Abstract

Transcription of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I genes is regulated by both tissue-specific (basal) and hormone/cytokine (activated) mechanisms. Although promoter-proximal regulatory elements have been characterized extensively, the role of the core promoter in mediating regulation has been largely undefined. We report here that the class I core promoter consists of distinct elements that are differentially utilized in basal and activated transcription pathways. These pathways recruit distinct transcription factor complexes to the core promoter elements and target distinct transcription initiation sites. Class I transcription initiates at four major sites within the core promoter and is clustered in two distinct regions: “upstream” (−14 and −18) and “downstream” (+12 and +1). Basal transcription initiates predominantly from the upstream start site region and is completely dependent upon the general transcription factor TAF1 (TAFII250). Activated transcription initiates predominantly from the downstream region and is TAF1 (TAFII250) independent. USF1 augments transcription initiating through the upstream start sites and is dependent on TAF1 (TAFII250), a finding consistent with its role in regulating basal class I transcription. In contrast, transcription activated by the interferon mediator CIITA is independent of TAF1 (TAFII250) and focuses initiation on the downstream start sites. Thus, basal and activated transcriptions of an MHC class I gene target distinct core promoter domains, nucleate distinct transcription initiation complexes and initiate at distinct sites within the promoter. We propose that transcription initiation at the core promoter is a dynamic process in which the mechanisms of core promoter function differ depending on the cellular environment.

Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I genes, like most typical housekeeping genes, are constitutively active in all tissues. However, unlike housekeeping genes, the relative levels of class I expression vary dramatically among different tissues. The highest levels of expression occur in tissues and cells of the immune system; the lowest levels are observed in the nervous system and germ line cells (18, 33, 51). Thus, although the class I promoter is thought to be constitutively accessible to the general transcription machinery, it is also subject to diverse tissue-specific regulatory influences. Together, the constitutive and tissue-specific regulatory mechanisms determine the basal level of class I expression in any tissue at any given time.

MHC class I expression is also dynamically modulated in the presence of certain cytokines, hormones, and other inflammatory agents. For example, interferon (IFN) increases class I transcription, whereas thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) represses it (11, 17, 52). Thus, class I expression is regulated by two distinct pathways. The basal pathway regulates homeostatic expression and establishes the tissue-specific “set-point” level of class I expression in any given tissue. In contrast, the modulated pathways dynamically regulate, either specifically activating (activated pathway) or repressing (repressed pathway), class I expression in response to transiently expressed cytokines and hormones.

The upstream DNA elements regulating basal and modulated expression of the MHC class I gene, PD1, have been intensively investigated. All regulatory elements necessary to confer normal patterns of class I expression are contained within about 1 kb upstream of the coding sequence (14, 50). Distinct domains regulate basal transcription and dynamically activated transcription: one that is located between −800 and −700 bp is responsible for tissue-specific expression, and another one located between −500 and −50 bp is responsible for both activated and basal expression (23, 25, 37, 41, 64). Among the elements that regulate basal class I expression is a canonical E-box (at positions −314 to −309) recognized by the transcription factor USF (23). USF consists of two family members, USF1 and USF2 (23, 54). Both are ubiquitously expressed; their expression is not known to be altered by hormone/cytokine stimulation, and therefore they are considered to contribute to basal class I expression.

The modulatory domain contains both elements that support basal expression and dynamically modulated class I transcription in response to cytokines, hormones, and inflammatory agents. Examples of the latter include enhancer A (enh A), an IFN-stimulated response element, and a composite RF-X/cyclic AMP response element (CRE) that modulate class I expression by binding inducible trans-acting factors (2, 11, 18, 19, 50, 59). The CRE mediates both induction of transcription by gamma IFN (IFN-γ) and repression by TSH (43, 52).

The IFN-γ mediator, CIITA, is a non-DNA-binding coactivator that interacts with constitutively expressed RF-X and ATF trans-acting factors already bound at the RF-X/CRE site (27, 42). CIITA contributes to class I expression in B lymphocytes, dendritic cells, and macrophages, cell types in which CIITA is constitutively expressed. In addition, IFN-γ induces CIITA in many other cell types, resulting in their activated class I expression (20, 38, 43).

MHC class I gene expression depends upon the proper integration of regulatory signals from these upstream domains with the appropriate general transcription machinery at the core promoter. However, a detailed analysis of the MHC class I core promoter and its contribution to these diverse regulatory pathways is lacking. The present study was undertaken to begin to characterize the core promoter and define the mechanism(s) by which the basal and activated pathways are integrated at the MHC class I core promoter to achieve appropriate levels of transcription.

The core promoter is defined as the minimal length of DNA sufficient to direct accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase (Pol) II (9). Thus, the core promoter region regulates three fundamental steps in transcription. First, it provides a docking site for general transcription factors (GTFs) capable of recruiting RNA Pol II and associated factors required for basal transcription. Second, through the assembled GTFs and RNA Pol II, it serves as a molecular platform to integrate regulatory signals delivered by upstream silencer and enhancer elements to appropriately adjust the level of promoter activity. Third, a core promoter determines the start site(s) of transcription (3, 16, 21, 44, 45, 55, 60).

Analysis of a number of cellular and viral promoters has led to the identification of a small number of core promoter elements. The two most common and best-characterized core promoter elements are the TATAA box and Inr motifs. The TATAA box is an A/T-rich sequence located about 30 bases upstream of initiation (7). The Inr is a pyrimidine-rich element that generally spans the site of transcript initiation (29, 30, 36, 56, 57, 65). Consensus sequences for both TATAA and Inr elements have been defined, although considerable sequence variation occurs among promoters (36, 53). Different core promoters may contain one, both, or neither element. For example, whereas the TdT promoter has only an Inr (56), the AdML has both TATAA and Inr motifs (1). In Drosophila melanogaster, a recent analysis found an equal distribution of these various structures (31). Additional elements, including a TFIIB recognition element (BRE) and a downstream promoter element (DPE), are also found in many core promoter regions (5, 6, 9, 32). Surprisingly, many promoters do not have a recognizable homolog of any of these elements, suggesting that additional promoter elements remain to be identified (31). A number of such promoters, many of them regulating housekeeping genes, are located within CpG islands (15).

In contrast to the modulatory and tissue-specific domains, the class I core promoter region is relatively less characterized. By sequence homology, three elements are identified in the class I core promoter region: TATAA- and Inr-like motifs and a CA/GT-rich region (S-box). The S-box sequence is homologous to those recognized by the Sp1 family of transcription factors in other promoters (10, 13, 35). The relative functional importance of these elements in MHC class I transcription has not been established. Nor has the site(s) of transcription initiation been determined.

Here we report that the class I core promoter is a complex structure, in which no single element subserves all transcription functions. Rather, basal and activated transcription target distinct regions of the core promoter and have distinct core promoter element requirements. Transcription initiates at multiple sites, within two general domains: basal transcription initiates largely upstream of −6 bp, whereas activated transcription predominantly initiates downstream of −6. Furthermore, basal transcription is dependent upon Sp1 binding to the CA/GT-rich region of the S-box. In contrast, activated transcription is neither dependent upon the CA/GT rich region nor Sp1 binding. Basal and activated transcription also differ in their requirement for a TAF1 (TAFII250)-containing initiation complex. Thus, basal and activated modes of class I transcription represent distinct molecular pathways that engage different components of the core promoter. These findings suggest that the complex structure of the MHC class I core promoter allows it to uniquely integrate cell type and/or dynamic upstream regulatory signals to direct appropriate levels of transcription.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and cultivation.

The HeLa epithelial, baby hamster kidney (BHK) and tsBN462 cell lines were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagles medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.2), and gentamicin sulfate (10 μg/ml). Jurkat (T-cell) and M12 (B cell) lines were grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 55 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 100 μM minimal essential amino acids, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.2), and gentamicin sulfate (10 μg/ml). Cell lines were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C in 7% CO2, except tsBN462 which were maintained at 32°C in 7% CO2.

Plasmids and cloning strategies.

The MHC class I promoter used in these studies derived from the swine class I gene, PD1 (14, 49). The PD1 promoter truncation series, ligated to the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) reporter, was previously described (24, 25). To generate −50CAT, −313CAT was digested with NarI and NdeI (New England Biolabs), followed by Klenow fill-in and blunt-end ligation. The NarI site is at position −50 within the class I promoter, and the NdeI site is located immediately 5′ of the class I promoter sequences in the CAT reporter. The class I promoter sequences, extending from the 5′ XbaI site to the HindIII at position +1, were excised from the CAT 5′ truncation series and were ligated into the NheI/HindIII sites in the multiple cloning region of the pGL2B luciferase expression vector. Synthetic double-stranded oligonucleotides were inserted into the HindIII site of pSV0CAT to generate the InrWT core promoter and derivative mutant reporter constructs (24). The sense strand sequences of the oligonucleotides synthesized (from −30 to +14) are illustrated in Fig. 4A. The NarI/NcoI promoter fragments of the Inr core promoter series were subsequently cloned into NarI/NcoI digested −416CAT to generate the −416Inr series. The NarI site is at position −50 within the class I promoter, and the NcoI site is located within the CAT coding region. The mammalian expression vector Flag-CIITA wild type (WT) has been previously described (43); CIITA WT was cloned into the baculovirus transfer vector PVL1293 at the EcoRI site.

