Abstract

Streptococcus pneumoniae is one of the few species within the group of low-G +C gram-positive bacteria reported to contain no d-alanine in teichoic acids, although the dltABCD operon encoding proteins responsible for d-alanylation is present in the genomes of two S. pneumoniae strains, the laboratory strain R6 and the clinical isolate TIGR4. The annotation of dltA in R6 predicts a protein, d-alanine-d-alanyl carrier protein ligase (Dcl), that is shorter at the amino terminus than all other Dcl proteins. Translation of dltA could also start upstream of the annotated TTG start codon at a GTG, resulting in the premature termination of dltA translation at a stop codon. Applying a novel integrative translation probe plasmid with Escherichia coli ′lacZ as a reporter, we could demonstrate that dltA translation starts at the upstream GTG. Consequently, S. pneumoniae R6 is a dltA mutant, whereas S. pneumoniae D39, the parental strain of R6, and Rx, another derivative of D39, contained intact dltA genes. Repair of the stop codon in dltA of R6 and insertional inactivation of dltA in D39 and Rx yielded pairs of dltA-deficient and dltA-proficient strains. Subsequent phenotypic analysis showed that dltA inactivation resulted in enhanced sensitivity to the cationic antimicrobial peptides nisin and gallidermin, a phenotype fully consistent with those of dltA mutants of other gram-positive bacteria. In addition, mild alkaline hydrolysis of heat-inactivated whole cells released d-alanine from dltA-proficient strains, but not from dltA mutants. The results of our study suggest that, as in many other low-G+C gram-positive bacteria, teichoic acids of S. pneumoniae contain d-alanine residues in order to protect this human pathogen against the actions of cationic antimicrobial peptides.

Teichoic acids (TAs) are polymers with a relatively wide structural diversity that are present at the surfaces of many gram-positive bacteria (18). The most common types of TAs are comprised of either polyglycerol phosphate or polyribitol phosphate chains of variable length that are substituted with glycosyl residues or d-alanyl esters, or both. TAs may be covalently linked to peptidoglycan (wall teichoic acids [WTAs]) or anchored in the cytoplasmic membrane by their glycolipid moiety (lipoteichoic acids [LTAs]). As major constituents of the surfaces of gram-positive bacteria, TAs have an impact on a number of important biological processes, such as autolysis (60), binding of cations (25) and surface-associated proteins (9, 29), adhesion (1, 61), biofilm formation (21), coaggregation (13), resistance to antimicrobial agents (50, 51), protein secretion (46), acid tolerance (7), stimulation of immune response (20, 41), and virulence (1, 14, 52). In most of these processes, the degree of d-alanylation of TAs has been shown to be of outstanding importance. Addition of d-alanine to TAs reduces the negative charge of the cell envelope, thereby influencing the binding and interaction of various compounds. Incorporation of d-alanine in LTAs is accomplished in a two-step reaction involving d-alanine-d-alanyl carrier protein ligase (Dcl) and d-alanyl carrier protein (Dcp), gene products of dltA and dltC, respectively (15, 22, 23, 45). Two other genes of the dlt operon, dltB and dltD, encode proteins that are also required for d-alanylation of LTAs. DltD functions in the selection of the carrier protein Dcp for ligation with d-alanine (16), while DltB is proposed to be involved in the secretion of d-alanyl-Dcp (44). After transfer of d-alanine from Dcp to LTA, d-alanine may be incorporated into WTAs by transacylation. The dltABCD genes are present in all genome sequences of low-G+C bacteria determined so far.

TAs of Streptococcus pneumoniae and some strains of the closely related Streptococcus mitis have a rather unique and more complex tetrasaccharide-ribitol repeat structure consisting of d-glucose, the aminosugar 2-acetamido-4-amino-2,4,6-trideoxy-d-galactose, two N-acetyl-galactosaminyl residues substituted by phosphocholine, and ribitol-5-phosphate (4, 6, 19, 28, 30, 35). The repeat units are joined by phosphodiester bonds between ribitol and glycosyl residues. The degree of phosphocholine substitution and N-acetylation of galactosamine appears to be variable (6, 28, 30, 35), and glucose may be replaced by galactose in some strains (58). No d-alanylation was detected in TAs of S. pneumoniae, in contrast to the TAs of many other low-G+C gram-positive bacteria (44). Surprisingly, the dlt operon encoding proteins required for d-alanylation of TAs is present in the genomes of the two sequenced S. pneumoniae strains, the laboratory strain R6 and the clinical isolate TIGR4 (24, 57). Microarray experiments have indicated that the operon is expressed and regulated by the two-component regulatory system CiaRH (39).

In this communication, we show that the laboratory strain R6 is a dltA mutant. In addition, we demonstrate that the dlt operon is normally functional in other S. pneumoniae strains and confers resistance to the antimicrobial peptides nisin and gallidermin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, growth conditions, DNA manipulations, and transformation.

The S. pneumoniae strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Plasmid constructions were carried out in Escherichia coli DH5α [λ− φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK−) supE44 thi-1 gyrA relA1]. Plasmid pBR322 (56) was used to construct the shuttle vector pKL1 and the integrative translation probe plasmid pTP1. The origin of replication for S. pneumoniae in the shuttle vector originated from plasmid pPR1 (55). Plasmid pEVP3 (12) served as the source for spoVG′-′lacZ gene fusion. The truncated ′lacZ gene was isolated from plasmid pRB274lac (10). Plasmid pUC18 (62) was generally applied for cloning. S. pneumoniae strains were grown at 37°C without aeration in C medium (36) supplemented with 0.2% yeast extract. Growth was monitored by nephelometry. DNA manipulations, plasmid DNA isolation, transformation of E. coli, and preparation of media and agar plates for E. coli were done by standard procedures (54). Sequencing was performed using an ABI Prism 3100 automated sequencer. PCR for cloning was carried out with Vent DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs). Transformation of S. pneumoniae was carried out as described previously (38).

TABLE 1.

S. pneumoniae strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant characteristicsa | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| R6 | dltA* (TAG at codon 20) | 47 |

| R6dlt+ | dltA (CAG at codon 20) | This work |

| R6Δdlt | dltA::ermAM | This work |

| D39 | dltA | 3 |

| D39Δdlt | dltA::ermAM | This work |

| Rx | dltA | 53 |

| RxΔdlt | dltA::ermAM | This work |

Only the dlt genotype is indicated.

RNA isolation and determination of the dltA transcriptional start site.

