Abstract

Whole cells of Rhodococcus ruber DSM 44541 were found to hydrolyze (±)-2-octyl sulfate in a stereo- and enantiospecific fashion. When growing on a complex medium, the cells produced two sec-alkylsulfatases and (at least) one prim-alkylsulfatase in the absence of an inducer, such as a sec-alkyl sulfate or a sec-alcohol. From the crude cell-free lysate, two proteins responsible for sulfate ester hydrolysis (designated RS1 and RS2) were separated from each other based on their different hydrophobicities and were subjected to further chromatographic purification. In contrast to sulfatase RS1, enzyme RS2 proved to be reasonably stable and thus could be purified to homogeneity. Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis revealed a single band at a molecular mass of 43 kDa. Maximal enzyme activity was observed at 30°C and at pH 7.5. Sulfatase RS2 showed a clear preference for the hydrolysis of linear secondary alkyl sulfates, such as 2-, 3-, or 4-octyl sulfate, with remarkable enantioselectivity (an enantiomeric ratio of up to 21 [23]). Enzymatic hydrolysis of (R)-2-octyl sulfate furnished (S)-2-octanol without racemization, which revealed that the enzymatic hydrolysis proceeded through inversion of the configuration at the stereogenic carbon atom. Screening of a broad palette of potential substrates showed that the enzyme exhibited limited substrate tolerance; while simple linear sec-alkyl sulfates (C7 to C10) were freely accepted, no activity was found with branched and mixed aryl-alkyl sec-sulfates. Due to the fact that prim-sulfates were not accepted, the enzyme was classified as sec-alkylsulfatase (EC 3.1.6.X).

Sulfatases (EC 3.1.6.X) catalyze hydrolytic cleavage of the sulfate ester bond by liberating inorganic sulfate and the corresponding alcohol (Fig. 1). They are present in a wide variety of species, ranging from bacteria to humans (18, 25). In contrast to the role of human sulfatases, which are involved in the desulfation of sulfated glycolipids, glycosaminoglycans, and steroids (7, 19), the primary role of bacterial sulfatases is in the assimilation of sulfur (9, 12) or in the provision of carbon and/or energy sources for cell growth (15, 16).

FIG. 1.

Enzymatic hydrolysis of sulfate esters. The asterisk indicates the location of the chiral center.

Our knowledge concerning bacterial sulfatases was summarized in an extensive review in 1982 (12). Alkylsulfatases hydrolyze organic sulfate esters of primary or secondary alkyl alcohols. Most of the work on alkylsulfatases was carried out with two gram-negative bacteria, Pseudomonas sp. strain C12B (= NCIMB 11753 = ATCC 43648) and Comamonas terrigena NCIMB 8193. It was shown that under appropriate culture conditions Pseudomonas sp. strain C12B produced up to five different alkylsulfatases (three secondary and two primary alkylsulfatases, which are specific for the hydrolysis of sec- and prim-alkyl sulfates, respectively) (2, 6, 11). In contrast, C. terrigena produced only two secondary alkylsulfatases irrespective of the culture conditions employed (1, 14). Some of these enzymes have been purified to homogeneity (2, 21).

Alkylsulfatases have mostly been found in gram-negative bacteria; the only exceptions to date are strains of Bacillius cereus (27) and coryneform strain B1a (31) when they are grown on dodecyl sulfate and propyl sulfate, respectively. Although alkylsulfatases have been biochemically characterized to a certain extent, their potential for preparative biohydrolysis of organic sulfate esters in a stereo- and enantioselective fashion is completely unexploited. The only report of stereo- and enantioselective hydrolysis of a sec-alkyl sulfate by an alkyl sulfatase (S1 from Pseudomonas sp. strain C12B) described moderate enantioselectivity (an enantiomeric ratio [E] of ca. 7) for 2-octyl sulfate (33). The potential of these enzymes to affect inversion of a stereogenic center on a sec-carbon atom during catalysis makes them prime candidates for the development of so-called deracemization techniques (13). The potential of alkylsulfatases for stereoselective organic synthesis has been highlighted recently (22, 23), and methods to enhance the enantioselectivity of these enzymes (24) have been developed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Alkyl sulfates.

Sodium sec-(±)-alkyl sulfates were prepared by sulfation of the corresponding sec-alcohols by using the triethylamine-SO3 complex as described by White et al. (32) with small modifications during workup. Spectroscopic data were in agreement with the structures published elsewhere (22).

Organism, growth conditions, and cell disruption.

