The δ-endotoxins are a superfamily of proteins that occur as crystalline inclusions in the spore-forming bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis (35). These toxins are of considerable interest as environmentally safe insecticides. Historically, B. thuringiensis toxins have been divided into two groups on the basis of target specificity: the insect-specific Cry (for crystal) proteins and the generally cytolytic Cyt proteins. It is mostly the Cry proteins that have been used in commercial insecticide preparations, and, naturally, there is a large body of literature about them (see reference 35 and references cited therein).

A distinct subgroup of the B. thuringiensis toxin superfamily comprises the proteins produced by Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis (B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis) and a few other subspecies. In contrast with Cry proteins, which are mostly specific against the orders Lepidoptera and Coleoptera, the Cyt proteins are toxic in vivo to the larvae of members of the order Diptera, such as mosquitoes and black flies. They show no amino acid sequence homology to the members of the Cry family of δ-endotoxins. Arguably the most studied of the polypeptides found in parasporal crystals of B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis is the 27-kDa protein Cyt1Aa1, previously known as CytA (44) and denoted here more generically Cyt1A, which serves in this article as a representative of the whole family of Cyt proteins. Although the activity spectrum of Cyt1A in vivo is restricted, in vitro it exhibits broad cytolytic activity against a variety of insect and mammalian cells, including erythrocytes, lymphocytes, and fibroblasts (25, 42). Studies using multilamellar liposomes (10, 22) and planar lipid bilayers (24) have demonstrated that the cytolytic action of Cyt1A is mediated by the toxin-lipid interaction. This is in clear contrast with the receptor-mediated insecticidal action of the genus-specific Cry proteins. While it has been hypothesized that Cyt1A acts via formation of transmembrane ionic channels and/or pores (24), the molecular mechanisms of the toxin-membrane interaction remain largely unknown.

BACILLUS THURINGIENSIS SUBSP. ISRAELENSIS AS A PESTICIDE

The toxicity of B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis parasporal bodies is due to a combination of four proteins: Cyt1A (27 kDa), Cry4A (128 kDa), Cry4B (134 kDa), and Cry11A (72 kDa) (23). It is not trivial to ascertain the contributions of individual toxins to the overall effect of B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis. The reasons include potential inactivation (or, conceivably, accidental activation by protease impurities) during chromatographic purification procedures, the immense complexity and variability of the in vivo assays (the use of different insect species at different developmental stages, different conditions of rearing the insects, and/or different feeding conditions—temperature, pH, and salinity), and different formulations of B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis (intact spores, solubilized crystals, reprecipitated crystals, and/or encapsulated spores or crystals). In fact, conflicting conclusions about the participation of Cyt1A in mosquitocidal activity in vivo have been reached. Delecluse et al. (8) disrupted the cyt1A gene in B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis, but this did not change the activity of this bacterium against three species of mosquito. On the other hand, Wu et al. (47), adopting the opposite strategy, expressed several combinations of B. thuringiensis toxin genes in the acrystalliferous B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis strain 4Q7. Their conclusion was that the simultaneous presence of Cyt1A and Cry11A results in toxicity four to five times higher than that of either protein alone. There is a growing consensus, supported by data, about synergism between Cyt1A and Cry11A (5, 35, 47) and about Cyt1A aiding in overcoming the insect's resistance to the Cry toxins (46). Thus, irrespective of the individual role of Cyt1A in mosquitocidal activity, it is important to acknowledge its potential in synergistic mixtures of B. thuringiensis preparations and in fighting insects' resistance to B. thuringiensis toxins. The B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis-based commercial products have proven efficient, cost-effective, and easy to formulate and to store (16). The two leading products in the United States are VectoBac and Tecknar, marketed respectively by Valent BioSciences and Certis.

