Abstract

Enhancement of the production of soluble recombinant penicillin acylase in Escherichia coli via coexpression of a periplasmic protease/chaperone, DegP, was demonstrated. Coexpression of DegP resulted in a shift of in vivo penicillin acylase (PAC) synthesis flux from the nonproductive pathway to the productive one when pac was overexpressed. The number of inclusion bodies, which consist primarily of protein aggregates of PAC precursors in the periplasm, was highly reduced, and the specific PAC activity was highly increased. DegP was a heat shock protein induced in response to pac overexpression, suggesting that the protein could possibly suppress the physiological toxicity caused by pac overexpression. Coexpression of DegPS210A, a DegP mutant without protease activity but retaining chaperone activity, could not suppress the physiological toxicity, suggesting that DegP protease activity was primarily responsible for the suppression, possibly by degradation of abnormal proteins when pac was overexpressed. However, a shortage of periplasmic protease activity was not the only reason for the deterioration in culture performance upon pac overexpression because coexpression of a DegP-homologous periplasmic protease, DegQ or DegS, could not suppress the physiological toxicity. The chaperone activity of DegP is proposed to be another possible factor contributing to the suppression.

The well-known genetic information of Escherichia coli and successful applications of recombinant DNA technology make it possible for a variety of attempts with genetic engineering techniques to overproduce recombinant proteins. Upon performing the cultivation for recombinant protein production, there are two primary goals: high-cell-density cultivation and high-level gene expression. Culture performance can be optimized when the two goals are achieved simultaneously. High-cell-density culture can be obtained by fed-batch cultivation (48), in which concentrated medium is fed gradually into the bioreactor. The primary concern of this operation is developing an optimum feeding strategy, based on which cells can be maintained in a high-energy state for enhancing gene expression while cells are growing.

On the other hand, various genetic strategies have been developed for high-level gene expression (24). The use of strong promoters (e.g., tac, trc, and T7) for regulation of gene expression has been successfully applied to enhance recombinant protein production by improving transcriptional efficiency and perhaps translational efficiency as well (35). However, it is a common problem that insoluble protein aggregates, known as inclusion bodies, tend to accumulate inside the cells upon overproduction of gene products (14, 44). While the mechanism of inclusion body formation is not completely understood, it is believed that the overexpressed gene products cannot be suitably processed by folding modulators to develop a proper protein structure (46). For proteins destined to be exported, the protein formation mechanism would be more complicated, and the efficiency of translocation, posttranslocational folding, processing, and targeting becomes important. In principle, the precursors, intermediates, or final gene products can possibly form inclusion bodies in the cytoplasm and/or periplasm upon gene overexpression (4). This raises an important issue that, in addition to improving the efficiency of each gene expression step (i.e., transcription, translation, and posttranslational steps), balanced protein synthesis flux throughout these steps should be properly maintained to avoid the accumulation of any protein species upon the overproduction of recombinant proteins.

Within the past decade, the issues of protein misfolding in the bacterial periplasm and heat shock responses to extracytoplasmic stresses began to gain attentions. A specific periplasmic heat shock regulon of σE, which is similar to the σH heat shock regulon in the cytoplasm, has been identified in E. coli (9, 29, 32). Just as occurs in the cytoplasm, the heat shock responses to extracytoplasmic stresses were driven by synthesis of a variety of heat shock proteins expressing protease activity that degrades misfolded proteins and/or chaperone activity that renatures misfolded proteins. From the viewpoint of application, periplasmic proteins with these protease and/or chaperone activities would be proper candidates for relieving extracytoplasmic stresses when cells are overexpressing foreign gene products.

More than 10 periplasmic proteases have been identified in E. coli (25). On the other hand, several periplasmic proteins, including DegP (also known as HtrA or Do) (42), Skp (11), SurA (20), and FkpA (2), have been identified as having chaperone activity and could play a role in the folding or targeting of extracytoplasmic proteins. Among these periplasmic proteases and chaperones, DegP and FkpA are two gene products induced in response to extracytoplasmic stresses, such as heat shock or the presence of misfolded proteins, via the σE heat shock regulon and Cpx two-component systems (32).

DegP is perhaps the only periplasmic heat shock protein with both protease and chaperone activities. It has an inducible serine protease activity for breakdown of aberrant periplasmic proteins arising upon extracytoplasmic stresses (17, 45). Another uncommon feature of DegP is that this protein can exhibit either protease or chaperone activity with temperature as the regulatory switch (42). With these multiple functions, DegP is known to be involved in relieving extracytoplasmic stresses upon overexpression of several gene products, including alkaline phosphatase (PhoA) (13), DsbA′-PhoA (10), MalS (42), and maltose-binding protein (MalE) variants (3, 28).

We previously demonstrated that the presence of exogenous DegP could enhance the production of recombinant penicillin acylase (PAC), an important industrial enzyme for the production of many β-lactam antibiotics (37), in E. coli (21). The formation of mature PAC in the periplasm involves a series of posttranslational steps, including translocation and periplasmic processing/folding steps, which are unusual for prokaryotic proteins (Fig. 1) (38). The periplasmic processing mechanism is known to consist of various proteolytic steps via intramolecular autoproteolysis (15, 38). The formation of inclusion bodies, which are composed primarily of PAC precursors in the periplasm, was recently identified as an important obstacle to the overproduction of PAC in E. coli (8, 36, 43). Hence, efforts have been directed to reducing the number of periplasmic PAC inclusion bodies.

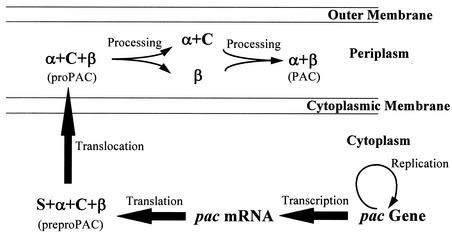

FIG. 1.

