Abstract

Distinct morphological changes associated with the complex development cycle of the obligate intracellular bacterial pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis have been historically well characterized by microscopy. A number of temporally regulated genes have been characterized previously, suggesting that the chlamydial developmental cycle is regulated at the transcriptional level. This hypothesis was tested by microarray analysis in which the entire C. trachomatis genome was analyzed, providing a comprehensive assessment of global gene regulation throughout the chlamydial developmental cycle. Seven temporally cohesive gene clusters were identified, with 22% (189 genes) of the genome differentially expressed during the developmental cycle. The correlation of these gene clusters with hallmark morphological events of the chlamydial developmental cycle suggests three global stage-specific networks of gene regulation.

Global networks for gene regulation in bacteria adapt the organism to different environments or govern cell cycle developmental changes, as is the case for Bacillus subtilis and Caulobacter crescentus (9, 16, 24). Chlamydiae are phylogenetically deeply separated from other bacterial divisions based on rRNA sequence comparisons (20). In addition, this deep separation is reflected phenotypically by their obligate intracellular lifestyle and their complex developmental cycle (12). Information from the genome sequence (27) and DNA microarray expression profiling studies should elucidate regulatory linkages among chlamydial genes and provide information supporting the molecular bases of global gene regulation during the developmental cycle and their role in the singular biology of this system.

Chlamydiae are extremely successful bacterial pathogens whose representatives are widely distributed in nature. Of all the infectious diseases reported to the U.S. state health departments and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, chlamydial genital tract infections are the most common, with an estimated 4 to 5 million cases occurring annually in the United States (22, 26). Chlamydiae are obligate intracellular pathogens with a developmental cycle that is unique among other bacteria. Following uptake, chlamydiae develop and grow within an intracellular vacuole, called an inclusion, that is distinct from all intracellular vacuolar compartments (23). The chlamydial developmental cycle involves a metabolically inactive, nonreplicating infectious form called the elementary body (EB) that, after entry into the target cell, differentiates into a metabolically active, replicating reticulate body (RB) (12).

The EB and RB are phenotypically distinct. EB are approximately 300 nm in diameter, are osmotically resistant, have highly disulfide bond cross-linked outer membrane proteins, and contain DNA that is exceedingly condensed into an electron-dense nucleoid. RB are approximately 1,000 nm in diameter, are sensitive to osmotic lysis, and contain dispersed DNA (12, 26). Within the first 2 to 6 h following internalization, EB begin differentiating into RB. Over the next several hours, RB increase in number and in size. RB can be observed dividing by binary fission by 12 h postinfection (hpi). After 18 to 24 h, the numbers of RB are maximized, and increasing numbers of RB begin differentiating back to EB, which accumulate within the lumen of the inclusion as the remainder of the RB continue to multiply. Depending on the species or strain, lysis or release from the infected cell occurs approximately 48 to 72 hpi.

Although the developmental cycle of chlamydiae has been well characterized by microscopy, the signals that trigger interconversion of the morphologically distinct forms are unknown. In addition, the mechanisms that control and regulate intracellular development are poorly understood. It has been shown that synthesis of a number of proteins continues throughout development, while other proteins are associated with late-stage differentiation; this pattern of chlamydial protein synthesis is consistent with the structural and functional characteristics of the chlamydial developmental cycle. Thus, previous identification of temporally regulated proteins implicates an ordered system of developmental regulation and suggests that the developmental cycle is ultimately regulated at the transcriptional level (11, 13, 21). These observations led us to hypothesize that a substantial fraction of the chlamydial genome is differentially regulated and coordinately transcribed, serves critical regulatory and functional roles, and mediates the phenotypic changes observed during the developmental cycle.

To identify development stage-specific gene sets, we used whole-genome DNA microarray expression profiling to monitor the transcript abundance of 875 C. trachomatis chromosomal genes (27) throughout the development cycle. We identified 189 genes, comprising 22% of the C. trachomatis genome, that are temporally regulated during the developmental cycle. This analysis provides a foundation for understanding global gene regulation and its role in the intracellular biology of this unique pathogen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chlamydia culture and RNA isolation.

C. trachomatis serovar L2 (434/Bu) was used to infect L929 suspension cultures at a multiplicity of infection of 1. Infections were carried out in suspension cultures because aliquots could be obtained from the same culture at various times postinfection. Cultures were grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Logan, Utah), and 50 μg of vancomycin (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) per ml. For time course studies, at least four independent infections were carried out in which chlamydiae were harvested from infected cells at 6, 12, 18, 24, and 36 hpi. To isolate chlamydial RNA, all steps were conducted on ice or in a refrigerated centrifuge at 4°C. Infected cells were pelleted by centrifugation and sonicated to release infectious organisms as previously described (15). The suspension was then layered on 30% Renografin (Squibb Diagnostics, Princeton, N.J.) and centrifuged for 10 min at 15,267 × g. Following centrifugation, the pelleted chlamydial organisms were suspended in Trizol (Gibco-BRL) and stored at −80°C until RNA extraction.

Preparation of labeled cDNA.

Total chlamydial RNA was extracted from Trizol according to the manufacturer's instructions. Fluorescently labeled cDNA copies of the total RNA pool were prepared by direct incorporation of fluorescent nucleotide analogs during a first-strand reverse transcription reaction. Each labeling reaction (40 μl) consisted of 3 μg of total RNA, 2 nmol of random primers, 0.5 mM each dATP, dCTP, and dGTP, 0.2 mM dTTP, 10 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.3 U of reverse transcriptase (Superscript II, Stratagene) in 1× reaction buffer provided by the manufacturer and 2 nmol of either Cy3-labeled dUTP or Cy5-labeled dUTP (Amersham Pharmacia). RNA samples taken at 6, 12, 18, and 36 hpi were labeled with Cy5-labeled dUTP, and RNA samples taken at 24 hpi were labeled with Cy3-labeled dUTP. The RNA and primers were heated to 98°C for 10 min and snap-cooled in ice water before the remaining reaction components were added. The reverse transcription reaction proceeded for 10 min at 25°C, followed by 2 h at 42°C. Buffer exchange, purification, and concentration of the cDNA products were accomplished by three cycles of diluting the reaction mixture in 0.45 ml of TE buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA) and filtering through Microcon-10 microconcentrators (Amicon, Bedford, Mass.).

Microarray hybridization and data analysis.

DNA arrays containing all 875 open reading frames (ORFs) of C. trachomatis based upon the genome sequence (27) were prepared as previously described in MGUIDE (http://cmgm.stanford.edu/pbrown/mguide) except that the array was printed twice per slide, thereby providing duplicate assessments for each hybridization experiment. Briefly, primers were chosen with the primer program from the GCG package. Each primer was between 20 and 23 bases long and produced a PCR product of between 150 to 800 bases. Primers were produced in the 96-well format by the PAN Facility (Stanford University, Beckman Center, Stanford, Calif.). For each hybridization, the cDNAs from 6, 12, 18, or 36 hpi were compared to those from the 24-hpi time point. The two cDNA pools to be compared were mixed and applied to a DNA array in a hybridization mixture containing 3.5× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate), 0.3% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 10 μg of yeast tRNA. Hybridization took place under a glass coverslip in a 65°C water bath overnight. The slides were washed, dried, and scanned with a GenePix scanner 4000A and the GenePix program (Axon Instruments, Foster City, Calif.).

The resulting 16-bit TIFF images were analyzed with Scanalyze software (http://rana.lbl.gov). Only spots with more than 60% of all pixels having intensities greater than average background intensities were used for analysis, and the data for duplicate readings and each hybridization experiment were analyzed with Cluster and Treeview programs (http://rana.lbl.gov). Arrays were paired according to time point, and genes were sorted (Microsoft Excel) based on ≥3-fold changes by normalized Cy5/Cy3 median ratio. The standard deviation in the change for all data was 0.15. In order to define temporal categories, genes were grouped together based on similar expression profiles throughout all the time points examined with 3-fold ± 0.3-fold differences in transcription. To confirm the temporal expression profiles identified at the 24-hpi time point, direct comparisons between cDNA from organisms at 6 and 12 hpi and 12 and 18 hpi were tested. The results of these direct comparisons provided results congruent to the profiles identified by the 24-hpi time point. Additionally, the fluorescent labels for the 12- and 18-hpi time points were exchanged to ensure that uneven incorporation did not confound the results.