STRUCTURE OF CYT1A

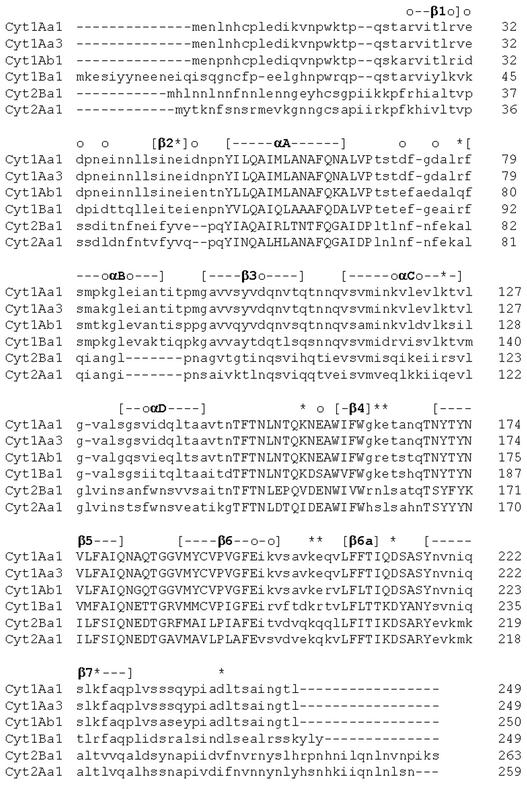

The first attempt to model the three-dimensional structure of Cyt1A was described in a 1988 publication (45). Due to the lack of experimentally determined structure of any homologous protein at that time, the authors could only rely on early, inefficient computer algorithms. Their model captured a few features of the structure, such as abundance of β-strands and two antiparallel α-helix bundles, but could not provide a description of the three-dimensional arrangement of the secondary structural elements. Prediction of the Cyt1A structure became possible only after Li et al. (28) determined the X-ray structure of the related B. thuringiensis toxin Cyt2Aa1 (in the absence of lipid). Similar to Cyt2Aa1, Cyt1Aa1 appears to consist of two outer α-helix hairpins (helices A-B and C-D) flanking a core of mixed β-sheet (strands 1 to 7) (Fig. 1). When amino acid sequences of six Cyt proteins from different subspecies of B. thuringiensis are aligned (Fig. 2), four blocks with high similarity scores and high statistical significance are found. Comparison of Fig. 1 and 2 indicates that the blocks (i.e., highly similar regions in all the Cyt proteins analyzed) are (i) helix A (consensus sequence YILQAIQLANAFQGALDP), (ii) the loop after helix D plus strand 4 (TFTNLNTQKDEAWIFW), (iii) strands 5 and 6 (TNYYYNVLFAIQNEDTGGVMACVPIGFE), and (iv) strand 6a and the following loop (LFFTIKDSARY).

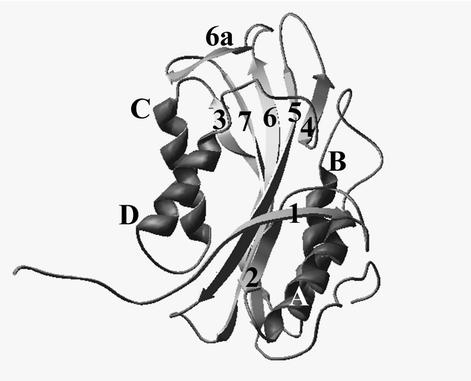

FIG. 1.

Predicted structure of Cyt1Aa1. The model, based on the X-ray crystallographic structure of Cyt2Aa1 (28), was created using the Swiss-PdbViewer 3.1 software (http://www.expasy.ch/spdbv/mainpage.htm). α-Helices are marked by letters, and β-strands are numbered.

FIG. 2.

Alignment of the amino acids of six Cyt proteins from different subspecies of B. thuringiensis: Cyt1Aa1 (CYTA_BACTI) from B. thuringiensis var. israelensis (44), Cyt1Aa3 (CYTA_BACTM) from B. thuringiensis var. morrisoni (12), Cyt1Ab1 (CYTA_BACTV) from B. thuringiensis var. medellin (41), Cyt1Ba1 (CYTA_BACTW) from B. thuringiensis var. neoleoensis (30), Cyt2Ba1 (CYTB_BACTI) from B. thuringiensis var. israelensis (21), and Cyt2Aa1 (CYTB_BACTY) from B. thuringiensis var. kyushuensis (27). Highly conserved blocks are in capital letters. Secondary-structure elements are marked above the sequences by Greek letters. Mutations (45) that affect toxicity and lipid binding are marked with asterisks, while those with no effect are marked with circles. The alignment was performed with the software MACAW 2.0.5, developed at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (Bethesda, Md.).

Ward et al. (45) performed systematic mutagenesis of Cyt1Aa1. Of 11 dysfunctional mutations (marked by asterisk in Fig. 2), 7 were found in the loops in the top half of the molecule as seen in Fig. 1, while only 5 of 17 benign mutations were found in that region of the molecule. This suggests that the most important part of the protein, responsible for toxicity and lipid binding, comprises the loops at the top of the molecule (as oriented in Fig. 1). Ward et al. mutated only charged residues, which are usually exposed on the surface of proteins. While bearing in mind that there are no data on the possible effect of the mutations on the structural stability of the toxin itself, one may tentatively assume that the mutated residues are important for electrostatic interactions with polar head groups of lipids. With more new mutants, it might be possible to probe the role of selected hydrophobic residues. Alternatively, cysteine residues inserted at judiciously selected locations might allow for disulfide clamping of Cyt1A, which may render whole regions of the toxin dimer surface unavailable for interaction with membranes. The latter approach would be especially informative in terms of pinpointing the regions responsible for lipid binding.

LIPID-INDUCED INHIBITION OF TOXICITY

After their initial observation that dissolved B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis toxins caused rapid cytolysis and hemolysis (42), Thomas and Ellar further showed that the toxin preparation lost its activity upon incubation with lipids (43). These authors demonstrated that the determinants important for toxin binding were the nature of the lipid polar head group (phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine, and sphingomyelin bound the toxin) and the presence of unsaturated fatty acyl chains. Haider and Ellar (22) found that the addition of B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis toxin to a suspension of multilamellar vesicles caused an immediate increase in turbidity which was ascribed to “the reorganization of lipid assemblies which include vesicularization and aggregation and/or fusion.” This conclusion could be corroborated and strengthened by performing experiments with better-defined unilamellar vesicles and using a more powerful technique, e.g., dynamic light scattering. In fact, visualization or sizing of lipid assemblies or lipid-toxin complexes after the lytic action of Cyt1A might be the crucial contribution to determining the toxin's mode of action, as discussed in more detail below.