Cells of Rhodococcus ruber DSM 44541 were grown under aerobic conditions in baffled Erlenmeyer flasks at 30°C and 130 rpm by using medium containing (per liter) 10 g of glucose, 10 g of peptone, 10 g of yeast extract, 2 g of NaCl, 1.5 g of MgSO4 · 7H2O, 1.3 g of NaH2PO4, and 4.4 g of K2HPO4. Cell growth was monitored by measuring the optical density (absorption) at 546 nm. Absorbance values greater than ∼1 were measured after suitable sample dilution. Cells were harvested in the stationary phase. Curves for cell growth and enzyme activity of R. ruber DSM 44541 were determined for a 10-liter fermentation (Braun Biostat ES 10) at 30°C and pH 7.0. Oxygen saturation was kept at 70% and was regulated by stirrer rotation. The sterilized medium was inoculated with 1 liter of a preculture, which was grown in the standard medium for 2 days. Glucose concentration was measured with a glucose (HK) assay kit (Sigma).

Cells were disrupted by using a Vibrogen cell mill with external ice-water cooling (4°C) as follows. To a cell suspension of R. ruber DSM 44541 (47 g [wet weight] of cell paste) in 120 ml of 10 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.5), 120 ml of glass beads (diameter, 0.35 mm) was added. The cells were broken by four shaking cycles consisting of 2 min of agitation and 5 min of cooling each. After removal of the beads by filtration, the crude cell lysate was centrifuged at 4°C and 38,000 × g for 2 h.

Determination of protein concentration.

Protein concentration was measured by the method of Bradford (Coomassie blue protein assay) at 595 nm by using a Bio-Rad protein assay. The protein concentration was determined by using a calibration curve that was established with known concentrations of bovine serum albumin ranging from 0 to 20 μg/ml.

Determination of the molecular mass of the enzyme and the isoelectric point.

Denatured proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (12% polyacrylamide gels; Mini-PROTEAN II dual slab cell; Bio-Rad). Each gel was electrophoresed at 200 V and then stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. Low-molecular-weight SigmaMarker was used as a protein standard for determination of molecular masses.

The isoelectric point of sulfatase RS2 was determined by using a Bio-Rad isoelectric focusing (IEF) Ready Gel system for pH values ranging from 3 to 10. The gel was electrophoresed within a PROTEAN IEF cell and was developed with crocein scarlet. Bio-Rad's IEF standards were used as a reference according to the Bio-Rad manual instructions.

Assay for enzymatic activity based on determination of the inorganic sulfate liberated.

Enzyme activity was measured based on determination of the amount of enzymically liberated inorganic sulfate by using the barium chloride-gelatin method of Dodgson (10) (method B with the modifications of Tudball and Thomas [30]). For the assay, 200 μl of enzyme stock solution was incubated with 200 μl of 3- or 4-octyl sulfate at a final concentration of 15 mM. The reaction was carried out in 0.1 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) at 30°C and was stopped after 15 min by addition of 50 μl of 15% (wt/vol) trichloroacetic acid. After centrifugation for a short time, a 200-μl aliquot was used for determination of the amount of inorganic sulfate. When 2-octyl sulfate was used, the reaction time was extended to 1 to 2 h. The amount of inorganic sulfate was spectrophotometrically measured by determining the absorption at 360 nm in 2-cm quartz cells against a blank by using a barium chloride-gelatin reagent (Difco Bacto Gelatin; Difco Laboratories Detroit, Mich.). One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme which released 1 μmol of SO4−2 ions per min.

Assay for enzyme activity based on determination of the alcohol liberated.

Alternatively, enzymatic activity was measured by determination of the amount of alcohol liberated by using 15 mM substrate in 0.1 M Tris buffer at pH 7.5. Thus, a 400-μl aliquot of an enzyme solution was mixed with 400 μl of a 30 mM substrate solution in 0.1 M Tris buffer (pH 7.5). The substrate and enzyme were shaken at 24°C at 130 rpm for 6 or 12 h, depending on the type of substrate.

Determination of conversion.

A 200-μl aliquot of the reaction mixture was extracted with 200 μl of ethyl acetate. After vigorous vortexing (30 s) and centrifugation (12,200 × g, 5 min), 100 μl of the organic phase was mixed with a stock solution containing 5 μl (or 25 μl) of menthol in ethanol (15.4 mg/ml [or 77 mg/ml]), which served as an internal standard. Conversion was determined by gas chromatography (GC) on an achiral phase (HP 1301 [30 m by 0.25 mm, 0.25 μm] and HP-1 [30 m by 0.53 mm, 0.5 μm]; N2) by starting at 90°C (2.5-min hold) and increasing the temperature at a rate of 10°C/min until a plateau of 110°C was reached. Due to the high lipophilicity of the products formed (2-, 3-, and 4-octanol), a single extraction was sufficient for total recovery (≥97%). The conversion was calculated from the calibration curves for 2-, 3-, and 4-octanol. Control experiments in the absence of enzyme revealed that the spontaneous hydrolysis of substrates was negligible (≤3%) in the time period used.

