Abstract

The emergence of X4 human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) variants in infected individuals is associated with poor prognosis. One of the possible causes of this emergence might be the selection of X4 variants in some specific tissue compartment. We demonstrate that the thymic microenvironment favors the replication of X4 variants by positively modulating the expression and signaling of CXCR4 in mature CD4+ CD8− CD3+ thymocytes. Here, we show that the interaction of thymic epithelial cells (TEC) with these thymocytes in culture induces an upregulation of CXCR4 expression. The cytokine secreted by TEC, interleukin-7 (IL-7), increases cell surface expression of CXCR4 and efficiently overcomes the downregulation induced by SDF-1α, also produced by TEC. IL-7 also potentiates CXCR4 signaling, leading to actin polymerization, a process necessary for virus entry. In contrast, in intermediate CD4+ CD8− CD3− thymocytes, the other subpopulation known to allow virus replication, TEC or IL-7 has little or no effect on CXCR4 expression and signaling. CCR5 is expressed at similarly low levels in the two thymocyte subpopulations, and neither its expression nor its signaling was modified by the cytokines tested. This positive regulation of CXCR4 by IL-7 in mature CD4+ thymocytes correlates with their high capacity to favor X4 virus replication compared with intermediate thymocytes or peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Indeed, we observed an enrichment of X4 viruses after replication in thymocytes initially infected with a mixture of X4 (NL4-3) and R5 (NLAD8) HIV strains and after the emergence of X4 variants from an R5 primary isolate during culture in mature thymocytes.

The chemokine receptors CXCR4 and CCR5 have been identified as the main coreceptors for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) (4). A predominance of R5 HIV-1 isolates is observed during the establishment of HIV-1 infection as well as throughout the asymptomatic period. Subsequently, in about 40% of AIDS patients, an evolution towards an enrichment of X4 viruses occurs (44), concomitant with a drastic CD4 T-cell depletion (13, 28, 43, 51, 54, 58). The mechanisms involved in the emergence of X4 variants early in children (50) and at later stages of infection in adults are poorly understood. Possibly, replication of X4 variants is enhanced in specific tissue compartments because of a more efficient usage of the CXCR4 coreceptor.

The thymus is known to be a critical site for pathogenic HIV infection in humans (20, 41, 45) and in animal models of AIDS (2, 55, 63). Thymuses from pediatric patients undergoing an accelerated disease process (8, 26, 35, 38) or from adults with AIDS (14, 48) show severe thymocyte depletion associated with a profound disorganization of the thymic epithelial network. Thymic failure may also be responsible for the fact that, among patients undergoing antiretroviral therapies for advanced disease, the CD4 cell counts often remain below normal levels despite long-term suppression of viral load (32, 62). Conversely, the levels of CD4 counts progressively increase in patients producing drug-resistant HIV strains which display low replication efficiencies in thymocytes (31, 56).

We and others have shown that thymocytes are cellular targets of HIV infection (42, 47, 61). Furthermore, we have shown that HIV-1 takes advantage of activation signals required for thymocyte differentiation for its replication in thymocytes. We demonstrated that interaction of human thymocytes with thymic epithelial cells (TEC) is required for HIV replication (47). This interaction leads to the cosecretion of two cytokines crucial for virus replication, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin-7 (IL-7), that further synergize with IL-6, IL-1, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (11, 12). However the interaction with TEC appears to be efficient only in the case of mature singly positive CD4+ CD8− CD3+ (SP CD4+) thymocytes (11). These results correlate with previous studies showing that, in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques, most of the infected thymocytes are located in the medulla (30, 63), where mature thymocytes reside. However, we showed that the intermediate CD4+ CD8− CD3− thymocytes were able to replicate the virus in the presence of TNF and IL-7 (11). Specifically, restriction of viral replication in these intermediate cells was due to the lack of TNF secretion. However, in vivo, a lack of TNF might be compensated by the TNF secreted by activated macrophages that infiltrate the thymus during infection (20, 41).

In this study, we investigated the possibility that the thymus may be a site of enrichment for X4 variants. We studied the influence of the thymic microenvironment on the level of expression and signaling of the two main coreceptors CXCR4 and CCR5 in mature SP CD4+ and intermediate thymocytes. We focused on the signals induced during TEC-thymocyte interaction and particularly on the cytokines involved in the induction of virus replication. We then correlated the efficiency of regulation of these coreceptors to the ability of each of these two thymocyte populations to favor replication of X4 versus R5 variants compared to peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents. (i) Cytokines and chemokines.

Human recombinant cytokines IL-1 and IL-6 were purchased from PeproTech, Inc. (Rocky Hill, N.J.); IL-7, TNF-α, GM-CSF, stromal cell-derived factor 1α (SDF-1α), and macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (MIP-1α) were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, Minn.).

(ii) Viruses.

HIV-1 NL4-3 and NLAD8 were produced by transfecting COS-7 cells with molecular clone pNL4-3 (1) or pNLAD8 (60). NLAD8 and NL4-3 provirus differ only in the env gene sequence conferring a CXCR4 tropism on NL4-3 and a CCR5 tropism on NLAD8. Transfections of COS-7 cells were performed with SuperFect (Qiagen S.A, Courtaboeuf, France). Cell supernatants were harvested 2 and 3 days after transfection.

Primary isolates were from HIV-1-infected individuals of Vietnamese (34) (V.CT8), Italian (49) (J2758), or Central African Republic (37) (11111D and 9614C) cohorts. They were propagated on phytohemagglutinin (PHA)-IL-2-activated PBMC. The 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) was determined by using serial dilutions of virus and calculated by the method of Kärber (27). The HIV-1 p24gag antigen concentration was determined in culture supernatants with a Coulter HIV-1 p24 antigen assay (Beckman Coulter France S.A, Villepinte, France).

Cell culture conditions. (i) Preparation and culture of thymic cell populations.

Thymus fragments were obtained during elective cardiac surgery on HIV-seronegative children (ages, 6 days to 24 months).

(a) Preparation of TEC.

TEC were obtained as previously described (47) and seeded in selective medium: McCoy 5A containing 20% fetal calf serum (FCS), 1 mM l-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES, antibiotics (Gibco BRL Life Technologies, Paisley, Scotland), 500 ng of hydrocortisone (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.)/ml, and 5 × 10−9 M cholera toxin (Interchim, Montluçon, France) prior to coculture.

(b) Preparation and culture of thymocyte subpopulations.

SP CD4+ and immature CD4−/+ CD8− CD3− (consisting of a pool of triple negative CD4− CD8− CD3− [TN] and intermediate CD4+ CD8− CD3− thymocytes) thymocyte populations were obtained by negative selection as previously described (11). The thymocytes were then cultured in McCoy 5A, 10% FCS, 1 mM l-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES, and antibiotics. Where indicated, specific cytokines were added at the initiation of the cultures and then every 3 or 4 days.

(c) TEC-thymocyte coculture.

Autologous cocultures of TEC and mature SP CD4+ or immature CD4−/+ CD8− CD3− subpopulations were performed 3 days after thymic excision. A ratio of 2 × 105 thymocytes per 104 TEC per 1 ml per well (24 wells/plate) was used in each experiment.

(ii) Preparation and culture of PBMC.

PBMC were obtained from the blood of HIV-seronegative donors by Ficoll-Hypaque gradient separation (Amersham Biosciences, Orsay, France). PBMC were then cultured in RPMI 1640 (Gibco BRL), 10% FCS, 1 mM l-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES, and antibiotics and activated for 3 days with 0.5 μg of PHA (Murex Biotech Ltd., Dartford, England)/ml and then for 2 days with 540 IU of IL-2 (Proleukin; Chiron, Suresnes, France)/ml prior to infection.

(iii) Culture of human glioma cell line U87.

