Abstract

Oxidation of n-alkanes in bacteria is normally initiated by an enzyme system formed by a membrane-bound alkane hydroxylase and two soluble proteins, rubredoxin and rubredoxin reductase. Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains PAO1 and RR1 contain genes encoding two alkane hydroxylases (alkB1 and alkB2), two rubredoxins (alkG1 and alkG2), and a rubredoxin reductase (alkT). We have localized the promoters for these genes and analyzed their expression under different conditions. The alkB1 and alkB2 genes were preferentially expressed at different moments of the growth phase; expression of alkB2 was highest during the early exponential phase, while alkB1 was induced at the late exponential phase, when the growth rate decreased. Both genes were induced by C10 to C22/C24 alkanes but not by their oxidation derivatives. However, the alkG1, alkG2, and alkT genes were expressed at constant levels in both the absence and presence of alkanes.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a ubiquitous bacterium that can be found associated with soil and aquatic environments and can behave as an opportunistic pathogen for animals and plants (17, 25). This ecological diversity is probably related to its ability to use a wide range of substrates as carbon and energy sources (25). Most P. aeruginosa strains isolated from both clinical and nonclinical environments can degrade n-alkanes (1, 31, 36). Alkanes are the most abundant family of hydrocarbons in crude oil and are generated by many plants and algae (20). Bacterial metabolism of n-alkanes normally proceeds via sequential oxidation of a terminal methyl group to render alcohols, aldehydes, and, finally, fatty acids (20). The best-characterized alkane degradation pathway is that of Pseudomonas putida GPo1 (32). In this case, the initial oxidation step is performed by an alkane hydroxylase system composed of a membrane-bound nonheme iron monooxygenase (commonly named alkane hydroxylase) and two soluble proteins, rubredoxin and rubredoxin reductase, which act as electron carriers between NADH and the hydroxylase. Genes encoding related enzymes have been found in several alkane-degrading bacteria (12, 13, 18, 23, 24, 31, 34).

P. putida GPo1 and Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 contain only one alkane hydroxylase (18, 32). However, other bacterial strains contain several alkane hydroxylases. In this case, the different alkane hydroxylases may have distinct properties or may be induced under different conditions. Acinetobacter sp. strain M1 contains two alkane hydroxylases, one of which oxidizes C12 to C16 n-alkanes, the other one showing a higher activity with C20 or larger alkanes (12). The expression of each hydroxylase is controlled by a specific transcription factor that responds to the alkanes recognized by the corresponding hydroxylase (29).

P. aeruginosa PAO1, whose genome has been sequenced (28), contains genes encoding two alkane hydroxylases, two rubredoxins, and a rubredoxin reductase homologous to those of P. putida GPo1 (Fig. 1A). All these genes encode enzymes that participate in the oxidation of n-alkanes (22, 23, 30), although the regulation of their expression has not been reported. The AlkB1 alkane hydroxylase oxidizes C16 to C24 n-alkanes, while AlkB2 is active on C12 to C20 n-alkanes (22). Therefore, the substrate specificity of the two enzymes overlaps substantially. This suggests that they may not be induced simultaneously, each one being present under different situations.

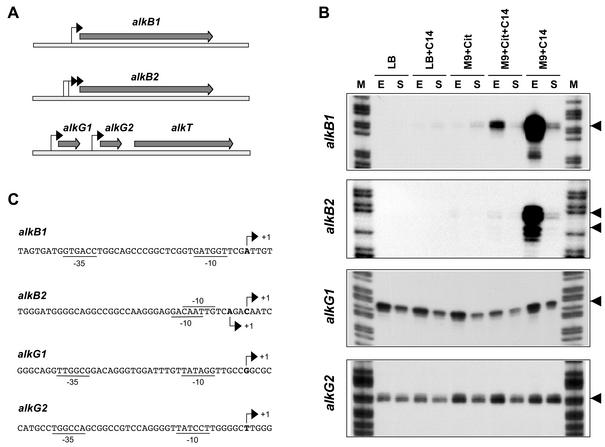

FIG. 1.

