Abstract

16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) clone library analysis was conducted to assess prokaryotic diversity and community structural changes within a surficial sediment core obtained from an Antarctic continental shelf area (depth, 761 m) within the Mertz Glacier Polynya (MGP) region. Libraries were created from three separate horizons of the core (0- to 0.4-cm, 1.5- to 2.5-cm, and 20- to 21-cm depth positions). The results indicated that at the oxic sediment surface (depth, 0 to 0.4 cm) the microbial community appeared to be dominated by a small subset of potentially r-strategist (fast-growing, opportunistic) species, resulting in a lower-than-expected species richness of 442 operational taxonomic units (OTUs). At a depth of 1.5 to 2.5 cm, the species richness (1,128 OTUs) was much higher, with the community dominated by numerous gamma and delta proteobacterial phylotypes. At a depth of 20 to 21 cm, a clear decline in species richness (541 OTUs) occurred, accompanied by a larger number of more phylogenetically divergent phylotypes and a decline in the predominance of Proteobacteria. Based on rRNA and clonal abundance as well as sequence comparisons, syntrophic cycling of oxidized and reduced sulfur compounds appeared to be the dominant process in surficial MGP sediment, as phylotype groups putatively linked to these processes made up a large proportion of clones throughout the core. Between 18 and 65% of 16S rDNA phylotypes detected in a wide range of coastal and open ocean sediments possessed high levels of sequence similarity (>95%) with the MGP sediment phylotypes, indicating that many sediment prokaryote phylotype groups defined in this study are ubiquitous in marine sediment.

Many aerobic and facultatively anaerobic isolates from cold marine sediment have been shown to be psychrophilic (41, 60), and molecular analysis of coastal polar sediments also indicates the presence of a rich uncultivated prokaryotic diversity at continually low temperatures (43) and in sediment in general (34). The bacterial community of Svalbard fjord sediment was dominated by delta and gamma proteobacteria and smaller numbers of many other bacterial groups (38, 39). Ravenschlag et al. (38) also used fluorescent in situ hybridization and rRNA hybridization to determine the phylogenetic composition of prokaryotes in the top 5 cm of Svalbard fjord sediment. A bacterium-specific fluorescent in situ hybridization probe hybridized to 65% of detectable cells on average, while fewer than 5% of cells belonged to the Archaea. Overall, about 58% of microscopically detectable cells (24% of the total direct count) and 45% of bacterial rRNA could be assigned to known taxonomic groups including the Proteobacteria and Flavobacteria, results which compared well with clone library data (39). Results also support the contention that most benthic bacteria are autochthonous, not merely accumulating from the pelagic zone. Even in the light of these data, we still know relatively little about prokaryotic diversity, distribution, and function within oceanic sediments. By comparison, extensive analysis of pelagic prokaryotic communities indicates the presence of several cultured and uncultured groups, which are clearly ubiquitous (15, 18, 35). For example, marine group I of the Crenarchaeota, which appears to dominate bacterioplankton in the mesopelagic zone (200- to 1,000-m depth) of the ocean (25) also may be a common community member in surficial sediment (57). Theoretically, benthic communities should also contain many other ubiquitous, broadly distributed prokaryotic groups, since environmental conditions (temperature, nutrient availability and supply, and pressure) and processes (sulfate, iron and nitrate reduction, and carbon mineralization, etc.) can be considered to be generally similar over wide tracts of the oceanic seabed.

Microbial community structure analysis can be extended to give us an understanding of functional and biogeographical relationships (49), and such data are vital for an improved understanding of benthic ecosystem processes and the role that the benthos plays in overall oceanic processes. The analysis of clone libraries created from 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) amplified from environmental DNA can be used to assess community structure and diversity at the highest possible resolution, with 16S rDNA gene data sets providing a qualitative guide to the microbial composition of a given sample. Several bacterial 16S rDNA clone libraries have been constructed from marine and marine-derived sediments (6, 17, 30, 31, 34, 39, 54, 56); however, many of these are quite small and provide only a cursory examination of the microbial community present. More-detailed 16S rDNA data sets better allow the construction of specific probes, as a greater part of the inherent diversity of subgroups has been sampled. Specific probes then could be used in developing techniques such as 5′-nuclease PCR assays (52) and DNA microarrays (45) for rapid detection and quantification. In addition, more-detailed information would also indicate which prokaryote groups are important in surficial oceanic sediment and how the abundance of these groups varies under different environmental conditions.

In research on Antarctic continental shelf surficial sediment (5), we demonstrated that the benthic prokaryotic community present in Antarctic continental shelf sediments located below the Mertz Glacier Polynya (MGP) was metabolically active, contained a predominantly psychrophilic microbial community, and had well-defined and distinct structural characteristics. rRNA hybridization data indicated that Proteobacteria, Archaea, Flavobacteria, and Planctomycetales were abundant in MGP sediment cores and exhibited similar levels of abundance and zonation across the MGP shelf sediment area sampled. A substantial proportion of the benthic microbial community was not covered by the RNA probes applied, suggesting that many other prokaryote groups were also present. One hypothesis we wished to test was that community structural changes revealed by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) analysis can also be revealed by 16S rDNA clone library analysis, thus providing a more detailed impression of community structure in MGP sediment samples. With these data available, biogeographical comparisons of microbial communities of different marine sediment previously analyzed by clone library analysis of 16S rDNA sequences can also be compared and thus used to test the hypothesis that, like the pelagic environment, marine sediment contains many ubiquitous prokaryotic groups.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling.

A 21- by 1-cm (diameter) core was aseptically extracted from the central unperturbed section of a larger sediment core (5 m in length), the geology and paleochronology of which had been previously examined (core 10GC01 [18]). The large core was obtained from the MGP (66°31.86′S, 143°38.30′E) at a depth of 761 m during the Italian-Australian geoscience research cruise AGSCO survey 217 on the RV Tangaroa in February 2000 by using a gravity corer with a 1-metric-ton head unit. The sample was stored frozen at −20°C until processed.

DNA extraction.

The frozen core was sectioned at 1-cm intervals below 3 cm. The top of the 3 cm of core was sectioned in finer intervals of about 0.4 to 0.5 cm. DNA was extracted from each slice by the method of Rochelle et al. (40). The DNA samples were then further purified with Chroma Spin+TE-1000 columns (Clontech) and stored at −20°C before use. DNA yields were generally 50 to 70% higher (with greater purity) than what was found if a bead beating protocol (6) was used.

Clone library construction and sequencing.

The universal 16S rDNA primers 519f (5′-CAGCMGCCGCGGTAATAC-3′) and 1492r (5′-TACGGYTACCTTGTTACGAC-3′) were used to amplify 16S rDNAs from prokaryotes from the sediment DNA. PCR and clone library construction were carried out by procedures described previously (6), except sequencing was performed with the Beckman CEQ2000XL automated capillary sequencing system.

Phylogenetic analysis.

The 16S rDNA sequences generated in this study were compared to those in the National Center for Biotechnology Information nucleotide database by using BLAST searching. Sequences closely similar to those of clones as well as selected reference sequences were downloaded and manually aligned and analyzed by using BioEdit (version 5.0.9) (19). Phylogenetic trees were created by calculation of maximum-likelihood distances and by using the neighbor-joining algorithm through the BioEdit program. The statistical significance of phylotype groups within the various trees was tested by using bootstrap analysis with the Phylip programs SEQBOOT and CONSENSE (J. Felsenstein, University of Washington, Seattle). Trees were created from the NEIGHBOR output by using the program TREEVIEW. 16S rDNA sequences from Thermotoga maritimum and Coprothermobacter platensis were used as outgroup references on all trees.

Clone library analysis.

The depths of the subsamples taken from the core were 0 to 0.4 cm, 1.5 to 2.5 cm, and 20 to 21 cm; clone data sets arising from the samples were subsequently referred to as the 0-cm (surface), 2-cm, and 21-cm MGP sediment libraries. No prior dereplication of clones from the libraries by restriction enzyme-based analysis was performed before sequencing. The high diversity within the samples and the blunt-end cloning strategy made dereplication unnecessary. Chimeric sequences that were detected within the data set were discarded unless a confirmed contiguous sequence stretched for greater than 50% of the 1-kb 16S rDNA region investigated. After ignoring 18S rDNA (deriving almost entirely from species of the diatom genus Chaeotoceros) and chloroplast-derived 16S rDNA sequences, 338 to 369 clones from each MGP sediment sample were analyzed. Sequences which were 98% or greater in similarity where considered the same and grouped as a phylotype. This takes into account microvariations which may be induced by PCR and cloning (48) but also variations between 16S rDNA gene copies, which usually differ by 1% or less (29). The 16S rDNA phylotypes can in most cases be assumed to be an approximation of a prokaryote species as suggested by comparisons of 16S rDNA sequence divergence and genomic DNA hybridization levels (27). On the phylogenetic trees in Fig. 1 to 12, sequences are indicated by their species or clone designation, followed by the GenBank accession number and, for the MGP sediments, the number of clones detected in each clone library if it exceeds one. The BioEdit alignment files created in this study are available by e-mail from J. P. Bowman.

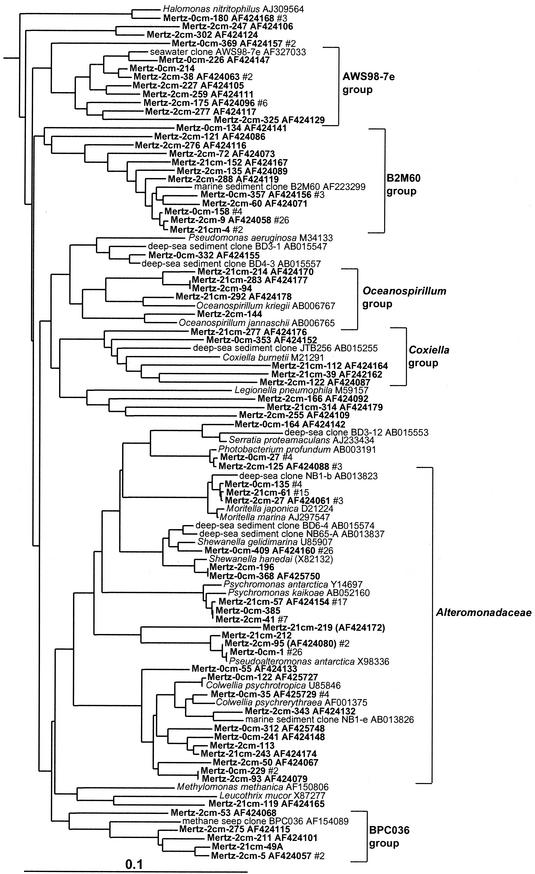

FIG. 1.