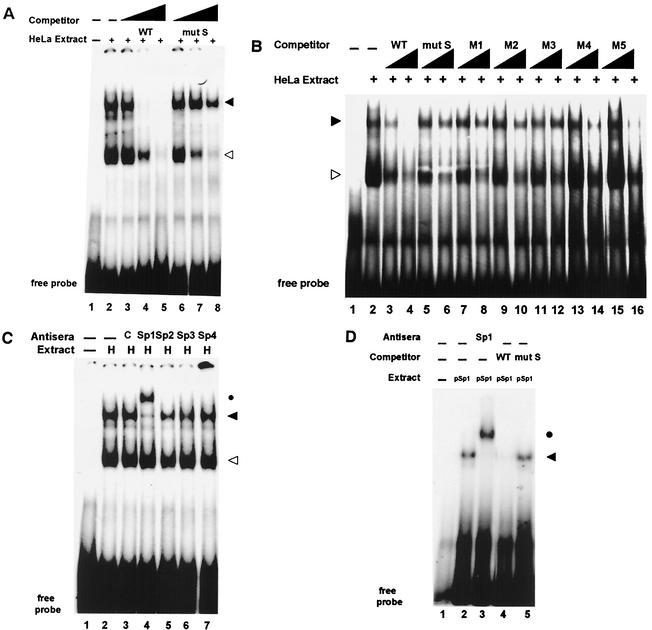

FIG. 4.

The transcription factor Sp1 binds CA/GT-rich S-box element. (A) Gel shift analysis by using the class I core promoter region (−50 to +14), shown in Fig. 2A, as a probe to identify specific core promoter binding complexes. Lane 1 contains probe alone in the absence of HeLa extract. Lane 2 shows two complexes formed in the presence of HeLa extract, indicated by the arrowheads. Lanes 3 to 5 and lanes 6 to 8 represent increasing (102-, 103-, and 104-fold) amounts of unlabeled WT or mut S oligonucleotide competitors, respectively. The solid arrowhead indicates the S-box specific complex; the open arrowhead indicates a nonspecific single-strand binding complex. (B) Mapping the specific S-box binding complex by using the M1 to M5 panel of mutant oligonucleotides detailed in Fig. 3B. Lane 1 contains the core promoter probe in the absence of HeLa extract. Lane 2 shows the two complexes formed in the presence of HeLa extract, indicated by the arrowheads. Lanes 3 and 4 and lanes 5 and 6 represent increasing unlabeled WT or mut S oligonucleotide competitors, respectively. Increasing unlabeled, mutant oligonucleotide competitors, M1 to M5, are shown in lanes 7 to 16, respectively. The S-box-specific complex is indicated by the solid arrowhead. (C) Antibody supershift analysis of the specific S-box binding complex. Lane 1 contains core promoter (−50 to +14) probe in the absence of HeLa extract. Lane 2 contains complexes formed in the presence of HeLa extract, indicated by the arrowheads; the solid arrowhead is the S-box-specific complex. Lane 3 contains control antisera; lanes 4 to 7 contain antisera specific for Sp1, Sp2, Sp3, and Sp4, respectively. The supershifted complex, in the presence of anti-Sp1 antisera, is indicated by the solid circle. (D) Purified Sp1 protein (pSp1) binds to the S-box region of the core promoter. Lane 1 contains probe alone. Lane 2 contains the complex formed in the presence of pSp1, indicated by the solid arrowhead. Lane 3 contains specific anti-Sp1 antiserum against Sp1; the supershifted complex is indicated by the solid circle. Lanes 4 and 5 contain WT and mut S unlabeled competitor oligonucleotides, respectively.

Transfections.

Transient transfections were performed by using a constant amount of DNA (5 μg). At 24 h prior to transfection 106 HeLa or BHK cells were seeded in 100-mm tissue culture dishes. Transfections utilized standard calcium phosphate precipitation as previously described (25). The medium was replaced 24 h after transfection with fresh medium, and cells were harvested after an additional 24 h. Temperature-sensitive tsBN462 cells were left at 32°C for 24 h after transfection and then shifted to 39°C (restrictive temperature) or left at 32°C (permissive temperature) for an additional 24 h (63). HeLa cells and L cells were maintained at 37°C for 48 h after transfection. Reporter activity was corrected by cotransfecting an internal control plasmid control, either pSV2LUC (200 ng) or CMV-β-Gal (50 ng). Jurkat and M12 lymphocytes were transfected by electroporation (250 V, 975 μF) by using Bio-Rad gene pulser II electroporator. All CAT enzyme assays were measured in the linear range; control 14C-labeled chloramphenicol values ranged between 20 and 80% among the different experiments. Luciferase and β-galactosidase determinations were made by using a Monolight 2010 luminometer (Analytical Luminescence Laboratory).

Preparation of recombinant CIITA protein.

Flag-CIITA WT or the mutants were expressed in Sf9 cells by using baculovirus-mediated transfection according to the manufacturer's protocol (using the Pharmingen kit). Recombinant Flag-CIITA (rCIITA) was immunoprecipitated by using anti-Flag M2 agarose beads (Sigma) and eluted with 100 μg of Flag peptide/ml (43).

Isolation of RNA and 5′RACE.

The PD1 transgenic mouse strain used for in vivo start site analysis, CAT.516, was previously described (37). The PD1, stably transfected, murine L-cell line, 93B2, was previously described (49). Total RNA from transgenic spleen or 93B2 cell line was isolated by using RNA STAT-60 (Tel-Test, Inc.). Transcription start sites, utilized by transgenic splenocytes, were determined by using the SMART RACE (rapid amplification of cDNA ends) cDNA amplification kit (Clontech) with 1 mg of total splenic RNA; RACE-Ready cDNA was subsequently PCR amplified by using the SMARTII and CAT gene-specific primers (GGTGGTATATCCAGTGATTTTTTTCTCCAT). Amplified products were cloned into the TA cloning vector (Invitrogen) and used to transform DH5α competent bacteria (Invitrogen). Ampicillin-resistant colonies were screened for the presence of the CAT sequence by using the CAT primer. DNA prepared from positive colonies was sequenced by using the ABI Prism dye terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction kit (Perkin-Elmer). Analysis of in vivo start sites utilized in the 93B2 PD1 stably transfected L-cell line was done by primer extension as previously described (62).

In vitro transcription and coupled primer extension.

In vitro transcription reaction mixtures contained 2 μg of class I CAT reporter construct, 6 mM MgCl2, 0.8 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, and 30 U of HeLa nuclear extract (Promega) in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 100 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, and 20% glycerol in a total of 25 μl was incubated at 20°C for 60 min. Analysis of the in vitro-transcribed RNA was done by primer extension as previously described (62).

RESULTS

A minimal MHC class I core promoter is transcriptionally active in vivo.

To determine the functional boundaries of the class I promoter, we compared the activity of an extended −416WT class I promoter construct that terminates at −416 bp and contains a series of upstream enhancer elements with the promoter-proximal −50WT construct, truncated at −50 bp. Both promoter segments have a common 3′ terminus at +14 and were ligated to a CAT reporter (Fig. 1A). The constructs were transiently transfected into HeLa epithelial cells, and their activities were compared. Surprisingly, −50WT retained promoter activity that was significantly higher than the promoter-less control (pSVO) and was less than twofold reduced compared to −416WT (Fig. 1A). Similar results were obtained when a luciferase reporter was substituted for the CAT reporter gene (data not shown). These data indicate that the class I core promoter is contained within a 64-bp segment, between bp −50 and bp +14, and remains active in the absence of upstream elements.

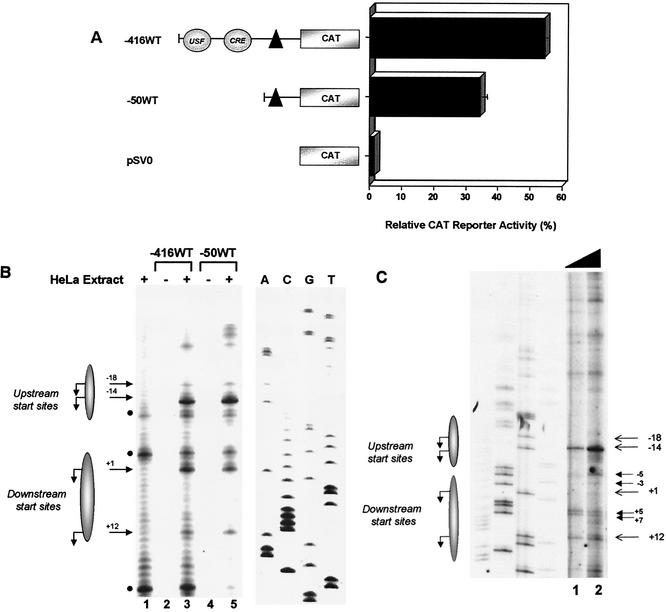

FIG. 1.