Promoters for alkB1, alkB2, alkG1, and alkG2 genes. (A) The genes encoding the two membrane-bound alkane hydroxylases, alkB1 and alkB2, are located on different sites of the chromosome. The genes encoding the two rubredoxins (alkG1 and alkG2) and the rubredoxin reductase (alkT) are clustered and map at a different site. Arrows indicate the promoters identified in this work. (B) Identification and expression of the promoters for the alkB1, alkB2, alkG1, and alkG2 genes in cells grown either in rich LB medium or in M9 minimal salts medium in the absence or presence of tetradecane (C14) or citrate (Cit). Cells were collected at either the exponential (A550 of 1.5) or stationary (A550 of 5) phase of growth (indicated as E and S, respectively). Transcripts originating upstream of the genes under study were analyzed by S1 nuclease protection assays; the 5′ ends of the probes used hybridized at positions +89, +56, +87, and +152 relative to the transcription start sites observed for promoters PalkB1, PalkB2, PalkG1, and PalkG2, respectively. Lane M, DNA size ladder. Arrows indicate the transcription start sites observed. No other bands were detected in the gels in addition to those shown. (C) Sequences of the promoters identified in P. aeruginosa strain RR1. The transcription start sites observed in panel B are indicated with arrows. Sequences at the −10 and −35 regions showing similarity (at least three matches) to those recognized by the vegetative RNA polymerase are underlined. The ATG translation start sites of alkB1, alkB2, alkG1, and alkG2 are located at positions +36, +35, +36, and +101, respectively.

To investigate this issue, we analyzed the expression of the components of the two P. aeruginosa alkane hydroxylases. Assays were performed on P. aeruginosa RR1, a strain isolated from an oil-contaminated site (36), and extended to P. aeruginosa PAO1, isolated from an infected wound (16).

Characterization of promoters for alkB1, alkB2, alkG1, alkG2, and alkT genes.

PCR analyses showed that P. aeruginosa RR1 contains genes homologous to those of P. aeruginosa PAO1 encoding the AlkB1 and AlkB2 alkane hydroxylases, the AlkG1 and AlkG2 rubredoxins, and the AlkT rubredoxin reductase. DNA segments encoding the 5′ regions of the strain RR1 alkB1 and alkB2 genes were PCR amplified and cloned. In the case of alkB1, a primer pair that allowed us to amplify a 425-bp DNA fragment spanning positions −336 to +89 relative to the alkB1 transcription start site (as determined in this work; see below) was used. This DNA fragment was cloned into pGEM-T Easy (Promega), generating plasmid pPB1R1. With primers containing targets for EcoRI, a 566-bp fragment spanning positions −185 to +381 relative to the alkB2 transcription start site (see below) was PCR amplified and cloned at the EcoRI site of pUC18 (21), yielding plasmid pBRR1. A similar strategy allowed us to obtain a 1.9-kbp DNA fragment including alkG1, alkG2, and the 5′ region of alkT (nucleotides −206, relative to the alkG1 transcription start site, to +1034, relative to alkT translation start site), which was cloned at the BamHI site of plasmid pUC19 (21), generating pRUB1.

Sequencing of these DNA regions showed very few differences between strains RR1 and PAO1. One base pair deletion was found at position −55 of the strain RR1 alkB1 gene. No differences were found at the promoter region of alkB2. The sequences of alkG1, alkG2, and the 5′ region of alkT were also identical to those of strain PAO1 except at the alkG1 promoter, where positions −2 and −15 were guanosine residues in RR1 and adenosines in PAO1.

