Abstract

We previously showed that intracerebral (ic) inoculation of the attenuated SY strain of Creutzfeld–Jakob disease in mice could delay clinical signs and widespread neuropathology evoked by subsequent ic challenge with the more virulent FU strain. Using lower doses of SY and FU ic, we here demonstrate that mice can be protected well into old age without demonstrable neuropathology or pathologic prion protein (PrP-res). In contrast, parallel FU only controls became terminally diseased 1 year earlier. To determine whether factors elaborated in response to SY might be part of this effect, we evaluated brain and serum samples from additional parallel mice at 90 days after SY infection and just before FU challenge. The infectivity of FU preparations was significantly reduced by mixing with these fresh SY brain homogenates but not by mixing with SY serum samples, suggesting that brain cells were elaborating labile inhibitory factors that were part of the protective response. SY infectivity was too low to be detected in these brain homogenates. Although suppression could be overcome by higher FU doses ic, strong protection against maximal doses of FU was observed by using i.v. inoculations. Because myeloid microglia are infectious and also elaborate many factors in response to the foreign Creutzfeld–Jakob disease agent, it is likely that innate immunity underlies the profound protection shown here. In principle, it should be possible to artificially stimulate relevant myeloid pathways to better prevent and/or delay the clinical and pathological sequelae of these infections.

Keywords: agent strains‖prion protein‖brain factors‖antibodies‖myeloid cells

Many viruses, including those that evade classical immune responses, can evoke an interference response whereby infection with one viral strain can inhibit later superinfection by a second viral strain. In previous experiments, we showed that the slow SY agent, propagated from a typical “sporadic” case of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD), could prevent superinfection by the more virulent and faster replicating FU agent from Japan (1). The suppression of FU was obvious, even with direct intracerebral (ic) injection of reasonably high doses of FU brain homogenates. Mice first inoculated with uninfected brain and later challenged with FU showed the same short incubation period as mice given only FU. In contrast, there was a dramatic ≈150-day delay in of CJD signs in mice first inoculated with SY. These SY-protected mice also exhibited a distinctive SY scratching syndrome, also seen in parallel SY only controls, but not in FU-infected mice. Furthermore, in 16 of 18 SY-protected mice, only the SY neuropathologic profile of minimal and highly localized lesions was seen without the widespread lesions evoked by the FU agent. Thus, it was apparent that the relatively avirulent SY agent itself, or a host response to this exogenous infectious agent, was capable of inhibiting and/or clearing the more virulent FU agent.

Interestingly, levels of abnormally folded prion protein (PrP-res) were barely detectable in SY-protected mice assayed at very late stages of incubation, just before clinical signs appeared. PrP is a 34-kDa glycoprotein most abundantly expressed in normal brain tissue (2, 3). When homogenates with high levels of infectivity are treated in vitro with proteinase K (PK) for a limited time, several fragments of host prion protein (PrP) remain, as well as full-length retroviral gags and other proteins (4). Protected long nucleic acids, including retroviral RNAs, can also be recovered in CJD (5), and retroviral sequences also cosediment with infectivity in scrapie (6). According to prion theory, abnormal PrP-res is itself the infectious agent in these complex preparations (7, 8). We think it more likely that abnormal PrP is part of a secondary pathologic response to high levels of infectious agent (2, 6). In SY only, and in SY mice challenged with FU (SY/FU), >95% of PrP remained normal even at very terminal stages of disease. Thus, normal PrP was not limiting. Moreover, whereas levels of infectivity were 10,000-fold different between terminal FU and SY mice, PrP-res levels were only 10-fold different (1). The PrP-res band patterns, which are supposed to distinguish strains in prion theory, were also the same in SY and FU. Such discrepancies, as well as many others (6, 9–11), have not been explained by any consistent or testable prion model.

According to prion theory, PrP-res can interact to form intermediate “chimeras” of PrP that “encode” characteristics of more than one strain (12). To test whether FU was cleared from the brain of SY-protected mice, or whether, during the long period of dual infection one could produce chimeric intermediates of SY and FU, we analyzed second passage brains from mice injected with both agents, as compared with mice injected singly with each agent (13). Two of the 18 mice inoculated with SY and later challenged with FU showed more spongiform changes and slightly higher levels of PrP-res that suggested incompletely controlled FU infection. Thus, we had a unique opportunity to evaluate a continuous mixed infection. In second passage, one of these two mice propagated FU with all its pathologic sequelae, whereas the other propagated both strains. In this case, individual recipient mice showed either FU or SY only, with no intermediate or chimeric forms as evaluated by both incubation time and lesion profiles.

