Abstract

To evaluate human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) replication and selection of drug-resistant viruses during seemingly effective highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), multiple HIV-1 env and pol sequences were analyzed and viral DNA levels were quantified from nucleoside analog-experienced children prior to and during a median of 5.1 (range, 1.8 to 6.4) years of HAART. Viral replication was detected at different rates, with apparently increasing sensitivity: 1 of 10 by phylogenetic analysis; 2 of 10 by viral evolution with increasing genetic distances from the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) of infection; 3 of 10 by selection of drug-resistant mutants; and 6 of 10 by maintenance of genetic distances from the MRCA. When four- or five-drug antiretroviral regimens were given to these children, persistent plasma viral rebound did not occur despite the accumulation of highly drug-resistant genotypes. Among the four children without genetic evidence of viral replication, a statistically significant decrease in the genetic distance to the MRCA was detected in three, indicating the persistence of a greater number of early compared to recent viruses, and their HIV-1 DNA decreased by ≥0.9 log10, resulting in lower absolute DNA levels (P = 0.007). This study demonstrates the variable rates of viral replication when HAART has suppressed plasma HIV-1 RNA for years to a median of <50 copies/ml and that combinations of four or five antiretroviral drugs suppress viral replication even after short-term virologic failure of three-drug HAART and despite ongoing accumulation of drug-resistant mutants. Furthermore, the decrease of cellular HIV-1 DNA to low absolute levels in those without genetic evidence of viral replication suggests that monitoring viral DNA during HAART may gauge low-level replication.

Administration of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has been associated with improved immunologic function and survival in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-infected individuals (22, 35). However, only 40 to 65% of subjects have continued suppression of HIV-1 replication to below the limits of detection after 6 months or more of treatment (22, 29, 38, 50, 51, 59). While partial suppression of viral replication offers immunologic benefits (6), the duration of these benefits may be limited to several years (7). Multiple factors have been associated with foreshortening the antiviral activity of HAART, including the selection of drug-resistant mutants (12, 26, 39, 41, 49). Among individuals in whom HAART appears effective, as defined by plasma HIV-1 levels consistently below the limit of detection of currently licensed assays (50 copies of RNA/ml of plasma), viral replication nevertheless may persist at low levels (5, 11, 16, 19, 21, 25, 32, 36, 43, 48, 61, 63). The extent and effects of low-level replication on the efficacy of HAART have not been fully characterized.

To gain insight into the emergence of drug resistant HIV-1 during apparently effective therapy, the viral population in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of children was characterized when plasma HIV-1 RNA levels were below the limit of detection over a median of 5.1 years of HAART. Of particular interest were whether the evolution of resistant virus could be detected within PBMC prior to a rebound of plasma HIV-1 RNA to detectable levels, whether mutations accumulated over time with the eventual loss of suppression of viral replication, and whether simple identifiers were associated with low-level viral replication during apparently effective HAART.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design.

Children with plasma HIV-1 RNA levels of <50 copies/ml after 1 to 2 years of HAART were enrolled into the study, with consent obtained from each child's guardian by one of the investigators in accordance with Institutional Review Board guidelines. Plasma HIV-1 RNA copy numbers were determined every 1 to 6 months by using bDNA (Chiron Corp, Emeryville, Calif.), Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor 1.0 (Roche Diagnostics, Montclair, N.J.), or Ultra Sensitive Monitor 1.0 (Roche) assays, with lower limits of detection of 500, 400, and 50 copies/ml, respectively. Lymphocyte subsets were determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis (34). Adherence to prescribed HAART was evaluated by a formal questionnaire or parental report of the number of doses missed during the most recent 2 days and during the entire time interval preceding each monthly clinic visit. Multiple HIV-1 pol and env sequences were obtained from endpoint dilutions of enrollees' PBMC collected prior to HAART and every 6 to 12 months during 1.8 to 6.5 years of effective HAART and, when viremia was detected, from endpoint dilutions of plasma.

Sampling of HIV-1 populations by limiting dilution PCR of PBMC DNA and quantification of DNA copy number in CD4+ cells.

DNA for PCR was obtained from a known quantity of PBMC by lysis with a detergent-proteinase K solution (62) or by extraction using the IsoQuick nucleic acid extraction kit (Orca Research Inc, Bothell, Wash.). HIV-1 DNA was quantified by endpoint-dilution PCR (44). The viral DNA load per 106 CD4+ cells was then calculated. Specimens were diluted so that no more than 30% of the reactions were positive after nested PCR, providing 70 to 80% probability that a positive reaction was from a single viral template.

Nucleic acids encoding protease (PR), reverse transcriptase (RT), and the C2-V5 region of Env were coamplified in first-round PCRs using either two or three outer primer sets in the same reaction. The PR- and RT-encoding regions were amplified either individually, with PRL (5′-GGGACCAGCGGCTACACTAGAAGAAATGATGACAGCATGTCAGG-3′) and PR2 (5′-GGAGTATTGTATGGATTTTCAGGCC-3′) plus RT1 and RT2 (18), or amplified as one fragment with PRL and RT2. In either case, env was simultaneously amplified using ED31 and BH2 (17). Second-round PCRs were conducted separately, using pro primers PRC (5′-CTCCCCCTCAGAAGCAGGAGCCGATAGACAAGGAACTGTATCC-3′) and PR4 (5′-GGGCCATCCATTCCTGGC-3′), rt primers RT4 and RT3 (18) (or pol primers PRC and RT3), and env primers ES7 and ES8 (9). Samples that did not amplify with the forward PR primers PRL and PRC were amplified using either pol-forward outer and pol-forward inner (19), PRF1 (5′-GAGCCAAGTAACAAATTCAGC-3′) and PRF2 (5′-CACCAGAAGAGAGCTTCAGGT-3′), or PRA (5′-CCTAGGAAAAAGGGCTGTTGGAAATGTGG-3′) and PRB (5′-ACTGAGAGACAGGCTAATTTTTTAGGGA-3′). PCR and direct DNA sequencing of PCR products were performed as previously described (45). The resulting sequences with evidence of polymorphic residues, thus indicating the presence of multiple templates, were excluded from our analyses.

Sequence analysis.

Sequences were assembled and error checked using Sequencher 3.0 (Gene Codes, Ann Arbor, Mich.). Those with substantial G→A mutational bias (as determined using HYPERMUT [28]), suggesting hypermutation (24, 57), were omitted from further analyses. Sequence alignments were obtained using ClustalW 1.7 (55) and manually edited as necessary. Regions of ambiguous alignment were removed from subsequent evolutionary analyses. Neighbor-joining phylogenetic trees of each subject's Env, PR, and RT coding sequences were constructed using PAUP* version 4.0b4 (54) with evolutionary models selected using the Akaike information criterion (1) under Modeltest 3.0 (42). Consequently, most env trees used the general time-reversible model with gamma-distributed heterogeneity of substitution rates (31). Model parameters are available from the authors upon request. Phylogenetic trees of the nucleotide sequences encoding HIV-1 Env, PR, and RT from each patient were constructed separately and rooted using HIV-1 sequences from his or her mother, when available, or several closely related HIV-1 sequences from GenBank. The reliability of clustering in phylograms was assessed by bootstrapping analyses (15). More complete information related to the phylogenetic analyses of virus from all subjects can be found at the website http://ubik.microbiol.washington.edu/HIV/Frenkel-2/index.html.

