Abstract

The tumor suppressor p53 is regulated in part by binding to cellular proteins. We used p53 as bait in the yeast two-hybrid system and isolated homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 1 (HIPK1) as a p53-binding protein. Deletion analysis showed that amino acids 100–370 of p53 and amino acids 885-1093 of HIPK1 were sufficient for HIPK1–p53 interaction. HIPK1 was capable of autophosphorylation and specific serine phosphorylation of p53. The HIPK1 gene was highly expressed in human breast cancer cell lines and oncogenically transformed mouse embryonic fibroblasts. HIPK1 was localized to human chromosome band 1p13, a site frequently altered in cancers. Gene-targeted HIPK1−/− mice were grossly normal but oncogenically transformed HIPK1 −/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts exhibited reduced transcription of Mdm2 and were more susceptible than transformed HIPK1+/+ cells to apoptosis induced by DNA damage. Carcinogen-treated HIPK1 −/− mice developed fewer and smaller skin tumors than HIPK1+/+ mice. HIPK1 may thus play a role in tumorigenesis, perhaps by means of the regulation of p53 and/or Mdm2.

The most frequently mutated gene associated with human cancers is p53 (1, 2). In response to cellular stresses such as DNA damage and oncogene expression, p53 promotes cell-cycle arrest or apoptosis (3, 4). p53 stabilization and activity are regulated by conformational changes (3) and posttranslational modification by phosphorylation (5). However, the kinase(s) relevant for phosphorylation of p53 in vivo remain obscure. p53 activity is also regulated by interaction with cellular molecules such as the oncogenic protein Mdm2 (2). Overexpression of Mdm-2 in certain tumors results in the inactivation and degradation of p53 (6–10). We set out to identify proteins that interact with p53 and to examine the expression of these molecules in transformed cells. We isolated the p53-binding kinase homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 1 (HIPK1), previously identified as a homeodomain-interacting protein (11), and analyzed p53–HIPK1 interaction by various means. The physiological functions of HIPK1 were characterized by using gene-targeted HIPK1-deficient mice. Our in vivo and in vitro characterizations of HIPK1 suggest that HIPK1 is a modulator of p53 activity that can promote oncogenesis.

Methods

Yeast Two-Hybrid Screening.

A human p53 cDNA (amino acids 71–393; ref. 12) was subcloned in-frame into pGBT9 (GAL4 DNA-binding domain vector) and used to screen cDNA libraries constructed by using pGAD424 (GAL4-activation-domain plasmid; ref. 13) in yeast Y2H strain SFY526. The libraries were derived from rat embryo fibroblasts transformed with E1A + Ras + mutant p53 R273H, and a breast cancer cell line. β-Galactosidase activities were measured by using the Galacto-Light reporter assay kit (Tropix, Bedford, MA). The cDNA plasmids from β-galactosidase-positive yeast were rescued, retested in yeast, and sequenced.

Interaction of HIPK1 with p53 in 293 Cells.

The SalI/NotI HIPK1 fragment corresponding to amino acids 678-1149 was ligated in-frame with either a Myc tag in the pRc/CMV vector or a His tag in the pEBVHis vector (Invitrogen). Human 293 cells expressing endogenous p53 were transfected with the myc-HIPK1 expression plasmid by using Lipofectamine (GIBCO/BRL). After 48 h, lysate supernatants were immunoprecipitated by using anti-p53 antibody (DO-1; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) conjugated to agarose beads. The supernatants were immunoblotted by using anti-myc antibody (Oncogene Science) and visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Amersham Biosciences).

Isolation of Full-Length Human and Mouse HIPK1 cDNAs and p53–HIPK1 Interaction Domains.

Using the rat cDNA as a probe, we cloned full-length human HIPK1 (1210 aa) was cloned from a skeletal muscle Stretch Plus lambda gt11 library (BD Biosciences Clontech), and full-length mouse HIPK1 was cloned from the RNA of transformed mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). Deletion mutations of the p53 and HIPK1 genes were created by using standard PCR protocols and were used to map their interaction domains. p53 deletions were cloned into EcoRI/SalI sites in pGBT9 and HIPK1 deletions were cloned into EcoRI/SalI sites of pGAD424. The DNA sequences were confirmed and the mutants were tested in Y2H.

Northern Blot Analyses.

Tissue distribution of WT HIPK1 expression was examined by using a commercial human tissue RNA blot (BD Biosciences Clontech). For all other Northern blots, 20 μg of total RNA isolated from primary or transformed cells of mouse or human origin by the TRIzol method (GIBCO/BRL) was used. Blots were prepared by using standard protocols and hybridized to the following probes: full-length human or mouse HIPK1 cDNAs; mdm-2 cDNA (base pairs 562-1197); full-length mouse p21 cDNA; and mouse TSP-1 cDNA (base pairs 941-2092).