To determine the transcription start site of each of these genes, P. aeruginosa RR1 was grown at 30°C either in rich Luria-Bertani (LB) medium or in M9 minimal salts medium (21), the latter supplemented with trace elements (2) and a carbon source (either 30 mM citrate, 1% [wt/vol] tetradecane, or a mixture of both). Total RNA was obtained from cells collected at either the exponential (A550 of 1.5) or the stationary (A550 of 5) phase of growth. The origin and amount of the transcripts corresponding to the genes under study were analyzed by S1 nuclease protection assays as described earlier (35, 37), with equal amounts of RNA in each sample. The single-stranded DNA probe used, which was added in a large excess to titrate the mRNA, was generated by linear PCR as described before (35), with plasmids pPB1R1 linearized with EcoRI (contains the promoter for alkB1), pPBRR1 cut with NdeI (contains the promoter for alkB2), or pRUB1 cut with BamHI (contains alkG1, alkG2, and the 5′ region of alkT) as the substrate.

As shown in Fig. 1B, strong signals were detected for the alkB1 and alkB2 genes in cells growing in minimal salts medium containing tetradecane as the carbon source and collected at the late exponential phase (A550 of 1.5). It should be noted that growth of P. aeruginosa RR1 on alkanes showed an initial exponential phase until the turbidity reached about 1.2, followed by a period of slower growth that ended when the turbidity reached 5 to 6, when the stationary phase became evident (an example can be seen in Fig. 2). For alkB1, a single band was detected corresponding to a promoter in which consensus boxes for the vegetative σ70 RNA polymerase could be recognized, although conservation was low (see Fig. 1C). For alkB2, two adjacent signals were observed, each composed of two or three bands (Fig. 1B). In both cases, the start site was preceded by −10 regions showing some similarity to the consensus for σ70 RNA polymerase, although no −35 consensus boxes were evident (Fig. 1C).

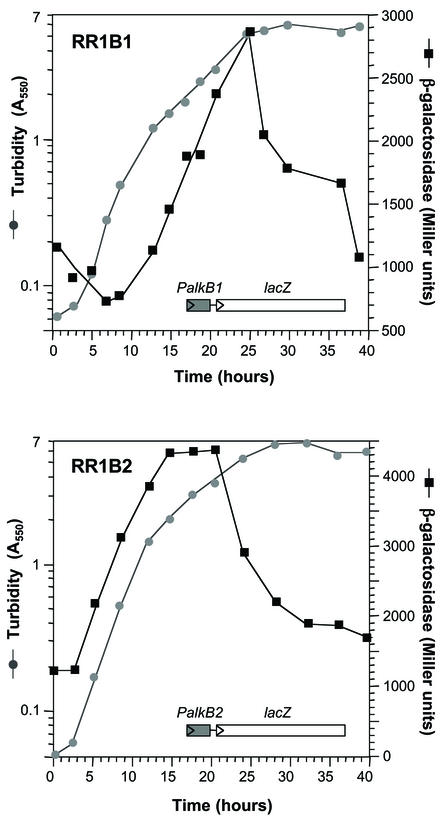

FIG. 2.

Expression of alkB1 and alkB2 throughout the growth phase. Strains RR1B1 (strain RR1 containing a PalkB1::lacZ transcriptional fusion) and RR1B2 (strain RR1 containing a PalkB2::lacZ transcriptional fusion) were grown in minimal salts M9 medium containing tetradecane as the carbon source. Samples were taken at different times, and the amount of β-galactosidase present was measured (solid squares). Cells were washed and resuspended in M9 medium without alkanes prior to turbidity measurements (gray circles) to avoid errors induced by nondissolved alkanes.

The presence of two moderately conserved −10 boxes suggests that the two signals correspond to overlapping promoters, although it cannot be ruled out that the smaller transcript derives from the larger one. However, since both behaved similarly in all our assays, they are referred to hereafter as PalkB2, and coordinates are given relative to the start site of the largest transcript, which was also the most abundant. The activity of promoters PalkB1 and PalkB2 decreased significantly when cells reached the stationary phase of growth (A550 of 5 to 6; Fig. 1B). No expression of the alkB1 and alkB2 genes was observed when cells were grown in rich LB medium or in minimal salts medium containing citrate as the carbon source, which indicates that their induction requires the presence of alkanes (Fig. 1B). However, addition of tetradecane to these culture media led to a low induction of the two promoters (with citrate) or even to no induction (with LB; Fig. 1B). This is indicative of a catabolic repression control induced by the components of the rich medium and by citrate.

