Abstract

Rhodococcus (opacus) erythropolis HL PM-1 grows on 2,4,6-trinitrophenol or 2,4-dinitrophenol (2,4-DNP) as a sole nitrogen source. The NADPH-dependent F420 reductase (NDFR; encoded by npdG) and the hydride transferase II (HTII; encoded by npdI) of the strain were previously shown to convert both nitrophenols to their respective hydride Meisenheimer complexes. In the present study, npdG and npdI were amplified from six 2,4-DNP degrading Rhodococcus spp. The genes showed sequence similarities of 86 to 99% to the respective npd genes of strain HL PM-1. Heterologous expression of the npdG and npdI genes showed that they were involved in 2,4-DNP degradation. Sequence analyses of both the NDFRs and the HTIIs revealed conserved domains which may be involved in binding of NADPH or F420. Phylogenetic analyses of the NDFRs showed that they represent a new group in the family of F420-dependent NADPH reductases. Phylogenetic analyses of the HTIIs revealed that they form an additional group in the family of F420-dependent glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenases and F420-dependent N5,N10-methylenetetrahydromethanopterin reductases. Thus, the NDFRs and the HTIIs may each represent a novel group of F420-dependent enzymes involved in catabolism.

Toxic polynitroaromatics such as 2,4,6-trinitrophenol (picric acid [PA]) and 2,4-dinitrophenol (2,4-DNP) contaminate the environment and industrial effluents. These compounds have been extensively used in the chemical industry for the synthesis of dyes, pesticides, and explosives in the past. Several bacteria have the capacity to use these nitroaromatics as nitrogen or carbon sources (3, 5, 14, 15, 18, 29). Rhodococcus (opacus) erythropolis HL PM-1 was originally isolated by its ability to grow on 2,4-DNP as sole nitrogen source (23).

PA or 2,4-DNP degradation occurs by initial reduction (hydrogenation) of the aromatic ring, producing the respective hydride and dihydride Meisenheimer complexes of PA (H−-PA and 2H−-PA) or 2,4-DNP (H−-2,4-DNP). The PA-degrading bacterium R. (opacus) erythropolis HL PM-1 possesses a npd gene cluster, containing npdC (encoding hydride transferase I [HTI]), npdG (encoding the NADPH-dependent F420 reductase [NDFR]), and npdI (encoding HTII) (9, 17, 30). HTII performs the first hydride transfer to PA, forming H−-PA, and HTI catalyzes the second hydride transfer, giving rise to 2H−-PA. Both enzymes require the NDFR to supply the hydride ions in the form of F420H2.

We have found here homologous genes for npdG and npdI in several 2,4-DNP-degrading strains of the genus Rhodococcus. Further, it was shown that the npdG and npdI genes have the same function as the homologous genes in R. (opacus) erythropolis HL PM-1. Hence, they are involved in the degradation of 2,4-DNP. We have also detected these genes in Rhodococcus sp. strain PN1, which was originally enriched on p-nitrophenol (4NP). The strain degrades 4NP by an oxygenolytic pathway via 4-nitrocatechol, which has nothing in common with the 2,4-DNP pathway (33). Several bacteria are known to degrade 4NP by oxygenolytic removal of the nitro group, producing hydroquinone or via 4-nitrocatechol into 1,2,4-benzenetriol (20, 25, 26, 32).

We propose that the NDFRs form a new group within the family of F420-dependent NADPH reductases (FDNRs). Similarly, we suggest that the HTIIs form a new group within a protein family, which we refer to here as the F420-dependent glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenases-F420-dependent N5,N10-methylenetetrahydromethanopterin reductases-hydride transferases (FGD-MER-HT).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria, culture conditions, and plasmids.

The bacterial strains used are listed in Table 1. The plasmids used are listed in Table 2. Escherichia coli strains were cultured at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium. Ampicillin (100 μg/ml) or kanamycin (80 μg/ml) was added for the maintenance of plasmids. For gene expression, overnight cultures of E. coli BL21(DE3)(pNTG29) or E. coli JM109(pQEG1) were induced with IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) as described previously (17). Rhodococcus strains were cultured at 30°C in LB medium or in 50 mM KH2PO4-Na2HPO4 buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.45 mM CaCl2, 50 mM acetate, and modified mineral salts solution (8). The salts solution contained 0.3 to 0.5 mM 2,4-DNP as a nitrogen source.

TABLE 1.

Bacteria used in this study

| Bacterial strain | Relevant genotype and/or phenotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli JM109 | endA1 recA1 gyrA96 thi hsdR17 (rK− mK+) relA1 supE44 λ−Δ(lac-proAB) (F′ traD36 proAB laqIqZΔM15) λ− | 38 |

| E. coli DH5α | deoR endA1 gyrA96 hsdR17 (rK− mK+) recA1 relA1 supE44 thi-1 Δ(lacZYA-argFV169) φ80δlacZΔM15 F− λ− | Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif. |

| E. coli BL21 (DE3) | F−ompT hsdS(rB− mB−) gal (λcIts857 ind1 Sam7 nin5 lacUV5-T7 gene1 | Calbiochem-Novabiochem, San Diego, Calif. |

| R. (opacus) erythropolis HL PM-1 | Ability to grow on PA and 2,4-DNP as sole nitrogen source | 23 |

| R. erythropolis HL 24-1 | Ability to grow on 2,4-DNP as sole nitrogen source | 24 |

| Rhodococcus sp. strain RB1 | Ability to grow on 2,4-DNP as sole nitrogen source | 5 |

| Rhodococcus sp. strain CB 24-1 | Ability to grow on 2,4-DNP as sole nitrogen source | 6 |

| Rhodococcus sp. strain DNP 14-5 | Ability to grow on 2,4-DNP as sole nitrogen source | Michael Bramucci, Dupont Life Sciences, Wilmington, Del. |

| Rhodococcus sp. strain DNP 14-9 | Ability to grow on 2,4-DNP as sole nitrogen source | Michael Bramucci, Dupont Life Sciences, Wilmington, Del. |

| Rhodococcus sp. strain PN1 | Ability to grow on 2,4-DNP and 4NP as sole nitrogen source | 34 |

| R. rhodochrous ATCC 12674 | Inability to grow on PA or 2,4-DNP as sole nitrogen source | 7 |