Determination of enantiomeric excess and absolute configuration of the product.

The enantiomeric composition of the alcohols formed (enantiomeric excess of product [eeP]) was determined by GC by using the following chiral stationary phases with H2 as the carrier gas: Chrompack CP7500 (25 m by 0.25 mm, 25 μm) and Chrompack Chirasil-Dex CB/G-PN (30 m by 0.32 mm). For determination of the enantiomeric composition, the alcohol had to be derivatized with trifluoroacetic anhydride prior to analysis in order to achieve enantioseparation. Thus, a 400-μl sample from the enzyme reaction mixture was extracted with 500 μl of CH2Cl2 and dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate. After addition of 40 μl of trifluoroacetic anhydride, the sample was heated in a capped vial at 60°C for 20 min. After it was cooled to room temperature, the sample was extracted twice with 0.5 ml of a 5% sodium bicarbonate solution. After final drying of the organic phase over anhydrous sodium sulfate, the sample was subjected to GC analysis.

The absolute configuration of products was elucidated by allocation of the peaks via coinjection with an independent reference sample containing (R)- or (S)-alcohol. The following retention times for corresponding alkyl trifluoroacetates were obtained with a CP7500 column: for 2-octanol (isotherm at 65°C), 7.66 min for the (S) form and 8.00 min for the (R) form; for 3-octanol (isotherm at 60°C), 7.65 min for the (S) form and 8.08 min for the (R) form; and for 4-octanol (isotherm at 55°C), 7.84 min for the (S) form and 8.11 min for the (R) form.

Enzyme purification.

Crude cell lysate was dialyzed against 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5). In order to remove mucous components and carotenoids from the cells, which impeded protein chromatography, the lysate was pretreated with DEAE-cellulose in a batch procedure (100 mg of protein per 2.5 g of DEAE-cellulose). Proteins were eluted from the carrier by using 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) containing 0.5 M NaCl. This crude enzyme extract was mixed with stirring (on ice) with NaCl to obtain a final NaCl concentration of 4 M and was applied to a phenyl Sepharose high-performance column (20 ml; Pharmacia). The column was equilibrated with 80 ml of buffer B (10 mM Tris-HCl buffer containing 4 M NaCl [pH 7.5]). Proteins were eluted in a stepwise fashion by using a gradient with buffer A (10 mM Tris-HCl buffer [pH 7.5]). Enzyme RS2 was liberated at 0% buffer B (see Fig. 3). After repeated dialysis against 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5), active fractions were subjected to further purification by ion-exchange chromatography by using a Q6 column (total volume, 6 ml; Bio-Rad) equilibrated with the same buffer. Proteins were eluted with buffer C (10 mM Tris-HCl buffer [pH 7.5], 1 M NaCl) by using a linear 0 to 1 M NaCl gradient at a flow rate of 4 ml/min. Desorption of enzyme RS2 took place at 15 to 31% buffer C. In the following step, a Blue Sepharose column (8 ml; Pharmacia) was used. Fractions containing RS2 were applied to the column in 10 mM piperazine buffer (pH 6.0). Under these conditions, sulfatase RS2 did not bind to the column and thus could be collected immediately. The column was washed with Tris-glycine buffer (pH 8.9) (3 g of Tris per liter, 2.6 g of glycine per liter). Finally, the active fractions were concentrated to 1 ml (Centriplus 10; Amicon) and applied to a Superdex 200 column. The equilibration and elution buffer was 50 mM NaH2PO4 containing 0.15 M NaCl (pH 7.0).

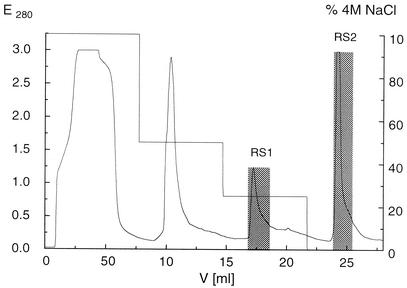

FIG. 3.

Separation of RS2 from RS1 by hydrophobic chromatography. A stepwise NaCl gradient was used. The gray bars indicate alkylsulfatases RS1 and RS2.