Synthesis and maturation of PAC in E. coli. The structural pac gene from E. coli ATCC 11105 encodes a 95-kDa polypeptide precursor (preproPAC) composed of, from the N terminus to the C terminus, a signal peptide (S), α subunit (α), connecting peptide (C), and β subunit (β). The signal peptide directs the export of preproPAC into the periplasm and is removed after translocation. Another type of PAC precursor, proPAC, 92 kDa, is formed in the periplasm. Periplasmic processing, which involves a series of proteolytic steps, follows to remove the connecting peptide, and the two subunits (α at 24 kDa and β at 62 kDa) become available for assembly of mature PAC.

In this study, we provide evidence that DegP functions primarily as a protease to improve cell physiology by preventing the misfolding and aggregation of periplasmic PAC precursors when pac is overexpressed. Cultivation performance for the production of recombinant PAC was significantly enhanced due to improved cell physiology as well as simultaneous increases in the pac gene expression level and culture cell density.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

Strains and plasmids used in the study are summarized in Table 1 and briefly described here. MDΔP7 was used as the host for the production of recombinant PAC. Compared to the parent strain, E. coli HB101, MDΔP7 could potentially have higher pac translational and periplasmic processing efficiency for pac expression (7). MC4100λφ[htrA-lacZ] contains a single copy of the PdegP::lacZ transcriptional fusion at the λ phage attachment site of the chromosome (12). Molecular cloning was performed according to standard protocols (34), and HB101 was the host for cloning. Restriction enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs (Beverly, Mass.). PCR was conducted in an automated thermal cycler (Amplitron II; Thermolyne, Dubuque, Iowa). Purification of plasmid DNA was performed with a spin column kit purchased from Clontech (Palo Alto, Calif.) or Viagen (Taipei, Taiwan). Plasmid transformation was carried out with an electroporator (E. coli Pulser; Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.).

TABLE 1.

Strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides

| Strain, plasmid, or oligonucleotide | Relevant genotype or phenotypea | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| HB101 | F−hsdS20 leuB6 recA13 ara-14 proA2 lacY1 thi-1 galK2 rpsL20 xyl-5 mtl-1 supE44 λ− | CCRCb (5) |

| MDΔP7 | Penicillin-sensitive and 6-APA-resistant mutant derived from HB101 | This lab (7) |

| MC4100λφ [htrA-lacZ] | MC4100 λ[PdegP::lacZ] | K. Makino (12) |

| Plasmid | ||

| pAR3 | A ParaB expression vector, ori pACYC184, Cmr | J. Gutierrez (31) |

| pARDegP | Expression vector containing degP fused with araB promoter, ori pACYC184, Cmr | This study |

| pARDegPS210A | Expression vector containing degPS210A fused with araB promoter, ori pACYC184, Cmr | This study |

| pARDegQ | Expression vector containing degQ fused with araB promoter, ori pACYC184, Cmr | This study |

| pARDegS | Expression vector containing degS fused with araB promoter, ori pACYC184, Cmr | This study |

| pKS12 | Expression vector containing degP gene, ori pACYC184, Cmr | J. Beckwith (45) |

| pTrcKn99A | Ptrc expression vector derived from pTrc99A, ori pBR322, Kmr | This lab (8) |

| pTrcKnPAC2902 | Expression vector containing pac operon fused with trc promoter, ori pBR322, Kmr | This lab (8) |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| PA and PB | 5′-AAATCCATGGCAAAAACCACATTAGCACTG-3′ and 5′-CGTAAGGTACCGCATTGTGCAA-3′; primer pair for amplification of degP | This study |

| PC and PD | 5′-GGAACCATGGCAAAACAAACCCAG-3′ and 5′-GAACGGCAGCAGGGTACCACG-3′; primer pair for amplification of degQ | This study |

| PE and PF | 5′-GCCTCCACCATGGTTGTGAAGCTCTTAC-3′ and 5′-AAATCTATCGGTACCCTGAGCGCA-3′; primer pair for amplification of degS | This study |

| PSA and APSA | 5′-CCGTGGTAACGCCGGTGGCGCCCTGGTTAAC-3′ and 5′-GTTAACCAGGGCGCCACCGGCGTTACCACGG-3′; primer pair for site-directed mutagenesis of degP | This study |

Designed restriction sites are underlined and introduced mutations are in italics. 6-APA, 6-aminopenicillanic acid.

Culture Collection & Research Center, Taiwan, ROC.

E. coli genes degP, degQ, and degS were amplified by PCR with PFU DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) and appropriate primers (Table 1). The PCR templates were pKS12 (45) for degP and HB101 genomic DNA for degQ and degS. The PCR products flanked with NcoI and KpnI sites (1.55, 1.44, and 1.24 kb for degP, degQ, and degS, respectively) were purified and cloned into the corresponding restriction sites of pTrcKn99A. DNA sequencing of the PCR-cloned genes was performed with pTrcKn99A-derived vectors. The NcoI-KpnI DNA fragments containing degP, degQ, and degS were subcloned into the NcoI-KpnI backbone of pAR3, which had been treated by complete KpnI digestion and partial NcoI digestion, to form pARDegP, pARDegQ, and pARDegS, respectively. The design of the NcoI site in the sense primers resulted in changes in the second amino acid of the signal peptides of Lys→Ala for DegP and DegQ and Phe→Val for DegS, and these mutations did not appear to affect translocation.

In vitro site-directed mutagenesis was conducted with the QuickChange kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. pARDegP was the mutagenesis template, and PSA/APSA were the mutagenesis primers; they contain a silent mutation with an extra NarI site for screening purposes. pTrcKnPAC2902 contains the pac operon, whose transcription is regulated by the trc promoter (8). It has the pBR322 replication origin and is therefore compatible with various pAR3-derived plasmids carrying the pACYC184 replication origin.

Cultivation.