U87 cell lines stably expressing CD4 or coexpressing CD4 and the chemokine receptor CXCR4 or CCR5 (15, 16) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium-glucose (4.5 g/liter)-Glutamax-sodium pyruvate (Gibco BRL) containing 10% FCS, 10 mM HEPES, and antibiotics.

Infection of PBMC or thymocytes.

Freshly isolated mature SP CD4+ or immature CD4−/+ CD8− CD3− thymocytes (107) or 5 × 106 activated PBMC were infected with HIV-1 molecular clones or primary isolates for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were then washed three times and cultured in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FCS, 1 mM l-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES, and antibiotics, with 10 ng of TNF-α/ml and 10 ng of IL-7/ml for thymocytes or 540 IU of IL-2/ml for PBMC. Culture supernatants were collected at different times postinfection and assayed for the presence of HIV-1 p24 antigen.

Characterization of viral coreceptor usage.

To analyze viral coreceptor usage, U87 cells expressing CD4 CXCR4 or CD4 CCR5 were seeded into 96-well plates at a concentration of 104 cells/well in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium-glucose (4.5 g/liter)-Glutamax-sodium pyruvate containing 10% FCS, 10 mM HEPES, and antibiotics. Twenty-four hours later, the cells were infected with serial dilutions of virus for 2 h at 37°C, washed four times, and cultured in fresh medium. HIV p24 antigen was determined at days 7 and 10 postinfection. CD4 U87 cells were included in each experiment as a control. The TCID50 of each supernatant tested for coreceptor usage on CD4-CXCR4 and CD4-CCR5 U87 cells was calculated by the method of Kärber (27).

Immunostaining of CXCR4 and CCR5.

After incubation with mouse immunoglobulin G1 control (679.1Mc7; Beckman Coulter), cells were immunostained by monoclonal antibodies 12G5-phycoerythrin (PE) for CXCR4 (BD-Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.), 2D7-PE for CCR5 (BD-Pharmingen), or immunoglobulin G1-PE (679.1Mc7; Beckman Coulter). Immunostaining was analyzed with an XL-4C cytofluorometer (Beckman Coulter).

Determination of CXCR4 mRNA levels using real-time PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from 107 thymocytes with an RNeasy DNase extraction minikit (Qiagen S.A.). RNAs were reverse transcribed in a 20-μl reaction volume by using a TaqMan reverse transcription kit and random hexamers (Perkin-Elmer Corp., PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). Reverse transcription was performed on a GeneAmp PCR system 9700 (PE Applied Biosystems) for 30 min at 48°C. Quantitative PCR was performed in special optical 96-well microtiter plates (PE Applied Biosystems) on an ABI Prism 7700 sequence detector system (PE Applied Biosystems). CXCR4 cDNA amplifications were performed with previously described oligonucleotides (25) and the SYBR Green PCR master mix (PE Applied Biosystems). To normalize for differences in the amount of total RNA added to the reaction mixture, quantification of 18S RNA with primers and probes purchased from PE Applied Biosystems was performed. Reverse transcriptions were performed in duplicate, and each reverse transcription product was submitted to real-time PCR at two dilutions.

Actin polymerization.

The function of CXCR4 was evaluated by monitoring actin polymerization following the addition of SDF-1α as previously described (9, 23). Briefly, 107 thymocytes per ml were incubated at 37°C in RPMI medium containing 10 mM HEPES and SDF-1α (1 μg/ml). Every 15 s, 100 μl of cell suspension was added to 400 μl of 100 mM fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled phalloidin (Sigma), 0.125 mg of l-α-lysophosphatidylcholine (Sigma)/ml, and 4.5% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline. Fixed cells were analyzed with an XL-4C cytofluorometer (Beckman Coulter). Similar experiments were performed to evaluate the actin polymerization induced through CCR5. For this purpose, 100 ng of MIP-1α/ml was used as a ligand.

Detection of SDF-1α levels.

SDF-1α levels were determined by a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Quantikine human SDF-1α immunoassay; R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis.

Because of the variability in the studied parameters displayed by the different thymuses from different donors, we performed statistical analyses using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. The level of significance was set at a P value of <0.05.

RESULTS

CXCR4 is highly expressed on thymocytes in contrast to CCR5, and CXCR4 levels are higher on immature (CD4−/+ CD8− CD3−) than on mature (CD4+ CD8− CD3−) thymocytes.

We first analyzed the specific expression of CXCR4 and CCR5, the major HIV coreceptors, on the two subsets of thymocytes able to produce the virus in the thymic microenvironment, namely, mature SP CD4+ and intermediate (CD4+ CD8− CD3−) thymocytes. The levels of expression of CXCR4 and CCR5 were determined by flow cytometry at the surfaces of freshly isolated mature SP CD4+ and immature (isolated for technical convenience as a pool of intermediate and TN) thymocytes. In the experiment whose results are shown in Fig. 1, CXCR4 was expressed on 88% of immature thymocytes, with a mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of 11.6, and on 56% of mature thymocytes, with an MFI of 1.5. The proportion of labeled cells obtained from 13 independent experiments performed on thymuses from individual donors ranged from 86 to 97% (median, 94%) with an MFI of 4.1 to 12.9 (median, 7.3) for immature CD4 thymocytes and from 17 to 70% (median, 44%) with an MFI of 0.36 to 4.2 (median, 1.3) for mature thymocytes. These data indicate that CXCR4 is highly expressed on the two cell populations, but this level was significantly higher on immature than on mature thymocytes (P < 0.001). In contrast, expression of CCR5 was similarly low (P = 0.7) in both populations. The rate of CCR5-labeled cells ranged between 1 and 19% (median, 6.9%), with an MFI between 0.02 and 0.4 (median, 0.3). These levels of coreceptor expression on thymocytes were compared to that on CD4+ cells within activated PBMC, which are well known as efficient target cells for both X4 and R5 viruses. At the time when we usually start HIV infection and under the proper conditions for activation (see Materials and Methods), 91% of these peripheral CD4+ cells expressed CXCR4 and 3.3% expressed CCR5. However, these levels of expression varied in culture towards a decrease of CXCR4-labeled (78%) and an increase of CCR5-labeled (51%) cells when IL-2 culture was prolonged (for instance, after 14 days), as already reported (6, 10).

FIG. 1.

Comparison of the levels of expression of CXCR4 and CCR5 in mature SP CD4+ and immature CD4−/+ CD8− CD3− thymocytes. Immunostainings of CXCR4 and CCR5 were performed on freshly isolated thymocytes and analyzed by flow cytometry. White area indicates isotypic control. Percentages of labeled cells are given. The results are representative of independent experiments carried out with thymuses from 13 donors.

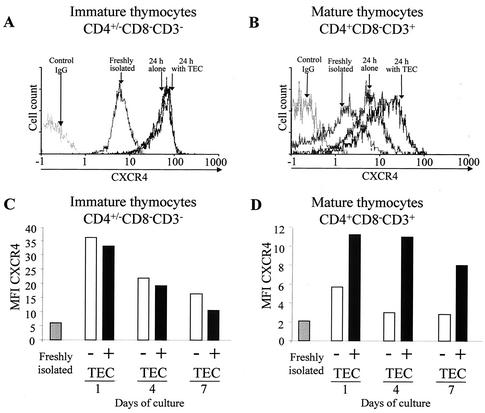

TEC upregulate CXCR4 expression in mature thymocytes.