A similar analysis of expression of the alkG1 and alkG2 genes, which encode two homologous rubredoxins, indicated that each is expressed from an independent promoter (Fig. 1B). In both cases, the −35 and −10 regions were rather similar to the consensus recognized by σ70 RNA polymerase (Fig. 1C). Expression was somewhat weaker at high turbidities but was independent of the absence or presence of tetradecane and was not repressed by the presence of citrate or by growth of cells in rich LB medium. No promoter could be found immediately upstream from alkT, which encodes the rubredoxin reductase. The probes used, which comprised the 5′ end of alkT and the complete alkG2 gene, were protected in their entire length from S1 nuclease attack (not shown), suggesting that alkT is expressed from the alkG2 promoter.

A putative rho-independent transcriptional terminator was present downstream of alkG1, but no such sequences were found between alkG2 and alkT. A reverse transcription-PCR analysis confirmed that alkT was expressed in cells growing in all the culture media analyzed, as it did for alkG2 (not shown). The use of an upstream primer hybridizing to alkG2 and a downstream primer hybridizing to alkT showed that transcripts running through alkG2 continued into alkT (not shown), further supporting that alkT is expressed from the promoter for alkG2. The constitutive expression of alkG1, alkG2, and alkT contrasts with the controlled expression of alkB1 and alkB2 and suggests that the three components of the alkane hydroxylase system are not present in stoichiometric amounts in induced cells. The ratio of AlkB, AlkG, and AlkT has been analyzed only for P. putida GPo1, where it was found to be 7:2.5:1 in spite of the fact that the three proteins are coordinately induced (27). This unbalanced stoichiometry suggests that the molecules of the membrane-bound hydroxylase share a limiting number of rubredoxin and rubredoxin reductase molecules, which are soluble proteins that can probably associate and dissociate from the membrane-bound hydroxylase.

Differential expression of alkB1 and alkB2 genes.

To gain further insight into the expression of alkB1 and alkB2, transcriptional fusions of promoters PalkB1 and PalkB2 to the lacZ reporter gene were constructed. In the case of PalkB1, a DNA fragment was PCR amplified from P. aeruginosa RR1 spanning positions −336 to +10 relative to the transcription start site (the translation start site is at position +36). The primers used introduced artificial sites for EcoRI and BamHI endonucleases, which served to clone the DNA fragment between the same sites of plasmid pUJ8 (6), yielding plasmid pPAH1β1. The PalkB1::lacZ fusion was excised from pPAH1β1 with NotI and cloned at the NotI site of pUT-mini-Tn5Sm (6), generating plasmid pPAH1β3.

A similar strategy was followed for promoter PalkB2. The DNA fragment cloned into pUJ8 spanned positions −185 to +23 relative to the alkB2 transcription start site (the translation start site is at position +35). The plasmid obtained was named pPAH2β1. This plasmid was cut with NotI, and the PalkB2::lacZ fusion was cloned at the NotI site of pUT-mini-Tn5Sm, generating pPAH2β3. The suicide plasmids containing the PalkB1::lacZ and PalkB2::lacZ fusions were introduced into P. aeruginosa RR1 by transformation (8) to deliver the fusions into the chromosome (these plasmids do not replicate in P. aeruginosa). Two transformants were selected for each fusion. Since in each case they generated similar levels of β-galactosidase when grown in the presence of tetradecane, only one of them was selected for further analyses.

The transformant containing the PalkB1::lacZ fusion was named RR1B1, while that containing the PalkB2::lacZ fusion was named RR1B2. To analyze the expression of the PalkB1 and PalkB2 promoters, strains RR1B1 and RR1B2 were grown in minimal salts medium containing tetradecane as the carbon source, and β-galactosidase activity was measured at several points of the growth phase as described earlier (15, 35). Promoter PalkB1 showed low activity during the early exponential phase of growth, when cells grew at a faster rate (Fig. 2). The activity of β-galactosidase did not increase until the cells approached the late exponential phase, at turbidities of about 1, when the growth rate decreased. At this time, β-galactosidase levels increased steadily and peaked at turbidities of about 5, when culture growth had ceased and the stationary phase was evident. At later times, β-galactosidase levels dropped in spite of the presence of nonmetabolized alkanes in the medium.