RESULTS

Sulfatase activity and growth of R. ruber DSM 44541.

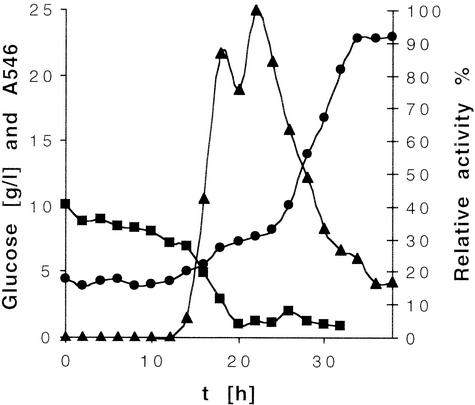

R. ruber DSM 44541 was cultivated on a complex medium containing glucose, peptone, yeast extract, and mineral salts. Under these conditions, the cells produced two sec-alkylsulfatases and (at least) one prim-alkylsulfatase in the absence of an inducer, such as a sec-alkyl sulfate or a sec-alcohol. The primary alkylsulfatase showed a strong preference for SDS and was not investigated further, since it was not expected to possess significant stereo- or enantioselectivity. The sec-alkylsulfatase activity was measured during growth in an 11-liter batch fermentation by using (±)-2-octyl sulfate (Fig. 2). Besides the desired biohydrolysis of the sec-sulfate ester yielding 2-octanol, further metabolism of the latter product by oxidation, yielding 2-octanone, was observed to a certain extent when whole cells were used. This activity could be attributed to the action of a nicotinamide-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase (29). The curve of relative sec-sulfatase activity versus cell growth (Fig. 2) reflects the regulation pattern typical for catabolite repression, and thus the activity is most probably coupled to the energy level of the cell. No biohydrolysis was detected in the presence of elevated glucose concentrations (≥7 g/liter), and enzyme expression was initiated only upon depletion of the glucose. The cells were harvested in the late exponential phase of growth.

FIG. 2.

Alkylsulfatase activity and cell growth of R. ruber DSM 44541. Symbols: ▪, glucose concentration; •, optical density (A546); ▴, relative sulfatase activity. The relative activities of whole cells were measured by using (±)-2-octyl sulfate as a substrate.

Enzyme purification.

The purification procedure was started by using the crude cell-free lysate after disruption of the cells with a cell mill. Serious filtration problems due to the presence of mucous substances, such as carotenoids, lipids, and various surface-active components, which were released from the cells during disruption, were overcome by pretreating the lysate with DEAE-cellulose in a batch procedure. The different hydrophobicities of enzymes enabled separate elution of two sec-alkylsulfatases, which were arbitrarily designated RS1 and RS2 (RS stands for Rhodococcus sulfatase), by using phenyl Sepharose high-performance material in the first step (Fig. 3). The presence of inorganic sulfate and thus the possibility of product inhibition were avoided by using a sodium chloride solution in a stepwise gradient instead of a more commonly used sulfate-containing salt, such as (NH4)2SO4.

Active fractions containing RS2, which were well separated from RS1, were further purified by interaction with an anion-exchange resin, followed by dye chromatography and final purification on a Superdex 200 size exclusion column (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Purification of sec-alkylsulfatase RS2 from R. ruber DSM 44541

| Step | Vol (ml) | Protein (mg) | Enzyme activity (u) | Sp ac (U/mg) | % Recoverya | Purification (fold)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell extract | 60 | 732 | 42.6 | 0.058 | 100 | 1 |

| DEAE-cellulose batch | 133 | 532 | 43.9 | 0.083 | 100 | 1.4 |

| Phenyl Sepharose | 60 | 103.8 | 18.0 | 0.173 | 42 | 3 |

| Q6 | 60 | 41.2 | 12.6 | 0.306 | 30 | 5.3 |

| Blue Sepharose | 56 | 3.3 | 7.1 | 2.15 | 17 | 37 |

| Superdex 200 | 28 | 0.45 | 3.1 | 6.88 | 7.3 | 119 |

Percentage of the initial enzyme activity.

Specific activity/0.058.

