Abstract

This study investigates the phenomenon of IS6110-mediated deletion polymorphism in the direct repeat (DR) region of the genome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clinical isolates and their putative predecessors were compared using a combination of DR region restriction fragment length polymorphism, IS6110 DNA fingerprinting, spoligotyping, and DNA sequencing, which allowed the mapping of chromosome structure and deletion junctions. The data suggest that adjacently situated IS6110 elements mediate genome deletion. However, in contrast to previous reports, deletions appear to be mediated by inversely oriented IS6110 elements. This suggests that these events may occur via mechanisms other than RecA-mediated homologous recombination. The results underscore the important role of IS6110-associated deletion hypervariability in driving M. tuberculosis genome evolution.

It has been suggested that insertion sequence-mediated deletion events are an important mechanism driving mycobacterial genome variation (6, 11). Homologous recombination between directly repeated IS6110 elements has been proposed as a likely mechanism for genomic deletions in clinical isolates (11). On insertion, the IS6110 element generates 3- or 4-bp duplications of the sequence immediately flanking the point of insertion (9), and the absence of these 3- or 4-bp direct repeats (DRs) is interpreted to reflect homologous recombination events between two IS6110 elements (6, 11). This knowledge was used in conjunction with in silico analysis of sequences flanking the 16 IS6110 elements in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv genome to identify the deletions RvD3, RvD4, and RvD5 (6). Similarly, analysis of sequences immediately flanking IS6110 elements in a 20-kb variable region of the chromosome provides further examples of the absence of flanking DRs, again implying IS6110-mediated deletion events (20). However, to our knowledge, no study has yet fully investigated evolutionary intermediates to substantiate this hypothesis.

Thus far, the phenotypic impact of the described deletions remains uncertain, with much speculation on the proposed function of deleted and disrupted genes (3, 6, 15, 26, 42). Intriguingly, increasing amounts of genomic deletion have been associated with a reduced likelihood for the strain to cause pulmonary cavitation (22). Also, it has been suggested that there is a correlation between the progressive accumulation of deletions and Mycobacterium bovis BCG attenuation (3). However, the genetic basis for these phenomena remains unclear.

To date, attention has focused mainly on comparisons of the Mycobacterium species for which the complete genome sequence is available, for example, M. tuberculosis, M. bovis, and M. leprae. Clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis have been relatively neglected by the field of comparative genomics. However, some investigators have examined deletion polymorphism in clinical isolates, specifically focusing on the DR region of the genome (13, 36). This locus consists of numerous copies of a 36-bp DR, separated by variable spacer sequences of 35 to 41 bp long (19). Each DR unit with its associated spacer is referred to as a direct variable repeat (DVR) (17). The DR region has been described as a hot spot for the insertion of an IS6110 element in members of the M. tuberculosis complex (19). It is speculated that this could reflect either true preferential insertion or reduced frequency of excision of the element once inserted into this region (19). Alternatively, this region may represent the ancestral IS6110 integration site in the M. tuberculosis chromosome, with the current chromosomal arrangement of the various copies of IS6110 reflecting outward migration from this region (9, 30).

The DR region exhibits polymorphism in M. tuberculosis, and this has been exploited for strain typing using a novel PCR-based fingerprinting method known as spoligotyping (16, 21), which is dependent on the presence or absence of variable spacer sequences between the DRs. The present understanding is that homologous recombination between adjacent or spatially distant DR elements is responsible for the observed variability (13, 17, 19, 36). In addition, mutational events mediated by IS6110 also contribute to diversification of this region. These events can include transposition and recombination leading to deletion (13, 17, 36).

This study investigates the DR region as a model locus to study the evolution of chromosomal domains where adjacent IS6110 elements are known to occur. We address the phenomenon of deletion polymorphism in the DR regions of clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis. Five discrete deletion polymorphisms in the DR region were investigated. Sequencing of the deletion junctions and comparison to putative predecessor strains (as defined by genotyping) have been utilized to elucidate the mechanisms leading to genome deletions. The results support the involvement of the insertion sequence IS6110 in the observed deletions. However, in contrast to previous reports, the data suggest that IS6110-mediated deletion occurs either via unidentified intermediate strains or by mechanisms other than homologous recombination between directly repeated copies of the element.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study setting and strain selection.

An ongoing molecular epidemiology study of tuberculosis in a high-incidence community in the Western Cape, South Africa, has produced a database of more than 2,000 M. tuberculosis isolates from over 800 patients (37, 38). These isolates have been typed according to internationally standardized protocols by IS6110 DNA fingerprinting (35) and DR region restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) (19). Five isolates (392, 397, 704, 780, and 973) (Fig. 1), representing examples of the three dominant strain family groupings within the study community (38) (where a family of strains is defined as isolates which are >65% related in terms of IS6110 DNA fingerprinting, as determined by GelCompar [Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium]) were selected for further analysis. These isolates were chosen on the basis of spoligotypes, which indicated a deletion of the 5′ portion of the DR region. An additional three isolates (Fig. 1) representing putative predecessors of strains 392, 397, and 704 (1985, 176, and 1227, respectively) were investigated to establish the mechanisms whereby the observed deletions occurred. The putative predecessors were identified by either (i) GelCompar comparisons of DNA fingerprints detected with oligonucleotide primers IS-3′, IS-5′, and DR (strains 1985 and 176) or (ii) phylogenetic analysis of a group of closely related strains (1227) (39).