CATION-SELECTIVE CHANNELS, TOXIN SEGMENTS, AND THE PORE MODEL

Knowles et al. (24) reported that Cyt1A formed cation-selective channels in planar lipid bilayers, but only at an elevated pH (9.5). Unfortunately, these authors did not record single-channel conductance but had to rely on multiple-channel recordings. Consequently, discrete conductance levels are not easily discernible from their data. Moreover, determining whether discrete conductance steps are due to formation of channels or to a much less specific perturbation of bilayer structure mediated by proteins is not always straightforward. A more thorough analysis of single-channel recordings of Cyt2Aa1, a toxin from B. thuringiensis var. kyushuensis, has been provided by the same group in a later paper (26). This work proved unequivocally that potassium channels are observed for at least 10 min after incorporation of the activated toxin into planar lipid bilayers. These authors also observed that upon incorporation into liposomes with entrapped glucose, the toxin caused glucose release. This raises the interesting question of whether glucose passes through a cation-selective channel or the toxin forms different kinds of openings in membranes of different radii of curvature.

All of the papers mentioned so far (22, 24, 26, 42, 43) have been cited in support of the colloid-osmotic lysis mechanism of Cyt1A-mediated cell damage (25). According to this hypothesis, Cyt1A forms cation-selective channels in the cell membrane; equilibration of cation concentrations across the membrane results in osmotic movement of water with subsequent swelling and eventual rupture of the cell. In the absence of direct physical evidence for a proteinaceous channel or pore, several research groups investigated the interaction between Cyt1A and lipids with the aim of identifying the protein regions that embed in the lipid bilayer. Szabo et al. (40) hypothesized that the segment comprising amino acids 116 to 126 forms an amphiphilic α-helix. They synthesized the peptide and determined that it was hemolytic. Gazit and Shai (19) fluorescently labeled two putative hydrophobic segments (amino acids 110 to 131 and amino acids 50 to 71) and used them in lipid binding assays. Both peptides bound strongly to zwitterionic lipids, self-associated, and interacted with each other; the segment consisting of amino acids 110 to 131 permeabilized lipid vesicles. Do these two studies constitute the proof that Cyt1A inserts in the membrane and forms proteinaceous channels or pores? The structural predictions of Szabo et al. (40) and Gazit and Shai (19) are validated by the current model of Cyt1Aa1 (Fig. 1 and 2). However, a synthetic-peptide approach to studying mechanisms of protein-lipid interactions may not always be the best: the behavior of helical peptides may be quite different when they are in isolation and when they engage in intramolecular interactions with surrounding amino acids within proteins. For example, circular dichroism spectra of the synthetic segment comprising amino acids 116 to126 showed that this peptide is helical in trifluoroethanol but not in water (40). Furthermore, extrinsic fluorescence labeling may alter physicochemical properties of the peptides, most notably their partitioning in the membrane. Gazit and Shai (19) reported that the probe with N-terminal fluorescence probe was localized in the hydrophobic interior of the bilayer. This fact by itself rules out the possibility that the helical peptides span the membrane: if that were the case, both the N and C termini would have to be on the opposite surfaces of the membrane and, thus, in a polar environment. Finally, the four α-helices of Cyt1Aa1, containing from 11 to 15 amino acids, are too short to span the membrane. Part of this criticism has already been formulated (4). In 1996, Li et al. (28) implicated the β-sheet, rather than the α-helices, in membrane binding, insertion, and pore formation. The strands in the β-sheet are, indeed, long enough to span the bilayer. Promdonkoy et al. (33) labeled three of the β-strands with the polarity-sensitive probe acrylodan and demonstrated that the strands face the nonpolar environment. The strands also appear to be protected from attack by water-soluble proteases, which suggests that they may span the bilayer rather than lie parallel to its surface. A comprehensive synthesis of the original seminal observations from the 1980s (29, 43, 45) and newer data (11, 28, 33) with preliminary results obtained by novel techniques such as acoustic waveguide spectroscopy and atomic force microscopy was recently presented by Ellar (13). A working model of the putative Cyt pore consists of six toxin molecules assembled like an open umbrella. The handle of the umbrella, comprising β-strands 5 to 7, spans the lipid membrane, while the top of the umbrella, made up of the α-helices, is splayed on the membrane surface (32; B. Promdonkoy and D. J. Ellar, unpublished data).

CHALLENGES TO THE PORE MODEL

By definition, transmembrane pores or channels must contain at least one part of the molecule that reaches across the lipid bilayer to the other side of the membrane. It is noteworthy that Du et al. (11) failed to observe any proteolysis of Cyt1A that was applied from outside the vesicle by proteases entrapped inside the vesicle. The most obvious explanation of this negative result would be that no part of the toxin penetrates the interior surface of the membrane.

