Abstract

Objective: To describe knowledge, attitudes, and awareness of bipolar disorder detection, ascertainment, and treatment among primary care physicians in a managed care setting.

Method: Quota sampling was used to obtain 102 completed surveys assessing knowledge, attitudes, and awareness of bipolar disorder from a pool of 350 primary care physicians in a large, vertically integrated Midwestern health system from June 2004 through August 2004. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the distribution of the study results at the physician level.

Results: Primary care physicians are experiencing challenges in diagnosing and treating bipolar patients, who can be difficult and time-consuming. In answering questions about major depressive episode and manic episode symptoms, at least 15% of respondents assessed most symptoms incorrectly. In analyzing 3 case studies, 9%, 11%, and 28% of respondents, respectively, answered all of the questions correctly. When asked which drugs are U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved for the maintenance treatment of adults with bipolar I disorder, no survey respondent replied correctly for all drugs listed. Importantly, our survey also indicates that these physicians are very willing to refer bipolar patients to psychiatrists for evaluation and treatment, which may help to ensure optimal care.

Conclusions: Opportunities for improvement exist in diagnosing and treating patients with bipolar disorder in the primary care setting, perhaps aided by guidelines, education, and a collaborative care model with psychiatry.

Bipolar disorder afflicts approximately 1% of the general population, with 1-year U.S. community-based prevalence ranging from 1.2% in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study1 to 1.3% in the National Comorbidity Survey.2 In a review of 10 lifetime prevalence studies of bipolar I disorder from 1985 to 1994, Angst3 observed a range of 0.0% to 0.7%. In this same review, a range of 0.2% to 3.0% for bipolar II prevalence was found in 9 studies conducted from 1978 to 1998.3

Importantly, there is an emerging “spectrum” of the disorder, described by Hirschfeld4 and others, suggesting that subclinical symptoms may play a larger role and encompass a larger population than previously believed.5,6 Judd and Akiskal7 have shown that inclusion of subclinical cases would increase the prevalence of bipolar disorder as much as 5-fold.

The literature contains evidence that bipolar disorder is an underdiagnosed condition. In a recent clinical series, 37% to 40% of patients in one center with a hospital discharge diagnosis of bipolar disorder had been considered to have unipolar depression prior to admission.8,9 A primary care practice-based study reported that, of those who screened positive for bipolar disorder, 72.3% sought professional help for their symptoms, but only 8.4% reported receiving a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.10 Among those patients screening positive for bipolar disorder, only 6.5% reported taking a mood-stabilizing agent in the past month. Further, in this study primary care physicians recorded evidence of current depression in 49.0% of those screening positive for bipolar disorder, but did not record a bipolar disorder diagnosis either in administrative billing or in the medical record of any of these patients.10 Similarly, a recent clinic-based study conducted among patients taking an antidepressant for depression found that almost two thirds of those screening positive for bipolar disorder had never received that diagnosis.11

These findings are important because the decision to prescribe activating antidepressants, including some of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, may exaggerate manic symptoms associated with bipolar disorder and lead to adverse outcomes, including rapid cycling and increased refractoriness to treatment.12–15 Typically, rapid cycling is a post hoc diagnosis. Retrospective analysis by Perugi and colleagues16 has shown that rapid cycling (in addition to suicide and psychotic symptoms) is more likely to occur in those whose bipolar illness includes depression as the episode at onset than in those with manic or mixed-state onset. This finding has led to a link between antidepressant medication use and the induction of rapid cycling because of the higher rates of antidepressant use in those with depressive onset.

The lifetime risk of suicide in bipolar disorder is among the highest for any mental or physical condition. This risk was estimated to be 18.9% in a meta-analysis of 29 studies prior to 1988,14 with mortality rates in the untreated bipolar population approaching those of heart disease and cancer.

Because of the prevalence of bipolar disorder in the general population, the difficulty in distinguishing bipolar from other disorders, and the high suicide rate, it is extremely important to determine the extent to which primary care physicians have an understanding of the condition, its diagnosis, and its current treatment options. The present study seeks to evaluate the general level of knowledge and ability of primary care physicians in a managed care setting to identify and diagnose bipolar disorder. Additionally, this research assesses awareness of appropriate treatment of patients with bipolar disorder among primary care physicians, along with the attitudes of these physicians toward the recognition and treatment of bipolar patients and any associated barriers to therapy.