Such experiments led us to conclude that (i) FU could be cleared continuously and/or completely by prior SY infection, (ii) each strain maintained its own identity during mixed infection with no intermediate or chimeric strains detectable, and (iii) the more virulent FU agent could be kept in a latent state for extended periods until some other physiologic stress allowed it to recrudesce. These findings were particularly relevant for variant CJD linked to bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), as well as other CJD infections that can be clinically silent for many years, as for example those associated with contaminated growth hormone injections. Thus, decontamination of surgical instruments and care with human biologic materials from people exposed to BSE and CJD deserved special attention (14).

To further explore the efficacy of interference, we tested lower doses of SY as well as higher doses of challenge FU agent. We also compared peripheral routes of infection. Remarkably, lower doses of SY ic that are too low to detect at the time of FU challenge were sufficient to protect all mice from FU infection until they were very old (>600 days). At this late time, mice began to die of old age without evidence of SY. In contrast, parallel control mice first inoculated with normal brain homogenates all developed FU ≈180 days after challenge. This >300-day increase in incubation time in SY-protected mice implicates powerful mechanisms of host defense and clearance that can be elicited by these exogenous infectious agents. Such effects, moreover, cannot be related to abnormal PrP, or a lack of adequate amounts of normal PrP for FU conversion, because abnormal PrP-res was not detectable in SY-protected mice.

Materials and Methods

CD-1 mice were purchased form Charles River Breeding Laboratories. Immunodeficient Rag-1/C57BL/6 (B6,129-Rag1tm1Mom) mice, maintained under pathogen-free conditions with Sulfatrim supplements, and their wild-type (wt) C57BL/6 controls were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. The origins and characteristics of SY and FU strains and their passage were as described (1, 15, 16). Titers of inocula were estimated by incubation time assays, with the calculation the effective doubling times of each agent (1, 17). To make sure every mouse in each control and challenge group received the identical infectious mix, all mice were injected with a single mixture of SY or FU on the same day in parallel for each experiment. Nine to 10 mice were designated for each experimental group. Mice were injected with 30 μl of SY or normal uninfected control brain (Nl) homogenates in the left cerebrum. Some of these mice were used as SY only or Nl only controls (8–10 each), whereas the remaining parallel groups were challenged 92 days later with FU homogenates delivered to the opposite (right) side of the brain. In an experiment where we also evaluated the serum and brain factors at 90 days, an additional 10 mice of each group had been inoculated on the same day. Peripheral i.v. injections were done via the tail vein, and the subsequent FU challenge injection used the same vein. Because preinoculation Nl brain gave the same incubation as no inoculation (13), it was omitted for the i.v. experiment; hence, 80 days are added to FU controls in Fig. 5.

Figure 5.

Interference experiment using the i.v. route. Maximal doses (10% brain homogenates) of low-passage SY and FU (SY-1/FU-1) are 193 days longer (mean ± SEM) than unprotected FU-1 controls. They were even 73 longer than 100-fold dilutions of FU (FU-3), indicating a strong suppression of FU by the i.v. route. The SY-only controls (SY-1) with more surviving mice (at 698 days) were, however, somewhat longer-lived than the SY/FU mice.

Mice were scored for signs of CJD and killed when terminal signs appeared. These signs included hunching, rough fur and slowness, or, in the case of about half the SY mice, stereotypic compulsive scratching. Half brains were stored at −70°C for Western blot PrP-res assays, with the other half used for neuropathology after 10% formalin fixation. Immunocytochemistry of pathologic PrP and other markers, such as keratin sulfate for activated microglia and glial fibrillary acidic protein, was done as described (18). A few mice died on the day of inoculation, a few were found dead, and several with very prolonged incubations began to die of old age. Nevertheless all ic groups still contained at least eight mice. In very prolonged experiments, surviving mice were killed for analysis at 659 or 698 days postinoculation.