To isolate total RNA from S. pneumoniae, the cells were grown in C medium to a density of 40 nephelometry units (NU) and harvested by centrifugation. RNA was extracted using an RNeasy Midi Kit (QIAGEN) according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

The transcriptional start point of dltA was determined by rapid amplification of cDNA ends essentially as described previously (2, 5). Fifteen micrograms of total cellular RNA was incubated with 25 units tobacco acid pyrophosphatase (Epicenter Technologies) in the delivered buffer at 37°C for 60 min in the presence of 40 units SUPERaseIN RNase inhibitor (Ambion). In parallel, another 15-μg aliquot of RNA was incubated under the same conditions without tobacco acid pyrophosphatase. Both reaction mixtures were phenol-chloroform extracted and ethanol precipitated. RNA pellets were resuspended in 55 μl diethyl pyrocarbonate-H2O (Ambion), mixed with 500 pmol RNA adapter (5′-GAUAUGCGCGAAUUCCUGUAGAACGAACACUAGAAGAAA-3′) obtained from Biomers GmbH, and heat denatured at 95°C for 5 min. Ligation of the adapter was carried out at 17°C overnight with 100 units T4 RNA ligase (New England Biolabs) in the delivered buffer in the presence of 80 units SUPERaseIN (Ambion) in a total reaction volume of 100 μl. The reaction mixtures were again phenol-chloroform extracted and ethanol precipitated. The pellet was resuspended in 25 μl diethyl pyrocarbonate-H2O (Ambion). Five microliters of this ligated RNA was reverse transcribed with a dltA-specific primer (positions 1973863 to 1973882 in the R6 genome sequence) using the 1st Strand cDNA synthesis kit for reverse transcription-PCR (avian myeloblastosis virus) (Roche) according to the instructions of the manufacturer in a volume of 20 μl. Two microliters of the cDNA was amplified by PCR using another dltA primer immediately adjacent to the first one and a primer complementary to the RNA adapter sequence. PCR was performed using 5 units of Goldstar Red Taq Polymerase (Eurogentec) for 40 cycles at an annealing temperature of 50°C. The PCR product was analyzed on a 2% agarose gel, and the DNA sequence of the resulting fragment was determined. The transcriptional start site of dltA is depicted in Fig. 1.

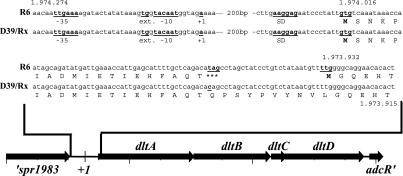

FIG. 1.

Genetic organization of the dltA operon in S. pneumoniae R6, D39, and Rx. The organization of the dltA operon is shown in the orientation opposite to its location on the chromosome. The nucleotide sequences of the dltA promoter region and the 5′ region of the dltA open reading frame are shown. Promoter sequences (−35 and extended [ext.] −10), putative Shine-Dalgarno Sequences (SD), start and stop codons, and the transcriptional start point are shown in boldface and are underlined. The positions of the depicted sequences in the genome of S. pneumoniae R6 and the positions of the alternative start codons are indicated.

Construction of the translation probe plasmid pTP1.

The translation probe plasmid pTP1 was constructed with pBR322 as the basic vector for cloning in E. coli. To allow integration into the genome of S. pneumoniae R6, the region of the endogenous β-galactosidase gene bgaA was chosen. Two fragments of this region, one inside of bgaA and the other upstream of bgaA, were produced by PCR using primers bga-blunt, bga-SalI, 0564-EcoRI, and 0564-NheI. The blunt-SalI ′bgaA′ fragment covered 849 bp inside bgaA (positions 577905 to 578754 in R6), and the EcoRI-NheI ′spr0564 fragment covered 833 bp at the 3′ end of spr0564 (positions 570894 to 571826) upstream of bgaA (Fig. 2). The fragments were successively cloned into pBR322 cut with EcoRI and NheI and with SalI and PvuII, respectively. Subsequently, the EcoRI recognition sequence was eliminated by fill in to aid further cloning. Into the resulting plasmid, a tetracycline resistance gene, tetM from Streptococcus mitis B6 (33), was cloned as an NheI fragment in the orientation shown in Fig. 2A. The tetM fragment was obtained from pUC18-tetM containing a modified fragment where an EcoRI restriction site upstream of the resistance gene had been removed by mutagenesis. This integrative tetracycline resistance plasmid then served to receive the spoVG′-′lacZ gene from the promoter probe plasmid pEVP3. This fragment was integrated as a BglII-DraI fragment into the tetM plasmid cut with BamHI and PvuII, which is located at the beginning of the ′bgaA′ fragment. The plasmid obtained in this way was designated pPP1. It is an integrative promoter probe plasmid for S. pneumoniae and may serve to analyze transcriptional regulation in the organism.

FIG. 2.

Translational fusions of dltA to E. coli ′lacZ. (A) Genetic map of the integrative translation probe plasmid pTP1. The nucleotide sequence of the multiple cloning site is shown. Authentic amino acids of β-galactosidase are highlighted in boldface. To construct translational fusions to ′lacZ, HindIII or BamHI may be used. (B) Genetic organization of the bgaA region in S. pneumoniae R6. The wild-type region of bgaA is shown, along with the same region after insertion of the translation probe plasmid pTP1. Upon integration, the endogenous bgaA gene is disrupted, and box, one of the two repetitive elements (box and rupA), is deleted. (C) Nucleotide sequence of dltA′-′lacZ fusions. Only relevant parts of the fusions are shown. The dltA promoter, which is present on all plasmids, is not shown. The Shine-Dalgarno sequence (SD) and start and stop codons are shown in boldface and are underlined. Amino acids encoded by dltA that are present in the fusion protein are underlined. Amino acids of β-galactosidase are indicated in boldface.

To convert the promoter probe plasmid into a translation probe plasmid, the BamHI-EcoRV fragment of spoVG′-′lacZ was replaced by the corresponding ′lacZ fragment of plasmid pRB274lac, removing the translational start site of spoVG′-′lacZ. In the resulting translation probe plasmid pTP1, the truncated ′lacZ gene starts with the ninth codon and lacks translation initiation signals (Fig. 2). Therefore, production of β-galactosidase requires a promoter and translation initiation signals, including a start codon fused in frame to the truncated ′lacZ. Due to a stop codon in the multiple cloning site (Fig. 2), only HindIII and BamHI may be used for lacZ fusions.

Construction of dltA′-′lacZ fusions.

To determine the translational start site of dltA, primers dltTTG (CGGGATCCTGCCCCAAAACATTATAG) and dltGTG (CGGGATCCGGTTTATTTGACACAATAGGG) were used with primer dltAfor (GCGGCATGCTACTGAGAGTTTTGGTATTAG), located upstream of the dltA promoter, to produce SphI-BamHI fragments from S. pneumoniae R6 DNA, fusing dltA′ to ′lacZ of pTP1 downstream of the TTG or GTG codon (Fig. 1 and 2C). The plasmids pDLTA(TTG) and pDLTA(GTG) were obtained in E. coli, and the dltA′ insertions were sequenced to ensure correct fusion to ′lacZ. S. pneumoniae R6 was transformed with the plasmids, and the transformants were selected with tetracycline (3 μg/ml). Correct integration by double crossover was confirmed by PCR and DNA sequencing. The strains were designated S. pneumoniae RT2 (dltA′(GTG)-′lacZ) and RT3 (dltA′(TTG)-′lacZ).