The purification sequence allowed us to purify alkylsulfatase RS2 119-fold from the crude cell extract in a reproducible way. Use of NaCl as the salting-out medium for hydrophobic interaction chromatography appeared to be necessary since use of (NH4)2SO4 resulted in enzyme deactivation and thus difficulties in sulfatase detection. Due to the reduced ionic strength of sodium chloride, use of this compound required higher starting concentrations than the ammonium sulfate starting concentrations. An NaCl concentration of 4 M was required to ensure reproducible quantitative binding of the sulfatase activity to the column. In the purification protocol used for alkylsulfatase S3 from Pseudomonas strain C12B, Blue Sepharose was reported to cause selective binding of the protein to the matrix (26), which was explained by the favorable interaction between the sulfatase and the (substrate-like) arenesulfonate groups of the affinity ligand. When the same strategy was used during purification of the RS2 enzyme, we obtained a significant breakthrough in purification, but opposite binding properties were observed. The enzyme did not interact with the affinity ligand, regardless of the conditions used. Pure alkylsulfatase RS2 had a specific activity of 6.88 ± 0.52 U/mg.

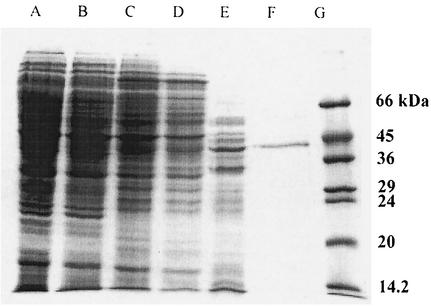

Molecular mass and isoelectric point determination.

The elution profile of the purified enzyme on Superdex 200 indicated that the molecular mass of the native enzyme is ca. 67 kDa. However, SDS-PAGE revealed the presence of a single band at about 43 kDa for RS2 (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

SDS-PAGE analysis of proteins during purification of alkylsulfatase RS2. Lane A, crude cell extract; lane B, batch DEAE-cellulose; lane C, phenyl Sepharose; lane D, Q6; lane E, Blue Sepharose; lane F, Superdex 200; lane G, low-molecular-mass markers. The gel was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R. The gel was a 12% polyacrylamide gel.

The pI of the enzyme was 5.1. This finding was supported by the fact that the enzyme was unstable at a pH lower than 6, which resulted in precipitation from the protein mixture.

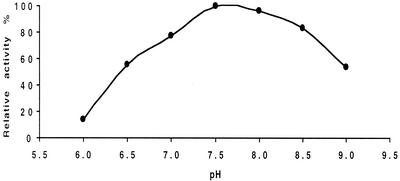

Temperature and pH optima.

The effects of pH and temperature on the enzyme activity are shown in Fig. 5 and 6. The pH stability was tested at 24°C in 100 mM Tris-maleate buffer by using a pH range from 6.0 to 9.0 with 15 mM (±)-2-octyl sulfate as the substrate. The maximum activity was observed at a rather narrow range, between pH 7.5 and 8.0.

FIG. 5.

pH optimum for sulfatase RS2 activity.

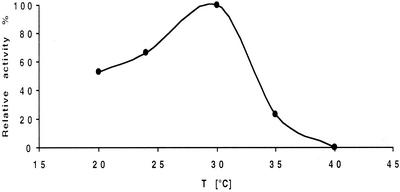

FIG. 6.

Temperature optimum for sulfatase RS2 activity.

The effect of temperature on the hydrolysis of (±)-2-octyl sulfate was determined in 100 mM Tris-maleate buffer at pH 7.5 by using temperatures ranging from 20 to 40°C. Whereas about 50% of the maximum activity was observed at 20°C, a sharp optimum was found at 30°C. At higher temperatures, the activity declined rapidly, presumably due to enzyme deactivation. No activity was found at 40°C.

Substrate tolerance.

The sec-alkyl sulfates accepted as substrates by enzyme RS2 were compounds with chain lengths ranging from 7 to 10 carbon atoms, and there was clearly maximum activity with C8 derivatives (22). The preferred substrates for the enzyme were linear sec-alkyl sulfate esters, particularly 2-, 3-, and 4-octyl sulfates. Again, there was a certain similarity to inducible secondary alkylsulfatase S3 from Pseudomonas strain C12B, whose activity was centered on symmetrical alkylsulfate esters, such as 4-heptyl sulfate or 5-nonyl sulfate, as well as various nonsymmetrical C3-and C4-substituted alkyl sulfate esters (26). On the other hand, this is in contrast to the behavior of secondary alkylsulfatases S1 and S2 from Pseudomonas strain C12B and of CS2 from C. terrigena, which showed a striking affinity for 2-alkyl sulfates.

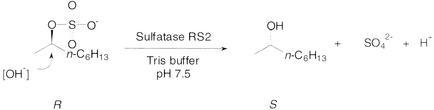

Stereochemical pathway of enzymatic sulfate ester hydrolysis.