For tests of brain factors, FU stock brain homogenate was serially diluted in 10% test brain homogenates (90-day SY, Nl, and uninoculated) to give 10−3 FU in 10−1 test brain for overnight incubation at 4°C. These mixtures were then diluted 10-fold in saline and inoculated the same day intracerebrally. Similarly, test sera were mixed with each FU brain dilution and inoculated after an incubation at 37°C for 6 h and 4°C overnight. For statistical analysis, t tests were unpaired and conservatively assumed unequal variance.

Results

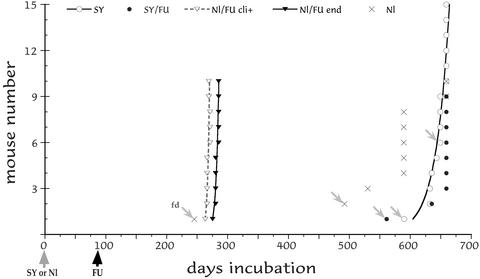

In the first ic experiment, we tested SY 4th passage brain at lower titers than previously (1) to find whether CD-1 mice could again resist challenge with FU. We also increased the interval for SY establishment from 80 to 92 days before FU challenge, to find whether protection was enhanced. Fig. 1 shows the incubation time for each mouse inoculated on the same day in parallel. Of 10 control mice inoculated only with Nl uninfected brain (×), none showed any signs of CJD, although older mice showed some scruffiness consistent with aging. Two were found dead (fd, noted by arrows), and the rest were killed at 589 and 659 days, all without CJD neuropathology. Mice inoculated with Nl brain, and then challenged with FU 92 days later, all developed clinical signs rapidly followed by terminal behavior (Fig. 1, open and filled triangles, respectively). These mice had a tight end-stage incubation of 282 ± 1.1 days (mean ± SEM). In dramatic contrast, all parallel mice given SY followed by challenge with the same dose of FU at 92 days survived >550 days (filled circles). Notably, only one of these mice showed any signs of CJD (at 635 days), and this mouse displayed compulsive scratching characteristic of SY but not FU. None of the other SY-protected mice showed any clinical signs of CJD when the experiment was terminated at 659 days. Similarly, only 4 of 15 mice inoculated in parallel with SY-only controls (open circles) showed CJD signs by 659 days. Consistent with the advanced age of SY/FU and SY-only mice, lymphomas were found in each group (3 and 2, respectively).

Figure 1.

Interference ic with low-dose SY and FU (see text). Incubation of SY-only mice (SY), SY mice challenged with FU at 92 days (SY/FU), normal brain inoculated mice challenged with FU at 92 days (Nl/FU), and mice inoculated only with normal brain on day 0 (Nl). Each inoculated mouse is shown with found dead (fd) animals indicated by arrows. Old surviving mice were killed at 659 days. All of the Nl/FU mice showed clear clinical signs (cli+, dotted curve fit) that closely followed terminal signs (Nl/FU end), whereas SY-only and SY/FU-parallel mice survived >300 days longer, and many of these showed no clinical signs or pathology.