Determination of β-galactosidase activity.

To determine β-galactosidase activity in cell extracts of S. pneumoniae, cells were grown in C medium to a cell density of 80 to 90 NU. After centrifugation, the cells were resuspended in Z buffer (40), and cell lysis was achieved by adding Triton X-100 to a final concentration of 0.05% and incubation for 5 min at 37°C. The cell extracts were kept on ice and assayed for β-galactosidase activity at 30°C using 0.8 mg/ml o-nitrophenol-β-d-galactopyranoside. Release of nitrophenol was recorded at 420 nm for 20 to 30 min. Specific β-galactosidase activities are expressed in nanomoles of nitrophenol released per minute per milligram of protein. Protein concentrations were determined by the method of Bradford (8). The β-galactosidase activities determined in this study are summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

β-Galactosidase activities expressed from dltA′-′lacZ gene fusions in S. pneumoniae R6 derivatives

| Straina | Gene fusionb | β-Galactosidase activityc (nmol nitrophenol produced/min/mg of protein) |

|---|---|---|

| RT1 | —′lacZ | <1 |

| RT2 | dltA′(GTG)-′lacZ | 44.6 |

| RT3 | dltA′(TTG)-′lacZ | <1 |

All strains are derivatives of R6 and are deficient in endogenous β-galactosidase activity due to the disruption of the bgaA locus.

Gene fusions were integrated at the bgaA locus: bgaA::tetM-′lacZ.

Mean values of three independent cultures are presented. The standard deviations did not exceed ±15%. Strains were grown in C medium to the late exponential growth phase, and 5 ml of the culture was assayed for β-galactosidase activity.

Insertional inactivation of dltA.

To inactivate dltA in the genome of S. pneumoniae, the ermAM resistance gene (37) was fused to PCR fragments originating upstream and inside of dltA by overlapping PCR using 5′-CCGCCGCGGCAGGCCGCCGC and 3′-CGACGACGACGACGACGACGA tags, respectively. The fragments for homologous recombination covered 712 bp inside dltA, produced by primers dltI1 (positions 1972995 to 1973014 in S. pneumoniae R6) and dltI2 (1973707 to 1973687), and 780 bp upstream of dltA and partially inside the preceding spr1983 using primers dltU1 (1974988 to 1974968) and dltU2 (1974208 to 1974226). Primers dltI2 and dltU2 had the corresponding tags to integrate ermAM in the same orientation as dltA. The resulting spr1983′-ermAM-′dltA PCR fragment was introduced into S. pneumoniae strains R6, D39, and Rx, and the transformants were selected on D agar supplemented with 3% sheep blood and erythromycin (1 μg/ml). Correct integration was confirmed by PCR and DNA sequencing. The resulting strains were designated R6ΔdltA (dltA::ermAM), D39ΔdltA (dltA::ermAM), and RxΔdltA (dltA::ermAM) (Table 1); 190 bp upstream of dltA and 309 bp at the 3′ end of dltA, including the translation initiation region and GTG start codon, were replaced in these strains. Therefore, the dltA gene product Dcl was no longer produced.

Construction of an S. pneumoniae-E. coli shuttle vector harboring dltA.

To construct an S. pneumoniae-E. coli shuttle vector, the BamHI-PvuII fragment of pBR322 harboring the origin of replication and the β-lactamase gene was fused to an HpaI-BamHI fragment containing the single- and double-strand origin of the small, cryptic S. pneumoniae plasmid pPR1. This fragment was obtained from a pUC18-pPR1 chimerical plasmid that contained the whole pPR1 linearized with PstI. Into this plasmid, pBR322-PR1, the tetracycline resistance gene from pUC18-tetM was cloned as an NheI fragment to yield pKL1. The dltA gene was amplified with chromosomal D39 DNA as a template and primers Dlt3 (1975118 to 1975093) and Dlt4 (1972844 to 1972867) covering 1,100 bp upstream of dltA and 1,173 bp inside the gene. Both primers contained BamHI restriction sites at their ends, and the dltA fragment was inserted into the unique BamHI site of pKL1. The resulting plasmid was designated pKL-dltA.

Replacement of dltA::ermAM with dltA by gene conversion.

By gene conversion (11, 27), an allele of a gene cloned on a replicative plasmid may be integrated into the genome after transformation and subsequent homologous recombination, thereby replacing the chromosomal copy of the respective gene. To be able to repair the stop codon in dltA* (see below) of R6, R6ΔdltA was used as the recipient for transformation with plasmid pKL-dltA. The resulting transformants were screened for loss of erythromycin resistance, which should be indicative of the introduction of dltA into the genome. Two erythromycin-sensitive colonies were obtained among 140 transformants that were tested. Both contained the dltA gene without a stop codon. After the plasmid was cured, one of the colonies was taken for further analysis. Transformants were selected with tetracycline (5 μg/ml) on D blood agar plates. Subsequently, the colonies were streaked on D blood agar plates with erythromycin (1 μg/ml) to screen for sensitive transformants. Two clones out of 140 were not able to grow on erythromycin-containing plates. The corresponding colonies from agar plates without antibiotic were grown twice in liquid culture without any selection, plated on D blood agar plates, and screened for the presence of the plasmid by testing tetracycline resistance; 85% of the colonies were tetracycline sensitive, indicating curing of the plasmid. The dltA genes from these two colonies were amplified by PCR, and the DNA sequences were determined. In both genes, the TAG stop codon had reverted to the wild-type CAG sense codon. Thus, dltA was now intact in these strains. One colony was taken for further study and designated R6dlt+.

Determination of MICs of nisin and gallidermin.

To determine susceptibility to the antimicrobial peptides nisin and gallidermin, S. pneumoniae strains were grown in C medium to a cell density of 70 NU. These exponentially growing cultures were diluted in fresh medium to yield about 5 NU. In this medium, various concentrations, in steps of 0.1 μg/ml, of nisin (Sigma-Aldrich) or gallidermin (Genmedics GmbH) were present. Growth at 37°C was monitored for 8 h. The MIC for nisin or gallidermin was defined as the concentration allowing at most one doubling within the time of the experiment. Growth experiments were repeated three to five times. Values obtained three times in these experiments were taken as MICs and are listed in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Susceptibility of dltA-proficient and dltA-deficient S. pneumoniae strains to nisin and gallidermin

| Strain | Relevant genotypea | MICb (μg/ml)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Nisin | Gallidermin | ||

| R6dlt+ | dltA | 6 | 0.8 |

| R6 | dltA* | 3 | 0.5 |

| D39 | dltA | 4 | 0.4 |

| D39Δdlt | dltA::ermAM | 0.6 | 0.3 |

| Rx | dltA | 1 | 0.3 |

| RxΔdlt | dltA::ermAM | 0.2 | 0.2 |

Only the dlt genotype is indicated.