A previous fluorescence spectroscopy study (4) probed the localization of the tryptophan region (strand 4 and the flanking areas) with respect to the membrane surface. The observed lack of a blue shift, lack of quenching by lipidic quenchers, and decreased quantum yield in the presence of lipid all suggested that the region of Cyt1A where the two tryptophans are located is not inserted in the lipid bilayer. However, this does not clearly challenge the pore hypothesis since these experiments did not address the localization of other parts of the protein, which were invisible to the spectrofluorometer. In fact, the current pore model localizes β-strand 4 to the membrane surface (32; Promdonkoy and Ellar, unpublished).

Several other data do question the notion of well-defined protein-lined pores formed by Cyt1A. First, the Cyt1A-induced leakage from vesicles exhibited kinetics independent of the size of the leaking molecule, between 0.6 and 10 kDa (3). This would be unlikely if the diameter of the pore were well defined as 1 or 2 nm (25). Second, the kinetics of the amide II proton/deuteron exchange upon hydration of lyophilized Cyt1A in D2O was not slowed by the presence of lipid; rather, the opposite was observed (4). This indicates that when the toxin is bound to lipid, all the amide protons are easily accessible to the aqueous solvent, suggesting that no significant part of Cyt1A inserts in the lipid bilayer core. Cyt1A is mostly (or perhaps completely) splayed out on the membrane surface. This hypothesis is consistent with another recent finding of Du et al. (11), namely, that upon membrane binding, Cyt1A exhibits new proteolytic sites for proteases applied from the same side as the toxin. (Of course, these results are also consistent with the umbrella-like pore model.) Additional biophysical data (4) lend further support to this hypothesis: (i) analysis of the shape and position of the amide I peak in the Cyt1A infrared spectra revealed that binding to the membrane causes a significant change in the Cyt1A structure, similar to thermal unfolding; (ii) differential scanning calorimetry confirmed that in the presence of lipid, Cyt1A did not undergo any detectable cooperative thermal transition; and (iii) at the same time, circular dichroism spectra showed no significant difference in secondary structure of Cyt1A upon membrane binding. Thus, it is only the tertiary structure that is loosened upon lipid binding; the bulk of the secondary structure is retained, perhaps in a form similar to the so-called molten-globule state (34). The only question pertaining to these experiments is whether the sensitivity of the employed biophysical methods is sufficient to detect a few amides (out of the 248 peptide bonds in Cyt1A) that might be buried in the membrane.

AGGREGATION

Aggregation of Cyt1A in the membrane appears to play an important role in the pore hypothesis. When a transmembrane pore is formed, often several molecules of toxin assemble to create the lining of the pore, as is the case with, e.g., the anthrax toxin (14). From a concentration-dependent lag of the toxin effect on the Malpighian tubules of insects (29) and from the analysis of Cyt1A-mediated release of a fluorescent dye from large unilamellar lipid vesicles (3), it was concluded that the membrane is affected only after it has harbored a sufficiently large number of Cyt1A molecules. Gazit et al. (18) showed that Cyt1A molecules can interact with each other via helices A and C on adjacent protein molecules. Nevertheless, there is only one published report of direct physical isolation, by sucrose density gradient centrifugation, of Cyt1A aggregates: Chow et al. (7) studied binding of 125I-labeled Cyt1A to red blood cells and cells of Aedes albopictus and Choristoneura fumiferana. One drawback of this study is the uncertain composition of the aggregates due to the use of whole cells, whose membranes contain endogenous proteins. Cyt1A might be complexed with those proteins rather than with itself. This caveat notwithstanding, there is now little disagreement on the notion that several (and perhaps many) molecules of Cyt1A must come into contact in the membrane for cytolysis to occur. As the channels or pores are usually formed by assembling a small number of protein subunits with a more or less constant stoichiometry, the pore hypothesis would be supported by finding only small oligomers. If, on the other hand, no aggregates, or only large aggregates, are found, an alternative hypothesis must be considered. This issue was directly addressed by Promdonkoy and Ellar (32; Promdonkoy and Ellar, unpublished). In the presence of the membrane, Cyt2A exhibited a laddering pattern in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis when the samples were not boiled before electrophoresis. However, the ladder did not show a molecular size limit or the maximum staining intensity in the region of 120 to 140 kDa, which would be expected for hexameric stoichiometry. Aggregates so large that they could not enter the gel were apparent in some, but not all, blots. The authors unsuccessfully attempted to electrophorese pore complexes stabilized by glutaraldehyde cross-linking. Perhaps a more specific distance-sensitive protein cross-linker that will covalently link only closely opposed proteins in the membrane of a lipid vesicle could be used to form stable higher-molecular-weight aggregates of the toxin, which could then be unequivocally resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Experiments with the light-activated cross-linker ruthenium(II) tris-bipyridyl dication (15) are under way in our laboratory.