Identification of a minimal MHC class I core promoter region. (A) HeLa cells were transiently transfected with MHC class I promoter constructs −416WT, −50WT, and promoterless pSV0. The −50WT extends upstream from positions +14 to −50, whereas −416WT extends upstream from positions +14 to −416 and contains USF and CRE regulatory elements. Class I promoter and pSV0 control constructs, diagrammed on the left, are all ligated to the CAT reporter. Data are expressed as relative percentages of acetylation corrected to an internal transfection control, pSV2LUC. The black triangle represents the core promoter region. Error bars indicate the standard error. (B) In vitro transcriptional start sites utilized by −416WT and −50WT constructs were determined by primer extension of in vitro-transcribed RNA. HeLa extract alone control is shown in the lane 1. Background bands present in the HeLa extract alone control are indicated by solid black circles. DNA-only controls for −416WT and −50WT are shown in lanes 2 and 4, respectively. The arrows along the left indicate specific transcriptional start sites in lanes 3 and 5, in the presence of HeLa nuclear extract. Shaded ellipses representing upstream and downstream transcription start site regions (where the major start sites, indicated by arrows, were observed to originate) are provided on the left for orientation. The scan encompasses the length of the −50WT class I sequences. A sequence ladder for the class I promoter used in these studies (shown on the right) was generated by using the same primer used in primer extension analysis of in vitro-synthesized RNA and was used to determine the precise start sites. Minor start sites were also inconsistently observed at other sites upon longer exposure. (C) RNA was prepared from a fibroblast cell line (93B2) containing a stably integrated PD1 MHC class I gene. Increasing amounts of total RNA, 3 and 10 μg (lanes 1 and 2) were analyzed by primer extension to determine start site utilization in vivo. Shadowed ellipses representing the upstream and downstream transcription regions where the major start sites originate in in vitro transcription (indicated by arrows) are provided on the left for orientation. The −3 and −5 start sites, observed in vivo with 93B2 RNA, would have been obscured by a nonspecific band generated by HeLa nuclear extract in in vitro transcription reactions (see Fig. 1B). A sequence ladder of the class I promoter is also included.

MHC class I transcription initiates at multiple start sites.

The studies described above demonstrate that the MHC class I core promoter, unlike most described core promoters, is transcriptionally active. To determine that the core promoter initiates transcription properly, the transcript initiation profile generated by the minimal promoter construct (−50WT) was compared to that of the extended WT class I promoter (−416WT) in in vitro transcription assays with HeLa nuclear extract. With either template, a spectrum of transcripts was observed initiating from two distinct regions within the core promoter (Fig. 1B, shadowed ellipses): an upstream region defined by the A−18 and A−14 start sites, and a downstream region defined by the A+1 and A+12 start sites (Fig. 1B, lanes 3 and 5). These start sites were not observed in controls containing either HeLa nuclear extract alone (Fig. 1B, lane 1) or MHC class I promoter DNA template in the absence of HeLa nuclear extract (Fig. 1B, lanes 2 and 4). In the presence of 10 μg of α-amanitin/ml, class I transcripts are inhibited by >70%, indicating that these are RNA Pol II-derived transcripts (data not shown). These data indicate that MHC class I transcripts can initiate at multiple sites in the core promoter region. Furthermore, the same pattern was observed in both the extended −416WT and core promoter −50WT class I constructs. Thus, the absence of upstream sequences does not alter transcription initiation sites from the core promoter. Further, under these conditions of in vitro basal transcription, the A−14 site was the most frequently utilized site.

To verify that the transcription initiation sites observed in in vitro transcription reflected in vivo usage, we examined start site usage in a murine fibroblast cell line containing a stably integrated full-length MHC class I gene, PD1, that has been shown to direct normal expression of class I in transgenic mice (14, 49). Primer extension analysis of RNA derived from this cell line also revealed multiple initiation sites, a finding consistent with the in vitro transcription data. As observed in in vitro transcription, the dominant start site was at the A−14 position, with additional weaker sites at positions −18, +1, and +12. In addition, weak initiation sites mapped to positions −3, −5, +5, and +7 that were not routinely observed in vitro (Fig. 1C). In murine fibroblasts and in vitro in HeLa nuclear extract—both conditions of largely basal transcription—transcription initiation from the bp −14 site predominates. Taken together, these data indicate that both in vivo and in vitro, transcription initiates within the core promoter but at multiple sites. These findings demonstrate that (i) in vitro transcription does not generate aberrant initiation sites and (ii) DNA sequences outside of the core promoter (bp −50 to +14) do not detectably contribute to the pattern of basal transcription initiation.

Mutational analysis of the class I core promoter region.

The sequence of the 64-bp class I core promoter is shown in Fig. 2A. To define the constituent DNA sequence element(s) required for core promoter function, we generated constructs containing mutations spanning the core promoter (Fig. 2A, mutated sequences are listed underneath each sequence) and determined their effects on transcription initiation in vitro and promoter activity in vivo.

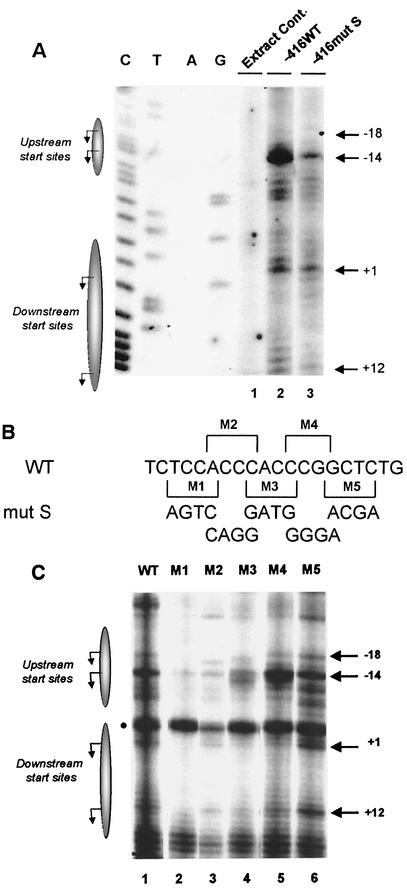

FIG. 2.

Role of core promoter sequences in determining start site usage. (A) The minimal MHC class I core promoter sequence from bp −50 to +14 is shown. The TATAA- and Inr-like sequences are underlined, and the S-box containing the CA/GT-rich element is within the dotted box. Major transcription start sites (determined in Fig. 1B) are indicated by the arrows. Core promoter mutations introduced into the −416 construct, mut T, mut I, and mut S are shown at the bottom and are aligned as they appear in the mutant core promoter constructs. (B) Primer extension analysis to examine in vitro transcriptional start site utilization by −416mut T and mut I. HeLa extract alone control is shown in the lane 1. Background bands are indicated by black solid circles. DNA-only controls for −416WT, −416mut T, and −416mut I are shown in lanes 2, 4, and 6, respectively. Specific, transcriptional start sites (in lanes 3, 5, and 7) in the presence of HeLa extract are indicated by the arrows. Shaded ellipses representing the upstream and downstream transcription regions are provided for orientation. A sequence ladder of the class I promoter is also included.

Two of the mutations, mut T (bp −30 to −26) and mut I (bp −3 to +7), encompassed sequences of the core promoter with homology to known promoter elements: the 5′ TCTAA sequence is orthologous to the TATAA box of the mouse class I genes, whereas the 3′ CTCAGCTT sequence is homologous to a consensus Inr sequence. Both mut T and mut I supported transcription and used the same initiation sites as the WT promoter in vitro (Fig. 2B). However, the relative usage of these in vitro transcription start sites differed. Most notable was a consistent reduction in the usage of A−18, A+1, and A+12 start sites relative to A−14 observed with mut T (Fig. 2B, compare lanes 3 and 5). This difference was observed regardless of the extent of 5′ upstream sequences (data not shown). In contrast, the frequency of start sites utilized by mut I was indistinguishable from that of the WT core promoter (Fig. 2B, compare lanes 3 and 7). [The increase in the mut I A+12 start site, seen in Fig. 2B, was not routinely observed.] Neither mut T nor mut I affected transcript initiation at the −14 start site (Fig. 2B, compare lanes 3, 5, and 7). Mutations upstream of bp −30 had no effect on promoter activity (data not shown). Taken together, these results extend our previous observations (24, 63) and suggest that sequences between bp −50 and −26 and sequences between bp −3 and +7 are not essential for basal class I transcription. Rather, they appear to modulate start site selection.

To examine the contributions of these elements to in vivo promoter activity, WT and mutant −416 constructs were transfected into HeLa (epithelial), Jurkat (T lymphocyte), M12 (B lymphocyte), and BHK (fibroblast) cell lines. Their relative activities are compared in Table 1. Surprisingly, whereas the mut T mutation had no significant effect on promoter activity in HeLa epithelial cells, the same mutation markedly reduced class I promoter activity in Jurkat T cells while significantly increasing it in M12 B cells and BHK fibroblasts. The mut I mutation resulted in a significant reduction in promoter activity in HeLa epithelial and Jurkat T cells while increasing promoter function in BHK fibroblasts; its effect on M12 B cells was intermediate (Table 1). Additional mutations upstream of −30 bp had no effect on basal promoter function in HeLa cells (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Upstream regulatory sequences and cell-type-specific factors determine core promoter usagea

| Construct | Mean promoter construct activity (%) ± SE in cell line:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HeLa (epithelial) | Jurkat (T lymphocyte) | M12 (B lymphocyte) | BHK (fibroblasts) | |

| −416WT | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| −416mut T | 91.2 ± 3.6 | 64.6 ± 3.2 | 192.8 ± 5.6 | 141 ± 5.0 |

| −416mut I | 69.5 ± 2.2 | 72.0 ± 2.5 | 84.6 ± 5.4 | 149 ± 5.3 |

| −416mut S | 12.3 ± 0.4 | 9.2 ± 0.4 | 10.1 ± 0.6 | 27.6 ± 2.2 |

The effects of core promoter mutations were evaluated in different cell lines. Transfections with the promoter constructs were performed in parallel for each cell line; the data were normalized to −416WT and represent a compilation of at least 6 separate transfections. Data were corrected for transfection efficiency by using CMV-β-Gal. Since the transfection efficiencies of Jurkat and M12 cells are much lower than those of HeLa and BHK cells, a direct comparison of absolute class I promoter activity was not possible.