In order to determine the stereochemical pathway of sulfate ester bond cleavage with respect to retention or inversion of the stereogenic chiral center, enantiomerically pure (R)-2-octyl sulfate was used as a substrate for purified enzyme RS2. GC analysis of a chiral stationary phase revealed that (S)-(+)-2-octanol was the only product of the enzymatic hydrolysis. Consequently, we concluded that the reaction proceeded through nucleophilic attack at the sec-carbon atom via Walden inversion occurring together with inversion of the configuration at the C2 atom. This mechanism, which is facilitated by the leaving-group properties of the sulfate ion, is common to all sec-alkylsulfatases investigated so far (3, 33); opposite pathways were reported for d-lactate-2-sulfatase from Pseudomonas syringae (8) and arylsulfatases (28). Thus, the mechanistic action of RS2 involves breaking of the C—O bond, thus affecting absolute inversion of the configuration (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Stereochemical course of enzymatic sulfate ester hydrolysis.

When a crude cell extract was used for hydrolysis of (R)-2-octyl sulfate, a trace amount of (R)-2-octanol was formed. As previously observed, R. ruber DSM 44541 contains (at least) two nicotinamide-dependent alcohol dehydrogenases, which are able to catalyze the stereoinversion of sec-alcohols via oxidation-reduction of 2-octanol-2-octanone (29). As a consequence, formation (of the minor amount) of (R)-2-octanol could be attributed to stereoinversion via this redox system (4) and was not due to incomplete stereoselectivity of the alkylsulfatases involved (i.e., a pathway involving retention).

Determination of enantioselectivity.

The enantioselectivity of sulfatase RS2 was expressed by E, which is the ratio of the relative first-order reaction rates of enantiomers and was calculated from eeP and conversion (c) according to the following equation (5).

|

(1) |

Our data provide the first quantitative values for the enantioselectivity of a sec-alkylsulfatase, and they indicate that use of this enzyme for resolution and/or deracemization of sec-alcohols via biohydrolysis of their corresponding sec-sulfate esters is indeed very promising. Hydrolysis of (±)-2-octyl sulfate by enzyme RS2 proceeded with an E of 21, whereas the selectivity of (±)-3-octyl sulfate was reduced to a modest E (4.3). Virtually no enantioselectivity was observed for (almost symmetric) 4-octyl sulfate, which was converted to (almost) racemic 4-octanol. It should be emphasized that the enantioselectivity of the native unmodified enzyme RS2 could be dramatically increased by addition of certain selectivity-enhancing additives (24).

DISCUSSION

The molecular mass of the native RS2 enzyme (ca. 67 kDa as determined by the elution profile on a size exclusion column and 43 kDa as determined by SDS-PAGE) (Fig. 4) suggests that the enzyme is nonglobular and thus indicates that the protein is monomeric. However, this enzyme appears to be much smaller than the previously described alkylsulfatases S1 from Pseudomonas strain C12B and CS2 from C. terrigena, which have molecular masses of approximately 250 kDa (2, 21), and it seems to be more closely related to the inducible enzyme S3 from Pseudomonas strain C12B (molecular mass, 40 to 46 kDa) (26).

Since addition of EDTA did not eliminate enzyme activity, we presume that RS2 does not possess any metal ions that are needed as cofactors for catalytic activity.

A careful survey of the previously published data for alkylsulfatases revealed that enantioselectivity (i.e., the preferred hydrolysis of one substrate enantiomer over its antipode) has been observed for this type of enzyme, but this behavior has never been accurately quantified. The first indication of the enantioselectivity of sec-alkylsulfatases was the chance observation that some racemic alkyl sulfates could be rapidly hydrolyzed to 50% conversion, whereas the remainder of the hydrolysis took place at a very reduced rate or not at all (20, 26). In spite of this observation, only a single report on the enantioselectivity of alkylsulfatases has been published to date (33). Thus, the stereo- and enantioselective hydrolysis of (±)-2-octyl sulfate by sulfatase S1 from Pseudomonas strain C12B furnished 2-octanol in 58% enantiomeric excess at 50% conversion, which corresponds to a moderate enantioselectivity (an E of ca. 7). The stereoselective biohydrolysis of sulfate esters is very interesting in view of the practical application of sulfatases for preparative-scale transformations. It should be emphasized that this transformation is impossible when a conventional (chemical) methodology is used. When (±)-2-octyl sulfate was used as a substrate, enzyme RS2 showed a clear preference for (R)-2-octyl sulfate, as reflected by a remarkable E, 21. When rather symmetrical molecules, such as 3- or 4-octyl sulfate, are used, the chiral recognition process gets more difficult as the relative sizes of the two alkyl groups adjacent to the stereogenic sulfate ester group become more similar. Although the enantioselectivity for 3-octyl sulfate is low (E = 4.3), the enantiopreference is still (R); however, product analysis for the biohydrolysis of (±)-4-octyl sulfate revealed the formation of 4-octanol in (almost) racemic form. This is not surprising considering that this molecule is not far from symmetric.