METHOD

Study Site

We conducted this study in a large, vertically integrated health system serving the primary and specialty health care needs of Midwestern residents. This system is affiliated with a multispecialty salaried physician group that provides most of the care for health system patients; approximately 350 of these doctors practice in primary care. These physicians are similar to private-practice physicians in that they have few constraints related to providing care to their patients. The health system owns a large, nonprofit, mixed-model health maintenance organization (HMO). In order to optimize the data available for this study, the population was limited to medical group physicians who provide patient care for HMO members. The institutional review board reviewed and approved of the study and the content of the surveys.

Physician Questionnaire

There is no standardized instrument available for assessing physician knowledge, attitudes, and awareness concerning bipolar disorder; therefore, we developed our own. We used a quota sampling approach and distributed surveys to primary care sites on a rolling basis with a goal of 100 completed surveys from primary care physicians. Included in the survey were questions capturing physician demographics, knowledge of bipolar disorder symptoms, therapeutic options for bipolar disorder, and attitudes toward patients with bipolar disorder. Also included were 3 clinical vignettes developed by one of the study authors (a psychiatrist [C.F.]) in an effort to obtain more realistic insight into diagnostic approaches and acumen.

In an effort to remove any ambiguity in the knowledge questions about signs and symptoms of disease, we used the DSM-IV17 criteria exclusively and worded questions and response categories to directly and transparently reflect this approach.

Data Analysis

We calculated descriptive statistics to characterize the distribution of study results at the physician level. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, N.C.). Descriptive statistics were used as appropriate to describe the distributions of responses.

RESULTS

We received 102 completed surveys from the primary care physicians. The mean age of surveyed primary care physicians was 42 years, and the mean number of years practiced in their specialty was 12. Forty-four of the respondents were male, and 58 were female. Eighty of the responding physicians worked in internal medicine, while 22 were in family practice. The majority (80%) of respondents were attending physicians, while 18% identified themselves as residents (with 2% choosing “other”).

Knowledge and Awareness

Diagnostic knowledge

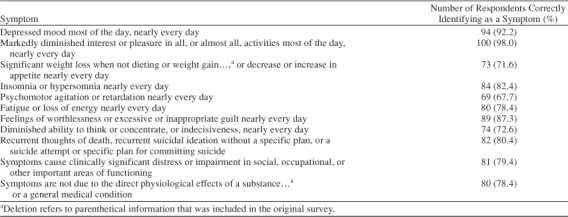

The initial knowledge questions required the respondent to select critical component DSM-IV defining disorder symptoms from a checklist. Table 1 presents the results of this question for major depressive episode. While almost all primary care physicians correctly identified depressed mood, diminished interest in activities, and feelings of worthlessness, the remaining symptoms were not correctly identified by up to one third of this group.

Table 1.

Identification of Defining Symptoms of a Major Depressive Episode (DSM-IV) by Primary Care Physicians (N = 102)

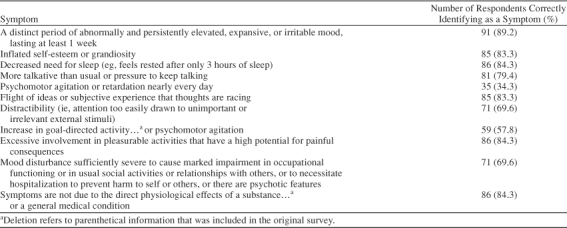

Respondents were asked to identify the defining symptoms of a manic episode according to DSM-IV (Table 2). Eighty-nine percent of respondents correctly identified a distinct period of abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood lasting at least 1 week as a manic-episode symptom. However, at least 15% of respondents (and as many as two thirds) assessed the other symptoms incorrectly.

Table 2.

Identification of Defining Symptoms of a Manic Episode (DSM-IV) by Primary Care Physicians (N = 102)

This trend continued when physicians were asked to identify characteristics of bipolar I disorder according to DSM-IV. Almost 20% of respondents did not know that bipolar I disorder patients may have a history of 1 or more major depressive episodes, and 51% did not know that bipolar I disorder can be subclassified as a first-time or recurrent experience. Forty-seven percent of primary care physician respondents correctly identified the symptoms of rapid cycling (at least 4 episodes of a mood disturbance in a 12-month period), while almost 22% incorrectly believed that rapid cycling is rapid alteration in the same 24-hour period between mania and depression, and almost 30% reported that they did not know the answer to the question.

A series of questions about distinguishing between major depression and bipolar depression indicated that one third (33%) of respondents were aware that the defining symptoms of major depression and bipolar depression are the same. Similarly, approximately 34% of the physicians correctly identified all of the factors helpful in distinguishing major depression from bipolar depression.