Interestingly, promoter PalkB2 showed a different behavior. It was activated as soon as the cells started to grow, and β-galactosidase levels increased steadily during the early exponential phase, reaching a plateau at turbidities of about 2, when the growth rate had decreased and cells had entered the late exponential phase of growth. The β-galactosidase levels remained high for some time but then declined before cell growth ceased. Cell growth continued until the turbidity reached values of 6 to 7, although β-galactosidase activity declined steadily. This expression pattern agrees with the results of the mRNA analyses presented in Fig. 1B. In both cases, the S1 nuclease protection assays were performed with RNA obtained from cells collected at either the late exponential phase (A550 of about 1.5) or the stationary phase (A550 of about 5). Therefore, the results indicate that the two P. aeruginosa alkane hydroxylases are preferentially induced at different points of the growth phase. PalkB2 is strongly induced at the start of the exponential phase of growth, while promoter PalkB1 is not, although both promoters are active during the late exponential phase and are switched off when the cells enter the stationary phase.

It is not self-evident what would be the advantage, if any, of the differential expression of alkB1 and alkB2. Both genes allowed growth at the expense of C12 to C16 alkanes when individually introduced into a Pseudomonas fluorescens derivative in which the equivalent native alkane hydroxylase had been inactivated (22). On the other hand, the membrane component of the alkane hydroxylase is detrimental to cell growth when expressed at high levels (4). The fact that both genes are silenced when growth ceases at stationary phase even if alkanes are still present in the medium agrees with this observation. It may therefore be advantageous to have two alkane hydroxylases, one of which is induced more efficiently when cells grow fast (AlkB2), and the other being induced to lower levels when cells grow slowly (AlkB1). Alternatively, AlkB1 may have a higher affinity for oxygen than AlkB2, which could explain why alkB1 is preferentially expressed at high cell densities, when the oxygen supply is limiting.

Induction of promoter PalkB1 can occur in the absence of RpoS, LasR, RhlR, and RelA.

Many P. aeruginosa genes that are activated at high cell densities or during the transition from the exponential to the stationary phase of growth are under control of the stationary-phase sigma factor RpoS (9), of the LasR/RhlR quorum-sensing response (5), or of the RelA-mediated stringent response (33). We investigated whether promoter PalkB1 could be controlled by any of these global regulatory mechanisms. All of them have been studied mainly in P. aeruginosa strain PAO1, for which several mutant derivatives are available.

Transcription of the alkB1 gene in P. aeruginosa PAO1 started at the same position as in strain RR1 and followed a similar expression pattern (not shown). Inactivation of the rpoS gene (strain PAOS [9]), the lasR gene (strain PAOR [11]), the rhlR gene (strain PT462 [10]), or the relA gene (strain PAΩR3 [33]) did not impair expression of promoter PalkB1 (not shown). Therefore, these global regulators are not needed for the expression of promoter PalkB1 during the late exponential phase. It is unclear what regulates the activity of this promoter. The P. aeruginosa genome may contain up to 24 sigma factors, many of which correspond to the subfamily of the extracytoplasmic function sigma factors (14, 28). The role and regulation of most of them are not known. However, known extracytoplasmic function sigma factors coordinate transcription in response to extracytoplasmic stimuli such as environmental signals. Expression of alkB1 could perhaps depend directly or indirectly on one of these uncharacterized sigma factors. It should be noted that the transcriptional regulators of the alkB1 and alkB2 genes have not been identified yet, and their expression could also be regulated.

Promoters PalkB1 and PalkB2 are subject to strong catabolic repression.