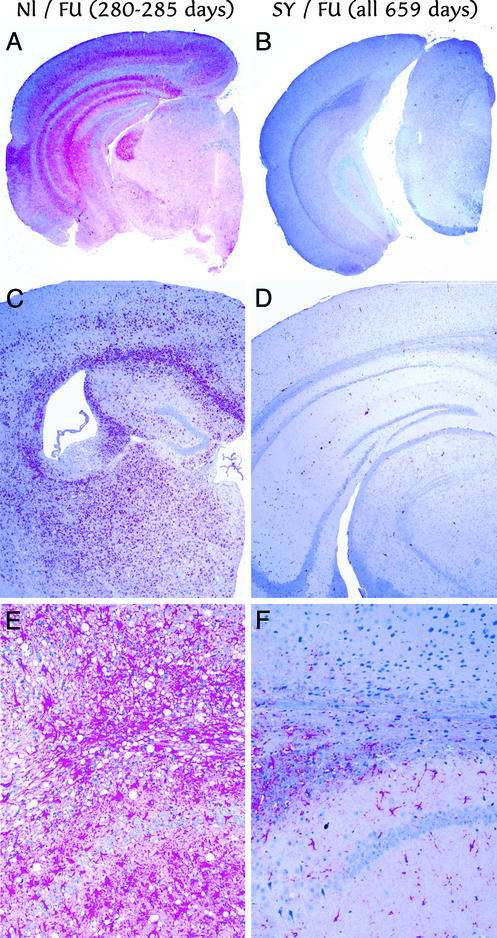

Mice inoculated with normal brain showed no remarkable histologic changes. The other brains showed either the widespread fulminant lesions of FU, or a remarkable absence of lesions that is characteristic of SY infection (13). Fig. 2 A, C, and E shows different representative brains from Nl/FU challenged mice killed at 280–285 days (equivalent to an FU challenge of ≈100 units by both clinical and terminal signs). A and B show pathologic PrP in red by low power, C and D show keratin sulfate for activated microglia, and E and F show glial fibrillary acidic protein for astrocytes. In contrast, brains from SY/FU-challenged mice (Fig. 2 B, D, and F) showed no abnormal PrP, as well as a paucity of activated microglia or astrocytic gliosis. SY-only controls, including all scratching mice in this experiment, showed the same lack of lesions, a picture often seen in many mice inoculated with low-passage SY homogenates that, nevertheless, can be transmit SY infection serially. The equivalent dose for this incubation period of SY in CD-1 mice is ≤10−4 dilution of brain or ≈20 units of this agent.

Figure 2.

(A, C, and E) Neuropathology of representative mice inoculated ic with normal brain followed by FU challenge at 92 days (Nl/FU), terminal at 280–285 days, are shown, with those first inoculated with SY (SY/FU all killed at 659 days). The low-power images in A and B show widespread pathologic PrP (red) in Nl/FU but not protected SY/FU mice. Widespread activated microglia (keratin sulfate detection, C and D) also reveals widespread microglia only in the unprotected controls. Similarly, obvious vacuolar change amidst many red hypertrophic astrocytes (glial fibrillary acidic protein detection) is seen only in Nl/FU (E) but not in SY/FU (F) mice.

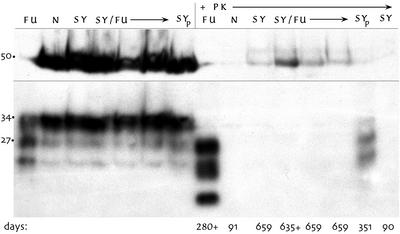

SY-infected animals, even those with terminal signs, can have undetectable levels of PrP-res by Western blotting (13). Both SY-only and SY/FU-challenged mice showed a paucity of PrP-res in subclinical, as well as scratching, sick mice. In contrast, Nl/FU-challenged mice all showed abundant PrP-res. Fig. 3 shows untreated brain homogenates from five representative mice. The first seven lanes show equivalent PrP loads without PK digestion. Aliquots of these same samples treated with PK showed little or no PrP-res in SY-only and SY/FU brains at extended incubation times, in contrast to the abundant PrP-res in Nl/FU mice (e.g., at 280 days). The low-passage terminal SY brain stock (SYp) used to infect mice in this experiment also shows PrP-res. SY brains at 90 days, just before FU challenge, also showed neither PrP-res nor any spongiform change, and were indistinguishable from Nl inoculated brains (N). Fig. 3 also shows a tubulin control for this blot (at ≈50 kDa) to confirm that SY/FU brains were not more digested than Nl/FU brains.

Figure 3.

Western blot of representative 10% brain homogenates without PK digestion (left 7 lanes) and the same samples treated with PK (+PK lanes). Each sample was 5 μl. Only the Nl/FU controls at 280 days (FU) show strong PrP-res bands, and the normal (N), SY-only (SY), and SY/FU mice show no detectable PrP-res, including the mouse at 635 days with SY clinical signs. SYp lane shows PrP-res in the early-passage SY brain, and the last SY lane shows no PrP-res in SY brains at 90 days, just before FU challenge.

The above experiment in CD-1 mice demonstrates that low doses of the relatively avirulent SY agent can completely abrogate subsequent infection by the rapidly lethal FU agent, even when the SY infection stays hidden well into senescence. The basis for this abrogation was unexplored. Most, but not all, cases of viral interference are due to the development of serum antibodies. Thus, we used parallel mice from the same experiment to evaluate (i) potential brain factors, (ii) serum components, including antibodies, and (iii) the level of SY infection at the time of challenge. Such studies could help determine whether interference was due to direct effects of reasonably high levels of the SY agent, or, whether host responses educed by this agent were more likely to underlie the FU suppression.