Kinase Assays of HIPK1 Expressed in COS Cells.

pcDNA3.1DNA/Zeo plasmids (Invitrogen) containing the control HA sequence or the HA-tagged full-length murine HIPK1 cDNA were transfected into COS cells by using Lipofectamine-plus reagents (GIBCO/BRL). Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody (Invitrogen), suspended in kinase buffer (40 mM Hepes/10 mM MgCl2/3 mM MnCl2) with 1 μg of GST-fused p53 protein (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and incubated with 10 μM [γ-32P]ATP for 30 min. The mixture was boiled, resolved by electrophoresis, and visualized by autoradiography.

Comparative Phosphopeptide Analysis of p53.

Transformed HIPK1+/+ and −/− MEFs were labeled in 150-mm dishes for 3 h with 5 mCi (1 Ci = 37 GBq) of [32P]orthophosphate. p53 was isolated from cell extracts by immunoprecipitation with anti-p53 Ab-4 antibody (Oncogene Science). Immunoprecipitated proteins were fractionated by SDS/PAGE and subjected to trypsin digestion and phosphopeptide and phosphoamino acid analysis as described (14).

Generation of HIPK1−/− Mice.

Genomic clones of HIPK1 DNA were isolated from a 129J mouse library by using the rat cDNA probe. A targeting vector was constructed by using pBluescript II KS(+) (Stratagene), which replaced 2.7 kb of genomic DNA containing the first exon of HIPK1 (encoding the putative kinase domain) with a neomycin-resistance cassette inserted in sense orientation to HIPK1 transcription. The targeting vector was electroporated into E14K embryonic stem (ES) cells. After G418 selection (GIBCO/BRL), homologous recombinants were identified by PCR and confirmed by Southern blotting. Four clones heterozygous for the targeted mutation were injected into 3.5-day-old C57BL/6 blastocysts and transferred into pseudopregnant foster mothers. Chimeric mice were crossed into C57BL/6 mice to generate heterozygous mice, which were intercrossed to produce HIPK1−/− mice. Genotypes were confirmed by Southern blotting of tail DNA. For the generation of HIPK1−/− ES cell lines, G418-resistant HIPK1+/− ES clones were cultured at an increased concentration of G418 (1.2 mg/ml) and analyzed by Southern blotting.

Retrovirus-Mediated Gene Transfer.

Ectopic retroviruses were produced by using the Phoenix packaging line (generously provided by G. Nolan, Stanford University, Stanford, CA). The retroviral vectors were pLPC-12S, which coexpresses 12S E1A cDNA with puromycin phosphotransferase, and pWZL-Ras/CD8, which coexpresses human H-Ras V12 cDNA with the CD8 cell-surface marker. WT and HIPK1−/− MEFs were infected first with pLPC-12S and cells were selected in medium containing 2.5 μg/ml puromycin (Sigma). Puromycin-resistant cells were then infected with pWZL-Ras/CD8 and transformed cells were recovered with magnetic beads conjugated to anti-CD8 (Dynal, Great Neck, NY).

Colony Transformation, Apoptosis, and Reintroduction of HIPK1.

For colony transformation assays, cells were suspended in 0.4% low-melting agarose in DMEM containing 10% FCS and plated on solidified 0.53% agarose at 1 × 103 cells per well on six-well plates. Colony numbers were scored after 10 days. For apoptosis assays, transformed MEFs (1 × 105 per well) were plated in six-well plates and treated for 24 h with doxorubicin (0.2 μg/ml), etoposide (1 μM), or γ-irradiation (20 Gy). Cell viability was determined by negative staining for the vital dye 7-aminoactinomycin D followed by flow cytometry. For the reintroduction of HIPK1 into HIPK1−/−-transformed MEFs, cells were electroporated with pcDNA3.1/Zeo vector containing HIPK1 cDNA or the control hemagglutinin (HA) sequence and selected in medium containing 0.3 mg/ml zeocin (Invitrogen).

Luciferase Assays and Western Blots.

HIPK1+/−- and −/−-transformed MEFs (1 × 106 cells per 10-cm dish) were transiently cotransfected by electroporation with 5 μg of Mdm2-luciferase reporter plasmid plus 5 μg of GFP plasmid (for normalization of transfection efficiency). The Mdm2-luciferase reporter plasmid contained the intronic Mdm2 ApaI/NsiI fragment, which has two p53-binding motifs (15). The p21 luciferase reporter plasmid contained 20 base pairs of the 5′ p53 response element of the human p21 gene (16). Luciferase activities were determined 48 h after electroporation by the Luciferase Assay system (Promega). Western blots were performed by using standard protocols. Antibodies used were as follows: CM5 (Novocastra, Newcastle upon Tyne, U.K.) for p53; 2A10, provided by G. Zambetti, St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, Memphis, TN, for Mdm2; and anti-β-actin (Sigma). For evaluation of p53 status, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with either PAb240 (anti-mutant p53; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or PAb246 (anti-WT p53; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and immunoblotted with biotinylated PAb240 antibody (Oncogene Research Products, San Diego).