We next examined whether TEC-thymocyte interaction, which favors HIV replication, may regulate coreceptor expression in thymocytes. Flow cytometry analysis of CXCR4 cell surface expression was performed on mature and immature thymocytes that had been either freshly isolated or cultured for 24 h alone or with TEC as previously described (47). A significant increase of CXCR4 expression was detected on the mature (P < 0.01) as well as on the immature (P < 0.01) thymocytes after 24 h in culture, as shown by the shift of the peak of CXCR4-labeled cells (Fig. 2A and B). This increase, observed when thymocytes were removed from the thymic microenvironment, suggested that some factor(s) present in the thymic microenvironment negatively regulates CXCR4. It should be pointed out that the effect of the negative regulation is lower for the mature thymocytes (P < 0.001). This may reflect the fact that interaction with TEC significantly increased CXCR4 expression in mature (P < 0.01) but not immature thymocytes (Fig. 2A and B), suggesting that some positive factor(s) secreted by TEC plays a role in CXCR4 expression in mature thymocytes but has no significant effect on immature thymocytes. This is indeed the case, since TEC increased CXCR4 expression in mature (Fig. 2B) but not in immature (Fig. 2A) thymocytes. The absence of an effect of TEC in immature thymocytes is not due to maximum levels of CXCR4 being already present, since TEC could not prevent the decrease of CXCR4 observed during prolonged culture (Fig. 2C). In contrast, TEC partially counteracted this decrease when it occurred on mature thymocytes (Fig. 2D).

FIG. 2.

Influence of TEC on CXCR4 expression in mature SP CD4+ and immature CD4−/+ CD8− CD3− thymocytes. Cell surface expression of CXCR4 was analyzed on immature (A) and mature (B) thymocytes by flow cytometry at the time of isolation or after 24 h in culture alone or with TEC. Immunostaining of CXCR4 was determined in immature and mature thymocytes just after isolation or after 1, 4, or 7 days of culture with or without TEC. (C and D) Results are shown as MFI of CXCR4-labeled cells. The experiment presented here is representative of independent experiments carried out with thymuses from five donors.

SDF-1α and IL-7 secreted by TEC have opposite effects on the modulation of CXCR4 expression on thymocytes.

We next investigated the factors secreted by TEC that are involved in the regulation of CXCR4 expression in thymocytes. Since an increase of CXCR4 expression on thymocyte surfaces was detectable by 3 h in culture and culminated at 12 h (data not shown), we postulated that a putative negative regulatory factor might act by masking or causing internalization of CXCR4, as has been described for SDF-1α (3, 36, 52). Indeed, we detected this chemokine in the supernatants of TEC cultures (mean of 190 pg/ml/105 cells after 4 days in culture). The production of this chemokine by TEC is in agreement with a recent report (22) showing SDF-1α staining in epithelial cells in sections of human thymus. As shown in Fig. 3A and B, in both mature and immature thymocytes, SDF-1α inhibited in a dose-dependent manner the increase of CXCR4 expression induced during the culture. Even though TEC are able to secrete this negative regulatory factor, their interaction with mature thymocytes results in an overall positive regulatory effect. Therefore, we considered the possibility that additional factors present in the thymic microenvironment might act to increase CXCR4 expression. We particularly focused on the cytokines that we have previously shown to induce HIV-1 replication in thymocytes, namely IL-7, IL-6, IL-1, TNF, and GM-CSF (11). As shown in Fig. 3B, among these cytokines, only IL-7 was able to enhance CXCR4 expression on mature and immature thymocytes (P < 0.01). This effect was weak but significant in immature thymocytes (P < 0.01). These data correlate with IL-7 receptor (IL-7R) expression levels, which are higher on mature than on immature thymocytes, as previously shown (19). A dose-dependent effect of this cytokine was demonstrated on the mature subpopulation, with an optimal effect at 1.25 ng/ml (Fig. 3B). We then determined the effects on CXCR4 expression following cultivation of thymocytes in the presence of both SDF-1α and IL-7. As shown in Fig. 3C, similar to the results at 24 h of cultivation mentioned above, a dose of 0.1 μg of SDF-1α/ml led to about 50% inhibition of CXCR4 expression on the immature and mature populations at 12, 24, and 84 h. This decrease was overcome in mature (but not immature) thymocytes by IL-7 at a concentration of 1.25 ng/ml. In conclusion, SDF-1α exerts a negative regulatory effect on CXCR4 expression on the two subpopulations, whereas IL-7 overcomes this effect mainly in mature thymocytes.

FIG. 3.

Effects of SDF-1α and IL-7 on CXCR4 expression in mature SP CD4+ and immature CD4−/+ CD8− CD3− thymocytes. Cell surface expression CXCR4 was analyzed by flow cytometry on immature or mature thymocytes, freshly isolated and after 24 h in culture in the presence of various concentrations of SDF-1α (A), after 24 h in culture in the presence of various cytokines (10 ng/ml each or the indicated concentrations of IL-7) (B), or freshly isolated and after 12, 36, and 84 h in the presence of SDF-1α (0.1 μg/ml) or a combination of SDF-1α (0.1 μg/ml) and IL-7 (1.25 ng/ml) (C). The results are shown as MFI of CXCR4-labeled cells and are expressed as means plus standard deviations of triplicate values for each thymus. The results are representative of independent experiments performed with thymuses from three donors.

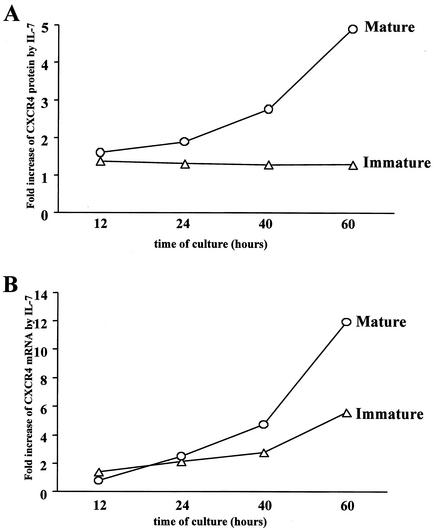

IL-7 positively regulates CXCR4 expression at the RNA level in mature thymocytes.

To further investigate the possible regulatory role of IL-7 on CXCR4 expression at the transcriptional level, we determined the kinetics of CXCR4 mRNA expression in mature and immature thymocytes in the presence or absence of IL-7 (Fig. 4B). We analyzed in parallel the levels of cell surface CXCR4 protein (Fig. 4A). The values for mRNA or CXCR4 protein in the presence of IL-7 were expressed as increase (-fold) compared with levels in untreated cells. As shown in Fig. 4B, in the mature thymocytes, a significant increase in CXCR4 mRNA levels (P < 0.03) was observed at 40 and 60 h of culture. This was correlated with an increase at the CXCR4 protein levels (P < 0.05). In immature thymocytes, as shown before, the increase of CXCR4 protein was lower (increase, 1.3-fold) and correlated here with a lower increase at the mRNA level. The difference in mRNA increase after 60 h in culture between mature and immature thymocytes was significant (P < 0.03).

FIG. 4.

Upregulation of CXCR4 protein and mRNA levels in mature SP CD4+ and immature CD4−/+ CD8− CD3− thymocytes by IL-7. CXCR4 expression was monitored at the protein (A) and mRNA (B) levels in mature and immature thymocytes after 12, 24, 40, and 60 h in culture in the presence or absence of IL-7 (10 ng/ml). (A) CXCR4 protein expression level was determined by CXCR4 cell surface immunostaining and analysis of labeled cells by flow cytometry. The results are shown as increase in MFI induced by IL-7 compared to untreated cells. (B) CXCR4 mRNA levels were determined by using a real-time kinetic quantitative reverse transcription-PCR. To normalize for differences in the amounts of total RNA, 18S rRNA was amplified as a control. The results are shown as increase of the normalized amount of CXCR4 mRNA induced by IL-7 compared to the amount in untreated cells. The data are representative of independent experiments carried out with thymuses from four donors.

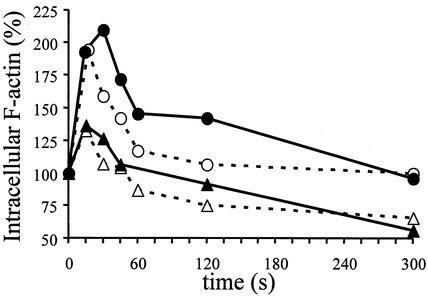

IL-7 increases CXCR4 signaling, leading to actin polymerization in mature thymocytes.