DRIVING FORCE FOR MEMBRANE INTERACTION

What makes Cyt1A, a fairly soluble protein, interact with lipid in the first place? To dissolve B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis crystals, a high pH is required. Cyt1A can be precipitated from solution by lowering the pH to 4.5 (6). It was found that another B. thuringiensis toxin, Cry1C, showed a drastically increased surface hydrophobicity at that pH, paralleled by enhanced binding to lipids (2). Surface hydrophobicity of Cyt1A has not been measured, but many unrelated proteins, e.g., prion protein PrP (39) and a virus envelope protein (20), exhibit the same changes as Cry1C. The pH-induced destabilization of the tertiary structure of proteins, which simply open up and expose their hydrophobic interiors, seems to be a general phenomenon (17).

Table 1 summarizes data on the rate of Cyt1A-induced release of the fluorescent dye calcein from lipid vesicles and the apparent association constant (Kapp) of Cyt1A binding to lipid at three different pH values (3, 4). Clearly, lowering the pH increased the toxin efficiency. It is thus reasonable to expect that Cyt1A shares the mechanism of pH-induced increase in surface hydrophobicity and membrane binding with other proteins. At first glance, the described mechanism does not seem relevant for the insecticidal B. thuringiensis toxins since it is known that the pH in the midgut of insect larvae is alkaline (9). However, the pH in the gastrointestinal tract may differ considerably among species (38), and presumably there exists a longitudinal pH gradient within a larval gut. Furthermore, cell membranes are normally charged: most natural lipids are either zwitterionic or bear a net negative charge. Consequently, due to the Boltzmann distribution factor, the hydrogen ion concentration (and its negative logarithm, which is pH) close to the membrane surface is usually different from that in the cell bulk. Depending on the charge density and the salt and buffer concentrations, the surface pH may be 1 pH unit or more lower than the bulk pH (31). Due to the lack of current and relevant data (such as radial and longitudinal maps of pH gradients in the larval gut, obtained by techniques other than the bulk measurements with pH electrodes), at present we can only speculate. It is possible that when Cyt1A, solubilized by the alkaline pH in the larval gut, diffuses close to a cell membrane, the lower local pH induces a conformation change in the protein, making it more hydrophobic and, thus, more likely to bind to the membrane. Additional alternative mechanisms might be operative in cells (as opposed to lipid vesicles): before binding to lipid, Cyt1A may first interact with a membrane protein, which may induce a change to the membrane-active conformation of the toxin or solubilized Cyt1A may be—quite passively on its part—endocytosed by a gut cell and encounter the acidic interior of some cell compartments, including endocytotic vesicles themselves, which would switch Cyt1A into a membrane-active form. Such a mechanism has been well documented for many toxins (14). Whether the endocytotic pathway participates in the toxicity of Cyt1A to cells in vivo is uncertain. The above-described mechanisms might be deemed speculative, but they are presently the most adequate at hand to reconcile the in vitro data on enhanced activity at low pH with the in vivo data on toxicity at the neutral value of the bulk pH. While pH certainly plays a role in Cyt1A dissolution and activation, its role in membrane interaction itself is presently difficult to assess. In particular, the proposed pH-induced membrane affinity cannot explain the difference in Cyt1A toxicities to susceptible and nonsusceptible insect species whose midgut lumens have the same pH profile.

TABLE 1.

Rate (k) of Cyt1A-induced release of calcein from large unilamellar lipid vesicles (LUV) and the apparent association constant (Kapp) of binding of the Cyt1A protoxin to small unilamellar vesicles as a function of pHa

| pH | k (min−1) | Kapp (M−1) |

|---|---|---|

| 10.0 | 0.39 | 3,250 |

| 7.4 | 0.86 | 3,500 |

| 4.0 | 1.10 | 11,000 |

The three buffers used were 100 mM NaCl and 10 mM HEPES, 50 mM CAPS, or 50 mM citrate for pHs 7.4, 10, and 4, respectively. The calcein release experiments were carried out with 49 nM protoxin and 1.2 μM lipid. The binding data were obtained by titration of the protoxin fluorescence (1.7 μM protein) with lipid (0 to 2 mM).

Although pH is a factor in membrane binding of Cyt toxins, the interaction is not purely electrostatic since the membrane-bound toxin cannot be resolubilized by high salt or by changing pH (32; Promdonkoy and Ellar, unpublished). Clearly, van der Waals and hydrophobic forces must be involved in this binding.

CYT1A: A PORE FORMER OR A DETERGENT?