MICs were determined in liquid culture by diluting logarithmically growing cells into fresh medium containing various concentrations of the antimicrobial substances. Subsequently, growth was monitored by nephelometry. The results of three independent experiments are presented. The variation in MIC determination was ±0.1 μg/ml of the indicated substance.

Alkaline hydrolysis of heat-inactivated whole cells.

S. pneumoniae strains were grown in C medium to a cell density of 90 NU. Three hundred milliliters of the cells was pelleted by centrifugation, washed twice with ammonium acetate buffer (20 mM; pH 4.7), and resuspended in 1 ml of the same buffer. The cells were inactivated by incubation at 100°C for 10 min. To avoid loss of released d-alanine, the cells were not centrifuged but lyophilized. Ten milligrams of the dried cells was resuspended in 150 μl 0.1 N NaOH and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. After neutralization with 0.1 N HCl, the cells were removed by centrifugation and the supernatant was lyophilized.

Quantification of d-alanine by HPLC.

The dried supernatant from 10 mg cells was used for precolumn derivatization with Marfey's reagent (1-fluoro-2,4-dinitrophenyl-5-l-alanine amide; Sigma) as described previously (32). Marfey's reagent reacts with the optical isomers of amino acids to form diastereomeric N-aryl derivatives, which can be separated by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The separation of the amino acid derivatives (detection at 340 nm) was accomplished using a C18 reversed-phase column (Hypersil ODS; 3 μm; 125 mm by 4.6 mm; Bischoff Chromatography, Leonberg, Germany) on a Beckman-Coulter HPLC system at 30°C with a flow rate of 1 ml per min by linear gradient elution from 0 to 50% acetonitrile in sodium acetate buffer (20 mM; pH 4) in 10 min, followed by 3 min of isocratic elution at 50% acetonitrile in sodium acetate buffer (20 mM; pH 4). The d-Ala derivatives showed a linear relationship between the amount injected and the peak area in the range of 50 to 1,000 pmol.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences of pPP1 and pTP1 are available from GenBank (accession numbers DQ431184 and DQ431185, respectively).

RESULTS

Genetic organization of the dltABCD operon in S. pneumoniae R6.

Despite the reported lack of d-alanine in TAs of S. pneumoniae, the laboratory S. pneumoniae strain R6 has all four genes of the dlt operon in its genome (24). The genetic organization of R6 (Fig. 1) is identical to those of all dlt operons sequenced so far, and the deduced proteins show a high degree of similarity to Dlt proteins. However, Dcl, the gene product of the first gene, dltA, is only 488 amino acids (aa) in length, while the Dcl proteins of other bacteria consist of more than 500 aa. Protein comparisons indicated that Dcl(R6) is missing approximately 25 N-terminal residues. Closer inspection of the dltA sequence indicated that dltA could start at a GTG located at position 1974016 (Fig. 1) rather than at the annotated TTG further downstream at position 1973932 (Fig. 1). The GTG is preceded by a putative ribosome binding site, whereas upstream of the TTG, no sequence complementary to 16S rRNA is present. The open reading frame starting at this GTG, however, is interrupted by an amber stop codon, resulting in a small protein of only 19 aa, which are similar to the N-terminal residues of Dcl proteins. Thus, the laboratory strain R6 produces either a Dcl protein truncated at the N terminus or, due to the stop codon, only a short Dcl peptide.

Determination of the translational start of dltA using a novel integrative translation probe plasmid.

To be able to determine the translational start site of dltA and to assess if S. pneumoniae R6 is a dltA mutant, an integrative translation probe plasmid (pTP1) was developed (Fig. 2A). This plasmid allowed cloning of promoter regions, including translational start sites, to drive expression of the promoterless β-galactosidase gene (′lacZ) of Escherichia coli, which is also missing translation initiation signals and the first eight codons of ′lacZ. Translational fusions are directed by homologous recombination to the S. pneumoniae bgaA locus encoding endogenous β-galactosidase (Fig. 2B). Upon integration by double crossover, most of the bgaA gene is deleted and the background β-galactosidase level is eliminated (Table 2).

Two translational fusions were constructed with the dltA gene. Both contained the dltA promoter, whose transcriptional start point had been determined by rapid amplification of cDNA ends, and different parts of the dltA coding regions. In pDLTA(GTG), five codons starting with GTG (1.974.016) were fused to ′lacZ, yielding dltA′(GTG)-′lacZ, while in pDLTA(TTG), the fusion gene dltA′(TTG)-′lacZ started with TTG (1.973.932), followed by the next two codons of dltA (Fig. 2C). Both fusions were integrated at the bgaA locus in the chromosome of S. pneumoniae R6 to yield the strains RT2 and RT3. In addition, ′lacZ on pTP1 without expression signals was integrated as a control (strain RT1). As shown in Table 2, a β-galactosidase activity of 44 U was measured in strain RT2 harboring the dltA′(GTG)-′lacZ gene fusion, but in strain RT3 with the downstream TTG as a start codon, no β-galactosidase activity was detectable. These results clearly demonstrate, first, that dltA translation starts at GTG (1.974.016) and is efficiently interrupted by the stop codon and, secondly, that the TTG annotated as the dltA start codon in the R6 genome sequence does not function as such. Therefore, S. pneumoniae R6 constitutes a dltA mutant. The dltA gene interrupted by an amber codon is designated dltA* below.

Nucleotide sequence of the dltABCD operons of S. pneumoniae D39 and Rx.

S. pneumoniae R6 has a long history as a laboratory strain (47) and is derived from S. pneumoniae D39 (3). Another derivative of D39, S. pneumoniae Rx, is also a common laboratory strain (53). To determine if the stop codon in dltA is present in both of these strains, the nucleotide sequences of the whole dlt operons of D39 and Rx were determined. The dltA sequence of D39 differed from that of R6 in one position: the T of the TAG amber codon was replaced by C, specifying glutamine. Strain Rx also had CAG instead of TAG at that position. Thus, in both strains, the dltA gene was intact, encoding a Dcl protein of 516 aa. The point mutation inactivating dltA apparently occurred only in R6. In Rx, two other point mutations were detected, a C-to-T transition in the untranslated region of dltA 146 bp upstream of the GTG start codon and another C-to-T mutation at the wobble position of a cysteine codon in dltD. Both mutations do not appear to alter the expression or function of the dlt operon.