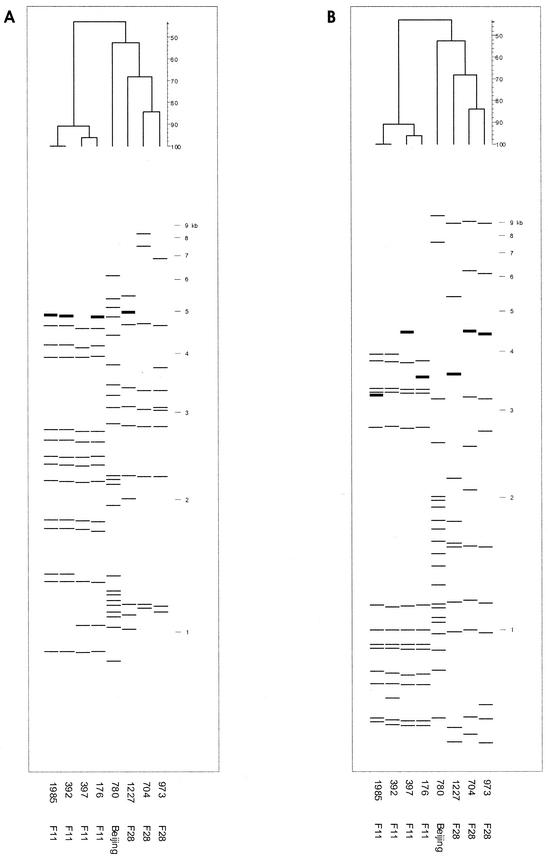

FIG. 1.

GelCompar representation of IS6110 DNA fingerprints of strains utilized for DR region investigation. (A) IS-3′ DNA fingerprints, (B) IS-5′ DNA fingerprints. PvuII fragments that cohybridize with DR bands (thick lines) are indicated. The molecular sizes (in kilobases) of DNA are given to the right of the DNA fingerprints. At the bottom of the figure, the isolate numbers are given first, followed by the strain families (41).

DNA hybridization.

Southern blots containing PvuII-digested genomic DNA were sequentially hybridized with enhanced-chemiluminescence-labeled IS-3′ (35) (Fig. 1A), IS-5′ (40) (Fig. 1B) and Marker X (Roche), as recommended by the manufacturer (Amersham). To identify DR-containing PvuII fragments, membranes were hybridized with 32P-labeled DRr probe (19), as previously described (39).

Spoligotyping.

DNA polymorphism in the DR locus was detected by spoligotyping according to a standardized protocol (21). Briefly, the method relies on the presence or absence of spacer sequences between the characteristic 35- to 41-bp DRs. The DRa (5′-biotinylated) and DRb oligonucleotides (Table 1), complementary to either side of the DR unit, were utilized to amplify the intervening spacer regions from clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis. The resulting amplification products were then hybridized to a commercially available membrane (Isogen Biosciences BV, Maadsen, The Netherlands), with covalently linked parallel rows of 43 synthetic oligonucleotides representing the unique spacer sequences between DR units in the DR region. This generated a characteristic spoligotype pattern for each isolate, where a positive hybridization signal was indicative of the presence of a particular spacer.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides utilized in this study

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Application |

|---|---|---|

| DRa | (5′ biotin)GGT TTT GGG TCT GAC GAC | Spoligotyping |

| DRb | CCG AGA GGG GAC GGA AAC | Spoligotyping |

| 16B7del | CCT TGC TGT CCC GCC AAT AC | Amplification of DR region and flanking sequence |

| 1919del | GCC GAA GTC ACG GCA GAC TG | Amplification of DR region and flanking sequence |

| 16B7delRb | TGC AGA AGA AGC TGG CGA AG | Sequencing of cloned regions |

| IS-5′ | GGT ACC TCC TCG ATG AAC CAC | Sequencing and PCR amplification from 5′ terminal of IS6110 |

| IS-3′ | TTC AAC CAT CGC CGC CTC TAC C | Sequencing and PCR amplification from 3′ terminal of IS6110 |

| 16B7delF41 | TGA TCG ACG CGA ACC TGT C | Sequencing of cloned regions |

| 16B7delfF47 | GCT GCG GAT GTG GTG CTG G | Sequencing of cloned regions |

| 16B7delF63 | TGA TAG AAG CCG GAA AGC TCC | Sequencing of cloned regions |

DNA manipulation.

PCR amplifications were performed with the Expand Long Range PCR system (Roche). Reaction mixtures contained 1 μg of DNA template, 50 pmol of each primer (see Fig. 3A and Table 1), 1× reaction buffer 3, and 5 U of enzyme. Cycling conditions included a 2-min 94°C denaturation step, followed by 35 cycles (with 1 cycle consisting of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at the specified annealing temperature, and the specified extension time at 68°C), followed by a 10-min extension step at 68°C (times and temperatures specified in Table 2). PCR products were electrophoretically fractionated in 0.8% agarose (1× Tris-borate-EDTA [pH 8.3]) and then visualized under UV after ethidium bromide staining. PCR products were purified with the Wizard PCR purification kit (Promega) and subsequently cloned using the pGEM-T Easy vector system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Plasmids were isolated using the Wizard DNA purification system (Promega), restriction mapped, and sequenced. All DNA sequencing reactions were performed on an ABI3100 automated sequencer.

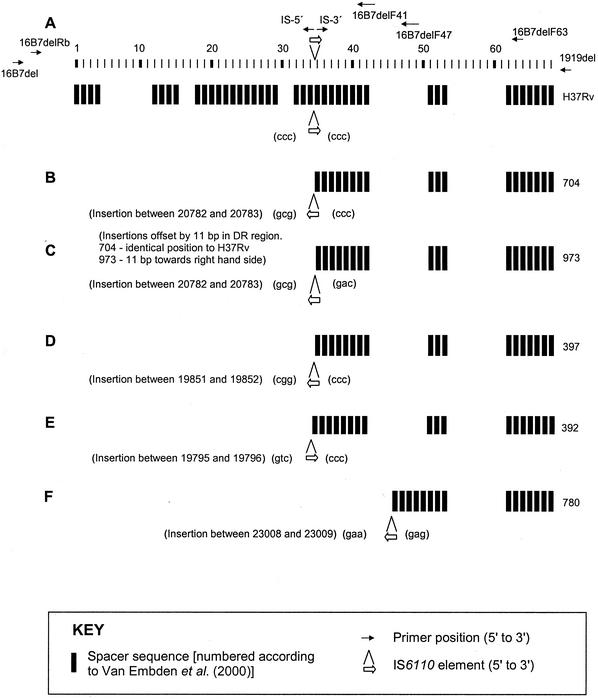

FIG. 3.