The most recent common ancestor (MRCA) sequence of a given infection was inferred as the sequence at the node that included all of the sequences for a given gene region (PR, RT, or env C2-V5) for a given patient. This sequence was obtained using maximum likelihood estimation using PAUP*, and the divergence rates from the MRCA were calculated using linear regression over time (30).

Statistical analyses.

Logistic regression analysis was applied to the prevalence of genetic mutants over time, with tests to determine whether the coefficient for time was significantly different from zero. When analysis was conducted on more than one individual, generalized estimating equations were used to account for the correlations resulting from repeated measures from the same individual (10). The log10-transformed HIV-1 DNA levels before and during potent HAART were compared using Student's two-tailed t test.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank accession numbers of the HIV-1 pol and env sequences derived in this study are AY075701 to AY077450.

RESULTS

Patient population, antiretroviral history, and HIV-1 RNA and DNA levels.

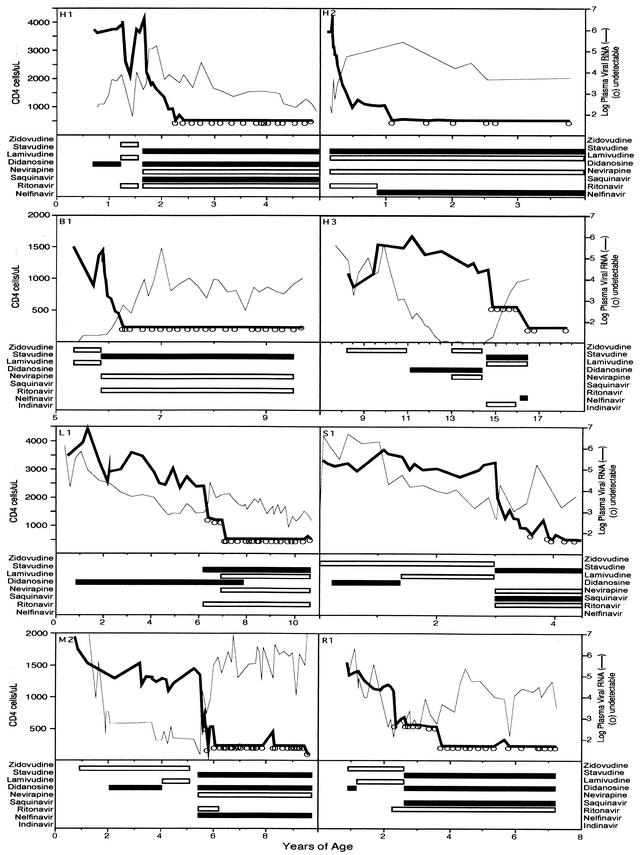

Ten children were studied before and during a median and mean of 5.1 years (range, 1.8 to 6.4 years) of protease inhibitor (PI)-containing HAART. All 10 were naïve to PI therapy when HAART was initiated; however, all had received other antiretrovirals (Fig. 1). The initial HAART regimens included three or four drugs, including one to two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI) and one to two PI, with or without one non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), except for one child (L1) who was treated with only stavudine and ritonavir as part of a clinical trial. “Potent HAART,” defined as combination therapy with three classes of drugs (NRTI, NNRTI, and PI) or with two NRTI and two PI, was prescribed to 9 of the 10 participants during the course of this study.

FIG. 1.

HIV-1 RNA and CD4+ cell levels and antiretroviral treatments for eight subjects (data for subjects G1 and G2 are provided below in Fig. 4 and 5, respectively). The plasma HIV-1 RNA and CD4+ cell levels and antiretroviral drug regimens are shown for nucleoside analog-experienced children whose viral genetics were studied during a median of 5.1 years of HAART. Plasma HIV-1 RNA rebounded in G1, G2, H1, and R1 shortly after starting HAART. All subjects except H3 were ultimately treated with potent HAART, defined as combination therapy with three classes of drugs (NRTI, NNRTI, and PI) or with two NRTI and two PI, during which the median plasma viral RNA level was <50 copies/ml.

Adherence to prescribed therapy was judged to be ≥95% (missing zero to three doses per month) in 7 of the 10 children: in G2, H3, L1, R1, and B1 from the time therapy was initiated; in G1 after resolution of pneumonia that developed during the month he began three-drug HAART; and in H1 after the placement of a gastrostomy tube prior to starting a second potent HAART regimen. H2 had ≥95% adherence except during a brief time during his fourth year of therapy. In contrast, subjects M2 and S1 reported missing one to two doses per week. In addition, M2 missed multiple doses during 1 month in her fifth year of HAART due to problems within her family.

Plasma HIV-1 RNA levels were determined a median of six times per year (range, two to nine) after falling below the limit of detection (Table 1; see also Fig. 1, 2, 4, and 5). Four children had a rebound of viral plasma RNA to >500 copies/ml during their initial two-class, three-drug HAART regimens (two NRTI plus one PI). Two of these, G2 (see Fig. 5) and R1 (see Fig. 1), reported complete adherence to HAART during this period; however, their regimens included nucleoside analogs that they had taken previously. Viral rebound in the other two was associated with difficulties in adherence, due to illness (G1 [see Fig. 4A]) and the disagreeable taste of ritonavir (H1 [see Fig. 1]). HAART potency was increased by the addition and switching of antiretroviral agents in these four and in a fifth child (L1 [see Fig. 1]) who did not have plasma viral rebound but began HAART with only two drugs. After these modifications in therapy, 9 of 10 children were receiving potent HAART. During potent HAART, plasma HIV-1 RNA levels were sustained at a median <50 copies/ml for a combined total of 40 patient years. Rebounds of >250 copies/ml occurred in only two during potent HAART, in H2 and M2, with 589 and 1,215 copies/ml, respectively, both during periods of nonadherence.

TABLE 1.

Summary of subjects' characteristics and HIV-1 evolution

| Subject | Age at start of HAART (years) | Years of HAART (dates) | Distance from MRCA during HAART (P value of distance over time compared to zero)a

|

Episodes of rebound plasma HIV-1 RNA by year of HAARTb

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Env | RT | PR | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |||

| B1 | 5.9 | 4.8 (11/97-9/02) | 0.009 | 0.800 | 0.070 | 0/7 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/5 | ||

| G1 | 9.1 | 6.4 (4/96-9/02) | 0.020 | <0.001 | 0.030 | 1/6 | 0/6 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 1/8 | 0/6 | 0/2 |

| G2 | 11.2 | 6.4 (4/96-9/02) | 0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0/4 | 3/7 | 3/6 | 3/5 | 3/7 | 0/6 | 0/2 |

| H1 | 1.7 | 3.5 (6/97-12/00) | 0.444 | 0.860 | 0.090 | 3/9 | 1/7 | 0/6 | 0/5 | |||

| H2 | 0.2 | 5.0 (9/97-9/02) | 0.290 | 0.222 | 0.385 | 0/7 | 2/5 | 0/7 | 1/5 | 0/4 | ||

| H3 | 14.7 | 3.9 (5/96-3/00) | 0.110 | 0.350 | 0.990 | 0/4 | 0/3 | 0/2 | 0/3 | |||

| L1 | 6.2 | 5.5 (2/97-9/02) | 0.040 | 0.640 | 0.120 | 0/5 | 1/4 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 1/6 | 0/3 | |

| M2 | 5.5 | 5.2 (7/97-9/02) | 0.850 | 0.129 | 0.056 | 0/9 | 1/7 | 1/7 | 0/6 | 1/9 | 0/1 | |

| R1 | 2.3 | 6.1 (8/96-9/02) | 0.055 | 0.720 | 0.490 | 2/7 | 0/6 | 0/5 | 1/5 | 0/5 | 0/4 | |

| S1 | 3.0 | 1.8 (7/97-3/99) | 0.690 | 0.440 | 0.740 | 0/9 | 1/4 | |||||

P values shown in boldface indicate increasing distance.