(7,12-Dimethylbenz[a]anthracene) DMBA-Induced Skin Papilloma Formation.

Two independent experiments were carried out. Experiment 1 involved 8 HIPK1+/+, 11 HIPK1+/−, and 13 HIPK1−/− mice, whereas experiment 2 involved 11 HIPK1+/− and 10 HIPK1−/− mice. The backs of 8-week-old mice were shaved and painted with 10 μg of DMBA (Sigma) in 0.2 ml of acetone once a week for a period of 14 (experiment 1) or 17 weeks (experiment 2). Scoring for tumors was done once a week. All mice were killed at 14 (experiment 1) or 17 weeks (experiment 2) and representative organs (including skin) were examined histopathologically.

Results

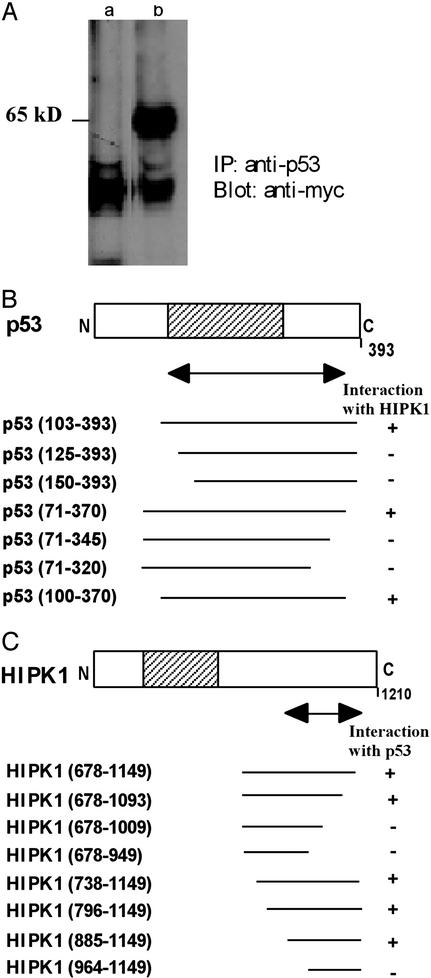

When human WT p53 (amino acids 71–393) was used as bait in a yeast two-hybrid assay (13) to screen a transformed rat-embryonic-fibroblast cDNA library, a previously undescribed kinase, HIPK1, was identified. Human 293 cells expressing endogenous p53 were then transfected with a plasmid expressing a Myc-tagged HIPK1 fusion protein expressing amino acids 678-1149 of human HIPK1, or with empty Myc-vector. In immunoprecipitation experiments, a distinct protein band at 65 kDa was observed only in extracts of cells transfected with the Myc-HIPK1 vector (Fig. 1A), indicating that HIPK1 can form a stable intracellular complex with p53. Sequence analysis of the full-length human HIPK1 cDNA showed that the HIPK1 protein contains a putative serine-threonine kinase domain (17), and in situ hybridization revealed that HIPK1 localizes to human chromosome band 1p13, a region frequently altered in human breast cancers (ref. 18; data not shown). Deletion analyses using yeast two-hybrid assays showed that a 271-aa region of p53 spanning amino acids 100–370 was sufficient for association with HIPK1 (Fig. 1B). This region overlaps the p53 domain known to be involved in binding to specific DNA sequences but does not include the p53-transactivation domain or the nonspecific DNA-interaction domain (12). A region of HIPK1 spanning amino acids 885-1093 (which does not include the kinase domain) was found to be necessary for binding to p53 (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Interaction between p53 and HIPK1. (A) Interaction of HIPK1 with p53 protein in mammalian cells. Myc alone (lane a) or Myc-tagged HIPK1 (lane b) was transfected into human 293 cells expressing endogenous p53, and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-p53 Ab. Immunoprecipitates were then immunoblotted by using anti-Myc Ab. (B) Deletion analysis of the p53 interaction domain as determined by binding to HIPK1 in a yeast two-hybrid assay. (C) Deletion analysis of the HIPK1-interaction domain as determined by binding to p53 in a yeast two-hybrid assay. For B and C, the amino acid numbers in parentheses indicate the section of p53 or HIPK1 present in the fusion protein. The double-headed arrow indicates the minimum interaction-domain required in each case. Shaded areas indicate the sequence-specific DNA-binding domain of p53 (B) and the kinase domain of HIPK1 (C).