16S rDNA tree showing positions of mostly heterotrophic members of the gamma proteobacteria found within MGP sediment layers, including the AWS98-7e, B2M60, Oceanospirillum, Coxiella, Alteromonadaceae, and BPC036 phylotype groups.

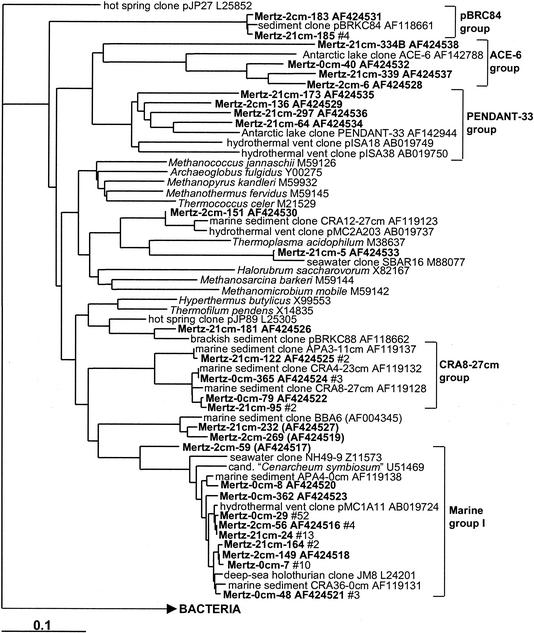

FIG. 12.

16S rDNA tree showing positions of members of the Archaebacteria found within MGP sediment layers, including the pBRC84, ACE-6, PENDANT-33, CRA8-27cm, and marine group I phylotype groups.

Species richness analysis.

Species richness was calculated by using the Rarefaction calculator, which is a web-based program written by C. J. Krebs and J. Brzustowski (University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada) and based at internet site http://www.biology.ualberta.ca/jbrzusto/rarefact.php. Species richness (S*1) was estimated by using the nonparametric model of Chao (10), i.e., S*1 = Sobs + (a2/2b), in which Sobs is the number of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) (16S rDNA clones) observed, a is the number of OTUs observed just once, and b is the number of OTUs observed only twice. The variance in the Chao calculations was computed by using the formula σ2 = (b[{a/4b}4 + {a/b}3 + {a/2b}2])2. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated by log transforming the data in order to obtain a normal distribution of means (9). Similarity between the clone libraries was calculated by using the LIBSHUFF.PL program as described by Singleton et al. (44), with ActivePerl version 5.08 on a IBM PC computer as the operating environment.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The 16S rDNA sequences generated in this study are available under GenBank accession numbers AF424054 to AF424538 and AF425747 to AF425762.

RESULTS

The sediment core was sampled from the MGP, which has high surface primary productivity and is a major source of Antarctic bottom water (4). Antarctic bottom water is quite nutrient rich (46) and not only plays a major role in the global ocean circulation but also contributes to enhanced biological activity in Antarctic coastal regions (3, 13, 51). Analysis of sediment cores from this area (depth range, 709 to 943 m) revealed an active, mostly psychrophilic microbial benthic community, which has well-defined community structural characteristics. Geological, paleochrononological, and geochemical lipid marker analyses otherwise indicated that the MGP sediment community had characteristics typical of modern open ocean sediment (5, 20).

Phylogenetic groups.

From the total of 1,046 clones analyzed, 496 phylotypes were defined, with 138, 255, and 194 phylotypes detected in the 0-, 2-, and 21-cm MGP sediments, respectively. A total of 76 phylotypes were found in two or all three libraries. From phylogenetic analysis, 56 significant prokaryotic 16S rDNA clusters (containing at least four clones [distance, <0.15; bootstrap value, >80%]) were found (Table 1). Since many of the clusters do not contain cultivated prokaryotes, they were designated arbitrarily with the names of corresponding 16S rDNA clones derived from earlier studies.

TABLE 1.

16S rDNA phylotype distribution through the MGP sediment core, with comparisons with other sediments for which extensive 16S rDNA phylogenetic data are available

| Taxonomic (phylogenetic) group | Phylotypic or taxonomic groupa | No. of phylotypes (no. of clones) in the following layer:

|

Phylotype group presence in the following sediment:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-0.4 cm | 1.5-2.5 cm | 20-21 cm | Deep seab | Arcticc | Antarctic in-shored | ||

| Bacteria | |||||||

| Gamma proteobacteria | Photobacterium | 1 (4) | 1 (3) | − | − | − | |

| Moritella | 1 (4) | 1 (3) | 1 (15) | − | − | − | |

| Shewanella | 2 (27) | 1 (1) | − | − | + | ||

| Psychromonas | 1 (1) | 1 (7) | 1 (17) | − | − | − | |

| Pseudoalteromonas | 1 (26) | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | + | − | − | |

| Colwellia | 6 (10) | 3 (4) | 1 (1) | − | − | + | |

| Oceanospirillum cluster | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | − | − | − | ||

| Coxiella cluster | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 3 (3) | − | − | + | |

| B2M60 cluster | 3 (8) | 7 (32) | 2 (3) | − | − | − | |

| BPC036 cluster | 3 (4) | 1 (1) | − | − | − | ||

| AWS98-7e cluster | 3 (4) | 6 (12) | − | − | − | ||

| BD3-6/JTB255 cluster | 20 (42) | 22 (40) | 4 (12) | + | + | + | |

| BD7-8 cluster | 3 (7) | 5 (11) | 2 (3) | + | − | + | |

| JTB23 cluster | 1 (1) | 2 (4) | − | − | + | ||

| sva0091 cluster | 2 (4) | 9 (10) | 3 (5) | + | + | + | |

| Ectothiorhodospiraceae | 1 (1) | 3 (5) | 1 (1) | − | − | − | |

| Beta Proteobacteria | Nitrosospira briensis | 1 (3) | 1 (2) | − | − | − | |

| Delta proteobacteria | Desulfosarcina group | 4 (4) | 17 (27) | 15 (31) | + | + | + |

| Desulfuromonas anilini group | 1 (2) | 3 (5) | − | − | − | ||

| Desulfobulbaceae | 1 (1) | 8 (9) | 3 (3) | + | + | + | |

| Desulfuromonas group | 2 (2) | 2 (6) | 1 (1) | − | + | − | |

| Myxobacteria | 2 (2) | 4 (5) | 2 (3) | + | + | − | |

| JTB38/Clear-9 group | 3 (3) | 4 (4) | + | + | + | ||

| Eel-TE1A4 group | 1 (2) | 2 (2) | 5 (6) | − | − | − | |

| Epsilon proteobacteria | Arcobacter group | 2 (13) | − | + | + | ||

| Thiomicrospira group | 2 (7) | 1 (3) | + | + | + | ||

| Alpha proteobacteria | Olavius losiae symbiont group | 1 (2) | 3 (5) | − | − | − | |

| Amaricoccus/JTB359 group | 1 (1) | 2 (6) | 1 (4) | − | − | + | |

| Ruegeria group | 2 (7) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | − | − | − | |

| Mertz cluster A | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | − | − | − | |

| JTB131 group | 1 (1) | 3 (5) | − | − | + | ||

| Acidobacteria | NKB17/sva0450 group | 5 (8) | 3 (5) | + | + | + | |

| Unafilliated | SAR406 group | 4 (5) | 3 (5) | + | − | − | |

| OP8 Group | NKB18 group | 4 (5) | 3 (5) | + | − | + | |

| Flavobacteria | NB1-m group | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 2 (2) | − | − | + |

| C. fermentans group | 1 (1) | 5 (10) | 7 (22) | + | + | + | |

| Zobellia | 2 (10) | 1 (1) | − | − | − | ||

| Tenacibaculum-Polaribacter group | 5 (17) | 4 (6) | 1 (1) | + | − | + | |

| Cellulophaga-Psychroserpens group | 8 (18) | 2 (2) | + | − | + | ||

| Spirochaetales | Spirochaeta | 2 (2) | 3 (6) | − | − | − | |

| Green sulfur bacteria | 2 (2) | 3 (5) | − | − | − | ||

| Planctomycetales | BD2-16 group | 2 (2) | 13 (13) | 13 (13) | + | + | + |

| Pirellula group | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 10 (14) | + | − | + | |

| ANAMMOX group | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | − | − | + | |

| Verrucomicrobia | BD2-18 group | 3 (4) | 1 (1) | + | + | + | |

| Verrucomicrobium group | 3 (6) | 2 (2) | − | − | − | ||

| Actinobacteria | JTB31/sva0389 group | 2 (11) | 3 (5) | 6 (17) | + | + | + |

| Gram positive | PAUC43f/BD2-11 group | 2 (2) | 4 (5) | − | − | + | |

| ACE-43 group | 2 (4) | 1 (2) | − | − | − | ||

| BURTON-30 group | 1 (1) | 1 (4) | − | − | − | ||

| Green nonsulfur | “Dehalococcoides” group | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | − | − | − | |

| BD3-16/PENDANT-37 group | 2 (2) | 8 (8) | 10 (16) | + | − | + | |

| OP11 groupe | 7 (7) | 13 (14) | − | − | − | ||

| Archaea | |||||||

| Euryarchaeota | pBRKC84 group | 1 (1) | 1 (4) | − | − | ||

| ACE-6 group | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | + | − | ||

| PENDANT-33 group | 1 (1) | 3 (4) | − | − | |||

| Crenarchaeota | APA3-11 cm group | 2 (4) | 2 (4) | + | − | ||

| Marine group I | 5 (67) | 2 (15) | 2 (5) | + | + | ||

Phylotype groups correspond to clusters of similar 16S rDNAs shown in the phylogenetic trees in Fig. 1 to 12.