Number of episodes per number of measurements (per year). Values in bold indicate rebound to >500 copies/ml. Underlined values indicate that subjects were receiving only two classes of drugs; otherwise, subjects were receiving potent HAART.

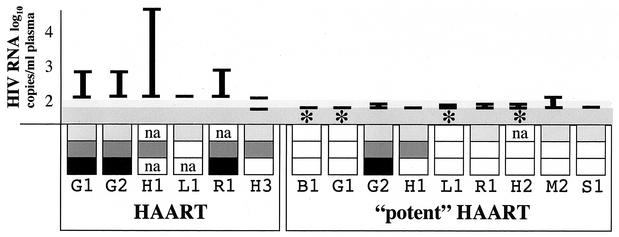

FIG. 2.

Summary of virologic studies. Subjects, identified by a letter and number, are grouped by intensity of therapy. “HAART” was treatment with NRTI and one PI, except for L1 who received a two-drug regimen of stavudine and ritonavir. “Potent HAART” was treatment with three classes of drugs, except for G1 who was prescribed two NRTI and two PI. The ranges of plasma HIV-1 RNA levels are indicated by vertical bars, as is the lower limit of detection of the assay used (shaded areas); a horizontal bar (—) indicates that all values were below the limit of detection. A decrease of ≥0.9 log10 in HIV-1 DNA in CD4+ cells within 1 to 2 years of potent HAART is indicated by an asterisk. Findings from sequence analyses are indicated in the boxes as follows: light gray, genetic distances of env from MRCA were stable or increased during HAART; dark gray, selection of new and/or increases in established HIV-1 drug-resistant mutations; black, evolution of HIV-1 in phylogram confirmed by distances from MRCA; white, decay of drug-resistant mutant prevalence or no phylogenetic evidence of viral evolution. na, not applicable due to no pre-HAART drug-resistant mutants, or not assessed. Viral replication and associated viral evolution were diminished in association with potent HAART.

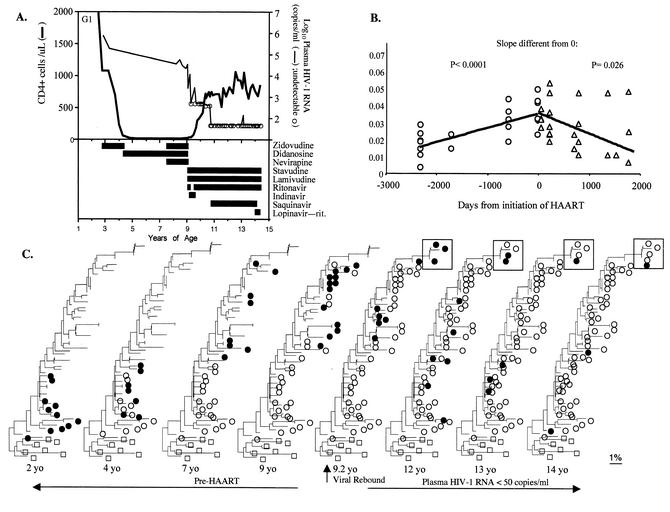

FIG. 4.

Clinical history and viral sequence analyses of a subject with regressive viral evolution during potent HAART. (A) Clinical course and laboratory values, including drug history, plasma HIV-1 RNA levels, and CD4+ and CD8+ cell numbers. (B) The genetic distances of these sequences from the inferred MRCA for pol encoding PR are shown. (C) The neighbor-joining phylogenetic analysis for HIV-1 encoding PR is shown, with multiple iterations showing the virus detected at the indicated time points as filled circles and viruses from past time points as open circles. Pre-HAART specimens demonstrated time-ordered evolution, and within 5 months of beginning three-drug HAART in 1996 a drug-resistant mutant (N88S, within box) was selected. Subsequently, and in association with the intensification of HAART, there was a gradual diminution of viral sequences that grouped with more recent time points, except for a few drug-resistant variants (N88S) that persisted but did not evolve or increase in prevalence. After 5 years of HAART, the detection of PBMC sequences that grouped with those from earlier time points suggested die-off of more recently infected cells, also documented by the decrease in distance from the MRCA.

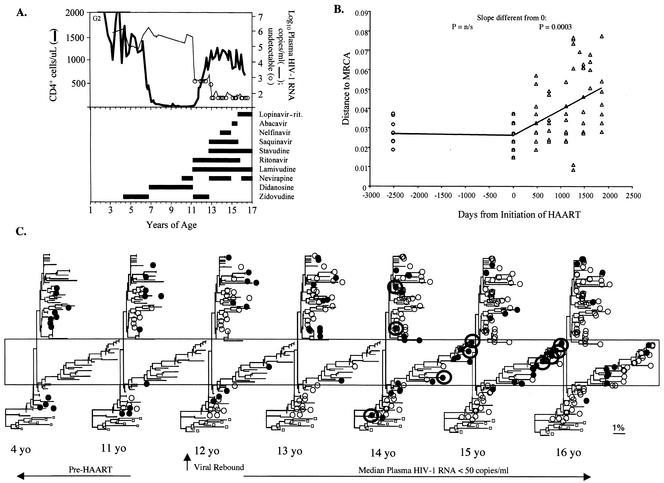

FIG. 5.

Clinical history and viral sequence analyses of a subject with evidence for significant viral replication and forward viral evolution during HAART with a median viral load of <50 copies/ml. (A) Clinical course and laboratory values, including drug history, plasma HIV-1 RNA levels, and CD4+ and CD8+ cell numbers. (B) Genetic distances of HIV-1 RNA sequences from the inferred MRCA for pol encoding PR. (C) Neighbor-joining phylogenetic analysis for HIV-1 encoding PR, with multiple iterations showing the virus detected at the indicated time points as filled circles and viruses from past time points as open circles. Three months after initiating HAART, when no plasma HIV-1 RNA was detected, mutations associated with resistance to ritonavir and other protease inhibitors were detected in PBMC. Viral rebound to 1,200 copies/ml occurred after 6 months of HAART. The regimen was intensified, after which the median plasma viral load was <50 copies/ml; however, during 3.8 years of potent HAART this patient had 9 plasma HIV-1 RNA determinations between 50 and 101 copies/ml, and on 10 occasions the patient had <50 copies/ml. Plasma viral variants (circled) grouped with PBMC-derived viral DNA from early in the course of infection (near the root of the 14-year-old tree, at left) and with highly mutated PBMC virus (in box) that included variants with new drug resistance mutations to all three classes of antiretrovirals. Low-level viremia ceased, and the HIV-1 DNA in CD4+ cells decreased by >1 log10 when lopinavir-ritonavir was substituted for ritonavir and saquinavir.