For assessment of infectivity, a pooled homogenate of fresh brain at 90 days after SY inoculation was inoculated into recipient mice (n = 10). From the number of SY units injected and an effective doubling time of 30 days for SY (1), one would predict three doublings of the inoculated agent. Because >90% of ic inoculated agent is rapidly cleared (17), one would predict <20 units per g of brain at 90 days, a level too low to be detected in a standard 30-μl 1% brain homogenate. Indeed, this inoculum failed to produce disease in any mice observed for >650 days. Hence, the agent itself was too low to block receptors for FU, or even to compete with higher doses of fast FU that doubles every 4.5 days. Because PrP-res was also undetectable at 90 days, lack of available cellular PrP was also insufficient to explain the strong interference effect observed.

Although we doubted that an antibody or other neutralizing factor in serum was the basis for interference, we nevertheless tested full-strength serum from SY mice at 90 days. Mixing FU homogenates to 10−5 with sequential dilution in SY sera produced no significant change in incubation time from either FU controls in sera from normal brain inoculated or uninoculated mice (mean incubations 177.6 ± 2.4, 182.2 ± 2.0, 177.9 ± 1.8 days, respectively; n = 9 each). No neuropathologic differences were seen among these mice. We also wanted to find whether cells of the brain might elaborate factors of unknown stability that could inhibit FU progression. We therefore did mixing experiments where FU was incubated with fresh brain from SY and Nl controls at 90 days, and then immediately inoculated into recipient mice. In contrast to sera mixed in parallel, SY brain significantly delayed incubation to clinical signs of FU even though there was a 10-fold higher dose of FU in these mixes (10−4 FU in 10−1 SY) than in the serum samples. Incubations for SY brain factors were significantly different from Nl inoculated or uninoculated controls (P = 0.001 and 0.0002, respectively), whereas uninoculated and Nl inoculated brain were not (P = 0.62). Mice (n = 9–10 per group) showed clinical signs at 139.9 ± 1.2 (Nl inoculated) and 138.8 ± 1.8 (uninoculated) days, whereas SY brain mixes gave an incubation of 148.1 ± 0.9 days. These data implicate the presence of at least one or more factors in SY brain that could be part of the suppressive effect. This relatively small change in incubation in direct mixing experiments would be expected, and might also be further compromised by inherent factor lability as well as endogenous brain proteases. Consistent with this idea, the interference effect was abolished when these SY samples were frozen and thawed and stored for months at −70°C (data not shown). Furthermore, factors in the homogenates would not be continuously elaborated, and additional stronger suppressive effects may be achieved by inoculation of living cells. Because microglia elaborate many factors in response to CJD (19, 20), it will be of interest to test the suppressive effects of these cells experimentally.