Data are from references 30 and 31. Data are combined from several small clone libraries.

Data are from reference 39. No data for archaea are available because bacterium-specific primers were used.

Data are from Powell et al. (unpublished). Data are combined from two clone libraries derived from pristine and polluted sediments.

The OP11 group is not a single-phylotype group, it was included to show clonal abundance differences with sediment depth.

Gamma proteobacteria.

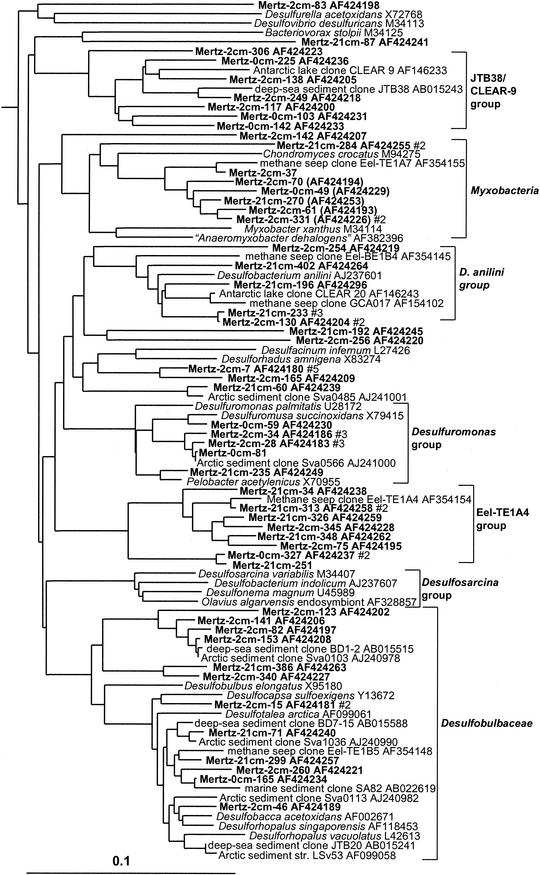

Gamma proteobacteria were the most commonly sampled group present within the Mertz core, representing 43, 42, and 23% of clones within the 0-, 2-, and 21-cm libraries, respectively, and comprising 16 major phylotype groups (Table 1). Several of these phylotype groups corresponded to chemoheterotrophic species and genera inhabiting cold marine ecosystems (sea ice, seawater, or sediment), including members of Photobacterium, Moritella, Psychromonas, Shewanella, Pseudoalteromonas, Colwellia, Pseudomonas, Halomonas, and Oceanospirillum (Fig. 1). A large proportion of gamma proteobacterial phylotypes detected, however, grouped into six clusters distinct from cultured species (Fig. 1 and 2). These groups included only clones detected previously in marine sediment samples, from both coastal and deep-sea sites. The largest group (BD3-6/JTB255 group) branched deeply within the gamma subclass and included the single highest concentration of phylotypes and clones found in the core samples (9% of total clones, making up 38 phylotypes). Two groups (BD7-8 and JTB148/Sva0091 groups) formed distinct lineages among predominantly phototrophic (families Chromatiaceae and Ectothiorhodospiraceae) and free-living and endosymbiotic sulfur oxidizers (Fig. 2). Two groups (B2M60 and AWS98-7e) include bacteria detected in sediment colonized by seagrass (12) and in seawater (15). A single phylotype group grouped in the beta proteobacteria and was closely related to the ammonia-oxidizing species Nitrosospira briensis (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

16S rDNA tree showing positions of putatively sulfur-oxidizing and other members of the gamma proteobacteria and beta proteobacteria found within MGP sediment layers, including the BD3-6/JTB255, Ectothiorhodospiraceae, BD7-8, and JTB148/sva0091 phylotype groups.

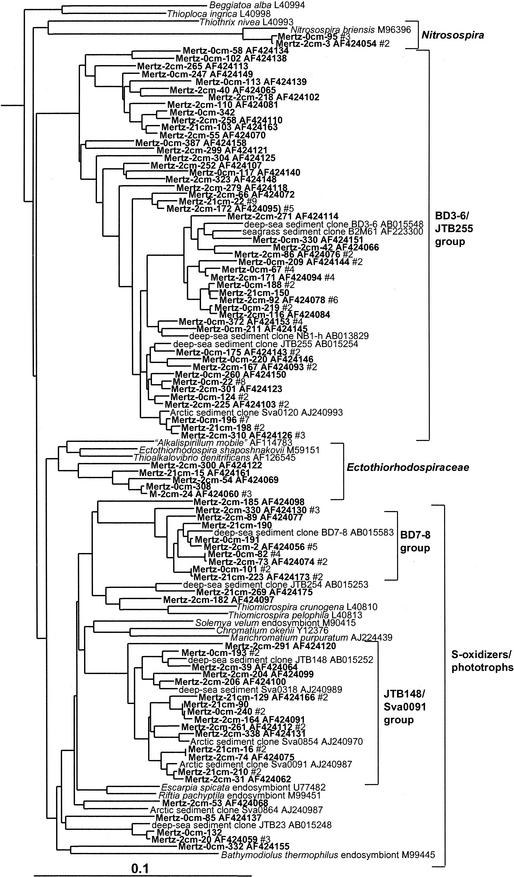

Delta and epsilon proteobacteria.

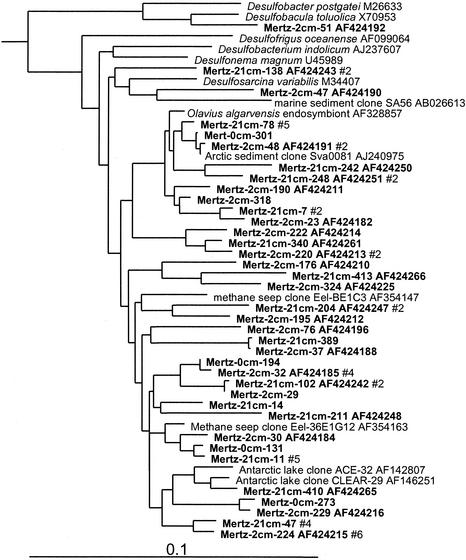

Levels of clone abundance indicated that delta and epsilon proteobacteria exhibited distinct zonation within MGP sediment, which concurred with RNA hybridization data (5). At the 0-cm horizon, 4% of clones grouped within the delta proteobacteria, but the abundance increased to 16 to 21% in the deeper samples. Most of the delta proteobacterial clones fell into seven phylotype groups (Table 1), the most significant of which was allied with the genus Desulfosarcina and relatives (6% of total clones) (Fig. 3). This extensive cluster included several clones previously detected in Antarctic lake sediment, Arctic fjord sediment, and methane seeps. Several significant phylotype groups clustered with various sulfate-reducing bacterial species or groups, including Desulfobacterium anilini and the family Desulfobulbaceae (Fig. 4). Some clones grouped among sulfur- and iron-reducing members of the Geobacteraceae, including the genera Pelobacter and Desulfuromusa. Several clones also grouped among the Myxobacteria group, which from the studies of Sanford et al. (43) includes strains capable of anaerobic growth (Fig. 4). Three distinct clusters (the Eel-TE1A4, BD1-2/Sva0103, and JTB38/Clear-9 groups) made up only of clones were also found. These groups contained clones previously found in a variety of other marine and marine-derived sediments (Fig. 4).

FIG. 3.

16S rDNA tree showing positions of delta proteobacteria found within MGP sediment layers, including the JTB38/Clear-9, Myxobacteria, Desulfobacterium anilini, Desulfuromonas, Eel-TE1A4, BD1-2/sva0103, and Desulfobulbaceae phylotype groups.

FIG. 4.

16S rDNA tree showing positions of members of the Desulfosarcina group and of the genus Desulfobacula found within MGP sediment layers.

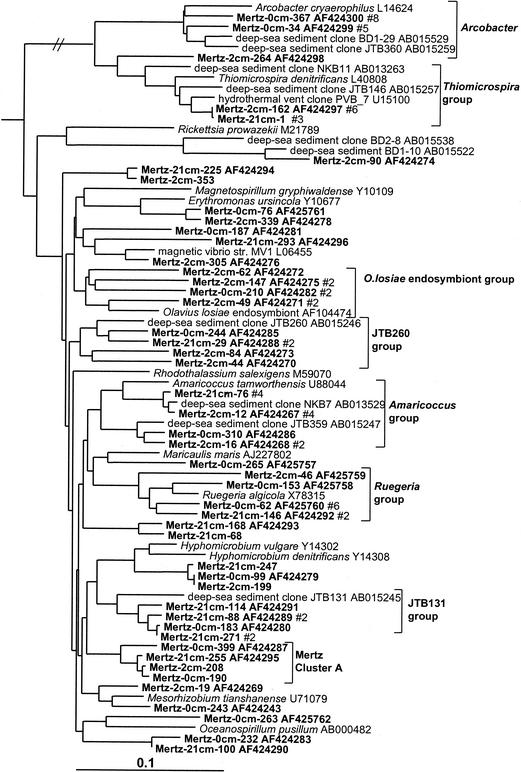

Clear zonation of epsilon proteobacteria was also evident in the MGP sediment core (Table 1; Fig. 5), with the surface 0-cm library containing several clones affiliated with the genus Arcobacter. The Arcobacter group was absent in the deeper libraries, which instead contained a group closely allied to the sulfur-reducing species Thiomicrospira denitrificans (Fig. 2). Both groups also contained a number of clones derived from a variety of deep-sea and hydrothermal sediments.