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Relevant genotypea | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| pBluescript SK II(+) | Apr; Plac; ColE1 ori | Gibco-BRL |

| pAC28 | Kmr; phage T7 promoter; ColE1 ori; C-terminal tag containing six polyhistidine | 21 |

| pUC18 | Apr; Plac; ColE1 ori | Gibco-BRL |

| pQE-80L | Apr; phase T5 promoter ColE1 ori; N-terminal tag containing six polyhistidines | Qiagen |

| pK4 | Kmr; Plac; ColE1 ori; Rhodococcus ori | 16 |

| pNTG29 | npdG of strain CB 24-1 in NdeI and BamHI site of pAC28 | This study |

| pNTG31 | npdG of strain HL 24-1 in NdeI and BamHI site of pAC28 | This study |

| pNTG32 | npdG of strain DNP 14-5 in NdeI and BamHI site of pAC28 | This study |

| pQEG1 | npdG of strain PN1 in BamHI and KpnI site of pQE-80L | This study |

| pKCB2 | npdG and npdI of strain CB 24-1 in PstI site of pK4 | This study |

| pKHL1 | npdG and npdI of strain HL 24-1 in PstI site of pK4 | This study |

| pKDNP1 | npdG and npdI of strain DNP 14-5 in PstI site of pK4 | This study |

| pKPNGI1 | npdG and npdI of strain PN1 in KpnI site of pK4 | This study |

Apr, ampicillin resistance; Kmr, kanamycin resistance.

Purification, manipulation, and transformation of DNA.

Plasmid DNA from E. coli was isolated by using Qiagen columns (Qiagen GmbH). Genomic DNA was purified according to Eulberg et al. (11). DNA fragments were purified from agarose gels by using the Easypure DNA purification kit (Biozym Diagnostics GmbH, Hess-Oldendorf, Germany). DNA manipulations were accomplished by using standard methods (2, 24, 31). E. coli was transformed with plasmid DNA according to Inoue et al. (19). Electroporation of R. rhodochrous ATCC 12674 was performed according to the method of Hashimoto et al. (16). The conditions were as follows: 1-mm electrode gap electroporation cuvettes, a voltage of 1.8 to 2 kV, a capacity of 25 μF, a resistance of 400 Ω, and a time constant of 6.8 to 9.5 ms.

Amplification and cloning of DNA.

PCR was performed in a T Gradient Thermocycler 96 (Biometra GmbH, Göttingen, Germany). Primers were purchased from MWG Biotech AG (Ebersberg, Germany). Reaction mixtures (total volume of 25 μl) contained 50 pmol of each primer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 4% dimethyl sulfoxide, 0.2 mM of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 0.5 U of Taq polymerase (Gibco/Life Technologies GmbH), 1× PCR buffer (Gibco/Life Technologies GmbH), and 10 to 100 ng of genomic or plasmid DNA. The cycling parameters were as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min, followed by 20 cycles consisting of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 55 to 64°C for 30 s, and elongation at 72°C for 2 min.

The primers used for amplification of the npdG genes from the Rhodococcus strains RB1, PN1, HL 24-1, CB 24-1, DNP 14-5, and DNP 14-9 were 5′-ATG AAG TC(GC) TC(GC) AAG ATC GC(GC) GTC-3′, 5′-ATG AAG AGC AGC AAG ATC GC(GC) GTC-3′, or 5′-CGC (AC)GC (CT)CG CGG ATC GTG (AG)AC-3′. npdI genes were amplified with the primers 5′-ATG ATC AA(AG) GGC ATC CAG CT(GC) CA(CT) GG-3′ and 5′-(GCT)GC (GC)AG CTC CGG (GC)AG GAC CTG-3′.

To produce a His-Tag fusion protein of the npdG genes from strains CB 24-1, HL 24-1, and DNP 14-5, the primers used were 5′-TTT TCA TAT GAA GAG CAG CAA GAT CGC-3′ and 5′-TTT TGG ATC CTC AGG CGG CGC GTG GGT C-3′ (NdeI and BamHI restriction sites are underlined). The PCR products were restricted with NdeI and BamHI and ligated into the NdeI and BamHI sites of pAC28.

To produce a His-Tag fusion protein of the npdG gene from strain PN1, the primers employed were 5′-GAGGGATCCTTGAAGAGCAGCAAGATTGCC-3′ and 5′-GGTGGTACCCTCGGCACGGCCCGGCAGAGCACGG-3′ (BamHI and KpnI sites are underlined). The PCR product was restricted with BamHI and KpnI and ligated into the BamHI and the KpnI site of pQE-80L.