Arrangement of DVRs and IS6110 insertions in the DR regions of clinical isolates relative to those of M. tuberculosis H37Rv. The position and orientation of the IS6110 insertion, arrangement of DVRs and flanking 3-bp DRs (in brackets) are shown for M. tuberculosis H37Rv (A) and clinical isolates 704 (B), 973 (C), 397 (D), 392 (E), and 780 (F). The positions of oligonucleotides utilized in this study are shown relative to M. tuberculosis H37Rv (positions of DR-flanking sequence primers not to scale).

TABLE 2.

PCR products

| Isolate name | Primer pair | Product size (kb) | Annealing temp (°C) | Extension time (min) | GenBank accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H37Rv (cosmid MTCY16B7) | 16B7del/1919del | 9.8 | 65 | 12 | Z81331 |

| 1227 | 16B7del/IS-3′ | 3.0 | 62 | 6 | AF390041, AF390042 |

| IS-5′/IS-5′ | 3.6 | 62 | 6 | AF390043, AF390044 | |

| 1919del/IS-3′ | 1.6 | 62 | 6 | AF390045, AF390046 | |

| 704 | 16B7del/1919del | 5.5 | 65 | 12 | AF390047, AF390048, AF390049, AF390050 |

| 973 | 16B7del/1919del | 5.5 | 65 | 12 | AF390051, AF390052, AF390053, AF390054 |

| 176 | 16B7del/IS-3′ | 3.8 | 62 | 6 | AF390058, AF390059 |

| IS-5′/IS-5′ | 2.8 | 62 | 6 | AF390060, AF390061 | |

| 1919del/IS-3′ | 1.6 | 62 | 6 | AF390062, AF390063 | |

| 397 | 16B7del/IS-3′ | 3.4 | 62 | 10 | AF390064, AF390065 |

| 1919del/IS-5′ | 1.5 | 62 | 10 | AF390066, AF390067, AF390068 | |

| 1985 | 16B7del/IS-5′ | 6.0 | 62 | 6 | AF411182, AF411183 |

| 1919del/IS-3′ | 1.6 | 62 | 6 | AF390056, AF390057 | |

| 392 | 16B7del/IS-5′ | 3.6 | 62 | 10 | AF390069, AF390070 |

| 1919del/IS-3′ | 1.6 | 62 | 10 | AF390071 | |

| 780 | 16B7del/1919del | 3.2 | 65 | 12 | AF390039, AF390040 |

Sequence analysis.

The DNA sequence of the M. tuberculosis MTCY16B7 cosmid was downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The BLASTN algorithm was used to identify the positions of IS6110 insertions and to localize the deletion junctions. The precise points of insertion into the DR region were confirmed by comparison to the published MTCY16B7 sequence (7) and recently reported sequence data (2, 36). DVRs were numbered according to the numbering system of van Embden et al. (36). For comparative purposes, the original numbering of DVRs (21) and the rational nomenclature proposed by Dale et al. in 2001 (10) are also shown (Fig. 2 and Table 3, respectively).

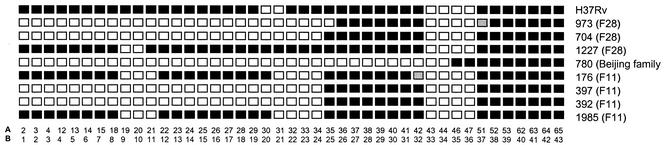

FIG. 2.

Spoligotype patterns of strains utilized for DR region investigation. Each row represents the spoligotype pattern of one isolate. Each square represents one DVR, numbered according to the numbering systems of van Embden et al. (36) (A) and Kamerbeek et al. (21) (B). Black squares indicate positively hybridizing DVRs. Shaded squares indicate DVR sequences not detected by spoligotyping but shown to be present by DNA sequencing. Isolate numbers are indicated with strain families in parentheses (41).

TABLE 3.

Rational nomenclature (binary, octal, and hexadecimal assignments)a

| Strain | System | Assignment |

|---|---|---|

| H37Rv | Binary | 1111111111111111111001111111111100001111111 |

| Octal | 777777477760771 | |

| Hexadecimal | 7F-7F-7C-7F-F0-7F | |

| 973 | Binary | 0000000000000000000000000111111100001111111 |

| Octal | 000000003760771 | |

| Hexadecimal | 00-00-00-07-F0-7F | |

| 704, 392, 397 | Binary | 0000000000000000000000001111111100001111111 |

| Octal | 000000007760771 | |

| Hexadecimal | 00-00-00-0F-F0-7F | |

| 1227 | Binary | 1111111100111111111111111111111100001111111 |

| Octal | 776377777760771 | |

| Hexadecimal | 7F-4F-7F-7F-F0-7F | |

| 780 | Binary | 0000000000000000000000000000000000111111111 |

| Octal | 000000000003771 | |

| Hexadecimal | 00-00-00-00-03-7F | |

| 176, 1985 | Binary | 1111111100011111111100001111111100001111111 |

| Octal | 776177607760771 | |

| Hexadecimal | 7F-47-7E-0F-F0-7F |

Spoligotype data shown in Fig. 2 are presented in the binary, octal, and hexadecimal formats recently proposed by Dale et al. (10) to facilitate interlaboratory spoligotype comparisons.

RESULTS

Spoligotype analysis of the DR region.

Spoligotyping and DR RFLP analysis identified strains from three dominant strain families with deletion of the 5′ portion of the DR region (strains 392, 397, 704, 973, and 780 [Fig. 2]). To investigate the mechanisms giving rise to the observed structure of the DR region in these strains, putative predecessor strains were identified. GelCompar analysis of IS-3′ and IS-5′ DNA fingerprints were utilized in conjunction with spoligotype data to identify strains most closely related to the strains with DR deletions but with an intact DR region (strains 176, 1985, and 1227 [Fig. 2]). Putative predecessor 176 and 1985 strains shared highly similar IS6110 banding patterns with strains 397 and 392, respectively. The differences between the banding patterns could be directly attributed to IS6110 insertions or deletions within the DR region. Although the IS6110 banding pattern of isolate 1227 differed slightly from that of isolates 704 and 973, the DR region reflected that the ancestral structure with an IS6110 insertion in the flanking region at position 3124718 (41) An ancestral strain for isolate 780 could not be identified.