Reverse transcription-PCR.

Total RNA extractions from L929 cells in suspension harvested at 6, 12, 18, 24 and 36 h after infection were performed with Trizol (Gibco-BRL) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Treatment with RQ1 DNase (Promega) followed. Synthesis of cDNA occurred with 8 ng of total RNA with final dNTP concentrations of 25 μM each (Applied Biosystems), 0.2 μM 3′ antisense primer, 40 U of recombinant RNase inhibitor (Promega), and 200 U Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Promega) supplied with a buffer from the manufacturer. Reverse transcription transpired at 65°C for 5 min, 37°C for 1 h, and 75°C for 5 min. It was determined empirically that 8 ng of RNA was required to successfully amplify message from the omcB gene at 24 and 36 h postinfection, as described previously (12), and was therefore used for most of the other genes under investigation in this study.

When cDNA synthesis proved inefficient, the amount of total RNA was increased to 200 ng. Subsequent PCRs included 2.5 μl of cDNA product, 200 μM dNTPs, 0.25 μM each primer, and 1.25 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems). With the Applied Biosystems AB-9700 thermal cycler, 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 55°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 1 min along with a final extension at 72°C for 7 min were used to amplify all genes. Products were electrophoresed on 2.0% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide. A cDNA negative control with RNA without added reverse transcriptase was performed alongside a positive control containing 0.5 μg of C. trachomatis L2 genomic DNA.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The initial technical obstacle in using a microarray approach to determine the transcriptional profile of an obligate intracellular organism is that the vast majority of the RNA present within an infected cell is host RNA, diluting bacterium-specific signals. This difficulty was confirmed by testing total RNA isolated from Chlamydia-infected cells and finding little specific hybridization to the chlamydial microarrays (data not shown). A purification step was performed to enrich for chlamydial RNA; this procedure was conducted at 4°C to minimize mRNA degradation and the induction of procedure-dependent changes in gene expression. Random oligonucleotide hexamers were used to generate labeled cDNA for use in array hybridization.

An alternative to a chlamydial purification step would be the use of 3′ ORF-specific primers for each chlamydial gene. However, it has been shown that random hexamer priming is required for accurate measurement of gene expression levels in bacteria because 3′ ORF-specific primers have unequal hybridization efficiency and because of widely differing degradation rates for the regions complementary to ORF-specific primers (1). The consistency between gene expression data reported here and previously characterized chlamydial transcripts, such as ompA, omcB, and euo (12), supported the conclusion that isolation of Chlamydia-specific mRNA did not systematically confound the results.

To establish the relative abundance of mRNA comprising the chlamydial gene expression profiles, cDNA produced from chlamydiae harvested at 6, 12, 18, or 36 hpi was labeled with Cy5, combined with an equal mass of reference Cy3-labeled cDNA produced from the 24-hpi time point, and hybridized to a chlamydial DNA microarray. Fluorescent ratios greater or less than zero indicate higher or lower mRNA abundance, respectively, relative to the mRNA levels present at 24 hpi. cDNA from 24 hpi was chosen as the reference to assess the gene-specific mRNA abundance for each of the other time points because (i) 24 hpi is near the metabolic and developmental midpoint, (ii) at 24 hpi the chlamydial inclusion is quite large, consisting mostly of RB, with only a few EB and intermediate forms present, and (iii) after 24 hpi, the developmental cycle becomes increasingly asynchronous as a growing number of RB convert into EB.

The data for 62 genes were not evaluated in the complete analysis because they included one or more time points for which the data could not be confidently compared. In every case this was due to a low fluorescence signal at each time point. Thus, these genes are likely not transcribed, such as three genes that have been deleted from the serovar L2 genome or are constitutively transcribed at low levels under the tested growth conditions.

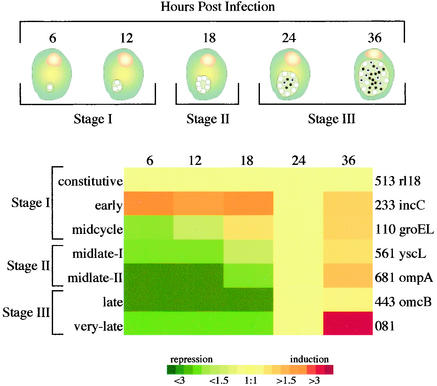

With 24 hpi as the comparative reference, changes in transcript abundance were detected, and seven congruous temporal clusters were defined, suggesting linked transcriptional regulation among genes within each cluster (Fig. 1). The complete data set is available online (http://chlamydia-www.berkeley.edu:4231/). We used a conservative, albeit arbitrary, cutoff of threefold (± 0.3-fold, representing 2 standard deviations of all values) changes for our analysis. Cluster analysis is sensitive to the cutoff used; a lower value will produce more clusters, and higher values will produce fewer clusters. The selection of a threefold change produced clusters that appeared consistent with the known regulation of the few genes previously characterized and emphasized prominent temporal shifts in gene transcription.

FIG. 1.

Temporally coordinated phenotypic changes during chlamydial development cycle in relation to transcriptional clusters and development stage. Clustered expression profiles for single gene representatives from each of the temporal clusters are illustrated. Expression profiles of genes are in rows, with temporal progression from left to right. Expression profiles were clustered with Cluster software and plotted with Treeview software. A complete list of all the genes in each temporal cluster is available (http://chlamydia-www.berkeley.edu:4231/).

Coupling cluster analysis data with developmental cycle processes permitted the arrangement of chlamydial profiles into three global and coordinately regulated developmental stages (Fig. 1). These developmental stages reflect prominent shifts in gene transcription taking place throughout the developmental cycle and correlate with key phenotypic changes taking place. Stage I genes are expressed early following infection and consist of three temporal clusters: the early cluster, the constitutive gene cluster, and the midcycle cluster. Stage II is represented by genes transcriptionally activated by 18 hpi and contains two clusters, midlate I and midlate II. Stage III contains genes which were not actively transcribed until 24 hpi and comprises the late temporal cluster and the very late cluster, which consists of genes whose transcription is significantly increased at 36 hpi.

Stage I.

Developmental stage I is represented by three temporal clusters containing genes whose transcription is initiated within 12 hpi. Genes that were expressed early, at 6 hpi, and continued to be expressed at relatively the same level throughout the developmental cycle were designated the constitutive cluster. This is the largest temporal category, with 612 genes (71% of the genome). An example of a typical gene from this cluster is the well-characterized euo gene. Historically, the euo transcript was shown to be expressed immediately upon infection and was therefore referred to as an early chlamydial gene (30). However, upon further examination, it was shown that the euo transcript is expressed not only early but at consistently similar levels throughout the developmental cycle as well (12). Likewise, with microarray analysis, we found that euo, as well as all of the genes from the constitutive cluster, was expressed early (6 hpi) and at consistent rates for all the time points assayed.

The majority of the genes comprising the constitutive cluster are members of the translational functional group (27); a subset of this category, the ribosomal genes, account for 13% of this cluster. Other functional groups (27) accounting for a large number of genes within this cluster are those of the DNA replication, transcriptional, transport-related, energy compound acquisition, and membrane energetics groups. Based upon the functional groups (27) represented, we infer that genes within the constitutive cluster are involved in basic cellular functions, the transport of nutrients needed for those functions, and those cellular processes necessary for initiating chlamydial growth.

The second stage I cluster, designated early, consists of only two genes (oppA and incC) whose transcripts were expressed at high levels in the initial stages of the infection and then fell to constitutive expression levels later in the developmental cycle (Table 1). This transcriptional profile was further supported by a direct comparison between cDNAs from 6 and 12 hpi (data not shown). oppA encodes an oligopeptide binding protein that was maximally transcribed at 6, 12, and 18 hpi and then declined precipitously, suggesting that the acquisition of peptide substrates might be essential for triggering early differentiation events. The inclusion membrane protein-encoding gene incC is a member of a family of paralogues that are secreted by the type III secretion system and localized to the membrane of the chlamydial vacuole (29). The temporal expression profile of oppA and incC implies that they provide critical functions necessary for the initial stages of the infection but, unlike constitutive cluster genes, are not required in abundance late in the developmental cycle.

TABLE 1.

