Abstract

We have investigated the induction of protective mucosal immunity to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) isolate 89.6 by intranasal (i.n.) immunization of mice with gp120 and gp140 together with interleukin-12 (IL-12) and cholera toxin subunit B (CTB) as adjuvants. It was found that both IL-12 and CTB were required to elicit mucosal antibody responses and that i.n. immunization resulted in increased total, immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1), and IgG2a anti-HIV-1 antibody levels in serum; increased total, IgG1, IgG2a, and IgA antibody expression in bronchoalveolar lavage fluids; and increased IgA antibody levels in vaginal washes. Levels of anti-HIV-1 antibodies in both sera and secretions were higher in groups immunized with gp140 than in those immunized with gp120. However, only gp120-specific mucosal antibodies demonstrated neutralizing activity against HIV-1 89.6. Taken together, the results show that IL-12 and CTB act synergistically to enhance both systemic and local mucosal antibody responses to HIV-1 glycoproteins and that even though gp140 induces higher antibody titers than gp120, only gp120-specific mucosal antibodies interfere with virus infectivity.

Since the discovery of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in 1983 (5), tremendous financial and intellectual resources have been invested in the pursuit of effective drug treatments and vaccine strategies against the virus. However an effective vaccine for human use has yet to be found. HIV type 1 (HIV-1), like most other pathogens, primarily targets mucosal sites. Therefore, a vaccine that can elicit mucosal immunity may be an ideal candidate for prevention of HIV-1 infection.

Numerous reports have demonstrated an important role of neutralizing antibodies against HIV-1 for controlling infection (21, 27, 34). Virus-specific antibodies in blood can protect against systemic infection, whereas locally produced immunoglobulin A (IgA) could confer protection at the mucosal site of infection. The specific IgA content in mucosal secretions correlates with resistance to viruses (3, 23). Furthermore, studies on passive transfer of IgA support the immune barrier function attributed to this antibody isotype (7, 36, 41). A study by Mazzoli et al. (28) showed that mucosal HIV-specific IgA is present in urine and vaginal washes of individuals exposed to HIV. The same group, as well as others (11, 29), showed that mucosal and serum IgAs from HIV-exposed, seronegative individuals neutralize various HIV clades and that salivary IgA from HIV-1-infected patients is able to neutralize both in vitro-adapted and primary isolates of HIV-1 (30). More recently, it was shown that mucosal as well as systemic IgA from HIV-1-exposed, uninfected individuals directly interacts with HIV-1 and prevents its transcytosis across epithelial cells (1, 12). Numerous studies suggest that other antibody isotypes, especially murine IgG2a, are involved in protection against viral infections, although the immunological mechanisms have not been completely elucidated (10, 16, 46).

The envelope glycoprotein (Env) of HIV-1 is the principal antigen to which virus-neutralizing antibodies are directed, and Env will likely be included as a key component of a successful vaccine formula. Env is cleaved by host cell proteases into the gp120, external, and gp41 transmembrane subunits, which remain noncovalently associated. HIV-1 Env serves at least two functions that are critical in the life cycle of the virus: binding to cellular receptors (CD4 and coreceptors) and mediating the fusion of viral and cellular membranes during infection. Soluble, truncated forms of oligomeric HIV-1 Env, known as gp140, are comprised of the uncleaved gp120 and gp41 ectodomain subunits, while soluble gp120 Env formulations are monomeric. Since gp140 retains the oligomeric structure of the native Env, it is believed that this molecule may be a superior immunogen compared to gp120 for induction of neutralizing antibodies.

A variety of adjuvant systems have been employed to bolster the immunogenicity of subunit vaccines for HIV-1 as well as other viral antigens (44). In particular, it has been shown that interleukin-12 (IL-12) and cholera toxin subunit B (CTB) are highly effective vaccine adjuvants that can be delivered to mucosal sites to modulate both mucosal and systemic immunity to viral vaccines (3, 6, 9, 22).

The purpose of the present work was to characterize and compare the humoral immune responses to intranasal (i.n.) gp120 and gp140 immunization with IL-12 and CTB as adjuvants and to investigate the function of these antigen-specific antibodies in neutralization of HIV-1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Female BALB/c mice, 4 to 6 weeks of age, were purchased from Charles River Laboratory (Portage, Mich.) through the National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, Md.). Animals were maintained in filter top cages in Thoren units within the Animal Resource Facility at Albany Medical College. Food and water were provided ad libitum. All animal procedures conformed to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

Protein expression and purification.

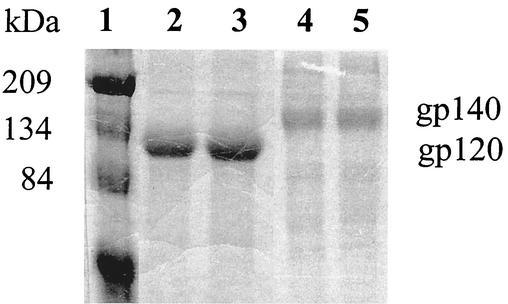

For Env expression, recombinant vaccinia viruses carrying the gp120 or gp140 Env genes from the 89.6 HIV-1 isolate were employed, and proteins were produced by infection of monolayers of BS-C-1 cells (ATCC CCL26) with recombinant vaccinia virus at a multiplicity of infection of 10 PFU/cell, as previously described (13) with some modification. The secreted Env was obtained by harvesting the medium (OPTI-MEM; Life Technologies, Inc., Rockville, Md.) after 30 h of infection. Envelope proteins were first affinity purified over lentil lectin-coupled Sepharose 4B (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) columns. Briefly, serum-free medium containing the glycoproteins was passed over the lentil lectin column at a rate of 4 ml/min by using a peristaltic pump (ISCO, Lincoln, Nebr.). The column was washed with two column volumes of 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5)-0.3 M NaCl-0.5% Triton X-100, followed by one column volume with the same buffer without Triton X-100. The proteins were eluted with 0.5 M methyl mannopyranoside (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4) and concentrated on Amicon Centriprep columns (MWCO 50 Kd) (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) to 1 to 2 ml. Oligomeric gp140 Env was separated from monomeric Env material by size exclusion chromatography with sterile, degassed PBS (pH 7.4) (Quality Biologic, Inc., Gaithersburg, Md.) by using a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 preparative-grade column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.) and an Amersham Pharmacia Biotech P-500 pump to achieve a constant flow rate of 90 ml/h, with a 1.5-MPa limit. After elution, the protein fractions were visualized on a colloidal Coomassie blue-stained (Novex, Carlsbad, Calif.) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel (Fig. 1). Protein was quantitated by image analysis with NIH Image version 1.62 by comparison to a previously prepared reference standard of IIIB gp120 purified under identical conditions and quantitated by amino acid analysis. All Env preparations were filter sterilized through a 0.22-mm-pore-size polyvinylidene difluoride low-protein-binding syringe filter (Millipore), stored at −80°C, and thawed once for use or storage at 4°C.