CXCR4 can regulate HIV entry by internal signaling, in particular by inducing actin polymerization, because the entry of the virus needs disintegration and reconstitution of the membrane structure, which are associated with actin turnover (24). Therefore, we investigated whether IL-7, which increases CXCR4 expression, might also participate to increase or prolong the induction of actin polymerization through CXCR4 binding. Since the level of IL-7R was much higher on mature than on immature thymocytes (19), we hypothesized that IL-7 might sustain signaling through CXCR4 preferentially in mature thymocytes. SDF-1α was used as a ligand to reveal the capacity of signaling of CXCR4. The kinetics of actin polymerization were determined in immature and mature thymocytes following culture for 40 h in the presence or absence of IL-7. This period in culture is sufficient to free the IL-7R, which was masked or internalized following interaction with IL-7 within the microenvironment (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 5, actin polymerization, as determined by immunostaining of filamentous actin (F actin), was rapidly induced following binding of SDF-1α to its receptor. This induction occurred at a higher level in mature than in immature thymocytes (P < 0.03) in the absence of IL-7, and IL-7 increased and prolonged this induction only in mature thymocytes (P < 0.01).

FIG. 5.

Influence of IL-7 on CXCR4 signaling leading to actin polymerization in mature SP CD4+ and immature CD4−/+ CD8− CD3− thymocytes. Thymocytes were cultured for 40 h in the presence (solid lines) or absence (dashed lines) of 10 ng of IL-7/ml. Immunostaining of intracellular F actin was performed with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled phalloidin and was analyzed by flow cytometry after the addition of 1 μg of SDF-1α/ml at time zero, in immature (triangles) and mature (circles) thymocytes. Results are shown as percent intracellular F-actin (MFI) relative to the value before addition of SDF-1α. The data are representative of independent experiments carried out with thymuses from five donors.

We also tried to investigate the kinetics of actin polymerization following the ligation of MIP-1α (the most specific ligand of CCR5) with CCR5. No consistent signal was observed in any experimental condition (data not shown).

These data suggest that entry of X4 viruses might be favored over that of R5 viruses in thymocytes and particularly in mature thymocytes following exposure to IL-7.

The selection of X4 versus R5 viruses was particularly favored in mature thymocytes compared to that observed in immature thymocytes or PBMC.

Since IL-7 upregulates CXCR4 expression and signaling in mature thymocytes, these cells might have a higher propensity to favor replication of X4 viruses. Nevertheless, the higher CXCR4 constitutive level expressed on immature thymocytes might compensate for the lower signaling capacity and might also permit high-level selection of X4 variants. We thus investigated the capacity of each subpopulation to favor X4 virus replication compared to that of PBMC.

The two populations of thymocytes or PBMC were each infected with the molecular clones pNL4-3 or pNLAD8. These two viruses differ from each other only in the env gene, which confers CXCR4 or CCR5 tropism, respectively. The multiplicities of infection (MOI) used for NL4-3 and NLAD8 (respectively, 1.6 × 10−4 and 2.8 × 10−3) were chosen to obtain consistent levels of replication, even with NLAD8, despite the low level of CCR5 coreceptors on thymocytes. The same MOI were also used to infect the PBMC. In order to evaluate the minimal ratio necessary to observe any significant selection, we also performed infections with a mixture of NL4-3 and NLAD8 in known proportions (X4/R5 ratio, 1/103, 1/104, or 1/105). Each distinct infected cell population was then cultured in the optimal conditions required for virus replication. Therefore, the infected thymocytes were cultured in the presence of IL-7 and TNF and the PBMC were cultured with IL-2 (as described in Materials and Methods).

We also verified that IL-7 has no direct effect on the level of HIV replication or on selection of X4 variants on activated T lymphocytes. Indeed we treated IL-2-PHA-activated PBMC from two healthy donors with IL-7 prior to infection with NL4-3 or NLAD8. IL-7 did not modify the level of replication of NL4-3 or of NLAD8 (data not shown).

Since the duration of the culture was 25 days, fresh thymocytes or PBMC were added to the culture at day 12, in order to provide new targets for the virus. Kinetics of virus replication was established for each cell type and for each viral inoculum by determination of p24 concentration in the culture supernatant (Fig. 6A, C, and E). To characterize the evolution of viral coreceptor usage during cell culture, we determined the ability of viral supernatants, before infection (initial inoculum) and at the end of the culture, to infect U87 cells coexpressing CD4 and CXCR4 or CD4 and CCR5. Viral tropism evolution was evaluated by calculating the ratios of viral titer (X4/R5) obtained in the two cell lines.

FIG. 6.

Comparison of mature SP CD4+ thymocytes, immature CD4−/+ CD8− CD3− thymocytes, and PBMC in their capacity to select X4 (NL4-3) versus R5 (NLAD8) viruses. (A, C, and E) Kinetics of HIV replication in mature (A) and immature (C) thymocytes and in PBMC (E). Cells were infected at MOIs of 1.6 × 10−4 for NL4-3 (filled circle), 2.8 × 10−3 for NLAD8 (filled triangle), or 2.8 × 10−3 for a mixture of both at TCID50 ratios (NL4-3/NLAD8) of 1/105 (open triangles), 1/104 (open squares), and 1/103 (open circles). Infected thymocytes were cultured with IL-7 (10 ng/ml) and TNF-α (10 ng/ml). PHA-IL-2-activated PBMC were infected and maintained with IL-2 (540 IU/ml). Freshly isolated thymocytes or activated PBMC were added to the cultures of infected thymocytes or PBMC every 12 days in order to provide new targets for the virus. HIV replication was determined by measuring the p24gag concentration in the culture supernatants every 3 or 4 days. (B, D, and F) Tropism of viruses recovered from the supernatants of infected mature (B) and immature (D) thymocytes and in PBMC (F). Supernatants of thymocytes or PBMC infected with virus mixtures at ratios of 1/105, 1/104, and 1/103 were harvested at day 21 for thymocytes and day 24 for PBMC. These supernatants and the initial mixtures used for infection (initial inoculum) were serially diluted and used to infect CD4-CXCR4 and CD4-CCR5 U87 cells. Replication of X4 and R5 viruses was determined by measuring the p24gag concentrations in culture supernatants at day 7. X4 and R5 TCID50 were then calculated by the method of Kärber (27). The ratios of TCID50 per milliliter for X4 versus R5 are given above the bars. ns, no significant ratio (<0.02) due to a too-low value for CD4-CXCR4 U87 cells.

Despite the higher MOI, NLAD8 replicated less efficiently than NL4-3 in both mature and immature thymocytes (Fig. 6A and C), whereas the replication levels of the two viruses were similar in PBMC (Fig. 6E).

Infection of mature thymocytes with the mixtures (X4/R5, 1/103, 1/104, or 1/105) rapidly led to replication levels higher than those observed with NLAD8 used alone, in both cell populations. The replication level attained with the X4/R5 mixtures at ratios of 1/103 and 1/104 was of the same order of magnitude as that observed with NL4-3 alone, suggesting an enrichment of X4 versus R5 virus. Moreover, TCID50 determined in CD4 CXCR4 and CCR5 U87 cells clearly demonstrated that mature thymocytes initially inoculated with mixtures containing 103 and 104 times more R5 than X4 viruses produced 16 and 350 times more X4 than R5 after 21 days of culture (Fig. 6B). In the immature thymocytes, an enrichment of X4 viruses was also observed at day 21 postinfection but to a lower extent than in mature cells (Fig. 6D and B). In PBMC, the X4/R5 TCID50 ratio balanced towards a similar level of replication of X4 and R5 variants (Fig. 6F). Thus, it appears that, compared to PBMC, mature and to a lesser extent immature thymocytes are more efficient in selecting replication of X4 versus R5 virus.