Cells were revived by streaking the stock culture stored at −80°C on a Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plate (5 g of NaCl, 5 g of Bacto yeast extract, 10 g of Bacto tryptone, and 15 g of Bacto agar per liter). The plate was incubated at 37°C for approximately 20 h. An isolated single colony was picked to inoculate 25 ml of LB medium, which was then incubated at 37°C on a rotary shaker at 220 rpm for approximately 15 h. The medium was supplemented with kanamycin at 25 μg/ml or chloramphenicol at 32 μg/ml when necessary. The seed culture at a volume of 10 ml was used to inoculate a table-top bioreactor (Omni-Culture; VirTis, Gardiner, N.Y.) containing 1 liter of working volume of LB medium. Unless otherwise specified, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and arabinose were added simultaneously to induce the synthesis of PAC and protease (DegP, DegQ, or DegS), respectively. The culture was supplemented with 10 μl of antifoam 289 per liter (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) to avoid excessive foaming. Filter-sterilized air at 1.5 liters/min was purged into the culture for aeration. The culture pH was held at 7.0 ± 0.1 by adding 3 N NaOH or 3 N HCl with a combined pH electrode (Mettler-Toledo, Berne, Switzerland), a pH controller (PC310; Suntex, Taipei, Taiwan), and two peristaltic pumps (101U/R; Watson Marlow, Falmouth, United Kingdom). The bioreactor was operated at 28°C and 500 rpm for approximately 50 h.

Analytical methods.

The culture sample was appropriately diluted with saline solution for measuring cell density as the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) with a spectrophotometer (V-530; Jasco, Tokyo, Japan). For the preparation of cell extract, 40 OD600 units of cells were centrifuged at 2°C and 6,000 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was assayed for the extracellular enzyme activity. The cell pellet was resuspended in 2 ml of sodium phosphate buffer (0.05 M, pH 7.5). The cell suspension was sonicated for 2 min with an ultrasonic processor (Sonics & Materials, Danbury, Conn.) and then centrifuged at 2°C and 20,000 × g for 20 min. The supernatant containing soluble proteins was assayed for the intracellular enzyme activity. The pellet containing insoluble proteins and cell debris was washed with phosphate buffer, resuspended in TE-SDS buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]) and heated at 100°C for 5 min. The protein content of the pellet was analyzed as the insoluble fraction. All the analytical methods in this study, including microbiological screening of PAC-producing strains, PAC assay, SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and immunological analysis (Western blotting), were performed as described previously (8). β-Galactosidase was assayed as described previously (26). All assays were conducted in duplicate.

RESULTS

Effect of DegP coexpression on pac overexpression.

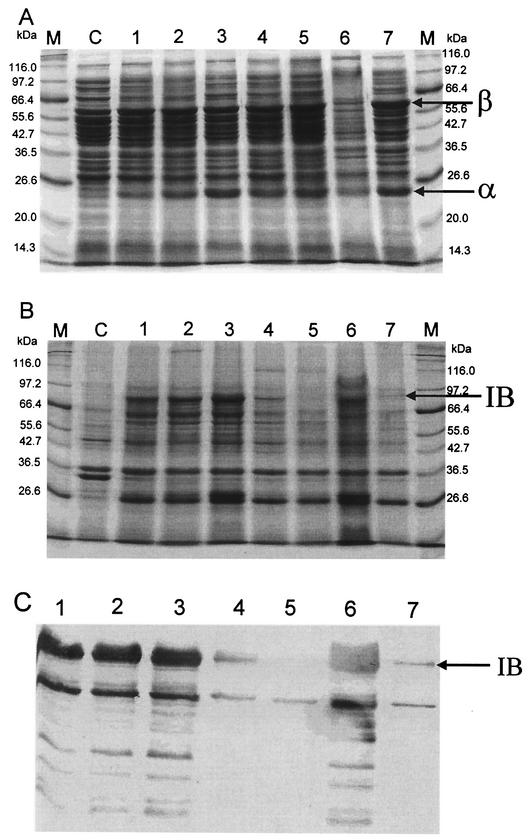

For the control experiments with MDΔP7 harboring pTrcKnPAC2902 and MDΔP7 harboring pTrcKnPAC2902 and pAR3, the culture performance in pac overexpression is summarized in Fig. 2. In all cases, formation of inclusion bodies was observed (Fig. 3), though the production of PAC was effective. The inclusion bodies were primarily composed of proPAC in the periplasm, as described in previous reports (6, 36, 43). The presence of exogenous DegP resulted in a significant decrease in the number of PAC inclusion bodies and increase in the specific PAC activity when pac was overexpressed. For the culture of MDΔP7 harboring pTrcKnPAC2902 and pARDegP with IPTG induction at 0.05 mM but without arabinose induction, formation of PAC inclusion bodies was still observed, but there were significantly fewer than in the control experiments with the same induction conditions (Fig. 3). The reduction in the number of PAC inclusion bodies resulted from leaky expression of degP by pARDegP, suggesting that a relatively small amount of exogenous DegP would be enough to improve the misfolding of proPAC. The inclusion bodies completely disappeared upon increasing the intracellular DegP concentration for the culture of MDΔP7 harboring pTrcKnPAC2902 and pARDegP with simultaneous IPTG induction at 0.05 mM and arabinose induction at 0.05 g/liter (Fig. 3).

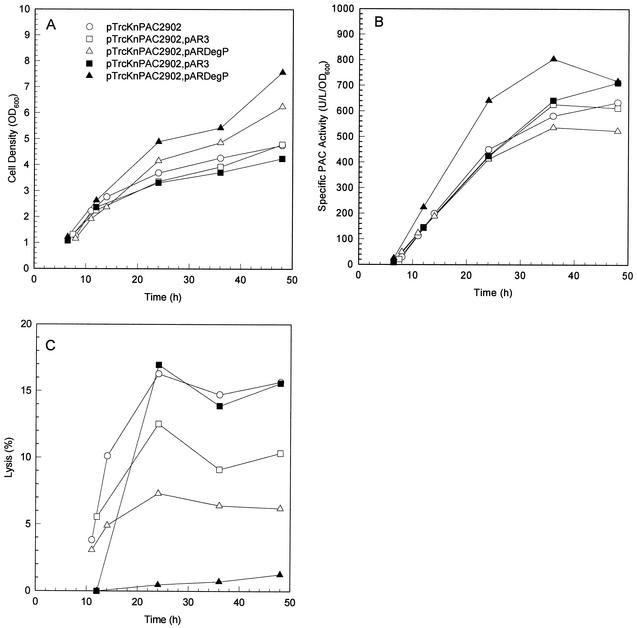

FIG. 2.