For expression of npdG and npdI of strain CB 24-1 in R. rhodochrous ATCC 12674, npdG was amplified with the primers 5′-TTT TCT GCA GAT GAA GAG CAG CAA GAT CGC-3′ and 5′-TTT TGG ATC CTC AGG CGG CGC GTG GGT C-3′), and npdI was amplified with the primers 5′-TTT TGG ATC CGT CGC CGT GTT CTG CCC TTA AC-3′ and 5′-TTT TCT GCA GTC AGG CGA GCT CCG GGA C-3′ (the PstI and BamHI sites are underlined). The PCR products were digested with BamHI and subsequently ligated to produce a single PstI fragment with npdG and npdI juxtaposed to one another. The PstI fragment was finally restricted with PstI and ligated into the PstI site of pK4.

For expression of npdG and npdI of strain PN1 in R. rhodochrous ATCC 12674, npdG or npdI were amplified with the primers 5′-TCGGGTACCTCCCGTCCCAACGT GTAGGAGACAG-3′ and 5′-GGTGGTACCCTCGGCACGGCCCGGCAGAGCACGG-3′ for npdG and the primers 5′-TATGGTACCTCGAGTTCAACATCATGAAGAGAAGTC-3′ and 5′-TTCGGTACCGCACAGGTCCCGCGTTGCCTGCGTG-3′ for npdI (the KpnI sites are underlined). The products were cut with KpnI and inserted together into the KpnI site of pK4.

For expression of npdG and npdI from Rhodococcus sp. strain HL 24-1, the primers used for amplification were 5′-TCATGCGAGCTCCGGCAGGACCTGG-3′ and 5′-ATGAAGAGCAGCAAGATCGCCGTCGTC-3′. For expression of npdG and npdI from Rhodococcus sp. strain DNP 14-5, the primers used for amplification were 5′-CCCAAGCTTGGGTCATGCGAGCTCCGGCAGGAC-3′ and 5′-TTTTCTGCAGATGAAGAGCAGCAAGATCGC-3′. The PCR fragments were ligated into the PstI site of pK4, which had been cut with PstI and blunt ends created with T4 DNA polymerase (MBI Fermentas).

Sequence and phylogenetic analyses.

Sequencing was performed commercially (MWG Biotech AG). Homology searches were performed with BLASTN, BLASTP, and BLASTX. Motif searches were performed with the Motif tool (http://motif.genome.ad.jp). Pairwise and multiple alignments were carried out by using BLAST2 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gorf/bl2.html) and CLUSTALW (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw/[1, 35, 36]). Translations were achieved by using the Translation Machine (http://www2.ebi.ac.uk/; EMBL Outstation European Bioinformatics Institute). Phylogenetic trees were constructed by using PROML (maximum likelihood), SEQBOOT, CONSENSE, and DRAWTREE of PHYLIP 3.6a (12).

Enzyme purification, enzyme assays, and SDS-PAGE.

NDFRs and HTIIs were purified as His-Tag fusion proteins as previously described (17). Preparation of cell extracts, determination of protein concentrations, and sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) were done as previously described. Reduction of F420 to F420H2 by the purified NDFR was monitored by using the method previously described. The concentration of F420 was 10 to 21.4 μM. The amount of pure protein added was 0.25 to 0.7 μg. The reaction time was 12 s. Conversion of PA to the hydride Meisenheimer complex of PA was performed as described earlier.

Resting-cell experiments.

Cells (exponential phase) were resuspended in 50 mM KH2PO4-K2HPO4 buffer (pH 7.5) to obtain an optical density at 595 nm (OD595) of 2.0. PA or 2,4-DNP were added to a final concentration of 0.5 or 0.7 mM. Cell suspensions were shaken at 30°C, and culture supernatants were analyzed by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) at regular time intervals.

HPLC analyses.

Metabolites were detected and analyzed as previously described (17).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences have been submitted to GenBank. The accession numbers are AY027571, AY027572, AY027573, AY027574, are AY027575 for the npdG genes and AY027566, AY027567, AY027568, AY027569, and AY027570 for the npdI genes. The accession number for the genes from strain PN1 is AB090357.

RESULTS

Growth of Rhodococcus strains on 2,4-DNP.

To test the 2,4-DNP-degrading capacity, bacteria were cultured in minimal media with 2,4-DNP as the sole nitrogen source and acetate as the sole carbon source. Growth was detected by an increase in the OD595 with a concomitant decolorization of 2,4-DNP. HPLC analysis showed the disappearance of 2,4-DNP in the culture medium. There was no increase in OD595 in the absence of 2,4-DNP. This indicated that all of the strains examined grew on 2,4-DNP as a sole nitrogen source.

The npdG or npdI gene sequences show high sequence similarities to one another.

Pairwise alignments performed with the npdG and npdI genes from the Rhodococcus spp. (Table 1) and npdG and npdI from the reference strain R. (opacus) erythropolis HL PM-1 showed high sequence identities (86 to 99%), suggesting that the genes are homologous. The npd genes of Rhodococcus sp. strain RB1 showed the highest sequence identities (99%), and the npd genes of Rhodococcus sp. strains CB 24-1 and HL 24-1 had the lowest sequence identities (86%). The sequences of strains DNP 14-5 and DNP 14-9 were identical to one another.

The npdG genes are involved in the conversion of F420 to F420H2.

