Abstract

Anaeromyxobacter dehalogenans strain 2CP-C has been shown to grow by coupling the oxidation of acetate to the reduction of ortho-substituted halophenols, oxygen, nitrate, nitrite, or fumarate. In this study, strain 2CP-C was also found to grow by coupling Fe(III) reduction to the oxidation of acetate, making it one of the few isolates capable of growth by both metal reduction and chlororespiration. Doubling times for growth of 9.2 and 10.2 h were determined for Fe(III) and 2-chlorophenol reduction, respectively. These were determined by using the rate of [14C]acetate uptake into biomass. Fe(III) compounds used by strain 2CP-C include ferric citrate, ferric pyrophosphate, and amorphous ferric oxyhydroxide. The addition of the humic acid analog anthraquinone 2,6-disulfonate (AQDS) increased the reduction rate of amorphous ferric iron oxide, suggesting AQDS was used as an electron shuttle by strain 2CP-C. The addition of chloramphenicol to fumarate-grown cells did not inhibit Fe(III) reduction, indicating that the latter activity is constitutive. In contrast, the addition of chloramphenicol inhibited dechlorination activity, indicating that chlororespiration is inducible. The presence of insoluble Fe(III) oxyhydroxide did not significantly affect dechlorination, whereas the presence of soluble ferric pyrophosphate inhibited dechlorination. With its ability to respire chlorinated organic compounds and metals such as Fe(III), strain 2CP-C is a promising model organism for the study of the interaction of these potentially competing processes in contaminated environments.

Halogenated organic compounds are often recalcitrant and toxic and represent an important class of environmental pollutants (11, 47). Reductive dehalogenation has been considered an important process for the bioremediation of contaminated anaerobic environments containing halogenated compounds (11, 15, 16, 20, 29). Since other alternative electron acceptors are almost always present in the environment with halogenated compounds, potential competing microbial processes should be taken into consideration when chlororespiring bacteria are used for bioremediation. For example, the influence of sulfur and nitrogen oxyanions on dehalogenation has been investigated extensively (8, 13, 41, 42, 46). In contrast, the influence of Fe(III) reduction on reductive dehalogenation has not been thoroughly investigated (23), even though ferric iron is by mass the most important alternative electron acceptor in anaerobic soil and sediment environments (4, 44). Only enrichment culture studies have been done that have shown that dehalogenation does occur when ferric iron is present (18, 30); however, these studies have not established a link between the two processes.

The difficulty in studying the influences of ferric iron and halogenated compounds on microbial physiology is due in part to the lack of pure cultures capable of both halorespiration and dissimilatory Fe(III) reduction. Both halorespiring (chloridogenic) microorganisms and dissimilatory Fe(III) reducers are widely distributed in various environments and among different phylogenetic groups (10, 11, 22, 23, 29). Very few isolates, however, have been reported to reduce both halogenated compounds and ferric iron as electron acceptors (19, 35, 37, 45). Among these chloridogenic isolates, only Desulfuromonas michiganensis (45), Desulfitobacterium dehalogenans, and Desulfitobacterium chlororespirans (35) were reported to actually grow via Fe(III) reduction. The present study presents evidence that the halorespiring Anaeromyxobacter dehalogenans strain 2CP-C is also capable of coupling growth to both dissimilatory Fe(III) reduction and reductive dechlorination. This organism is the first myxobacterium found to be capable of anaerobic respiration, most significantly with the ability to rapidly dehalogenate ortho-substituted halophenols (3, 41). Previously, strain 2CP-C had also been shown to couple acetate oxidation to the reduction of several other electron acceptors such as oxygen, nitrate, nitrite, and fumarate, making it a promising model organism for studying potential interferences between competing substrates that might be important in bioremediation (41). In order to obtain a better understanding of how an organism adapts when both Fe(III) and halogenated compounds are present as electron acceptors, physiological studies were conducted to characterize Fe(III) reduction by strain 2CP-C and the impact of Fe(III) reduction on chlororespiration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strain and culture conditions.