FIG. 1.

SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis of purified gp120 and gp140 glycoproteins. Proteins were electrophoresed on an SDS-5% polyacrylamide gel under reducing conditions, and the gel was stained with Coomassie blue. Lane 1, standard protein markers; lanes 2 and 3, gp120 (10 μg each); lanes 4 and 5, gp140 (5 μg each).

Immunizations and sample collection.

For i.n. immunizations, mice were first anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (Fort Dodge Laboratories, Fort Dodge, Iowa)-xylazine (Phoenix Scientific Inc., St. Joseph, Mo.). Mice were placed in a supine position, and 25 μl of vaccine was administered to the nostrils slowly, using a pipette tip. On day 0, mice received 1 or 5 μg of recombinant 89.6 gp120 or 89.6 gp140 in PBS containing 1% (vol/vol) normal BALB/c mouse serum alone or in combination with recombinant murine IL-12 (Genetics Institute, Cambridge, MA), and/or CTB (Sigma). Mice also received IL-12 on days 1, 2, and 3. Mice were boosted once on day 21 according to the same immunization protocol.

Blood was collected from the retro-orbital plexus of anesthetized mice, and the serum was stored at −20°C until use. Three days prior to vaginal wash collection, the mice were caged adjacent to male mice to synchronize their estrous cycle. Vaginal wash samples were collected by washing the vaginal cavities of anesthetized mice with 100 μl of sterile PBS. The resulting samples were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were stored at −20°C. On day 35 after vaccination, the mice were sacrificed by halothane inhalation (Halocarbon Laboratories, River Edge, N.J.), and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid was collected as previously described (2). The absence of blood contamination was confirmed by testing for serum albumin with albumin strips (Albusticks; Bayer Corporation, Elkhart, Ind.). The BAL fluids were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were stored at −20°C until further use.

Assessment of humoral immune responses.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used to quantitate levels of anti-gp120 or anti-gp140 antibodies in the sera, vaginal washes, and BAL fluids of immunized mice. Microtiter plates (Nalge Nunc International, Rochester, N.Y.) were coated overnight with 1 μg of recombinant soluble gp120 or gp140 per ml in PBS. The plates were washed with PBS containing 0.25% gelatin and 0.05% Tween 20 and blocked for 1 h at room temperature with PBS containing 1% gelatin. Serial dilutions of test samples were then added, and the plates were incubated overnight at 4°C. The plates were washed again and incubated with goat anti-mouse total Ig, IgG1, IgG2a, or IgA antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, Ala.) for 2 h at room temperature. The plates were then washed, p-nitrophenyl substrate (Sigma) was added, and color development at 405 nm was measured with a microplate reader (Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, Vt.). The serum antibody response is reported as titer values representing the reciprocal of the dilution equivalent to 25% of maximum binding. Due to sample dilution during collection, in some cases titers could not be determined for BAL fluids and vaginal washes. Therefore, the antibody responses in these samples are reported as optical density (OD) values.

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR.

Anesthetized mice were immunized i.n. with a single dose of gp120 either with or without IL-12 and CTB. Total RNA was isolated from spleen, lungs, lymph nodes, and vaginas plus uteruses of mice 48 h after immunization by using an RNA isolation kit (Ambion Inc., Austin, Tex.). The RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA, and real time PCR for gamma interferon (IFN-γ), IL-10, and IL-4 expression was conducted with an ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection system (Perkin-Elmer/Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) as previously described (35). The real-time PCR mixture consisted of 1 μg of cDNA, 3.5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM dATP, 200 μM dCTP, 200 μM dGTP, 400 μM dUTP, 0.3 μM sense and antisense primers, 0.2 μM target gene fluorogenic detection probe, 3.125 × 10−3 U of AmpliTaq Gold, and 2.5 × 10−3 U of AmpErase uracil N-glycosylase in a final volume of 25 μl. Each PCR amplification was performed in triplicate wells. PCR conditions consisted of 2 min at 50°C, 10 min at 94°C, and 40 cycles of amplification (15 s at 94°C and 1 min at 60°C). Each unknown cDNA sample was amplified simultaneously with known concentrations of plasmid DNAs encoding murine IFN-γ, IL-10, and IL-4 (provided by R. M. Locksley, University of California at San Francisco) (38).

Virus neutralization assay.

The virus neutralization assay was performed, essentially as previously described (32), with some modifications. Briefly, fourfold dilutions of HIV-1 isolate 89.6 (provided by the National Institutes of Health [NIH] AIDS Reagent Program), starting at 40 50% tissue culture infective doses (TCID50)/well (50 μl), were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with 50 μl of BAL fluid in a 96 well microtiter filtration plate. Each well then received 4 × 105 72-h phytohemagglutinin-stimulated human peripheral blood mononuclear cells in a total volume of 100 μl. HIV-1-positive wells were identified 14 days later by p24 assay (Coulter Corporation, Miami, Fla.), measuring the level of soluble p24 in accordance with the package insert. Culture wells were determined to be positive if the p24 levels were more than 30 pg/ml. The viral titer in the presence or absence of BAL fluid was calculated by the Spearman-Karber method. For a given dilution of BAL fluid, the TCID50s at day 14 were used to calculate the percentage of neutralization as follows: 100 − (Vn/V0 × 100), where Vn represents the TCID50 in the presence of BAL fluid and V0 represents the TCID50 in the absence of BAL fluid. Negative controls for this assay included wells containing normal BAL fluids collected from preimmune mice and wells containing medium in place of BAL fluid. As a positive control, the human monoclonal antibody 2G12 from the NIH AIDS Reagent Program was added to the virus prior to incubation with the peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

Statistical methods.