FIG. 5.

16S rDNA tree showing positions of members of the epsilon and alpha proteobacteria found within MGP sediment layers, including the Arcobacter, Thiomicrospira, Olavius losiae endosymbiont, JTB260, Amaricoccus, Ruegeria, JTB131, and Mertz cluster A phylotype groups.

Alpha proteobacteria.

The clone abundance of alpha proteobacteria was evenly distributed throughout the core libraries (6% of total clones). The biodiversity was considerable, and only small phylotype groups were evident (Fig. 5). Three phylotype groups were made up only of clones, two of which included deep-sea clones (JTB131 and JTB260 groups) and another group which was so far unique to this study (Mertz cluster A) (Fig. 5). Some phylotypes grouped near nonmarine genera (e.g., Mesorhizobium, Amaricoccus, and Hyphomicrobium), although the phylogenetic distances (0.05 to 0.10) suggest that the phylotypes represent different genera.

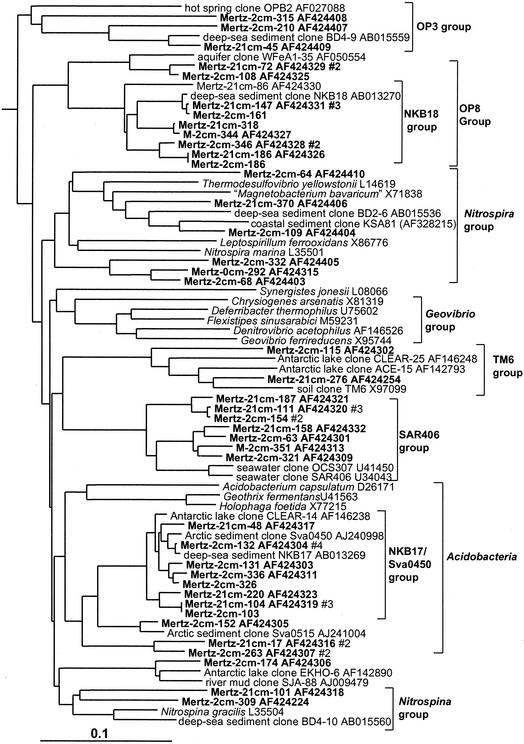

Acidobacteria and relatives.

In this study three distinct clusters of Acidobacteria (Fig. 6) were detected in the anoxic portions of the core; none were detected in the surface 0-cm library (Table 1). The most significant group (NKB17/Sva0450 group) was tightly associated with other clones found in the deep sea, a coastal Arctic fjord sample, and anoxic sediment of a brackish Antarctic lake (Fig. 6). Mertz clones also formed two other smaller groups, one of which included the Arctic fjord clone sva0515. Several clones were also associated with the Nitrospira group (Fig. 6). Within this group one clone branched with deep-sea clone BD2-6 (30) and coastal sediment clone KSA81 (referred to as candidate division KS-B [34]). Several phylotypes detected below the surface layer belonged to the SAR406 group (Fig. 6), which has been previously detected in a wide range of seawater samples (15), including the Southern Ocean (33).

FIG. 6.

16S rDNA tree showing positions of members of Acidobacteria and related lineages found within MGP sediment layers, including the NKB18 (OP8 group), SAR406, and NKB17/Sva0450 phylotype groups.

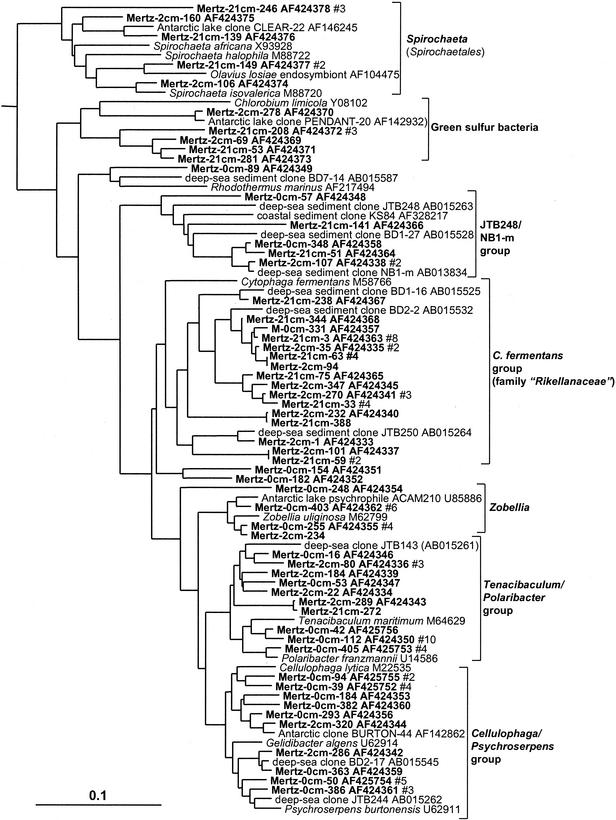

Flavobacteria, green sulfur bacteria, and spirochetes.

Flavobacteria displayed distinct zonation throughout the sediment core as indicated by the distribution of phylotypes in the different libraries as shown in Table 1. Within the 0-cm library, 45 out of 48 Flavobacteria clones grouped within the family Flavobacteriaceae concentrated into three phylotype groups represented by various marine aerobic and heterotrophic genera (Fig. 7). The incidence of Flavobacteriaceae declined with the depth of the sample, and they were practically absent in the 21-cm library. In the deeper samples several phylotype groups associated with predominantly anaerobic and facultatively aerobic heterotrophic taxa of the Cytophaga fermentans group (family “Rikellanaceae”) were evident (Fig. 7), which included several clones detected previously in deep-sea sediments (30). Another, more deeply branching lineage associated with deep-sea clones (JTB248/NB1-m group) included clones detected throughout the sediment core (Fig. 7). Two clone groups were found to branch within the green sulfur bacteria (Fig. 7), both of which are far removed (distance, 0.16 to 0.19) from the genus Chlorobium and its phototrophic relatives and thus could represent nonphototrophic members of this group. Several clones associated with the chemoheterotrophic and anaerobic genus Spirochaeta were found in the two deeper clone libraries (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

16S rDNA tree showing positions of members of the Flavobacteria, green sulfur bacteria, and spirochetes found within MGP sediment layers, including the Spirochaeta; Chlorobium-related; and flavobacterial JTB248/NB1-m, C. fermentans, Zobellia, Tenacibaculum-Polaribacter, and Cellulophaga-Psychroserpens groups. The latter three groups belong to the family Flavobacteriaceae.

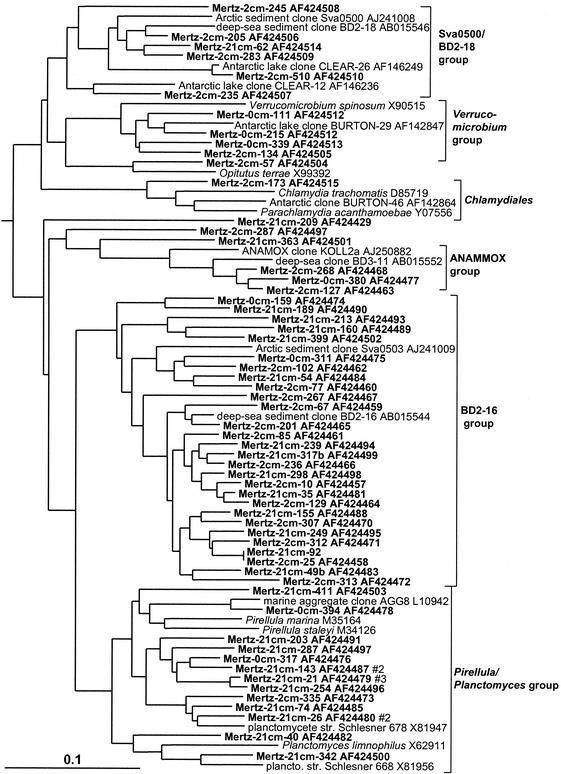

Planctomycetales and relatives.

The Planctomycetales were surprisingly diverse in the sediment core, with most of the phylotypes represented by only a single clone and forming three broad groups (Fig. 8). The first large group consisted only of clones, represented by deep-sea clone BD2-16 and the Arctic fjord clone sva0503 (Fig. 8). The BD2-16 group dominated Planctomycetales in the deeper clone libraries and was practically absent in the surface 0-cm library (Table 1). A second group, associated with the marine heterotrophic genus Pirellula and the species Planctomyces limnophilus, was also common in the 21-cm library but was overall more evenly distributed (Table 1; Fig. 8). The third group was most closely associated with the anaerobic ammonia-oxidizing cluster (ANAMMOX group) previously identified in wastewater systems and other sites (50). Mertz sediment clones falling into the Verrucomicrobia formed two main clusters. The first group contained clones mostly from the surface layer and included the aerobic oligotrophic and chemoheterotrophic genera Verrucomicrobium and Prosthecobacter. The second group contained only clones from anoxic deeper horizons of the core. This second group included clones from the deep sea as well as coastal sediments.

FIG. 8.

16S rDNA tree showing positions of members of the Planctomycetales and relatives found within MGP sediment layers, including the Sva0500/BD2-18, Verrucomicrobium, ANAMMOX, BD2-16, and Pirellula phylotype groups.