Two models of substrate binding within the active site of the enzyme have been proposed for enzyme CS2 from C. terrigena (21) and for the inducible alkylsulfatase S3 from Pseudomonas strain C12B (26). The basis of both proposals is a three-point interaction between enzyme and substrate. Whereas the main force of attraction is presumably the (strong) ionic binding of the (negatively charged) sulfate ester group, both of the remaining (hydrophobic) interactions are comparably weak due to the lipophilic character of the alkyl groups of the substrate. As a consequence, the chiral recognition process is dominated by the relative size of substituents of the substrate, similar to lipases (17). This explains why (±)-2-octyl sulfate was resolved with good selectivity, whereas the E values decreased dramatically when nearly symmetrical substrates were used. We therefore assume that sulfatase RS2 possesses two hydrophobic binding sites that are different in size, one preferring a large group and one preferring a smaller alkyl group.

In conclusion, we believe that the sec-alkylsulfatase RS2 from R. ruber DSM 44541 described in this paper represents a promising new tool for stereo- and enantioselective biohydrolysis of sulfate esters of sec-alcohols. No counterpart of this reaction exists in traditional chemical methodology. Because the mechanism of action proceeds with inversion of configuration, homochiral product mixtures, which have the same absolute configuration consisting of an (S)-alcohol and a remaining nonhydrolyzed (S)-sulfate ester, are obtained from kinetic resolution of the racemate. After cleavage of the sulfate group from the residual (S)-ester with complete retention of configuration, a single enantiomeric sec-alcohol should be the sole product from the racemate, with a 100% theoretical yield. Chemical catalysts for the latter transformation are being developed in our laboratories. The whole sequence constitutes a deracemization, which represents a dramatic improvement in the economic balance compared to traditional kinetic resolution, which is limited to 50% of each enantiomer (13).

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank Degussa for financial support of this project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barrett, C. H., K. S. Dodgson, and G. F. White. 1980. Further studies on the substrate specificity and inhibition of the stereospecific CS2 secondary alkylsulphohydrolase of Comamonas terrigena. Biochem. J. 191:467-473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartholomew, B., K. S. Dodgson, and S. D. Gorham. 1978. Purification and properties of the S1 secondary alkylsulphohydrolase of the detergent-degrading microorganism, Pseudomonas C12B. Biochem. J. 169:659-667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartholomew, B., K. S. Dodgson, G. W. J. Matcham, D. J. Shaw, and G. F. White. 1977. A novel mechanism of enzymic ester hydrolysis. Biochem. J. 165:575-580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carnell, A. J. 1999. Stereoinversions using microbial redox-reactions. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 63:57-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, C.-S., Y. Fujimoto, G. Girdaukas, and C. J. Sih. 1982. Quantitative analyses of biochemical kinetic resolutions of enantiomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 104:7294-7299. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cloves, J. M., K. S. Dodgson, G. F. White, and J. W. Fitzgerald. 1980. Specificity of P2 primary alkylsulphohydrolase induction in the detergent-degrading bacterium Pseudomonas C12B. Biochem. J. 185:13-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coughtrie, M. W. H., S. Sharp, K. Maxwell, and N. P. Innes. 1998. Biology and function of the reversible sulfation pathway catalysed by human sulfotransferases and sulfatases. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 109:3-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crescenzi, A. M., K. S. Dodgson, and G. F. White. 1984. Purification and some properties of the d-lactate-2-sulphatase of Pseudomonas syringae GG. Biochem. J. 223:487-494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Denger, K., and A. M. Cook. 1997. Assimilation of sulfur from alkyl- and arylsulfonates by Clostridium spp. Arch. Microbiol. 167:177-181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dodgson, K. S. 1961. Determination of inorganic sulphate in studies on the enzymic and non-enzymic hydrolysis of carbohydrate and other sulphate esters. Biochem. J. 78:312-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dodgson, K. S., J. W. Fitzgerald, and W. J. Payne. 1974. Chemically defined inducers of alkylsulphatases present in Pseudomonas C12B. Biochem. J. 138:53-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dodgson, K. S., G. F. White, and J. W. Fitzgerald. 1982. Sulfatases of microbial origin. CRC Press Inc., Boca Raton, Fla.