The Mann-Whitney U test was used to determine statistical significance. P values of <0.05 were considered significant. Only >75% neutralization as measured by the Spearman-Karber method was considered to be significant because of the fourfold virus dilutions utilized in the assay.

RESULTS

i.n. immunization induces a mixed Th1- and Th2-like phenotype.

Mice were i.n. immunized with gp120 in the presence of IL-12 or CTB or both, and 48 h later they were sacrificed and spleen, lungs, cervical lymph nodes, and vagina and uterus were isolated for real-time PCR analysis. It was found that i.n. immunization with gp120 plus IL-12 and with gp120 plus IL-12 plus CTB caused significant enhancement of IFN-γ mRNA expression in spleen, lungs, vaginal tract, and lymph nodes, as well as of IL-10 mRNA in spleen, vaginal tract, and lymph nodes, compared to mice treated with gp120 alone (P < 0.05) (Table 1). Of note were the high levels of IFN-γ mRNA detected in the genital tracts of mice receiving IL-12 or IL-12 and CTB with the vaccine. The induction of IFN-γ in genital tissue was four- to sevenfold more than that observed in the spleen and more than twice the levels observed in the lungs or lymph nodes. IL-10 message levels were lower than IFN-γ message levels in all tissues analyzed but tended to follow the same pattern of induction as IFN-γ. IL-4 message was significantly increased in the spleens and lungs of mice receiving gp120 plus CTB compared with mice receiving gp120 plus IL-12 or gp120 plus IL-12 plus CTB (P < 0.05). There was no detectable IL-4 in the genital tracts of any of the immunized groups. Thus, IL-12 and CTB as mucosal adjuvants induced a mixed Th1- and Th2-like immune response in both systemic and local compartments. Because the same results were obtained with mice inoculated with the adjuvants alone in the absence of gp120 (data not shown), we conclude that the observed cytokine induction is mediated by the IL-12 and CTB adjuvants.

TABLE 1.

Real-time PCR measurement of cytokine gene expression

| Cytokine | Tissue | Copy no. (105)a after immunization with:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gp120 | gp120 + IL-12 | gp120 + CTB | gp120 + IL-12 + CTB | ||

| IFN-γ | Spleen | 6.3 ± 3.2 | 40.2 ± 12.2∗ | 22.1 ± 13.2 | 75.4 ± 49.1∗ |

| Lung | 13.2 ± 9.4 | 147.0 ± 147.6∗ | 158.0 ± 162.6 | 112.0 ± 70.9∗ | |

| Vagina and uterus | 2.0 ± 0.8 | 302.0 ± 119.3∗ | 3.8 ± 2.6 | 291.0 ± 135.3∗ | |

| Lymph nodes | 3.4 ± 2.0 | 147.0 ± 139.7∗ | 4.6 ± 2.6 | 95.5 ± 39.4∗ | |

| IL-10 | Spleen | 3.1 ± 0.7 | 16.6 ± 10.3∗ | 7.0 ± 3.7 | 32.1 ± 16.3∗ |

| Lung | 3.6 ± 4.0 | 27.5 ± 19.4 | 15.8 ± 15.7 | 17.8 ± 9.2 | |

| Vagina and uterus | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 42.3 ± 23.4∗ | 0.6 ± 0.6 | 39.1 ± 17.4∗ | |

| Lymph nodes | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 51.9 ± 34.5∗ | 5.7 ± 6.1 | 45.0 ± 29.6∗ | |

| IL-4 | Spleen | 0.05 ± 0.03 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.08 ± 0.08∗ | 0.01 ± 0.00 |

| Lung | 0.02 ± 0.02 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.10 ± 0.08∗ | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| Vagina and uterus | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| Lymph nodes | 0.24 ± 0.08 | 0.12 ± 0.15 | 0.20 ± 0.20 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | |

Data are reported as means ± standard deviations for three mice per group. ∗P < 0.05 compared to gp120-only group.

i.n. vaccination induces a potent systemic and mucosal antibody response.

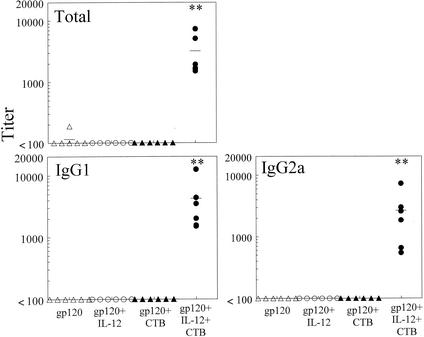

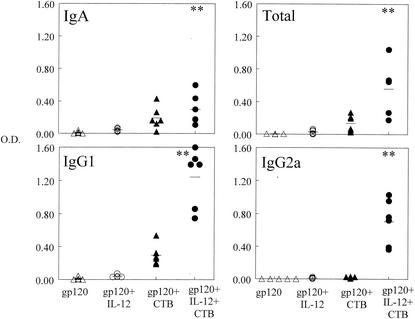

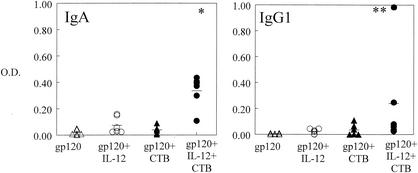

In order to determine if gp120 would induce a humoral immune response when administered i.n., mice were immunized on day 0 with gp120 with or without IL-12 and CTB and then boosted in a similar manner on day 21. Blood was collected on day 35 and analyzed for gp120-specific antibodies by ELISA. It was found that serum antibody titers in the group that received gp120 and both IL-12 and CTB were approximately 10-fold higher than those in the other three experimental groups (P < 0.05 for IgG2a and P < 0.005 for total antibody) (Fig. 2). Antigen-specific antibodies of the IgA isotype were also present but at very low levels (data not shown). Specificity was demonstrated by lack of binding to lysozyme-coated plates. Levels of specific antibodies in day 35 BAL fluids were also determined. It was found that levels of total, IgG1, IgG2a, and IgA antibodies were significantly enhanced by immunization with gp120 in the presence of IL-12 and CTB compared with the other experimental groups (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3). Finally, it was found that IgA in vaginal washes was induced in the group that received gp120, IL-12, and CTB but not in the gp120-only group or the group that was inoculated with gp120 plus CTB (P < 0.05). Antigen-specific IgG1 was also detected in the group that received gp120, IL-12, and CTB, but this was primarily observed in only one mouse (Fig. 4). These data show that after a single boost, i.n. administration of gp120 induces a potent systemic and local antibody response and the two mucosal adjuvants, IL-12 and CTB, act synergistically to enhance these responses.