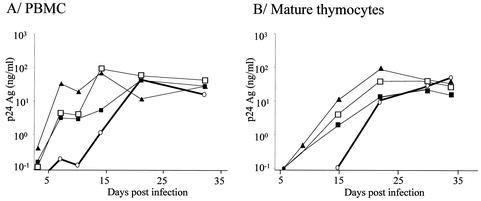

Mature thymocytes favor the emergence of X4 variants from an R5 primary isolate.

To determine whether emergence of X4 variants could occur after replication of primary isolates in mature thymocytes, four R5 clinical isolates with no detectable X4 variants, according to their inability to grow in CD4-CXCR4 U87 cells, were inoculated onto mature thymocytes at the highest available titer (Table 1). The origin of each viral isolate and its coreceptor usage evolution are detailed in Materials and Methods and in Table 1. All four R5 isolates efficiently replicated in PBMC and in mature thymocytes (Fig. 7). Viruses obtained at day 32 postinfection were tested for their coreceptor usage.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of tropism evolution of primary isolates in PBMC or mature thymocytesa

| Isolate | Origin | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial tropism

|

Final tropism

|

||||||

| R5 | X4 | PBMC

|

Thymocytes

|

||||

| R5 | X4 | R5 | X4 | ||||

| V.CT8 | Vietnam | 1.8 × 102 | <101 | 3.2 × 102 | <101 | 1 × 103 | 2 × 102 |

| 11111D | Central African Republic | 3.2 × 103 | <101 | 3.2 × 103 | <101 | 3.2 × 104 | <101 |

| J2758 | Italian cohort | 3.2 × 102 | <101 | 5.6 × 103 | <101 | 5.6 × 102 | <101 |

| 9614C | Central African Republic | 5.6 × 104 | <101 | 1 × 103 | <101 | 5.6 × 102 | <101 |

The tropisms of viruses recovered from the supernatants of infected mature thymocytes or PBMC were determined at day 32 postinfection. Initial isolates and supernatants from day 32 were serially diluted and used to infect CD4-CXCR4- and CD4-CCR5-expressing U87 cells. ×4 and R5 virus replication was determined by measuring the p24gag concentration in the culture supernatants at day 7. The X4 and R5 values are TCID50/ml calculated by the method of Kärber (27). The threshold of detection on U87 cells is 101 TCID50/ml.

FIG. 7.

Kinetics of replication of the primary isolates described in Table 1 in PBMC or mature thymocytes. PBMC (A) and mature thymocytes (B) were infected with various primary HIV-1 isolates described in Table 1. Freshly isolated thymocytes or PHA-IL-2-activated PBMC were infected with the primary isolates at MOI of 1.6 × 10−3 for V.CT8 (open circles), 9.5 × 10−4 for 11111D (filled triangles), 3.5 × 10−4 for J2758 (open squares), and 2.25 × 10−3 for 9614C (filled squares). Infected thymocytes were cultured with IL-7 (10 ng/ml) and TNF-α (10 ng/ml). Infected PBMC were maintained with IL-2 (540 IU/ml). Freshly isolated thymocytes or activated PBMC were added to the cultures every 10 days in order to provide new targets for the virus. HIV replication was determined by measuring the p24gag concentration in the culture supernatants.

For one out of the four R5 isolates tested (V.CT8), X4 variants could be detected only in the supernatants of mature thymocytes (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

In the present report we studied the influence of the thymic microenvironment on the control of expression and signaling of CXCR4 and CCR5 in mature SP CD4+ and immature intermediate thymocytes, which were shown to allow virus replication in the presence of the cytokines of the thymic microenvironment. We also studied the consequences of this control on the capacity of these cells to replicate R5 or X4 HIV-1. Just after isolation, CCR5 is expressed at similarly low levels in mature SP CD4+ and immature thymocytes, while CXCR4 expression is much higher in both subsets, particularly in immature cells. The latter result is consistent with previous studies indicating that CXCR4 expression decreases with thymocyte maturation in cells freshly isolated from fetal thymuses (5) or from thymuses obtained after cardiac surgery in children (64). Careful examination of coreceptor expression in mature and immature thymocytes, cultured as isolated populations or in the presence of TEC, demonstrate that CXCR4 but not CCR5 (data not shown) expression is regulated by the thymic microenvironment. Indeed, the microenvironment taken as a whole exerts a negative regulatory effect on CXCR4 expression in the two subpopulations, whereas TEC alone increase CXCR4 expression essentially in the SP CD4+ thymocytes. The negative effect was very likely induced by SDF-1α, which we and others have found to be secreted by TEC (data not shown and reference 22). The negative effect of SDF-1α on CXCR4 expression likely results from the masking or the internalization of CXCR4 (3). Nevertheless, coculture between TEC and thymocytes resulted in a net increase of CXCR4 expression in mature cells, suggesting that factors involved in TEC-thymocyte interaction can overcome the negative effect of SDF-1α on CXCR4 expression. This increase was due to soluble factors secreted by TEC, since supernatant of TEC cultures had the same effect (data not shown). The factor(s) involved in the positive regulation of CXCR4 was searched for among those involved in HIV replication, such as TNF, IL-7, IL-6, IL-1, and GM-CSF (11). Among these cytokines, we identified one, IL-7, capable of enhancing CXCR4 expression and of overcoming the down-regulation of CXCR4 induced by SDF-1α. This enhancement correlates with the expression level of the IL-7R, which is much higher in mature than in immature thymocytes, as previously shown (19). Thus, the positive effect of TEC mainly on mature thymocytes underlines the possibility that IL-7 might be the main positive factor of the microenvironment. However, since IL-7-neutralizing antibodies are not available, we were unable to exclude the possibility that other factors may play a synergistic role. Furthermore, independently of their microenvironment, the thymocytes themselves might maintain a high level of CXCR4 through the secretion of IL-2 and IL-4, which have been shown to increase CXCR4 expression in mature thymocytes (42, 61; also data not shown).

We then attempted to elucidate the mechanisms by which IL-7 modulates expression and function of CXCR4. First, we demonstrated that the effect of IL-7 on CXCR4 expression takes place at the mRNA level and that this positive regulatory effect was more efficient in mature than in immature thymocytes in accordance with the IL-7R content. Second, we determined that SDF-1α, used as a ligand, induced CXCR4 signaling, leading to actin polymerization (24), more efficiently in mature than in immature thymocytes. IL-7 increased and prolonged this induction specifically in mature thymocytes. Since induction of actin polymerization was obtained especially in mature thymocytes even in the absence of the addition of exogenous IL-7, we suggest that IL-7, within the microenvironment, might increase CXCR4 function by inducing signaling molecules which might remain partially activated at the time chosen here for the actin polymerization assay (40 h after thymocyte isolation). Such an activated molecule might be protein kinase B, which was shown to be activated by IL-7 (59) and to prolong CXCR4 signaling (40). Addition of IL-7 to the culture medium might potentiate this mechanism.

The level of expression of CCR5 was not modified by any culture conditions (data not shown). However, the thymocytes secreted MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and RANTES (data not shown), and it is thus possible that these CC chemokines might maintain CCR5 expression at a low level. This possible autocrine regulation of CCR5 by the CC chemokines might explain why the addition of cytokines was unable to modify the level of CCR5. The binding of MIP-1α to CCR5 did not induce actin polymerization in the thymocytes, irrespective of the culture conditions. These data are reminiscent of the fact that MIP-1β is unable to induce significant chemotaxis of thymocytes (57).

In addition to the difference in the level of expression of CXCR4 and CCR5, the main difference in their activity suggested a possible selection in favor of X4 viruses, particularly in the mature thymocytes.