- 13.Faber, K. 2001. Non-sequential processes for the transformation of a racemate into a single stereoisomeric product: proposal for stereochemical classification. Chem. Eur. J. 7:5004-5010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitzgerald, J. W., K. S. Dodgson, and G. W. J. Matcham. 1975. Secondary alkylsulphatases in a strain of Comamonas terrigena. Biochem. J. 149:477-480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fitzgerald, J. W., and L. C. Kight. 1977. Physiological control of alkylsulfatase synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: effects of glucose, glucose analogs, and sulfur. Can. J. Microbiol. 23:1456-1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fitzgerald, J. W., L. C. Kight-Olliff, G. J. Stewart, and N. F. Beauchamp. 1978. Reversal of succinate-mediated catabolite repression of alkylsulfatase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by 2,4-dinitrophenol and by sodium malonate. Can. J. Microbiol. 24:1567-1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kazlauskas, R. J., A. N. E. Weissfloch, A. T. Rappaport, and L. A. Cuccia. 1991. A rule to predict which enantiomer of a secondary alcohol reacts faster in reactions catalyzed by cholesterol esterase, lipase from Pseudomonas cepacia and lipase from Candida rugosa. J. Org. Chem. 56:2656-2665. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kertesz, M. A. 1999. Riding the sulfur cycle—metabolism of sulfonates and sulfate esters in Gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 24:135-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lowe, G. 1997. Sulfotransferases, comprehensive biological catalysis-a mechanistic reference, vol. 1, p. 627-635. Academic Press Ltd., London, United Kingdom.

- 20.Matcham, G. W. J., B. Bartholomew, K. S. Dodgson, J. W. Fitzgerald, and W. J. Payne. 1977. Stereospecificity and complexity of microbial sulphohydrolases involved in the biodegradation of secondary alkylsulphate detergents. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1:197-200. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matcham, G. W. J., K. S. Dodgson, and J. W. Fitzgerald. 1977. Purification, properties and cellular localization of the stereospecific CS2 secondary alkylsulphohydrolase of Comamonas terrigena. Biochem. J. 167:723-729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pogorevc, M., and K. Faber. 2002. Enantioselective stereoinversion of sec-alkyl sulfates by an alkylsulfatase from Rhodococcus ruber DSM 44541. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 13:1435-1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pogorevc, M., W. Kroutil, S. R. Wallner, and K. Faber. 2002. Enantioselective stereoinversion in the kinetic resolution of rac-sec-alkyl sulfate esters by hydrolysis with an alkylsulfatase from Rhodococcus ruber DSM 44541 furnishes homochiral products. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 41:4052-4054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pogorevc, M., U. T. Strauss, T. Riermeier, and K. Faber. 2002. Selectivity-enhancement in enantioselective hydrolysis of sec-alkyl sulfates by an alkylsulfatase from Rhodococcus ruber DSM 44541. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 13:1443-1447. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roy, A. B. 1971. Hydrolysis of sulfate esters. Enzymes 5:1-19. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaw, D. J., K. S. Dodgson, and G. F. White. 1980. Substrate specificity and other properties of the inducible S3 secondary alkylsulphohydrolase purified from the detergent-degrading bacterium Pseudomonas C12B. Biochem. J. 187:181-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh, K. L., A. Kumar, and A. Kumar. 1998. Short communication: Bacillus cereus capable of degrading SDS shows growth with a variety of detergents. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 14:777-779. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spencer, B. 1958. Studies on sulphatases. 20. Enzymic cleavage of aryl hydrogen sulphates in the presence of H218O. Biochem. J. 69:155-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stampfer, W., B. Kosjek, C. Moitzi, W. Kroutil, and K. Faber. 2002. Biocatalytic asymmetric hydrogen transfer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 41:1014-1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tudball, N., and P. Thomas. 1967. Studies on the enzymic degradation of l-serine O-sulphate by a rat liver preparation. Biochem. J. 105:467-472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.White, G. F., K. S. Dodgson, I. Davies, P. J. Matts, J. P. Shapleigh, and W. J. Payne. 1987. Bacterial utilization of short-chain primary alkyl sulfate esters. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 40:173-177. [Google Scholar]

- 32.White, G. F., V. Lillis, and D. J. Shaw. 1980. An improved procedure for the preparation of alkyl sulphate esters for the study of secondary alkylsulphohydrolase enzymes. Biochem. J. 187:191-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White, G. F. 1991. Enantiomeric enrichment of R-(−)-alkan-2-ols using a stereospecific alkylsulphatase. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 35:312-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]