These data suggest that (i) the class I core promoter is not strictly dependent on the TATAA-like or Inr-like elements and (ii) these sequences function in a cell-type-specific fashion to modulate promoter activity. Further, since neither mutation eliminates promoter function, these data suggest that the class I promoter contains an alternative element(s) responsible for recruiting RNA Pol II for basal transcription.

Mutating the S-box greatly reduces MHC class I basal transcription.

We next characterized the effect of mutating the 18-bp region (S-box) located between bp −23 and −6 (Fig. 2A, mut S). In contrast to the mut T and mut I mutations, mut S dramatically reduced promoter activity both in vivo (Table 1) (24) and in vitro (Fig. 3A). In mut S, initiations at the upstream A-14 site were markedly reduced relative to those at the downstream +1 or +12 sites (Fig. 3A, compare lanes 2 and 3). Thus, a critical sequence(s) required for basal MHC class I expression resides within the S-box.

FIG. 3.

The S-box is essential for basal MHC class I transcription. (A) Mutation of the S-box in the extended −416 class I promoter construct (−416mut S, Fig. 2A) dramatically reduced transcription initiations in vitro. In vitro transcription reactions of −416WT and −416mut S constructs were analyzed by primer extension analysis. HeLa extract alone control is shown in the lane 1. Specific, transcriptional start sites generated by −416WT and −416mut S, in lanes 2 and 3, respectively, are indicated by the arrows. Additional, less-utilized start sites are observed throughout the WT core promoter region upon the longer exposure time required to observe initiations in −416mut S. (B) Scanning mutations of 4 bp across the S-box region were introduced into the −416 promoter construct to map the minimal S-box region required for basal transcription. Brackets indicate the 4-bp regions, M1 to M5, that were individually introduced into the −416 promoter construct. The mutated sequences appear at the bottom. (C) The effect of the S-box scanning mutants (M1 to M5) on in vitro transcription of the extended −416 promoter in HeLa extract was examined by primer extension analysis. Transcription start sites generated by the WT promoter are shown in lane 1, and those generated by mutants M1 to M5 are shown in lanes 2 to 6, respectively. The arrowheads indicate major transcriptional start sites, and the solid circle indicates a background band observed in HeLa extract control (not shown). Shadowed ellipses representing the upstream and downstream transcription regions where the major start sites were observed to originate (indicated by arrows) are provided for orientation.

The minimal sequence(s) within the S-box responsible for class I core promoter transcription was determined by generating a series of overlapping 4-bp mutations spanning the S-box region and assessing their activities in in vitro transcription reactions (Fig. 3B). Like the original Mut S, mutations spanning the central CA/GT-rich region of the S-box (M1 to M3) reduced in vitro transcription at all start sites (Fig. 3C, compare lanes 1 and 2 to 4). Mutant M4 had slightly reduced relative +1 and +12 start site usage (Fig. 3C, lane 5). The most 3′ mutation, M5, had no effect on start site usage (Fig. 3C, lane 6). These data indicate that the CA/GT-rich sequence between bp −21 and −12 is critical for class I basal promoter activity.

A specific complex binds the CA/GT-rich S-box sequence.

In order to identify transcription factors that interact with the S-box, the 64-bp core promoter region was used as a probe in gel shift analysis. Two principal complexes, indicated by the arrowheads, were generated with the WT class I core promoter probe and HeLa nuclear extract. (Fig. 4A, lane 2). Both complexes were competed for by increasing unlabeled WT competitor oligonucleotide (Fig. 4A, lanes 3 to 5). In contrast, a mut S oligonucleotide only competed the faster-migrating complex, indicated by the open arrowhead (Fig. 4A, lanes 6 to 8). When used directly as a probe in gel shift analysis, the mut S oligonucleotide failed to generate the slower-migrating S-box specific complex (data not shown). These data indicate that the slower-migrating complex, indicated by the solid arrowhead, specifically interacts with S-box sequences contained in the class I core promoter region.

In order to determine the precise binding site within the S-box, we utilized the panel of derivative oligonucleotides containing the overlapping 4-bp mutations across the S-box region, presented in Fig. 3B, as unlabeled competitors in gel shift analysis (Fig. 4B). Whereas an unlabeled WT oligonucleotide could compete complex binding to the WT core promoter probe, the scanning mutations M1, M2, and M3 were unable to do so (Fig. 4B, lanes 7 to 12). In contrast, mutations M4 and M5 were able to inhibit complex formation, although somewhat less efficiently than WT (Fig. 4B, lanes 13 to 16). Mutations outside the S-box (mut T) efficiently competed for the S-box specific complex (data not shown). This pattern of competition parallels the effect of these mutations on in vitro transcription (Fig. 3C). Taken together, these data indicate that a specific binding complex interacts with the central CA/GT-rich sequences, bp −21 to −12, of the S-box and suggest that it is necessary for transcription.

The transcription factor Sp1 binds the S-box.

CA/GT-rich sequences, similar to the class I core promoter element described above, have been reported to be Sp1-binding sites in other promoters (10, 13, 35). To determine whether Sp1 is a component of the S-box-specific complex, we added anti-Sp1 antisera to the gel shift reaction (Fig. 4C). Addition of anti-Sp1 antisera resulted in a supershift of the slower-migrating S-box complex (Fig. 4C, lane 4, solid circle). Control antisera had no effect (Fig. 4C, lane 3). Antisera to other Sp1 family members, including Sp2, Sp3, or Sp4, also had no effect on the S-box complex (Fig. 4C, lanes 5 to 7). Thus, the S-box-specific complex contains Sp1.

The faster-migrating complex was unaffected by the addition of anti-Sp1 antisera (Fig. 4C, open arrowhead). This complex was composed of single-stranded DNA binding factors since it could be effectively competed for by unlabeled sense or antisense single-stranded oligonucleotides (data not shown); the identity of these factors was not pursued. The slower-migrating complex, containing Sp1, was not competed for by increasing unlabeled single-stranded competitor oligonucleotides (data not shown).

Purified Sp1 protein (pSp1) generated a complex with the core promoter probe that migrated with the same mobility as the endogenous Sp1-containing complex derived from HeLa extract (Fig. 4D and data not shown). Similar to the Sp1-containing complex observed with HeLa extracts, pSp1 was supershifted by anti-Sp1 antisera (Fig. 4D, lane 3) and was competed for by WT but not by mut S oligonucleotides, respectively (Fig. 4D, lanes 4 and 5). These data demonstrate that Sp1 specifically interacts with the CA/GT-rich sequences in the class I core promoter.

The CA/GT-rich sequence is required for MHC class I expression in vivo.

The above data suggest a positive correlation between Sp1 binding and MHC class I promoter activity. Consistent with this correlation, we have demonstrated previously that Sp1 activates class I promoter activity in Schneider Drosophila cells, which lack endogenous Sp1 (24). Therefore, we determined whether the MHC core promoter mutant, −416Mut S, which does not bind Sp1 and does not support transcription in vitro, affects class I promoter activity in vivo. We examined basal class I promoter activity of −416Mut S in transiently transfected HeLa (epithelial), Jurkat T and M12 B (lymphocyte), and BHK (fibroblast) cell lines (Table 1). The four cell lines utilized in this analysis all expressed similar amounts of Sp1 protein and generated comparable Sp1-dependent complex formation with the WT core promoter probe in gel shift analyses (data not shown). Mutation of the Sp1-binding site led to a decrease of 75 to 90% in class I promoter activity in all cell lines (Table 1). These results suggest that Sp1, binding to the core promoter, recruits a transcriptional complex critical for MHC class I basal expression.

Basal transcription in vivo initiates in the upstream start site region.

The results described above demonstrate that basal class I transcription initiates at multiple sites and that it is directed by an Sp1-dependent mechanism. Although mutations that compromise Sp1 binding reduce all in vitro transcription initiations, they have a greater effect on upstream (A−18 and A−14) than downstream (A+1 and A+12) start site regions (Fig. 3C). This observation raises the question of whether the upstream and downstream start site regions are functionally distinct in vivo. To investigate this question, we introduced a mutation in the class I core promoter region that would distinguish upstream from downstream initiations, while preserving the overall structural and spatial integrity of the core promoter, as well as the Sp1-binding site. Two nucleotides in the core promoter region were mutated (underlined nucleotides in −416Mut−6, Fig. 5A), resulting in the creation of an ATG at the −6 position, in the context of a strong consensus Kozak sequence, interposed between upstream start sites (i.e., A−18 and A−14) and downstream start sites (i.e., A+1 and A+12) (Fig. 5A, −416Mut−6). Since this ATG is out of frame with respect to the downstream CAT reporter gene, any transcription starting upstream of −6 would not generate mRNA encoding CAT reporter enzyme in transient-transfection assays. On the other hand, transcripts initiating downstream of −6 in the −416Mut−6 construct should have no effect on subsequent translation of the CAT gene product. Thus, the −416Mut−6 distinguishes upstream from downstream transcription initiations.