Construction of isogenic dlt mutant strains.

Since the dltA gene is intact in S. pneumoniae D39 and Rx, it was of interest to determine if inactivation of dltA would lead to a detectable phenotype in these strains. For that purpose, an erythromycin resistance gene was placed at the beginning of dltA, concomitantly deleting dltA translation initiation signals. After integration of this construct into the genomes of D39 and Rx, the dltA-deficient strains D39Δdlt and RxΔdlt were obtained.

To be able to compare the phenotypic consequences of an intact dltA in the R6 background, the TAG stop codon within dltA* was repaired to CAG by gene conversion as described in Materials and Methods. The dltA-proficient R6 derivative obtained by this process was designated R6dlt+.

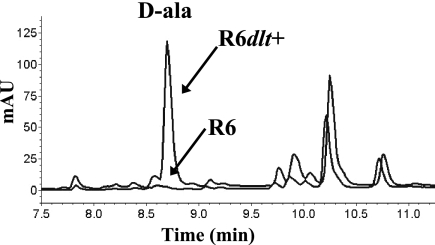

Detection of d-alanine released from dltA-proficient whole cells by alkaline hydrolysis.

d-Alanyl esters in TAs have been shown to be relatively labile at alkaline pH (44). Therefore, it should be possible to detect d-alanine liberated from whole cells by alkaline hydrolysis, as recently shown for group A streptococcus (34). To this end, heat-inactivated cells from the strains R6dlt+ and R6 were subjected to alkaline treatment, and the resulting supernatants were analyzed for the presence of d-alanine as described in Materials and Methods. As shown in Fig. 3, d-alanine was released in appreciable amounts from R6dlt+ cells but was virtually undetectable from R6. Quantifying d-alanine yielded 50 nmol released from 10 mg cells for R6dlt+, while the value for R6 was below detection level. Thus, a functional dlt operon results in the alkali-labile incorporation of d-alanine in molecules that are at the surfaces of S. pneumoniae cells. The most likely molecules to receive d-alanine from proteins of the dlt operon are LTA and WTA.

FIG. 3.

HPLC detection of d-alanine released from whole cells. Supernatants prepared by alkaline hydrolysis of S. pneumoniae R6 and R6dlt+ cells were derivatized with Marfey's reagent and separated by HPLC. Samples were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. The relevant part of the elution profile is shown. d-Alanine derivatives eluted at approximately 8.7 min. Their position is indicated (d-ala) and was determined by analyzing standards containing d-alanine (data not shown). mAU, milli-absorbance units.

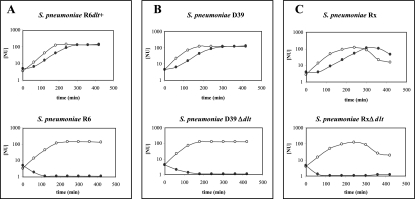

A functional dlt operon confers resistance to nisin and gallidermin.

To characterize the isogenic dlt mutant strains, their growth, morphological appearance, genetic competence, acid sensitivity, and autolysis were compared. Autolysis during stationary phase started earlier in dltA-deficient R6 and D39Δdlt but was unaffected in the Rx background. The other processes were not altered in the dltA mutant strains.

Since d-alanylation of TAs confers resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides in gram-positive bacteria, the three pairs of isogenic strains were tested for susceptibility to the lantibiotics nisin and gallidermin. As summarized in Table 3, inactivation of dltA in D39 and Rx significantly increased susceptibility to nisin. Accordingly, restoring dltA expression by removal of the stop codon in R6 reduced susceptibility (Table 3). MICs for the dltA-proficient strains varied, with R6dlt+ being most resistant. Loss of dltA function resulted in a twofold decrease of the MIC to nisin in R6, a fivefold reduction in Rx, and more than a sixfold drop in D39. The effect of a functional dltA on gallidermin susceptibility was less pronounced than for nisin but, at least for R6, significant (Table 3).

In Fig. 4, growth curves of the isogenic pairs are presented after treatment with nisin concentrations determined to be the MICs. Under these conditions, the dltA-proficient strains showed a decreased growth rate but reached the same cell density as the untreated culture, while dltA-deficient strains lysed virtually completely within 2 hours. These results clearly demonstrate that a functional dltA, and thus a functional dlt operon, confers resistance to positively charged antimicrobial peptides in S. pneumoniae, a phenotype also observed in other gram-positive bacteria.

FIG. 4.

Growth inhibition by nisin of S. pneumoniae dltA-proficient and dltA-deficient strains. Shown is the growth of isogenic strains treated with nisin concentrations determined to be the MIC of the dltA-deficient strain. The cells were grown in C medium. Cell density was monitored by nephelometry and is shown as NU. Typical growth curves to determine the MIC of nisin are shown. (A) Growth of isogenic S. pneumoniae R6 dltA pairs. Growth without added nisin is shown by open circles. Growth in the presence of a final concentration of 3 μg nisin per ml is shown by filled circles. (B) Growth of isogenic S. pneumoniae D39 dltA pairs. Growth without added nisin is shown by open circles. Growth in the presence of a final concentration of 0.6 μg nisin per ml is shown by filled circles. (C) Growth of isogenic S. pneumoniae Rx dltA pairs. Growth without added nisin is shown by open circles. Growth in the presence of a final concentration of 0.2 μg nisin per ml is shown by filled circles.

The genetically related strains showed surprising differences in nisin susceptibility that were not dependent on dltA (Table 3). Their major difference, the presence or absence of a capsule, cannot account for the various resistance levels, since the most and the least resistant strains, R6dlt+ and Rx, respectively, do not possess a capsule, while D39 is encapsulated. Other mutations must be responsible for the observed differences.

DISCUSSION

By use of a novel integrative translation probe plasmid, the translational start site of dltA could be assigned to a GTG upstream of the annotated TTG start codon. In addition, it became clear that the TTG does not serve to start dltA translation. Consequently, in S. pneumoniae R6, a C-terminally truncated Dcl protein of only 19 amino acids is produced, but not an N-terminally truncated form, as suggested by the annotation. A similar problem with differently assigned translation start sites was reported recently for lytC in S. pneumoniae TIGR4 (43). Genome annotation suggested an inactivated gene, but biochemical analysis yielded active LytC protein. In this case, a later start of lytC translation could explain the discrepancy, although the start of translation was not determined in the study. The new translation probe plasmid pTP1 will be a useful tool for the determination of translational start points, and it will help to solve problems with annotations that are likely to occur with increasing genomic data. In addition, the system is well suited to analyze translational regulation in S. pneumoniae.