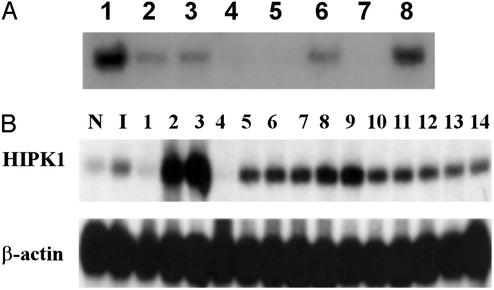

High-stringency Northern blot analysis revealed that the ≈9 kb of HIPK1 mRNA was expressed in heart, brain, placenta, skeletal muscle, and pancreas (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, in 12 of 14 human breast cancer cell lines tested, HIPK1 mRNA was elevated, compared with levels in normal mammary epithelial cells and a nontumorigenic cell line (Fig. 2B). In two of these cell lines (MCF7 and BT20-T), HIPK1 was expressed at >10 times control levels, suggesting that HIPK1 might be an oncogene.

Figure 2.

Northern blot analysis of HIPK1 transcripts in normal and transformed cells. (A) Northern blot of HIPK1 expression in human tissues. Lanes 1–8 are heart, brain, placenta, lung, liver, skeletal muscle, kidney, and pancreas, respectively. (B) HIPK1 expression in various human breast cancer cell lines. N, normal breast epithelial cells; I, nontumorigenic breast epithelial cell line (HBL-100). Breast cancer cell lines: ZR75–1, MCF7, BT20-T, DU-475, ZR-75–30, MDA-MB-361, MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-468, BT-20, SK-BR-3, T47D, MDA-MB-231-B3, MDA-MB-231–453, and HS0578T (lanes 1–14).

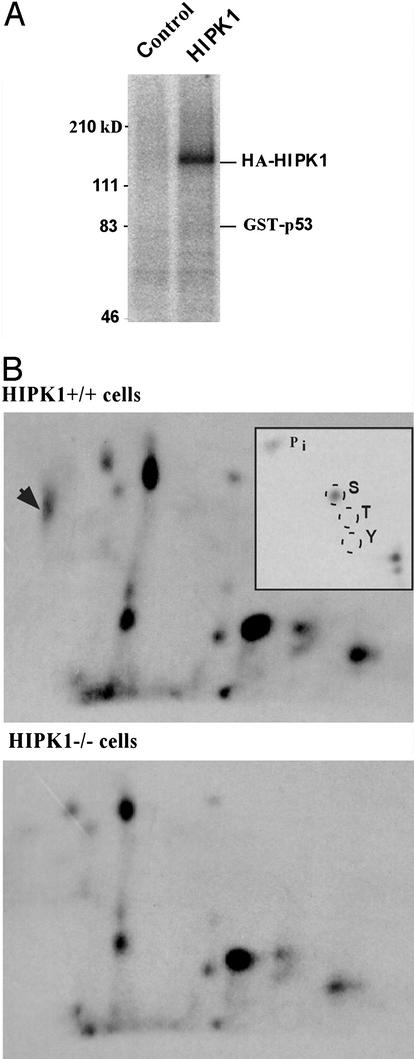

We next investigated whether HIPK1 phosphorylated p53. HIPK1 protein immunoprecipitated from lysates of COS cells in which murine HIPK1 was transiently expressed were subjected to in vitro kinase assays using p53 as substrate. The results showed that, in vitro, HIPK1 was able to phosphorylate itself, but not p53 (Fig. 3A). Because the phosphorylation of p53 by HIPK1 might require a cellular context, we looked at the phosphorylation status of p53 in transformed MEFs generated from either HIPK1+/+ or HIPK1−/− mice (see below). After labeling of MEFs with 32P in vivo, lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-p53 antibody and the electrophoresed p53 band was isolated and subjected to tryptic phosphopeptide analysis. The presence of HIPK1 led to the appearance of a unique phosphopeptide spot that was absent in cells lacking HIPK1 (Fig. 3B). Phosphoamino acid analysis of this spot revealed phospho-serine exclusively (Fig. 3 B Inset). The relative mobility of the HIPK1-induced phosphopeptide was consistent with its being the multiply phosphorylated N-terminal 27-aa tryptic peptide of p53 identified in previous reports (19, 20). Thus, HIPK1 can induce serine phosphorylation of p53 in vivo.

Figure 3.