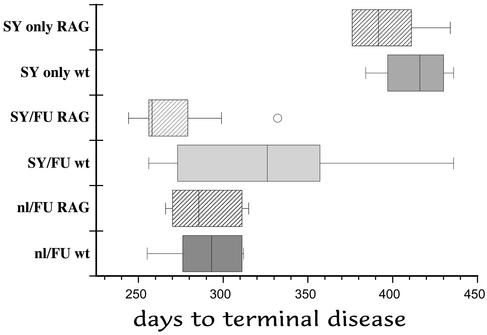

To further evaluate the role of lymphoid cells in interference, we used wt C57BL/6 and immunodeficient Rag-1 mice on the same genetic background. In this experiment, we also tried higher doses of FU, as well as SY that had been serially passaged three additional times. With passage, SY can evolve to produce lesions more rapidly (18). With these modifications, the time to clinical signs in Nl/FU mice was 26 days shorter than in the Nl/FU controls in Fig. 1, indicating a 10- to 100-fold increase in the FU challenge dose. The SY homogenate also gave an ≈50-day shorter incubation time than lower passage SY homogenates at the same dose (1), indicating enhanced virulence. In this experiment, mice did not show a clear or obvious interference effect. Fig. 4 shows box plots (8–10 mice scored per group), with the median line indicated. The SY-only and FU-challenged mice were significantly different (P < 0.0001) whereas the SY/FU Rag-1 mice showed no interference. All of these mice, with the exception of one longer lived outlier (circle), overlapped incubations of the Nl/FU controls. The wt SY/FU mice, however, showed a much larger spread of incubation times (Fig. 4, SY/FU wt). This group of mice did not show a normal Gaussian distribution, but rather two well separated groups on each side of the median (256–305 and 347–436 days, n = 4 each). These two groups of mice were significantly different from each other (P = 0.016), and those above the median were different from all of the other Nl/FU controls (P ≤ 0.02). Those below the median were indistinguishable from the other FU controls (P = 0.53–0.66). Therefore, although FU overwhelmed SY protection in most challenged mice, there still seemed to be limited or aborted protection by SY in some wt mice. More experiments will be required to rule out any lymphoid cell effect.

Figure 4.

Box plot of incubation times with higher doses of FU and later passaged SY in WT and RAG-1 mice. Median is shown by line in each box, and the circle represents an outlier mouse. Interference is completely abolished except in the SY/FU wt mice above the median (see text).

To further clarify whether SY/FU wt mice were partially protected, we further evaluated their neuropathology, the most accurate way to distinguish SY from FU. Several SY/FU-challenged wt mice, particularly those above the median, showed evidence of a mixed SY/FU infection with incomplete FU lesions. In this case, the widespread PrP abnormalities as shown in Fig. 2A were not present, and instead only scattered deposits of pathological PrP were found. These mice also showed more focal vacuolar changes in contrast to the widespread lesions of complete FU. Additionally, one of these SY/FU wt mice (dying at 436 days) showed a pattern of SY. In summary, higher dose of FU, combined with enhanced virulence of the SY inoculum, compromised but did not completely abolish the interference effect. Nevertheless, both the precise balance of agent doses, as well as the particular properties of the slow agent, are crucial for complete or sustained interference.

We additionally tested the interference ability of earlier passaged SY by using a peripheral i.v. route for both protection and challenge. We used this route because the challenge dose would be limited to the discrete pathways first encountered by SY, and blood can also be a conduit for these CJD agents (21–25). In this experiment, we used an 80-day interval between SY and FU challenge because peripheral inoculations are less efficient and yield longer incubation times. We therefore also inoculated maximal doses of both SY and FU (100 μl each of 10−1 brain homogenates). Fig. 5 shows that SY mice challenged with 10−1 FU had a dramatically longer incubation period, by 193 days, than unprotected mice with the same dose of FU (P < 0.0001). Remarkably, the incubation period in the SY-protected mice was also longer by 73 days than that of FU controls diluted 100-fold more (to 10−3, P < 0.0017). The smaller difference between SY-only and SY/FU (P = 0.034) may be due to late escape of FU, similar to that documented in past ic interference experiments (13). Histologically, the SY-only group also contained mice dying of old age rather than SY, as in Fig. 1. Some FU/SY mice showed SY only, others had a mixed infection with minimal FU lesions, and one showed a widespread complete FU pattern, indicating earlier escape of FU in this one mouse. Because so many different peripheral cell types may carry these agents, we were surprised to find that the i.v. route yielded such an obvious and strong interference effect.

Discussion

These data demonstrate a complete and dramatic prevention of a virulent form of CJD by prior injection of an attenuated agent. It is further remarkable that the attenuated SY agent, when given in low doses, may never seem to produce disease, even in very old mice. This suppression is more complete and extensive than that previously demonstrated, and there was an absence of disease for ≈2 years after initial infection with SY. FU was suppressed for ≈1 year, greater than any pharmacologic prevention reported with an ic route of infection. A strong interference effect was also obtained by using the i.v. route, even after maximal doses of challenge FU agent.