In order to prove the involvement of the npdG genes in 2,4-DNP degradation, we cloned the genes from strains CB 24-1, PN1, HL 24-1, and DNP 14-5. npdG was amplified from strains CB 24-1, HL 24-1, or DNP 14-5 and cloned into pAC28 to produce pNTG29, pNTG31, or pNTG32, respectively. The genes were expressed as His-Tag fusion proteins in E. coli BL21(DE3) containing the respective plasmids. npdG was amplified from strain PN1 and cloned into pQE-80L to produce pQEG1. The gene was expressed as a His-Tag fusion protein in E. coli JM109(pQEG1). Cell extracts were prepared from induced cultures, and the proteins purified to 95% homogeneity. All of the NDFRs converted F420 to F420H2. Hence, we may surmise that the npdG genes are involved in the degradation of 2,4-DNP.

The specific activity was determined for the NDFRs from strains CB 24-1 and PN1. NDFR from strain CB 24-1 converted F420 to F420H2 with a specific activity of 23.5 ± 2 U/mg. This was comparable to the activity of NDFR from strain HL PM-1 (17). The NDFR from strain PN1 had an activity of 57.3 ± 0.6 U/mg for F420. This was about 2.5 times higher than the activity of NDFR from strains CB 24-1 or HL PM-1. This may be a reflection of the differences in sequence.

The npdI genes encode hydride transferases (HTs) involved in the initial hydride transfer.

Our aim was to prove the role of the npdI genes in 2,4-DNP degradation. According to Ebert et al. (9) and Heiss et al. (17), HTII requires NDFR for converting 2,4-DNP to the H−-2,4-DNP or PA to the H−-PA. Hence, npdI and npdG were cloned from Rhodococcus spp. CB 24-1, DNP 14-5, HL 24-1, or PN1 into pK4 to create pKCB2, pKDNP1, pKHLI, or pKPNGI1, respectively. The plasmids were transformed into R. rhodochrous ATCC 12674 to create R. rhodochrous ATCC 12674(pKCB2), R. rhodochrous ATCC 12674(pKDNP1), R. rhodochrous ATCC 12674(pKHLI), and R. rhodochrous ATCC 12674(pKPNGI1).

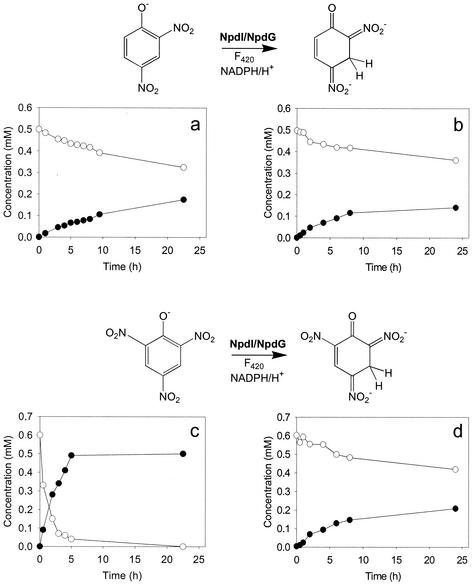

Resting cells of R. rhodochrous ATCC 12674(pKCB2), R. rhodochrous ATCC 12674(pKPNGI1) (Fig. 1), R. rhodochrous ATCC 12674(pKDNP1), and R. rhodochrous ATCC 12674(pKHLI) (data not shown) converted 2,4-DNP to the hydride Meisenheimer complex of 2,4-DNP (H−-2,4-DNP). They also converted PA to the hydride Meisenheimer complex of PA (H−-PA), indicating the transfer of a hydride ion to the aromatic ring of PA or 2,4-DNP. Both the spectra and the retention volumes of the products were identical to the authentic Meisenheimer complexes described above. This finding shows that the HTIIs are involved in the hydride transfer to 2,4-DNP or PA and that the npdI genes are involved in the degradation of 2,4-DNP.

FIG. 1.

Conversion of 2,4-DNP (○) to the H−-2,4-DNP (•) by resting cells of R. rhodochrous ATCC 12674(pKCB2) (a) or R. rhodochrous ATCC 12674(pKPNGI1) (b) and conversion of PA (○) to the H−-PA (•) by resting cells of R. rhodochrous ATCC 12674(pKCB2) (c) or R. rhodochrous ATCC 12674(pKPNGI1) (d). Cells were grown in LB medium plus kanamycin. Cells were harvested in the exponential growth phase, washed, and resuspended in 50 mM KH2PO4-K2HPO4 buffer (pH 7.5) to obtain an OD595 of 2.0. 2,4-DNP or PA was added to a final concentration of 0.5 or 0.6 mM. Cell suspensions were shaken at 30°C, and culture supernatants analyzed by HPLC at regular time intervals.

Notably, resting cells of R. rhodochrous ATCC 12674(pKCB2) almost completely converted PA to the H−-PA within 25 min, whereas 2,4-DNP was not completely converted to the H−-2,4-DNP under the same conditions. Resting cells of R. rhodochrous ATCC 12674(pKPNGI1) did not convert either compound completely within the time frame measured.

R. rhodochrous ATCC 12674(pK4) did not convert either PA or 2,4-DNP. Further, cell extracts prepared from strain R. rhodochrous ATCC 12674 showed no NDFR activity. To show that the strain does not possess a functional HTII, an enzyme assay was performed with PA as a substrate, cell extracts from strain ATCC 12674, and purified NDFR [from R. (opacus) erythropolis HL PM-1]. PA was not converted. This shows that strain ATCC 12674 does not possess a functional NDFR or HTII.

The NDFRs (NpdGs) form a new protein group.