The genotypically closely related strains 392 and 397 (as defined by IS-3′ and IS-5′ DNA fingerprinting) shared identical spoligotype patterns. This spoligotype pattern was also identical to that of the genotypically unrelated strain 704, which in turn differed from the genotypically closely related strain 973 by the presence of a hybridizing signal for one DVR (DR unit plus associated spacer). Strain 780 demonstrated a distinct spoligotype pattern, with deletion of the 5′ portion of the DR region.

Analysis of the structures of DR region and flanking chromosomal domains.

To determine the structure of the DR region and flanking chromosomal domains in the selected strains, these regions were amplified using the primer combinations shown in Table 2 and Fig. 3A, and subsequently cloned and sequenced. For reference purposes, sequence data are expressed relative to the M. tuberculosis H37Rv sequence (7), and DVRs (DRs plus associated spacer sequences) are numbered as recently proposed by van Embden et al. (36) (see Fig. 2 and Table 3 for alternative nomenclature according to the nomenclature system of Kamerbeek et al. [21]). Sequence encompassing the DVRs is referred to as the DR region, and sequence outside of this is referred to as DR-flanking sequence. Genetic maps were constructed on the basis of partial sequence data and were confirmed by comparison of predicted PvuII product sizes to the IS-3′, IS-5′, and DRr DNA fingerprints.

3′ DR structure.

Analysis of the presence or absence and arrangement of DVRs in strains 176, 392, 397, 704, 973, 1227, and 1985 demonstrated that these strains all had the same DVRs, and in the same order, as the 3′ side of the M. tuberculosis H37Rv DR region (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3A to E). However, in strain 973, the position of the IS6110 insertion was offset by 11 bp towards the 3′ side of the DR region, suggestive of an additional insertion event in this strain. A further difference between the strains was evident in the orientation of the respective IS6110 insertions, as illustrated in Fig. 3 and 4. The arrangement and sequence of DVRs in the DR region of strain 780 were identical to those in strains described by other investigators (2, 21, 36) and contains five unique DVRs not found in M. tuberculosis H37Rv (Fig. 3F). One of these unique DVRs contains a PvuII site (118 bp from IS6110) that results in a 579-bp PvuII fragment with only one complete DVR sequence which does not detectably hybridize to the DRr probe under the conditions employed. Therefore, the DR hybridizing band is not coincidental with any of the IS-3′ or IS-5′ hybridizing bands (Fig. 1)

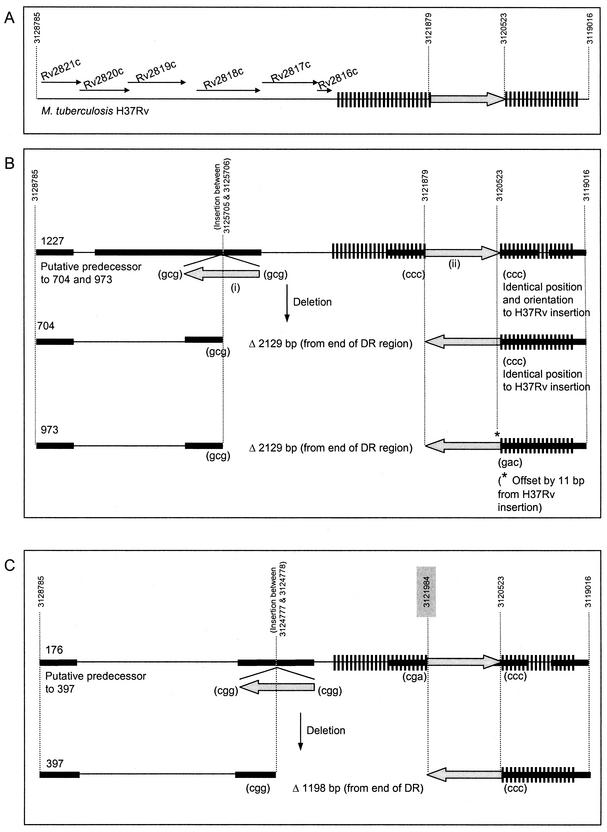

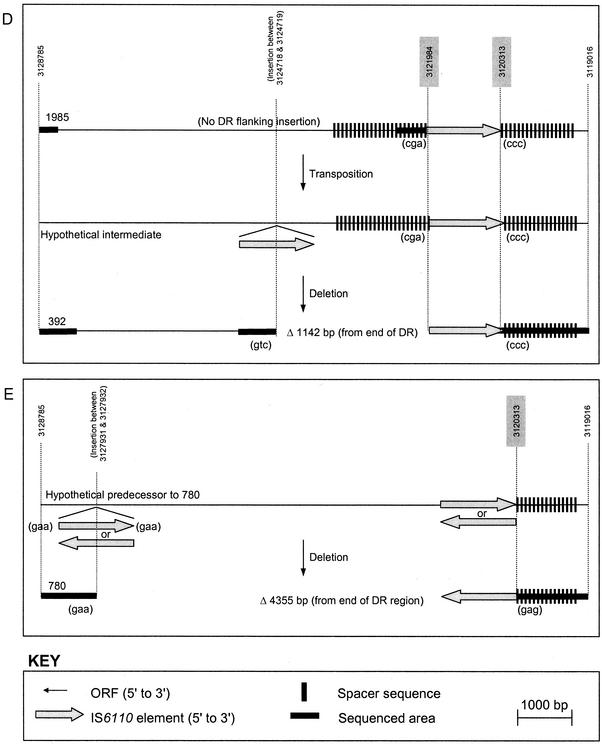

FIG. 4.