PBMC viral DNA load decreased in four children by ≥0.9 log10 between 1 and 2 years of potent HAART (Table 2). The pre-HAART viral DNA load in these four children was similar (P = 0.731) to that in those who had a <0.9 log10 decrease; however, their post-HAART loads were significantly lower (P = 0.007; Student's t test).

TABLE 2.

Marked decline and low absolute HIV-1 DNA load after 1 to 2 years of HAART in subjects without genetic evidence for viral replicationa

| Subject | Viral divergence during HAART | Log10 HIV-1 DNA copies/ 106 CD4+ cells

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-HAART | Post-HAART | ||

| With <0.9 log10 decrease | |||

| H3 | Stable | 2.8 | 2.3 |

| M2 | Trend to increase | 2.6 | 2.6 |

| R1 | Stable | 3.5 | 2.9 |

| S1 | Stable | 3.2 | 2.9 |

| G2 | Increased | 2.6 | 3.6 |

| H1 | Stable | 3.7 | 3.7 |

| Mean (95% CI)b | 3.08 (2.58, 3.57) | 2.99 (2.41, 3.58) | |

| With ≥0.9 log10 decrease | |||

| G1 | Decreased | 2.7 | 1.8 |

| L1 | Decreased | 2.8 | 1.6 |

| B1 | Decreased | 3.2 | 2.1 |

| H2 | Stable | 3.3 | 2.0 |

| Mean (95% CI) | 2.98 (2.49, 3.46) | 1.90 (1.54, 2.27) | |

| P | 0.731 | 0.007 | |

Subjects were sorted by the magnitude of HIV-1 DNA load change (<0.9 log10 or ≥0.9 log10 decrease in HIV-1 DNA copies per 106 CD4+ cells) after potent HAART (and three-drug HAART in H3). The absolute pre-HAART HIV-1 DNA log10-transformed values were similar between the two groups, while the post-HAART values were significantly lower among those with decreases of ≥0.9 log10 in HIV-1 DNA copies/106 CD4+ cells, Interestingly, the subjects with a ≥0.9 log10 decrease had less viral genetic evidence for viral replication during HAART, with either no viral diversification after starting potent HAART during primary infection (H2) or decreasing viral divergence from the MRCA of infection (see Table 1). In contrast, the viral populations of those with a <0.9 log10 or no decrease in HIV-1 DNA load maintained or increased in divergence from the MRCA during HAART (see Table 1), indicating a greater degree of viral replication. Viral replication was indeed detected in H3, G2, and H1 by selection of drug-resistant mutants (Fig. 3A) and was likely in M2, R1, and S1 due to the persistence of a genetically diverse viral population. These observations suggest that a ≥0.9 log10 decrease in HIV-1 DNA copies/106 CD4+ cells or a low absolute HIV-1 DNA level indicates profound suppression of viral replication.

CI, confidence interval.

Selection of drug resistance mutations and viral rebound related to the potency of HAART.

Despite plasma HIV-1 RNA below the limits of detection, new drug-resistant mutants or increases in the population of existing drug-resistant mutants were detected (Fig. 2 and 3). New mutants were observed in three of six children during two-class, three-drug HAART (for PR, N88S in G1 and V82A, L90M in G2 [Fig. 4C and 5C, respectively]); (for RT, M184V in G2 and H1 [data not shown]), and in one of nine during potent HAART (in G2, PR mutants L10I, I54V, A71V/T, V82F, and I84V [Fig. 5C]; RT mutants V106A, Y181C, and a hypermutated sequence with a T69SEA insertion [data not shown]).

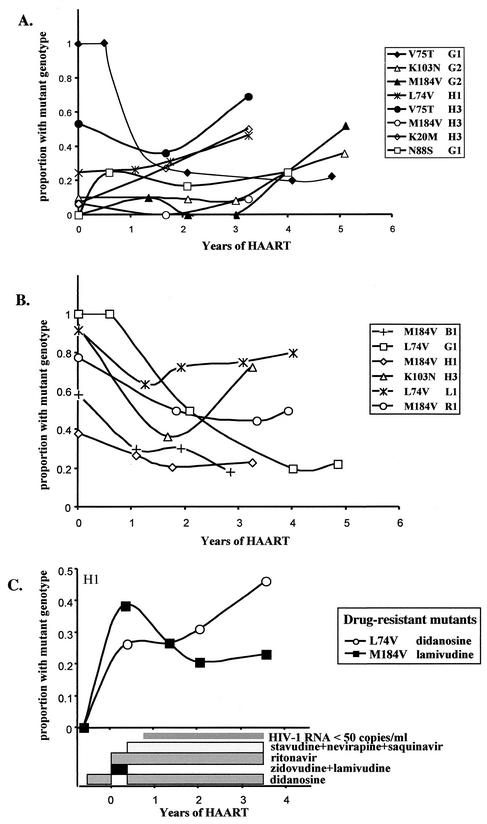

FIG. 3.

Frequency of drug-resistant mutations during HAART. The percentages of sequences with drug-resistant mutations in PBMC are shown during a median of 5.1 years of effective HAART. (A) Mutants selected by the HAART regimen increased slowly in relative frequency (P < 0.0001), indicating ongoing low-level viral replication, although plasma HIV-1 RNA levels were <50 copies/ml. (B) Over the same period of time, mutants not selected by the ongoing HAART decreased in frequency (P = 0.0013), either due to relative increases in selected viruses or to a die-off of cells with more recently selected virus and relative persistence of virus from early infection. (C) Shifts in the prevalence of mutants in subject H1 show selection of L74V during didanosine-containing HAART and diminution of M184V after cessation of lamivudine (linear regression of slope of L74V versus M184V frequencies after cessation of lamivudine, P = 0.018).

Three of the four episodes of viral rebound during nonpotent HAART were coincident with, or followed, detection of drug-resistant mutants not previously found in the subjects. The V82A and L90M in PR and M184V in RT were observed in 10% of subject G2's PBMC 3.5 months before rebound; however, no specimens were available from the months preceding rebound in the other two with novel mutants detected at viral rebound (G1 and H1). No novel mutations were associated with rebound in R1, who reported complete adherence to three-drug HAART that had been formulated by the addition of ritonavir to ongoing lamivudine and zidovudine. In addition, during potent HAART no novel mutations were detected with the isolated plasma viral rebounds associated with nonadherence to antiretrovirals by H2 and M2.