Autophosphorylation of HIPK1 and in vivo induction of p53 phosphorylation by HIPK1. (A) Autoradiograph showing in vitro kinase activity of HA-tagged murine HIPK1 (HA-HIPK1) using GST-p53 as the substrate. (B) Tryptic phosphopeptide analysis of p53 isolated from metabolically 32P-labeled E1A/Ras transformed HIPK1+/+ and HIPK1−/− cells. The arrowhead indicates an additional p53 phosphopeptide present in HIPK1+/+ cells, and Inset shows the phosphoamino acid composition of this peptide.

To determine the physiological role of HIPK1, HIPK1-deficient mice were created by conventional gene targeting (see Methods). The genotypes of HIPK1+/− and HIPK1−/− mice were confirmed by Southern analysis and deletion of HIPK1 was confirmed by Northern analysis of RNA from primary MEFs and ES cells (data not shown). HIPK1−/− mice were born at the expected Mendelian frequency, displayed no gross abnormalities of growth or development, and were fertile. No spontaneous tumors were observed in HIPK1−/− mice over a 1-yr period.

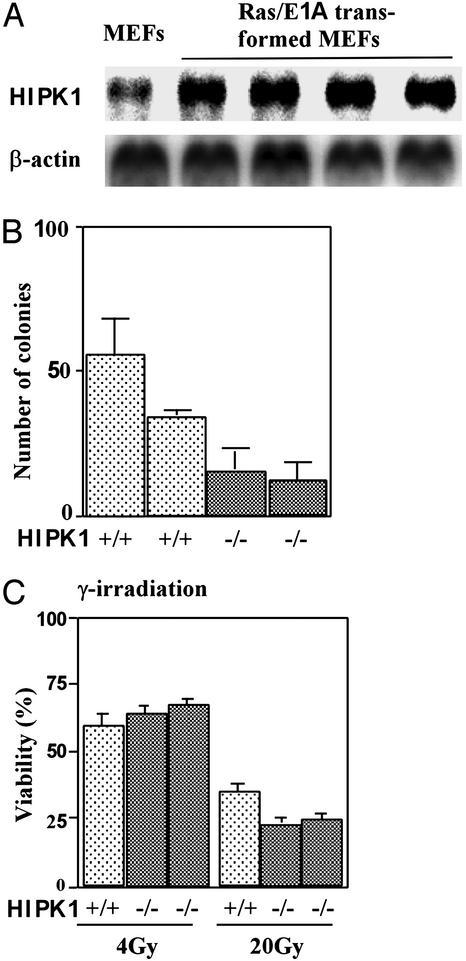

To examine the role of HIPK1 in oncogenesis, E1A and H-Ras oncogenes (E1A/Ras) were introduced into HIPK1+/+ and HIPK1−/− primary MEFs by retroviral gene transfer (21). Cellular transformation was achieved in both cases, as determined by tumor formation in nude mice (data not shown). Expression of HIPK1 was increased in four independent clones of E1A/Ras-transformed HIPK1+/+ MEFs compared with nontransformed WT MEFs (Fig. 4A). In colony-formation assays in semisolid medium, HIPK1−/−-transformed MEFs formed 2-fold fewer colonies than HIPK1+/+-transformed MEFs, and 20-fold fewer than p53−/−-transformed MEFs (Fig. 4B and data not shown). Thus, the presence of HIPK1 enhances malignant transformation by E1A/Ras.

Figure 4.

DNA-damage-induced apoptosis in transformed MEFs. (A) Northern blot analysis of mouse HIPK1 transcripts in E1A/Ras-transformed MEFs. (B) Colony formation assay. The mean number ± SD of colonies formed in triplicate experiments by two independent clones each of HIPK1+/+- and HIPK1−/−-transformed MEFs is shown. (C) Apoptosis of transformed MEFs induced by γ-irradiation at the indicated doses. Comparable results for experiments in B and C were obtained in three independent trials.

In primary HIPK1−/− MEFs and thymocytes, DNA damage triggered normal p53-dependent cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis (data not shown). However, when HIPK1−/−-transformed MEFs were treated with high doses of γ-irradiation (20 Gy; Fig. 4C), doxorubicin (0.2 μg/ml), or etoposide (1 μM) (data not shown), apoptosis was increased. These results imply that HIPK1 is involved in regulating apoptosis caused by DNA damage in oncogenically transformed cells.