Stage-specific genes identified by microarray analysisa

| Stage | Cluster | ORF | Gene | Change (fold) at time (hpi):

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-24 | 12-24 | 18-24 | 24-36 | ||||

| I | Early | 175 | oppA | 4.9 ± 0.66 | 4.2 ± 0.46 | 4.3 ± 0.50 | 1.6 ± 0.11 |

| 233 | incC | 2.7 ± 0.24 | 2.3 ± 0.18 | 2.6 ± 0.30 | 1.5 ± 0.04 | ||

| Midcycle | 110 | groEL | −2.9 ± 0.10 | −1.6 ± 0.04 | 1.2 ± 0.04 | 1.4 ± 0.07 | |

| II | Midlate I | 013 | cydA | −3.0 ± 0.03 | −3.0 ± 0.03 | −1.6 ± 0.08 | 1.4 ± 0.08 |

| 014 | cydB | −3.8 ± 0.03 | −3.8 ± 0.02 | −2.1 ± 0.04 | 1.4 ± 0.07 | ||

| 043 | −3.1 ± 0.03 | −3.1 ± 0.02 | −1.8 ± 0.05 | 1.2 ± 0.06 | |||

| 045 | pepA | −4.2 ± 0.04 | −4.2 ± 0.04 | −1.6 ± 0.07 | 1.1 ± 0.02 | ||

| 048 | yraL | −3.8 ± 0.04 | −4.0 ± 0.02 | −2.5 ± 0.04 | 1.4 ± 0.06 | ||

| 053 | −2.9 ± 0.01 | −2.9 ± 0.02 | −1.7 ± 0.05 | 1.7 ± 0.12 | |||

| 062 | tyrS | −3.6 ± 0.02 | −3.6 ± 0.04 | −1.6 ± 0.06 | 1.5 ± 0.08 | ||

| 066 | −6.1 ± 0.01 | −4.1 ± 0.03 | −1.3 ± 0.05 | 1.1 ± 0.10 | |||

| 089 | lcrE | −4.8 ± 0.01 | −4.8 ± 0.01 | −1.9 ± 0.05 | −1.4 ± 0.04 | ||

| 090 | lcrD | −6.4 ± 0.02 | −5.9 ± 0.01 | −1.7 ± 0.07 | −1.6 ± 0.03 | ||

| 215 | dhnA | −2.8 ± 0.06 | −2.9 ± 0.06 | −1.5 ± 0.09 | 1.3 ± 0.05 | ||

| 216 | xasA | −3.2 ± 0.25 | −5.4 ± 0.02 | −1.9 ± 0.06 | −1.5 ± 0.04 | ||

| 218 | surE | −3.0 ± 0.05 | −3.7 ± 0.03 | −2.2 ± 0.05 | 1.3 ± 0.07 | ||

| 230 | −2.9 ± 0.03 | −2.8 ± 0.01 | −1.3 ± 0.07 | 1.6 ± 0.06 | |||

| 237 | fabG | −3.4 ± 0.02 | −2.7 ± 0.02 | −1.4 ± 0.06 | 1.2 ± 0.03 | ||

| 238 | fabD | −3.8 ± 0.03 | −3.7 ± 0.01 | −1.3 ± 0.07 | 1.1 ± 0.04 | ||

| 239 | fabH | −2.8 ± 0.03 | −3.2 ± 0.03 | 1.0 ± 0.05 | 1.3 ± 0.06 | ||

| 241 | yaeT | −2.7 ± 0.03 | −2.7 ± 0.02 | 1.0 ± 0.08 | 1.1 ± 0.05 | ||

| 259 | −2.8 ± 0.05 | −2.8 ± 0.01 | −1.7 ± 0.06 | 1.2 ± 0.04 | |||

| 267 | himD | −6.1 ± 0.03 | −6.1 ± 0.01 | −2.4 ± 0.06 | 1.8 ± 0.08 | ||

| 273 | −3.1 ± 0.02 | −3.1 ± 0.02 | −1.6 ± 0.08 | 1.3 ± 0.12 | |||

| 278 | nqr2 | −7.0 ± 0.01 | −4.9 ± 0.01 | −1.2 ± 0.10 | −1.3 ± 0.06 | ||

| 289 | −4.3 ± 0.02 | −4.3 ± 0.02 | −2.0 ± 0.06 | 1.7 ± 0.11 | |||

| 313 | tal | −5.7 ± 0.03 | −5.3 ± 0.01 | −1.7 ± 0.06 | −1.1 ± 0.06 | ||

| 328 | tpiA | −2.7 ± 0.02 | −2.7 ± 0.02 | 1.0 ± 0.10 | −1.1 ± 0.04 | ||

| 332 | pykF | −2.7 ± 0.02 | −2.7 ± 0.03 | −1.3 ± 0.07 | 1.1 ± 0.11 | ||

| 334 | dnaX | −4.0 ± 0.03 | −3.0 ± 0.02 | −1.2 ± 0.12 | 1.0 ± 0.06 | ||

| 344 | lon | −7.1 ± 0.01 | −7.1 ± 0.04 | −2.5 ± 0.13 | 1.9 ± 0.13 | ||

| 346 | elaC | −2.8 ± 0.04 | −3.4 ± 0.03 | −2.6 ± 0.04 | 1.4 ± 0.08 | ||

| 360 | −4.8 ± 0.01 | −4.8 ± 0.02 | −1.9 ± 0.05 | −1.4 ± 0.03 | |||

| 372 | −4.9 ± 0.05 | −4.9 ± 0.02 | −2.5 ± 0.06 | 1.4 ± 0.07 | |||

| 373 | −4.3 ± 0.03 | −4.3 ± 0.02 | −1.9 ± 0.07 | −2.1 ± 0.05 | |||

| 376 | mdh | −5.9 ± 0.01 | −4.8 ± 0.02 | −2.2 ± 0.07 | 1.5 ± 0.11 | ||

| 377 | ltuA | −4.3 ± 0.02 | −5.2 ± 0.03 | −1.9 ± 0.06 | 2.1 ± 0.33 | ||

| 378 | pgi | −3.3 ± 0.01 | −3.3 ± 0.05 | −1.9 ± 0.05 | 1.2 ± 0.06 | ||

| 385 | yefF | 3.2 ± 0.07 | −3.5 ± 0.08 | −1.9 ± 0.04 | 1.4 ± 0.13 | ||

| 386 | −4.3 ± 0.02 | −4.3 ± 0.02 | −2.1 ± 0.07 | 1.5 ± 0.06 | |||

| 408 | ispA | −3.2 ± 0.04 | −3.2 ± 0.04 | −1.6 ± 0.03 | 1.0 ± 0.05 | ||

| 413 | pmpB | −3.7 ± 0.04 | −3.7 ± 0.01 | −1.9 ± 0.07 | −1.4 ± 0.04 | ||

| 414 | pmpC | −4.7 ± 0.01 | −4.7 ± 0.01 | −1.6 ± 0.09 | −1.1 ± 0.05 | ||

| 430 | dapF | −2.8 ± 0.02 | −4.6 ± 0.03 | −1.1 ± 0.10 | −1.3 ± 0.03 | ||

| 431 | clpP | −3.3 ± 0.02 | −2.8 ± 0.01 | −1.0 ± 0.10 | −1.1 ± 0.03 | ||

| 432 | glyA | −3.8 ± 0.02 | −4.2 ± 0.01 | −1.5 ± 0.08 | 1.2 ± 0.07 | ||

| 455 | murA | −2.9 ± 0.01 | −2.9 ± 0.03 | −1.7 ± 0.08 | 1.7 ± 0.07 | ||

| 476 | −8.9 ± 0.01 | −7.6 ± 0.02 | −2.0 ± 0.07 | 1.4 ± 0.07 | |||

| 480 | dppA | −2.8 ± 0.02 | −3.1 ± 0.03 | 1.0 ± 0.08 | −1.5 ± 0.02 | ||

| 496 | pgsA | −4.0 ± 0.01 | −3.6 ± 0.02 | −1.5 ± 0.04 | 1.1 ± 0.05 | ||

| 500 | ndk | −4.2 ± 0.02 | −3.7 ± 0.03 | −1.1 ± 0.07 | −1.3 ± 0.04 | ||

| 504 | −4.2 ± 0.03 | −4.1 ± 0.01 | −2.1 ± 0.07 | −1.0 ± 0.04 | |||

| 505 | gapA | −3.3 ± 0.03 | −3.3 ± 0.02 | −1.3 ± 0.07 | 1.5 ± 0.10 | ||

| 531 | lpxA | −3.1 ± 0.03 | −3.1 ± 0.05 | 1.2 ± 0.12 | 1.0 ± 0.05 | ||

| 535 | yciA | −3.5 ± 0.02 | −3.5 ± 0.02 | −1.7 ± 0.07 | 1.8 ± 0.09 | ||

| 544 | uhpC | −8.9 ± 0.01 | −8.9 ± 0.01 | −1.4 ± 0.07 | −1.4 ± 0.03 | ||

| 550 | −3.5 ± 0.01 | −3.5 ± 0.03 | −1.9 ± 0.04 | −1.2 ± 0.07 | |||

| 553 | fmu | −4.5 ± 0.03 | −3.3 ± 0.06 | −1.0 ± 0.17 | 1.2 ± 0.04 | ||

| 559 | yscJ | −4.4 ± 0.01 | −4.4 ± 0.04 | −1.9 ± 0.09 | 1.2 ± 0.06 | ||

| 561 | yscL | 3.1 ± 0.02 | −3.1 ± 0.14 | −1.6 ± 0.11 | 1.3 ± 0.16 | ||

| 584 | −3.2 ± 0.01 | −3.2 ± 0.02 | −1.1 ± 0.04 | 1.0 ± 0.12 | |||

| 590 | −2.8 ± 0.02 | −3.4 ± 0.02 | −1.7 ± 0.08 | −1.2 ± 0.06 | |||

| 600 | pal | −4.1 ± 0.40 | −4.1 ± 0.01 | −2.0 ± 0.04 | −1.2 ± 0.06 | ||