A. dehalogenans strain 2CP-C (ATCC BAA-259) was routinely grown in 160-ml serum bottles with 100 ml of degassed mineral salts medium or in 30-ml anaerobic culture tubes with 20 ml of medium and closed with butyl rubber stoppers and aluminum seals. The mineral salts medium was prepared and handled as previously described (41). Cultures were incubated in the dark at 30°C under anaerobic conditions (100% N2 gas headspace). For routine cultivation, acetate (2 mM) was added as an electron donor and fumarate (5 mM) was added as the electron acceptor. The culture was maintained by transferring 1% (vol/vol) inoculum to fresh medium after fumarate was depleted and growth had ceased. Strict anaerobic techniques were used throughout all of the experimental manipulations.

In experiments testing Fe(III) reduction, cultures were started in 30-ml anaerobic culture tubes or as otherwise stated. A 1% (vol/vol) inoculum of fumarate-grown culture was added to 20-ml anaerobic medium with acetate as the electron donor and one of the following Fe(III) compounds as electron acceptor: ferric citrate (4 mM), ferric pyrophosphate (1.5 mM), or amorphous Fe(III) oxyhydroxide (4 mM). Amorphous Fe(III) oxyhydroxide was prepared as previously described (25). A concentration of 130 μM anthraquinone 2,6-disulfonate (AQDS) was used if added. Controls were prepared without the addition of electron donor or cells.

Monitoring of growth via [14C]acetate assimilation.

Cultures were initiated by transferring a 1% (vol/vol) inoculum to 100-ml mineral salts medium from fumarate-grown cultures. Methyl-labeled [14C]acetate was added together with nonlabeled acetate to a total concentration of 1 mM as the only electron donor and carbon source from degassed sterile stock solutions. The final specific activities of the acetate in the media were 2 × 108 dpm (90.1 μCi) and 3.6 × 107 dpm (16.2 μCi) per mmol of acetate for experiments with 2-chlorophenol (2-CP) and Fe(III), respectively. Ferric citrate (3 mM) or 2-CP (150 μM) was added as an electron acceptor to the culture. Control cultures were established by omitting either electron acceptor or biomass.

Samples were taken periodically for the analysis of 14C assimilation into biomass, acetate, Fe(II), and/or phenol. The [14C]acetate assimilated into cells was quantified by taking 0.5 ml of culture suspension and filtering it through a Millipore 0.2-μm (pore-size) cellulose membrane filter. The filter was rinsed with 20 ml of distilled deionized water and then placed in a scintillation vial with 5 ml of a biodegradable scintillation cocktail. After the filter dissolved, the 14C radioactivity associated with it was determined by scintillation counting. Because acetate was the sole carbon source added into the medium, the amount of [14C]acetate assimilated is a direct measure of cell yield, and the rate of assimilation is a direct measure of growth rate.

To convert the [14C]acetate assimilated as disintegrations per minute/milliliter to total cell mass synthesized as milligrams/liter, the empirical formula for biomass of C5H7O2N was used (40). Based on the balance of electron equivalents, the stoichiometry for cell synthesis was 0.40 mmol of cell mass per mmol of acetate assimilated when acetate was used as the electron donor and carbon source (40).

|

Thus, the cell synthesis during Fe(III) reduction was calculated as follows:

|

Doubling times of strain 2CP-C growing by Fe(III) reduction and chloridogenesis were determined from the increase in 14C-labeled cell mass during log-phase growth.

Analytical methods.

2-CP and other phenolic compounds were analyzed on a Hewlett-Packard 1090 high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) apparatus with a Chemstation analysis software package and a Bio-Rad Hi-Pore reversed-phase column as previously described (41). Peaks were quantified at 218 nm, and concentrations were determined by using known standards. Samples (1 ml) from the cultures were made basic with 10 μl of 2 N sodium hydroxide and filtered through 0.20-μm filters prior to HPLC analysis. Acetate and other volatile fatty acids were analyzed as previously described (41) by using a Waters HPLC apparatus with a Bio-Rad Aminex HPX-87H ion exclusion column heated to 60°C with 0.005 N sulfuric acid as the eluent. Fe(II) in the samples was analyzed by using the HCl extraction ferrozine assay as previously described (26, 27).