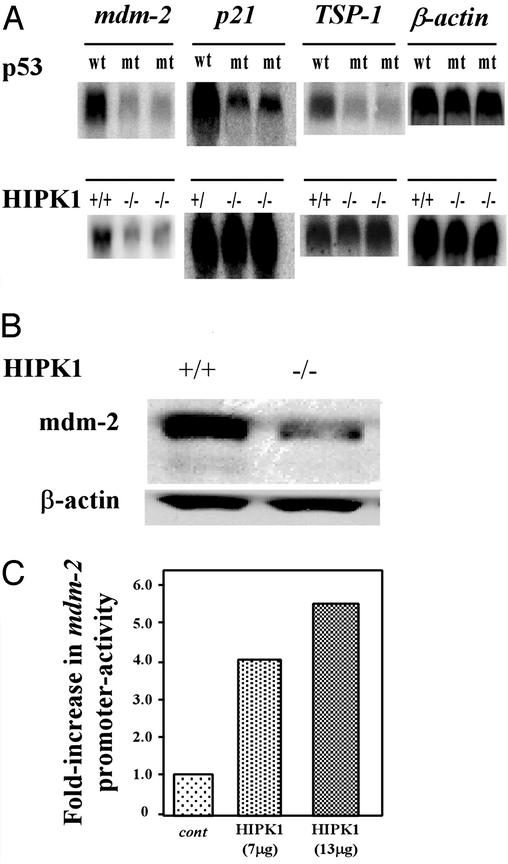

To investigate whether HIPK1 modulates the transcriptional activity of p53, we carried out Northern blot analyses of the expression of the p53-inducible genes Mdm-2, p21, and thrombospondin 1 (TSP1) in oncogenically transformed MEFs. As controls, we used two lines of E1A/Ras-transformed MEFs expressing a spontaneous mutation of p53 that were established in our laboratory; these cells are functionally null for p53. As expected, basal levels of Mdm2, p21, and TSP-1 transcripts all were decreased in transformed MEFs expressing mutant p53 compared with transformed MEFs expressing WT p53 (Fig. 5A Upper). However, in oncogenically transformed HIPK1−/− MEFs expressing WT p53, basal levels of both Mdm2 transcripts (Fig. 5A Lower) and protein (Fig. 5B) were decreased, whereas basal expression of p21 and TSP1 transcripts was unaffected (Fig. 5A Lower). Luciferase reporter assays (see Methods) showed that the Mdm2 promoter was less active (42.2% of WT value) in HIPK1−/−-transformed MEFs than in HIPK1+/+-transformed MEFs, whereas the p21 promoter was transactivated to a similar degree in cells of both genotypes (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, when full-length mouse HIPK1 cDNA was transiently transfected into HIPK1−/−-transformed MEFs and luciferase activity was determined, a 4- to 6-fold increase in Mdm2 promoter activation was observed (data not shown). Thus, expression of the p53 target gene Mdm2 is influenced at the transcriptional stage by HIPK1.

Figure 5.

Expression of p53-inducible genes in transformed MEFs. (A) Basal expression of Mdm2, p21, and TSP-1 transcripts in transformed MEFs. (Upper) Transformed MEFs expressing either WT or mutant (mt) p53. (Lower) Transformed MEFs either expressing or lacking HIPK1. Comparable results were obtained by using three other independently generated HIPK1−/− clones. (B) Western blot analysis of Mdm2 protein in transformed MEFs. (C) Mdm2 promoter activity. The indicated amounts of pcDNA3.1/Zeo plasmids containing either the control HA sequence (cont) or full-length mouse HIPK1 cDNA (HIPK1) were electroporated into HIPK1−/−-transformed MEFs. A plasmid containing the luciferase gene under the control of the Mdm2 promoter was used as the reporter. Luciferase activity is represented as the fold increase in transactivation relative to samples transfected with reporter constructs and control parental plasmids.

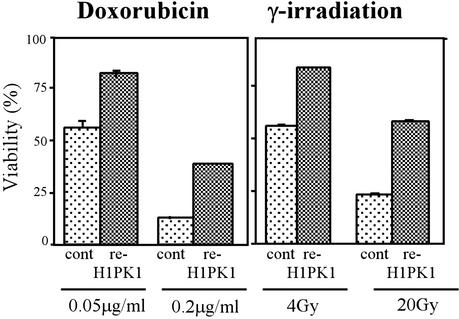

To confirm that loss of HIPK1 was responsible for the phenotype of transformed HIPK1−/− MEFs, we generated stably transfected “reintroduced HIPK1 ” (re-HIPK1) cell lines by using the full-length mouse HIPK1 cDNA and Zeocin selection (see Methods). The reintroduction of HIPK1 into HIPK1−/−-transformed MEFs increased the expression of Mdm2 transcripts over that in controls (data not shown) and restored resistance to doxorubicin and γ-irradiation (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Restoration of apoptosis after stable reintroduction of HIPK1 into HIPK1−/−-transformed MEFs. pcDNA3.1/Zeo plasmids containing either the control HA sequence or the full-length mouse HIPK1 cDNA were electroporated into HIPK1−/−-transformed MEFs followed by Zeocin selection. Apoptosis of transformed MEFs induced by the indicated doses of doxorubicin or γ-irradiation is shown.