| 610 | −7.6 ± 0.01 | −6.5 ± 0.02 | −1.1 ± 0.11 | 1.4 ± 0.08 | |||

| 611 | −2.9 ± 0.01 | −2.9 ± 0.03 | −1.1 ± 0.10 | 1.7 ± 0.06 | |||

| 618 | −2.8 ± 0.02 | −3.0 ± 0.01 | −1.3 ± 0.07 | −1.1 ± 0.04 | |||

| 621 | −4.3 ± 0.03 | −4.3 ± 0.01 | −2.2 ± 0.06 | 1.3 ± 0.07 | |||

| 634 | nqrA | −3.3 ± 0.02 | −3.3 ± 0.01 | −1.8 ± 0.07 | 1.0 ± 0.07 | ||

| 635 | −2.7 ± 0.01 | −2.7 ± 0.02 | −2.3 ± 0.04 | 1.2 ± 0.12 | |||

| 645 | −3.0 ± 0.02 | −3.0 ± 0.04 | −2.0 ± 0.06 | 1.2 ± 0.05 | |||

| 650 | recA | −2.8 ± 0.03 | −2.8 ± 0.01 | −1.4 ± 0.05 | 1.4 ± 0.10 | ||

| 662 | nemA | −3.1 ± 0.02 | −3.1 ± 0.01 | −1.7 ± 0.04 | 1.2 ± 0.02 | ||

| 663 | −2.7 ± 0.01 | −3.6 ± 0.02 | −1.2 ± 0.10 | 1.1 ± 0.06 | |||

| 664 | −5.7 ± 0.01 | −5.9 ± 0.02 | −1.4 ± 0.08 | −1.7 ± 0.02 | |||

| 665 | −2.8 ± 0.02 | −2.7 ± 0.06 | −1.3 ± 0.09 | −2.2 ± 0.03 | |||

| 666 | −5.2 ± 0.01 | −5.2 ± 0.02 | −1.4 ± 0.08 | −1.6 ± 0.01 | |||

| 667 | −3.2 ± 0.03 | −3.2 ± 0.02 | −1.8 ± 0.05 | −1.3 ± 0.03 | |||

| 668 | −9.6 ± 0.01 | −4.9 ± 0.01 | −1.8 ± 0.06 | −1.5 ± 0.04 | |||

| 669 | yscN | −6.2 ± 0.01 | −6.2 ± 0.01 | −1.4 ± 0.07 | −1.6 ± 0.03 | ||

| 670 | −3.8 ± 0.01 | −3.8 ± 0.02 | −1.6 ± 0.05 | −1.5 ± 0.02 | |||

| 671 | −3.1 ± 0.03 | −3.1 ± 0.02 | −1.6 ± 0.07 | −1.4 ± 0.05 | |||

| 672 | fliN | −3.5 ± 0.02 | −3.5 ± 0.02 | −1.5 ± 0.06 | −1.5 ± 0.03 | ||

| 700 | −2.8 ± 0.01 | −2.8 ± 0.03 | −1.4 ± 0.09 | −1.0 ± 0.04 | |||

| 701 | secA | −3.1 ± 0.01 | −3.1 ± 0.03 | −2.6 ± 0.04 | 1.3 ± 0.06 | ||

| 708 | −3.8 ± 0.02 | −3.8 ± 0.01 | −1.5 ± 0.07 | −1.4 ± 0.03 | |||

| 709 | mreB | −2.8 ± 0.02 | −2.8 ± 0.03 | −1.3 ± 0.06 | 1.2 ± 0.05 | ||

| 710 | pckA | −6.0 ± 0.01 | −6.0 ± 0.01 | −1.7 ± 0.05 | −1.0 ± 0.05 | ||

| 734 | −3.1 ± 0.03 | −4.4 ± 0.03 | −2.0 ± 0.05 | 2.2 ± 0.08 | |||

| 752 | efp | −3.6 ± 0.04 | −3.6 ± 0.03 | −1.6 ± 0.04 | 2.1 ± 0.15 | ||

| 768 | ybeB | −2.7 ± 0.02 | −2.9 ± 0.01 | 1.0 ± 0.06 | 1.2 ± 0.08 | ||

| 770 | fabF | −3.0 ± 0.02 | −3.0 ± 0.02 | −1.5 ± 0.07 | 1.2 ± 0.09 | ||

| 816 | glmS | −2.9 ± 0.02 | −2.9 ± 0.01 | −1.7 ± 0.07 | −1.2 ± 0.05 | ||

| 819 | yccA | −9.6 ± 0.01 | −4.7 ± 0.12 | −2.5 ± 0.03 | 1.3 ± 0.03 | ||

| 827 | nrdA | −3.8 ± 0.02 | −3.8 ± 0.01 | −2.1 ± 0.04 | 1.1 ± 0.05 | ||

| 828 | nrdB | −4.2 ± 0.06 | −4.2 ± 0.01 | −2.3 ± 0.04 | 1.3 ± 0.07 | ||

| 842 | pnp | −3.1 ± 0.01 | −3.1 ± 0.02 | −1.2 ± 0.06 | 1.2 ± 0.05 | ||

| 870 | pmpF | −7.8 ± 0.01 | −7.8 ± 0.01 | −2.6 ± 0.04 | 1.1 ± 0.06 | ||

| 871 | pmpG | −14.0 ± 0.01 | −14.0 ± 0.01 | −2.6 ± 0.04 | −1.1 ± 0.07 | ||

| 872 | pmpH | −6.4 ± 0.01 | −6.4 ± 0.01 | −2.5 ± 0.04 | −1.1 ± 0.04 | ||

| 874 | pmpI | −8.6 ± 0.01 | −8.6 ± 0.01 | −2.7 ± 0.05 | 1.3 ± 0.09 | ||

| Midlate II | 049 | 11.2 ± 0.03 | −11.2 ± 0.01 | −5.4 ± 0.02 | 2.3 ± 0.11 | ||

| 051 | −5.1 ± 0.01 | −5.1 ± 0.01 | −2.7 ± 0.04 | 1.5 ± 0.08 | |||

| 142 | −22.1 ± 0.01 | −17.1 ± 0.02 | −5.7 ± 0.02 | 2.3 ± 0.17 | |||

| 143 | −12.2 ± 0.03 | −16.4 ± 0.02 | −5.6 ± 0.03 | 2.2 ± 0.14 | |||

| 144 | −10.9 ± 0.01 | −11.5 ± 0.01 | −5.6 ± 0.02 | 2.1 ± 0.15 | |||

| 286 | clpC | −16.1 ± 0.01 | −10.2 ± 0.01 | −3.6 ± 0.04 | 1.5 ± 0.07 | ||

| 491 | rho | −10.3 ± 0.02 | −8.8 ± 0.01 | −3.9 ± 0.03 | 1.7 ± 0.08 | ||

| 492 | yacE | −9.0 ± 0.01 | −9.4 ± 0.01 | −2.7 ± 0.03 | 1.6 ± 0.06 | ||

| 494 | sohB | −12.3 ± 0.01 | −11.0 ± 0.01 | −4.2 ± 0.03 | 1.9 ± 0.16 | ||

| 674 | yscC | −12.4 ± 0.01 | −12.4 ± 0.01 | −3.5 ± 0.03 | 1.2 ± 0.05 | ||

| 681 | ompA | −15.7 ± 0.01 | −11.4 ± 0.01 | −3.1 ± 0.03 | 1.7 ± 0.10 | ||

| 713 | ompB | −9.6 ± 0.01 | −9.6 ± 0.01 | −5.7 ± 0.02 | 1.8 ± 0.07 | ||

| 783 | −8.1 ± 0.01 | −8.1 ± 0.01 | −3.4 ± 0.04 | 1.8 ± 0.11 | |||

| 798 | glgA | −33.9 ± 0.01 | −23.9 ± 0.01 | −7.4 ± 0.02 | 2.5 ± 0.15 | ||

| III | Late | 001 | −3.8 ± 0.01 | −3.8 ± 0.03 | −3.8 ± 0.02 | 1.5 ± 0.14 | |

| 005 | −9.7 ± 0.02 | −11.3 ± 0.01 | −11.3 ± 0.01 | 1.6 ± 0.26 | |||

| 016 | −8.4 ± 0.01 | −8.4 ± 0.01 | −5.0 ± 0.02 | 1.8 ± 0.10 | |||

| 017 | −5.0 ± 0.05 | −3.9 ± 0.04 | −3.2 ± 0.06 | 1.8 ± 0.09 | |||

| 040 | ruvB | −6.0 ± 0.01 | −6.0 ± 0.01 | −3.4 ± 0.04 | 2.0 ± 0.08 | ||

| 041 | −7.9 ± 0.01 | −7.9 ± 0.01 | −3.3 ± 0.02 | 2.1 ± 0.11 | |||

| 046 | hctB | −7.2 ± 0.01 | −5.9 ± 0.01 | −5.9 ± 0.03 | −1.4 ± 0.05 | ||

| 050 | −4.4 ± 0.02 | −4.4 ± 0.03 | −3.1 ± 0.04 | 1.1 ± 0.05 | |||

| 052 | hemN | −3.1 ± 0.03 | −3.1 ± 0.02 | −3.2 ± 0.04 | 1.9 ± 0.08 | ||

| 073 | −5.8 ± 0.01 | −5.8 ± 0.04 | −5.8 ± 0.02 | −1.3 ± 0.07 | |||

| 080 | ltuB | −6.6 ± 0.01 | −6.6 ± 0.01 | −6.6 ± 0.02 | 1.0 ± 0.10 | ||

| 082 | −10.6 ± 0.01 | −10.6 ± 0.01 | −10.6 ± 0.01 | 1.5 ± 0.21 | |||

| 083 | −3.5 ± 0.02 | −3.5 ± 0.02 | −3.5 ± 0.03 | −1.0 ± 0.14 | |||

| 084 | −3.1 ± 0.01 | −3.1 ± 0.02 | −4.2 ± 0.03 | 1.4 ± 0.07 | |||

| 140 | ypdP | −3.3 ± 0.03 | −3.5 ± 0.01 | −3.0 ± 0.05 | 1.7 ± 0.15 | ||

| 181 | −9.4 ± 0.01 | −9.4 ± 0.01 | −9.4 ± 0.01 | 1.1 ± 0.19 | |||