To evaluate the minimal proportion of X4 virus necessary for a possible selection, we first used mixtures of NL4-3 and NLAD8 in various proportions. The replication kinetics assay showed that an X4/R5 ratio of 1/104 was sufficient to preferentially produce X4 viruses after infection of thymocytes. This selective process was more efficient in mature than in immature thymocytes. The capacity of mature and immature thymocytes to enrich for X4 variants was higher than that of PBMC, since in these cells a lower proportion of X4 viruses was produced after 24 days. This was expected, since PBMC display a higher level of CCR5 than thymocytes (data not shown) and prolonged activation of CD4+ T cells from PBMC leads to a decrease in CXCR4 expression (6) and an increase in CCR5 expression (10). This difference could also be explained by the fact that CD4+ cells from PBMC are highly sensitive to X4-induced cytopathogenic effects (29) while X4 replication in thymocytes and especially in mature thymocytes is not associated with a high level of apoptosis of infected cells (19).

This selection of X4 variants in mature thymocytes was also observed when these cells were infected by one primary isolate out of four tested. In contrast, PBMC were unable to select X4 variants from this primary isolate. The fact that the other three primary isolates did not give rise to any X4 variants might be due to a real lack of X4 variants in the initial isolates or to a very high dilution of X4 viruses (X4/R5 ratio < 1/104). Indeed, we think that the selection of X4 viruses is mainly due to an enrichment of preexisting X4 variants rather than to mutational events in the env gene, since X4 variants could not be obtained from an R5 molecular clone, at least in vitro, over the culture period (even after 74 days of culture) (data not shown). However, the evolution by mutations, which is dependent upon a high number of replication cycles, is not excluded in vivo in the mature thymocytes because of their permanent activation state within their microenvironment (12) (in contrast to T lymphocytes, which are mostly resting).

Recent data in the literature indicate the potential use of the coreceptor CCR8 by HIV-1. However, none of the molecular clones or isolates used was able to productively infect CD4-CCR8 U87 cells (data not shown). This negative result strengthens the importance of the two main coreceptors, CXCR4 and CCR5, in the thymus.

In this paper, we emphasize the importance of the thymic microenvironment and particularly of IL-7 in the positive control of expression and signaling of CXCR4 and the fact that such a control favors the replication of X4 viruses in the thymus, mainly in mature thymocytes. This more effective replication of X4 variants might be particularly efficient in children, because they display a high thymic function.

This interpretation is supported by a series of published data. Children whose thymuses are infected progress rapidly towards AIDS (8, 26, 35, 38). This might be sometimes related to the fact that in infants infected by their seropositive mothers who progressed rapidly to AIDS (three of nine), X4 isolates appeared very early in the course of the disease (mean, 7.7 months after birth) (50). It is indeed a general observation that emergence of X4 viruses is often correlated with accelerated progress of the disease in children (13, 54) and adults (28, 43, 51, 58). However, the particularly fast clinical evolution in children with X4 variants has been explained (13) by increased T-cell depletion due to cell destruction (as in adults) but aggravated by an impairment of production of new T cells (again suggesting an insult to the thymus).

In middle-aged adults, the thymus, albeit less active, is still functional (17). Furthermore, 50% of adult HIV patients exhibit a rebound of thymic activity (56) capable of generating new naive T cells (53). Therefore, emergence of X4 variants in adult thymus is plausible, especially since high levels of IL-7 in plasma observed in HIV patients (39), which might reflect this rebound, have been associated with the emergence of X4 variants (33). Furthermore, it has been shown that X4 variants develop more in circulating naive T cells (7). As these cells are normally quiescent in the blood and may not support active replication, a proliferation step must take place. This happens to compensate for the destruction of CD4+ T cells (21) by the virus, and the number of infected naive T cells is therefore a function of the decline of the CD4+ T cells. In this hypothesis it is not clear when naive T cells become infected, although in the case of thymus infection, these naive cells may derive from infected thymocytes. In any case, X4 variants in the blood might require an amplification period before being detectable. The length of time necessary for this amplification might therefore be related to the number of infected recent thymic emigrants (which is higher in children) and the rate of CD4+ T cell loss (again higher in children). In conclusion, we think that infection of the thymus is a factor of acceleration of the appearance of X4 variants and thus of disease progression. This process might occur early in the course of the disease, for instance, in children whose thymuses were infected in utero, or later, since the thymus may also be infected at later stages (as shown in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques [46]).

The participation of the thymus is probably not the sole possibility to explain the emergence of X4 variants, especially in advanced disease. At this stage, the consequences of generalized immune activation (18) might influence the amplification of X4 viruses in the blood compartment.

Acknowledgments

N. Schmitt and L. Chêne contributed equally to this work.

We thank Sonia Berrih-Aknin (Hôpital Marie Lannelongue, Le Plessis-Robinson, France) and F. Leco (Hôpital Necker, Paris, France) for providing us with thymuses and Gabriella Scarlatti (San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan, Italy) and Elisabeth Menu (Institut Pasteur, Paris, France) for providing us with primary HIV-1 isolates. We thank R. H. Bassin and M. Derrien for careful reading of the manuscript and G. Pancino and M. C. Müller-Trutwin for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by the Agence Nationale pour la Recherche sur le SIDA (ANRS). L. Chêne was the recipient successively of a fellowship from Ensemble contre le SIDA (Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale, Paris, France) and of a fellowship from Pasteur-Weizmann, N. Schmitt was the recipient of a fellowship from the French Ministry of Education and Research (MENESR), and E. Guillemard was the recipient of a fellowship from the Agence Nationale pour la Recherche sur le SIDA (France).