As shown in Fig. 1B, induction of promoters PalkB1 and PalkB2 by alkanes was severely inhibited when citrate was present in the growth medium and when cells were grown in a rich medium, suggesting that their expression is controlled by catabolic repression. The effect of other carbon sources was analyzed with strains containing the transcriptional fusions to the PalkB1 and PalkB2 promoters. β-Galactosidase levels were determined in late-exponential-phase cultures (A550 of 1.5 to 2), when both promoters were active. Glucose, citrate, lactate, succinate, glycerol, and myristic acid repressed PalkB1 activity 15- to 20-fold. Repression was higher for PalkB2 (20- to 40-fold). A similar effect occurred in LB medium containing tetradecane. Catabolic repression is a common phenomenon in alkane degradation pathways (3, 13, 26, 35), which indicates that they are not preferred growth substrates for bacteria.

Range of alkanes inducing promoters PalkB1 and PalkB2.

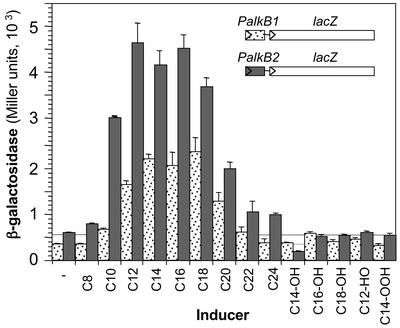

Reporter strains RR1B1 and RR1B2 were used to analyze the range of inducers of PalkB1 and PalkB2. To obtain comparable growth rates without interference from the different compounds tested as inducers, cells were grown in a minimal salts medium containing 0.3% (vol/vol) Tween 80 as the carbon source in addition to the inducer. At this concentration, Tween 80 does not generate catabolic repression but allows good growth. Promoters PalkB1 and PalkB2 showed similar behavior. In both cases, the highest induction was observed for C12 to C18 alkanes (Fig. 3). Promoter activity decreased almost twofold when C20 was used as the inducer and further diminished for alkanes of longer chain length. Although Tween 80 is a nonionic surfactant that probably facilitates alkane dispersion in the aqueous phase, the low induction achieved by the longer-chain alkanes could be related to their low water solubility. When alkanes were supplied dissolved in dioctylphthalate, induction increased by about twofold for C20, C22, and C24 but not for C18 or smaller alkanes. Octane was a very poor inducer for both promoters. Decane efficiently induced PalkB2 but was less effective for PalkB1. Alcanols, which are the products of alkane oxidation by alkane hydroxylase, did not serve as inducers. Aldehydes such as dodecanal and fatty acids such as myristic acid did not serve as inducers either. It is likely, therefore, that alkanes are the direct inducers of the alkB genes. The ability of alkane oxidation products to induce expression of alkane hydroxylases varies in different bacterial species. In P. putida GPo1, alkanes and alkanols are good inducers, while alcanals induce poorly and fatty acids induce not at all (7). In Burkholderia cepacia RR10, the alkane hydroxylase is induced both by alkanes and by their oxidation products (13), while in Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1, only the nonoxidized alkane can act as an inducer (19).

FIG. 3.

Inducers of alkB1 and alkB2 genes. Strains RR1B1 and RR1B2 were grown in minimal salts M9 medium containing Tween 80 (0.3%, vol/vol) as the carbon source in the absence or presence of different alkanes (C8 to C24), alcohols (C14-OH, C16-OH, and C18-OH), aldehydes (dodecanal, C12-HO), and fatty acids (myristic acid, C14-OOH). When cultures reached a turbidity of 2.0 (late exponential phase), the levels of β-galactosidase were measured. Liquid hydrocarbons were added at 1% (vol/vol), and solid hydrocarbons were added at 1% (wt/vol). Dotted bars correspond to the values obtained for strain RR1B1 (PalkB1::lacZ transcriptional fusion), and gray bars correspond to those for RR1B2 (PalkB2::lacZ transcriptional fusion).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to C. van Delden, A. Filloux, P. Greenberg, and T. Köhler for providing P. aeruginosa strains.