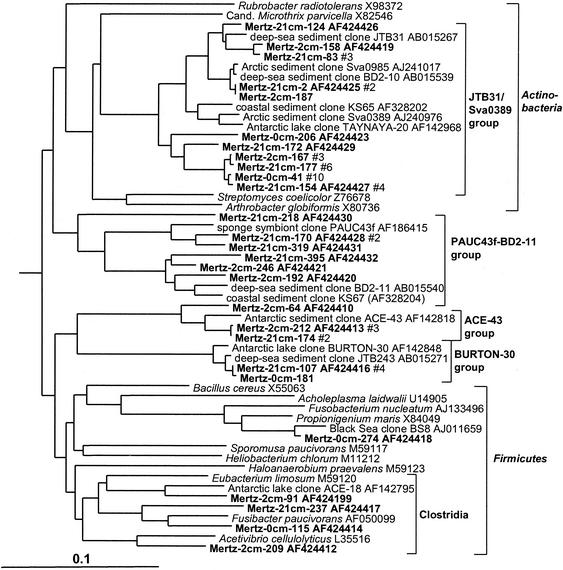

Gram-positive bacteria.

The Mertz sediment core contained an important phylotype group (3.8% of total clones) which formed a deep, distinct branch within the Actinobacteria (Fig. 9). This particular group also contained many sediment clones previously detected in deep-sea and coastal samples. Members of the low-G+C gram-positive bacteria (Bacillus-Clostridium group), by comparison, were much less abundant (Fig. 9). Three phylotype groups, represented by clones ACE-43, BURTON-30 and BD2-10, were also found, which form distinct rRNA branches (Fig. 9) and which according to bootstrap data do not appear to be definitively associated with any of the major gram-positive clades. The BURTON-30 group was previously found to make up about one-third of clones detected in Antarctic meromictic lake and anoxic marine basin sediments (6). The lineage represented by deep-sea clone BD2-10 included several 2- and 21-cm library clones. This group was referred to as candidate division KS-A in a study of coastal sediment off French Guiana (25).

FIG. 9.

16S rDNA tree showing positions of members of the gram-positive bacteria found within MGP sediment layers, including the JTB31/sva0389, PAUC43f/BD2-11, ACE-43, and BURTON-30 phylotype groups.

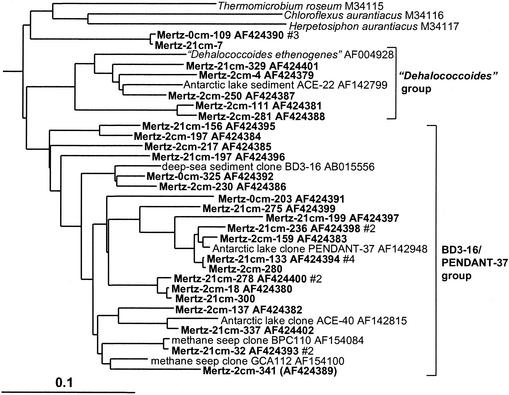

Green nonsulfur bacteria.

Clones grouped into two distinct clusters among the green nonsulfur bacteria (Fig. 10). The smaller group was associated with the anaerobe “Dehalococcoides ethenogenes” along with several clones found in a variety of marine, freshwater, and subsurface sediments (Fig. 10). The second larger group (BD3-16/PENDANT-37 group) included only cloned sequences, mostly deriving from anoxic sediment samples collected from deep-sea, coastal marine-derived, and terrestrial subsurface sites (Fig. 10), and seem to exhibit a distinct zonation in the core, as the clones were much more abundant in the deeper samples (Table 1).

FIG. 10.

16S rDNA tree showing positions of members of the green non-sulfur bacteria found within MGP sediment layers, including the “Dehalococcoides” and BD3-16/PENDANT-37 phylotype groups.

Unaffiliated groups.

In the sediment core libraries were repeatedly found many phylotypes which grouped in clusters distinct from established bacterial taxonomic groups (at least on the basis of 16S rDNA) but which were located in 16S rDNA clone groups established in other studies in which they were designated candidate divisions; these are referred to in this study simply as groups, as important aspects of their taxonomy have yet to be established (8). In this study several representatives of the OP3 (Fig. 6), OP8 (Fig. 6), and OP11 (Fig. 11) groups were found. The OP series designation is from Opal Pool, a hot spring in Yellowstone National Park, in which they were first discovered (23). These groups were strongly zonated in the sediment core, absent from the surface 0-cm library, and more common in the 21-cm library compared to the 2-cm library (Table 1). Mertz sediment clones formed many very long branches within the OP11 group (Fig. 11). The OP11 group is broadly distributed and has been detected in a variety of anoxic habitats (23), and the clones from this study were most closely associated with OP11 clones from deep-sea sediment and meromictic marine basins and lakes (Fig. 11). The clones falling into the OP8 group formed two distinct phylotype clusters (Fig. 6). The first cluster included clones found in deep-sea environments (represented by clone NKB18), while the second, smaller cluster contained a clone previously detected in an iron-rich terrestrial subsurface sediment (Fig. 6).

FIG. 11.

16S rDNA tree showing positions of members of the OP11 group found within MGP sediment layers, including known reference clones from terrestrial and marine sediments.

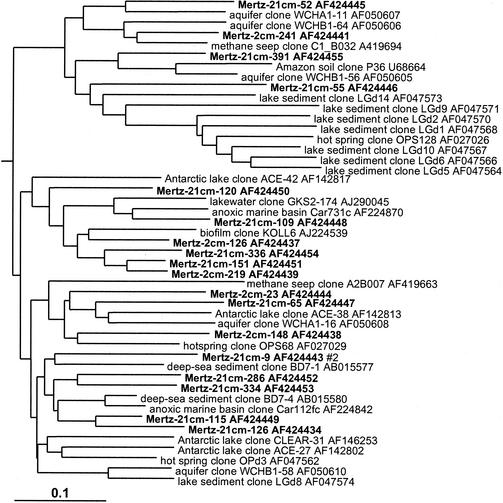

Archaea.

Marine group I (Crenarchaeota) predominated in the sediment core libraries, particularly in the surface 0-cm library (Table 1; Fig. 12), where it contributed about 18% of clones. A single abundant marine group I phylotype (comprising 79% of group I clones) was practically identical (0 to 3 nucleotide differences) to hydrothermal vent clone pMC1A11 (53) and was detected in all libraries. In the deeper samples archaeal diversity was considerably higher, with five euryarchaeotal and four other crenarchaeotal lineages found (Table 1). The CRA8-27cm/BBA6 phylotype cluster was the next most important crenarchaeotal group and includes clones previously detected in deep-sea and shelf sediments (57, 58) (Fig. 12). Euryarchaeotal phylotypes likewise grouped with clones previously found in different sediments. Clones mostly grouped into three long-branched lineages remote from cultivated taxa. These included an unusually deep clone group represented by brackish sediment clone pBRKC84 (S. C. Dawson and N. R. Pace, unpublished data) and two saline Antarctic lake clone groups (6) represented by ACE-6 and PENDANT-33 (Fig. 12). The latter groups have also been detected in a variety of anaerobic environments, including freshwater lake sediment, subsurface sediment and waters, rice paddy soil, and hydrothermal vents (data not shown). Only one clone each was found to group with marine groups II and III (Fig. 12), with the marine group III clone grouping closely with ocean sediment clones (e.g., CRA12-27cm [57]).

MGP sediment core clone library comparisons.

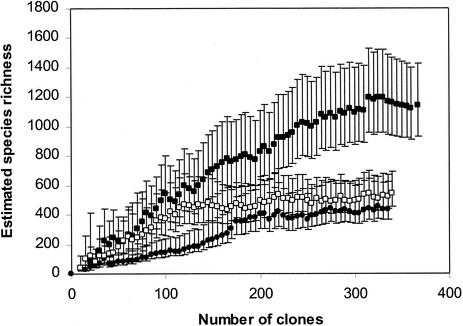

As the clone libraries were created simultaneously under nearly identical conditions, there was the opportunity for good comparative biodiversity analysis of MGP sediment layers by using statistical analyses to extrapolate species richness (24) and to quantify similarities or differences between the clone libraries (44). The relatively large size of the clone libraries makes species richness valid, as the species richness curves derived for each library (Fig. 13) approach an asymptote, which indicates that a final tally of the community members can be reliably estimated. Although they are useful in this study for intersample comparison, such comparisons cannot be made with other 16S rDNA clone library data sets owing to the different methodological strategies employed in creating them. In any case, most published data sets are too small to provide accurate values; i.e., most obtain only a nonasymptotic species richness curve, which may result in serious underestimates of species diversity. The estimated number of species was progressively compared to clone numbers in the order in which they were sampled in the library. The highest estimated number of species was clearly present in the 2-cm-deep sediment sample (Fig. 13), which contained 1,128 OTUs (95% CIs, 929 and 1,426). As this species richness curve does not clearly complete an asymptote, it is possible that the species richness has been underestimated. By comparison, the 0-cm (442 OTUs [95% CIs, 370 and 622]) and the 21-cm (541 OTUs [95% CIs, 455 and 691]) samples possessed similar levels of diversity, with the respective curves closely approaching if not fully completing an asymptotic curve (Fig. 13).

FIG. 13.

Species richness estimate curves derived from 16S rDNA clone library data for 0- to 0.4-cm (•), 1.5- to 2.5-cm (▪), and 20- to 21-cm (□) MGP sediment layers. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

Comparisons of homologous and heterologous coverage curves (see reference 44 for details) between the 2-cm library and the 0- and 21-cm libraries resulted in high P values (P = 0.69 and 0.81 [P values of <0.05 indicate that clone libraries are significantly different]), suggesting that the 2-cm library contained many phylotypes in common with both the 0- and 21-cm libraries. However, the reverse heterologous comparisons produced only low P values (P = 0.08 and 0.12), which suggest that the 2-cm library has many sequences not present in either of the other libraries. This result supports the species richness estimations and clearly indicates that at the 2-cm depth both surface and deeper core community members mix, resulting in a community with high taxonomic diversity and presumably high functional diversity. The 0- and 21-cm libraries, when compared, were not observed as statistically different (P = 0.15 and 0.22), which may be a reflection of several common phylotypes that occur throughout the core.

DISCUSSION

Methodological comparisons.