BLASTX searches performed with the npdG genes detected similarities with FDNRs or oxidoreducates from Streptomyces spp., Nocardioides simplex FJ2-1A, and Archaea strains. The NDFRs had the highest sequence similarities with the NADPH-dependent F420 reductase of N. simplex FJ2-1A (similarity, 65 to 68%; identity, 57 to 58%; expect value, 9e−62; score 237).

Multiple alignments revealed five conserved domains across the entire length of the proteins. The consensus sequences of the most highly conserved domains were as follows: (i) [I,L,V][A,G][I,F,V,L][L,I,V]GGTGX(2)GXG[L,M][A,V]X(2)[A,G]X(2)[G,N] at positions 6 to 27 of NpdG of strain HL PM-1; (ii) [V,I][V,I][V,I,L]GSRX(2)EXAX(3)A at positions 30 to 44; (iii) [V,I,L]X[G,A]X(2)NX(3)[A,V]X(4)[V,I]X[V,I,L,F][V,I,L,F]X[VIL] at positions 57 to 76; (iv) GS[A,V][A,T]X(13)V[AV][A,G,S]A at positions 119 to 137; and (v) DX(2)[V,I]X[G,S][E,D,N]X(7)[V,A]X(2)L[A,T]X(2)[I,V,M]X(5)[V,I,L]X(2)GX[L,V]X(2)[A,S]X(2)[V,L,I,M]EX[L,I][V,T][A,P]X[L,I][L,I][S,G,N][V,L] at positions 155 to 204.

Several motifs were detected across the NpdG sequence from the Blocks database. Three signatures were identified in the first conserved domain (positions 5 to 28): (i) an aromatic-ring hydroxylase (flavoprotein monooxygenase) signature (score 1003), (ii) an isoflavone reductase signature (score 1195), and (iii) an NAD-dependent epimerase/dehydratase family signature (score 1082). All three of these enzyme families require NAD(P)H or FAD as cofactors. Interestingly, this consensus region is glycine-rich.

Further signatures were detected at positions 56 to 80 (conserved region number 3). These included a signature of the aspartate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase protein family (score 1040) and a GTP-binding domain (score 1029). Both protein families possess NADP- or GTP-binding domains, respectively. Lastly, an oxidoreductase FAD and NAD(P)-binding domain at positions 156 to 167 were found. This motif was contained within the fifth conserved region identified from the multiple alignment. Since all of the motifs were contained in NAD(P)- or flavin-binding proteins, the conserved regions may be required for binding of NAD(P)H or F420.

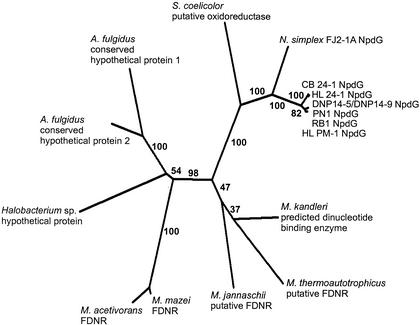

A phylogenetic tree showed that the NDFRs from the Rhodococcus spp. clustered as a separate group from the FDNRs (Fig. 2). For simplicity, we propose to collectively call the NDFRs and FDNRs the F420-NADP-oxidoreductases.

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic tree showing the phylogenetic interrelationships of the NDFRs with the FDNRs. The protein sequences were aligned by using CLUSTALW. The tree was calculated by using maximum likelihood (PROML) of the program PHYLIP 3.6a. Bootstrap analyses were performed with SEQBOOT and CONSENSE, and the tree was drawn with DRAWTREE of the program PHYLIP 3.6a. Numbers on the branches indicate the frequency (out of 100 data sets) with which the branch occurred during bootstrap analysis. S. coelicolor, Streptomyces coelicolor (T50571); N. simplex FJ2-1A NpdG, Nocardioides simplex FJ2-1A NDFR (AAK38741); CB 24-1 NpdG, Rhodococcus sp. strain CB 24-1 NDFR; HL 24-1 NpdG, Rhodococcus sp. strain HL 24-1 NDFR; DNP 14-5 and DNP 14-9 NpdG, Rhodococcus sp. strain DNP 14-5 NDFR and Rhodococcus sp. strain DNP 14-9 NDFR; PN1 NpdG, Rhodococcus sp. strain PN1 NDFR; RB1 NpdG, Rhodococcus sp. strain RB1 NDFR; HL PM-1 NpdG, R. (opacus) erythropolis NDFR; M. kandleri, Methanopyrus kandleri (AAM01450); M. thermoautotrophicus, Methanothermobacter thermoautotrophicus FDNR (O26350); M. jannaschii, Methanococcus jannaschii FDNR (Q58896); M. mazei, Methanosarcina mazei FDNR (AAM30673); M. acetivorans, Methanosarcina acetivorans FDNR (AAM07580); Halobacterium sp., (AAG20646); A. fulgidus conserved hypothetical protein 1, Archaeoglobus fulgidus (AAB90038); A. fulgidus conserved hypothetical protein 2, Archaeoglobus fulgidus (AAB90348).

The HTIIs (NpdIs) form a new protein group.

Homology searches performed with the npdI genes identified N5,N10-methylenetetrahydromethanopterin reductases (MERs) from Archaea, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenases (FGDs) from Mycobacterium, and an HT from N. simplex FJ2-1A. The HTIIs had the highest sequence similarities with the latter (similarity, 65 to 77%; identity, 55 to 67%; expect value, 6e−130; score 464; AAK38742). As for the FDNRs, all of these enzymes were dependent on the coenzyme F420 or flavins.