| 212 | yqdE | 1.1 ± 0.38 | −3.1 ± 0.01 | −3.1 ± 0.02 | 1.1 ± 0.13 | ||

| 213 | rpiA | −5.3 ± 0.02 | −5.3 ± 0.02 | −5.3 ± 0.03 | 1.6 ± 0.24 | ||

| 214 | 1.2 ± 0.43 | −9.8 ± 0.01 | −9.8 ± 0.06 | 1.2 ± 0.20 | |||

| 236 | acpP | −3.4 ± 0.01 | −3.4 ± 0.01 | −3.2 ± 0.03 | 1.6 ± 0.09 | ||

| 248 | glgP | −3.0 ± 0.03 | −3.0 ± 0.02 | −3.2 ± 0.04 | 1.2 ± 0.05 | ||

| 288 | −7.5 ± 0.02 | −13.0 ± 0.01 | −8.4 ± 0.01 | 1.5 ± 0.13 | |||

| 356 | yyaL | −9.3 ± 0.02 | −9.0 ± 0.04 | −9.9 ± 0.02 | −1.6 ± 0.06 | ||

| 365 | −5.6 ± 0.01 | −5.6 ± 0.04 | −5.6 ± 0.02 | −1.1 ± 0.14 | |||

| 369 | aroB | −12.9 ± 0.01 | −12.9 ± 0.01 | −18.3 ± 0.01 | 1.9 ± 0.21 | ||

| 375 | −5.9 ± 0.02 | −5.9 ± 0.03 | −5.6 ± 0.02 | 1.7 ± 0.24 | |||

| 392 | yprS | −3.5 ± 0.05 | −5.5 ± 0.06 | −5.5 ± 0.05 | −1.7 ± 0.08 | ||

| 394 | hrcA | −5.8 ± 0.01 | −5.8 ± 0.01 | −3.8 ± 0.02 | 2.1 ± 0.11 | ||

| 395 | grpE | −4.2 ± 0.04 | −3.8 ± 0.01 | −2.9 ± 0.05 | 1.5 ± 0.15 | ||

| 396 | dnaK | −4.4 ± 0.03 | −4.4 ± 0.02 | −2.9 ± 0.04 | 1.9 ± 0.12 | ||

| 441 | tsp | −2.9 ± 0.03 | −2.9 ± 0.03 | −3.8 ± 0.04 | −1.6 ± 0.08 | ||

| 442 | crpA | −4.1 ± 0.04 | −4.1 ± 0.01 | −5.3 ± 0.02 | 1.3 ± 0.01 | ||

| 443 | omcB | −18.4 ± 0.01 | −18.4 ± 0.01 | −17.3 ± 0.01 | 1.1 ± 0.12 | ||

| 444 | omcA | −13.3 ± 0.01 | −13.3 ± 0.01 | −13.3 ± 0.01 | 1.6 ± 0.20 | ||

| 456 | −9.2 ± 0.01 | −9.2 ± 0.01 | −8.6 ± 0.01 | −1.2 ± 0.04 | |||

| 457 | yebC | −6.7 ± 0.03 | −3.1 ± 0.09 | −2.8 ± 0.03 | 1.3 ± 0.09 | ||

| 458 | yhhY | −2.8 ± 0.02 | −2.8 ± 0.03 | −3.5 ± 0.03 | 1.3 ± 0.06 | ||

| 459 | prfB | −2.8 ± 0.02 | −2.8 ± 0.08 | −3.1 ± 0.04 | 1.4 ± 0.13 | ||

| 489 | glgC | −3.2 ± 0.02 | −3.2 ± 0.01 | −3.2 ± 0.02 | −1.1 ± 0.03 | ||

| 493 | polA | −7.3 ± 0.03 | −7.6 ± 0.02 | −4.5 ± 0.03 | 1.7 ± 0.08 | ||

| 546 | −6.4 ± 0.01 | −6.4 ± 0.01 | −7.1 ± 0.01 | −1.0 ± 0.08 | |||

| 552 | −7.2 ± 0.02 | −5.4 ± 0.02 | −3.9 ± 0.03 | −1.1 ± 0.08 | |||

| 565 | −6.6 ± 0.01 | −6.6 ± 0.01 | −4.2 ± 0.03 | 2.0 ± 0.17 | |||

| 576 | lcrH | −17.3 ± 0.01 | −17.3 ± 0.01 | −21.4 ± 0.01 | −1.1 ± 0.13 | ||

| 577 | −4.2 ± 0.02 | −4.2 ± 0.02 | −4.2 ± 0.04 | 1.0 ± 0.10 | |||

| 578 | −14.6 ± 0.01 | −14.6 ± 0.01 | −14.6 ± 0.01 | −1.1 ± 0.12 | |||

| 579 | −14.8 ± 0.01 | −14.8 ± 0.01 | −14.8 ± 0.01 | 1.2 ± 0.13 | |||

| 619 | −3.9 ± 0.07 | −3.7 ± 0.03 | −3.7 ± 0.05 | −2.6 ± 0.06 | |||

| 620 | −20.8 ± 0.01 | −12.3 ± 0.03 | −6.0 ± 0.03 | 1.5 ± 0.13 | |||

| 622 | −11.8 ± 0.02 | −8.0 ± 0.01 | −8.0 ± 0.03 | −1.6 ± 0.06 | |||

| 643 | topA | −3.4 ± 0.03 | −3.4 ± 0.02 | −3.7 ± 0.04 | −1.5 ± 0.05 | ||

| 659 | −4.3 ± 0.01 | −4.3 ± 0.02 | −3.6 ± 0.03 | 2.2 ± 0.22 | |||

| 660 | gyrA | −5.0 ± 0.02 | −5.0 ± 0.02 | −5.4 ± 0.03 | 2.3 ± 0.22 | ||

| 693 | pgk | −5.1 ± 0.01 | −5.1 ± 0.01 | −3.1 ± 0.04 | 1.8 ± 0.08 | ||

| 694 | −5.1 ± 0.06 | −5.1 ± 0.02 | −5.1 ± 0.01 | −2.2 ± 0.06 | |||

| 695 | −5.2 ± 0.02 | −5.2 ± 0.03 | −5.2 ± 0.03 | −2.0 ± 0.05 | |||

| 711 | −2.8 ± 0.04 | −2.8 ± 0.02 | −4.2 ± 0.03 | −1.3 ± 0.03 | |||

| 712 | −5.5 ± 0.01 | −5.5 ± 0.01 | −5.4 ± 0.03 | −1.6 ± 0.03 | |||

| 733 | −6.6 ± 0.01 | −6.6 ± 0.01 | −3.2 ± 0.04 | 2.3 ± 0.10 | |||

| 775 | −3.3 ± 0.02 | −3.3 ± 0.15 | −4.0 ± 0.02 | 1.8 ± 0.14 | |||

| 776 | aas | −2.8 ± 0.03 | −2.8 ± 0.02 | −2.8 ± 0.07 | 1.5 ± 0.15 | ||

| 813 | −2.8 ± 0.01 | −2.8 ± 0.02 | −2.8 ± 0.02 | 2.5 ± 0.26 | |||

| 814 | −12.0 ± 0.01 | −5.6 ± 0.01 | −5.6 ± 0.02 | 1.9 ± 0.20 | |||

| 840 | mesJ | −4.3 ± 0.04 | −3.6 ± 0.03 | −3.4 ± 0.04 | −1.0 ± 0.12 | ||

| 841 | ftsH | −3.5 ± 0.01 | −3.5 ± 0.10 | −3.5 ± 0.02 | 1.3 ± 0.03 | ||

| 848 | −2.8 ± 0.01 | −2.8 ± 0.04 | −3.9 ± 0.07 | −1.3 ± 0.05 | |||

| 864 | xerC/D | −3.2 ± 0.06 | −3.2 ± 0.14 | −3.4 ± 0.04 | 1.1 ± 0.11 | ||

| 868 | −4.4 ± 0.30 | −4.8 ± 0.20 | −3.5 ± 0.04 | 1.8 ± 0.27 | |||

| 869 | pmpE | −5.5 ± 0.02 | −5.5 ± 0.01 | −3.1 ± 0.04 | −1.1 ± 0.07 | ||

| 875 | −22.1 ± 0.01 | −23.2 ± 0.01 | −11.9 ± 0.01 | 1.8 ± 0.21 | |||

| Very late | 035 | bpl | −4.4 ± 0.03 | −4.9 ± 0.02 | −3.4 ± 0.06 | 3.4 ± 0.36 | |

| 081 | −3.5 ± 0.01 | −3.5 ± 0.05 | −3.5 ± 0.04 | 10.4 ± 0.43 | |||

| 147 | −1.1 ± 0.09 | −2.1 ± 0.05 | −1.8 ± 0.08 | 3.5 ± 0.51 | |||

| 249 | 1.0 ± 0.01 | 1.0 ± 0.10 | −1.4 ± 0.09 | 2.9 ± 0.25 | |||

| 702 | −13.9 ± 0.01 | −13.9 ± 0.01 | −5.3 ± 0.03 | 2.7 ± 0.01 | |||

DNA microarray analysis was used to measure the abundance of mRNA levels at 6, 12, 18, and 36 hpi compared to that present at 24 hpi. Differences in mRNA levels are listed as mean changes ± standard error for each corresponding time point. Changes were calculated by averaging the data from eight microarray experiments on four biological sample sets.

The third stage I cluster, designated the midcycle, consists of only one transcript, groEL. Because this gene is not optimally transcribed until 12 hpi, it is not likely to be essential for initiating early differentiation events, but instead may be needed in abundance for processes involved in growth and cellular division.

