Abstract

We previously observed secretion of active-form transglutaminase in Corynebacterium glutamicum by coexpressing the subtilisin-like protease SAM-P45 from Streptomyces albogriseolus to process the prodomain. However, the N-terminal amino acid sequence of the transglutaminase differed from that of the native Streptoverticillium mobaraense enzyme. In the present work we have used site-directed mutagenesis to generate an optimal SAM-P45 cleavage site in the C-terminal region of the prodomain. As a result, native-type transglutaminase was secreted.

Transglutaminases (protein-glutamine γ-glutamyltransferase [EC 2.3.2.13]) are a family of enzymes that catalyze an acyl transfer reaction between a γ-carboxyamide group of a glutamine residue in a peptide chain and a γ-amino group of a lysine residue, resulting in the formation of an ε-(γ-glutamyl) lysine cross-linkage (2). Transglutaminases are widely distributed, and their physiological properties have been studied. Animal transglutaminases are calcium-dependent enzymes (2, 12, 17), while calcium-independent transglutaminases have been discovered in bacteria belonging to the actinomycetes (1, 16). Streptoverticillium mobaraense transglutaminase (mature-form transglutaminase [MTG]) has been used in the food industry to modify protein (3, 7, 11). Presently the enzyme is produced by conventional fermentation, but it would be desirable to develop a more efficient system for its production.

Corynebacterium glutamicum is gram positive and is employed for the industrial production of amino acids, such as glutamate and lysine, that have been used in human food, animal feed, and pharmaceutical products for several decades (6). It is nonpathogenic and produces no hazardous toxins (6, 10). In a previous report we demonstrated that the pro-MTG was efficiently secreted by C. glutamicum when it carried a signal peptide derived from a cell surface protein of corynebacteria. Moreover, the proenzyme was processed to the active form of the enzyme by the subtilisin-like protease, SAM-P45, when the latter was cosecreted with the proenzyme (5). However, the N-terminal amino acid sequence of the processed transglutaminase differed from that of the native enzyme: four amino acid residues, Phe-Arg-Ala-Pro, at the C terminus of the prodomain were added. We have introduced a preferred SAM-P45 cleavage site at the C terminus of the prodomain in order to produce native-type MTG in C. glutamicum.

Deletion analyses of the prodomain.

DNA manipulations were carried out by the methods described by Sambrook et al. (13). PCR with Pyrobest DNA polymerase (Takara Shuzo, Kyoto, Japan) was performed in 50-μl reaction mixtures for 5 min at 94°C, followed by 25 cycles of 10 s at 98°C, 30 s at 55°C, and 3 min at 72°C. Nucleotide sequences were determined by using a BigDye terminator cycle-sequencing FS ready reaction kit (Applied Biosystems) and a DNA sequencer (model 377; Applied Biosystems).

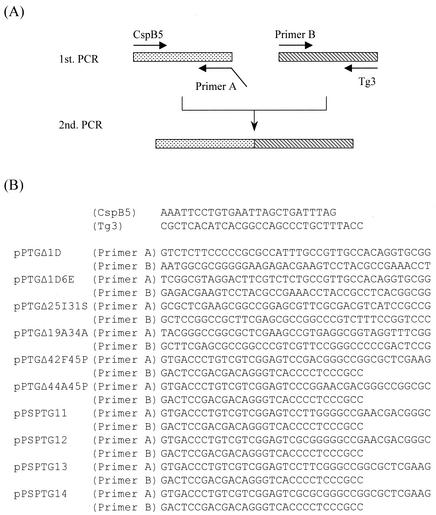

Plasmids expressing pro-MTG with N-terminal, central, or C-terminal deletions (Δ1D, Δ1D6E, Δ25I31S, Δ19A34A, Δ42F45P, and Δ44A45P) were constructed by crossover PCR (Fig. 1 and 2A). First PCRs were performed with CspB5 (as forward primer) and primer A (as reverse primer) or with primer B (as forward primer) and Tg3 (as reverse primer) with plasmid pPSPTG1 DNA (5) as a template (Fig. 1). Second PCRs were performed with CspB5 (as forward primer) and Tg3 (as reverse primer) with the amplified fragments generated by the first PCRs as templates (Fig. 1). Each amplified fragment was digested with ScaI and EcoO65I, and the digested fragments were inserted into the ScaI-EcoO65I site of pPSPTG1 to obtain pPTG1Δ1D, pPTG1Δ1D6E, pPTG1Δ25I31S, pPTG1Δ19A34A, pPTG1Δ42F45P, and pPTG1Δ44A45P. All cloned fragments made by PCR were sequenced to check for PCR-induced errors.