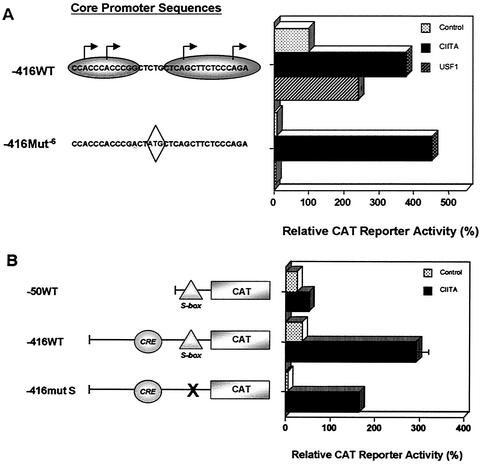

FIG. 5.

Basal MHC class I transcription initiates primarily in the upstream region of the core promoter. (A) HeLa cells were transiently transfected with MHC class I promoter constructs −416WT, −416Mut−6, and −416Con−6. Each construct, diagrammed on the left, was ligated to the CAT reporter. Specific mutations in the −416Mut−6 and −416Con−6 core promoter regions are underlined; the out-of-frame ATG generated in −416Mut−6 is enclosed in the diamond. There is no out-of-frame ATG in −416Con−6. The upstream and downstream start site regions observed in in vitro transcription (indicated by the shadowed ellipses) are provided for orientation. Data are expressed as relative percentages of acetylation corrected to the transfection control, pSV2LUC. Error bars indicate the standard error. (B) −416WT and −416Mut−6 promoter regions were ligated upstream of CAT or luciferase reporters. The specific mutations in Mut−6 are underlined. The ATG introduced by the Mut−6 mutations is out of frame with respect to the CAT reporter but in frame with the luciferase reporter. Data are expressed as relative percentages of reporter activities (CAT or luciferase) corrected to the transfection control, pSV2LUC or CMV-β-Gal, respectively. Error bars indicate the standard error. (C) −416WT and −416Mut−6 core promoter sequences, ligated to the CAT reporter, were transcribed in vitro to determine start site usage. Lane 1 is the WT promoter; the major start sites are indicated by arrows. Lane 2 represents the start sites generated by −416Mut−6 in in vitro transcription. The upstream and downstream start site regions indicated by the shadowed ellipses are provided for orientation (the major start sites are indicated by arrows). The solid circle marks a nonspecific band.

Transient transfection of 416Mut−6 into HeLa epithelial cells resulted in greatly reduced levels of CAT reporter enzyme activity relative to the −416WT construct, indicating that basal transcription initiates primarily from the upstream start site region (Fig. 5A). This result is consistent with the observation that the −14 start site is the preferred start site in basal in vitro transcription in HeLa extracts (Fig. 1B). As a control, the A-6 and T-5 residues were reversed (−416Con−6), thereby eliminating the out-of-frame ATG, and activity was fully restored (Fig. 5A). This control also demonstrates that the nucleotide changes at these positions do not affect in vivo promoter function. As an additional control, the class I core promoter, containing the ATG−6 mutation, was subcloned in frame with the luciferase reporter. Consistent with the interpretation that basal promoter activity initiates predominantly upstream of −6, the ATG−6 mutation, which is out of frame for CAT and does not generate CAT enzyme activity, does generate luciferase activity when present in-frame with the luciferase gene (Fig. 5B). The ATG−6 mutant does not affect class I core promoter activity nonspecifically, since −416Mut−6 was as active as the WT class I promoter (−416WT) in in vitro transcription (Fig. 5C). Although some downstream initiation is observed in vitro with HeLa nuclear extract, the A−14 upstream site is still the dominant start site in vitro. Taken together, these data demonstrate that the majority of basal class I transcription in vivo initiates from the upstream region.

Basal and activated class I transcriptions are mediated by separable molecular pathways.

Since basal expression initiates primarily through the upstream start site region, we next examined which initiation sites are targeted in activated class I transcription. The MHC class I promoter is known to be activated by several transcription factors, including CIITA (20, 38, 43, 63) and USF1 (23). Whereas USF1 is constitutively expressed in all cell types and contributes to basal, tissue-specific expression, CIITA is expressed constitutively only in B lymphocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. CIITA is induced in many cell types by IFN-γ, in response to viral infection, and regulates dynamically activated class I expression. Therefore, we next compared the effects of CIITA and USF1 on MHC class I transcription in vivo and in vitro. As we have shown previously (20, 23, 38, 43, 63) in transient transfections, the WT (−416WT) promoter is active in basal transcription and is further activated by both USF1 and CIITA by 2.5- and 4-fold, respectively (Fig. 6A). The −416Mut−6 promoter construct, which does not generate CAT enzyme basally, is not induced to do so in the presence of USF1. Thus, USF1 activates through the upstream start sites. In surprising and marked contrast, CIITA dramatically activated the −416Mut−6 promoter, as assessed by production of CAT enzyme (Fig. 6A). These data suggest that CIITA redirects transcription initiation from the upstream start sites to the downstream start site region.

FIG. 6.

The IFN-γ-induced coactivator CIITA, but not USF1, redirects class I transcription through the downstream start site region and does not require an intact S-box. (A) −416WT and −416Mut−6 promoter constructs ligated to the CAT reporter (5 μg) diagrammed on the left were transiently cotransfected into HeLa epithelial cells with either CIITA (2 μg) or USF1 (2 μg) expression constructs. The upstream and downstream start site regions (indicated by the shadowed ellipses) are provided for orientation; the major start sites observed in in vitro transcription are indicated by arrows, and the class I core promoter sequences they span are indicated. Specific mutations in −416Mut−6 are underlined; the out-of-frame ATG is enclosed in the diamond. Data are expressed as relative percentages of acetylation corrected to the transfection control, pSV2LUC. Error bars indicate the standard errors. (B) CIITA-activated class I promoter activity does not require an intact S-box. −50 WT, −416WT, and −416mut S-box constructs (5 μg), diagrammed on the left, were transiently transfected into HeLa epithelial cells with a CIITA expression construct or control vector (2 μg). The upstream CRE element, required for CIITA activation, is indicated. The S-box is represented by the shaded triangle. Data are expressed as relative percentages of acetylation corrected to the transfection control, pSV2LUC. The error bars indicate the standard errors.

These results also raise the possibility that the composition of basal and activated transcriptional complexes in MHC class I expression may be distinct. As demonstrated above (Fig. 3 and 4 and Table 1), basal transcription from the class I promoter is dependent upon Sp1. The finding that CIITA preferentially targets initiation to downstream start sites raises the question of whether Sp1 also is necessary in CIITA-activated transcription. To examine this possibility, we determined whether CIITA-activated transcription, like basal transcription, was dependent on Sp1 binding to the S-box in vivo. The ability of CIITA to activate −416mut S, which contains an S-box core promoter mutation that is unable to bind Sp1, was assessed (Fig. 6B). As expected, the −416mut S was inactive in the absence of CIITA. However, remarkably, in the presence of CIITA, the −416mut S promoter was highly active. Indeed, its activity in the presence of CIITA was nearly twice that of the WT control, approaching that of the CIITA-activated −416WT control. [The difference in measured CAT activities between CIITA-activated −416WT and −416mutS is attributable to the contribution of basal activity to the net CAT activity of the CIITA-activated −416WT.] The core promoter construct −50WT, which does not have the CIITA-target CRE element, was not significantly activated by CIITA (Fig. 6B). These studies extend our earlier findings (43) and demonstrate that CIITA activation of the class I promoter, unlike basal transcription, does not require Sp1 binding.

Activated transcription in vivo in transgenic mice is predominantly in the downstream region.