This result raises the question of whether people commonly harbor an attenuated CJD agent that makes them less susceptible to low-challenge doses of more virulent CJD agents, such as those linked to BSE. The newly virulent BSE agent was consumed by millions of people in multiple small doses, with others probably exposed iatrogenically to the human adapted form (14), yet relatively few people have developed BSE-linked disease over the past 15 years (currently 121 cases). Interestingly, injection of normal human blood samples can produce some vacuolar change in first-passage recipient animals, but all 40 recipients tested were incapable of propagating a serial pathogenic infection (6, 26). These data could be consistent with widespread human infection by an agent of very low virulence that evokes a clearance response, or remains latent, much like the minimal SY infection or iatrogenic growth hormone infections that can remain hidden for >30 years after exposure. As in the low-passage SY infections here, people with clinical symptoms of sporadic CJD may also show undetectable levels of pathologic PrP (27). Notably, suppression of FU in interference experiments was not based on any detectable PrP changes, and susceptibility to these agents therefore entails far more than just host PrP sequence or its conformation. PrP also has no comparable suppressive capacity in vivo because “vaccination” with multiple doses of PrP antibodies before scrapie infection produced only a small effect on incubation time (8–18 days) and no effect on vacuolar lesions or PrP-res development (35). Simple brain mixing experiments gave a comparable prolongation here.

Despite the strong 200- to >300-day abrogation of disease in several independent experiments, we have also shown that suppression can be overcome by higher doses of agent. This finding, as well as the inherent danger of using a competent infectious agent for prevention, makes vaccination with an attenuated CJD agent a poor strategy for epidemic control of these infections. Despite their extraordinary latency, these agents can be activated and escape from their hidden reservoirs to cause lethal disease. It is therefore more fruitful to consider mechanisms underlying suppression that can have therapeutic and/or preventive application. We found unrecoverable levels of the avirulent SY agent at the time of FU challenge, and thus direct agent competition is not necessary for a complete interference effect. This observation further excludes competition of two agents for “limited replication sites” (28), as well as insufficient cellular PrP docking or receptor sites needed for completion of the agent's life cycle (29). Effective interference also does not involve simple competition between two agents where the faster one will always win out, unless it is given in miniscule doses relative to huge doses of slow agent. The FU controls showed rapid and robust replication, whereas the same FU dose was inhibited in the face of clinically and pathologically covert SY.

Serum was not able to mimic the suppressive effect, a finding consistent with the well-known failure of these agents to elicit neutralizing antibodies. However, fresh SY brain seemed to contain some suppressive labile factors that prolonged the incubation time. Other studies in our laboratory further confirm the elaboration of particular inflammation-related molecules in the brain during CJD infection (19, 20), and some of these molecules are likely to be involved in the suppression of FU seen here. Notably, these molecules are elaborated by microglial cells in response to infection, but most of them could not be educed by PrP-res-enriched brain fractions. Furthermore, these microglial cells, as well as peripheral macrophages and dendritic cells, were found to carry reasonably high levels of CJD and scrapie infectivity (30, 31). Many different viruses classically hide in myeloid cells, and some can be carried in a latent state or inactivated by host factors elaborated in defense (32). This finding tightens the connection between brain factors elicited by CJD infection and mechanisms of suppression and clearance. Other cell types may produce additional factors that are additive. Indeed, innate immunity is the first line of defense against viruses, and often involves cytokines (32, 33) and IFN pathways (34). Both of these pathways are recruited in CJD-infected microglia (20). In short, we propose that mechanisms of innate immunity are central to the strong interfering effects observed. The host obviously recognizes and responds to the foreign CJD agent in a way that seems to be unrelated to any version of PrP. In principle, it should be possible to artificially stimulate relevant myeloid pathways to better prevent and/or delay the clinical and pathological sequelae of these infections. It will also be of interest to test interference in different cell types in vitro to elucidate the spectrum of humoral and cellular defense mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ion Gresser for input on design of serum and brain factor experiments, Bill Fritch for preparation of low-passage SY and serum/brain factor material, Mark Cherynak for help with the histology, and members of our laboratory for their participation in animal observations. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants NS12674 and NS34569.