FIG. 1.

Construction of prepro-MTG genes with deleted or mutated prodomains by crossover PCR. (A) Schematic representation of crossover PCR with primer CspB5 and primer A, primer B and Tg3 for first PCRs, and primers CspB5 and Tg3 for second PCR. (B) Primer sequences.

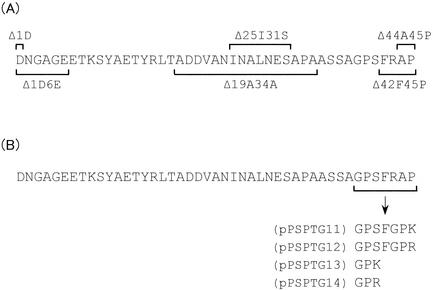

FIG. 2.

Structures of the deleted or mutated prodomains. (A) Deleted prodomains. Each deleted region is indicated by a line above it (Δ1D, Δ25I31S, or Δ44A45P) or is underlined (Δ1D6E, Δ19A34A, or Δ42F45P). (B) Mutated prodomains. The mutated region (GPSFRAP) of the prodomain is underlined. The plasmids expressing prepro-MTG genes with mutated prodomains GPSFGPK, GPSFGPR, GPK, and GPR are pPSPTG11, pPSPTG12, pPSPTG13, and pPSPTG14, respectively.

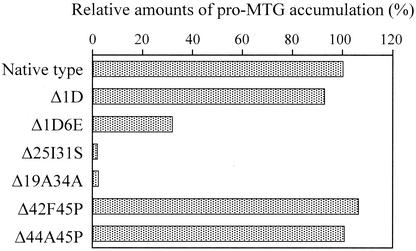

C. glutamicum ATCC 13869 was transformed with pPSPTG1, pPTG1Δ1D, pPTG1Δ1D6E, pPTG1Δ25I31S, pPTG1Δ19A34A, pPTG1Δ42F45P, and pPTG1Δ44A45P (9). The transformants were cultured in MMTG medium (5) containing 25 mg of kanamycin per liter at 30°C for 40 h, and secretion of the corresponding pro-MTG was assessed by high-performance liquid chromatography as described previously (5). Accumulation of the pro-MTGs with central deletions (Δ25I31S and Δ19A34A) was greatly decreased (about 1% of the intact pro-MTG) (Fig. 3) and removing six amino acid residues from the N terminus of the prodomain (Δ1D6E) reduced the amount of secreted pro-MTG to approximately one-third. However, removal of one amino acid residue from the N terminus (Δ1D) or either two or four from the C terminus (Δ44A45P or Δ42F45P) had hardly any effect on the amount of pro-MTG secreted. Evidently the central region of the prodomain, but not the C terminus, has an important role in secretion. We therefore explored the possibility of mutating the C-terminal region of the proprotein in order to produce native-type MTG by SAM-P45 processing.

FIG. 3.

Secretion of prodomains harboring deletions. Values are averages of two independent experiments. The value for the amount of the pro-MTG accumulation with the native-type prodomain was set at 100% for each experiment.

Mutational analysis of C-terminal region.