Six hours postinfection was the first time point chosen to be analyzed because it was the earliest time point at which a sufficient amount of chlamydia-specific mRNA could be obtained. We reasoned that 6 hpi would serve as a sufficiently early time point, as it has been reported that transcripts detected at 2 hpi or earlier are detected at 6 hpi as well (12, 25), perhaps due to the stochastic process of chlamydial infection in vitro. Although not previously described in the literature, it is possible that there are genes that are upregulated immediately after infection and whose expression levels fall to either constitutive levels or undetectable levels by 6 hpi. Nevertheless, it is surprising that so few genes are differentially regulated during the initiation of EB to RB reorganization. This suggests that developmental reorganization is a process involving the transcription of the majority of genes early. In addition, genes expressed very late may provide prepackaged proteins in EB that are posttranslationally activated and participate in early biological events following infection. Alternatively, this process could be regulated by genes whose transcripts did not meet the threefold change criterion.

Stage II.

Developmental stage II is composed of two clusters of genes whose transcript abundance is significantly increased by 18 hpi and then remains at similar levels (midlate I cluster) for the remainder of the developmental cycle or continues to increase (midlate II cluster). This transcriptional profile would predict a greater abundance in the amount of transcript present at 18 hpi than at 12 hpi. To confirm the transcriptional profile of these genes, a direct comparison was made between the cDNAs from 6 and 12 hpi and the cDNAs from 12 and 18 hpi. Microarray analysis of samples from the 6- and 12-hpi time points revealed no significant change between the levels of transcripts present at these times. However, the direct comparison between the cDNAs from 12 and 18 hpi confirmed the increase of transcripts from the stage II genes at 18 hpi (data not shown).

Eighteen hours postinfection is the point in the developmental cycle when RB production is reaching maximal levels and some RB reorganization is initiated. The midlate I cluster consists of genes whose products represent a variety of functions, including cell envelope biogenesis components (18%), energy metabolism (11%), type III secretion (5%), protein folding (3%), and DNA replication, modification, repair, and recombination (4%) (Table 1). Chlamydia-specific hypothetical genes compose 27% of this cluster but are functionally uncharacterized. Five of 12 genes involved with energy metabolism, including those for glycolysis-gluconeogenesis, are maximally expressed at this time, suggesting a shift from early dependence on host cell pools of ATP that are transported by constitutively expressed ADP/ATP translocases. Transcription of six of the nine polymorphic membrane protein (pmp) family genes is coordinately upregulated by 18 hpi. A number of genes involved in cellular processes are produced at this time, including three signal transduction genes and two protease genes, clpP and lon, temporally linking these with late cellular events in chlamydiae. Also present within this cluster are genes from the DNA modification group, including integration host factor (himD) and an SWI/SNF family helicase (CT708). These genes are thought to play a role in chlamydial DNA condensation, a hallmark event in the transition from RB to EB.

The midlate II cluster consists of genes displaying large negative changes for both 6 and 12 hpi, followed by a markedly smaller negative change for 18 hpi (Table 1). Thus, genes in this cluster, although not maximally induced until 24 hpi, have initiated significant transcription by 18 hpi. In chlamydiae, there is a biological precedent that provides a molecular basis for this cluster. Two transcripts with different 5′ termini are produced from the ompA gene at different times during the developmental cycle (28). One transcript is detected relatively early in the infection, and transcription of the second is initiated late, resulting in the presence of two transcripts, effectively doubling the ompA mRNA level (8, 28). These data suggest that a regulatory mechanism is superimposed on this gene cluster that is shared with late stage III-regulated genes, and thus basal-level transcription is strongly upregulated at 24 hpi. Fourteen genes fall into the this cluster, including ompA, ompB, glgA glycogen synthase, clpC protease, a predicted disulfide bond isomerase (CT783), and yscC, a major outer membrane structural component of the type III secretion system.