FIG. 2.

Levels of serum gp120-specific antibodies in i.n. vaccinated mice. Sera were obtained from BALB/c mice 35 days after i.n. immunization with 5 μg of vaccine with or without 1 μg of IL-12 and 10 μg of CTB. Titers for individual mice are indicated by the symbols, and the average titer for each group is displayed as a line. Titers are expressed as the reciprocal serum dilutions corresponding to 25% maximal binding on the titration curve. Significant differences in antigen-specific antibody production were detected between the group immunized with gp120 plus IL-12 and CTB and all of the other groups (∗∗, P < 0.005). Pooled data from two experiments are shown.

FIG. 3.

Levels of gp120-specific antibodies in BAL fluids. BAL fluids were obtained from BALB/c mice 35 days after i.n. immunization with 5 μg of vaccine with or without 1 μg of IL-12 and 10 μg of CTB. Individual OD values are indicated by the symbols, and the average OD value for each group is displayed as a line. OD readings are the maximal values obtained from undiluted BAL fluid samples. Significant differences (∗∗, P < 0.005) in IgA production were detected between the group immunized with gp120 plus IL-12 and CTB and that immunized with gp120 as well as between the group immunized with gp120 plus IL-12 and CTB and that immunized with gp120 plus IL-12. Significant differences (∗∗, P < 0.005) in IgG1 and IgG2a production were detected between the group immunized with gp120 plus IL-12 and CTB and all of the other groups. Pooled data from two experiments are shown.

FIG. 4.

Levels of gp120-specific antibodies in vaginal washes. Vaginal washes were obtained from BALB/c mice 35 days after i.n. immunization with 5 μg of vaccine with or without 1 μg of IL-12 and 10 μg of CTB. Individual OD values are indicated by the symbols, and the average OD value for each group is displayed as a line. The values represent ODs obtained with 1:10 dilutions of vaginal wash samples. Significant differences (∗, P < 0.05) in IgA antibody production were detected between the group immunized with gp120 plus IL-12 and CTB and that immunized with gp120 as well as between the group immunized with gp120 plus IL-12 and CTB and that immunized with gp120 plus CTB. Significant differences in IgG1 antibody production were detected between the group immunized with gp120 plus IL-12 and CTB and that immunized with gp120 group (∗∗, P < 0.005) and between the group immunized with gp120 plus IL-12 and CTB and that immunized with gp120 plus IL-12 (∗, P < 0.05). Pooled data from two experiments are shown.

HIV-1 gp140 induces higher antibody titers than gp120.

Preliminary experiments demonstrated that i.n. administration of gp140 plus IL-12 and CTB also induced systemic and mucosal antibody responses. In order to compare gp120 and gp140 as mucosal immunogens, BALB/c mice were immunized i.n. with 1 or 5 μg of gp120 or gp140 in the presence of IL-12 and CTB, essentially as described above. On day 35, sera, BAL fluids, and vaginal washes were collected and analyzed for the presence of gp120- and gp140-specific antibodies by ELISA. At both doses and in all fluids analyzed, levels of antibodies were higher after gp140 immunization than after gp120 immunization (Fig. 5, 6, and 7). In fact, whereas 1 μg of gp140 induced antibody expression in both serum and BAL fluid, the same dose of gp120 was unable to generate antibody responses at those sites. While 5 μg of gp120 was immunogenic, it was still less effective than 5 μg of gp140 in generating antibody responses in serum, BAL fluid, and vaginal washes. Similar differences were observed when the antisera were tested against the nonhomologous antigen, i.e., when anti-gp120 sera were assayed on gp140-coated plates and anti-gp140 sera were assayed on gp120-coated plates (data not shown).

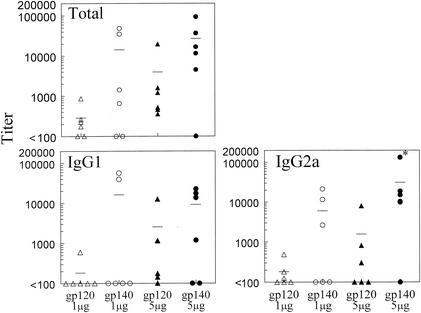

FIG. 5.

Comparison of gp120 and gp140 as mucosal immunogens for systemic immunity. Sera were obtained from BALB/c mice 35 days after i.n. immunization with 1 or 5 μg of gp120 or gp140 plus 1 μg of IL-12 and 10 μg of CTB. Titers for individual mice are indicated by the symbols, and the average titer for each group is displayed as a line. Titer values are expressed as the reciprocal serum dilutions corresponding to 25% maximal binding on the titration curve. The results show enhanced gp140-specific total, IgG1, and IgG2a antibodies in the sera of immune mice compared with gp120-specific antibody at both doses of antigens. For IgG2a antibody the difference is significant (∗, P < 0.05) at the 5-μg dose.

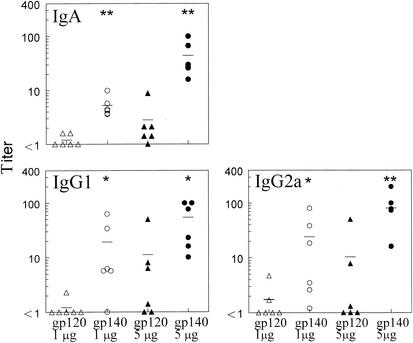

FIG. 6.

Comparison of gp120 and gp140 as mucosal immunogens for induction of lung antibodies. BAL fluids were obtained from BALB/c mice 35 days after i.n. immunization with 1 or 5 μg of gp120 or gp140 plus 1 μg of IL-12 and 10 μg of CTB. Titers for individual mice are indicated by the symbols, and the average titer for each group is displayed as a line. Titers are expressed as the reciprocal BAL dilutions corresponding to 25% maximal binding on the titration curve. The results show enhanced gp140-specific IgA (∗∗, P < 0.005), IgG1 (∗, P < 0.05), and IgG2a (∗, P < 0.05) antibodies in BAL fluids of immune mice compared with gp120-specific antibody at both doses of antigen.