Effect of DegP on pac overexpression: Time profiles of cell density (panel A), specific PAC activity (panel B), and cell lysis level (panel C) for cultures of MDΔP7 harboring various plasmids are shown. The level of cell lysis was defined as the percentage of total PAC activity detected in the extracellular medium. All cultures were supplemented with 0.05 mM IPTG for induction of PAC synthesis when the first sample was taken (i.e., OD600 of 1.0 to 1.3). Open symbols represent cultures without arabinose supplementation, whereas solid symbols represent those with arabinose supplementation (0.05 g/liter) for induction of DegP synthesis when the first sample was taken.

FIG. 3.

SDS-PAGE (panels A and B) and immunological (panel C) analyses of protein contents of soluble (panel A) and insoluble (panels B and C) fractions of the last samples of various cultures shown in Fig. 2 and 4. Lanes: M, protein markers; C, pTrcKnPAC2902 without IPTG as the control experiment; 1, pTrcKnPAC2902 with 0.05 mM IPTG; 2, pTrcKnPAC2902 and pAR3 with 0.05 mM IPTG; 3, pTrcKnPAC2902 and pAR3 with 0.05 mM IPTG and 0.05 g of arabinose per liter; 4, pTrcKnPAC2902 and pARDegP with 0.05 mM IPTG only; 5, pTrcKnPAC2902 and pARDegP with 0.05 mM IPTG and 0.05 g of arabinose per liter; 6, pTrcKnPAC2902 and pARDegP with 0.1 mM IPTG only; 7, pTrcKnPAC2902 and pARDegP with 0.1 mM IPTG and 0.05 g of arabinose per liter.

Cell physiology was significantly improved when degP was coexpressed. Up to 16% of PAC activity was detected in the extracellular medium for the control experiment, versus only 1% for the culture of MDΔP7 harboring pTrcKnPAC2902 and pARDegP with simultaneous IPTG induction at 0.05 mM and arabinose induction at 0.05 g/liter, suggesting that a much smaller number of cells were lysed when degP was coexpressed. As a result, culture performance was significantly improved (Fig. 2). Compared to the control culture of MDΔP7 harboring pTrcKnPAC2902, the final cell density and specific PAC activity were increased by 58% (7.6 versus 4.8 OD600 units) and 13% (717 versus 634 U/liter/OD600 units), respectively, resulting in an 80% increase in the volumetric PAC activity (5,424 versus 3,011 U/liter). An increase in arabinose induction concentration to 0.1 g/liter did not further improve culture performance (data not shown).

More distinct DegP effect upon extremely high level pac expression.

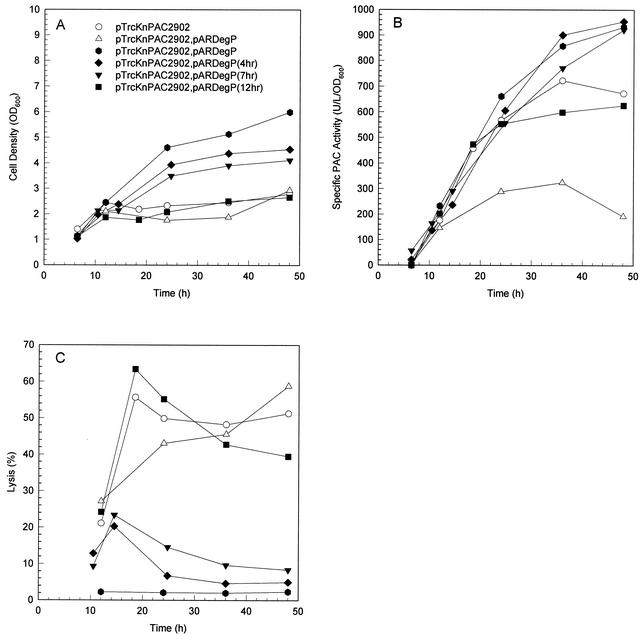

The positive effect of DegP on the production of PAC was even more distinct when pac was overexpressed with a higher IPTG concentration for induction of 0.1 mM (Fig. 4). With these culture conditions, the number of PAC inclusion bodies was extremely large for the control experiment with MDΔP7 harboring pTrcKnPAC2902 (Fig. 3). The amount of leaky degP expression for MDΔP7 harboring pTrcKnPAC2902 and pARDegP was not enough for proper function when arabinose was not added. Cell growth was significantly inhibited due to the extracytoplasmic stress. Increasing the intracellular DegP concentration by adding 0.05 g of arabinose per liter resulted in a significant decrease in the number of PAC inclusion bodies (Fig. 3). Coexpression of degP could also improve cell physiology by reducing the level of cell lysis, relieving the inhibition of cell growth. Compared to the control culture of MDΔP7 harboring pTrcKnPAC2902, the final cell density and specific PAC activity were increased by 114% (6.0 versus 2.8 OD600 units) and 39% (933 versus 673 U/liter/OD600 unit), respectively, resulting in an approximately twofold increase in the volumetric PAC activity (5,593 versus 1,880 U/liter). Up to 50% of PAC activity was detected in the extracellular medium for the control experiment, whereas only 2% was found for the culture of MDΔP7 harboring pTrcKnPAC2902 and pARDegP with simultaneous IPTG induction at 0.1 mM and arabinose induction at 0.05 g/liter.

FIG. 4.

Effect of DegP on pac overexpression. Same as Fig. 2 except all the cultures were supplemented with 0.1 mM IPTG. Solid rhombus, triangle, and square represent cultures supplemented with 0.1 mM IPTG when the first sample was taken but with 0.05 g of arabinose per liter added 4 h, 7 h, and 12 h, respectively, after the first sample was taken.