This work was supported by grants BIO2000-0939 from the Comisión Interministerial de Ciencia y Tecnología, CAM 07 M/0120/2000 from the Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid, and QLK2-CT-2001-01339 from the EU. M.M. was the recipient of a predoctoral fellowship from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Technology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alonso, A., F. Rojo, and J. L. Martinez. 1999. Environmental and clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa show pathogenic and biodegradative properties irrespective of their origin. Environ. Microbiol. 1:421-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauchop, T., and S. R. Eldsen. 1960. The growth of microorganisms in relation to their energy supply. J. Gen. Microbiol. 23:457-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canosa, I., J. M. Sánchez-Romero, L. Yuste, and F. Rojo. 2000. A positive feedback mechanism controls expression of AlkS, the transcriptional regulator of the Pseudomonas oleovorans alkane degradation pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 35:791-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, Q., D. B. Janssen, and B. Witholt. 1996. Physiological changes and alk gene instability in Pseudomonas oleovorans during induction and expression of alk genes. J. Bacteriol. 178:5508-5512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Kievit, T. R., and B. H. Iglewski. 2000. Bacterial quorum sensing in pathogenic relationships. Infect. Immun. 68:4839-4849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Lorenzo, V., M. Herrero, U. Jakubzik, and K. N. Timmis. 1990. Mini-Tn5 transposon derivatives for insertion mutagenesis, promoter probing, and chromosomal insertion of cloned DNA in gram-negative eubacteria. J. Bacteriol. 172:6568-6572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grund, A., J. Shapiro, M. Fennewald, P. Bacha, J. Leahy, K. Markbreiter, M. Nieder, and M. Toepfer. 1975. Regulation of alkane oxidation in Pseudomonas putida. J. Bacteriol. 123:546-556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Irani, V. R., and J. J. Rowe. 1997. Enhancement of transformation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 by Mg2+ and heat. BioTechniques 22:54-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jøorgensen, F., M. Bally, V. Chapon-Herve, G. Michel, A. Lazdunski, P. Williams, and G. S. Stewart. 1999. RpoS-dependent stress tolerance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 145:835-844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kohler, T., L. K. Curty, F. Barja, C. van Delden, and J. C. Pechere. 2000. Swarming of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is dependent on cell-to-cell signaling and requires flagella and pili. J. Bacteriol. 182:5990-5996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Latifi, A., M. Foglino, K. Tanaka, P. Williams, and A. Lazdunski. 1996. A hierarchical quorum-sensing cascade in Pseudomonas aeruginosa links the transcriptional activators LasR and RhIR (VsmR) to expression of the stationary-phase sigma factor RpoS. Mol. Microbiol. 21:1137-1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maeng, J. H., Y. Sakai, T. Ishige, Y. Tani, and N. Kato. 1996. Diversity of dioxygenases that catalyze the first step of oxidation of long-chain n-alkanes in Acinetobacter sp. strain M-1. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 141:177-182. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marín, M. M., T. H. Smits, J. B. van Beilen, and F. Rojo. 2001. The alkane hydroxylase gene of Burkholderia cepacia RR10 is under catabolite repression control. J. Bacteriol. 183:4202-4209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martínez-Bueno, M. A., R. Tobes, M. Rey, and J. L. Ramos. 2002. Detection of multiple extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors in the genome of Pseudomonas putida KT2440 and their counterparts in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Environ. Microbiol. 4:842-855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 16.Ostroff, R. M., B. Wretlind, and M. L. Vasil. 1989. Mutations in the hemolytic-phospholipase C operon result in decreased virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 grown under phosphate-limiting conditions. Infect. Immun. 57:1369-1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quinn, J. P. 1998. Clinical problems posed by multiresistant nonfermenting gram-negative pathogens. Clin. Infect. Dis. 27(Suppl. 1):S117-S124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ratajczak, A., W. Geissdorfer, and W. Hillen. 1998. Alkane hydroxylase from Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 is encoded by alkM and belongs to a new family of bacterial integral-membrane hydrocarbon hydroxylases. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:1175-1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ratajczak, A., W. Geissdorfer, and W. Hillen. 1998. Expression of alkane hydroxylase from Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 is induced by a broad range of n-alkanes and requires the transcriptional activator AlkR. J. Bacteriol. 180:5822-5827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rehm, H. J., and I. Reiff. 1981. Mechanisms and occurrence of microbial oxidation of long-chain alkanes. Adv. Biochem. Eng. 19:175-215. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 22.Smits, T. H. 2001. Cloning and functional analysis of bacterial genes involved in alkane oxidation. Ph.D. thesis. Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland.