Although no sustained viral rebound was detected among subjects during potent HAART (Table 1 and Fig. 1 and 2), episodes of transient viremia were detected in subject G2 with plasma viral RNA levels between 50 and 101 copies/ml on 9 of 19 occasions during 3.8 years of three-class, five-drug HAART (Fig. 5). The prevalence of PI-resistant mutants increased in his PBMC (0% in 1996, 30% in 2000, and 55% in 2001; P = 0.0005) and in his plasma (58% in late 1999 to 100% in 2000). Notably, mutations conferring high-level resistance to all three classes of antiretrovirals predominated in his plasma and PBMC virus load (RT had T69SEA, K103N, V106A, Y181C, M184V, T215F/Y, and K219Q; PR had L10I, I54V, A71V/T, V82A/F, I84V, and L90M), yet viral rebound was not sustained. Subsequent to the substitution of lopinavir-ritonavir (Kaletra) for saquinavir and ritonavir, his plasma HIV-1 RNA was <50 copies/ml in all nine assays over 19 months and his viral DNA load decreased by >1 log10/106 CD4+ cells to 1.8 log10 copies/106 CD4+ PBMC.

Drug-resistant mutants detected in PBMC prior to the initiation of HAART generally increased in prevalence when selected for by three-drug and potent HAART regimens (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3A), although in one subject, G1, the frequency of mutants (V75T) decreased over several years of HAART. Simultaneously, mutants selected by drugs in previous but not the current regimens decreased in prevalence (P = 0.0013) (Fig. 3B). An absence of relevant drug-resistant mutants prevented the evaluation of all subjects for these trends.

Phylogenetic and genetic distance analysis.

Three viral phylogenetic patterns, forward, no, and regressive evolution, were determined by statistical analysis of genetic distances from the MRCA (Table 1). “Forward evolution” (a statistically significant increase in distance from the MRCA) occurred in G2 (Fig. 5B) and to a lesser degree in M2 (PR distance [P = 0.056]) during potent HAART (Table 1). “No evolution” was detected in H1, H2, H3, R1, and S1. Nonetheless, low levels of replication (Fig. 3A) were indicated in H1 and H3 by increases in the prevalence of certain drug-resistant mutants during potent and nonpotent HAART, respectively, and were suggested in R1 and S1 by persistence of genetic diversity during HAART (data not shown). However, there was no diversification of the viral population of H2, who began HAART during primary infection shortly after a course of peripartum zidovudine (data not shown). “Regressive evolution,” with viral sequences becoming more similar to the MRCA of infection (i.e., to early virus) during HAART compared to pre-HAART sequences, was pronounced in three subjects, B1, G1, and L1, during potent HAART (Table 1). Notably, the three subjects with regressive evolution and H2 had pronounced decreases in viral DNA load (Table 2).

Another important observation in the phylogenetic analysis was that plasma viral RNA detected intermittently at low levels (50 to 101 copies/ml in G2 [Fig. 5C] and R1 [data not shown]) included genotypes typical of those found shortly after infection, indicating that viral genomes similar to those in long-lived cells were replication competent.

DISCUSSION

Various analyses of viral gene sequences from 10 children during HAART with median plasma HIV-1 RNA levels of <50 copies/ml over a median of 5.1 years detected replication in 1 to 6 subjects of 10, depending on the method employed. Whether viral replication remained at low levels, manifest only by selection of drug-resistant mutants, or was marked and resulted in resumption of detectable plasma viremia appeared to be related to the potency of the child's HAART regimen. Children without evidence of viral replication by any method had marked decreases and low absolute levels of HIV-1 DNA per 106 CD4+ cells.

Viral replication during HAART when plasma viral RNA was below the level of detection was indicated in six children by several different analyses of viral genotypes. Phylogenetic analysis, as used in previous studies (60, 63), revealed viral replication. However, this was the least sensitive measure of replication, detecting replication in 1 of the 10 children studied. Ranking the methods utilized in this study according to increasingly more sensitive measurements of viral replication, after phylogenetic analysis, was as follows: increasing genetic distances from the MRCA; the selection of novel drug-resistant mutants; increases in the frequency of drug-resistant mutants antedating HAART; and stable genetic distances, or divergence, from the MRCA. The four children without evidence of replication by any of the aforementioned tests, including no viral diversification following primary infection or with genetic distances that approached the MRCA, were assumed to have insignificant viral replication.

HIV-1 DNA levels normalized to CD4+ PBMC appeared to be a sensitive indicator of residual viral replication in the children we studied. While HIV-1 DNA levels before HAART were similar among children that did and did not have evidence of replication during HAART, those without replication had a ≥0.9 log10 decrease in their HIV-1 DNA and significantly lower absolute HIV-1 DNA concentration in CD4+ PBMC after 1 to 2 years of HAART, compared to no change in levels among children with replication. These data suggest that HIV-1 DNA levels might be useful in gauging low-level replication among individuals with plasma HIV-1 RNA below the limits of detection. Data from others' studies similarly suggest that PBMC HIV-1 DNA loads correlate with markers of viral nucleic acid synthesis (2, 4, 20, 27, 37, 61), as have intracellular viral RNA levels (4) and the ratio of unspliced to multiply spliced HIV-1 mRNA (19). Decreases in total HIV-1 levels associated with viral replication well-suppressed by HAART appear primarily due to decreases in unintegrated HIV-1 DNA (27). HIV-1 DNA levels have also correlated closely with the level of plasma RNA, grouped as <3, 3 to 50, and 50 to 200 copies/ml (61), and a strong correlation was observed between viral DNA and intracellular viral RNA levels (P = 0.005; r = 0.69) among 18 subjects with plasma HIV-1 RNA levels of <200 copies/ml, including 15 with <20 copies/ml (4). In contrast to our study, these data correlating HIV-1 RNA and DNA levels do not prove that full cycles of viral replication with infection of new cells were ongoing. Viral particles and mRNA can be derived from provirus without resulting in the infection of additional cells. Thus, it would follow that individuals with higher levels of provirus would produce more viral RNA. Our study, by demonstrating increases in the proportion of viral DNA with drug resistance mutations, indicates full cycles of viral replication were ongoing, with HAART failing to completely suppress the infection of additional cells.

Genetic bottlenecks affecting viral replication capacity (8, 33; T. Wrin, A. Gamarnik, N. Whitehurst, J. Beauchaine, J. M. Whitcomb, N. S. Hellman, and C. J. Petropoulos, abstract from the 5th International Workshop on HIV Drug Resistance and Treatment Strategies 2001, Antivir. Ther. 6:20, 2001) and pharmacologic barriers (12, 40) imposed by HAART appeared critical to limiting viral replication among the children we studied. These effects were demonstrated by the suppression of viral replication by potent four- or five-drug HAART after virologic failure of three-drug regimens. The selection of increasingly drug-resistant but implicitly poorly fit viruses in one subject during nearly 4 years of potent HAART demonstrated that the genetic barrier posed by a therapeutic regimen could persist for a sustained period of time. The importance of pharmacologic barriers was observed in this same subject when episodes of transient viremias ceased following the substitution of lopinavir-ritonavir for saquinavir and ritonavir in his five-drug regimen. Furthermore, strengthening of the pharmacologic barrier by lopinavir-ritonavir was associated with a decrease in HIV-1 DNA in his CD4+ cells to an absolute level in the range of those in the children without viral genetic evidence of replication. While we suspect that the replication capacity of his drug-resistant mutants was impaired, this was not assessed in vitro (52; Wrin et al., Antivir. Ther. 6:20, 2001), and thus we did not estimate the relative contribution of the genetic and pharmacokinetic barriers of his HAART on the suppression of viral replication.