Abbreviations

- CJD

Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease

- ic

intracerebral

- BSE

bovine spongiform encephalopathy

- PK

proteinase K

- PrP

host prion protein

- PrP-res

PrP after limited PK digestion

- Nl

normal

- SY

slow CJD agent

- FU

fast CJD agent

- wt

wild type

References

- 1.Manuelidis L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2520–2525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manuelidis L, Valley S, Manuelidis E E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:4263–4267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.12.4263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oesch B D, Westaway D, Wälchli M, McKinley M P, Kent S B, Aebersold R, Barry R A, Tempst P, Teplow D E, Hood L E, et al. Cell. 1985;40:735–746. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90333-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manuelidis L. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1994;724:259–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb38916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akowitz A, Sklaviadis T, Manuelidis L. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:1101–1107. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.6.1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manuelidis L. Nova Acta Leopoldina. 2002;87:91–110. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prusiner S B. Science. 1982;216:136–144. doi: 10.1126/science.6801762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prusiner S, Baldwin M, Collinge J, DeArmond S, Marsh R, Tateishi J, Weissmann C. In: Prions, Virus Taxonomy. Murphy F, Fauquet C M, Bishop D H L, Ghabrial S A, Jarvis A W, Martelli G P, Mayo M A, Summers M D, editors. Vienna: Springer; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manuelidis L, Sklaviadis T, Akowitz A, Fritch W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5124–5128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.5124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xi Y G, Ingrosso A, Ladogana A, Masullo C, Pocchiari M. Nature. 1992;356:598–601. doi: 10.1038/356598a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lasmezas C, Deslys J-P, Robain O, Jaegly A, Beringue V, Peyrin J-M, Fournier J-G, Hauw J-J, Rossier J, Dormont D. Science. 1997;275:402–405. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5298.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scott M, Groth D, Tatzelt J, Torchia M, Tremblay P, DeArmond S, Prusiner S. J Virol. 1997;71:9032–9044. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9032-9044.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manuelidis L, Lu Z Y. Neurosci Lett. 2000;293:163–166. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manuelidis L. J Neurovirol. 1997;3:62–65. doi: 10.3109/13550289709015793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manuelidis E E, Gorgacz E J, Manuelidis L. Nature. 1978;271:778–779. doi: 10.1038/271778a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manuelidis L, Murdoch G, Manuelidis E. Ciba Found Symp. 1988;135:117–134. doi: 10.1002/9780470513613.ch8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manuelidis L, Fritch W. Virology. 1996;215:46–59. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manuelidis L, Fritch W, Xi Y G. Science. 1997;277:94–98. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5322.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker C A, Martin D, Manuelidis L. J Virol. 2002;76:10905–10913. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.21.10905-10913.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baker C, Manuelidis L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:675–679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0237313100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manuelidis E E, Gorgacz E J, Manuelidis L. Science. 1978;200:1069–1071. doi: 10.1126/science.349691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manuelidis E E, Kim J H, Mericangas J R, Manuelidis L. Lancet. 1985;ii:896–897. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)90165-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tateishi J. Lancet. 1985;ii:1074. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)90949-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Radebold K, Chernyak M, Martin D, Manuelidis L. BMC Infect Dis. 2001;1:20–25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-1-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shlomchik M, Radebold K, Duclos N, Manuelidis L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9289–9294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161055198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manuelidis E E, Manuelidis L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7724–7728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manuelidis L, Manuelidis E E. Prog Med Virol. 1985;33:78–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dickinson A, Fraser H, Meikle V, Outram G. Nat New Biol. 1972;237:244–245. doi: 10.1038/newbio237244a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Büeler H, Aguzzi A, Sailer A, Greiner R-A, Autenried P, Auget M, Weissmann C. Cell. 1993;73:1339–1347. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90360-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manuelidis L, Zaitsev I, Koni P, Lu Z-Y, Flavell R, Fritch W. J Virol. 2000;74:8614–8622. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.18.8614-8622.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aucouturier P, Geissmann F, Damotte D, Saborio G, Meeker H C, Kascsak R, Kascsak R, Carp R I, Wisniewski T. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:703–708. doi: 10.1172/JCI13155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chowdhury I H, Bentsman G, Choe W, Potash M J, Volsky D J. J Neurovirol. 2002;8:599–610. doi: 10.1080/13550280290100923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guidotti L G, Chisari F V. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:65–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nguyen M D, Julien J-P, Rivest S. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:216–227. doi: 10.1038/nrn752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sigurdsson E M, Sy M S, Li R, Scholtzova H, Kascsak R J, Kascsak R, Carp R, Meeker H C, Frangione B, Wisniewski T. Neurosci Lett. 2003;336:185–187. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)01192-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]