- 23.Smits, T. H., S. B. Balada, B. Witholt, and J. B. van Beilen. 2002. Functional analysis of alkane hydroxylases from gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 184:1733-1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smits, T. H. M., M. Röthlisberger, B. Witholt, and J. B. van Beilen. 1999. Molecular screening for alkane hydroxylase genes in Gram-negative and Gram-positive strains. Environ. Microbiol. 1:307-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spiers, A. J., A. Buckling, and P. B. Rainey. 2000. The causes of Pseudomonas diversity. Microbiology 146:2345-2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Staijen, I. E., R. Marcionelli, and B. Witholt. 1999. The PalkBFGHJKL promoter is under carbon catabolite repression control in Pseudomonas oleovorans but not in Escherichia coli alk+ recombinants. J. Bacteriol. 181:1610-1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Staijen, I. E., J. B. Van Beilen, and B. Witholt. 2000. Expression, stability and performance of the three-component alkane mono-oxygenase of Pseudomonas oleovorans in Escherichia coli. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:1957-1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stover, C. K., X. Q. Pham, A. L. Erwin, S. D. Mizoguchi, P. Warrener, M. J. Hickey, F. S. Brinkman, W. O. Hufnagle, D. J. Kowalik, M. Lagrou, R. L. Garber, L. Goltry, E. Tolentino, S. Westbrock-Wadman, Y. Yuan, L. L. Brody, S. N. Coulter, K. R. Folger, A. Kas, K. Larbig, R. Lim, K. Smith, D. Spencer, G. K. Wong, Z. Wu, and I. T. Paulsen. 2000. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 406:959-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tani, A., T. Ishige, Y. Sakai, and N. Kato. 2001. Gene structures and regulation of the alkane hydroxylase complex in Acinetobacter sp. strain M-1. J. Bacteriol. 183:1819-1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Beilen, J. B., M. Neuenschwander, T. H. Smits, C. Roth, S. B. Balada, and B. Witholt. 2002. Rubredoxins involved in alkane oxidation. J. Bacteriol. 184:1722-1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Beilen, J. B., L. Veenhoff, and B. Witholt. 1998. Alkane hydroxylase systems in Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains able to grow on n-octane, p. 211-215. In K. Kieslich, C. P. van der Beek, J. A. M. de Bont, and W. J. J. van den Tweel (ed.), New frontiers in screening for microbial biocatalysts. Elsevier Science B.V., Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 32.van Beilen, J. B., M. G. Wubbolts, and B. Witholt. 1994. Genetics of alkane oxidation by Pseudomonas oleovorans. Biodegradation 5:161-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Delden, C., R. Comte, and A. M. Bally. 2001. Stringent response activates quorum sensing and modulates cell density-dependent gene expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 183:5376-5384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whyte, L. G., T. H. Smits, D. Labbe, B. Witholt, C. W. Greer, and J. B. Van Beilen. 2002. Gene cloning and characterization of multiple alkane hydroxylase systems in Rhodococcus strains Q15 and NRRL B-16531. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:5933-5942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yuste, L., I. Canosa, and F. Rojo. 1998. Carbon source-dependent expression of the PalkB promoter from the Pseudomonas oleovorans alkane degradation pathway. J. Bacteriol. 180:5218-5226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yuste, L., M. E. Corbella, M. J. Turiegano, U. Karlson, A. Puyet, and F. Rojo. 2000. Characterization of bacterial strains able to grow on high molecular mass residues from crude oil processing. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 32:69-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yuste, L., and F. Rojo. 2001. Role of the crc gene in catabolic repression of the Pseudomonas putida GPo1 alkane degradation pathway. J. Bacteriol. 183:6197-6206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]