E.P., S.A.B., R.B., J.N.W.), and the Multiple Sclerosis Society of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (G.E.J.); D.A.P. is a Medical Research Council Clinician Scientist. Peptides were provided by the EU program EVA/MRC Centralized Facility for AIDS Reagents, NIBSC (grant numbers QLK2-CT-1999-00609 and GP828102).

We thank Will Reece for statistical advice.

REFERENCES

- 1.Autran, B., G. Carcelain, T. S. Li, C. Blanc, D. Mathez, R. Tubiana, C. Katlama, P. Debre, and J. Leibowitch. 1997. Positive effects of combined antiretroviral therapy on CD4+ T cell homeostasis and function in advanced HIV disease. Science 277:112-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berkhout, B. 1999. HIV-1 evolution under pressure of protease inhibitors: climbing the stairs of viral fitness. J. Biomed. Sci. 6:298-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boucher, C. A., W. Keulen, T. van Bommel, M. Nijhuis, D. de Jong, M. D. de Jong, P. Schipper, and N. K. Back. 1996. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 drug susceptibility determination by using recombinant viruses generated from patient sera tested in a cell-killing assay. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2404-2409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carpenter, C. C., M. A. Fischl, S. M. Hammer, M. S. Hirsch, D. M. Jacobsen, D. A. Katzenstein, J. S. Montaner, D. D. Richman, M. S. Saag, R. T. Schooley, M. A. Thompson, S. Vella, P. G. Yeni, and P. A. Volberding. 1997. Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in 1997. Updated recommendations of the International AIDS Society-USA panel. JAMA 277:1962-1969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chun, T. W., L. Stuyver, S. B. Mizell, L. A. Ehler, J. A. Mican, M. Baseler, A. L. Lloyd, M. A. Nowak, and A. S. Fauci. 1997. Presence of an inducible HIV-1 latent reservoir during highly active antiretroviral therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:13193-13197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deeks, S. G., T. Wrin, T. Liegler, R. Hoh, M. Hayden, J. D. Barbour, N. S. Hellmann, C. J. Petropoulos, J. M. McCune, M. K. Hellerstein, and R. M. Grant. 2001. Virologic and immunologic consequences of discontinuing combination antiretroviral-drug therapy in HIV-infected patients with detectable viremia. N. Engl. J. Med. 344:472-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delwart, E. L., H. W. Sheppard, B. D. Walker, J. Goudsmit, and J. I. Mullins. 1994. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 evolution in vivo tracked by DNA heteroduplex mobility assays. J. Virol. 68:6672-6683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Douek, D. C., J. M. Brenchley, M. R. Betts, D. R. Ambrozak, B. J. Hill, Y. Okamoto, J. P. Casazza, J. Kuruppu, K. Kunstman, S. Wolinsky, Z. Grossman, M. Dybul, A. Oxenius, D. A. Price, M. Connors, and R. A. Koup. 2002. HIV preferentially infects HIV-specific CD4+ T cells. Nature 417:95-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Egger, M., B. Hirschel, P. Francioli, P. Sudre, M. Wirz, M. Flepp, M. Rickenbach, R. Malinverni, P. Vernazza, M. Battegay, et al. 1997. Impact of new antiretroviral combination therapies in HIV infected patients in Switzerland: prospective multicentre study. BMJ 315:1194-1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finzi, D., M. Hermankova, T. Pierson, L. M. Carruth, C. Buck, R. E. Chaisson, T. C. Quinn, K. Chadwick, J. Margolick, R. Brookmeyer, J. Gallant, M. Markowitz, D. D. Ho, D. D. Richman, and R. F. Siliciano. 1997. Identification of a reservoir for HIV-1 in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Science 278:1295-1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fouchier, R. A., M. Brouwer, S. M. Broersen, and H. Schuitemaker. 1995. Simple determination of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 syncytium-inducing V3 genotype by PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:906-911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fouchier, R. A., M. Groenink, N. A. Kootstra, M. Tersmette, H. G. Huisman, F. Miedema, and H. Schuitemaker. 1992. Phenotype-associated sequence variation in the third variable domain of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 molecule. J. Virol. 66:3183-3187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirsch, M. S., B. Conway, R. T. D'Aquila, V. A. Johnson, F. Brun-Vezinet, B. Clotet, L. M. Demeter, S. M. Hammer, D. M. Jacobsen, D. R. Kuritzkes, C. Loveday, J. W. Mellors, S. Vella, D. D. Richman, et al. 1998. Antiretroviral drug resistance testing in adults with HIV infection: implications for clinical management. JAMA 279:1984-1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirschel, B., and P. Francioli. 1998. Progress and problems in the fight against AIDS. N. Engl. J. Med. 338:906-908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaufmann, D., G. Pantaleo, P. Sudre, A. Telenti, et al. 1998. CD4-cell count in HIV-1-infected individuals remaining viraemic with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). Lancet 351:723-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelleher, A. D., A. Carr, J. Zaunders, and D. A. Cooper. 1996. Alterations in the immune response of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected subjects treated with an HIV-specific protease inhibitor, ritonavir. J. Infect. Dis. 173:321-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lalvani, A., R. Brookes, S. Hambleton, W. J. Britton, A. V. Hill, and A. J. McMichael. 