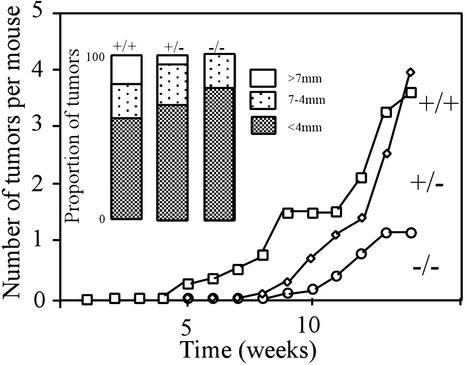

To examine the role of HIPK1 in oncogenesis in vivo, mice were treated with repeated applications of the skin carcinogen DMBA (22, 23). After 14 weeks, fewer (Fig. 7) and smaller (Inset) tumors had developed on the skin of treated HIPK1−/− mice than on that of heterozygous or WT littermates. Mean tumor numbers were as follows: 1.3 tumors per HIPK1−/− mouse (n = 13); 4.0 tumors per +/− mouse (n = 11); and 3.6 tumors per +/+ mouse (n = 8). In a second experiment of 17 weeks, mean tumor numbers were as follows: 1.6 tumors per −/− mouse (n = 10) and 3.0 tumors per +/− mouse (n = 11). No malignant tumors were found in 23 HIPK1−/− mice examined, although they did arise in WT and heterozygous mice (2/8 and 3/22, respectively) by 15 weeks. The vast majority of skin tumors were identified as papillomas, with the remainder diagnosed histologically as keratoacanthomas or squamous cell carcinomas (Table 1). These data indicate that HIPK1 is involved in (at least) malignant squamous cell tumor formation in vivo, and suggest that, like Mdm2, HIPK1 can promote oncogenesis.

Figure 7.

Skin tumor formation in mice treated with DMBA. The back skin of 8-week-old mice was shaved and painted with 10 μg of DMBA in 0.2 ml of acetone once a week for 14 weeks. Tumors in representative organs (including skin) were scored once a week. The proportions of tumors of various sizes at 14 weeks are shown in Inset. Mean tumor sizes were as follows: 3.1 mm (HIPK1−/− mice), 4.2 mm (+/−), and 4.1 mm (+/+). Similar results were obtained for a second experiment in which mice were treated with DMBA for 17 weeks.

Table 1.

Distribution of tumor types

| HIPK1 genotype | Total tumor no.* | Distribution of tumor types

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Papillomas | Keratoacanthomas | Squamous cell carcinomas | ||

| +/+ | 29 | 24 | 3 | 2 |

| +/− | 44 | 37 | 4 | 3 |

| −/− | 17 | 14 | 3 | 0 |

Tumors were scored once a week and histological type was determined in 8 HIPK1+/+, 22 HIPK1+/−, and 23 HIPK1−/− mice.

Discussion

How might HIPK1 modulate p53 function? In our in vivo assays, p53 underwent specific serine phosphorylation only when HIPK1 was present. Serine phosphorylation at specific residues has been shown to govern p53's ability to transactivate particular target genes (24, 25). HIPK1 may itself be phosphorylating p53, or HIPK1 binding to p53 may facilitate serine phosphorylation of p53 by another protein kinase. Another possibility is that the conformation of p53, and thus, its activity might be altered by the binding of HIPK1. Interaction of p53 with c-Abl (independent of its kinase activity) has been shown to induce a conformational change in p53 such that p53 tetramers are stabilized and DNA-binding activity is enhanced (26).

Kim et al. (11) have suggested that mouse HIPK1 may act as a transcriptional cofactor (repressor) interacting with the homeoproteins NKx-1.2 and NK-1. We have shown that human HIPK1 interacts with p53 through a domain that does not overlap with that which is involved in homeoprotein interaction. Several other proteins can interact with HIPK1 through its p53-binding domain (Y.L. and M.D., unpublished data), including Hic5 (27), UBC9 (28), and zyxin (29). Interactions with Hic5 and zyxin are particularly interesting because these proteins are recruited into focal adhesions and provide a link with the extracellular matrix (focal adhesion complex; refs. 29 and 30). Interestingly, HIPK1 is expressed at high levels in oncogenically transformed rat embryonic fibroblasts and MCF7 cells, whereas Hic5 levels are undetectable. Subsequent analyses of a large number of tumor and normal cell lines have shown that expression patterns of HIPK1 and Hic5 are negatively correlated (Y.L. and M.D., unpublished data). It is possible that, in untransformed cells, HIPK1 is retained in the cytoplasm through its interactions with focal adhesion proteins such as Hic5. Under conditions that promote transformation and reduce Hic5 levels, HIPK1 might be freed to transmigrate to the nucleus, interact with nuclear p53, and modulate p53-dependent function such that oncogenesis is enhanced.