The effect of degP induction timing was investigated by cultivations in which degP coexpression was induced 4 h, 7 h, and 12 h after pac induction (Fig. 4). It appears that the positive effects (i.e., enhanced cell growth, increased pac expression, and reduced cell lysis) on pac overexpression were not observed until degP coexpression. In addition, these effects gradually diminished when degP coexpression was delayed and could hardly be observed if degP coexpression was delayed by 12 h (Fig. 4). The results suggest that cell physiology improved immediately after degP coexpression and that the timing of degP coexpression was rather critical. The PAC inclusion bodies formed before degP coexpression disappeared gradually toward the end of the cultivations (data not shown). The results suggest that DegP not only prevented further formation of PAC inclusion bodies but also degraded the misfolded proPAC. However, the question of whether the misfolded proPAC was simply degraded or was rescued and subsequently shifted into the productive pathway remains to be answered.

DegP is a heat shock protein induced in response to pac overexpression.

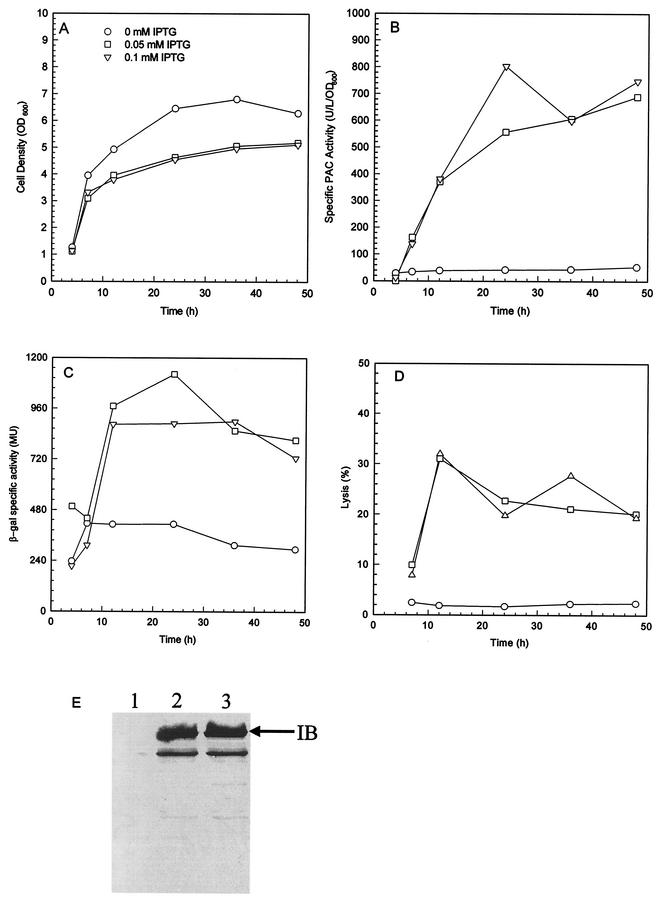

MC4100λφ[htrA-lacZ] contains a single copy of the PdegP::lacZ transcriptional fusion at the λ phage attachment site of the chromosome of MC4100 (12). The strain can be used to estimate the level of the cell's heat shock response to extracytoplasmic stresses by assaying β-galactosidase activity. With MC4100λφ[htrA-lacZ] harboring pTrcKnPAC2902, an increase in degP promoter activity was observed as a physiological response to pac overexpression, which resulted in slight growth inhibition but significant increases in specific PAC activity, the number of PAC inclusion bodies, and the level of cell lysis (Fig. 5). The results suggest that DegP is a heat shock protein induced in response to pac overexpression.

FIG.5.

Heat shock response to pac overexpression. Time profiles of cell density (panel A), specific PAC activity (panel B), specific β-galactosidase activity (panel C), and cell lysis level (panel D) for cultures of MC4100λφ[htrA-lacZ] harboring pTrcKnPAC2902 induced with IPTG at 0, 0.05, and 0.1 mM are shown. Immunological analysis of the protein contents of the insoluble fractions of the last samples of various cultures is shown in panel E. Lane 1, no IPTG; 2, 0.05 mM IPTG; 3, 0.1 mM IPTG.

Effect of coexpression of DegPS210A and other DegP-like periplasmic proteases on pac overexpression.

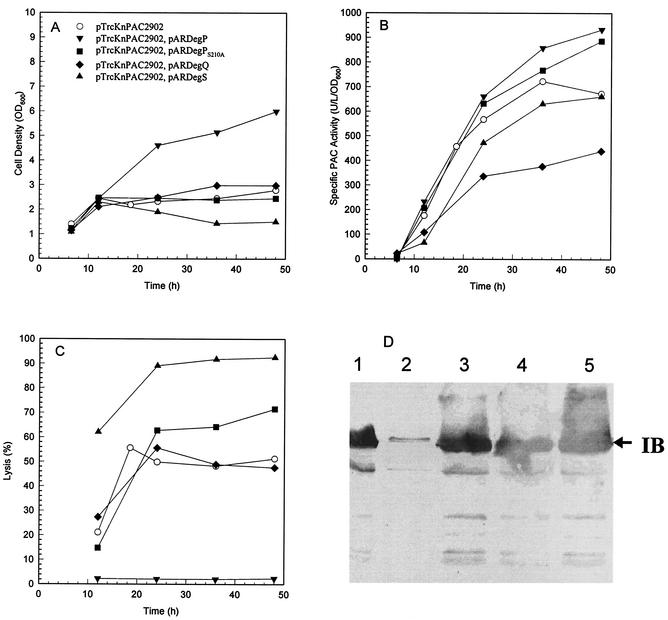

The role that DegP plays in pac overexpression can be identified by comparing culture performance among MDΔP7 harboring pTrcKnPAC2902, MDΔP7 harboring pTrcKnPAC2902 and pARDegP, and MDΔP7 harboring pTrcKnPAC2902 and pARDegPS210A. The results are summarized in Fig. 6. Unlike wild-type DegP, DegPS210A could not suppress the physiological toxicity caused by pac overexpression. Culture performance (i.e., pac expression level, number of PAC inclusion bodies, cell growth, and cell lysis) of MDΔP7 harboring pTrcKnPAC2902 and pARDegPS210A was similar to that of the control experiment with MDΔP7 harboring pTrcKnPAC2902. The results suggest that the protease activity of DegP is responsible for suppression of the physiological toxicity caused by pac overexpression (see later discussion).