1997. Rapid effector function in CD8+ memory T cells. J. Exp. Med. 186:859-865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lecossier, D., F. Bouchonnet, P. Schneider, F. Clavel, and A. J. Hance. 2001. Discordant increases in CD4+ T cells in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients experiencing virologic treatment failure: role of changes in thymic output and T cell death. J. Infect. Dis. 183:1009-1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li, T. S., R. Tubiana, C. Katlama, V. Calvez, H. Ait Mohand, and B. Autran. 1998. Long-lasting recovery in CD4 T-cell function and viral-load reduction after highly active antiretroviral therapy in advanced HIV-1 disease. Lancet 351:1682-1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Markowitz, M. 2000. Resistance, fitness, adherence, and potency: mapping the paths to virologic failure. JAMA 283:250-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maschera, B., E. Furfine, and E. D. Blair. 1995. Analysis of resistance to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease inhibitors by using matched bacterial expression and proviral infection vectors. J. Virol. 69:5431-5436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mellors, J. W., C. R. Rinaldo, Jr., P. Gupta, R. M. White, J. A. Todd, and L. A. Kingsley. 1996. Prognosis in HIV-1 infection predicted by the quantity of virus in plasma. Science 272:1167-1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oxenius, A., D. A. Price, P. J. Easterbrook, C. A. O'Callaghan, A. D. Kelleher, J. A. Whelan, G. Sontag, A. K. Sewell, and R. E. Phillips. 2000. Early highly active antiretroviral therapy for acute HIV-1 infection preserves immune function of CD8+ and CD4+ T lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:3382-3387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palella, F. J., Jr., K. M. Delaney, A. C. Moorman, M. O. Loveless, J. Fuhrer, G. A. Satten, D. J. Aschman, S. D. Holmberg, et al.. 1998. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 338:853-860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perrin, L., and A. Telenti. 1998. HIV treatment failure: testing for HIV resistance in clinical practice. Science 280:1871-1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Picker, L. J., and V. C. Maino. 2000. The CD4(+) T cell response to HIV-1. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 12:381-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piketty, C., P. Castiel, L. Belec, D. Batisse, A. Si Mohamed, J. Gilquin, G. Gonzalez-Canali, D. Jayle, M. Karmochkine, L. Weiss, J. P. Aboulker, and M. D. Kazatchkine. 1998. Discrepant responses to triple combination antiretroviral therapy in advanced HIV disease. AIDS 12:745-750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenberg, E. S., J. M. Billingsley, A. M. Caliendo, S. L. Boswell, P. E. Sax, S. A. Kalams, and B. D. Walker. 1997. Vigorous HIV-1-specific CD4+ T cell responses associated with control of viremia. Science 278:1447-1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sewell, A. K., D. A. Price, A. Oxenius, A. D. Kelleher, and R. E. Phillips. 2000. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses to human immunodeficiency virus: control and escape. Stem Cells 18:230-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stoddart, C. A., T. J. Liegler, F. Mammano, V. D. Linquist-Stepps, M. S. Hayden, S. G. Deeks, R. M. Grant, F. Clavel, and J. M. McCune. 2001. Impaired replication of protease inhibitor-resistant HIV-1 in human thymus. Nat. Med. 7:712-718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Veazey, R. S., I. C. Tham, K. G. Mansfield, M. DeMaria, A. E. Forand, D. E. Shvetz, L. V. Chalifoux, P. K. Sehgal, and A. A. Lackner. 2000. Identifying the target cell in primary simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection: highly activated memory CD4(+) T cells are rapidly eliminated in early SIV infection in vivo. J. Virol. 74:57-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Volberding, P. A., and S. G. Deeks. 1998. Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection: promises and problems. JAMA 279:1343-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong, J. K., M. Hezareh, H. F. Gunthard, D. V. Havlir, C. C. Ignacio, C. A. Spina, and D. D. Richman. 1997. Recovery of replication-competent HIV despite prolonged suppression of plasma viremia. Science 278:1291-1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu, X. N., G. R. Screaton, F. M. Gotch, T. Dong, R. Tan, N. Almond, B. Walker, R. Stebbings, K. Kent, S. Nagata, J. E. Stott, and A. J. McMichael. 1997. Evasion of cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses by nef-dependent induction of Fas ligand (CD95L) expression on simian immunodeficiency virus-infected cells. J. Exp. Med. 186:7-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang, C., D. Pieniazek, S. M. Owen, C. Fridlund, J. Nkengasong, T. D. Mastro, M. A. Rayfield, R. Downing, B. Biryawaho, A. Tanuri, L. Zekeng, G. van der Groen, F. Gao, and R. B. Lal. 1999. Detection of phylogenetically diverse human immunodeficiency virus type 1 groups M and O from plasma by using highly sensitive and specific generic primers. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2581-2586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]