That HIPK1 may be an oncogene was supported by our examination of HIPK1-deficient mice. Although HIPK1−/− mice were phenotypically normal, they were more resistant to the development of DMBA-induced skin tumors (particularly benign papillomas) than WT littermates. The loss of HIPK1 also had a protective effect with respect to malignant progression. Similarly, in colony-formation assays, HIPK1−/−-transformed MEF colonies grew more slowly than the equivalent HIPK1+/+ cells. Finally, HIPK1 was up-regulated in tumor cell lines. We speculate that these differences in malignant progression may result from differences in downstream events mediated by p53. Such differences and their relation to HIPK1 warrant future study.

Acknowledgments

We thank W. Boyle for help with the p53 phosphopeptide analysis, A. Sands for critical reading, our laboratory colleagues for technical support and helpful discussions, M. Saunders for scientific editing, I. Ng and D. Bouchard for administrative assistance, and M. Oren and J. Manfredi for providing plasmids containing the Mdm2 promoter and the p21 promoter, respectively.

Abbreviations

- HIPK1

homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 1

- MEF

mouse embryonic fibroblasts

- DMBA

7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene

- HA

hemagglutinin

References

- 1.Hollstein M, Sidransky D, Vogelstein B, Harris C C. Science. 1991;253:49–53. doi: 10.1126/science.1905840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levine A J. Cell. 1997;88:323–331. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giaccia A J, Kastan M B. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2973–2983. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.19.2973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prives C. Cell. 1998;95:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81774-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meek D W. Semin Cancer Biol. 1994;5:203–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haupt Y, Maya R, Kazaz A, Oren M. Nature. 1997;387:296–299. doi: 10.1038/387296a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Midgley C A, Lane D P. Oncogene. 1997;15:1179–1189. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Momand J, Zambetti G P, Olson D C, George D, Levine A J. Cell. 1992;69:1237–1245. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90644-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oliner J D, Kinzler K W, Meltzer P S, George D L, Vogelstein B. Nature. 1992;358:80–83. doi: 10.1038/358080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oliner J D, Pietenpol J A, Thiagalingam S, Gyuris J, Kinzler K W, Vogelstein B. Nature. 1993;362:857–860. doi: 10.1038/362857a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim Y H, Choi C Y, Lee S J, Conti M A, Kim Y. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25875–25879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ko L J, Prives C. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1054–1072. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.9.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bartel P L, Chien C T, Stenglanz R, Fields S. In: Cellular Interactions in Development: A Practical Approach. Hatley D A, editor. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press; 1993. pp. 153–179. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyle W J, van der Geer P, Hunter T. Methods Enzymol. 1991;201:110–140. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)01013-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barak Y, Juven T, Haffner R, Oren M. EMBO J. 1993;12:461–468. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05678.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Resnick-Silverman L, St. Clair S, Maurer M, Zhao K, Manfredi J J. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2102–2107. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.14.2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Souza G M, Lu S, Kuspa A. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1998;125:2291–2302. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.12.2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell E L, Santibanez-Koref M F. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1990;2:278–289. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870020405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meek D W, Eckhart W. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:461–465. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.1.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steegenga W, Shvarts A, Larr T V, van der Eb A J, Jochemsen A G. Oncogene. 1995;11:49–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCurrach M E, Connor T M, Knudson C M, Korsmeyer S J, Lowe S W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2345–2349. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corominas M, Leon J, Kamino H, Cruz-Alvarez M, Novick S C, Pellicer A. Oncogene. 1991;6:645–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quintanilla M, Brown K, Ramsden M, Balmain A. Nature. 1986;322:78–80. doi: 10.1038/322078a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dumaz N, Meek D W. EMBO J. 1999;18:7002–7010. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.24.7002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lohrum M, Scheidtmann K H. Oncogene. 1996;13:2527–2539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nie Y, Li H H, Bula C M, Liu X. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:741–748. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.3.741-748.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shibanuma M, Mashimo J, Kuroki T, Nose K. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:26767–26774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson E S, Blobel G. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26799–26802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.26799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Macalma T, Otte J, Hensler M E, Bockholt S M, Louis H A, Kalff-Suske M, Grzeschik K H, von der Ahe D, Beckerle M C. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31470–31478. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nishiya N, Iwabuchi Y, Shibanuma M, Cote J F, Tremblay M L, Nose K. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9847–9853. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]