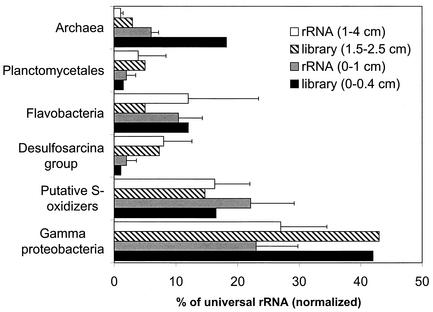

MGP sediment cores libraries can be validated to some extent with rRNA hybridization data (5), in which the relative abundances of gamma proteobacteria, putative sulfide-oxidizing bacteria (phylotype clusters BD7-8, JTB255/BD3-6, and sva0091 [Fig. 2]), the Desulfosarcina group, Flavobacteria, Archaea, gram-positive bacteria, and Planctomycetales were estimated. The variation that was found between clone library and RNA hybridization data perhaps indicates the extent of PCR bias distortion inherent in the clone libraries. This is most obvious for the archaeal abundance in the surface layer sample, which appeared to be overestimated threefold in the clone library analysis (Fig. 14). A positive correlation (+0.76) was found between the rRNA hybridization values and clone library abundances when the data were pooled, although the calculated regression was not robust (r2 = 0.57). Our data support the initial finding that sulfur- or sulfate-respiring bacteria dominate the MGP sediments. rRNA probe hybridization abundance data indicated that 16 to 27% and 2 to 9% of the community RNA (5) bound to a sulfur-oxidizer specific probe (GAM660 probe [38]) and to a probe specific to the Desulfosarcina group, respectively. Clones that have sequences complementary to the probes were also sampled frequently (14 to 15% and 4 to 7%, respectively) in samples of the same depth. Although the GAM660 probe suggests that the gamma proteobacterial phylotype groups could be involved in S oxidation, further cultivation analysis is required, as functionality is not always conserved between phylogenetic relatives. The information, however, provides a hypothesis in which cultivation approaches could be initially tested to obtain pure cultures of what appear to be abundant uncultivated members of the gamma proteobacteria.

FIG. 14.

Comparison between 16S rDNA library (percent of total clones) and rRNA hybridization (percent of universal rRNA) data for the abundances of various prokaryote groups in the MGP surface layer. RNA hybridization data are from reference 5. Error bars indicate standard deviations of means.

Diversity and phylogenetic comparisons.

Three areas of the core were analyzed in an attempt to understand community structures within the benthos. The 0-cm library, for example, was created to assess populations within the oxic to hypoxic surface zone of the core. Previous PCR-DGGE analysis of several MGP sediment cores indicated that the bacterial community appeared to be relatively homogenous below the oxic layer down to a depth of about 4 cm. Within this depth range the 2-cm level was selected, as it possessed a high level of metabolic activity (5). The 21-cm core section was analyzed because it exhibited significantly reduced metabolic activity and biomass and had distinctly different DGGE patterns compared to the surface layers (5). Since all three libraries were created at the same time, the differences in abundance found between different 16S rDNAs (with PCR and cloning artifacts [48, 59] being similar) could be considered qualitatively reliable when making comparisons between the MGP samples. The diversity within the Mertz cores was estimated to be highest within the 2-cm layer, approximately two- to threefold higher than that in the other layers analyzed (Fig. 13). This higher level of diversity may arise from active anaerobic decomposition and transformation of deposited organic matter which is encouraged by faunal bioturbation and current mixing of sediment, replenishing nutrients and energy sources (47). This is suggested by the fact that rates of sulfate and iron reduction, primary energy-yielding processes, appear to be highly active in marine sediment within this depth range (42). The reduced diversity observed at the 21-cm-deep layer may be due to much lower nutrient availability and thus a greater reliance on low-energy-yielding metabolic processes, as only poorer quality substrates are available (21). This occurrence could be a good example of the energy limitation hypothesis, which posits that the amount of energy available to an ecosystem limits the species richness by limiting the density of its individual taxa (26, 37). As biomass levels at the 21-cm depth were only 20 to 30% of those at the 2-cm depth, the hypothesis has validity in describing the reduced benthic microbial community species richness below the mixed surficial sediment layer. The hypothesis, however, completely fails to describe the lower diversity encountered within the oxic surface layer, which would be expected to have a ready supply of labile carbon and energy sources. It is possible that the surface community structure may be inhabited by various rapidly growing, nutritionally versatile, aerobic and facultatively anaerobic species (i.e., r strategists). This occurrence is indicated by the species richness curve (Fig. 13), which increased only gradually as the population was initially sampled, suggesting that a subset of dominant species with high levels of catchability (9) was present in the sample; indeed, the six most common phylotypes (Shewanella gelidimarina, Mertz_0cm_14; Pseudoalteromonas antarctica, Mertz_0cm_1; Tenacibaculum sp., Mertz_0cm_13; marine group I, Mertz_0cm_7 and Mertz_0cm_29; and novel actinobacterium, Mertz_0cm_41) collectively made up 34% of clones in the library. The first three of these phylotypes were successfully cultivated from the sediment at high most-probable-number dilutions, and each showed rapid growth at low temperature (5) on a wide variety of simple and complex substrates (data not shown). Additional samples need to be tested to determine if these results are consistent rather than being artifacts of the cloning and sampling process.

Overall, species richness calculations result in values comparable to calculations of diversity by using DNA renaturation kinetics, which have indicated that as many as 11,700 unique “genomes” were present within marine sediment sampled from a Norwegian fjord (55). Species richness was calculated in this study by using a somewhat more conservative approach, as each phylotype may actually represent a cluster of closely related species that share highly similar 16S rDNA sequences. However, the combined species richness determined by pooling all clones for the MGP sediment core was calculated at 4,350 (95% CIs, 3,715 and 5,594), which indicates that even with restricted sampling a potentially large proportion of the diversity present can be experimentally estimated.

Community structural shifts within the MGP core.

The difference in community structure within the Mertz core was most stark between the 0- and 21-cm libraries, with 27 bacterial and archaeal groups found in either library but not in both (Table 1). Only three groups were found to be present in the 0- and 21-cm libraries and were not detected in the 2-cm library, suggesting that these particular groups may be spread at levels throughout the core at or below the resolution limits of the library analysis. In the surface 0-cm library, several predominant phylotype groups were found (Table 1), including the family Alteromonadaceae (Shewanella, Moritella, Pseudoalteromonas, and Colwellia), the Arcobacter group, Nitrosospira, the Ruegeria group, the family Flavobacteriaceae, the Verrucomicrobium group, the actinobacterium JTB31/sva0389 group, and marine group I Crenarchaeota. These groups are all oxygen requiring or are closely related to aerobic taxa (as far as can be shown by phylogenetic comparisons), which have been isolated or detected within the pelagic zone, sea ice, or surficial sediment. For example, the genus Arcobacter and members of the Flavobacteria were found to be very abundant in Wadden Sea surface sediment (32). The clone abundance of the major 0-cm-depth taxa appear to decline with depth, with most not detected at a depth of 21 cm. The most abundant surface clone group, marine group I, was an exception, as it was found throughout the sediment core. This group has been shown to represent a major fraction of mesopelagic bacterioplankton (25) and is also common in deep-sea sediment (57). Heterotrophic aerobic and facultatively aerobic species found to dominate the surface sediment community belong to groups known to have strong capacities for degradation of complex organic matter (proteins and polysaccharide). For example, members of the families Alteromonadaceae and Flavobacteriaceae, which together constituted 34% of 0-cm library clones, have been shown to be important degraders of seawater dissolved organic carbon, have been found to be highly abundant in the Southern Ocean south of the Polar Front, and occur as the dominate bacterial populations in sea-ice algal assemblages (7, 28).

The differences between microbial communities in anoxic (2- and 21-cm libraries) and mostly oxic (0-cm library) sediment layers were quite evident. For example, the clonal abundance of delta proteobacteria increased fivefold between the 0- and 2-cm libraries, and many clone groups (OP8 and OP11 groups, SAR406 group, and ACE-43 group, etc.) (Table 1) were not detected within the 0-cm library. Previous DGGE analysis of the sediment core suggested that distinct but gradual community shifts occurred below 4 cm (5). With clone library analysis and its much higher level of resolution, few distinct gross differences between the 2- and 21-cm samples on the phylotype group level are obvious (Table 1); however, changes in clonal abundance were obvious across many phylotype groups. Apparent depth-related increases in clonal abundance occurred for the genus Psychromonas, the JTB131 group (alpha proteobacteria), the family “Rikenellaceae,” Spirochaeta, Chlorobium-related groups, the JTB31/sva0389 group (Actinobacteria), the Pirellula group, the OP8 and OP11 groups, and some groups of the Euryachaeota (Table 1). The phylotypes within this list, although clustering mostly within uncultured lineages, appear to be associated only with anoxic conditions, as they were generally not detected in the 0- to 0.4-cm layer. It is possible that the species distribution within the various phylotype groups changes substantially between the 2- and 21-cm depths. However, an insufficient number of clones were analyzed to be able discriminate differences reliably at the species level. At least 103 to 104 clones, as suggested by null theoretical models of soil bacterial diversity (14), and more sediment sampling would be required to be analyzed to observe individual phylotype distributions within the MGP sediments.

Biogeographical comparisons.

Biogeography as applied to prokaryotic distribution in the natural environment is still an undeveloped area. Staley and Gosink (49) suggested a logical model for biogeographical analysis which involves isolation of several strains from different sites with confirmation of species similarity by using molecular approaches such as DNA-DNA hybridization. For many environments the difficulties involved in cultivation make it possible to make comparisons only at higher taxonomic levels for most prokaryotes.