In an effort to assess whether physicians linked impairment with symptoms, a series of questions about the perceived disability associated with depression and mania symptoms was included. Almost 63% of primary care physicians surveyed felt that mania and depression are equally disabling, while almost 28% selected depression as more disabling, and almost 10% felt that mania was more disabling. In response to being asked whether, if peer-reviewed evidence were available that showed one of the symptom clusters to be more disabling, it would increase the likelihood that the respondent would screen for it, 81% of this group said yes.

Three case studies were included in the survey to provide insight into clinical application: just under 9% of respondents gave all the correct answers in the first case, 11% in the second case, and just over 28% in the third.

Treatment knowledge

While almost 43% of surveyed primary care physicians knew that antidepressants can cause cycle acceleration in bipolar disorder, almost half did not know this. When asked about weight gain associated with antipsychotic therapy, 47% correctly identified all of the factors in this phenomenon; almost 16% replied incorrectly that weight gain was not associated with this therapy.

Recommended treatment strategies for the use of anti-depressants for bipolar disorder were not clearly understood, as 22% of those who responded to this question did not know the correct answer and 17 individuals (17% of those surveyed) did not answer the question. Forty-three percent of those answering the treatment-strategy question stated correctly that long-term antidepressant therapy is not recommended for all patients with bipolar disorder. No respondents replied correctly for all drugs that are U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved for the maintenance treatment of adults with bipolar I disorder from a list, and almost 21% selected “don't know” as their answer.

Importantly, when key results were stratified for analysis by primary care specialty type (internal medicine vs. family practice), family practice trained physicians scored better than internists on this survey two thirds of the time, and on 2 questions these results achieved statistical significance (p = .02 and p = .005).

Practice and Attitudes

The practice and attitudes questions captured information about differences in attitudes toward patients with depression, mania, and bipolar disorder. Thirty-seven percent of the primary care physicians reported being comfortable managing patients with major depression; about half (53%) considered these patients more difficult to manage than other patients, and 31% felt less confident in their skills in managing these patients; 1 in 7 (14%) considered patients with major depression unrewarding to manage. This is evident, as almost 1 in 4 (23%) reported that they quickly refer their patients with major depression to a psychiatrist. Approximately 56% of these primary care physicians try initial pharmacotherapy and refer these patients to a psychiatrist if that is unsuccessful. Twenty percent of these doctors end up referring 50% of their patients with major depression to psychiatrists, and 20% end up referring 99% of their major depression patients to psychiatrists. The symptoms or features in patients with major depression that most often trigger these physicians to refer them to psychiatry are, in descending order, suicidality, symptoms resistant to treatment with antidepressants, and manic symptoms.

Recognition and treatment of bipolar disorder appears to be fairly uncommon in primary care. Almost 26% of the primary care physicians surveyed reported treating none of their patients for bipolar disorder in a year (alone or in consultation with a psychiatrist), 12% of these physicians reported treating 1 of their patients for bipolar disorder in a year, 10% reported treating 2 patients, almost 18% reported treating 5 patients, and 10% reported treating 10 patients for bipolar disorder in a year.

Half of these physicians reported that they are more likely to quickly refer to psychiatrists those patients suspected of having bipolar disorder than those with depression that doesn't respond to treatment. Sixty-four percent of these doctors stated that they always recommend psychotherapy/behavioral therapy in addition to medical treatment.

In describing criteria used to diagnose bipolar disorder, almost 72% of these physicians reported referring any patients they suspect of having bipolar disorder directly to psychiatry (and not making the diagnosis themselves). Just over 43% reported using the presence of manic symptoms in an otherwise depressed patient to evaluate for bipolar disorder, and only 1 in 4 primary care physicians reported applying formal DSM-IV criteria in evaluating their patients.

Similar to attitudes reflected in questions about major depression, responding physicians conveyed a general level of frustration in dealing with patients with bipolar disorder, as most consider these bipolar patients to be more difficult (60%) and time-consuming (51%) than other patients, or they just feel less confident in their skills to manage these patients (75%). Two thirds of physicians reported that they quickly refer their patients with bipolar disorder to a psychiatrist; approximately 33% of the physicians said that they do not like to manage any aspect of these patients' medication use because of the complexity of these therapies. A very small minority of primary care physicians (6%) reported that they attempt initial pharmacotherapy and, if unsuccessful, will immediately refer these patients to a psychiatrist, while over half of respondents (57%) refer these patients to psychiatry for evaluation and treatment.