FIG. 6.

Effect of various periplasmic proteases on pac overexpression. Same as Fig. 2 except the solid symbols represent cultures further supplemented with 0.05 g of arabinose per liter for induction of protease synthesis when the first sample was taken. Immunological analysis of the protein contents of the insoluble fractions of the last samples of various cultures is shown in panel D. Lanes: 1, pTrcKnPAC2902; 2, pTrcKnPAC2902 and pARDegP; 3, pTrcKnPAC2902 and pARDegPS210A; 4, pTrcKnPAC2902 and pARDegQ; 5, pTrcKnPAC2902 and pARDegS.

Since the protease activity of DegP was primarily responsible for suppression of the physiological toxicity caused by pac overexpression, it would be interesting to see if any other periplasmic protease had the same phenotype. The effect of DegQ and DegS, two periplasmic serine proteases homologous to DegP, on pac overexpression was investigated with MDΔP7 harboring pTrcKnPAC2902 and pARDegQ or pARDegS, and the results are summarized in Fig. 6. Culture performance of MDΔP7 harboring pTrcKnPAC2902 and pARDegQ and of MDΔP7 harboring pTrcKnPAC2902 and pARDegS was similar to or even worse than that in the control experiment with MDΔP7 harboring pTrcKnPAC2902. The results suggest that neither DegQ nor DegS could suppress the physiological toxicity caused by pac overexpression.

DISCUSSION

Coexpression of DegP resulted in the following improvements upon pac overexpression: (i) it prevented misfolding of proPAC due to a reduction in the number of PAC inclusion bodies; (ii) it shifted PAC synthesis flux from the nonproductive pathway to the productive one due to an increase in pac expression level; and (iii) it improved cell physiology due to enhanced cell growth and less cell lysis (Fig. 2, 3, and 4). The result that DegP is a heat shock protein induced in response to pac overexpression (Fig. 5) suggests that DegP could suppress the physiological toxicity caused by pac overexpression. DegP was also found to be a heat shock protein induced in response to the misfolding of many periplasmic proteins, such as PhoA (13), DsbA′-PhoA (10), MalS (42), OmpF mutants (27), and maltose-binding protein (MalE) variants (3, 28). Misfolding of these proteins is usually the consequence of overexpression of gene products or a folding defect caused by certain mutations. While the heat shock response was initiated primarily for degrading or renaturing misfolded proteins in the periplasm, the increased DegP level might not be high enough for complete function and the misfolded gene products still accumulated as periplasmic inclusion bodies (10, 13, 28). Normally, heat shock proteins express the protease activity for degrading misfolded proteins and/or chaperone activity for renaturing misfolded proteins. We therefore tried to identify the exact role(s) that DegP plays as a heat shock protein in response to pac overexpression.

There are at least two hypothetical conditions which are not completely mutually exclusive to explain the positive effect of DegP when pac was overexpressed. First, the periplasmic processing machinery was saturated with PAC precursors of proPAC transiently formed in an excess amount. The periplasmic processing of proPAC is initiated by proteolysis on the Thr263-Ser264 bond via intramolecular autoproteolysis (15). Two protein chains (i.e., α plus C and β in Fig. 1) are formed and fold with each other. Enzyme activity at approximately the same level as that of mature PAC could be detected for the folding complex (22, 23). Apparently, the production of PAC was limited by the initiation step, as proPAC was the major aggregation species upon pac overexpression. In other words, folding of proPAC in the periplasm was not properly carried out for subsequent autoproteolysis, possibly due to an increased level of the local protein concentration. This limitation possibly can be resolved by periplasmic chaperones. Second, cell physiology was significantly affected as a result of extracytoplasmic stresses, such as protein misfolding and/or failure of degradation of misfolded proteins in the periplasm upon pac overexpression. This limitation possibly can be resolved by periplasmic proteases and/or chaperones.

DegP has both protease and chaperone activities (42), by which cell physiology can be improved. For example, DegP was identified as a periplasmic heat shock protein for degrading abnormal proteins in the periplasm when phoA was overexpressed (13). Overexpression of phoA in a degP mutant caused a severe defect in export of several proteins, including PhoA itself, and such a defect was not observed (even in the degP mutant) in the absence of phoA overexpression (13). The proteolytic activity of DegP could also suppress the physiological toxicity originating from overexpression of a hybrid protein of DsbA′-PhoA in a similar way (10). As a result, DegP was identified as a peripheral membrane protease which degrades misfolded proteins accumulated near the periplasmic side upon extracytoplasmic stresses (13, 30, 40). On the other hand, DegP was also a heat shock protein in response to the misfolding of ovexpressed MalS in the periplasm and the physiological role was, however, proposed to be a chaperone (42). While MalS solubility was improved, the number of MalS inclusion bodies was not reduced, and the in vivo chaperone activity of DegP was not clearly demonstrated (42). It would be interesting to see which activity contributed the improvement documented in Fig. 2 to 4 when pac was overexpressed.

DegP is a serine protease whose active center consists of the catalytic triad residues His105, Asp135, and Ser210 (33). The DegP variant harboring the S210A mutation completely lost the protease activity but retained the chaperone activity (41, 42), as the mutation induced minor changes in the tertiary structure of the protein (39). Hence, the role of DegP in pac overexpression can be identified with this mutant, DegPS210A, being coexpressed. Unlike wild-type DegP, DegPS210A could not suppress the physiological toxicity caused by pac overexpression (Fig. 6), suggesting that DegP functioned as a protease to improve culture performance upon pac overexpression. Similar approaches were conducted to identify the protease activity of DegP for suppression of the physiological toxicity when the hybrid protein DsbA′-PhoA was overexpressed (10) or the chaperone activity of DegP for suppression of heat shock responses originating from misfolding of MalS (42) and OmpF mutants (27).