Multiple alignments with the HTIIs, the HTI (from strain HL PM-1), the MERs, and FGDs revealed four conserved domains, particularly in the NH2-terminal two-thirds of the proteins. The FGD-MER-HT consensus sequences were very similar to the FGD-MER consensus sequences previously identified by Purwantini et al. (28). They were as follows: (i) AX(4)[F,M][D,E]X(3)[M,V,I,L][T,S]D[H,Q] at positions 23 to 35 of NpdI of strain HL PM-1; (ii) TX(4)[L,V]G[T,P][A,G,S]X(13)A[S,Q,K][T,A,S][M,I,F,L]X[S,T][I,L,M]X(2)[M,I,F,L]X(6)[V,L]X[M,I,L,V]GXG at positions 52 to 93; (iii) EX[V,I]X(3)RX[M,L,F]X(3)[D,E,K]X[V,I]X(3)[G,D]X(9)[M,I,L] at positions 114 to 142; (iv) [I,V]X[I,V]X[F,I,M,V)[A,G][A,G]X[S,G][T,P]X(3)[R,K,E,Q]X(2)[A,G]X(2)[G,A,S]DG at positions 158 to 179.

Motif searches identified the following signature sequences at positions 159 to 181 (conserved region number 4) from the Blocks and Prints databases: aromatic ring hydroxylase (flavoprotein mononoxygenase) (score 1146), FAD-dependent pyridine nucleotide reductase (score 1047), NAD/NADP octopine/nopaline dehydrogenase (score: 1049), and flavin-containing amine oxidase (score 1006). This region may be significant for binding of NAD(P), flavins, or F420.

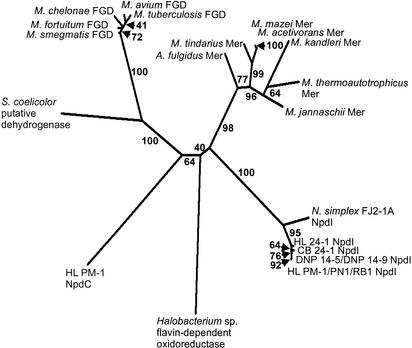

A phylogenetic tree calculated from the HTII, FGD, and the MER sequences showed that the HTIIs and the HT of N. simplex FJ2-1A constituted a new group separate from the FGDs, the MERs, and the HTI of R. (opacus) erythropolis HL PM-1 (Fig. 3). Because of the similarity of the HTIIs with the HT of N. simplex FJ2-1A, we propose to call of the HT of N. simplex FJ2-1A, HTII (NpdI).

FIG. 3.

Phylogenetic tree showing the phylogenetic interrelationships of the HTs with the MERs and the FGDs. See Fig. 2 for details of the analysis. N. simplex FJ2-1A NpdI, Nocardioides simplex FJ2-1A HTII (AAK38742); HL 24-1 NpdI, Rhodococcus sp. strain HL 24-1 HTII; CB 24-1 NpdI, Rhodococcus sp. strain CB 24-1 HTII; DNP 14-5 and DNP 14-9 NpdI, Rhodococcus sp. strain DNP 14-5 HTII and Rhodococcus sp. strain DNP 14-9 HTII; HL PM-1/PN1/RB1 NpdI, R. (opacus) erythropolis HL PM-1 HTII (AF323606), Rhodococcus sp. strain PN1 HTII and Rhodococcus sp. strain RB1 HTII; Halobacterium sp. (no. 16554492); HL PM-1 NpdC, R. (opacus) erythropolis HL PM-1 HTI (AF323606); S. coelicolor, Streptomyces coelicolor (T34725); M. smegmatis, Mycobacterium smegmatis FGD (AAC38338); M. fortuitum, Mycobacterium fortuitum FGD (T44605); M. chelonae, Mycobacterium chelonae FGD (AAD38167); M. avium, Mycobacterium avium FGD (AAD38165); M. tuberculosis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis FGD (AAK44644); A. fulgidus: Archaeoglobus fulgidus Mer (B69383); M. tindarius, Methanolobus tindarius Mer (T45226); M. mazei, Methanosarcina mazei Mer (AAM30324); M. acetivorans, Methanosarcina acetivorans Mer (AAM07085); M. kandleri, Methanopyrus kandleri Mer (AAM01739); M. thermoautotrophicum, Methanothermobacter thermoautotrophicum Mer (AAB86222); M. jannaschii, Methanococcus jannaschii Mer (AAB99555).

DISCUSSION

The majority of the bacteria known up to date with the ability to mineralize 2,4-DNP or PA by initial reduction of the aromatic ring are gram-positive actinomycetes (3, 5, 9, 23, 29). In contrast, gram-negative bacteria do not seem to possess productive 2,4-DNP degradation capabilities (13, 18, 14). The present study has shown that six Rhodococcus spp. all have the capacity to grow on 2,4-DNP as sole nitrogen source and contain homologous enzymes (NDFR and HTII) involved in the initial reductive attack on 2,4-DNP or PA. It is interesting that Rhodococcus sp. strain PN1, which was initially enriched on 4NP (33), also possesses the ring hydrogenation capacity of 2,4-DNP and the responsible npdG and npdI genes. In contrast, the 2,4-DNP degraders HL PM-1 and HL 24-1 do not grow on 4NP or other mononitrophenols (22).