Seventy-three percent of these primary care physicians stated that they do not see a patient at all over the course of an acute manic episode for mania-related issues, 9% stated that they see such a patient 2 to 3 times a month, and 12% reported less frequently than 1 time per month. Forty-seven percent of these primary care physicians stated that they do not see a patient at all over the course of a bipolar depression episode for depression-related issues, 17% stated that they see such a patient 2 to 3 times a month, 19% reported 1 time per month, and 15% reported less frequently than 1 time per month.

The barriers to identifying patients with bipolar disorder earlier in the course of their illness were captured in a series of questions that showed that over half (52%) of those surveyed indicated that the difficulty in detecting manic symptoms in a clinical interview is a major barrier to identifying bipolar disorder, while 46% stated that they do not have experience in recognizing bipolar disorder symptoms. Almost all (94%) of these physicians said that if there were a brief, easy to use screening instrument for bipolar disorder, they would be predisposed to use it; 41% of these primary care physicians said that they do not screen any of their patients presenting with major depression for bipolar disorder.

The primary care physicians in this study felt that some of the delays in seeking care that have been reported in the literature are due to a number of factors: 77% of these physicians suggested that patients with bipolar disorder wait before reporting symptoms because they do not consider them impairing, while 73% of these physicians cited stigma associated with mental illness as a reason for patients' waiting to report symptoms. Almost 36% of respondents thought patients with bipolar disorder who present with major depression wait 1 to 6 months before reporting symptoms or seeking help, while almost 28% thought these patients wait 6 months to a year.

DISCUSSION

Our data show that primary care physicians are experiencing challenges in diagnosing and treating patients with bipolar disorder, who can be difficult and time-consuming. In answering questions about major depressive episode and manic episode symptoms, a substantial minority of respondents assessed the majority of symptoms incorrectly. In analyzing 3 case studies on the survey, 9%, 11%, and 28% of respondents, respectively, answered all of the questions correctly. When asked a question about which drugs are FDA-approved for the maintenance treatment of adults with bipolar I disorder, no survey respondent replied correctly for all drugs listed. It is vital to understand these apparent gaps in primary care physician knowledge about bipolar disorder and current therapies, so that diagnosis, treatment, and referral can be optimized. Importantly, our survey indicates that these physicians are very willing to refer patients with bipolar disorder to psychiatrists for evaluation and treatment, which can be an important step in optimizing their care.

The results of the present study help to illuminate earlier findings. In a 2000 survey of members of the National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association (NDMDA),18 over one third of respondents with bipolar disorder were found to have sought professional help within 1 year of the onset of symptoms; however, 69% were misdiagnosed, most frequently with unipolar depression. Patients who were misdiagnosed consulted a mean of 4 physicians prior to receiving the correct diagnosis; one third waited 10 years or more before receiving an accurate diagnosis. Despite having underreported manic symptoms, more than 50% of patients believed that their physicians' lack of understanding of bipolar disorder prevented a correct diagnosis from being made earlier.19

These potential delays in diagnosis result in indirect costs as well as actual costs to the health care system. Birnbaum and colleagues,19 in their analysis of a cohort of patients treated with antidepressants, found that patients with unrecognized bipolar disorder incurred significantly higher mean monthly medical costs in the 12 months following initiation of antidepressant treatment when compared to patients with recognized bipolar disorder ($1179 vs. $801) and non-bipolar patients treated with antidepressants ($585). Monthly indirect costs from these employer data were also higher in the unrecognized bipolar disorder ($570 vs. $514 in recognized bipolar patients, $335 in non-bipolar patients treated with antidepressants).19

Our other recent study20 examined treatment patterns of antidepressants and health care utilization prior to and after an index bipolar diagnosis, and several related issues emerged. First, using our definition and assumptions, these results showed that, while one third of patients with bipolar disorder were identified rapidly (within 6 months of their initial mental health encounter), another third (31%) went for at least 4 years from their initial mental health encounter until their initial bipolar diagnosis. This suggests either that some physicians are better than others in recognizing patients with bipolar disorder or that some patients are far more difficult to diagnose. In either case, assuming that bipolar disorder was present at the initial presentation with depressive symptoms, these data indicate that barriers still exist in physicians' ability to identify bipolar disorder in the general patient population setting and to distinguish it from unipolar depression, findings that are supported by the current survey results.