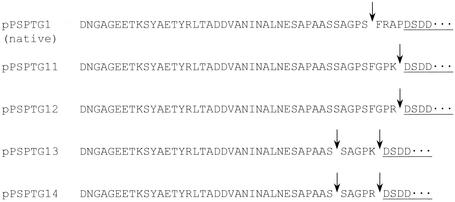

Suzuki et al. (14) have shown that SAM-P45 exhibits strong hydrolytic activity towards tripeptide substrates whose amino acid residues C terminal of the cleavage site are Lys or Arg, preferably in the sequence Gly-Pro-Lys or Gly-Pro-Arg. Plasmids expressing pro-MTGs with prodomains whose C termini had optimal SAM-P45 cleavage sites were constructed by crossover PCR (Fig. 1 and 2B). Each amplified fragment was digested with ScaI and EcoO65I, and the digested fragments with their prodomain deletions were inserted into the ScaI-EcoO65I site of pPSPTG1 to yield pPTG11, pPTG12, pPTG13, and pPTG14. C. glutamicum ATCC 13869 was transformed with these constructs, and the transformants were grown as described above. The accumulation of pro-MTG in these cultures is shown in Table 1, and as expected, none of the mutations in the C terminus of the prodomain had much effect on the amount of secreted pro-MTG. The culture supernatants were incubated with purified SAM-P45 for 2 h at a 100:1 ratio of pro-MTG to SAM-P45. After this, they were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (8), and the proteins were electroblotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad). The segment of gel containing active-form MTG was cut out, and N-terminal amino acid sequences were determined as described earlier (4). The N-terminal amino acid of the pPSPTG11 and pPSPTG12 MTGs was Asp, as in native S. mobaraense MTG (Fig. 4). However, Ser37 of the prodomain was detected N terminally in the pPSPTG13 and pPSPTG14 MTGs in addition to Asp (Fig. 4). The ratio of Ser N termini to Asp N termini was approximately 3 to 2 in both.

TABLE 1.

Relative amounts of pro-MTG accumulation in the culture supernatant of C. glutamicum

| Plasmid | Relative amt of pro-MTG accumulation (%) |

|---|---|

| pPSPTG1 (GPSFRAP/native type) | 100 |

| pPSPTG11 (GPSFGPK) | 93 |

| pPSPTG12 (GPSFGPR) | 84 |

| pPSPTG13 (GPK) | 84 |

| pPSPTG14 (GPR) | 93 |

FIG. 4.

Sites of SAM-P45 cleavage of pro-MTGs with mutated prodomains. The amino acid sequence of the MTG is underlined, and the site of SAM-P45 cleavage is indicated by an arrow.

Production of native-type MTG in C. glutamicum.

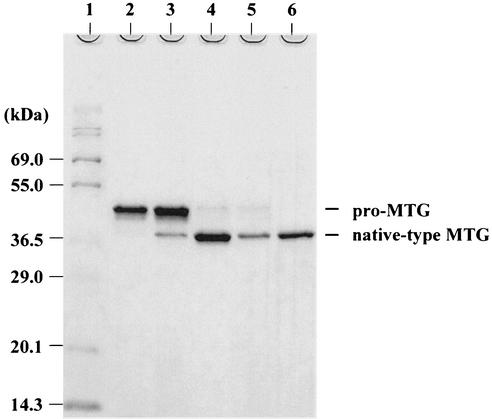

In light of these results, we used pPSPTG11 to produce native-type MTG in C. glutamicum. pPSPTG11 alone and pVSS1 expressing SAM-P45 were introduced into C. glutamicum ATCC 13869, and a transformant was cultured in MMTG at 30°C for 70 h. At various times samples of the supernatant were subjected to SDS-PAGE. The pro-MTG derived from pPSPTG11 was processed by SAM-P45, and accumulation of native-type MTG was maximal at about 70 h (Fig. 5). The maximal accumulation of native-type MTG achieved to date under these condition is 132 mg/liter. The N-terminal amino acid of the secreted native-type MTG is Asp, indicating that the modified prodomain is processed in vitro. Using the methods described by Yokoyama et al. (18), we purified the MTG from S. mobaraense, the active-form MTG with additional Phe-Arg-Ala-Pro residues (5), and the native-type MTG in this report. The specific activities of these enzymes were determined by the calorimetric hydroxamate procedure as described by Yokoyama et al. (18), and the following results were obtained: specific activities of the MTG from S. mobaraense, the active-form MTG with additional Phe-Arg-Ala-Pro residues (5), and the native-type MTG used for this report were 26, 30, and 26 U/mg, respectively.

FIG. 5.

SDS-PAGE analysis of the active-form MTG produced by C. glutamicum carrying plasmids expressing pro-MTG and SAM-P45. Ten microliters of supernatant and an equal volume of sample buffer were applied to each slot and were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. After electrophoresis, the gel was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250. Lane 1, molecular weight markers; lanes 2 through 5, culture supernatants after 30, 45, 70, and 140 h of cultivation; and lane 6, purified MTG from S. mobaraense.