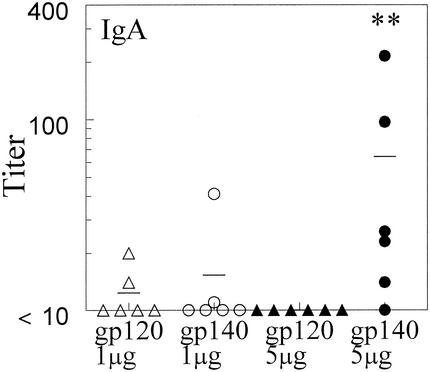

FIG. 7.

Comparison of gp120 and gp140 as mucosal immunogens for induction of antibodies in the genital compartment. Vaginal washes were obtained from BALB/c mice 35 days after i.n. immunization with 1 or 5 μg of gp120 or gp140 plus 1 μg of IL-12 and 10 μg of CTB. Titers for individual mice are indicated by the symbols, and the average titer for each group is displayed as a line. Titers are expressed as the reciprocal vaginal wash dilutions corresponding to 25% maximal binding on the titration curve. The results show that induction of gp140-specific mucosal IgA in vaginal washes is significantly greater than induction of gp120-specific IgA at 5 μg of antigen (∗∗, P < 0.005).

HIV-1 89.6 is neutralized by gp120- but not gp140-specific mucosal antibodies.

In order to investigate the potential neutralizing activity of gp120- and gp140-specific antibodies induced by mucosal immunization, the neutralization activity of immune BAL fluid from mice immunized with gp120 or gp140 plus IL-12 and CTB was tested. The neutralization activity was measured against the same HIV-1 isolate used to prepare the vaccine antigens. It was found that gp120-specific BAL fluid was neutralizing, and the neutralizing activity was proportional to the BAL fluid concentration (Table 2). The maximal amount of neutralization observed with BAL fluid was 75.5%. The highest level of neutralization (96.1%) was obtained with 20 μg of the standard 2G12 monoclonal antibody. Surprisingly, although gp140 induced higher antibody responses than gp120 when administered i.n., gp140-specific antibodies in BAL did not exhibit any neutralization activity. The small amount of neutralization activity exhibited by normal BAL fluid was not significant, as only values greater than 75% neutralization are considered significant in this assay.

TABLE 2.

Neutralizing antibodies generated by i.n. immunization with gp120 or gp140 plus IL-12 and CTB

| Sample | Sample dilution | % Neutralizationa |

|---|---|---|

| gp120 BAL fluid | 1:2 | 75.5 |

| 1:8 | 61.1 | |

| 1:32 | 0.0 | |

| gp140 BAL fluid | 1:2 | 0.0 |

| 1:8 | 0.0 | |

| 1:32 | 0.0 | |

| Normal BAL fluid | 1:2 | 37 |

| 2G12 monoclonal antibody | 1:50 | 96.1 |

| Medium | 0.0 |

Activity was determined in pooled BAL fluid obtained 2 weeks after the boost. Results are from a representative experiment out of three. Only neutralization of greater than 75% is considered significant in this assay.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that IL-12 and CTB administered i.n. act synergistically to enhance systemic and local antibody responses to HIV-1 gp120 and gp140. While gp140 was clearly superior as an immunogen, only gp120 elicited neutralizing antibodies against HIV-1 89.6 at mucosal surfaces.

Mucosal vaccination with gp120 or gp140 in the presence of IL-12 and CTB induced significant expression of HIV-specific IgG1 and IgG2a in serum and BAL fluid and of IgA antibody in BAL fluid and vaginal secretions. The presence of IgA in BAL fluid and vaginal secretions may be due to increased local IgA production by the antibody-secreting plasma cells that originated in the mucosal inductive sites and homed to the lung and vaginal tract. IFN-γ can enhance the expression of the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (39), including receptor expression on uterine cells (37), and thus increase transepithelial transport of IgA into mucosal surfaces. However, IFN-γ alone is not sufficient for enhanced anti-HIV antibody expression, since IL-12 by itself induced significant IFN-γ expression in the genital compartment yet mice immunized with vaccine plus IL-12 generated only a minimal IgA response. Significant levels of IgA antibody were obtained only in mice vaccinated in the presence of both IL-12 and CTB.

Our results are in agreement with findings of other groups that immunization at one mucosal surface results in the generation of antigen-specific antibodies at distant mucosal sites (15, 47). This is an important point because, if present in high titers, preexisting antibodies at the site of entry may prevent HIV-1 infection.

Comparison of gp120- and gp140-specific systemic and mucosal antibody responses showed that i.n. gp140 induced higher titers of antibodies in these compartments than gp120. This could be due to the fact that the oligomeric structure of gp140 is a determining factor in enhancing its immunogenicity, including the presence of additional epitopes from the gp41 fusion protein. However in an in vitro neutralization assay, BAL antibodies against gp140 failed to neutralize HIV-1 89.6 whereas BAL anti-gp120 antibodies were neutralizing. We also evaluated the neutralization activity of immune sera and vaginal washes, but the results were inconclusive due to high background levels. An explanation for the inability of mucosal anti-gp140 antibodies to neutralize HIV-1 may be the existence of dominant epitopes on gp120, which are obscured on the oligomer. In addition it has been shown that gp120 induces better anti-V3 loop neutralizing antibodies (25, 31). Alternatively, the induction of neutralizing antibodies by the gp140 immunogen may require a more aggressive immunization scheme. Now that we have established a model system that can bolster the level of a mucosal humoral response, future experiments will be aimed at designing an optimal immunization strategy capable of eliciting mucosal neutralizing antibody.

Others (14) have also found gp140 to be more immunogenic, but in addition they found it to induce stronger neutralization activity in rabbits and some degree of protection in rhesus macaques. However, it is difficult to compare their results with our data because of species differences and because of the fact that their experiments did not address the presence of neutralizing antibodies in mucosal secretions.