Deletion polymorphism in the DR region and flanking sequence of clinical isolates. Deletion polymorphisms in M. tuberculosis H37Rv and clinical isolates 176, 392, 397, 704, 780, 973, 1227, and 1985 are shown. (A) M. tuberculosis H37Rv; (B) putative predecessor 1227 and descendants 704 and 973; (C) putative predecessor 176 and descendant 397; (D) putative predecessor 1985, hypothetical intermediate, and descendant 392; (E) hypothetical predecessor and descendant 780. Three-base-pair duplications which arise due to transposition are indicated in brackets. The base pair positions relative to the M. tuberculosis H37Rv genome sequence are indicated by numbers above dotted lines. Estimates of base pair position for unique DR sequence not found in M. tuberculosis H37Rv are indicated by numbers on shaded background. Sequenced regions encompass 141 and 79 bp of the 3′ and 5′ ends of IS6110, respectively, and extend through the areas indicated by bold line. Note that the DR region insertions in strains 176 and 1985 lack 3-bp duplications, which is thought to indicate a prior IS6110-mediated deletion event.

5′ DR structures of strains 704 and 973 and putative predecessor strain 1227.

To investigate the possible deletion mechanism in strains 704 and 973, the sequences were compared to the sequence of putative predecessor strain 1227. Within the region of interest, strain 1227 has two IS6110 insertions labeled (i) and (ii) in Fig. 4B. One of these two IS6110 insertions, insertion (i), is in the DR-flanking region, while insertion (ii) is located within the DR region. Both of these insertions are flanked by unique 3-bp DRs which are characteristically formed during IS6110 transposition, although these differ between insertion (i) and insertion (ii).

Strain 704 has only one IS6110 insertion, which is in the same orientation as that of insertion (i). The 5′ sequence flanking this element is identical to that on the 5′ side of insertion (i), while the 3′-flanking sequence is identical to that flanking insertion (ii). The intervening sequence that is present in strain 1227 is absent in strain 704, and the single IS6110 insertion in strain 704 is not flanked by 3-bp DRs. Rather, the 3-bp sequences flanking the insertion in strain 704 correspond to the 3 bp 5′ of insertion (i) and the 3 bp 3′ of insertion (ii) in strain 1227. These data suggest that strain 704 arose from strain 1227 (or a similar closely related strain) via an IS6110-mediated deletion event. Elsewhere, IS6110-mediated deletion events have been suggested to occur via homologous recombination between directly repeated copies of the insertion sequence (11). In contrast, results presented here demonstrate that the ancestral strain has inversely orientated IS6110 elements in the DR region and DR-flanking region. This is suggestive of an alternative recombination mechanism or an unidentified intermediate strain.

The structure of strain 973 is very similar to that of strain 704, but strain 973 has an additional 11-bp deletion on the 3′ side of the single IS6110 insertion element (ii) in the DR region. We hypothesize that an additional IS6110 insertion occurred 11 bp 3′ of the ancestral insertion, into the same DVR, and that this was followed by subsequent recombination events leading to genome deletion. However, as the orientation of this insertion is unknown, it is not possible to elucidate whether recombination occurred between directly or inversely oriented IS6110 elements. This IS6110 insertion disrupts the spoligotyping primer DRb site in the DR unit flanking spacer 35, resulting in the absence of hybridization signal for DVR 35 (Fig. 2).

5′ DR structures of strains 397 and 392 and their respective putative predecessors, strains 176 and 1985.

To investigate the possible mechanisms giving rise to the observed structure of the DR region in strains 392 and 397, putative predecessor strains were examined (Fig. 4C and D). Using this approach, isolate 176, with a DR-flanking insertion in a position identical to that of isolate 397, but with an intact intervening sequence and DR region, was identified (Fig. 4C). Sequence data from the two strains show that the position and orientation of the DR region insertion in the predecessor strain are identical to those in M. tuberculosis H37Rv, with the DR-flanking region insertion in the opposite orientation. The overall structure of the DR region and flanking sequence in strain 176 is therefore very similar to that observed in strain 1227, the predecessor to strain 704 (compare Fig. 4B and C). These results suggest that the mechanism leading to deletion is similar to that proposed for strain 704.

A search of the complete DNA fingerprint database (>2,000 isolates) failed to identify an immediate predecessor strain for strain 392. The most closely related strain (according to IS6110 RFLP banding pattern [Fig. 1]) that was identified, namely, strain 1985, contained an identical (in terms of position and orientation) DR region insertion, but no DR-flanking region insertion. It is proposed that strain 392 evolved from strain 1985 (or a closely related strain) via an intermediate with an insertion between 19795 and 19796 bp (Fig. 4D), with a subsequent recombination event leading to deletion of one IS6110 element and the intervening sequence.

Interestingly, the absence of DVRs 31 to 34 on the spoligotype patterns of strains 176 and 1985 (Fig. 2), and the lack of 3-bp DRs flanking the insertion element suggests that these strains have undergone a prior IS6110-mediated deletion event in the DR region. It is hypothesized that an additional IS6110 insertion occurred 5′ of the ancestral insertion in a predecessor strain and that this mediated the subsequent deletion (not shown).

5′ DR structure of strain 780.

Strain 780 exhibits the largest deletion of sequence flanking the DR region (4,355 bp) in these isolates, and its structure is identical to that recently described by other investigators (2, 36). A database search failed to identify a predecessor strain; therefore, the relative orientations of IS6110 elements which may have mediated the deletion event are unknown.

DISCUSSION

Analyses of sequence data from M. tuberculosis clinical isolates (11, 20) and in silico sequence comparisons (6) have suggested that the insertion sequence IS6110 may promote chromosomal deletion events mediated by homologous recombination. The IS6110 element generates 3-bp duplications on insertion (9), and the absence of these short DRs flanking the IS6110 element has been cited as evidence of such events. However, to date, studies have not provided substantial evidence in the form of sequence data from predecessor strains. To address this question, this study investigates examples of deletion polymorphism in the DR regions of clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis. Strains were selected for investigation on the basis of DR RFLP and spoligotype data, which demonstrated the absence of the 5′ portion of the DR region. Where possible, putative predecessor strains were identified and analyzed to investigate mechanisms whereby deletion events occurred. Although these predecessor strains were not strictly isogenic, their IS6110 RFLP banding patterns suggested that they were closely related. This was supported by phylogenetic data which also predicted the evolutionary order (41). We believe that these strains reflect the ancestral structure of the DR region; however, we cannot exclude the possibility that unstable evolutionary intermediates occurred.