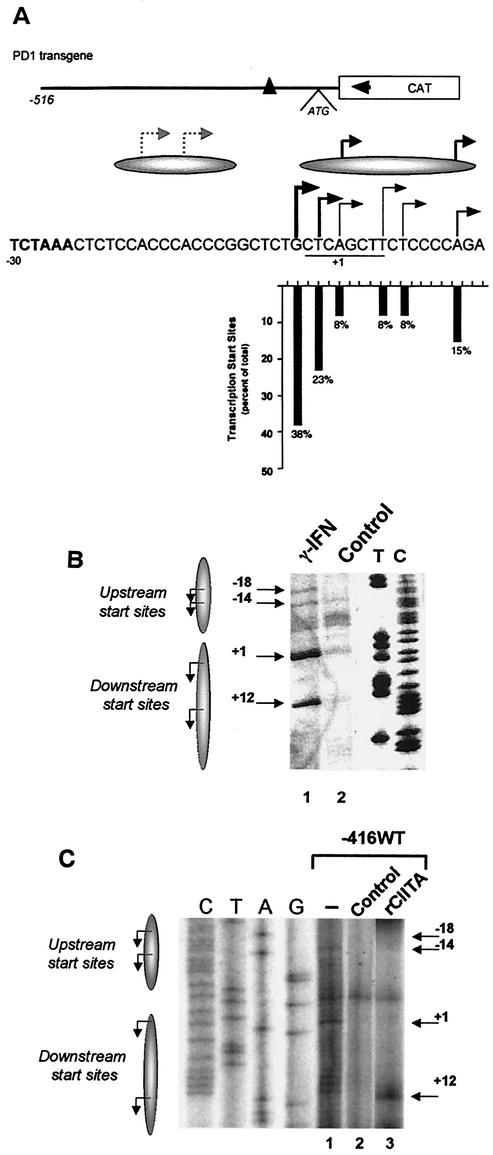

The results presented above suggest that CIITA redirects class I transcription initiation downstream. To determine whether activated transcription initiates at downstream sites in vivo, start sites were assessed in splenocytes which contain a large B-cell compartment, as well as dendritic cells and macrophages, all of which constitutively express CIITA. In these cells, class I transcription is constitutively activated and would be predicted to initiate predominantly at the downstream start site region. The MHC contains multiple class I genes, all of which are highly homologous, in both their coding and upstream sequences, making it difficult to unambiguously define the start site of any one endogenous gene. To circumvent this problem, we examined transcription of a hybrid transgene containing 516 bp of the PD1 class I promoter sequence (positions −516 to +45, including the ATG of the first exon) upstream of the CAT reporter gene (Fig. 7A). In previous studies, we demonstrated that the in vivo pattern of expression of this hybrid transgene parallels that of the endogenous murine H-2 class I genes (37). To identify transcript initiation sites, we performed 5′RACE analysis with a CAT-specific primer that distinguished PD1 promoter transgene transcripts from endogenous MHC class I promoter directed transcripts. The 5′RACE products were generated from splenic RNA and cloned. Critical to this analysis, subsequent sequencing of appropriate clones allowed unambiguous identification of transcription initiation start site(s) generated by the class I transgene. As shown in Fig. 7A, multiple specific start sites were detected, all of which were located in the downstream start site region of the class I core promoter. (It should be noted that the −2 and −4 start sites that predominate in vivo would not have been detected in vitro, due to a strong nonspecific band present in the HeLa nuclear extract [see Fig. 1B]; the +5 and +7 start sites were observed occasionally.) These data demonstrate that in a population of cells where class I expression is activated, most transcription initiates at the downstream sites.

FIG. 7.

Mapping basal and activated MHC class I initiation sites in vivo. (A) Results of 5′RACE analysis of −516CAT transgenic spleen RNA to map class I start sites utilized by splenocytes in vivo. The transgene, shown at the top of the figure, extends from −516 to +45 (−516CAT) and is ligated to the CAT reporter gene. The translation initiation codon of the PD1 class I gene is shown relative to the CAT reporter gene; the location of the CAT gene-specific primer used in 5′RACE is indicated by the left arrowhead. 5′RACE products derived from −516CAT transgenic spleen RNA were generated and cloned. More than 300 clones were screened by hybridization; 16 contained class I sequences. All 16 were sequenced to determine the precise transcription initiation sites. Initiation sites, and their relative usage are indicated by the position and size of the right-hand arrows. The relative frequency with which individual sites are used is also indicated at the bottom of the figure and is aligned to the sequence above. Shaded ellipses representing the upstream and downstream transcription regions where the major start sites originate (indicated by arrows) is provided for orientation. The gray, broken arrows represent the upstream start sites that contribute to basal expression, in vitro and in vivo, as determined by primer extension. (B) Nuclear extracts from control and IFN-γ-treated HeLa cells were used in in vitro transcription reactions with a class I reporter construct −516CAT (−516 to +45). Primer extension of in vitro-transcribed RNA was used to identify specific start sites. In vitro generated transcripts generated by IFN-γ-treated HeLa nuclear extract are shown in lane 1; control HeLa extract is shown in lane 2. (C) Purified rCIITA or control lysate from baculovirus-infected cells were added to in vitro transcription reactions by using the class I promoter construct −416WT; specific start sites were detected by using primer extension analysis. Class I-specific transcript in the presence of HeLa extract without added baculovirus lysate is shown in the lane 1. Additions of control lysate and purified rCIITA are shown in lanes 2 and 3, respectively. The principal transcription start sites, detected in Fig. 1B, are indicated by the arrows. Shaded ellipses representing the upstream and downstream transcription regions where the major start sites originate (indicated by arrows) are provided on the left for orientation. A sequence ladder of the class I promoter is also included.

We next determined whether IFN-γ could actively alter MHC class I promoter initiation start site usage. Nuclear extracts from either control or IFN-γ-treated HeLa cells were used to direct in vitro transcription of the bp −516 to +45 promoter segment (the same one present in the transgene) (Fig. 7B). The overall pattern of start site selection paralleled that observed in vivo and did not differ between the two nuclear extracts. However, consistent with the in vivo pattern, the relative usage of the downstream start sites was markedly increased by IFN-γ treatment (Fig. 7B, lane 1), compared to the control: initiation from both the A+1 and A+12 start sites was dramatically increased, while other start sites, including the A−14 and A−18 start sites, were either unchanged or increased only slightly.

IFN-γ is known to induce the expression, or activation, of other transcription factors in addition to CIITA. Therefore, we next determined whether CIITA alone was capable of altering class I promoter transcription initiation. rCIITA, purified from baculovirus-infected cells, was added to untreated HeLa nuclear extract, and its effect on in vitro transcription from the class I promoter was determined (Fig. 7C). Indeed, rCIITA markedly enhanced downstream start site transcript initiation, notably at position +12 (Fig. 7C, lane 3). [Note that the control baculovirus lysate nonspecifically repressed basal transcription (Fig. 7C, lane 2).] These data demonstrate that in the presence of rCIITA, class I transcription preferentially initiates in the downstream start site region. These results are consistent with the ability of CIITA to overcome the out-of-frame ATG in the −416Mut−6 (Fig. 6A), resulting in the generation of CAT enzyme activity in transiently transfected HeLa cells.

Taken together with the finding that basal transcription initiates primarily at upstream sites (Fig. 1C), these findings demonstrate that transcription in vivo initiates at multiple sites, whose usage differs according to the operative regulatory pathway. Basal class I transcripts are Sp1 dependent and skewed to initiate at the upstream start site region. A distinct activated transcriptional pathway, regulated at least in part by CIITA and independent of Sp1, skews initiation to the downstream start site region.

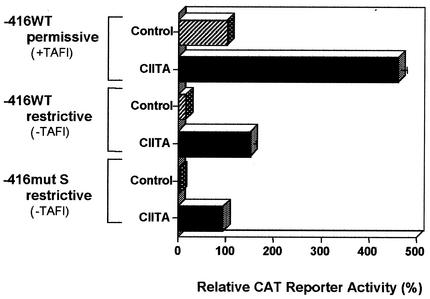

Basal and activated MHC class I transcriptions differ in their GTF requirements.

In previous studies we demonstrated that basal class I transcription is TAF1 (TAFII250) dependent: transcription is abrogated at the restrictive temperature in the tsBN462 hamster cell line, which carries a temperature-sensitive mutation in TAF1 (TAFII250) (48). The present finding that distinct transcription pathways target distinct class I initiation sites suggested that basal and CIITA-activated transcription may also have distinct GTF requirements. Indeed, CIITA activates class I expression in the tsBN462 cells at both the permissive and the restrictive temperatures, indicating that CIITA-activated class I expression is TAF1 (TAFII250) independent (Fig. 8 and reference 43).

FIG. 8.

The IFN-γ-induced coactivator CIITA activates a TAF1 (TAFII250)-independent, Sp1-independent transcription pathway that targets downstream initiation sites. −416WT (5 μg) and −416mut S (5 μg) were transfected at 32°C into the tsBN462 cell line (containing a temperature-sensitive mutant TAF1 [TAFII250] molecule) in the presence or absence of a CIITA expression construct. After 24 h, cells were shifted to 39°C or maintained at 32°C and then incubated for an additional 24 h. The promoters of theCMV-CIITA expression vector and the simian virus 40 pSV2LUC internal are not affected by the temperature shift. The results are presented as promoter activity as assayed by CAT enzyme relative to the −416WT control levels at 32°C. The error bars represent the standard error.

Thus, CIITA-activated transcription, unlike basal transcription, is TAF1 (TAFII250) independent, Sp1 independent, and targets transcription initiation to downstream start sites. The extent to which activated and basal transcription differ in their overall requirements was assessed by examining the ability of the CIITA-activated pathway to stimulate transcription of the −416mut S mutant in the tsBN462 cells at the restrictive temperature. As shown above, the −416mut S mutant is unable to bind Sp1 and only monitors downstream transcription initiation. Examining its ability to direct CAT enzyme synthesis in the tsBN462 cells allows us to simultaneously assess the requirements for Sp1 and TAF1 (TAFII250) and transcription initiation sites. Indeed, in the presence of CIITA, −416mut S directs the synthesis of CAT enzyme at the restrictive temperature (Fig. 8). In the absence of CIITA, the construct fails to direct any detectable CAT synthesis at either temperature (Fig. 8 and data not shown). Therefore, CIITA-activated transcription, unlike basal transcription, requires neither Sp1 nor TAF1 (TAFII250), and targets downstream initiation sites.

Activated transcription is not repressed by HIV-1 Tat.

In earlier studies, we reported that the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) transactivator, Tat, represses basal class I transcription by binding TAF1 (TAFII250) and inhibiting its acetyltransferase activity (26, 62). If CIITA activates class I transcription through a distinct, TAF1 (TAFII250)-independent pathway, then HIV-1 Tat should not inhibit CIITA-activated transcription. We tested this prediction by examining the effect of HIV-1 Tat on CIITA-activated −416mut S promoter activity (Table 2). Consistent with the prediction, Tat did not repress the CIITA-activated, TAF1 (TAFII250)-independent class I expression of −416mut S but did repress the TAF1 (TAFII250)-dependent, basal class I promoter activity of −416WT (Table 2). These results demonstrate that basal and activated transcription represent distinct regulatory pathways that utilize distinct promoter elements, depend on distinct transcription factors, and assemble distinct preinitiation complexes.