Previous work in our laboratory showed that i.n. coadministration of an influenza virus vaccine and IL-12 protected mice against influenza virus challenge and that this protection was antibody mediated. Protective IgA, IgG1, and IgG2a antibodies were induced in BAL fluid, while IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies were induced in serum after immunization with the influenza virus surface antigen and IL-12 (2). Vaccination strategies against HIV-1 involving cytokines or cytokine genes as adjuvants have been shown to bolster immune responses to this virus (45). Particularly, IL-12, due to its ability to promote type 1 cytokine responses and to enhance both cellular and humoral immunity, has been used as an adjuvant in numerous HIV-1 vaccine approaches (8, 17, 18, 24). A recent report showed that gp120 stimulates both humoral and cellular immunity to HIV-1 in rhesus macaques when administered with IL-12 (43). Although that study involved generation of high titers of anti-HIV-1 antibodies and potent neutralization activity, it used intramuscular immunization and thus did not address the induction of protective antibodies at mucosal sites.

Similarly, other investigators have shown that i.n. immunization of mice leads to the development of antigen-specific T cells and antibody-secreting cells in systemic and mucosal lymphoid tissues (4, 48), including induction of mucosal and systemic antibody responses against HIV-1 (19, 26, 40, 42). One of these studies used oligomeric gp160 and various adjuvants to show generation of neutralizing antibodies in serum and secretions (42). However, it did not explore the adjuvant activity of recombinant IL-12. Others have used IL-12 as a mucosal adjuvant for intrarectal immunization against HIV-1 peptides and were able to generate systemic and local cytotoxic responses, but those investigators did not examine induction of protective mucosal antibodies (6). Recently, Bradney et al. (9) used IL-12 coadministered with proinflammatory cytokines as adjuvants for anti-HIV i.n. immunization. Our results, in agreement with those of Bradney et al., demonstrated that no detectable antigen-specific antibodies were induced when IL-12 was used alone with the HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins. However, the addition of other adjuvants (IL-1 and IL-18 in the study by Bradney et al. or CTB in our case) were found to supply the signals necessary to generate systemic and mucosal antibody after i.n. immunization. One important difference between the studies is the fact that we immunized mice with whole gp120 protein or gp140 oligomer, whereas Bradney et al. used HIV synthetic peptides as immunogens, thus limiting the diversity of antibodies induced in the mice and also their ability to react with the native molecule.

It should be noted that in human cancer therapy trials, subcutaneous administration of IL-12 was found to be associated with significant toxicity (33). However, it has now been found that i.n. IL-12 inoculation results in much less toxicity than parenteral administration (20). Thus, i.n. vaccination may be a safe and efficacious approach for providing optimal protection against HIV-1 both systemically and at mucosal surfaces.

Several factors may have contributed to our findings. It is likely that the i.n. administered HIV-1 antigens were taken up by antigen-presenting cells in the nasal-associated lymphoid tissue, and the adjuvants provided signals for an efficient priming of resident naive T cells. In the local lymphoid microenvironment, IL-12 may have acted on T cells, whereas CTB may have activated antigen-presenting cells. This would explain why there was virtually no antibody response when gp120 or gp140 was coadministered with either one of the adjuvants alone. Once primed, T and B lymphocytes in the nasal-associated lymphoid tissue can migrate via the cervical lymph nodes to distant mucosal effector sites and mount systemic immune responses (49).

This study has revealed several interesting observations: the synergistic effect of IL-12 and CTB when administered i.n. with HIV-1 glycoproteins, the improved antibody response against gp140 compared with gp120, and finally, the induction of mucosal anti-HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies by i.n. immunization with gp120 vaccine together with IL-12 and CTB. Future studies will further determine the functions of these antibodies, as well as the cellular targets for the mucosal adjuvants and the mechanism by which they act together to enhance the immune response to gp120 and gp140 glycoproteins.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants AI41715 (to D.W.M.), AI42599 (to C.C.B.), and HL62120 (to D.W.M.) and by the Pine Family Foundation Award.