The identification of S. pneumoniae R6 as a dltA mutant and the phenotypic consequences of dltA inactivation in dltA-proficient S. pneumoniae strains shed new light on the structures of LTA and WTA in these bacteria. With dltA of R6 as the exception, all other dltA genes of seven S. pneumoniae strains whose sequences are currently available are intact (57) (http//www.sanger.ac.uk; http//www.tigr.org). Thus, a functional dltA appears to be part of the normal genetic repertoire of S. pneumoniae. Considering the phenotype of the loss of dltA function, increased sensitivity to cationic antimicrobial peptides, it is conceivable that S. pneumoniae strains need a functional dlt operon to cope with positively charged peptides of host innate immunity (48). In addition, it would be beneficial for competition with other bacteria occupying the same ecological niches.

The protective effect of d-alanylation of TAs is a consequence of partially neutralizing the negative charge of the anionic cell wall polymer by incorporation of positively charged residues. However, other cell surface modifications may also contribute to resistance to antimicrobial peptides. In S. pneumoniae, deacetylation of N-acetylglucosamine in peptidoglycan by PgdA (59) introduces positive charges into murein. In Staphylococcus aureus, lysinylation of anionic membrane lipids by MprF decreases the negative net charge of the cell surface (49). Thus, the interplay of several defense mechanisms may determine overall resistance to antimicrobial peptides, and the contributions of d-alanylation of TAs to resistance may vary considerably in different bacterial species (1, 46, 50, 52).

The similarity of the S. pneumoniae dlt operon to functionally well-characterized dlt operons from other bacteria, the phenotypes of the S. pneumoniae dltA mutants, and the detection of alkali-labile d-alanine in dltA-proficient strains are fully consistent with the assumption that TAs of this organism contain d-alanine. Structural studies of TAs of S. pneumoniae, however, did not reveal d-alanine as a constituent of WTA or LTA, leading to the assumption that TAs of S. pneumoniae strains in general do not contain d-alanine (17). However, only the structure of LTA and one structure of WTA have been determined in the dltA mutant R6, readily explaining the inability to detect d-alanine (4, 19). Assuming that the dlt operon is normally intact in S. pneumoniae, d-alanine could have been present in the WTAs from other S. pneumoniae strains but was also not detected (28, 30, 35, 58). Two reasons may account for the failure to detect d-alanine in these studies. First, d-alanine may be present in LTA but not in WTA. Second, and much more probable, d-alanyl esters are likely to be lost during preparation of WTA, in particular if cell walls are treated with hydrofluoric acid to release WTA repeating units from peptidoglycan. Even in LTA preparations, d-alanine substitutions may easily be lost (26, 41, 42). In a recent study analyzing LTA from an S. pneumoniae strain presumed to be dlt proficient, it was noted that different forms of LTAs were obtained, depending on the method of purification, but they were not analyzed in further detail (31). Considering the structure of the repeat unit of S. pneumoniae TAs, the hydroxyl groups of ribitol phosphate are the most likely candidates for d-alanylation (44). Clearly, new structural determinations of LTA and WTA are required to exactly determine the site(s) of d-alanylation and the number of d-alanine residues per molecule of LTA or WTA.

In conclusion, the results of our study strongly suggest that TAs of S. pneumoniae contain d-alanine substitutions. d-Alanylation helps to protect this important human pathogen from antimicrobial peptides.

ADDENDUM IN PROOF

A new structure of LTA of S. pneumoniae purified from strain Fp23, an unencapsulated mutant of TIGR4 containing an intact dlt operon, revealed the presence of d-alanine. LTA purified from strain R6, however, did not contain d-alanine (C. Draing, M. Pfitzenmaier, S. Zummo, G. Mancuso, A. Geyer, T. Hartung, and S. von Aulock, submitted for publication).

Acknowledgments

We thank F. C. Neuhaus and R. Süßmuth for stimulating discussions. We thank Gabriele Hornig and Katja Klöpper for their expert technical assistance.

Work in the laboratory of R.H. was supported in part by the EU (grant no. LSHM-CT-2003-503413), the Helmholtz Stiftung (grant no. 1800002_1), and the Schwerpunkt Biotechnology at the University of Kaiserslautern. Work in the laboratory of A.P. was supported by grants from the German Research Foundation (FOR449, GRK685, SPP1130, and SFB685), the European Union (LSHM-CT-2004-512093), and the German Ministry of Education and Research (NGFN2). W.V. was supported by the EU (LSHM-CT-2003-503413) and by the German Research Counsel (FOR449).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abachin, E., C. Poyart, E. Pellegrini, E. Milohanic, F. Fiedler, P. Berche, and P. Trieu-Cuot. 2002. Formation of d-alanyl-lipoteichoic acid is required for adhesion and virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. Mol. Microbiol. 43:1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Argaman, L., R. Hershberg, J. Vogel, G. Bejerano, E. G. Wagner, H. Margalit, and S. Altuvia. 2001. Novel small RNA-encoding genes in the intergenic regions of Escherichia coli. Curr. Biol. 11:941-950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avery, O. T., C. M. MacLeod, and M. McCarty. 1944. Studies on the chemical nature of the substance inducing transformation of pneumococcal types: induction of transformation by a desoxyribonucleic acid fraction isolated from pneumococcus type III. J. Exp. Med. 79:137-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Behr, T., W. Fischer, J. Peter-Katalinic, and H. Egge. 1992. The structure of pneumococcal lipoteichoic acid. Improved preparation, chemical and mass spectrometric studies. Eur. J. Biochem. 207:1063-1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bensing, B. A., B. J. Meyer, and G. M. Dunny. 1996. Sensitive detection of bacterial transcription initiation sites and differentiation from RNA processing sites in the pheromone-induced plasmid transfer system of Enterococcus faecalis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:7794-7799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergström, N., P. E. Jansson, M. Kilian, and U. B. Skov Sorensen. 2000. Structures of two cell wall-associated polysaccharides of a Streptococcus mitis biovar 1 strain. A unique teichoic acid-like polysaccharide and the group O antigen which is a C-polysaccharide in common with pneumococci. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:7147-7157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyd, D. A., D. G. Cvitkovitch, A. S. Bleiweis, M. Y. Kiriukhin, D. V. Debabov, F. C. Neuhaus, and I. R. Hamilton. 2000. Defects in d-alanyl-lipoteichoic acid synthesis in Streptococcus mutans results in acid sensitivity. J. Bacteriol. 182:6055-6065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:246-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Briese, T., and R. Hakenbeck. 1985. Interaction of the pneumococcal amidase with lipoteichoic acid and choline. Eur. J. Biochem. 146:417-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brückner, R., T. Dick, and H. Matzura. 1987. Dependence of expression of an inducible Staphylococcus aureus cat gene on the translation of its leader sequence. Mol. Gen. Genet. 207:486-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chak, K. F., H. de Lencastre, H. M. Liu, and P. J. Piggot. 1982. Facile in vivo transfer of mutations between the Bacillus subtilis chromosome and a plasmid harbouring homologous DNA. J. Gen. Microbiol. 128:2813-2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Claverys, J. P., A. Dintilhac, E. V. Pestova, B. Martin, and D. A. Morrison. 1995. Construction and evaluation of new drug-resistance cassettes for gene disruption mutagenesis in Streptococcus pneumoniae, using an ami test platform. Gene 164:123-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clemans, D. L., P. E. Kolenbrander, D. V. Debabov, Q. Zhang, R. D. Lunsford, H. Sakone, C. J. Whittaker, M. P. Heaton, and F. C. Neuhaus. 1999. Insertional inactivation of genes responsible for the d-alanylation of lipoteichoic acid in Streptococcus gordonii DL1 (Challis) affects intrageneric coaggregations. Infect. Immun. 67:2464-2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collins, L. V., S. A. Kristian, C. Weidenmaier, M. Faigle, K. P. Van Kessel, J. A. Van Strijp, F. Götz, B. Neumeister, and A. Peschel. 2002. Staphylococcus aureus strains lacking d-alanine modifications of teichoic acids are highly susceptible to human neutrophil killing and are virulence attenuated in mice. J. Infect. Dis. 186:214-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Debabov, D. V., M. P. Heaton, Q. Zhang, K. D. Stewart, R. H. Lambalot, and F. C. Neuhaus. 1996. The d-alanyl carrier protein in Lactobacillus casei: cloning, sequencing, and expression of dltC. J. Bacteriol. 178:3869-3876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Debabov, D. V., M. Y. Kiriukhin, and F. C. Neuhaus. 2000. Biosynthesis of lipoteichoic acid in Lactobacillus rhamnosus: role of DltD in d-alanylation. J. Bacteriol. 182:2855-2864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fischer, W. 2000. Pneumococcal lipoteichoic and teichoic acid, p. 155-177. In A. Tomasz (ed.), Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., Larchmont, N.Y.