We deployed a general survey to characterize some of the potential issues facing primary care physicians in the diagnosis and treatment of bipolar disorder patients. Our results can be used to identify opportunities for improving detection and treatment of bipolar disorder, target physician education efforts,21 and develop benefit-risk management programs for bipolar therapies. Typically, family physicians receive mandatory training in psychiatry and behavioral medicine while internists do not. Some of the findings of our survey may be attributed to the fact that almost 80% of the physicians in our sample were internists.

There are several potential limitations to the use and interpretation of our study results. The selection of the Henry Ford Health System as the site for our study may limit the generalizability of these findings to other physician populations. There may also be inherent limitations with the survey approach if physicians have difficulty accurately recalling or reporting aspects of their interactions with patients with bipolar disorder.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings suggest that opportunities for improvement exist for primary care physicians in terms of diagnosing and treating patients with bipolar disorder. Keeping in mind the ever-increasing time and other pressures facing primary care physicians in daily practice, the development of guidelines and other tools to help with this task will be enormously valuable. Collaboration between psychiatrists and primary care physicians in this process will be very important. The findings of this study provide useful information for designing effective educational programs and other interventions for the improved management of patients with bipolar disorder across the spectrum of clinical care.

Footnotes

This study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline.

Dr. Stang is a consultant to and has served on the speaker or advisory boards for GlaxoSmithKline and other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Burch is an employee of GlaxoSmithKline. The other authors report no additional financial or other relationships relevant to the subject matter of this article.

REFERENCES

- Regier DA, Narrow WE, and Rae DS. et al. The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system: Epidemiologic Catchment Area prospective 1 year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993 50:85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, and Zhao S. et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSMIII-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994 51:8–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angst J. The emerging epidemiology of hypomania and bipolar II disorder. J Affect Disord. 1998;50:143–151. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00142-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld RM. Bipolar spectrum disorder: improving its recognition and diagnosis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001 62suppl 14. 5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning JS, Haykal RF, and Connor PD. et al. On the nature of depressive and anxious states in a family practice setting: the high prevalence of bipolar II and related disorders in a cohort followed longitudinally. Compr Psychiatry. 1997 38:102–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC, Fechner-Bates S, Schwenk TL. Prevalence, nature, and comorbidity of depressive disorders in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1994;16:267–276. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd LL, Akiskal HS. The prevalence and disability of bipolar spectrum disorders in the US population: a re-analysis of the ECA database taking into account subthreshold cases. J Affect Disord. 2003;73:123–131. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaemi SN, Sachs GS, and Chiou AM. et al. Is bipolar disorder still underdiagnosed? are antidepressants overutilized? J Affect Disord. 1999 52:135–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaemi SN, Boiman EE, Goodwin FK. Diagnosing bipolar disorder and the effect of antidepressants: a naturalistic study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:804–808. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v61n1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das AK, Olfson M, and Gameroff MJ. et al. Screening for bipolar disorder in a primary care practice. JAMA. 2005 293:956–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld RMA, Cass AR, and Holt DCL. et al. Screening for bipolar disorder in patients treated for depression in a family medicine clinic. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005 18:233–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukopulos A, Reginaldi D, and Laddomada P. et al. Course of the manic depressive cycle and changes caused by treatments. Pharmakopsychiatr Neuropsychopharmakol. 1980 13:156–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altshuler LL, Post RM, and Leverich GS. et al. Antidepressant-induced mania and cycle acceleration: a controversy revisited. Am J Psychiatry. 1995 152:1130–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic Depressive Illness. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 1990 [Google Scholar]

- Wehr TA, Goodwin FK. Can antidepressants cause mania and worsen the course of affective illness? Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:1403–1411. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.11.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perugi C, Micheli C, and Akiskal HS. et al. Polarity of the first episode, clinical characteristics, and course of manic-depressive illness: a systematic retrospective investigation of 320 bipolar I patients. Compr Psychiatry. 2000 41:13–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld RM, Lewis L, Vornik LA. Perceptions and impact of bipolar disorder: how far have we really come? results of the National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association 2000 survey of individuals with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:161–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum HG, Shi L, and Dial E. et al. Economic consequences of not recognizing bipolar disorder patients: a cross-sectional descriptive analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003 64:1201–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stang PE, Frank CE, and Kalsekar A. et al. The clinical history and costs associated with delayed diagnosis of bipolar disorder. MedGenMed [serial online]. 2006 8:18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning JS, Zylstra RG, Connor PD. Teaching family physicians about mood disorders: a procedure suite for behavioral medicine. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;1:18–23. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v01n0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]