We thank Victor H. Van Cleave for his generous contribution of recombinant murine IL-12 and Bernard Arulanandam and Roberta Raeder for their technical supervision and advice. We thank the NIH AIDS Reagents Program for HIV-1 strain 89.6 (from Ronald Collman) and 2G12 antibody (from Hermann Katinger). For challenging scientific discussions and technical assistance, we thank Joyce Lynch and Victor Huber.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alfsen, A., P. Iniguez, E. Bouguyon, and M. Bomsel. 2001. Secretory IgA specific for a conserved epitope on gp41 envelope glycoprotein inhibits epithelial transcytosis of HIV-1. J. Immunol. 166:6257-6265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arulanandam, B. P., M. O'Toole, and D. W. Metzger. 1999. Intranasal interleukin-12 is a powerful adjuvant for protective mucosal immunity. J. Infect. Dis. 180:940-949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arulanandam, B. P., R. H. Raeder, J. G. Nedrud, D. J. Bucher, J. Le, and D. W. Metzger. 2001. IgA immunodeficiency leads to inadequate Th cell priming and increased susceptibility to influenza virus infection. J. Immunol. 166:226-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barackman, J. D., G. Ott, and D. T. O'Hagan. 1999. Intranasal immunization of mice with influenza vaccine in combination with the adjuvant LT-R72 induces potent mucosal and serum immunity which is stronger than that with traditional intramuscular immunization. Infect. Immun. 67:4276-4279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barre-Sinoussi, F., J.-C. Chermann, F. Rey, M. T. Nugeyre, S. Chamaret, J. Gruest, C. Dauguet, C. Axler-Blin, F. Brun-Vezinet, C. Rouzioux, W. Rozenbaum, and L. Montagnier. 1983. Isolation of a T-lymphotropic retrovirus from a patient at risk for acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Science 220:868-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belyakov, I. M., J. D. Ahlers, B. Y. Brandwein, P. Earl, B. L. Lelsall, B. Moss, W. Strober, and J. A. Berzofsky. 1998. The importance of local mucosal HIV-specific CD8(+) cytotoxic T lymphocytes for resistance to mucosal viral transmission in mice and enhancement of resistance by local administration of IL-12. J. Clin. Investig. 102:2072-2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bessen, D., and V. A. Fischetti. 1988. Passive acquired mucosal immunity to group A streptococci by secretory immunoglobulin A. J. Exp. Med. 167:1945-1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyer, J. D., A. D. Cohen, K. E. Ugen, R. L. Edgeworth, M. Bennett, A. Shah, K. Schumann, B. Nath, A. Javadian, M. L. Bagarazzi, J. Kim, and D. B. Weiner. 2000. Therapeutic immunization of HIV-infected chimpanzees using HIV-1 plasmid antigens and interleukin-12 expressing plasmids. AIDS 14:1515-1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradney, C. P., G. D. Sempowski, H. X. Liao, B. F. Haynes, and H. F. Staats. 2002. Cytokines as adjuvants for the induction of anti-human immunodeficiency virus peptide immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgA antibodies in serum and mucosal secretions after nasal immunization. J. Virol. 76:517-524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coutelier, J. P., G. Warnier, and Van J. Snick. 1987. IgG2a restriction of murine antibodies elicited by viral infections. J. Exp. Med. 165:64-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devito, C., J. Hinkula, R. Kaul, L. Lopalco, J. J. Bwayo, F. Plummer, M. Clerici, and K. Broliden. 2000. Mucosal and plasma IgA from HIV-exposed seronegative individuals neutralize a primary HIV-1 isolate. AIDS 14:1917-1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devito, C., K. Broliden, R. Kaul, L. Svensson, K. Johansen, P. Kiama, J. Kimani, L. Lopalco, S. Piconi, J. J. Bwayo, F. Plummer, M. Clerici, and J. Hinkula. 2000. Mucosal and plasma IgA from HIV-1-exposed uninfected individuals inhibit HIV-1 transcytosis across human epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 165:5170-5176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Earl, P. L., C. C. Broder, D. Long, S. A. Lee, J. Peterson, S. Chakrabarti, R. W. Doms, and B. Moss. 1994. Native oligomeric human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein elicits diverse monoclonal antibody reactivities. J. Virol. 68:3015-3026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Earl, P. L., W. Sugiura, D. C. Montefiori, C. C. Broder, S. A. Lee, C. Wild, J. Lifson, and B. Moss. 2001. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of oligomeric human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp140. J. Virol. 75:645-653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gallichan, W. S., and K. L. Rosenthal. 1996. Effects of the estrous cycle on local humoral immune responses and protection of intranasally immunized female mice against herpes simplex virus type 2 infection in the genital tract. Virology 224:487-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerhard, W., K. Mozdzanowska, M. Furchner, G. Washko, and K. Maiese. 1997. Role of the B-cell response in recovery of mice from primary influenza virus infection. Immunol. Rev. 159:95-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gherardi, M. M., J. C. Ramirez, and M. Esteban. 2000. Interleukin-12 (IL-12) enhancement of the cellular immune response against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Env antigen in a DNA prime/vaccinia virus boost vaccine regimen is time and dose dependent: suppressive effects of IL-12 boost are mediated by nitric oxide. J. Virol. 74:6278-6286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamajima, K., Y. Hoshino, K. Q. Xin, F. Hayashi, K. Tadokoro, and K. Okuda. 2002. Systemic and mucosal immune responses in mice after rectal and vaginal immunization with HIV-DNA vaccine. Clin. Immunol. 102:8-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horner, A. A., S. K. Datta, K. Takabayashi, I. M. Belyakov, T. Hayashi, N. Cinman, M.-D. Nguyen, J. H. Van Uden, J. A. Berzofsky, D. D. Richman, and E. Raz. 2001. Immunostimulatory DNA-based vaccines elicit multifaceted immune responses against HIV at systemic and mucosal sites. J. Immunol. 167:1584-1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huber, V. C., B. P. Arulanandam, P. M. Arnaboldi, M. K. Elmore, C. E. Sheehan, B. V. S. Kallakury, and D. W. Metzger. Delivery of IL-12 intranasally leads to reduced IL-12-mediated toxicity. Int. Immunopharmacol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Igarashi, T., C. Brown, A. Azadegan, N. Haigwood, D. Dimitrov, M. A. Martin, and R. Shibata. 1999. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 neutralizing antibodies accelerate clearance of cell-free virions from blood plasma. Nat. Med. 5:211-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johansson, E. L., C. Rask, M. Fredriksson, K. Eriksson, C. Czerkinsky, and J. Holmgren. 1998. Antibodies and antibody-secreting cells in the female genital tract after vaginal or intranasal immunization with cholera toxin B subunit or conjugates. Infect. Immun. 66:514-520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaul, R., D. Trabattoni, J. J. Bwayo, D. Arienti, A. Zagliani, F. M. Mwangi, C. Kariuki, E. N. Ngugi, K. S. MacDonald, T. B. Ball, M. Clerici, and F. A. Plummer. 1999. HIV-1-specific mucosal IgA in a cohort of HIV-1-resistant Kenyan sex workers. AIDS 13:23-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim, J. J., V. Ayyavoo, M. l. Bagarazzi, M. A. Chattergoon, K. Dang, B. Wang, J. D. Boyer, and D. B. Weiner. 1997. In vivo engineering of a cellular immune response by coadministration of IL-12 expression vector with a DNA immunogen. J. Immunol. 