In this study we have obtained efficient secretion of native-type MTG by C. glutamicum by using an altered prodomain and coexpressing SAM-P45. The accumulation of MTG (132 mg/liter) exceeded that in other hosts, since no more than 0.1 and 5 mg of MTG per liter were secreted by Streptomyces lividans (16) and Escherichia coli (15), respectively. This C. glutamicum protein expression and cleavage system is therefore useful for producing a heterologous protein with an N-terminal amino acid sequence identical to that of the native form.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to S. Taguchi for his kind gift of purified SAM-P45 and to N. Onishi for helpful discussion.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ando, H., M. Adachi, K. Umeda, A. Matsuura, M. Nonaka, R. Uchio, H. Tanaka, and M. Motoki. 1989. Polymerization and characteristics of a novel transglutaminase derived from microorganisms. Agric. Biol. Chem. 53:2619-2623. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Folk, J. E. 1980. Transglutaminases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 49:517-531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ikura, K., R. Sasaki, and M. Motoki. 1992. Use of transglutaminase in quality-improvement and processing of food proteins. Agric. Food Chem. 2:389-407. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kikuchi, Y., H. Kojima, T. Tanaka, Y. Takatsuka, and Y. Kamio. 1997. Characterization of a second lysine decarboxylase isolated from Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 179:4486-4492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kikuchi, Y., M. Date, K. Yokoyama, Y. Umezawa, and H. Matsui. 2003. Secretion of active-form Streptoverticillium mobaraense transglutaminase by Corynebacterium glutamicum: processing of the pro-transglutaminase by a cosecreted subtilisin-like protease from Streptomyces albogriseolus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:358-366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krämer, R. 1994. Secretion of amino acids by bacteria: physiology and mechanism. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 12:75-94. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuraishi, C., J. Sakamoto, and T. Soeda. 1996. The usefulness of transglutaminase for food processing, p. 29-38. In G. R. Takeoka, R. Teranishi, P. J. Williams, and A. Kobayashi (ed.), Biotechnology for improved foods and flavors. ACS Symposium Series 637. American Chemical Society, Washington, D.C.

- 8.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liebl, W., A. Bayerl, B. Schein, U. Stillner, and K. H. Schleifer. 1989. High efficiency electroporation of intact Corynebacterium glutamicum cells. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 53:299-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liebl, W. 1991. The genus Corynebacterium—nonmedical, p. 1157-1171. In A. Balows, H. G. Trüper, M. Dworkin, W. Harder, and K. H. Schleifer (ed.), The prokaryotes. Springer-Verlag, New York, N.Y.

- 11.Motoki, M., and N. Nio. 1983. Cross-linking between different food proteins by transglutaminase. J. Food Sci. 48:561-566. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noguchi, K., K. Ishikawa, K. Yokoyama, T. Ohtsuka, N. Nio, and E. Suzuki. 2001. Crystal structure of red sea bream transglutaminase. J. Biol. Chem. 276:12055-12059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 14.Suzuki, M., S. Taguchi, S. Yamada, S. Kojima, K. Miura, and H. Momose. 1997. A novel member of the subtilisin-like protease family from Streptomyc albogriseolus. J. Bacteriol. 179:430-438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takehana, S., K. Washizu, K. Ando, S. Koikeda, K. Takeuchi, H. Matsui, M. Motoki, and H. Takagi. 1994. Chemical synthesis of the gene for microbial transglutaminase from Streptoverticillium and its expression in Escherichia coli. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 58:88-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Washizu, K., K. Ando, S. Koikeda, S. Hirose, A. Matsuura, H. Takagi, M. Motoki, and K. Takeuchi. 1994. Molecular cloning of the gene for microbial transglutaminase from Streptoverticillium and its expression in Streptomyces lividans. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 58:82-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yasueda, H., K. Nakanishi, Y. Kawakawa, K. Nagase, M. Motoki, and H. Matsui. 1995. Tissue-type transglutaminase from red sea bream (Paris major): sequence analysis of the coda and functional expression in Escherichia coli. Eur. J. Biochem. 232:411-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yokoyama, K., N. Nakamura, K. Saguaro, and K. Kubota. 2000. Overproduction of microbial transglutaminase in Escherichia coli, in vitro refolding, and characterization of the refolded form. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 64:1263-1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]