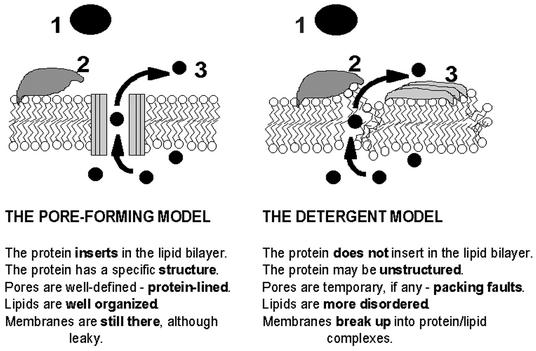

The data presented above, especially those in the section on challenges to the pore model, do not favor the pore-forming mechanism. The question is if Cyt1A does not form pores, how does it work? One possibility is that the Cyt1A aggregates adsorbed on the membrane surface cause large nonspecific defects in lipid packing through which intracellular molecules can leak—a mechanism similar to the so-called carpet model formulated for antimicrobial peptides by Shai (37). The aggregates may even completely destroy the membrane in a detergent-like manner, resulting in the complete absence of a vesicle (empty or otherwise). Most of the experimental evidence challenging the pore model (see the section on challenges to the pore model) would be consistent with such a detergent model. Additional support is provided by the observation that Cyt1A operates by an all-or-nothing mechanism—i.e., cells or vesicles are either intact or fully depleted of their contents; no vesicles that had only partially lost their contents were found (3). Importantly, the detergent-like action requires neither stoichiometric toxin assemblies nor stable penetration of the toxin across the lipid bilayer. One can easily envisage experimental tests of the model. First, very large molecules (>100 kDa) can only be released from vesicles if the latter disintegrate, but not through small pores or channels. Second, if vesicles only have pores, with progressive release the vesicle size distribution should not change, since there is no difference in size between a full and an empty vesicle. On the other hand, if the vesicles are disintegrated by the toxin carpet and fragmented into micellar lipid-protein aggregates, the particle distribution in the sample is expected to undergo a detectable shift toward smaller sizes. Some testable characteristics of the pore-forming model and the detergent model are listed in Fig. 3, which summarizes features of the two hypotheses on the pH-dependent mechanism by which Cyt1A permeabilizes lipid membranes.

FIG. 3.

The two hypothetical modes of action of Cyt1A. (1) The soluble toxin (shaded) diffuses in the extracellular phase. (2) During the approach to the membrane (lipid molecules are depicted as white circles with two zigzag tails), the toxin changes conformation and binds to the lipids. (3) The toxin molecules either insert into the lipid bilayer, where they form oligomeric pores, or lie (possibly in aggregates) splayed out on the surface of the membrane, which may have fragmented into toxin-lipid complexes. Intracellular molecules (black circles) leak either through the pores or through introduced lipid packing faults.

It should be pointed out that the pore-forming and detergent models are not mutually exclusive. Each can operate at different toxin concentrations or on different time scales. While at low concentrations the toxin may form oligomeric pores, at high toxin/lipid ratios the membrane may not be able to accommodate the large number of associated toxin molecules and, thus, breaks up. The issue of concentration is not trivial, and it might be one reason for the difficulties in reconciling the in vivo data with those obtained in vitro. In experiments in which one measures the effect of toxin on either cells, liposomes, or the whole organism, the concentrations used can be low, typically on the order of 10 nM, but the information obtained can rarely reveal anything about the molecular mechanism. In contrast, direct observation of the toxin molecule itself (i.e., its conformation, aggregation state, or another structural feature) usually necessitates the use of higher concentrations, typically 1 μM. Consequently, the latter experiments are prone to the criticism of the use of nonphysiological conditions. As for the simultaneous operation of the two mechanisms on different time scales, the apparent cation-selective channels may be only the first, temporary step in permeabilization of the membrane. Indeed, Schwarz and Robert (36) calculated that a single pore with an area of 0.3 nm2 and a lifetime of 15 ms would be sufficient to completely deplete a vesicle of its contents. Disintegration of the vesicle may follow after the leakage of small molecules.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

In spite of the commercial use of the toxin Cyt1A from B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis as a mosquito- and blackfly-specific insecticide, and despite a number of research studies published in entomological and biochemical journals, the mechanism of action of this powerful toxin remains a controversial subject. The focus of this article has been on in vitro biochemical and biophysical approaches that deal with Cyt1A structure and function at the molecular level. The current hypothesis of Cyt1A's mode of action and available data were critically evaluated. Notably, some recent observations call for an alternative model or at least for amending the pore-forming model. The hypothesis of a detergent-like action of Cyt1A has been considered, together with suggestions for its experimental testing.

This review may yield more questions than answers, but one of the goals of the author was to stimulate new experiments aimed at elucidating the mode of action of the Cyt toxins. Future work on Cyt1A is warranted for several reasons. (i) Cyt1A has a potential use in medicine: with appropriate targeting and activating systems, it can be employed to selectively destroy individual cell populations (1). (ii) Knowledge of Cyt1A's mechanism of action may bring improvements in formulation of B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis-based pesticides with increased insecticidal efficacy. (iii) Last but not least, future results may shed light on the mechanisms of membrane permeabilization and membrane damage by proteins that do not transverse the lipid bilayer.