158:816-826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liao, H. X., B. Etemad-Moghadam, D. C. Montefiori, Y. Sun, J. Sodroski, R. M. Scearce, R. W. Doms, J. R. Thomasch, S. Robinson, N. L. Letvin, and B. F. Haynes. 2000. Induction of antibodies in guinea pigs and rhesus monkeys against the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope: neutralization of nonpathogenic and pathogenic primary isolate simian/human immunodeficiency virus strains. J. Virol. 74:254-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lowell, G. H., R. W. Kaminski, T. C. VanCott, B. Slike, K. Kersey, E. Zawoznik, L. Loomis-Price, G. Smith, R. R. Redfield, S. Amselem, and D. L. Birx. 1997. Proteosomes, emulsomes, and cholera toxin B improve nasal immunogenicity of human immunodeficiency virus gp160 in mice: induction of serum, intestinal, vaginal, and lung IgA and IgG. J. Infect. Dis. 175:292-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mascola, J. R., G. Stiegler, T. C. VanCott, H. Katinger, C. B. Carpenter, C. E. Hanson, H. Beary, D. Hayes, S. S. Frankel, D. L. Birx, and M. G. Lewis. 2000. Protection of macaques against vaginal transmission of a pathogenic HIV-1/SIV chimeric virus by passive infusion of neutralizing antibodies. Nat. Med. 6:207-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mazzoli, S., D. Trabattoni, S. Lo Caputo, S. Piconi, C. Ble, F. Meacci, S. Ruzzante, A. Salvi, F. Semplici, R. Longhi, M. L. Fusi, N. Tofani, M. Biasin, M. L.Villa, F. Mazzotta, and M. Clerici. 1997. HIV-specific mucosal and cellular immunity in HIV-seronegative partners of HIV-seropositive individuals. Nat. Med. 3:1250-1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mazzoli, S., L. Lopalco, A. Salvi, D. Trabattoni, S. Lo Caputo, F. Semplici, M. Biasin, C. Ble, A. Cosma, C. Pastori, F. Meacci, F. Mazzotta, M. L. Villa, A. G. Siccardi, and M. Clerici. 1999. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-specific IgA and HIV neutralizing activity in the serum of exposed seronegative partners of HIV-seropositive persons. J. Infect. Dis. 180:871-875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moja, P., C. Tranchat, I. Tchou, B. Pozzetto, F. Lucht, C. Desgranges, and C. Genin. 2000. Neutralization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) mediated by parotid IgA of HIV-1-infected patients. J. Infect. Dis. 181:1607-1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Montefiori, D. C., B. S. Graham, J. Zhou, J. Zhou, R. A. Bucco, D. H. Schwartz, L. A. Cavacini, M. R. Posner, et al. 1993. V3-specific neutralizing antibodies in sera from HIV-1 gp160-immunized volunteers block virus fusion and act synergistically with human monoclonal antibody to the conformation-dependent CD4 binding site of gp120. J. Clin. Investig. 92:840-847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moog, C., C. Spenlehauer, H. Fleury, F. Heshmati, S. Saragosti, F. Letourneur, A. Kirn, and A. M. Aubertin. 1997. Neutralization of primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates: a study of parameters implicated in neutralization in vitro. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 13:19-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Motzer, R. J., A. Rakhit, L. H. Schwartz, T. Olencki, T. M. Malone, K. Sandstrom, et al. 1998. Phase I trial of subcutaneous recombinant human interleukin-12 in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 4:1183-1191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moulard, M., S. K. Phogat, Y. Shu, A. F. Labrijin, X. Xiao, J. M. Binley, M.-Y. Zhang, I. A. Sidorov, C. C. Broder, J. Robinson, P. W. H. I. Parren, D. R. Burton, and D. S. Dimitrov. 2002. Broadly cross-reactive HIV-1-neutralizing human monoclonal Fab selected for binding to gp120-CD4-CCR5 complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:6913-6918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Overbergh, L., D. Valckx, M. Waer, and M. Chantal. 1999. Quantification of murine cytokine mRNAs using real time quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR. Cytokine 11:305-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parr, M. B., G. R. Harrimann, and E. L. Parr. 1998. Immunity to vaginal HSV-2 infection in immunoglobulin A knockout mice. Immunology 95:208-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prabhala, R. H., and C. R. Wira. 1991. Cytokine regulation of the mucosal immune system: in vivo stimulation by IFN-γ of secretory component and immunoglobulin A in uterine secretions and proliferation of lymphocytes from spleen. Endocrinology 129:2915-2923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reiner, S. L., S. Zheng, D. B. Corry, and R. M. Locksley. 1993. Constructing polycompetitor cDNAs for quantitative PCR. J. Immunol. Methods 165:37-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sollid, L. M., D. Kvale, P. Brandzaeg, G. Markussen, and E. Thornsby. 1987. Interferon-γ enhances expression of secretory component, the epithelial receptor for polymeric immunoglobulins. J. Immunol. 138:4303-4306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Staats, H. F., S. P. Montgomery, and T. J. Palker. 1997. Intranasal immunization is superior to vaginal, gastric, or rectal immunization for the induction of systemic and mucosal anti-HIV antibody responses. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 13:945-952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tamura, S.-I., H. Funato, Y. Hirabayashi, K. Kikuta, and Y. Suzuki. 1990. Functional role of respiratory tract haemagglutinin-specific IgA antibodies in protection against influenza. Vaccine 8:479-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.VanCott, T., R. W. Kaminski, J. R. Mascola, V. S. Kalyanaraman, N. M. Wassef, C. R. Alving, J. T. Ulrich, G. H. Lowell, and D. L. Birx. 1998. HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies in the genital and respiratory tracts of mice intranasally immunized with oligomeric gp160. J. Immunol. 160:2000-2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van der Meide, P. H., F. Villinger, A. A. Ansari, R. J. Groenestein, M. C. D. C. de Labie, Y. J. M. van der Hout, W. H. Koornstra, W. M. J. M. Bogers, and J. L. Heeney. 2002. Stimulation of both humoral and cellular immune responses to HIV-1 gp120 by interleukin-12 in Rhesus macaques. Vaccine 20:2296-2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Voss, G., and F. Villinger. 2000. Adjuvanted vaccine strategies and live vector approaches for the prevention of AIDS. AIDS 14(Suppl. 3):S153-S165. [PubMed]

- 45.Wassef, N. M., and S. F. Plaeger. 2002. Cytokines as adjuvants for HIV DNA vaccines. Clin. Appl. Immunol. Rev. 2:229-240. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilson, J. A., M. Hevey, and M. K. Hart. 2000. Epitopes involved in antibody-mediated protection from Ebola virus. Science 287:1664-1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu, H.-Y., S. Abdu, D. Stinson, and M. W. Russell. 2000. Generation of female genital tract antibody responses by local or central (common) mucosal immunization. Infect. Immun. 68:5539-5545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu, H.-.Y, and M. W. Russell. 1998. Induction of mucosal and systemic immune responses by intranasal immunization using recombinant cholera toxin B subunit as an adjuvant. Vaccine 16:286-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu, H.-.Y, H. Nguyen, and M. W. Russell. 1997. Nasal lymphoid tissue (NALT) as a mucosal inductive site. Scand. J. Immunol. 46:506-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]