Analysis of the structures of the DR regions in strains 704 and 397 and comparison to their putative predecessor strains (1227 and 176, respectively) demonstrate that the putative predecessors both contain DR-flanking region insertions that are oriented opposite those in the DR region itself. This is in contrast to previous studies, which have suggested that putative predecessor strains have directly repeated IS6110 elements which undergo homologous recombination events leading to genome deletions (6, 11). In the present study, the sequence data suggest deletion of one insertion element and the intervening sequence from the predecessor on the basis of the absence of 3-bp repeats flanking the element. However, conventional understanding dictates that homologous recombination between directly repeated sequences results in deletion events, whereas homologous recombination between inverted repeats leads to inversion of the intervening sequence (23, 29, 31). While this study is not specifically designed to detect genome inversions, this phenomenon has not been previously reported in M. tuberculosis, including a study which compared the whole genome sequences of two independently sequenced isolates (14a).

Homologous recombination is often mediated by RecA and usually requires sequence homologies of 50 bp or more (25). Rarely, homologous recombination can occur between shorter regions of homology (>20 bp), and in such cases, it is often RecA independent (25). It is difficult to reconcile the inversely oriented IS6110 elements seen in this study with deletions by a classical homologous recombination pathway. It is also unlikely that the inverted repeats within the IS6110 elements act as sites promoting homologous recombination, as these are only 28 bp long. In addition, these internal inverted repeats are imperfect and demonstrate a 3-bp difference, and inspection of the sequence data does not reveal rearrangement of any of the inverted repeats, further supporting the conclusion that they do not function as substrates for homologous recombination in this instance.

The data do not, however, rule out homologous recombination via alternative scenarios. For example, there may exist an undetected intermediate strain in which one IS6110 copy is inverted by an undetermined mechanism, followed by homologous recombination between the now directly oriented IS6110 elements. Alternatively, a second IS6110 element may integrate into the DR region, immediately flanking, but oriented opposite the existing insertion, such that the existing triplet repeat is regenerated. The presence of an IS6110 element in the same orientation as the DR-flanking region insertion could then mediate deletion via a conventional homologous recombination pathway. If the DR locus is indeed a true preferential integration locus, then this is a plausible hypothesis. In this regard, it is interesting that sequence data suggest the occurrence of a second discrete insertion in isolate 973 within the same DVR (DVR 35). Furthermore, Groenen et al. (17) reported a second DR region insertion in a duplication of DVR 35, which might suggest that some inherent sequence characteristic promotes frequent insertion into this particular site.

An alternative mechanism is that of RecA-independent, spontaneous deletions mediated by short sequence homologies (1, 25). In this model, short sequence homologies of as little as 5 to 8 bp can mediate large deletions (700 to 1,000 bp) by a slipped mispairing mechanism. It is possible to apply this model to the strains investigated here, by considering the terminal part of the inverted repeats (excluding the 3-bp difference) as the substrate for this type of recombination event. Slipped mispairing between the two right-hand inverted repeats of the IS6110 elements could then lead to deletion of one element and the intervening sequence.

Other possible deletion mechanisms were discussed by Fang et al. (11) and included site-specific recombination and transpositionally mediated mechanisms. Site-specific recombination involves recombination between predetermined loci (18), but as with homologous recombination, site-specific recombination between inverse repeats will lead to inversion of the intervening sequence (28) and is therefore unlikely to be occurring here due to the observed deletion of the intervening sequence. The transpositionally mediated mechanisms include deletion of target DNA on insertion sequence (IS) integration, IS excision with associated deletion, and deletion of sequence flanking the donor IS copy on duplicative transposition (8). It is evident that numerous mechanisms can be invoked to explain the observed deletion events. While homologous recombination via an unidentified intermediate strain may be the simplest explanation, in the absence of confirmed immediate predecessor strains and knowledge of IS6110 transposition mechanisms, the mechanism remains unproven.

Interestingly, in strain 392, the position of the point of IS6110 integration into the DR region is identical to that of the closely related strain 397, but the orientation of the element is opposite that of strain 397. It is proposed that the opposing orientation of the remaining IS6110 element in these two strains is the result of two independent recombination events. This is supported by sequence analysis of the DR-flanking region, which revealed slightly offset IS6110 integration points in the two strains, indicative of discrete IS6110 transposition events. In the case of strain 392, deletion may be mediated by homologous recombination between directly repeated IS6110 elements. However, in the absence of a defined predecessor strain, this remains speculative.

Analysis of strain 780 revealed the largest deletion relative to M. tuberculosis H37Rv, identical to the deletion recently identified by van Embden et al. (36). In this case, the DR IS6110 insertion occurs in a newly identified DVR (2, 36) and is not identical to the M. tuberculosis H37Rv insertion. Without the support of data from predecessor strain types, it is difficult to speculate on the mechanism whereby this deletion occurred. Extensive analysis of the strain database did not reveal the presence of a putative ancestor, which may reflect that this deletion is a relatively ancient event. This is supported by the widespread distribution of this strain worldwide (5).

This study has identified a number of discrete IS6110 integration points within an 8-kb region encompassing part of the DR locus (n = 3) and its flanking sequence (n = 4) in the five strains analyzed. Intriguingly, we have identified a number of isolates which contain an IS6110 insertion at the so-called ancestral DR insertion site, but the orientation of the insertion is opposite that which is normally observed. Other investigators have reported three additional integration points within the DR region (4, 14, 17, 36). Therefore, the DR region and its flanking sequence represent a further example of a preferential insertion locus. The preferential integration of IS6110 apparently causes the region to be prone to IS6110-mediated deletion events, as deletions of DR-flanking sequence ranging in size from 1,142 to 4,355 bp were identified. A similar scenario was suggested for a 20-kb hypervariable region recently described by Ho et al. (20). Factors influencing the frequency of recombination events within a preferential integration site are as yet unknown, but it is expected that proximity and relative orientation of IS6110 elements, as well as the sequence of the surrounding chromosomal region, will play a role.