TABLE 2.

CIITA activated, TAF1-independent MHC class I expression is not repressed by HIV Tata

| Construct | Pathway | Mean activity (%) ± SE

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Tat | ||

| −416WT | TAFI dependent | 100 | 28.0 ± 0.5 |

| −416mut S + control | TAFI dependent | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.1 |

| −416mut S + CIITA | TAFI independent | 100 | 100.8 ± 4.0 |

The ability of HIV-1 Tat to repress CIITA-activated WT or mutant S −416 reporter constructs was examined in transiently transfected HeLa cells. Data were corrected for the pSV2LUC internal transfection control. The activity of −416WT and −416mut S + CIITA are set at 100%; the activity of −416mut S + control is relative to that of −416WT.

DISCUSSION

The present studies demonstrate that activated and basal transcription target distinct sites within the class I core promoter and have distinct activator and GTF requirements. Basal transcription initiates primarily at upstream sites within the core promoter, requires the presence of an intact Sp1-binding element and is TAF1 (TAFII250) dependent. In marked contrast, activated transcription, as defined by the IFN-γ-induced coactivator CIITA, initiates transcription primarily at downstream sites, is unaffected by mutations that disable Sp1 binding, and is TAF1 (TAFII250) independent. These studies demonstrate that basal and activated modes of MHC class I transcription are regulated by distinct pathways that converge on a single core promoter.

Consistent with a role in integrating multiple transcriptional pathways, the MHC class I core promoter is complex, both in its organization and function. The core promoter is encompassed within a 65-bp DNA fragment (bp −50 to +14): this segment is sufficient to mediate basal transcription and is necessary for activated transcription. Transcription initiation occurs at multiple but largely nonoverlapping sites in both basal and activated transcription. Although sequences homologous to canonical TATA (bp −30 to −25) and Inr elements (bp −3 to +5) occur in this segment and contribute to overall promoter activity, neither of these is necessary for either transcriptional pathway. Two Inr-like sequences also occur within the central S-box, overlapping both sites of initiation of basal transcription and Sp1-binding sites. These sequences may function as Inr elements in basal transcription but are not necessary for activated transcription. Thus, no single element within the core promoter is necessary for all transcription.

The promoter of the MHC class I gene, PD1, occurs within a CpG island (40). The interval between bp −300 and +300 contains 41 CpG and 53 GpC motifs. Such CpG islands are generally undermethylated and contain promoters for a variety of genes, commonly housekeeping genes. The GpC motifs often serve as binding sites for Sp1, which may serve both to recruit general transcription factors and to maintain the hypomethylated state. Promoters within CpG islands often do not have canonical TATA or Inr sequences and initiate at multiple sites. Consistent with the suggestion that the class I promoter is a CpG island promoter is the lack of canonical promoter elements. The TATA-like and Inr-like elements are not necessary for transcription, and no TBP binding has been observed to the TATA-like element (K. Howcroft and D. Singer, unpublished observations). No sequences with homology to either DPE or DCE elements are found within the core promoter. A classical TFIIB-binding site, BRE, occurs at bp −51 to −46, but there is no evidence that it functions as a regulatory element; neither TFIIB nor the TATA-binding protein have been observed to bind the BRE, either alone or in combination (Z. Sercan and D. S. Singer, unpublished data). Further, factors that have been reported to bind to the Inr, such as TFII I, USF (46, 47), and YY1 (34, 58) do not bind to the core promoter (T. K. Howcroft, J. D. Weissman, and D. S. Singer, unpublished results). Thus, the class I core promoter structurally resembles other CpG island promoters.

Through its complex structure, the class I core promoter dynamically integrates disparate regulatory signals. As demonstrated in the present study, the multiplicity of transcription start sites within the class I core promoter reflects differential start site usage for activated and basal transcription. Basal transcription is focused on initiation sites upstream of bp −6, primarily at bp −14 and −18, within the S-box. In contrast, activated transcription initiates downstream of −6 bp, primarily between bp −4 and +12. This differential usage correlates with promoter element specificity, activator factor requirements, and general transcription factor dependence. Thus, basal transcription depends on the S-box element, on the Sp1 activator binding to the S-box and on the general transcription factor, TAF1. Activated transcription requires none of these. Such core promoter element specificity, linked with differential transcription factor usage, has been termed “combinatorial regulation” and has been reported in a number of systems (55). In Drosophila, it has been demonstrated that enhancers are specific either for promoters with TATA or with DPE elements (8). Similarly, in the mouse TdT gene, promoter activity depends on the interaction between enhancer elements and the native Inr, which cannot be replaced by a TATA element. However, artificial introduction of both Sp1 and TATA elements into the TdT promoter restores activity (12). Thus, there is regulation through appropriate enhancer/promoter element combinations. However, in these examples, regulation is static: a single promoter uses one enhancer-promoter element combination.

In marked contrast, the class I promoter has at least two distinct enhancer-promoter element combinations and displays dynamic combinatorial regulation under different physiological conditions. Basal and activated transcription invoke nonoverlapping combinations within the same core promoter. Only the yeast HIS3 promoter is known to have a similar dynamic combinatorial regulation. This promoter has two TATAA elements: a downstream canonical one and an upstream variant. At low levels of transcription, the variant element is used preferentially, whereas at high levels of transcription, the canonical TATA is used (28). In contrast to the class I promoter, the differential usage of HIS3 TATA elements does not reflect differential activator protein function.

Differential start site usage in the class I core promoter depends on both activator and general transcription factor function. Basal transcription is regulated by tissue-specific but constitutively expressed activators, such as Sp1 and USF. Class I basal transcription in all cell types depends on Sp1 binding to the S-box, and in particular to the central 10-bp CA/GT-rich sequence, where basal transcription initiates. We speculate that Sp1 focuses basal transcription to this upstream region by recruiting the transcription machinery, maintaining an undermethylated state around the promoter, or both. Sp1 is known to recruit RNA Pol II through its interaction with the TAF4 (TAFII110) subunit of TFIID (61). The constitutively expressed USF also activates through the basal pathway. In addition to the upstream E-box element, USF-enhanced transcription requires an intact S-box (data not shown), requires TAF1 (63), and targets the upstream start sites. We suggest that the class I S-box, through recruitment of the appropriate preinitiation complex (PIC), integrates the constitutive tissue-specific signals of the basal transcription pathway.

Although the S-box is the major core promoter sequence required for basal transcription, it is not involved in activated transcription. CIITA-activated transcription is unaffected by mutation of the S-box. Based on our findings, we propose that hormone- or cytokine-regulated activators, such as CIITA, function through an alternative transcription pathway with promoter element requirements distinct from those of basal transcription. We further suggest that activated transcription pathways recruit novel PIC(s) that have components distinct from those assembled under basal conditions, which in turn, differentially target the various core promoter elements.

What is the significance of having distinct transcriptional pathways to express MHC class I genes? We speculate that the CIITA-activated transcription pathway is an adaptive strategy for continued MHC class I expression under pathologically adverse conditions. For example, many viruses can actively repress MHC class I basal transcription in order to prevent detection and destruction by MHC class I-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes (4, 22, 39). Previous studies from our lab have demonstrated that HIV-1 Tat specifically interacts with the TAF1 (TAFII250) subunit of TFIID and inhibits its acetyltransferase activity (62). Since MHC class I expression is TAF1 (TAFII250) dependent, this process results in repression of basal transcription and reduced cell surface expression of MHC class I (24, 26). In the present study we demonstrate that CIITA, which has intrinsic acetyltransferase activity (43), activates an alternate TAF1 (TAFII250)-independent pathway of MHC class I expression that is resistant to Tat repression. Thus, the TAF1 (TAFII250)-independent pathway activated by CIITA bypasses the Tat repressed basal pathway and promotes class I expression in HIV-1-infected cells.