Homology searches with both the NDFRs and the HTIIs identified F420-dependent enzymes (FDNRs, MERs, and FGDs) from Archaea or actinomycetes. No homologous enzymes from gram-negative bacteria were detected. This coincides with the absence of the coenzyme F420 in these bacteria. Hence, gram-negative bacteria may lack the ability to reduce the aromatic nuclei of 2,4-DNP or PA because they lack the HTs and the coenzyme F420 for it.

Functionally, F420-dependent oxidoreductases shuttle electrons between F420 and NADPH and have primarily been shown to play a role in methanogenesis in Archaea. The MERs in Archaea also play a role in methanogenesis (4). FGDs convert glucose-6-phosphate to 6-phosphogluconolactone in the presence of F420 and have been detected in the actinomycetes Streptomyces, Corynebacterium, and Mycobacterium (10, 27). That F420-dependent enzymes play a role in degradation of nitroaromatic compounds was demonstrated for the first time in N. simplex FJ2-1A, and R. (opacus) erythropolis HL PM-1 (9, 30). In the present work, homologous HTIIs and NDFRs were detected in several closely related Rhodococcus spp. and shown to play a role in 2,4-DNP or PA hydrogenation.

Consensus sequences were identified in the NDFRs and the FDNRs. The FGD-MER-HT consensus regions were comparable to the FGD-MER consensus sequences described previously (28). The authors of that study proposed that these regions may be involved in the binding of F420. Hence, the conserved domains may reveal structurally important motifs and should assist in future predictions on potential regions involved in the binding of coenzymes.

The phylogenetic analyses showed that the NDFRs form a new group within the group of FDNRs (Fig. 2). Similarly, the HTIIs formed a new group within the MERs and FGDs (Fig. 3). The FGD-MER-HT tree shows different groups of proteins with differing functions derived from different phylogenetic groups of microorganisms: the FGDs from mycobacteria, the MERs from the Archaea and the HTIIs from the 2,4-DNP degrading Rhodococcus spp. The three protein groups may have originated from a common ancestor, followed by independent evolution in each taxon subsequent to lateral gene transfer.

The HTI from strain HL PM-1 was shown to be involved in the hydride transfer to H−-PA to form 2H−-PA (17). The phylogenetic tree showed that this enzyme did not cluster with the HTIIs. However, the FGD-MER-HT consensus sequences were also found in the HTI. This coincides with the enzymes' similar functions: both the HTII and the HTI are involved in hydride transfer reactions, and both require F420H2. Only their substrate specificities differ: the HTII takes PA, whereas the HTI takes only the hydride Meisenheimer complexes (H−-PA or the H−-2,4-DNP) as its substrates.

The npdG and npdI gene showed very high sequence similarities and clustered separately from related enzymes. Hence, they may be suitable for use as gene probes for finding bacteria in the environment with the capacity to hydrogenate electron deficient aromatic ring systems. Further, the ability to assess the maintenance of a PA-degrading population in continuous culture is important for efficient bioelimination of PA from industrial effluents. We plan to examine more 2,4-DNP/PA utilizers (and bacteria lacking this ability) for the presence of npdG, npdI, and npdC for a statistically significant sample to confirm that the genes are specific to 2,4-DNP or PA degraders.

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the technical assistance of A. Richter. We are grateful to V. Nagarajan and M. Bramucci (Dupont, Wilmington, Del.) for providing strains DNP 14-5 and DNP 14-9, R. Blasco (Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Cordoba, Cordoba, Spain) for R. opacus RB1, F. Yu (Chemicals Development Laboratories, Mitsubishi Rayon Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) for pK4, and N. Kholod (La Jolla Cancer Research Center, La Jolla, Calif.) for pAC28. We also thank L. Daniels (Department of Microbiology, University of Iowa, Iowa City) for the coenzyme F420.