Although the microbial community structure in marine ecosystems varies at the microscale, owing to variable nutrient distribution (2), the same marine prokaryotic species and genera inhabit ecologically similar niches separated over wide geographical scales (18, 35, 62), with populations shifting in space and time depending on environmental fluctuations. Even though various physiological characteristics are not necessarily conserved within the phylogenetic groups found in this study (Table 1), the environmental conditions and energy sources available would tend not only to dictate microbial community composition and species richness but also to constrain the physiological characteristics of the community members. In the case of the MGP sediments, most community members must be cold adapted and generally able to grow anaerobically and subsist on exported primary produced carbon that is in various stages of decomposition. As much benthic life exists under essentially the same conditions as those of the MGP sediments (hypoxia, low temperature, sulfidogenesis, and faunal mixing of sediment, etc.), it would be expected that as for seawater, dominant groups of prokaryotes are broadly represented in marine sediment. Distributional comparisons of prokaryotes (1, 11, 22, 61) have only recently been possible as the 16S rDNA database has expanded sufficiently to cover most global prokaryote diversity. In this study, for example, although about 500 phylotypes were found, only a small minority represented taxonomically novel groups of bacteria (similarity to GenBank sequences of <0.90), suggesting that a large proportion of class-and higher-level prokaryotic lineages may already have been discovered, at least in the marine environment.

To determine the distribution of prokaryote groups detected in this survey, comparisons were made between the MGP libraries and libraries derived from other sediment samples collected from coastal, deep-sea, and marine locations. Phylotype comparisons (Table 2) were made at approximately the equivalents of intrageneric (<0.02) and intergeneric (<0.05) levels. At 16S rDNA dissimilarities of <0.02, genomic hybridization levels are often quite high, sometimes above the point which denotes prokaryote species boundaries (60 to 70%) and well within generic boundaries; however, owing to quantum evolution of 16S rDNAs (8), it is generally not possible to make accurate species-level comparisons by using 16S rDNA data alone. Regardless of this limitation, comparisons of this sort can reveal and define potentially ubiquitous bacterial groups.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of individual Mertz sediment 16S rDNA phylotype distributions in sediment samples from other regions

| Sediment clone library designationa | Sediment characteristics | Location | Depth (m) | No. of phylotypes compared | % Similarity at:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.02 | <0.05 | |||||

| OB3/BB2 | Pristine and polluted (hydrocarbons, heavy metals) | Brown Bay, O'Briens Bay, East Antarctica | 15-25 | 124 | 35 | 65 |

| sva | Sulfidogenic | Svalbard, Arctic (Hornsund fjord) | 155 | 69 | 32 | 61 |

| JTB | Calyptogena colony, cold methane seep | Japan Trench, Pacific Ocean | 6,437 | 38 | 32 | 47 |

| Eelb | Cold methane seep | Eel River Basin, United States | 500 | 17 | 29 | 65 |

| BD | Deep-sea trough and trench surficial sediment | Pacific Ocean trenches and troughs | 1,200-7,400 | 58 | 17 | 36 |

| Guaymas | Hydrothermally active, methane seep | Guaymas Basin, Mexico | 2,000 | 73 | 8 | 19 |

| BURTON | Meromictic, seasonally mixed, marine basin | Vestfold Hills, Antarctica | 16 | 56 | 1 | 23 |

| ACE | SO4-depleted, saline meromictic lake | Vestfold Hills, Antarctica | 21 | 45 | 9 | 18 |

| KSA | Highly mobile, Fe reducing | Coastal French Guiana | 1 | 61 | 3 | 25 |

MGP clone data were compared with those for other sediment clone libraries analyzed: BD (30), JTB (31), sva (39), OB3/BB2 (Powell et al., unpublished data), Eel (36), SA (56), BURTON and ACE (6), and KSA (34). DNA was extracted from sediment grabs, except for the sva (integrated DNA samples from sediment depths of 0 to 2, 3 to 6, and 8 to 11 cm), Eel (3-cm layers extruded from push or piston cores down to 22 cm), and KSA (10- to 30-cm section of a 1.2-m core) libraries.

Only delta proteobacterial clones were compared from the Eel library, as methanogens were not detected in MGP surficial sediment.

Compared to the combined MPG sediment phylotype list, the highest number of similar phylotypes (similarity at <0.02, 17 to 32%; similarity at <0.05, 36 to 65%) was found in sediment from Antarctic in-shore (S. M. Powell et al., unpublished data), Arctic fjord (39), and various deep-sea (30, 31) sites. Although ranging widely in depth, these sediments shared with Mertz sediment similar low temperatures (<3°C) and a dominance of sulfidogenic processes as suggested by the high abundance of gamma, delta, and epsilon proteobacteria. The similarity was much lower (Table 2) in environments that have characteristics not typical of most oceanic sediment. The French Guiana coastal sediments were nonsulfidogenic and subject to very rapid mixing (34), while the Antarctic marine-derived meromictic lake and marine basin sediments were chemically stratified stagnant water bodies, sulfide rich but sulfate depleted, separated from the ocean for 8,000 to 10,000 years (6). MGP sediments were also quite different from extensively characterized Guaymas Basin sediments, which are thermally active, hydrocarbon rich, and exposed to high terrigenous input (54).

Similarities between the MGP sediments and other sediments were found to coincide to a large degree in certain taxonomic groups, especially the Proteobacteria (Table 1). For example, a large proportion of delta proteobacteria found in methane-oxidizing sediments of the Eel River Basin (36) were quite similar to phylotypes in the MGP sediments (Fig. 3 and 4). The apparent high population of many of the gamma and delta proteobacteria in sediment, especially those involved in sulfur cycling, appears to increase the probability of them being detected in wide-ranging locations. On the other hand, certain phylogenetic groups do not show much if any similarity between different sediment samples (e.g., most clones of the Planctomycetales and Verrucomicrobia and many of the unaffiliated taxa [e.g., OP11 group and Euryarchaeota]), even though numerous phylotypes were detected in these groups. This may indicate that the distribution of certain prokaryotes is potentially endemic, with localized populations specifically adapted to the idiosyncratic properties of the given environment. Another equally likely interpretation is that these groups have not been sufficiently sampled. Finlay (16) suggested that the high abundance, short generation time, small size, and high dispersal rates of prokaryotes makes them unlikely to be endemic, as they are able to overcome large geographical barriers. Thus, only with extremely large clone libraries or, better still, by using a more specific targeting strategy (e.g., group-specific primers) will the actual distribution of rarer phylotypes be ascertained.

Conclusions.

This study examined closely the microbial community in a specific location on the ocean seafloor, with the community found to be very diverse and complex. The diversity was almost equivalent to what has been found in terrestrial soils (14). Local environmental conditions and cultivation studies (5) indicate that the community is highly cold adapted, and thus psychrophilic adaptations are present within many bacterial classes. Community structural shifts were evident between the thin oxic layer and the anoxic zone below; however, changes within the anoxic zone were more subtle, with the suggestion of different groups gradually become more dominant or, alternatively, declining with depth. The changes in community structure in the anoxic zone are possibly driven by nutrient availability, with lower-quality sources of carbon and energy leading to the attrition of prokaryotic groups common in the top layers. Comparisons made between the MGP sediment library and clone library data obtained from other sediments suggested that many prokaryote groups, taxons equivalent to the species to family level, were ubiquitously present in deep-ocean and trench sediments as well as coastal regions. (Table 1 and 2). Several prokaryote phylotype groups were found to be broadly distributed in disparate marine sediments (Table 1) found both in shallow and deep waters. The paucity of data means that many groups have been detected in only a few sediment samples so far, and thus more samples need to analyzed in detail before we can determine the true ubiquity and distribution of specific prokaryotic groups in the benthos. Further definition of major benthic prokaryotic groups will aid in the better understanding of microbial processes and interactions in marine sediment. Improved and more useful targeting and quantification of these groups will be achieved with molecular ecological techniques only now emerging.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Australian Research Council large grant A09905709 and by Antarctic Science Advisory Committee grants 1012 and 1065.

We thank Lisette Robertson and Peter Harris for providing the marine sediment core that was analyzed in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrews, J. H., and R. F. Harris. 2000. The ecology and biogeography of microorganisms of plant surfaces. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 38:145-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azam, F., and R. A. Long. 2001. Oceanography—sea snow microcosms. Nature 414:495-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bates, N. R., D. A. Hansell, C. A. Carlson, and L. I. Gordon. 1998. Distribution of CO2 species, estimates of net community production, and air-sea CO2 exchange in the Ross Sea polynya. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 103:2883-2896. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bindoff, N. L., G. D. Williams, and I. Allison. 2002. Sea-ice growth and water mass modification in the Mertz Glacier Polynya during winter. Ann. Glaciol. 33:399-406.