Further investigation will be necessary to establish whether deletion-associated hypervariability is a feature of other IS6110 preferential integration regions that have been identified (12, 24, 32, 33, 40). The results of preliminary analysis (not shown) demonstrate that the majority (11 of 12) of deletions identified in a previous study (40) correspond to preferential integration regions, as identified by mapping of IS6110 insertion sites to the M. tuberculosis H37Rv genome (32, 33, 40). Together, these findings support the role of IS6110 as a mediator of genome diversity in M. tuberculosis. In the absence of horizontal gene transfer (7) and with the limited sequence diversity (27, 34) that is observed in the pathogen, IS6110-mediated deletion may represent an important mechanism for strain adaptation.

Acknowledgments

Samantha L. Sampson was supported by the GlaxoSmithKline Action TB Initiative. We also thank the IAEA (projects SAF6/003 and CRP 9925) for financial assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albertini, A. M., M. Hofer, M. P. Calos, and J. H. Miller. 1982. On the formation of spontaneous deletions: the importance of short sequence homologies in the generation of large deletions. Cell 29:319-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beggs, M. L., K. D. Eisenach, and M. D. Cave. 2000. Mapping of IS6110 insertion sites in two epidemic strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2923-2928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Behr, M. A., M. A. Wilson, W. P. Gill, H. Salamon, G. K. Schoolnik, S. Rane, and P. M. Small. 1999. Comparative genomics of BCG vaccines by whole-genome DNA microarray. Science 284:1520-1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benjamin, W. H., K. H. Lok, R. Harris, N. Brook, L. Bond, D. Mulcahy, N. Robinson, V. Pruitt, D. P. Kirkpatrick, M. E. Kimerling, and N. E. Dunlap. 2001. Identification of a contaminating Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain with a transposition of an IS6110 element resulting in an altered spoligotype. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1092-1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bifani, P. J., B. Mathema, N. E. Kurepina, and B. N. Kreiswirth. 2002. Global dissemination of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis W-Beijing family strains. Trends Microbiol. 10:45-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brosch, R., W. J. Philipp, E. Stavropoulos, M. J. Colston, S. T. Cole, and S. V. Gordon. 1999. Genomic analysis reveals variation between Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv and the attenuated M. tuberculosis H37Ra strain. Infect. Immun. 67:5768-5774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cole, S. T., R. Brosch, J. Parkhill, T. Garnier, C. Churcher, D. Harris, S. V. Gordon, K. Eiglmeier, S. Gas, C. E. Barry III, F. Tekaia, K. Badcock, D. Basham, D. Brown, T. Chillingworth, R. Connor, R. Davies, K. Devlin, T. Feltwell, S. Gentles, N. Hamlin, S. Holroyd, T. Hornsby, K. Jagels, B. G. Barrell, et al. 1998. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393:537-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Craig, N. L. 2002. Transposition, p. 2339-2362. In F. C. Neidhardt et al. (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 9.Dale, J. W. 1995. Mobile genetic elements in mycobacteria. Eur. Respir. J. Suppl. 20:633s-648s. [PubMed]