In the one case evaluated, new drug-resistant mutants were detected in PBMC DNA prior to rebound of plasma viral RNA. This finding suggests that monitoring virus in PBMC by sensitive assays (3, 13, 47, 53, 56, 58) may have clinical utility in forecasting viral rebound.

Among our subjects with 5 to 6 years of profound suppression of viral replication, the persisting PBMC viral genotypes were similar to virus detected early in the course of HIV-1 infection. The abundance of early genotypes in the persisting viral population most likely results from a relatively greater number of long-lived cells becoming infected during the period of acute infection compared to similar time intervals during later stages of disease. The persisting early viral population appeared to include replication-competent virus, since HIV-1 genotypes typical of early infection were detected in the plasma of two children we studied and by others studying latent cellular and low-level virus in the blood (23, 46). Importantly, PBMC containing drug-resistant mutants, while decreasing in relative frequency during HAART, persisted at low levels in all individuals for years following the cessation of the selecting drug, as others have observed (23, 46). The relative loss of more recently infected PBMC and the persistence of virus from early infection may explain why plasma viremia during effective HAART is often genetically similar to archival virus (23) and why the viral phenotype has been observed to revert from X4/syncytium- to R5/non-syncytium-inducing virus during HAART (14). However, immune reconstitution and return to a more healthful cytokine milieu could also limit the replication of X4/syncytium-inducing viruses.

In summary, analysis of viral population genetics over a median of 5.1 years of effective HAART detected ongoing replication in a significant subset of children, with the most sensitive indicators being a selection of new or an increasing frequency of preexisting drug-resistant mutants in PBMC and maintenance of the mean genetic distance from the MRCA of infection. Among children with ongoing selection of drug-resistant mutants documented, viral rebound appeared to be limited by potent four- and five-drug HAART regimens, presumably by selection of viruses with impaired replication capacity. Furthermore, subjects without genetic evidence of viral replication had a greater persistence of viral genotypes typical of early infection compared to recently evolved viral sequences. In addition, their HIV-1 DNA levels decreased markedly with HAART and to lower absolute levels compared to subjects with ongoing viral replication, providing a rationale for studies evaluating whether HIV-1 DNA levels predict subsequent virologic failure among subjects with plasma HIV-1 RNA levels of <50 copies/ml.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grants, the University of Washington Center for AIDS Research, and the Foster Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akaike, H. 1974. A new look at statistical model identification. IEEE Trans. Autom. Contr. 19:716-723. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andreoni, M., L. Sarmati, L. Ercoli, E. Nicastri, G. Giannini, C. Galluzzo, M. F. Pirillo, and S. Vella. 1997. Correlation between changes in plasma HIV RNA levels and in plasma infectivity in response to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 13:555-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beck, I. A., M. Mahalanabis, G. Pepper, A. Wright, S. Hamilton, E. Langston, and L. M. Frenkel. 2002. A rapid and sensitive oligonucleotide ligation assay for the detection of mutations in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 associated with high-level resistance to protease inhibitors. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1413-1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burgard, M., J. Izopet, B. Dumon, C. Tamalet, D. Descamps, A. Ruffault, A. Vabret, G. Bargues, M. Mouroux, I. Pellegrin, S. Ivanoff, O. Guisthau, V. Calvez, J. M. Seigneurin, and C. Rouzioux. 2000. HIV RNA and HIV DNA in peripheral blood mononuclear cells are consistent markers for estimating viral load in patients undergoing long-term potent treatment. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 16:1939-1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chun, T. W., L. Stuyver, S. B. Mizell, L. A. Ehler, J. A. Mican, M. Baseler, A. L. Lloyd, M. A. Nowak, and A. S. Fauci. 1997. Presence of an inducible HIV-1 latent reservoir during highly active antiretroviral therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:13193-13197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deeks, S. G. 2001. Durable HIV treatment benefit despite low-level viremia: reassessing definitions of success or failure. JAMA 286:224-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deeks, S. G., J. D. Barbour, R. M. Grant, and J. N. Martin. 2002. Duration and predictors of CD4 T-cell gains in patients who continue combination therapy despite detectable plasma viremia. AIDS 16:201-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deeks, S. G., T. Wrin, T. Liegler, R. Hoh, M. Hayden, J. D. Barbour, N. S. Hellman, C. J. Petropoulos, J. M. McCune, M. Hellerstein, and R. M. Grant. 2001. Virologic and immunologic consequences of discontinuing combination antiretroviral drug therapy in HIV-infected patients with detectable viremia. N. Engl. J. Med. 344:472-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delwart, E. L., E. G. Shpaer, F. E. McCutchan, J. Louwagie, M. Grez, H. Rübsamen-Waigmann, and J. I. Mullins. 1993. Genetic relationships determined by a DNA heteroduplex mobility assay: analysis of HIV-1 env genes. Science 262:1257-1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diggle, P. J., K. Y. Liang, and S. L. Zeger. 1994. Analysis of longitudinal data. Clarendon Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 11.Dornadula, G., H. Zhang, B. VanUitert, J. Stern, L. Livornese, Jr., M. J. Ingerman, J. Witek, R. J. Kedanis, J. Natkin, J. DeSimone, and R. J. Pomerantz. 1999. Residual HIV-1 RNA in blood plasma of patients taking suppressive highly active antiretroviral therapy. JAMA 282:1627-1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Durant, J., P. Clevenbergh, R. Garraffo, P. Halfon, S. Icard, P. Del Giudice, N. Montagne, J. M. Schapiro, and P. Dellamonica. 2000. Importance of protease inhibitor plasma levels in HIV-infected patients treated with genotypic-guided therapy: pharmacological data from the Viradapt Study. AIDS 14:1333-1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edelstein, R. E., D. A. Nickerson, V. O. Tobe, L. A. Manns-Arcuino, and L. M. Frenkel. 1998. Oligonucleotide ligation assay for detecting mutations in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 pol gene that are associated with resistance to zidovudine, didanosine, and lamivudine. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:569-572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Equils, O., E. Garratty, L. S. Wei, S. Plaeger, M. Tapia, J. Deville, P. Krogstad, M. S. Sim, K. Nielsen, and Y. J. Bryson. 2000. Recovery of replication-competent virus from CD4 T cell reservoirs and change in coreceptor use in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected children responding to highly active antiretroviral therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 182:751-757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felsenstein, J. 1985. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39:783-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finzi, D., M. Hermankova, T. Pierson, L. M. Carruth, C. Buck, R. E. Chaisson, T. C. Quinn, K. Chadwick, J. Margolick, R. Brookmeyer, J. Gallant, M. Markowitz, D. D. Ho, D. D. Richman, and R. F. Siliciano. 1997. Identification of a reservoir for HIV-1 in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Science 278:1295-1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frenkel, L. M., J. I. Mullins, G. H. Learn, L. Manns-Arcuino, B. L. Herring, M. L. Kalish, R. W. Steketee, D. M. Thea, J. E. Nichols, S.-L. Liu, A. Harmache, X. He, D. Muthui, A. Madan, L. Hood, A. T. Haase, M. Zupancic, K. Staskus, S. M. Wolinsky, P. Krogstad, J. Zhao, I. Chen, R. Koup, D. D. Ho, B. T. Korber, R. J. Apple, R. W. Coombs, S. Pahwa, and N. J. J. Roberts. 1998. Genetic evaluation of suspected cases of transient HIV-1 infection of infants. Science 280:1073-1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frenkel, L. M., L. E. Wagner II, S. M. Atwood, T. J. Cummins, and S. Dewhurst. 1995. Specific, sensitive, and rapid assay for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 pol mutations associated with resistance to zidovudine and didanosine. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:342-347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furtado, M. R., D. S. Callaway, J. P. Phair, K. J. Kunstman, J. L. Stanton, C. A. Macken, A. S. Perelson, and S. M. Wolinsky. 1999. Persistence of HIV-1 transcription in peripheral-blood mononuclear cells in patients receiving potent antiretroviral therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 340:1614-1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garrigue, I., I. Pellegrin, B. Hoen, B. Dumon, M. Harzic, M. H. Schrive, D. Sereni, and H. Fleury. 2000. Cell-associated HIV-1-DNA quantitation after highly active antiretroviral therapy-treated primary infection in patients with persistently undetectable plasma HIV-1 RNA. AIDS 14:2851-2855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gunthard, H. F., S. D. Frost, A. J. Leigh-Brown, C. C. Ignacio, K. Kee, A. S. Perelson, C. A. Spina, D. V. Havlir, M. Hezareh, D. J. Looney, D. D. Richman, and J. K. Wong. 1999. Evolution of envelope sequences of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in cellular reservoirs in the setting of potent antiviral therapy. J. Virol. 73:9404-9412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hammer, S. M., K. E. Squires, M. D. Hughes, J. M. Grimes, L. M. Demeter, J. S. Currier, J. J. Eron, Jr., J. E. Feinberg, H. H. Balfour, Jr., L. R. Deyton, J. A. Chodakewitz, and M. A. Fischl. 1997. A controlled trial of two nucleoside analogues plus indinavir in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection and CD4 cell counts of 200 per cubic millimeter or less. N. Engl. J. Med. 337:725-733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hermankova, M., S. C. Ray, C. Ruff, M. Powell-Davis, R. Ingersoll, R. T. D'Aquila, T. C. Quinn, J. D. Siliciano, R. F. Siliciano, and D. Persaud. 2001. HIV-1 drug resistance profiles in children and adults with viral load of <50 copies/ml receiving combination therapy. JAMA 286:196-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirsch, V. M. 1987. Structure of the simian immunodeficiency virus and its relationship to human immunodeficiency viruses. Ph.D. dissertation. Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