- 5.Bowman, J. P., S. A. McCammon, J. A. E. Gibson, L. Robertson, and P. D. Nichols. 2003. Prokaryotic metabolic activity and community structure in Antarctic continental shelf sediment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:2448-2462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Bowman, J. P., S. M. Rea, S. A. McCammon, and T. A. McMeekin. 2000. Diversity and community structure within anoxic sediment from marine salinity meromictic lakes and a coastal meromictic marine basin, Vestfold Hills, Eastern Antarctica. Environ. Microbiol. 2:227-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown, M. V., and J. P. Bowman. 2001. A molecular phylogenetic survey of sea-ice microbial communities (SIMCO). FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 35:267-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cavalier-Smith, T. 2002. The neomuran origin of archaebacteria, the negibacterial root of the universal tree and bacterial megaclassification. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52:7-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chao, A. 1987. Estimating the population size for capture-recapture data with unequal catchability. Biometrics 43:783-791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chao, A. 1984. Non-parametric estimation of the number of classes in a population. Scand. J. Stat. 11:265-270. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho, J. C., and J. M. Tiedje. 2000. Biogeography and degree of endemicity of fluorescent Pseudomonas strains in soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:5448-5456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cifuentes, A., J. Anton, S. Benlloch, A. Donnelly, R. A. Herbert, and F. Rodriguez-Valera. 2000. Prokaryotic diversity in Zostera noltii-colonized marine sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:1715-1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DiTullio, G. R., J. M. Grebmeier, K. R. Arrigo, M. P. Lizotte, D. H. Robinson, A. Leventer, J. B. Barry, M. L. VanWoert, and R. B. Dunbar. 2000. Rapid and early export of Phaeocystis antarctica blooms in the Ross Sea, Antarctica. Nature 404:595-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunbar, J., S. M. Barns, L. O. Ticknor, and C. R. Kuske. 2002. Empirical and theoretical bacterial diversity in four Arizona soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3035-3045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eilers, H., J. Pernthaler, J. Peplies, F. O. Glockner, G. Gerdts, and R. Amann. 2001. Isolation of novel pelagic bacteria from the German Bight and their seasonal contributions to surface picoplankton. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:5134-5142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finlay, B. J. 2002. Global dispersal of free-living microbial eukaryote species. Science 296:1061-1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gray, J. P., and R. P. Herwig. 1996. Phylogenetic analysis of the bacterial communities in marine sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:4049-4059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hagstrom, A., J. Pinhassi, and U. L. Zweifel. 2000. Biogeographical diversity among marine bacterioplankton. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 21:231-244. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hall, T. A. 1999. A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 41:95-98. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris, P. T., G. Brancolini, L. Armand, M. Busetti, R. J. Beaman, G. Giorgetti, M. Presti, and F. Trincardi. 2001. Continental shelf drift deposit indicates non-steady state Antarctic bottom water production in the Holocene. Mar. Geol. 179:1-8. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoehler, T. M., M. J. Alperin, D. B. Albert, and C. S. Martens. 2001. Apparent minimum free energy requirements for methanogenic Archaea and sulfate-reducing bacteria in an anoxic marine sediment. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 38:33-41. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hollibaugh, J. T., N. Bano, and H. W. Ducklow. 2002. Widespread distribution in polar oceans of a 16S rRNA gene sequence with affinity to Nitrosospira-like ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1478-1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hugenholtz, P., B. M. Goebel, and N. R. Pace. 1998. Impact of culture-independent studies on the emerging phylogenetic view of bacterial diversity. J. Bacteriol. 180:4765-4774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hughes, J. B., J. J. Hellmann, T. H. Ricketts, and B. J. M. Bohannan. 2001. Counting the uncountable: statistical approaches to estimating microbial diversity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4399-4406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karner, M. B., E. F. DeLong, and D. M. Karl. 2001. Archaeabacterial dominance in the mesopelagic zone of the Pacific Ocean. Nature 409:507-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaspari, M., S. O'Donnell, and J. Kercher. 2000. Energy, density, and constraints to species richness: ant assemblages along a productivity gradient. Am. Nat. 155:280-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keswani, J., and W. B. Whitman. 2001. Relationship of 16S rRNA sequence similarity to DNA hybridization in prokaryotes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51:667-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kirchman, D. L. 2002. The ecology of Cytophaga-Flavobacteria in aquatic environments. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 137:1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kroes, I., P. W. Lepp, and D. A. Relman. 1999. Bacterial diversity within the human subgingival crevice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:14547-14552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li, L., C. Kato, and K. Horikoshi. 1999. Bacterial diversity in deep-sea sediments from different depths. Biodivers. Conserv. 8:659-677. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li, L., C. Kato, and K. Horikoshi. 1999. Microbial diversity in sediments collected from the deepest cold-seep area, the Japan Trench. Mar. Biotechnol. 1:391-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Llobet-Brossa, E., R. Roselló-Mora, and R. Amann. 1998. Microbial community composition of Wadden Sea sediments as revealed by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2691-2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopez-Garcia, P., A. Lopez-Lopez, D. Moreira, and F. Rodriguez-Valera. 2001. Diversity of free-living prokaryotes from a deep-sea site at the Antarctic Polar Front. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 36:193-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Madrid, V. M., J. Y. Aller, R. C. Aller, and A. Y. Chistoserdov. 2001. High prokaryote diversity and analysis of community structure in mobile mud deposits off French Guiana: identification of two new bacterial candidate divisions. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 37:197-209. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mullins, T. D., T. B. Britschgi, R. I. Krest, and S. J. Giovannoni. 1995. Genetic comparisons reveal the same unknown lineages in Atlantic and Pacific bacterioplankton communities. Limnol. Oceanogr. 40:148-158. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orphan, V. J., K.-U. Hinrichs, W. Ussler III, C. K. Paull, L. T. Taylor, S. P. Sylva, J. M. Hayes, and E. F. Delong. 2001. Comparative analysis of methane-oxidizing Archaea and sulfate-reducing bacteria in anoxic marine sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:1922-1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paine, R. T. 1966. Food wed complexity and species diversity. Am. Nat. 100:65-75. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ravenschlag, K., K. Sahm, and R. Amann. 2001. Quantitative molecular analysis of the microbial community in marine Arctic sediments (Svalbard). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:387-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ravenschlag, K., K. Sahm, J. Pernthaler, and R. Amann. 1999. High bacterial diversity in permanently cold marine sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3982-3989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rochelle, P. A., B. A. Cragg, J. C. Fry, R. J. Parkes, and A. J. Weightman. 1994. Effect of sample handling on estimation of bacterial diversity in marine sediments by 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis. Bact. Genet. Ecol. 15:215-226. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rüger, H.-J. 1989. Benthic studies of the northwest African upwelling region: psychrophilic and psychrotrophic bacterial communities from areas with different upwelling intensities. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 57:45-52. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rysgaard, S., B. Thamdrup, N. Risgaard-Petersen, H. Fossing, P. Berg, P. B. Christensen, and T. Dalsgaard. 1999. Seasonal carbon and nutrient mineralization in a high-Arctic coastal marine sediment, Young Sound, Northeast Greenland. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 175:261-276. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanford, R. A., J. R. Cole, and J. M. Tiedje. 2002. Characterization and description of Anaeromyxobacter dehalogenans gen. nov., sp. nov., an aryl-halorespiring facultative anaerobic myxobacterium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:893-900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Singleton, D. A., M. A. Furlong, S. L. Rathbun, and W. B. Whitman. 2001. Quantitative comparisons of 16S rDNA gene sequence libraries from environmental samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4374-4376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Small, J., R. C. Douglas, F. J. Brockman, T. M. Straub, and D. P. Chandler. 2001. Direct detection of 16S rRNA in soil extracts by using oligonucleotide microarrays. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4708-4716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sohrin, Y., S. Iwamoto, M. Matsui, H. Obata, E. Nakayama, K. Suzuki, N. Handa, and M. Ishii. 2000. The distribution of Fe in the Australian sector of the Southern Ocean. Deep-Sea Res. I 47:55-84. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Soltwedel, T., and K. Vopel. 2001. Bacterial abundance and biomass in response to organism-generated habitat heterogeneity in deep-sea sediments. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 219:291-298. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Speksnijder, A. G. C. L., G. A. Kowalchuk, S. De Jong, E. Kline, J. R. Stephen, and H. J. Laanbroek. 2001. Microvariation artifacts introduced by PCR and cloning of closely related 16S rRNA gene sequences. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:469-472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Staley, J. T., and J. J. Gosink. 1999. Poles apart: biodiversity and biogeography of sea ice bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 53:189-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Strous, M., J. A. Fuerst, E. H. Kramer, S. Logemann, G. Muyzer, K. T. van de Pas-Schoonen, R. Webb, J. G. Kuenen, and M. S. Jetten. 1999. Missing lithotroph identified as new planctomycete. Nature 400:446-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strutton, P. G., F. B. Griffiths, R. L. Waters, S. W. Wright, and N. L. Bindoff. 2000. Primary productivity off the coast of East Antarctica (80-150°E): January to March 1996. Deep-Sea Res. Part II 47:2327-2362. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Suzuki, M. T., L. T. Taylor, and E. F. DeLong. 2000. Quantitative analysis of small-subunit rRNA genes in mixed microbial populations via 5′-nuclease assays. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4605-4614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takai, K., and K. Horikoshi. 1999. Genetic diversity of archaea in deep-sea hydrothermal vent environments. Genetics 152:1285-1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Teske, A., K. U. Hinrichs, V. Edgcomb, A. de Vera Gomez, D. Kysela, S. P. Sylva, M. L. Sogin, and H. W. Jannasch. 2002. Microbial diversity of hydrothermal sediments in the Guaymas Basin: evidence for anaerobic methanotrophic communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1994-2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Torsvik, V., R. Sorheim, and J. Goksoyr. 1996. Total bacterial diversity in soil and sediment communities—a review. J. Indust. Microbiol. 17:170-178. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Urakawa, H., K. Kita-Tsukamoto, and K. Ohwada. 1999. Microbial diversity in marine sediments from Sagami Bay and Tokyo Bay, Japan, as determined by 16S rRNA gene analysis. Microbiology 145:3305-3315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vetriani, C., H. W. Jannasch, B. J. MacGregor, D. A. Stahl, and A. L. Reysenbach. 1999. Population structure and phylogenetic characterization of marine benthic Archaea in deep-sea sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:4375-4384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vetriani, C., A. L. Reysenbach, and J. Dore. 1998. Recovery and phylogenetic analysis of archaeal rRNA sequences from continental shelf sediments. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 161:83-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.von Wintzingerode, F., U. B. Göbel, and E. Stackebrandt. 1997. Determination of microbial diversity in environmental samples: pitfalls of PCR-based rRNA analysis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 21:213-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xiao, C., P. Zhou, and D. Wang. 1990. Identification and growth temperature characteristics of psychrophiles from Antarctic sediments. Acta Microbiol. Sin. 30:239-242. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zehr, J. P., and M. Voytek. 1999. Molecular ecology of aquatic communities: reflections and future directions. Hydrobiologia 401:1-8. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zwart, G., W. D. Hiorns, B. A. Methe, M. P. Van Agterveld, R. Huismans, S. C. Nold, J. P. Zehr, and H. J. Laanbroek. 1998. Nearly identical 16S rRNA sequences recovered from lakes in North America and Europe indicate the existence of clades of globally distributed freshwater bacteria. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 21:546-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]