Acknowledgments

This material is based, in part, on work supported by the Cooperative State Research, Education, and Extension Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, under agreement no. 2001-35302-10138, with additional support from Oak Ridge Associated Universities. Discussions with David J. Ellar (who was kind enough to share new manuscripts before publication), Marianne Pusztai-Carey, and Paul S. Russo are greatly appreciated. I also thank two anonymous reviewers who significantly contributed to the final form of this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-yahyaee, S. A., and D. J. Ellar. 1996. Cell targeting of a pore-forming toxin, CytA delta-endotoxin from Bacillus thuringiensis subspecies israelensis, by conjugating CytA with anti-Thy 1 monoclonal antibodies and insulin. Bioconjug. Chem. 7:451-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butko, P., M. Cournoyer, M. Pusztai-Carey, and W. K. Surewicz. 1994. Membrane interactions and surface hydrophobicity of Bacillus thuringiensis delta-endotoxin CryIC. FEBS Lett. 340:89-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butko, P., F. Huang, M. Pusztai-Carey, and W. K. Surewicz. 1996. Membrane permeabilization induced by cytolytic delta-endotoxin CytA from Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis. Biochemistry 35:11355-11360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butko, P., F. Huang, M. Pusztai-Carey, and W. K. Surewicz. 1997. Interaction of the delta-endotoxin CytA from Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis with lipid membranes. Biochemistry 36:12862-12868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang, C., Y. M. Yu, S. M. Dai, S. K. Law, and S. S. Gill. 1993. High-level cryIVD and cytA gene expression in Bacillus thuringiensis does not require the 20-kilodalton protein, and the coexpressed gene products are synergistic in their toxicity to mosquitoes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:815-821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chilcott, C. N., and D. J. Ellar. 1988. Comparative toxicity of Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis crystal proteins in vivo and in vitro. J. Gen. Microbiol. 134:2551-2558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chow, E., G. J. P. Singh, and S. S. Gill. 1989. Binding and aggregation of the 25-kilodalton toxin of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis to cell membranes and alteration by monoclonal antibodies and amino acid modifiers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 55:2779-2788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delecluse, A., J. F. Charles, A. Klier, and G. Rapoport. 1991. Deletion by in vivo recombination shows that the 28-kilodalton cytolytic polypeptide from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis is not essential for mosquitocidal activity. J. Bacteriol. 173:3374-3381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.deLello, E., W. K. Hanton, S. T. Bishoff, and D. W. Misch. 1984. Histopathological effects of Bacillus thuringiensis on the midgut of tobacco worm larvae (Manduca sexta): low doses compared with fasting. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 43:169-181. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drobniewski, F. A., and D. J. Ellar. 1988. Toxin-membrane interactions of Bacillus thuringiensis delta-endotoxin. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 16:38-40. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Du, J., B. H. Knowles, J. Li, and D. J. Ellar. 1999. Biochemical characterization of Bacillus thuringiensis cytolytic toxins in association with a phospholipid bilayer. Biochem. J. 338:185-193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Earp, D. J., and D. J. Ellar. 1987. Bacillus thuringiensis var. morrisoni strain PG14: nucleotide sequence of a gene encoding a 27-kDa crystal protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 15:3619.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellar, D. J. 2002. The insecticidal proteins of Bacillus thuringiensis, p. 179-189. In M. Ohba, O. Nakamura, E. Mizuki, and T. Akao (ed.), BT100: proceedings of a centennial symposium commemorating Ishikawa’s discovery of Bacillus thuringiensis, Kurume, Japan, 1 to 3 November 2001.

- 14.Falnes, P. O., and K. Sandvig. 2000. Penetration of protein toxins into cells. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 12:407-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fancy, D. A., and T. Kodadek. 1999. Chemistry for the analysis of protein-protein interactions: rapid and efficient cross-linking triggered by long wavelength light. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:6020-6024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Federici, B. A. 1995. The future of microbial insecticides as vector control agents. J. Am. Mosquito Control Assoc. 11:260-268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fink, A. L., L. J. Calciano, Y. Goto, T. Kurotsu, and D. R. Palleros. 1994. Classification of acid denaturation of proteins: intermediates and unfolded states. Biochemistry 33:12504-12511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gazit, E., N. Burshtein, D. J. Ellar, T. Sawyer, and Y. Shai. 1997. Bacillus thuringiensis cytolytic toxin associates specifically with its synthetic helices A and C in the membrane bound state. Implications for the assembly of oligomeric transmembrane pores. Biochemistry 36:15546-15554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gazit, E., and Y. Shai. 1993. Structural characterization, membrane interaction, and specific assembly within phospholipid membranes of hydrophobic segments from Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis cytolytic toxin. Biochemistry 32:12363-12371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grgacic, E. V., and H. Schaller. 2000. A metastable form of the large envelope protein of duck hepatitis B virus: low-pH release results in a transition to a hydrophobic, potentially fusogenic conformation. J. Virol. 74:5116-5122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guerchicoff, A., R. A. Ugalde, and C. P. Rubinstein. 1997. Identification and characterization of a previously undescribed cyt gene in Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2716-2721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haider, M. Z., and D. J. Ellar. 1989. Mechanism of action of Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal delta-endotoxin: interaction with phospholipid vesicles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 978:216-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ibarra, J. E., and B. A. Federici. 1986. Parasporal bodies of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. morrisoni (PG-14) and Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis are similar in protein composition and toxicity. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 34:79-84. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knowles, B. H., M. R. Blatt, M. Tester, J. M. Horsnell, J. Carroll, G. Menestrina, and D. J. Ellar. 1989. A cytolytic delta-endotoxin from Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis forms cation-selective channels in planar lipid bilayers. FEBS Lett. 244:259-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knowles, B. H., and D. J. Ellar. 1987. Colloid-osmotic lysis is a general feature of the mechanism of action of Bacillus thuringiensis delta-endotoxins with different insect specificity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 924:509-518. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knowles, B. H., P. J. White, C. N. Nicholls, and D. J. Ellar. 1992. A broad-spectrum cytolytic toxin from Bacillus thuringiensis var. kyushuensis. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 248:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koni, P. A., and D. J. Ellar. 1993. Cloning and characterization of a novel Bacillus thuringiensis cytolytic delta-endotoxin. J. Mol. Biol. 229:319-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li, J., P. A. Koni, and D. J. Ellar. 1996. Structure of the mosquitocidal delta-endotoxin CytB from Bacillus thuringiensis ssp. kyushuensis and implications for membrane pore formation. J. Mol. Biol. 257:129-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maddrell, S. H., J. A. Overton, D. J. Ellar, and B. H. Knowles. 1989. Action of activated 27,000 Mr toxin from Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis on Malpighian tubules of the insect Rhodnius prolixus. J. Cell Sci. 94:601-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Narva, K. E., J. Payne, K. A. Uyeda, C. J. Stalder, and T. E. Michaels. July1995. Bacillus thuringiensis isolate PS201T6 toxin. U.S. patent 5436002.