- 25.Hockett, R. D., J. M. Kilby, C. A. Derdeyn, M. S. Saag, M. Sillers, K. Squires, S. Chiz, M. A. Nowak, G. M. Shaw, and R. P. Bucy. 1999. Constant mean viral copy number per infected cell in tissues regardless of high, low, or undetectable plasma HIV RNA. J. Exp. Med. 189:1545-1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hogg, R. S., B. Yip, K. J. Chan, E. Wood, K. J. Craib, M. V. O'Shaughnessy, and J. S. Montaner. 2001. Rates of disease progression by baseline CD4 cell count and viral load after initiating triple-drug therapy. JAMA 286:2568-2577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Izopet, J., M. Cazabat, C. Pasquier, K. Sandres-Saune, E. Bonnet, B. Marchou, P. Massip, and J. Puel. 2002. Evolution of total and integrated HIV-1 DNA and change in DNA sequences in patients with sustained plasma virus suppression. Virology 302:393-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Korber, B. T., and P. Rose. 1999. HYPERMUT. Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, N.Mex.

- 29.Krogstad, P., S. Lee, G. Johnson, K. Stanley, J. McNamara, J. Moye, J. B. Jackson, R. Aguayo, A. Dieudonne, M. Khoury, H. Mendez, S. Nachman, and A. Wiznia. 2002. Nucleoside-analogue reverse-transcriptase inhibitors plus nevirapine, nelfinavir, or ritonavir for pretreated children infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34:991-1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Learn, G. H., D. Muthui, S. J. Brodie, T. Zhu, K. Diem, J. I. Mullins, and L. Corey. 2002. Virus population homogenization following acute human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 76:11953-11959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leitner, T., S. Kumar, and J. Albert. 1997. Tempo and mode of nucleotide substitutions in gag and env gene fragments in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 populations with a known transmission history. J. Virol. 71:4761-4770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martinez-Picado, J., M. P. DePasquale, N. Kartsonis, G. J. Hanna, J. Wong, D. Finzi, E. Rosenberg, H. F. Gunthard, L. Sutton, A. Savara, C. J. Petropoulos, N. Hellmann, B. D. Walker, D. D. Richman, R. Siliciano, and R. T. D'Aquila. 2000. Antiretroviral resistance during successful therapy of HIV type 1 infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:10948-10953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martinez-Picado, J., A. V. Savara, L. Sutton, and R. T. D'Aquila. 1999. Replicative fitness of protease inhibitor-resistant mutants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 73:3744-3752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Melvin, A. J., K. M. Mohan, L. A. Arcuino, R. E. Edelstein, and L. M. Frenkel. 1997. Clinical, virologic and immunologic responses of children with advanced human immunodeficiency virus type 1 disease treated with protease inhibitors. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 16:968-974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Montaner, J. S., P. Reiss, D. Cooper, S. Vella, M. Harris, B. Conway, M. A. Wainberg, D. Smith, P. Robinson, D. Hall, M. Myers, and J. M. Lange. 1998. A randomized, double-blind trial comparing combinations of nevirapine, didanosine, and zidovudine for HIV-infected patients: the INCAS trial, Italy, The Netherlands, Canada and Australia Study. JAMA 279:930-937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Natarajan, V., M. Bosche, J. A. Metcalf, D. J. Ward, H. C. Lane, and J. A. Kovacs. 1999. HIV-1 replication in patients with undetectable plasma virus receiving HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy. Lancet 353:119-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ngo-Giang-Huong, N., C. Deveau, I. Da Silva, I. Pellegrin, A. Venet, M. Harzic, M. Sinet, J. F. Delfraissy, L. Meyer, C. Goujard, and C. Rouzioux. 2001. Proviral HIV-1 DNA in subjects followed since primary HIV-1 infection who suppress plasma viral load after one year of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 15:665-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paediatric European Network for Treatment of AIDS. 2002. Comparison of dual nucleoside-analogue reverse-transcriptase inhibitor regimens with and without nelfinavir in children with HIV-1 who have not previously been treated: the PENTA 5 randomised trial. Lancet 359:733-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paterson, D. L., S. Swindells, J. Mohr, M. Brester, E. N. Vergis, C. Squier, M. M. Wagener, and N. Singh. 2000. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann. Intern. Med. 133:21-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perno, C. F., F. M. Newcomb, D. A. Davis, S. Aquaro, R. W. Humphrey, R. Calio, and R. Yarchoan. 1998. Relative potency of protease inhibitors in monocytes/macrophages acutely and chronically infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J. Infect. Dis. 178:413-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Phillips, A. N., S. Staszewski, R. Weber, O. Kirk, P. Francioli, V. Miller, P. Vernazza, J. D. Lundgren, and B. Ledergerber. 2001. HIV viral load response to antiretroviral therapy according to the baseline CD4 cell count and viral load. JAMA 286:2560-2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Posada, D., and K. A. Crandall. 1998. MODELTEST: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics 14:817-818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramratnam, B., J. E. Mittler, L. Zhang, D. Boden, A. Hurley, F. Fang, C. A. Macken, A. S. Perelson, M. Markowitz, and D. D. Ho. 2000. The decay of the latent reservoir of replication-competent HIV-1 is inversely correlated with the extent of residual viral replication during prolonged anti-retroviral therapy. Nat. Med. 6:82-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rodrigo, A. G., P. C. Goracke, K. Rowhanian, and J. I. Mullins. 1997. Quantitation of target molecules from polymerase chain reaction-based limiting dilution assays. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 13:737-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rodrigo, A. G., E. W. Hanley, P. C. Goracke, and G. H. Learn. 2001. Sampling and processing HIV molecular sequences: a computational evolutionary biologist's perspective, p. 1-17. In A. G. Rodrigo and G. H. Learn (ed.), Computational and evolutionary analyses of HIV sequences. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston, Mass.