- 18.Fischer, W. 1988. Physiology of lipoteichoic acids in bacteria. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 29:233-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fischer, W., T. Behr, R. Hartmann, J. Peter-Katalinic, and H. Egge. 1993. Teichoic acid and lipoteichoic acid of Streptococcus pneumoniae possess identical chain structures. A reinvestigation of teichoid acid (C polysaccharide). Eur. J. Biochem. 215:851-857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grangette, C., S. Nutten, E. Palumbo, S. Morath, C. Hermann, J. Dewulf, B. Pot, T. Hartung, P. Hols, and A. Mercenier. 2005. Enhanced antiinflammatory capacity of a Lactobacillus plantarum mutant synthesizing modified teichoic acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:10321-10326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gross, M., S. E. Cramton, F. Götz, and A. Peschel. 2001. Key role of teichoic acid net charge in Staphylococcus aureus colonization of artificial surfaces. Infect. Immun. 69:3423-3426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heaton, M. P., and F. C. Neuhaus. 1992. Biosynthesis of d-alanyl-lipoteichoic acid: cloning, nucleotide sequence, and expression of the Lactobacillus casei gene for the d-alanine-activating enzyme. J. Bacteriol. 174:4707-4717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heaton, M. P., and F. C. Neuhaus. 1994. Role of the d-alanyl carrier protein in the biosynthesis of d-alanyl-lipoteichoic acid. J. Bacteriol. 176:681-690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoskins, J., W. E. Alborn, Jr., J. Arnold, L. C. Blaszczak, S. Burgett, B. S. DeHoff, S. T. Estrem, L. Fritz, D. J. Fu, W. Fuller, C. Geringer, R. Gilmour, J. S. Glass, H. Khoja, A. R. Kraft, R. E. Lagace, D. J. LeBlanc, L. N. Lee, E. J. Lefkowitz, J. Lu, P. Matsushima, S. M. McAhren, M. McHenney, K. McLeaster, C. W. Mundy, T. I. Nicas, F. H. Norris, M. O'Garra, R. B. Peery, G. T. Robertson, P. Rockey, P. M. Sun, M. E. Winkler, Y. Yang, M. Young-Bellido, G. Zhao, C. A. Zook, R. H. Baltz, S. R. Jaskunas, P. R. Rosteck, Jr., P. L. Skatrud, and J. I. Glass. 2001. Genome of the bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae strain R6. J. Bacteriol. 183:5709-5717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hughes, A. H., I. C. Hancock, and J. Baddiley. 1973. The function of teichoic acids in cation control in bacterial membranes. Biochem. J. 132:83-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hurst, A., A. Hughes, M. Duckworth, and J. Baddiley. 1975. Loss of d-alanine during sublethal heating of Staphylococcus aureus S6 and magnesium binding during repair. J. Gen. Microbiol. 89:277-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iglesias, A., and T. A. Trautner. 1983. Plasmid transformation in Bacillus subtilis: symmetry of gene conversion in transformation with a hybrid plasmid containing chromosomal DNA. Mol. Gen. Genet. 189:73-76. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jennings, H. J., C. Lugowski, and N. M. Young. 1980. Structure of the complex polysaccharide C-substance from Streptococcus pneumoniae type 1. Biochemistry 19:4712-4719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jonquieres, R., H. Bierne, F. Fiedler, P. Gounon, and P. Cossart. 1999. Interaction between the protein InlB of Listeria monocytogenes and lipoteichoic acid: a novel mechanism of protein association at the surface of gram-positive bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 34:902-914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karlsson, C., P. E. Jansson, and U. B. Skov Sorensen. 1999. The pneumococcal common antigen C-polysaccharide occurs in different forms. Mono-substituted or di-substituted with phosphocholine. Eur. J. Biochem. 265:1091-1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim, J. H., H. Seo, S. H. Han, J. Lin, M. K. Park, U. B. Sorensen, and M. H. Nahm. 2005. Monoacyl lipoteichoic acid from pneumococci stimulates human cells but not mouse cells. Infect. Immun. 73:834-840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kochhar, S., and P. Christen. 1989. Amino acid analysis by high-performance liquid chromatography after derivatization with 1-fluoro-2,4-dinitrophenyl-5-l-alanine amide. Anal. Biochem. 178:17-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.König, A., R. R. Reinert, and R. Hakenbeck. 1998. Streptococcus mitis with unusually high level resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics. Microb. Drug. Resist. 4:45-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kristian, S. A., V. Datta, C. Weidenmaier, R. Kansal, I. Fedtke, A. Peschel, R. L. Gallo, and V. Nizet. 2005. d-Alanylation of teichoic acids promotes group A Streptococcus antimicrobial peptide resistance, neutrophil survival, and epithelial cell invasion. J. Bacteriol. 187:6719-6725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kulakowska, M., J. R. Brisson, D. W. Griffith, M. Young, and H. J. Jennings. 1993. High-resolution NMR spectroscopic analysis of the C-polysaccharide of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Can. J. Chem. 71:644-648. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lacks, S., and R. D. Hotchkiss. 1960. A study of the genetic material determining an enzyme in Pneumococcus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 39:508-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin, B., G. Alloing, V. Mejean, and J. P. Claverys. 1987. Constitutive expression of erythromycin resistance mediated by the ermAM determinant of plasmid pAM beta 1 results from deletion of 5′ leader peptide sequences. Plasmid 18:250-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mascher, T., M. Heintz, D. Zähner, M. Merai, and R. Hakenbeck. 2006. The CiaRH system of Streptococcus pneumoniae prevents lysis during stress induced by treatment with cell wall inhibitors and mutations in pbp2x involved in beta-lactam resistance. J. Bacteriol. 188:1959-1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mascher, T., D. Zähner, M. Merai, N. Balmelle, A. B. de Saizieu, and R. Hakenbeck. 