- 31.Nicholls, P., P. Butko, and B. Tattrie. 1995. Topology of cytochrome c oxidase-containing proteoliposomes: probes, proteins and pH gradients. J. Liposome Res. 5:371-398. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Promdonkoy, B. 1999. Ph.D. thesis. Cambridge University, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 33.Promdonkoy, B., and D. J. Ellar. 2000. Membrane pore architecture of a cytolytic toxin from Bacillus thuringiensis. Biochem. J. 350:275-282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ptitsyn, O. B., R. H. Pain, G. V. Semisotnov, E. Zerovnik, and O. I. Razgulyaev. 1990. Evidence for a molten globule state as a general intermediate in protein folding. FEBS Lett. 262:20-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schnepf, E., N. Crickmore, J. Van Rie, D. Lereclus, J. Baum, J. Feitelson, D. R. Zeigler, and D. H. Dean. 1998. Bacillus thuringiensis and its pesticidal crystal proteins. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:775-806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwarz, G., and C. H. Robert. 1992. Kinetics of pore-mediated release of marker molecules from liposomes or cells. Biophys. Chem. 42:291-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shai, Y. 1995. Molecular recognition between membrane-spanning polypeptides. Trends Biochem. Sci. 20:460-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Slaney, A. C., H. L. Robbins, and L. English. 1992. Mode of action of Bacillus thringiensis toxin CryIIIA: an analysis of toxicity in Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Say) and Diabrotica undecimpunctata howardi Barber. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 22:9-18. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swietnicki, W., R. Petersen, P. Gambetti, and W. K. Surewicz. 1997. pH-dependent stability and conformation of the recombinant human prion protein PrP(90-231). J. Biol. Chem. 272:27517-27520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Szabo, E., J. Murvai, P. Fabian, F. Fabian, M. Hollosi, J. Kajtar, Z. Buzas, M. Sajgo, S. Pongor, and B. Asboth. 1993. Is an amphiphilic region responsible for the haemolytic activity of Bacillus thuringiensis toxin? Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 42:527-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thiery, I., A. Delecluse, M. C. Tamayo, and S. Orduz. 1997. Identification of a gene for Cyt1A-like hemolysin from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. medellin and expression in a crystal-negative B. thuringiensis strain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:468-473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomas, W. E., and D. J. Ellar. 1983. Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis crystal delta-endotoxin: effects on insect and mammalian cells in vitro and in vivo. J. Cell Sci. 60:181-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomas, W. E., and D. J. Ellar. 1983. Mechanism of action of Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis insecticidal delta-endotoxin. FEBS Lett. 154:362-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Waalwijk, C., A. M. Dullemans, M. E. van Workum, and B. Visser. 1985. Molecular cloning and the nucleotide sequence of the Mr 28,000 crystal protein gene of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis. Nucleic Acids Res. 13:8207-8217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ward, E. S., D. J. Ellar, and C. N. Chilcott. 1988. Single amino acid changes in the Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis delta-endotoxin affect the toxicity and expression of the protein. J. Mol. Biol. 202:527-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wirth, M. C., G. P. Georghiou, and B. A. Federici. 1997. CytA enables CryIV endotoxins of Bacillus thuringiensis to overcome high levels of CryIV resistance in the mosquito Culex quinquefasciatus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:10536-10540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu, D., J. J. Johnson, and B. A. Federici. 1994. Synergism of mosquitocidal toxicity between CytA and CryIVD proteins using inclusions produced from cloned genes of Bacillus thuringiensis. Mol. Microbiol. 13:965-972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]