More than 10 periplasmic proteases have been identified in E. coli. Among them, DegQ and DegS are the two with DegP-like protein function and structure. All three proteins are serine proteases (47). However, only DegP is heat inducible and only E. coli degP mutants have a temperature-sensitive phenotype (47). DegQ can functionally substitute for DegP under certain conditions (47). Though DegQ is not a heat shock protein, it can transiently degrade denatured, unfolded proteins which accumulate in the periplasm upon heat shock or extracytoplasmic stresses and/or newly secreted proteins prior to folding and disulfide bond formation (17). Similar to many intracellular proteases, which form large oligomeric complexes, both DegP and DegQ form hexamers or dodecamers in solution (17, 18). DegP and DegQ are similar in size and highly homologous (47). In addition, they both contain two PDZ domains, which are responsible for substrate recognition, and possibly have a common substrate recognition mechanisms (30). On the other hand, DegS is also homologous to DegP, though the homology is not as strong as that of DegQ and DegP (47). It also has the PDZ domain for substrate recognition, but only one (30). The physiological function of DegS was identified to be related to the regulation of σE activity (1).

Unlike DegP, neither DegQ nor DegS could suppress the physiological toxicity caused by pac overexpression (Fig. 6). The apparent different effects of the two highly homologous proteases, DegP and DegQ, on pac overexpression suggest that the improvement in culture performance was not simply caused by DegP protease activity. In that case, the chaperone activity could be another possible improving factor. It is known that DegP can exhibit protease or chaperone activity with temperature as an environmental switch; namely the protease and chaperone activities dominate under high and low temperatures, respectively (42). Hence, the possibility that the positive effect of DegP on pac overexpression was caused by the chaperone activity should not be excluded since all the cultivations were conducted at a relatively low temperature of 28°C in this study. The chaperone activity was responsible for shifting the PAC synthesis flux from the nonproductive pathway to the productive one possibly by increasing the solubility of proPAC. In addition, increasing the efficiency of the current limiting step (i.e., autoproteolysis of proPAC) would require a proper folding status of proPAC that could possibly be achieved by DegP chaperone activity.

It should be noted that the chance that DegP protease activity directly assisted the periplasmic processing of proPAC, which consists of several proteolytic steps, would be slim due to the following reasons. First, DegP targets its protein substrates by recognizing a state of protein denaturation rather than specific amino acid sequences in particular proteins (19). The PDZ domains of DegP are responsible for substrate recognition (30). In addition, unfolding of the protein substrates would be essential for their access into the inner chamber of the double ring-shaped DegP, where cleavage of peptide bonds may occur (16). Second, both DegP and DegQ have two PDZ domains and an active center with the catalytic triad residues of His, Asp, and Ser for exhibiting protease activity. One would expect to see the same effect for DegQ as for DegP on pac overexpression if DegP protease activity directly assisted autoproteolysis of proPAC.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Science Council of Taiwan (grant no. NSC 91-2214-E-035-007).