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi, A., H. E. Gendelman, S. Koenig, T. Folks, R. Willey, A. Rabson, and M. A. Martin. 1986. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J. Virol. 59:284-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aldrovandi, G. M., G. Feuer, L. Gao, B. Jamieson, M. Kristeva, I. S. Chen, and J. A. Zack. 1993. The SCID-hu mouse as a model for HIV-1 infection. Nature 363:732-736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amara, A., S. L. Gall, O. Schwartz, J. Salamero, M. Montes, P. Loetscher, M. Baggiolini, J. L. Virelizier, and F. Arenzana-Seisdedos. 1997. HIV coreceptor downregulation as antiviral principle: SDF-1α-dependent internalization of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 contributes to inhibition of HIV replication. J. Exp. Med. 186:139-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berger, E. A., P. M. Murphy, and J. M. Farber. 1999. Chemokine receptors as HIV-1 coreceptors: roles in viral entry, tropism, and disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 17:657-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berkowitz, R. D., K. P. Beckerman, T. J. Schall, and J. M. McCune. 1998. CXCR4 and CCR5 expression delineates targets for HIV-1 disruption of T cell differentiation. J. Immunol. 161:3702-3710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bermejo, M., J. Martin-Serrano, E. Oberlin, M. A. Pedraza, A. Serrano, B. Santiago, A. Caruz, P. Loetscher, M. Baggiolini, F. Arenzana-Seisdedos, and J. Alcami. 1998. Activation of blood T lymphocytes down-regulates CXCR4 expression and interferes with propagation of X4 HIV strains. Eur. J. Immunol. 28:3192-3204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blaak, H., A. B. van't Wout, M. Brouwer, B. Hooibrink, E. Hovenkamp, and H. Schuitemaker. 2000. In vivo HIV-1 infection of CD45RA+CD4+ T cells is established primarily by syncytium-inducing variants and correlates with the rate of CD4+ T cell decline. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:1269-1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blanche, S., M. Tardieu, A. M. Duliege, C. Rouzioux, F. Le Deist, K. Fukunaga, M. Caniglia, C. Jacomet, A. Messiah, and C. Griscelli. 1990. Longitudinal study of 94 symptomatic infants with perinatally acquired human immunodeficiency virus infection. Evidence for a bimodal expression of clinical and biological symptoms. Am. J. Dis. Child. 144:1210-1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bleul, C. C., R. C. Fuhlbrigge, J. M. Casasnovas, A. Aiuti, and T. A. Springer. 1996. A highly efficacious lymphocyte chemoattractant, stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1). J. Exp. Med. 184:1101-1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bleul, C. C., L. Wu, J. A. Hoxie, T. A. Springer, and C. R. Mackay. 1997. The HIV coreceptors CXCR4 and CCR5 are differentially expressed and regulated on human T lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:1925-1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chêne, L., M. Nugeyre, E. Guillemard, N. Moulian, F. Barré-Sinoussi, and N. Israël. 1999. Thymocyte-thymic epithelial cell interaction leads to high-level replication of human immunodeficiency virus exclusively in mature CD4+ CD8− CD3+ thymocytes: a critical role for tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-7. J. Virol. 73:7533-7542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chêne, L., M. T. Nugeyre, F. Barré-Sinoussi, and N. Israël. 1999. High-level replication of human immunodeficiency virus in thymocytes requires NF-κB activation through interaction with thymic epithelial cells. J. Virol. 73:2064-2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Correa, R., and M. A. Munoz-Fernandez. 2001. Viral phenotype affects the thymic production of new T cells in HIV-1-infected children. AIDS 15:1959-1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis, A. E., Jr. 1984. The histopathological changes in the thymus gland in the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 437:493-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng, H., R. Liu, W. Ellmeier, S. Choe, D. Unutmaz, M. Burkhart, P. Di Marzio, S. Marmon, R. E. Sutton, C. M. Hill, C. B. Davis, S. C. Peiper, T. J. Schall, D. R. Littman, and N. R. Landau. 1996. Identification of a major co-receptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature 381:661-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deng, H. K., D. Unutmaz, V. N. KewalRamani, and D. R. Littman. 1997. Expression cloning of new receptors used by simian and human immunodeficiency viruses. Nature 388:296-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Douek, D. C., R. D. McFarland, P. H. Keiser, E. A. Gage, J. M. Massey, B. F. Haynes, M. A. Polis, A. T. Haase, M. B. Feinberg, J. L. Sullivan, B. D. Jamieson, J. A. Zack, L. J. Picker, and R. A. Koup. 1998. Changes in thymic function with age and during the treatment of HIV infection. Nature 396:690-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feinberg, M. B., J. M. McCune, F. Miedema, J. P. Moore, and H. Schuitemaker. 2002. HIV tropism and CD4+ T-cell depletion. Nat. Med. 8:537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guillemard, E., M. T. Nugeyre, L. Chêne, N. Schmitt, C. Jacquemot, F. Barré-Sinoussi, and N. Israël. 2001. Interleukin-7 and infection itself by human immunodeficiency virus 1 favor virus persistence in mature CD4+CD8−CD3+ thymocytes through sustained induction of Bcl-2. Blood 98:2166-2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haynes, B. F., L. P. Hale, K. J. Weinhold, D. D. Patel, H. X. Liao, P. B. Bressler, D. M. Jones, J. F. Demarest, K. Gebhard-Mitchell, A. T. Haase, and J. A. Bartlett. 1999. Analysis of the adult thymus in reconstitution of T lymphocytes in HIV-1 infection. J. Clin. Investig. 103:453-460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hazenberg, M. D., J. W. Stuart, S. A. Otto, J. C. Borleffs, C. A. Boucher, R. J. de Boer, F. Miedema, and D. Hamann. 2000. T-cell division in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 infection is mainly due to immune activation: a longitudinal analysis in patients before and during highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). Blood 95:249-255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hernandez-Lopez, C., A. Varas, R. Sacedon, E. Jimenez, J. J. Munoz, A. G. Zapata, and A. Vicente. 2002. Stromal cell-derived factor 1/CXCR4 signaling is critical for early human T-cell development. Blood 99:546-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howard, T. H., and W. H. Meyer. 1984. Chemotactic peptide modulation of actin assembly and locomotion in neutrophils. J. Cell Biol. 98:1265-1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iyengar, S., J. E. Hildreth, and D. H. Schwartz. 1998. Actin-dependent receptor colocalization required for human immunodeficiency virus entry into host cells. J. Virol. 72:5251-5255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jinquan, T., H. H. Jacobi, C. Jing, C. M. Reimert, S. Quan, S. Dissing, L. K. Poulsen, and P. S. Skov. 2000. Chemokine stromal cell-derived factor 1α activates basophils by means of CXCR4. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 106:313-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joshi, V. V., J. M. Oleske, S. Saad, C. Gadol, E. Connor, R. Bobila, and A. B. Minnefor. 1986. Thymus biopsy in children with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 110:837-842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kärber, G. 1931. Beitrag zur kollektiven behandlung pharmakogisher reihenvesuche. Arch. Exp. Pathol. Pharmakol. 162:956-959. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koot, M., R. van Leeuwen, R. E. de Goede, I. P. Keet, S. Danner, J. K. Eeftinck Schattenkerk, P. Reiss, M. Tersmette, J. M. Lange, and H. Schuitemaker. 1999. Conversion rate towards a syncytium-inducing (SI) phenotype during different stages of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection and prognostic value of SI phenotype for survival after AIDS diagnosis. J. Infect. Dis. 179:254-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwa, D., J. Vingerhoed, B. Boeser-Nunnink, S. Broersen, and H. Schuitemaker. 2001. Cytopathic effects of non-syncytium-inducing and syncytium-inducing human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants on different CD4+-T-cell subsets are determined only by coreceptor expression. J. Virol. 75:10455-10459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lackner, A. A., P. Vogel, R. A. Ramos, J. D. Kluge, and M. Marthas. 1994. Early events in tissues during infection with pathogenic (SIVmac239) and nonpathogenic (SIVmac1A11) molecular clones of simian immunodeficiency virus. Am. J. Pathol. 145:428-439. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lecossier, D., F. Bouchonnet, P. Schneider, F. Clavel, and A. J. Hance. 2001. Discordant increases in CD4+ T cells in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients experiencing virologic treatment failure: role of changes in thymic output and T cell death. J. Infect. Dis. 183:1009-1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lederman, M. M., and H. Valdez. 2000. Immune restoration with antiretroviral therapies: implications for clinical management. JAMA 284:223-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Llano, A., J. Barretina, A. Gutierrez, J. Blanco, C. Cabrera, B. Clotet, and J. A. Este. 2001. Interleukin-7 in plasma correlates with CD4 T-cell depletion and may be associated with emergence of syncytium-inducing variants in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-positive individuals. J. Virol. 