This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the Hyogo Prefecture Government.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 2001. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 3.Behrend, C., and K. Heesche-Wagner. 1999. Formation of hydride-Meisenheimer complexes of picric acid (2,4,6-trinitrophenol) and 2,4-dinitrophenol during mineralization of picric acid by Nocardioides sp. strain CB 22-2. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1372-1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berk, H., and R. K. Thauer. 1997. Function of coenzyme F420-dependent NADP reductase in methanogenic Archaea containing an NADP-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase. Arch. Microbiol. 168:396-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blasco, R., E. Moore, V. Wray, D. Pieper, K. Timmis, and F. Castillo. 1999. 3-Nitroadipate, a metabolic intermediate for mineralization of 2,4-dinitrophenol by a new strain of a Rhodococcus species. J. Bacteriol. 181:149-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruhn, C., H. Lenke, and H.-J. Knackmuss. 1987. Nitrosubstituted aromatic compounds as nitrogen source for bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 53:208-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dabbs, E. R., and G. J. Sole. 1988. Plasmid-borne resistance to arsenate, arsenite, cadmium, and chloramphenicol in a Rhodococcus species. Mol. Gen. Genet. 211:148-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorn, E., M. Hellwig, W. Reineke, and H.-J. Knackmuss. 1974. Isolation and characterization of a 3-chlorobenzoate degrading pseudomonad. Arch. Microbiol. 99:61-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ebert, S., P. G. Rieger, and H.-J. Knackmuss. 1999. Function of coenzyme F420 in aerobic catabolism of 2,4,6-trinitrophenol and 2,4-dinitrophenol by Nocardioides simplex FJ2-1A. J. Bacteriol. 181:2669-2674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eker, A. P., J. K. Hessels, and R. Meerwaldt. 1989. Characterization of an 8-hydroxy-5-deazaflavin:NADPH oxidoreductase from Streptomyces griseus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 990:80-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eulberg, D., L. A. Golovleva, and M. Schlömann. 1997. Characterization of catechol catabolic genes from Rhodococcus erythropolis 1CP. J. Bacteriol. 179:370-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Felsenstein, J. 1989. PHYLIP: phylogeny inference package (version 3.2). Cladistics 5:164-166. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gisi, D., G. Stucki, K. W. Hanselmann. 1997. Biodegradation of the pesticide 4,6-dinitro-ortho-cresol by microorganisms in batch cultures and in fixed-bed column reactors. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 48:441-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gorontzy, T., J. Kuver, and K.-H. Blotevogel. 1993. Microbial transformation of nitroaromatic compounds under anaerobic conditions. J. Gen. Microbiol. 139:1331-1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanne, L. F., L. L. Kirk, S. M. Appel, A. D. Narayan, K. K. Bains. 1993. Degradation and induction specificity in actinomycetes that degrade p-nitrophenol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:3505-3508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hashimoto, Y., M. Nishiyama, F. Yu, I. Watanabe, S. Horinouchi, and T. Beppu. 1992. Development of a host-vector system in a Rhodococcus strain and its use for expression of the cloned nitrile hydratase gene cluster. J. Gen. Microbiol. 138:1003-1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heiss, G., K. W. Hofmann, N. Trachtmann, D. M. Walters, P. Rouvière, and H.-J. Knackmuss. 2002. npd gene functions of Rhodococcus (opacus) erythropolis HL PM-1 in the initial steps of 2,4,6-trinitrophenol degradation. Microbiology 148:799-806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hess, T. F., S. K. Schmidt, J. Silverstein, and B. Howe. 1990. Supplemental substrate enhancement of 2,4-DNP mineralization by a bacterial consortium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:1551-1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inoue, H., H. Nojima, and H. Okayama. 1990. High efficiency transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. Gene 96:23-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jain, R. K., J. H. Dreisbach, and J. C. Spain. 1994. Biodegradation of p-nitrophenol via 1,2,4-benzentriol by an Arthrobacter sp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:3030-3032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kholod, N., and T, Mustelin. 2001. Novel vectors for co-expression of two proteins in E. coli. BioTechniques 31:322-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lenke, H. 1990. Mikrobieller Abbau von Nitrophenolen: 2,4-Dinitrophenole und 2,4,6-Trinitrophenol. Ph.D. dissertation. University of Stuttgart, Stuttgart, Germany.

- 23.Lenke, H., and H.-J. Knackmuss. 1992. Initial hydrogenation during catabolism of picric acid by Rhodococcus erythropolis HL 24-2. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:2933-2937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lenke, H., D. H. Pieper, C. Bruhn, and H.-J. Knackmuss. 1992. Degradation of 2,4-dinitrophenol by two Rhodococcus erythropolis strains, HL 24-1 and HL 24-2. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:2928-2932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marchuk, D., M. Drumm, A. Saulino, and F. S. Collins. 1991. Construction of T-vectors, a rapid and general system for direct cloning of unmodified PCR products. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Nishino, S. F., J. C. Spain, and Z. He. 2000. Strategies for aerobic degradation of nitroaromatic compounds by bacteria: process discovery to field application, p. 7-61. In J. C. Spain, J. B. Hughes, and H.-J. Knackmuss (ed.), Biodegradation of nitroaromatic compounds and explosives. Lewis Publishers, Boca Raton, Fla.

- 27.Prakash, D., A. Chauhan, and R. K. Jain. 1996. Plasmid-encoded degradation of p-nitrophenol by Pseudomonas cepacia. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 224:375-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Purwantini, E., T. P. Gillis, and L. Daniels. 1997. Presence of F420-dependent glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase in Mycobacterium and Nocardia species, but absence from Streptomyces and Corynebacterium species and methanogenic Archaea. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 146:129-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Purwantini, E., and L. Daniels. 1998. Molecular analysis of the gene encoding F420-dependent glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase from Mycobacterium smegmatis. J. Bacteriol. 180:2212-2219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rajan, J., K. Valli, R. E. Perkins, F. S. Sariaslani, S. M. Barns, A. L. Reysenbach, S. Rehm, M. Ehringer, and N. R. Pace. 1996. Mineralization of 2,4,6-trinitrophenol (picric acid): characterization and phylogenetic identification of microbial strains. J. Ind. Microbiol. 16:319-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Russ, R., D. M. Walter, H.-J. Knackmuss, and P. E. Rouviere. 2000. Identification of genes involved in picric acid and 2,4-DNP degradation by mRNA differential display, p. 127-143. In J. C. Spain, J. B. Hughes, and H.-J. Knackmuss (ed.), Biodegradation of nitroaromatic compounds and explosives. Lewis Publishers, Boca Raton, Fla.

- 32.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 33.Spain, J. C., and D. T. Gibson. 1991. Pathway for biodegradation of p-nitrophenol in a Moraxella sp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:812-819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takeo, M., Y. Abe, T. Yasukawa, S. Niihara, Y. Maeda, and S. Negoro. 2003. Cloning and characterization of a 4-nitrophenol hydroxylase gene cluster from Rhodococcus sp. PN1. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 95:139-145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tatusov, R. L., E. V. Koonin, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. A genomic perspective on protein families. Science 278:631-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tatusova, T. A., and T. L. Madden. 1999. BLAST 2 Sequences, a new tool for comparing protein and nucleotide sequences. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 174:247-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTALW: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13p18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103-119. [DOI] [PubMed]