We thank K. Makino, J. Gutierrez, and J. Beckwith for providing strains for this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alba, B. M., H. J. Zhong, J. C. Pelayo, and C. A. Gross. 2001. degS (hhoB) is an essential Escherichia coli gene whose indispensable function is to provide σE activity. Mol. Microbiol. 40:1323-1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arie, J. P., N. Sassoon, and J. M. Betton. 2001. Chaperone function of FkpA, a heat shock prolyl isomerase, in the periplasm of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 39:199-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Betton, J. M., D. Boscus, D. Missiakas, S. Raina, and M. Hofnung. 1996. Probing the structural role of an alpha beta loop of maltose-binding protein by mutagenesis: heat shock induction by loop variants of the maltose-binding protein that form periplasmic inclusion bodies. J. Mol. Biol. 262:140-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowden, G. A., A. M. Paredes, and G. Georgiou. 1991. Structure and morphology of protein inclusion bodies in Escherichia coli. Bio/Technology 9:725-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyer, H. W., and D. Roulland-Dussoix. 1969. A complementation analysis of the restriction and modification of DNA in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 41:459-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chou, C. P., J.-H. Tseng, B.-Y. Kuo, K.-M. Lai, M.-I. Lin, and H.-K. Lin. 1999. Effect of SecB chaperone on production of periplasmic penicillin acylase in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Prog. 15:439-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chou, C. P., C.-C. Yu, W.-J. Lin, B.-Y. Kuo, and W.-C. Wang. 1999. Novel strategy for efficient screening and construction of host/vector systems to overproduce penicillin acylase in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 65:219-226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chou, C. P., C.-C. Yu, J.-H. Tseng, M.-I. Lin, and H.-K. Lin. 1999. Genetic manipulation to identify limiting steps and develop strategies for high-level expression of penicillin acylase in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 63:263-272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Connolly, L., A. De Las Penas, B. M. Alba, and C. A. Gross. 1997. The response to extracytoplasmic stress in Escherichia coli is controlled by partially overlapping pathways. Genes Dev. 11:2012-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guigueno, A., P. Belin, and P. Boquet. 1997. Defective export in Escherichia coli caused by DsbA′-PhoA hybrid proteins whose DsbA′ domain cannot fold into a conformation resistant to periplasmic proteases. J. Bacteriol. 179:3260-3269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayhurst, A., and W. J. Harris. 1999. Escherichia coli Skp chaperone coexpression improves solubility and phage display of single-chain antibody fragments. Protein Express. Purif. 15:336-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hiratsu, K., M. Amemura, H. Nashimoto, H. Shinagawa, and K. Makino. 1995. The rpoE gene of Escherichia coli, which encodes σE, is essential for bacterial growth at high temperature. J. Bacteriol. 177:2918-2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kadokura, H., H. Kawasaki, K. Yoda, M. Yamasaki, and K. Kitamoto. 2001. Efficient export of alkaline phosphatase overexpressed from a multicopy plasmid requires degP, a gene encoding a periplasmic protease of Escherichia coli. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 47:133-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kane, J. F., and D. L. Hartley. 1988. Formation of recombinant protein inclusion bodies in Escherichia coli. Trends Biotechnol. 6:95-101. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kasche, V., K. Lummer, A. Nurk, E. Piotraschke, A. Rieks, S. Stoeva, and W. Voelter. 1999. Intramolecular autoproteolysis initiates the maturation of penicillin amidase from Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1433:76-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim, K. I., S. C. Park, S. H. Kang, G. W. Cheong, and C. H. Chung. 1999. Selective degradation of unfolded proteins by the self-compartmentalizing HtrA protease, a periplasmic heat shock protein in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 294:1363-1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kolmar, H., P. R. Waller, and R. T. Sauer. 1996. The DegP and DegQ periplasmic endoproteases of Escherichia coli: specificity for cleavage sites and substrate conformation. J. Bacteriol. 178:5925-5929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krojer, T., M. Garrido-Franco, R. Huber, M. Ehrmann, and T. Clausen. 2002. Crystal structure of DegP (HtrA) reveals a new protease-chaperone machine. Nature 416:455-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laskowska, E., D. Kuczynska-Wisnik, J. Skorko-Glonek, and A. Taylor. 1996. Degradation by proteases Lon, Clp and HtrA, of Escherichia coli proteins aggregated in vivo by heat shock; HtrA protease action in vivo and in vitro. Mol. Microbiol. 22:555-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lazar, S. W., and R. Kolter. 1996. SurA assists the folding of Escherichia coli outer membrane proteins. J. Bacteriol. 178:1770-1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin, W.-J., S.-W. Huang, and C. P. Chou. 2001. DegP coexpression minimizes inclusion body formation upon overproduction of recombinant penicillin acylase in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 73:484-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindsay, C. D., and R. H. Pain. 1990. The folding and solution conformation of penicillin G acylase. Eur. J. Biochem. 192:133-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lindsay, C. D., and R. H. Pain. 1991. Refolding and assembly of penicillin acylase, an enzyme composed of two polypeptide chains that result from proteolytic activation. Biochemistry USA 30:9034-9040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Makrides, S. C. 1996. Strategies for achieving high-level expression of genes in Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Rev. 60:512-538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller, C. G. 1996. Protein degradation and proteolytic modification, p. 938-954. In F. C. Neidhardt, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed., vol. 1. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 26.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 27.Misra, R., M. Castillokeller, and M. Deng. 2000. Overexpression of protease-deficient DegPS210A rescues the lethal phenotype of Escherichia coli OmpF assembly mutants in a degP background. J. Bacteriol. 182:4882-4888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Missiakas, D., J.-M. Betton, and S. Raina. 1996. New components of protein folding in extracytoplasmic compartments of Escherichia coli SurA, FkpA and Skp/OmpH. Mol. Microbiol. 21:871-884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Missiakas, D., and S. Raina. 1997. Protein misfolding in the cell envelope of Escherichia coli: new signaling pathways. Trends Biochem. Sci. 22:59-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pallen, M. J., and B. W. Wren. 1997. The HtrA family of serine proteases. Mol. Microbiol. 26:209-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perez-Perez, J., and J. Gutierrez. 1995. An arabinose-inducible expression vector, pAR3, compatible with ColE1-derived plasmids. Gene 158:141-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raivio, T. L., and T. J. Silhavy. 1999. The σE and Cpx regulatory pathways: overlapping but distinct envelope stress responses. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:159-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rawlings, N., and A. Barrett. 1994. Families of serine peptidases. Methods Enzymol. 244:19-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 35.Sawers, G., and M. Jarsch. 1996. Alternative regulation principles for the production of recombinant proteins in Escherichia coli. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 46:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scherrer, S., N. Robas, H. Zouheiry, G. Branlant, and C. Branlant. 1994. Periplasmic aggregation limits the proteolytic maturation of the Escherichia coli penicillin G amidase precursor polypeptide. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 42:85-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shewale, J. G., and H. Sivaraman. 1989. Penicillin acylase: enzyme production and its application in the manufacture of 6-APA. Process Biochem. 24:146-154. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sizmann, D., C. Keilmann, and A. Bock. 1990. Primary structure requirements for the maturation in vivo of penicillin acylase from Escherichia coli ATCC 11105. Eur. J. Biochem. 192:143-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Skorko-Glonek, J., K. Krzewski, B. Lipinska, E. Bertoli, and F. Tanfani. 1995. Comparison of the structure of wild-type HtrA heat shock protease and mutant HtrA proteins. A Fourier transform infrared spectroscopic study J. Biol. Chem. 270:11140-11146. (Erratum, J. Biol. Chem. 270:31413.) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Skorko-Glonek, J., K. Krzewski, G. Zolese, E. Bertoli, and F. Tanfani. 1997. HtrA heat shock protease interacts with phospholipid membranes and undergoes conformational changes. J. Biol. Chem. 272:8974-8982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skorko-Glonek, J., A. Wawrzynow, K. Krzewski, K. Kurpierz, and B. Lipinska. 1995. Site-directed mutagenesis of the HtrA (DegP) serine protease, whose proteolytic activity is indispensable for Escherichia coli survival at elevated temperatures. Gene 163:47-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spiess, C., A. Beil, and M. Ehrmann. 1999. A temperature-dependent switch from chaperone to protease in a widely conserved heat shock protein. Cell 97:339-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sriubolmas, N., W. Panbangred, S. Sriurairatana, and V. Meevootisom. 1997. Localization and characterization of inclusion bodies in recombinant Escherichia coli cells overproducing penicillin G acylase. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 47:373-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Strandberg, L., and S.-O. Enfors. 1991. Factors influencing inclusion body formation in the production of a fused protein in Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:1669-1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strauch, K. L., K. Johnson, and J. Beckwith. 1989. Characterization of degP, a gene required for proteolysis in the cell envelope and essential for growth of Escherichia coli at high temperature. J. Bacteriol. 171:2689-2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thomas, J. G., A. Ayling, and F. Baneyx. 1997. Molecular chaperones, folding catalysts, and the recovery of active recombinant proteins from E. coli. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 66:197-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Waller, P. R., and R. T. Sauer. 1996. Characterization of degQ and degS, Escherichia coli genes encoding homologs of the DegP protease. J. Bacteriol. 178:1146-1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yee, L., and H. W. Blanch. 1992. Recombinant protein expression in high cell density fed-batch cultures of Escherichia coli. Bio/Technology 10:1550-1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]