Taken together, the functions encoded by the genes assigned to the midlate I and midlate II clusters demonstrate that stage II gene transcription represents a massive regulatory switch. The transcriptional profile and annotated functions (27) of the genes within the two stage II clusters suggest that they serve a crucial biological role in the early stages of RB to EB transition, including the initiation of DNA condensation, an event that precedes outer membrane reorganization.

Stage III.

In contrast to midlate II transcripts, which are upregulated by 18 hpi (e.g., ompA), genes whose transcripts were not optimally expressed until 24 hpi and were then expressed at similar levels at 36 hpi constitute stage III. Given that these genes reach a threshold level of expression late in the developmental cycle, one may imagine that relatively few genes would be assigned to this class; however, 70 genes (≈10% of the genome) fell into this temporal category.

Stage III consists of two temporal clusters, late and very late. The late cluster displays relatively similar negative change values for 6, 12, and 18 hpi. Hence, transcription of these genes is not significantly induced until 24 hpi (Table 1). This class of genes is typified by omcA and omcB; expressed only late in the developmental cycle, they encode two cysteine-rich membrane proteins found only in EB (13). In addition to outer membrane changes, EB are characterized by marked DNA condensation late in development (6). A unique DNA topoisomerase fused to an SWIB domain (CT643), a DNA gyrase A paralogue (CT660), and histone-like protein 2 (hctB) are also induced at this stage and are implicated in the mechanism of the terminal stages of condensed nucleoid formation.

The largest functional category, accounting for 31 of the 69 genes within this cluster, is the hypothetical protein group consisting of genes of unknown function unique to chlamydiae (27). The coordinate regulation of these genes suggests that they play essential functions in EB formation. A chlamydial orthologue of a regulator of type III secretion, lcrH, is also transcribed at stage III, suggesting that the gene product of lcrH is produced to arm chlamydial EB for sensing interaction with host cells. Despite the large number of genes in stage III, only one gene involved in transcriptional regulation was identified (hrcA) in the late cluster, temporally linking this gene with the global regulation of late gene expression in chlamydiae.

The temporal cluster designated very late is defined by an expression profile consisting of transcripts detected in greater abundance at 36 hpi than at 24 hpi (Table 1). At 36 hpi there is a mixed population of RB and EB, with the majority of the forms present being transcriptionally inactive EB. Nevertheless, six genes had significantly greater transcript abundance at 36 than at 24 hpi. The transcripts of only two genes in this cluster, CT147 and CT249, were first detected above threshold levels at 36 hpi, while the others were initially induced at either 18 or 24 hpi but continued to increase significantly at 36 hpi. All of the genes in this cluster encode Chlamydia-specific proteins of undetermined function (27).

Developmental regulation of functionally related genes.

The developmental cycle of chlamydiae is principally mediated at the transcriptional level, and the identification of a developmentally regulated transcription factor (Fig. 2A), several cellular proteases, and signal transduction factors implicates defining roles for these transcripts. Superimposed on the functions of these transcription factors is a role for a number of stage III genes, including the chlamydial histone-like proteins (4) and eukaryotic-type chromatin factors (27), that likely mediate compaction of the chlamydial chromosome, which occurs during EB morphogenesis. Previous studies have demonstrated that promoter recognition in chlamydiae is dependent upon DNA structure (17), and thus it is likely that such genes have regulatory functions.

FIG. 2.

Expression profiles of functionally related sets of genes. Transcription mediators (A), type III secretion apparatus proteins (B), gluconeogenesis/tricarboxylic acid cycle (C), and membrane proteins/DNA compaction proteins (D) are clustered together as functional groups, reflecting temporal hierarchy within each functional group. Functional groups are based on chlamydial genome project designations (27). Expression profiles of genes are in rows, with temporal progression from left to right. Expression profiles were clustered with Cluster software and plotted with Treeview software. Expression levels are color coded as in Fig. 1.

The identification of clusters of cotranscribed genes and development stage-specific gene expression patterns have important implications for the characterization of chlamydial developmental biology, biological processes inferred from the chlamydial genome, and pathogenesis. Inclusion membrane proteins (Inc) are likely secreted by the type III secretion system into the mammalian host cell vacuole containing chlamydiae (Fig. 2B) (29). Although numerous inc genes have been identified (2), all were constitutively transcribed, with the notable exception of incC, a member of the early gene cluster in stage I. incB and incC have been reported to be expressed as an operon in Chlamydia psittaci (3). If these genes are organized as an operon in C. trachomatis, one would expect similar gene expression profiles; however, incB did not reach the threshold for the early gene cluster. Potential reasons for different profiles in linked genes may be due to variations in (i) mRNA processing (7), (ii) mRNA degradation (10), (iii) statistical variation, or (iv) additional regulatory mechanisms. Thus, an important advantage of using a microarray experimental approach is that it tests each gene, regardless of chromosomal arrangement.

The overall chlamydial metabolic strategy, reflected by transcription profiling for the initial 12 hpi, is the expression of genes involved with transcription, translation, standard protein secretion, ATP and GTP translocases, adenylate and guanylate kinases, and the DNA replication machinery. Moreover, about half of all the transporters, especially those for broadly specific amino acid transport and predicted glutamate transport, are expressed during the initial 12 hpi, representing stage I.

A major metabolic shift occurs between 12 and18 hpi, when polysaccharide and glutamine transporters are in place and chlamydial energy metabolic systems are initiated, including the chlamydial tricarboxylic acid cycle genes and oxidoreductases, and the glycolysis and gluconeogenesis pathways are completed (Fig. 2C). These findings are consistent with those reported by Iliffe-Lee and McClarty (14). The C. trachomatis genome contains all of the genes required for glycogen synthesis and degradation (27). It is thought that glycogen could serve to sequester glucose from the host cell or provide energy for early differentiation (19). Glycogen hydrolase (glgX) and glucosyl transferase (glgB) are both transcribed within 6 hpi, while glycogen synthase (glgA) and glycogen branching enzyme (glgC) are each strongly upregulated by 24 hpi. The late gene transcription and ≈30-fold increase in glycogen synthase activity from 12 to 24 hpi is consistent with the large quantity of glycogen known to be produced by C. trachomatis during the late stages of infection (5).

Base and nucleotide metabolism salvage systems, lipopolysaccharide, fatty acid/phospholipid biosynthetic enzymes, and protein folding and modification systems are also differentially expressed between 12 and 24 hpi. Another major expression pattern shift occurs between 24 and 36 hpi, a period in the developmental cycle that is dominated by the expression of outer membrane proteins, a disulfide bond isomerase (CT783), and DNA compaction-related proteins (Fig. 2D), all of which function to complete the terminal stages of RB to EB conversion. Also expressed at this time, and thus implicated in EB maturation, are many Chlamydia-specific proteins of unknown function.

The majority of the type III secretion genes were also abruptly upregulated by 18 hpi with little transcription at 6 or 12 hpi except for the late stage III transcription of lcrH and yscC (Fig. 2B). These data support the hypothesis that the type III secretion apparatus is assembled relatively late in the developmental cycle and likely arms infectious EB to prepare them to engage their target host cells.

Validation of microarray results by RT-PCR.

To confirm the microarray data, the expression of several genes from each category was determined by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) with total RNA isolated from C. trachomatis-infected cells. RT-PCR of this gene set provided data consistent with the quantitative measures by microarray (Fig. 3). Because RT-PCR utilizes total RNA isolated from infected cells, these data also demonstrated that the RNA isolation procedure used for the microarray analysis did not systematically bias the results. Comparison of the RT-PCR and microarray data illustrates important technical differences. Whereas the strength of RT-PCR is its sensitivity and ability to determine the onset of gene transcription, DNA microarrays have the ability to determine changes in transcriptional activity from a basal level in parallel for a large number of genes. This basal level could be low or high.

FIG. 3.