- 10.Dale, J. W., D. Brittain, A. A. Cataldi, D. Cousins, J. T. Crawford, J. Driscoll, H. Heersma, T. Lillebaek, T. Quitugua, N. Rastogi, R. A. Skuce, C. Sola, D. van Soolingen, and V. Vincent. 2001. Spacer oligonucleotide typing of bacteria of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex: recommendations for standardised nomenclature. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 5:216-219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fang, Z., C. Doig, D. T. Kenna, N. Smittipat, P. Palittapongarnpim, B. Watt, and K. J. Forbes. 1999. IS6110-mediated deletions of wild-type chromosomes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Bacteriol. 181:1014-1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fang, Z., and K. J. Forbes. 1997. A Mycobacterium tuberculosis IS6110 preferential locus (ipl) for insertion into the genome. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:479-481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang, Z., N. Morrison, B. Watt, C. Doig, and K. J. Forbes. 1998. IS6110 transposition and evolutionary scenario of the direct repeat locus in a group of closely related Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains. J. Bacteriol. 180:2102-2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Filliol, I., C. Sola, and N. Rastogi. 2000. Detection of a previously unamplified spacer within the DR locus of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: epidemiological implications. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1231-1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14a.Fleischmann, R. D., D. Alland, J. A. Eisen, L. Carpenter, O. White, J. Peterson, R. DeBoy, R. Dodson, M. Gwinn, D. Haft, E. Hickey, J. F. Kolonay, W. C. Nelson, L. A. Umayam, M. Ermolaeva, S. L. Salzberg, A. Delcher, T. Utterback, J. Weidman, H. Khouri, J. Gill, A. Mikula, W. Bishai, J. W. Jacobs, Jr., J. C. Venter, and C. M. Fraser. 2002. Whole-genome comparison of Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical and laboratory strains. J. Bacteriol. 184:5479-5490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gordon, S. V., R. Brosch, A. Billault, T. Garnier, K. Eiglmeier, and S. T. Cole. 1999. Identification of variable regions in the genomes of tubercle bacilli using bacterial artificial chromosome arrays. Mol. Microbiol. 32:643-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goyal, M., N. A. Saunders, J. D. van Embden, D. B. Young, and R. J. Shaw. 1997. Differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates by spoligotyping and IS6110 restriction fragment length polymorphism. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:647-651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Groenen, P. M., A. E. Bunschoten, D. van Soolingen, and J. D. van Embden. 1993. Nature of DNA polymorphism in the direct repeat cluster of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: application for strain differentiation by a novel typing method. Mol. Microbiol. 10:1057-1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hallet, B., and D. J. Sherratt. 1997. Transposition and site-specific recombination: adapting DNA cut-and-paste mechanisms to a variety of genetic rearrangements. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 21:157-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hermans, P. W., D. van Soolingen, E. M. Bik, P. E. de Haas, J. W. Dale, and J. D. van Embden. 1991. Insertion element IS987 from Mycobacterium bovis BCG is located in a hot-spot integration region for insertion elements in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains. Infect. Immun. 59:2695-2705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho, T. B., B. D. Robertson, G. M. Taylor, R. J. Shaw, and D. B. Young. 2000. Comparison of Mycobacterium tuberculosis genomes reveals frequent deletions in a 20 kb variable region in clinical isolates. Yeast 17:272-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamerbeek, J., L. Schouls, A. Kolk, M. van Agterveld, D. van Soolingen, S. Kuijper, A. Bunschoten, H. Molhuizen, R. Shaw, M. Goyal, and J. Van Embden. 1997. Simultaneous detection and strain differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for diagnosis and epidemiology. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:907-914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kato-Maeda, M., J. T. Rhee, T. R. Gingeras, H. Salamon, J. Drenkow, N. Smittipat, and P. M. Small. 2001. Comparing genomes within the species Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Genome Res. 11:547-554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kleckner, N., K. Reichardt, and D. Botstein. 1979. Inversions and deletions of the Salmonella chromosome generated by the translocatable tetracycline resistance element Tn10. J. Mol. Biol. 127:89-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurepina, N. E., S. Sreevatsan, B. B. Plikaytis, P. J. Bifani, N. D. Connell, R. J. Donnelly, D. van Sooligen, J. M. Musser, and B. N. Kreiswirth. 1998. Characterization of the phylogenetic distribution and chromosomal insertion sites of five IS6110 elements in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: nonrandom integration in the dnaA-dnaN region. Tuber. Lung Dis. 79:31-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lloyd, R. G., and K. B. Low. 1996. Homologous recombination, p. 2236-2255. In F. C. Neidhardt et al. (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 26.Mahairas, G. G., P. J. Sabo, M. J. Hickey, D. C. Singh, and C. K. Stover. 1996. Molecular analysis of genetic differences between Mycobacterium bovis BCG and virulent M. bovis. J. Bacteriol. 178:1274-1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Musser, J. M., A. Amin, and S. Ramaswamy. 2000. Negligible genetic diversity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis host immune system protein targets: evidence of limited selective pressure. Genetics 155:7-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nash, H. A. 1996. Site-specific recombination: integration, excision, resolution and inversion of defined DNA segments, p. 2363-2376. In F. C. Neidhardt et al. (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 29.Petes, T. D., and C. W. Hill. 1988. Recombination between repeated genes in microorganisms. Annu. Rev. Genet. 22:147-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Philipp, W. J., S. Poulet, K. Eiglmeier, L. Pascopella, V. Balasubramanian, B. Heym, S. Bergh, B. R. Bloom, W. R. Jacobs, Jr., and S. T. Cole. 1996. An integrated map of the genome of the tubercle bacillus, Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv, and comparison with Mycobacterium leprae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:3132-3137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roth, J. R. 1996. Rearrangements of the bacterial chromosome formation and applications, p. 2256-2276. In F. C. Neidhardt et al. (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 32.Sampson, S., R. Warren, M. Richardson, G. van der Spuy, and P. van Helden. 2001. IS6110 insertions in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: predominantly into coding regions. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3423-3424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sampson, S. L., R. M. Warren, M. Richardson, G. D. van der Spuy, and P. D. van Helden. 1999. Disruption of coding regions by IS6110 insertion in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuber. Lung Dis. 79:349-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sreevatsan, S., X. Pan, K. E. Stockbauer, N. D. Connell, B. N. Kreiswirth, T. S. Whittam, and J. M. Musser. 1997. Restricted structural gene polymorphism in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex indicates evolutionarily recent global dissemination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:9869-9874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Embden, J. D., M. D. Cave, J. T. Crawford, J. W. Dale, K. D. Eisenach, B. Gicquel, P. Hermans, C. Martin, R. McAdam, and T. M. Shinnick. 1993. Strain identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by DNA fingerprinting: recommendations for a standardized methodology. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:406-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Embden, J. D., T. van Gorkom, K. Kremer, R. Jansen, B. A. Der Zeijst, and L. M. Schouls. 2000. Genetic variation and evolutionary origin of the direct repeat locus of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 182:2393-2401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Warren, R., J. Hauman, N. Beyers, M. Richardson, H. S. Schaaf, P. Donald, and P. van Helden. 1996. Unexpectedly high strain diversity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a high-incidence community. S. Afr. Med. J. 86:45-49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Warren, R., M. Richardson, G. van der Spuy, T. Victor, S. Sampson, N. Beyers, and P. van Helden. 1999. DNA fingerprinting and molecular epidemiology of tuberculosis: use and interpretation in an epidemic setting. Electrophoresis 20:1807-1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Warren, R. M., M. Richardson, S. L. Sampson, G. D. van der Spuy, W. Bourn, J. H. Hauman, H. Heersma, W. Hide, N. Beyers, and P. D. van Helden. 2001. Molecular evolution of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: phylogenetic reconstruction of clonal expansion. Tuberculosis (Edinburgh) 81:291-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Warren, R. M., S. L. Sampson, M. Richardson, G. D. van der Spuy, C. J. Lombard, T. C. Victor, and P. D. van Helden. 2000. Mapping of IS6110. flanking regions in clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis demonstrates genome plasticity. Mol. Microbiol. 37:1405-1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Warren, R. M., E. M. Streicher, S. L. Sampson, G. D. van der Spuy, M. Richardson, D. Nguyen, M. A. Behr, T. C. Victor, and P. D. van Helden. 2002. Microevolution of the direct repeat region of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: implications for interpretation of spoligotyping data. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:4457-4465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zumarraga, M., F. Bigi, A. Alito, M. I. Romano, and A. Cataldi. 1999. A 12.7 kb fragment of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome is not present in Mycobacterium bovis. Microbiology 145:893-897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]