- 46.Ruff, C. T., S. C. Ray, P. Kwon, R. Zinn, A. Pendleton, N. Hutton, R. Ashworth, S. Gange, T. C. Quinn, R. F. Siliciano, and D. Persaud. 2002. Persistence of wild-type virus and lack of temporal structure in the latent reservoir for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in pediatric patients with extensive antiretroviral exposure. J. Virol. 76:9481-9492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schmit, J. C., L. Ruiz, L. Stuyver, K. Van Laethem, I. Vanderlinden, T. Puig, R. Rossau, J. Desmyter, E. De Clerg, B. Clotet, and A. M. Vandamme. 1998. Comparison of the LiPA HIV-1 RT test, selective PCR and direct solid phase sequencing for the detection of HIV-1 drug resistance mutations. J. Virol. Methods 73:77-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sharkey, M. E., I. Teo, T. Greenough, N. Sharova, K. Luzuriaga, J. L. Sullivan, R. P. Bucy, L. G. Kostrikis, A. Haase, C. Veryard, R. E. Davaro, S. H. Cheeseman, J. S. Daly, C. Bova, R. T. Ellison III, B. Mady, K. K. Lai, G. Moyle, M. Nelson, B. Gazzard, S. Shaunak, and M. Stevenson. 2000. Persistence of episomal HIV-1 infection intermediates in patients on highly active anti-retroviral therapy. Nat. Med. 6:76-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Skowron, G., J. C. Street, and E. M. Obee. 2001. Baseline CD4+ cell count, not viral load, correlates with virologic suppression induced by potent antiretroviral therapy. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 28:313-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Starr, S. E., C. V. Fletcher, S. A. Spector, F. H. Yong, T. Fenton, R. C. Brundage, D. Manion, N. Ruiz, M. Gersten, M. Becker, J. McNamara, L. M. Mofenson, L. Purdue, S. Siminski, B. Graham, D. M. Kornhauser, W. Fiske, C. Vincent, H. W. Lischner, W. M. Dankner, and P. M. Flynn. 1999. Combination therapy with efavirenz, nelfinavir, and nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors in children infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. N. Engl. J. Med. 341:1874-1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Staszewski, S., J. Morales-Ramirez, K. T. Tashima, A. Rachlis, D. Skiest, J. Stanford, R. Stryker, P. Johnson, D. F. Labriola, D. Farina, D. J. Manion, and N. M. Ruizm. 1999. Efavirenz plus zidovudine and lamivudine, efavirenz plus indinavir, and indinavir plus zidovudine and lamivudine in the treatment of HIV-1 infection in adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 341:1865-1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stoddart, C. A., T. J. Liegler, F. Mammano, V. D. Linquist-Stepps, M. S. Hayden, S. G. Deeks, R. M. Grant, F. Clavel, and J. M. McCune. 2001. Impaired replication of protease inhibitor-resistant HIV-1 in human thymus. Nat. Med. 7:712-718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stuyver, L., A. Wyseur, A. Rombout, J. Louwagie, T. Scarcez, C. Verhofstede, D. Rimland, R. Schinazi, and R. Rossau. 1997. Line probe assay for rapid detection of drug-selected mutations in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase gene. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:284-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Swofford, D. L. 1999. PAUP 4.0: phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (and other methods), ed. 4.0b2a. Sinauer Associates, Inc., Sunderland, Mass.

- 55.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Van Laethem, K., K. Van Vaerenbergh, J.-C. Schmit, S. Sprecher, P. Hermans, V. De Vroey, R. Schuurman, T. Harrer, M. Witvrouw, E. Van Wijngaerden, L. Stuyver, M. Van Ranst, J. Desmyter, E. De Clercq, and A.-M. Vandamme. 1999. Phenotypic assays and sequencing are less sensitive than point mutation assays for detection of resistance in mixed HIV-1 genotypic populations. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 22:107-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vartanian, J.-P., A. Meyerhans, B. Asjö, and S. Wain-Hobson. 1991. Selection, recombination, and G→A hypermutation of human immunodeficiency virus type I genome. J. Virol. 65:1779-1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Villahermosa, M. L., I. Beck, L. Pérez-Álvarez, G. Contreras, L. M. Frenkel, S. Osmanov, E. Vazquez de Parga, E. Delgado, N. Manjón, M. T. Cuevas, M. M. Thomson, L. Medrano, and R. Nájera. 2001. Detection and quantification of multiple drug resistance-associated mutation in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase by an oligonucleotide ligation assay. J. Hum. Virol. 4:238-248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wiznia, A., K. Stanley, P. Krogstad, G. Johnson, S. Lee, J. McNamara, J. Moye, J. B. Jackson, H. Mendez, R. Aguayo, A. Dieudonne, A. Kovacs, M. Bamji, E. Abrams, S. Rana, J. Sever, and S. Nachman. 2000. Combination nucleoside analog reverse transcriptase inhibitor(s) plus nevirapine, nelfinavir, or ritonavir in stable antiretroviral therapy-experienced HIV-infected children: week 24 results of a randomized controlled trial. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 16:1113-1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wong, J. K., M. Hezareh, H. F. Günthard, D. V. Havlir, C. C. Ignacio, C. A. Spina, and D. D. Richman. 1997. Recovery of replication-competent HIV despite prolonged suppression of plasma viremia. Science 278:1291-1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yerly, S., T. V. Perneger, S. Vora, B. Hirschel, and L. Perrin. 2000. Decay of cell-associated HIV-1 DNA correlates with residual replication in patients treated during acute HIV-1 infection. AIDS 14:2805-2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zack, J. A., A. M. Haislip, P. Krogstad, and I. S. Chen. 1992. Incompletely reverse-transcribed human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomes in quiescent cells can function as intermediates in the retroviral life cycle. J. Virol. 66:1717-1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang, L., B. Ramratnam, K. Tenner-Racz, Y. He, M. Vesanen, S. Lewin, A. Talal, P. Racz, A. S. Perelson, B. T. Korber, M. Markowitz, and D. D. Ho. 1999. Quantifying residual HIV-1 replication in patients receiving combination antiretroviral therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 340:1605-1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]