Temporal expression of C. trachomatis L2 genes representing constitutive, early, midlate I, midlate II, and very late cluster categories assessed by RT-PCR. Total RNA extracted from C. trachomatis L2-infected L929 cells was tested by RT-PCR, and each lane contains the DNA product for each time point postinfection. ORF numbers and names listed in the left column are based on those of Stephens et al. (27). The developmental stages to which each of the transcripts was categorized are listed in the right column.

Concluding remarks.

DNA microarray analysis of chlamydial development stage-specific transcription was evaluated by comparing global gene expression profiles at various time points throughout the developmental cycle. The time points selected, 6, 12, 18, 24, and 36 hpi, represent times associated with phenotypic changes, from early to late, which are known to occur (12). As microarray analysis measures RNA present in a population of relatively asynchronous organisms, there is inherently a relative continuum of gene expression. However, the use of a high (threefold) change for this analysis revealed abrupt or prominent shifts in gene expression.

Thus far, expression profiling in chlamydiae as well as other obligate intracellular organisms has been limited to RT-PCR-based approaches. In a report by Shaw et al. (25), RT-PCR analysis was used to characterize the onset of transcription of several developmentally expressed genes. There are no major differences between the subset of expression data reported by Shaw et al. (25) and the microarray data reported here that cannot be attributed to the different technical capabilities of RT-PCR and DNA microarrays.

Distinct morphological changes which occur at specific times during the chlamydial developmental cycle have been described for over 30 years (18), but the molecular basis for these phenotypic changes is unknown. By microarray analysis, the C. trachomatis transcriptome was characterized at five critical time points during the process of its developmental cycle. The results provide a comprehensive, genome-wide portrait of genes that accompany, and thus likely mediate, these morphological alterations.

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Brunelle for technical assistance involving the chlamydial DNA arrays and H. Gilbert for valuable assistance in the RT-PCR analysis. We also thank D. Schnappinger and M. I. Voskuil for helpful discussions and C. Lammel for critical comments during the preparation of the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI42156 and AI32943. T. L. Nicholson is the recipient of National Research Service Award AI50361.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arfin, S. M., A. D. Long, E. T. Ito, L. Tolleri, M. M. Riehle, E. S. Paegle, and G. W. Hatfield. 2000. Global gene expression profiling in Escherichia coli K-12. The effects of integration host factor. J. Biol. Chem. 275:29672-29684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bannantine, J. P., R. S. Griffiths, W. Viratyosin, W. J. Brown, and D. D. Rockey. 2000. A secondary structure motif predictive of protein localization to the chlamydial inclusion membrane. Cell. Microbiol. 2:35-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bannantine, J. P., D. D. Rockey, and T. Hackstadt. 1998. Tandem genes of Chlamydia psittaci that encode proteins localized to the inclusion membrane. Mol. Microbiol. 28:1017-1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barry, C. E., 3rd, S. F. Hayes, and T. Hackstadt. 1992. Nucleoid condensation in Escherichia coli that express a chlamydial histone homolog. Science 256:377-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiappino, M. L., C. Dawson, J. Schachter, and B. A. Nichols. 1995. Cytochemical localization of glycogen in Chlamydia trachomatis inclusions. J. Bacteriol. 177:5358-5363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costerton, J. W., L. Poffenroth, J. C. Wilt, and N. Kordova. 1976. Ultrastructural studies of the nucleoids of the pleomorphic forms of Chlamydia psittaci 6BC: a comparison with bacteria. Can. J. Microbiol. 22:16-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Douglas, A. L., and T. P. Hatch. 1995. Functional analysis of the major outer membrane protein gene promoters of Chlamydia trachomatis. J. Bacteriol. 177:6286-6289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fahr, M. J., A. L. Douglas, W. Xia, and T. P. Hatch. 1995. Characterization of late gene promoters of Chlamydia trachomatis. J. Bacteriol. 177:4252-4260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fawcett, P., P. Eichenberger, R. Losick, and P. Youngman. 2000. The transcriptional profile of early to middle sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. United States 97:8063-8068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grunberg-Manago, M. 1999. Messenger RNA stability and its role in control of gene expression in bacteria and phages. Annu. Rev. Genet. 33:193-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hackstadt, T., W. Baehr, and Y. Ying. 1991. Chlamydia trachomatis developmentally regulated protein is homologous to eukaryotic histone H1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. United States 88:3937-3941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hatch, T. P. 1999. Cell biology, p. 101-138. In R. S. Stephens (ed.), Chlamydia: intracellular biology, pathogenesis, and immunity. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 13.Hatch, T. P., M. Miceli, and J. E. Sublett. 1986. Synthesis of disulfide-bonded outer membrane proteins during the developmental cycle of Chlamydia psittaci and Chlamydia trachomatis. J. Bacteriol. 165:379-385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iliffe-Lee, E. R., and G. McClarty. 1999. Glucose metabolism in Chlamydia trachomatis: the ′energy parasite' hypothesis revisited. Mol. Microbiol. 33:177-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koehler, J. E., R. R. Burgess, N. E. Thompson, and R. S. Stephens. 1990. Chlamydia trachomatis RNA polymerase major sigma subunit. Sequence and structural comparison of conserved and unique regions with Escherichia coli sigma 70 and Bacillus subtilis sigma 43. J. Biol. Chem. 265:13206-13214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laub, M. T., H. H. McAdams, T. Feldblyum, C. M. Fraser, and L. Shapiro. 2000. Global analysis of the genetic network controlling a bacterial cell cycle. Science 290:2144-2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mathews, S. A., and R. S. Stephens. 1999. DNA structure and novel amino and carboxyl termini of the Chlamydia sigma 70 analogue modulate promoter recognition. Microbiology 145:1671-1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsumoto, A., and G. P. Manire. 1970. Electron microscopic observations on the effects of penicillin on the morphology of Chlamydia psittaci. J. Bacteriol. 101:278-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McClarty, G. 1999. Chlamydial metabolism as inferred from the complete genome sequence, p. 69-100. In R. S. Stephens (ed.), Chlamydia: intracellular biology, pathogenesis, and immunity. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 20.Pace, N. R. 1997. A molecular view of microbial diversity and the biosphere. Science 276:734-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perara, E., D. Ganem, and J. N. Engel. 1992. A developmentally regulated chlamydial gene with apparent homology to eukaryotic histone H1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:2125-2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schachter, J. 1999. Infection and disease epidemiology, p. 139-169. In R. S. Stephens (ed.), Chlamydia: intracellular biology, pathogenesis, and immunity. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 23.Scidmore, M. A., E. R. Fischer, and T. Hackstadt. 1996. Sphingolipids and glycoproteins are differentially trafficked to the Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion. J. Cell Biol. 134:363-374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sekowska, A., S. Robin, J. J. Daudin, A. Henaut, and A. Danchin. 2001. Extracting biological information from DNA arrays: an unexpected link between arginine and methionine metabolism in Bacillus subtilis. Genome Biol. 2:research0019.1-0019.12. [Online.] http://genomebiology.com/2001/2/6/RESEARCH/0019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Shaw, E. I., C. A. Dooley, E. R. Fischer, M. A. Scidmore, K. A. Fields, and T. Hackstadt. 2000. Three temporal classes of gene expression during the Chlamydia trachomatis developmental cycle. Mol. Microbiol. 37:913-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stamm, W. E. 1999. Chlamydia trachomatis infections: progress and problems. J. Infect. Dis. 179(Suppl. 2):S380-S383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stephens, R. S., S. Kalman, C. Lammel, J. Fan, R. Marathe, L. Aravind, W. Mitchell, L. Olinger, R. L. Tatusov, Q. Zhao, E. V. Koonin, and R. W. Davis. 1998. Genome sequence of an obligate intracellular pathogen of humans, Chlamydia trachomatis. Science 282:754-759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stephens, R. S., E. A. Wagar, and U. Edman. 1988. Developmental regulation of tandem promoters for the major outer membrane protein gene of Chlamydia trachomatis. J. Bacteriol. 170:744-750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Subtil, A., C. Parsot, and A. Dautry-Varsat. 2001. Secretion of predicted Inc proteins of Chlamydia pneumoniae by a heterologous type III machinery. Mol. Microbiol. 39:792-800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wichlan, D. G., and T. P. Hatch. 1993. Identification of an early-stage gene of Chlamydia psittaci 6BC. J. Bacteriol. 175:2936-2942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]