In conclusion, the present studies have defined two distinct transcriptional pathways that regulate MHC class I gene expression. We propose that proper class I expression is achieved by the appropriate integration of these two pathways. We speculate that this system has the further selective advantage of ensuring continued immune surveillance in the face of intracellular pathogens.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Joshua Meyers and Stacey McLaughlin for their technical assistance and John Brady, David Levens, and Danny Reinberg for helpful discussion and critical review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aso, T., J. W. Conaway, and R. C. Conaway. 1994. Role of core promoter structure in assembly of the RNA polymerase II ormattedpreinitiation complex: a common pathway for formation of preinitiation intermediates at many TATA and TATA-less promoters. J. Biol. Chem. 269:26575-26583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldwin, A. S., Jr., and P. A. Sharp. 1987. Binding of a nuclear factor to a regulatory sequence in the promoter of the mouse H-2Kb class I major histocompatibility gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7:305-313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berk, A. J. 1999. Activation of RNA polymerase II transcription. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 11:330-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brodsky, F. M. 1999. Stealth, sabotage, and exploitation. Immunol. Rev. 168:5-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burke, T. W., and J. T. Kadonaga. 1997. The downstream core promoter element, DPE, is conserved from Drosophila to humans and is recognized by TAFII60 of Drosophila. Genes Dev. 11:3020-3031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burke, T. W., and J. T. Kadonaga. 1996. Drosophila TFIID binds to a conserved downstream basal promoter element that is present in many TATA-box-deficient promoters. Genes Dev. 10:711-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burley, S. K. 1996. The TATA box binding protein. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 6:69-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butler, J. E., and J. T. Kadonaga. 2001. Enhancer-promoter specificity mediated by DPE or TATA core promoter motifs. Genes Dev. 15:2515-2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butler, J. E., and J. T. Kadonaga. 2002. The RNA polymerase II core promoter: a key component in the regulation of gene expression. Genes Dev. 16:2583-2592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen, L. I., T. Nishinaka, K. Kwan, I. Kitabayashi, K. Yokoyama, Y. H. Fu, S. Grunwald, and R. Chiu. 1994. The retinoblastoma gene product RB stimulates Sp1-mediated transcription by liberating Sp1 from a negative regulator. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:4380-4389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.David-Watine, B., A. Israel, and P. Kourilsky. 1990. The regulation and expression of MHC class I genes. Immunol. Today 11:286-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emami, K. H., W. W. Navarre, and S. T. Smale. 1995. Core promoter specificities of the Sp1 and VP16 transcriptional activation domains. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:5906-5916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischer, K. D., A. Haese, and J. Nowock. 1993. Cooperation of GATA-1 and Sp1 can result in synergistic transcriptional activation or interference. J. Biol. Chem. 268:23915-23923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frels, W. I., J. A. Bluestone, R. J. Hodes, M. R. Capecchi, and D. S. Singer. 1985. Expression of a microinjected porcine class I major histocompatibility complex gene in transgenic mice. Science 228:577-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gardiner-Garden, M., and M. Frommer. 1987. CpG islands in vertebrate genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 196:261-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gill, G. 2001. Regulation of the initiation of eukaryotic transcription. Essays Biochem. 37:33-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Girdlestone, J. 1995. Regulation of HLA class I loci by interferons. Immunobiology 193:229-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Girdlestone, J. 1996. Transcriptional regulation of MHC class I genes. Eur. J. Immunogenet. 23:395-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gobin, S. J., V. Keijsers, M. van Zutphen, and P. J. van den Elsen. 1998. The role of enhancer A in the locus-specific transactivation of classical and nonclassical HLA class I genes by nuclear factor κB. J. Immunol. 161:2276-2283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gobin, S. J., A. Peijnenburg, V. Keijsers, and P. J. van den Elsen. 1997. Site alpha is crucial for two routes of IFN gamma-induced MHC class I transactivation: the ISRE-mediated route and a novel pathway involving CIITA. Immunity 6:601-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hampsey, M. 1998. Molecular genetics of the RNA polymerase II general transcriptional machinery. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:465-503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Howcroft, T. K. 2000. HIV-1: a molecular toolkit for analysis of major histocompatibility complex class I expression. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 30:657-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howcroft, T. K., C. Murphy, J. D. Weissman, S. J. Huber, M. Sawadogo, and D. S. Singer. 1999. Upstream stimulatory factor regulates major histocompatibility complex class I gene expression: the U2ΔE4 splice variant abrogates E-box activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:4788-4797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howcroft, T. K., L. A. Palmer, J. Brown, B. Rellahan, F. Kashanchi, J. N. Brady, and D. S. Singer. 1995. HIV Tat represses transcription through Sp1-like elements in the basal promoter. Immunity 3:127-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howcroft, T. K., J. C. Richardson, and D. S. Singer. 1993. MHC class I gene expression is negatively regulated by the proto-oncogene, c-jun. EMBO J. 12:3163-3169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Howcroft, T. K., K. Strebel, M. A. Martin, and D. S. Singer. 1993. Repression of MHC class I gene promoter activity by two-exon Tat of HIV. Science 260:1320-1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ishiguro, N., G. D. Brown, and D. Meruelo. 1997. Activation transcription factor 1 involvement in the regulation of murine H-2Dd expression. J. Biol. Chem. 272:15993-16001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iyer, V., and K. Struhl. 1995. Mechanism of differential utilization of the his3 TR and TC TATA elements. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:7059-7066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaufmann, J., K. Ahrens, R. Koop, S. T. Smale, and R. Muller. 1998. CIF150, a human cofactor for transcription factor IID-dependent initiator function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:233-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaufmann, J., and S. T. Smale. 1994. Direct recognition of initiator elements by a component of the transcription factor IID complex. Genes Dev. 8:821-829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kutach, A. K., and J. T. Kadonaga. 2000. The downstream promoter element DPE appears to be as widely used as the TATA box in Drosophila core promoters. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:4754-4764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lagrange, T., A. N. Kapanidis, H. Tang, D. Reinberg, and R. H. Ebright. 1998. New core promoter element in RNA polymerase II-dependent transcription: sequence-specific DNA binding by transcription factor IIB. Genes Dev. 12:34-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Le Bouteiller, P. 1994. HLA class I chromosomal region, genes, and products: facts and questions. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 14:89-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee, J. S., K. M. Galvin, and Y. Shi. 1993. Evidence for physical interaction between the zinc-finger transcription factors YY1 and Sp1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:6145-6149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liang, Y., D. F. Robinson, G. C. Kujoth, and W. E. Fahl. 1996. Functional analysis of the SIS proximal element and its activating factors: regulated transcription of the c-SIS/PDGF-B gene in human erythroleukemia cells. Oncogene 13:863-871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lo, K., and S. T. Smale. 1996. Generality of a functional initiator consensus sequence. Gene 182:13-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maguire, J. E., W. I. Frels, J. C. Richardson, J. D. Weissman, and D. S. Singer. 1992. In vivo function of regulatory DNA sequence elements of a major histocompatibility complex class I gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:3078-3086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin, B. K., K. C. Chin, J. C. Olsen, C. A. Skinner, A. Dey, K. Ozato, and J. P. Ting. 1997. Induction of MHC class I expression by the MHC class II transactivator CIITA. Immunity 6:591-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maudsley, D. J., and J. D. Pound. 1991. Modulation of MHC antigen expression by viruses and oncogenes. Immunol. Today 12:429-431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McQueen, H. A., V. H. Clark, A. P. Bird, M. Yerle, and A. L. Archibald. 1997. CpG islands of the pig. Genome Res. 7:924-931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murphy, C., D. Nikodem, K. Howcroft, J. D. Weissman, and D. S. Singer. 1996. Active repression of major histocompatibility complex class I genes in a human neuroblastoma cell line. J. Biol. Chem. 271:30992-30999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nagarajan, U. M., A. Peijnenburg, S. J. Gobin, J. M. Boss, and P. J. van den elsen. 2000. Novel mutations within the RFX-B gene and partial rescue of, M. H. C., and related genes through exogenous class II transactivator in RFX-B-deficient cells. J. Immunol. 164:3666-3674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raval, A., T. K. Howcroft, J. D. Weissman, S. Kirshner, X. S. Zhu, K. Yokoyama, J. Ting, and D. S. Singer. 2001. Transcriptional coactivator, CIITA, is an acetyltransferase that bypasses a promoter requirement for TAFII250. Mol. Cell 7:105-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reinberg, D., G. Orphanides, R. Ebright, S. Akoulitchev, J. Carcamo, H. Cho, P. Cortes, R. Drapkin, O. Flores, I. Ha, J. A. Inostroza, S. Kim, T. K. Kim, P. Kumar, T. Lagrange, G. LeRoy, H. Lu, D. M. Ma, E. Maldonado, A. Merino, F. Mermelstein, I. Olave, M. Sheldon, R. Shiekhattar, L. Zawel, et al. 1998. The RNA polymerase II general transcription factors: past, present, and future. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 63:83-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roeder, R. G. 1996. The role of general initiation factors in transcription by RNA polymerase II. Trends Biochem. Sci. 21:327-335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roy, A. L., S. Malik, M. Meisterernst, and R. G. Roeder. 1993. An alternative pathway for transcription initiation involving TFII-I. Nature 365:355-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roy, A. L., M. Meisterernst, P. Pognonec, and R. G. Roeder. 1991. Cooperative interaction of an initiator-binding transcription initiation factor and the helix-loop-helix activator USF. Nature 354:245-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sekiguchi, T., Y. Nohiro, Y. Nakamura, N. Hisamoto, and T. Nishimoto. 1991. The human CCG1 gene, essential for progression of the G1 phase, encodes a 210-kilodalton nuclear DNA-binding protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:3317-3325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singer, D. S., R. D. Camerini-Otero, M. L. Satz, B. Osborne, D. Sachs, and S. Rudikoff. 1982. Characterization of a porcine genomic clone encoding a major histocompatibility antigen: expression in mouse L cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 79:1403-1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Singer, D. S., and R. Ehrlich. 1988. Identification of regulatory elements associated with a class I MHC gene. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 137:148-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Singer, D. S., and J. E. Maguire. 1990. Regulation of the expression of class I MHC genes. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 10:235-257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Singer, D. S., E. Mozes, S. Kirshner, and L. D. Kohn. 1997. Role of MHC class I molecules in autoimmune disease. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 17:463-468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Singer, V. L., C. R. Wobbe, and K. Struhl. 1990. A wide variety of DNA sequences can functionally replace a yeast TATA element for transcriptional activation. Genes Dev. 4:636-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]