2003. The Streptococcus pneumoniae cia regulon: CiaR target sites and transcription profile analysis. J. Bacteriol. 185:60-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 41.Morath, S., A. Geyer, and T. Hartung. 2001. Structure-function relationship of cytokine induction by lipoteichoic acid from Staphylococcus aureus. J. Exp. Med. 193:393-397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morath, S., A. Geyer, I. Spreitzer, C. Hermann, and T. Hartung. 2002. Structural decomposition and heterogeneity of commercial lipoteichoic acid preparations. Infect. Immun. 70:938-944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moscoso, M., E. Lopez, E. Garcia, and R. Lopez. 2005. Implications of physiological studies based on genomic sequences: Streptococcus pneumoniae TIGR4 synthesizes a functional LytC lysozyme. J. Bacteriol. 187:6238-6241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neuhaus, F. C., and J. Baddiley. 2003. A continuum of anionic charge: structures and functions of d-alanyl-teichoic acids in gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67:686-723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neuhaus, F. C., M. P. Heaton, D. V. Debabov, and Q. Zhang. 1996. The dlt operon in the biosynthesis of d-alanyl-lipoteichoic acid in Lactobacillus casei. Microb. Drug. Resist. 2:77-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nouaille, S., J. Commissaire, J. J. Gratadoux, P. Ravn, A. Bolotin, A. Gruss, Y. Le Loir, and P. Langella. 2004. Influence of lipoteichoic acid d-alanylation on protein secretion in Lactococcus lactis as revealed by random mutagenesis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:1600-1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ottolenghi, E., and R. D. Hotchkiss. 1962. Release of genetic transforming agent from pneumococcal cultures during growth and disintegration. J. Exp. Med. 116:491-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peschel, A. 2002. How do bacteria resist human antimicrobial peptides? Trends Microbiol. 10:179-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peschel, A., R. W. Jack, M. Otto, L. V. Collins, P. Staubitz, G. Nicholson, H. Kalbacher, W. F. Nieuwenhuizen, G. Jung, A. Tarkowski, K. P. van Kessel, and J. A. van Strijp. 2001. Staphylococcus aureus resistance to human defensins and evasion of neutrophil killing via the novel virulence factor MprF is based on modification of membrane lipids with l-lysine. J. Exp. Med. 193:1067-1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peschel, A., M. Otto, R. W. Jack, H. Kalbacher, G. Jung, and F. Götz. 1999. Inactivation of the dlt operon in Staphylococcus aureus confers sensitivity to defensins, protegrins, and other antimicrobial peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 274:8405-8410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peschel, A., C. Vuong, M. Otto, and F. Götz. 2000. The d-alanine residues of Staphylococcus aureus teichoic acids alter the susceptibility to vancomycin and the activity of autolytic enzymes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2845-2847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Poyart, C., E. Pellegrini, M. Marceau, M. Baptista, F. Jaubert, M. C. Lamy, and P. Trieu-Cuot. 2003. Attenuated virulence of Streptococcus agalactiae deficient in d-alanyl-lipoteichoic acid is due to an increased susceptibility to defensins and phagocytic cells. Mol. Microbiol. 49:1615-1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ravin, A. W. 1959. Reciprocal capsular transformations of pneumococci. J. Bacteriol. 77:296-309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual., 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 55.Schuster, C., M. van der Linden, and R. Hakenbeck. 1998. Small cryptic plasmids of Streptococcus pneumoniae belong to the pC194/pUB110 family of rolling circle plasmids. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 164:427-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sutcliffe, J. G. 1979. Complete sequence of Escherichia coli plasmid pBR322. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 43:77-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tettelin, H., K. E. Nelson, I. T. Paulsen, J. A. Eisen, T. D. Read, S. Peterson, J. Heidelberg, R. T. DeBoy, D. H. Haft, R. J. Dodson, A. S. Durkin, M. Gwinn, J. F. Kolonay, W. C. Nelson, J. D. Peterson, L. A. Umayam, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, M. R. Lewis, D. Radune, E. Holtzapple, H. Khouri, A. M. Wolf, T. R. Utterback, C. L. Hansen, L. A. McDonald, T. V. Feldblyum, S. Angiuoli, T. Dickinson, E. K. Hickey, I. E. Holt, B. J. Loftus, F. Yang, H. O. Smith, J. C. Venter, B. A. Dougherty, D. A. Morrison, S. K. Hollingshead, and C. M. Fraser. 2001. Complete genome sequence of a virulent isolate of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Science 293:498-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vialle, S., P. Sepulcri, J. Dubayle, and P. Talaga. 2005. The teichoic acid (C-polysaccharide) synthesized by Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 5 has a specific structure. Carbohydr. Res. 340:91-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vollmer, W., and A. Tomasz. 2000. The pgdA gene encodes for a peptidoglycan N-acetylglucosamine deacetylase in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Biol. Chem. 275:20496-20501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wecke, J., K. Madela, and W. Fischer. 1997. The absence of D-alanine from lipoteichoic acid and wall teichoic acid alters surface charge, enhances autolysis and increases susceptibility to methicillin in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 143:2953-2960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weidenmaier, C., J. F. Kokai-Kun, S. A. Kristian, T. Chanturiya, H. Kalbacher, M. Gross, G. Nicholson, B. Neumeister, J. J. Mond, and A. Peschel. 2004. Role of teichoic acids in Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization, a major risk factor in nosocomial infections. Nat. Med. 10:243-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yanisch-Perron, P., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]