75:10319-10325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Menu, E., T. X. Truong, M. E. Lafon, T. H. Nguyen, M. C. Müller-Trutwin, T. T. Nguyen, A. Deslandres, G. Chaouat, Q. T. Duong, B. K. Ha, H. J. Fleury, and F. Barré-Sinoussi. 1996. HIV type 1 Thai subtype E is predominant in South Vietnam. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 12:629-933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meyers, A., A. Shah, R. H. Cleveland, W. R. Cranley, B. Wood, S. Sunkle, S. Husak, and E. R. Cooper. 2001. Thymic size on chest radiograph and rapid disease progression in human immunodeficiency virus 1-infected children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 20:1112-1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Misse, D., M. Cerutti, N. Noraz, P. Jourdan, J. Favero, G. Devauchelle, H. Yssel, N. Taylor, and F. Veas. 1999. A CD4-independent interaction of human immunodeficiency virus-1 gp120 with CXCR4 induces their cointernalization, cell signaling, and T-cell chemotaxis. Blood 93:2454-2462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muller-Trutwin, M. C., M. L. Chaix, F. Letourneur, E. Begaud, D. Beaumont, A. Deslandres, B. You, J. Morvan, C. Mathiot, F. Barre-Sinoussi, and S. Saragosti. 1999. Increase of HIV-1 subtype A in Central African Republic. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 21:164-171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nahmias, A. J., W. S. Clark, A. P. Kourtis, F. K. Lee, G. Cotsonis, C. Ibegbu, D. Thea, P. Palumbo, P. Vink, R. J. Simonds, S. R. Nesheim, et al. 1998. Thymic dysfunction and time of infection predict mortality in human immunodeficiency virus-infected infants. J. Infect. Dis. 178:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Napolitano, L. A., R. M. Grant, S. G. Deeks, D. Schmidt, S. C. De Rosa, L. A. Herzenberg, B. G. Herndier, J. Andersson, and J. M. McCune. 2001. Increased production of IL-7 accompanies HIV-1-mediated T-cell depletion: implications for T-cell homeostasis. Nat. Med. 7:73-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pallard, C., A. P. Stegmann, T. van Kleffens, F. Smart, A. Venkitaraman, and H. Spits. 1999. Distinct roles of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and STAT5 pathways in IL-7-mediated development of human thymocyte precursors. Immunity 10:525-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Papiernik, M., Y. Brossard, N. Mulliez, J. Roume, C. Brechot, F. Barin, A. Goudeau, J. F. Bach, C. Griscelli, R. Henrion, and R. Vazeux. 1992. Thymic abnormalities in fetuses aborted from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 seropositive women. Pediatrics 89:297-301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pedroza-Martins, L., K. B. Gurney, B. E. Torbett, and C. H. Uittenbogaart. 1998. Differential tropism and replication kinetics of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates in thymocytes: coreceptor expression allows viral entry, but productive infection of distinct subsets is determined at the postentry level. J. Virol. 72:9441-9452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Penn, M. L., J. C. Grivel, B. Schramm, M. A. Goldsmith, and L. Margolis. 1999. CXCR4 utilization is sufficient to trigger CD4+ T cell depletion in HIV-1-infected human lymphoid tissue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:663-668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Richman, D. D., and S. A. Bozzette. 1994. The impact of the syncytium-inducing phenotype of human immunodeficiency virus on disease progression. J. Infect. Dis. 169:968-974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosenzweig, M., D. P. Clark, and G. N. Gaulton. 1993. Selective thymocyte depletion in neonatal HIV-1 thymic infection. AIDS 7:1601-1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosenzweig, M., M. Connole, A. Forand-Barabasz, M. P. Tremblay, R. P. Johnson, and A. A. Lackner. 2000. Mechanisms associated with thymocyte apoptosis induced by simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Immunol. 165:3461-3468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rothe, M., L. Chêne, M. Nugeyre, F. Barré-Sinoussi, and N. Israël. 1998. Contact with thymic epithelial cells as a prerequisite for cytokines enhanced HIV-1 replication in thymocytes. J. Virol. 72:5852-5861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Savino, W., M. Dardenne, C. Marche, D. Trophilme, J.-M. Dupuy, D. Pekovic, N. Lapointe, and J.-F. Bach. 1986. Thymic epithelium in AIDS. An immunologic study. Am. J. Pathol. 122:302-307. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scarlatti, G., V. Hodara, P. Rossi, L. Muggiasca, A. Bucceri, J. Albert, and E. M. Fenyö. 1993. Transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) from mother to child correlates with viral phenotype. Virology 197:624-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scarlatti, G., E. Tresoldi, A. Bjorndal, R. Fredriksson, C. Colognesi, H. K. Deng, M. S. Malnati, A. Plebani, A. G. Siccardi, D. R. Littman, E. M. Fenyo, and P. Lusso. 1997. In vivo evolution of HIV-1 co-receptor usage and sensitivity to chemokine-mediated suppression. Nat. Med. 3:1259-1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schuitemaker, H., M. Koot, N. A. Kootstra, M. W. Dercksen, R. E. de Goede, R. P. van Steenwijk, J. M. Lange, J. K. Schattenkerk, F. Miedema, and M. Tersmette. 1992. Biological phenotype of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 clones at different stages of infection: progression of disease is associated with a shift from monocytotropic to T-cell-tropic virus population. J. Virol. 66:1354-1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Signoret, N., M. M. Rosenkilde, P. J. Klasse, T. W. Schwartz, M. H. Malim, J. A. Hoxie, and M. Marsh. 1998. Differential regulation of CXCR4 and CCR5 endocytosis. J. Cell Sci. 111:2819-2830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith, K. Y., H. Valdez, A. Landay, J. Spritzler, H. A. Kessler, E. Connick, D. Kuritzkes, B. Gross, I. Francis, J. M. McCune, and M. M. Lederman. 2000. Thymic size and lymphocyte restoration in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection after 48 weeks of zidovudine, lamivudine, and ritonavir therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 181:141-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spencer, L. T., M. T. Ogino, W. M. Dankner, and S. A. Spector. 1994. Clinical significance of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 phenotypes in infected children. J. Infect. Dis. 169:491-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stanley, S. K., J. M. McCune, H. Kaneshima, J. S. Justement, M. Sullivan, E. Boone, M. Baseler, J. Adelsberger, M. Bonyhadi, J. Orenstein, C. H. Fox, and A. S. Fauci. 1993. Human immunodeficiency virus infection of the human thymus and disruption of the thymic microenvironment in the SCID-hu mouse. J. Exp. Med. 178:1151-1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stoddart, C. A., T. J. Liegler, F. Mammano, V. D. Linquist-Stepps, M. S. Hayden, S. G. Deeks, R. M. Grant, F. Clavel, and J. M. McCune. 2001. Impaired replication of protease inhibitor-resistant HIV-1 in human thymus. Nat. Med. 7:712-718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Taylor, J. R., Jr., K. C. Kimbrell, R. Scoggins, M. Delaney, L. Wu, and D. Camerini. 2001. Expression and function of chemokine receptors on human thymocytes: implications for infection by human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 75:8752-8760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tersmette, M., J. M. Lange, R. E. Y. de Goede, F. de Wolf, J. K. M. Eeftink-Schattenkerk, P. T. Schellekens, R. A. Coutinho, J. G. Huisman, J. Goudsmit, and F. Miedema. 1989. Association between biological properties of human immunodeficiency virus variants and risk for AIDS and AIDS mortality. Lancet 1:983-985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thelen, M. 2001. Dancing to the tune of chemokines. Nat. Immunol. 2:129-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Theodore, T. S., G. Englund, A. Buckler-White, C. E. Buckler, M. A. Martin, and K. W. Peden. 1996. Construction and characterization of a stable full-length macrophage-tropic HIV type 1 molecular clone that directs the production of high titers of progeny virions. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 12:191-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Uittenbogaart, C. H., D. J. Anisman, B. D. Jamieson, S. Kitchen, I. Schmid, J. A. Zack, and E. F. Hays. 1996. Differential tropism of HIV-1 isolates for distinct thymocyte subsets in vitro. AIDS 10:9-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weiss, L., P. Ancuta, P. M. Girard, H. Bouhlal, A. Roux, N. H. Cavaillon, and M. D. Kazatchkine. 1999. Restoration of normal interleukin-2 production by CD4+ T cells of human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients after 9 months of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 180:1057-1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wykrzykowska, J. J., M. Rosenzweig, R. S. Veazey, M. A. Simon, K. Halvorsen, R. C. Desrosiers, R. P. Johnson, and A. Lackner. 1998. Early regeneration of thymic progenitors in rhesus macaques infected with simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Exp. Med. 187:1767-1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zaitseva, M. B., S. Lee, R. L. Rabin, H. L. Tiffany, J. M. Farber, K. W. Peden, P. M. Murphy, and H. Golding. 1998. CXCR4 and CCR5 on human thymocytes: biological function and role in HIV-1 infection. J. Immunol. 161:3103-3113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]