Determination of fe and fs values.

The fe value is the fraction of electrons from the electron donor used for energy and accounted for by electron acceptor reduction (5, 31), and fs is the fraction of electrons from the electron donor incorporated into biomass. Since acetate is both the energy source and the carbon source, all of the electrons assimilated into cell mass and used for electron acceptor reduction are derived from acetate. Electrons from acetate were calculated as electron equivalents generated in the complete oxidation to CO2 (8e−/acetate).

fe was determined graphically by plotting the total electron equivalents consumed (acetate) versus the electron equivalents required for the reduction of electron acceptor (ferric iron or 2-CP). The value of fe was then derived from the slope of the regression line. Similarly, fs was determined by plotting electron equivalents of acetate assimilated into cell mass against the total electron equivalents released as acetate consumed. The slope of the regression line then indicates the fs value. The stoichiometry of cell biosynthesis associated with substrate utilization was calculated from the electron balance (40).

Impact of alternative electron acceptors on chloridogenesis and Fe(III) reduction.

Since Fe(III) could be an important electron acceptor in anoxic environments contaminated with chlorinated compounds, the impact of Fe(III) on reductive dechlorination was investigated. 2-CP (130 μM) was added, together with 4 mM amorphous Fe(III) oxyhydroxide or 1.8 mM ferric pyrophosphate. Cultures were started with a 1% inoculum from a fumarate-grown culture. Both dechlorination and Fe(III) reduction were monitored.

Inhibition study by chloramphenicol.

To determine whether Fe(III) or 2-CP reduction activities were constitutive, the protein synthesis inhibitor chloramphenicol was used (36). An anaerobic sterile stock solution of chloramphenicol in ethanol (50 mM) was prepared by filtering through a 0.2-μm (pore-size) filter. Noninduced dense cultures (20 ml) were pregrown to late log phase on 5 mM fumarate with excess acetate in 30-ml anaerobic tubes. Rates of dechlorination or Fe(III) reduction were measured after the addition of 150 μM 2,6-dichlorophenol (2,6-DCP) or 0.5 mM ferric pyrophosphate to cultures with or without chloramphenicol (300 μM). The cell concentration after the addition of substrate remained constant, as indicated by an optical density measured at 600 nm of 0.12.

Chemicals.

2-CP, 2,6-DCP, ferric citrate, ferric pyrophosphate, AQDS, and chloramphenicol were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo.

RESULTS

Anoxic growth coupled to Fe(III) and CP reduction.

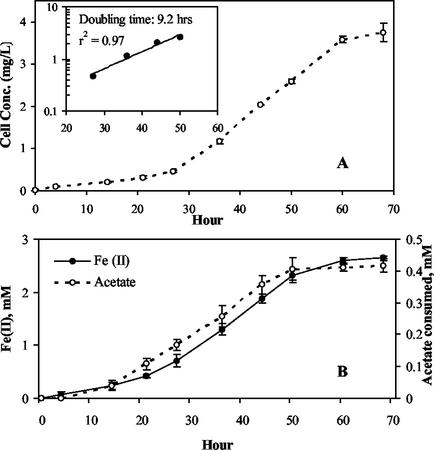

A. dehalogenans strain 2CP-C grew by using Fe(III) reduction as the increase in 14C-labeled biomass was coincident with increase in ferrous iron [Fe(II)] and acetate consumption (Fig. 1). No intermediate products were detected in the medium during acetate oxidation, and citrate was not used as an electron donor in controls without added acetate (data not shown). Similarly, [14C]acetate uptake into biomass increased with the simultaneous dechlorination of 2-CP (Fig. 2). The sensitivity of [14C]acetate assimilation allowed the accurate detection of small incremental increases in biomass in cultures with no visible cell yields. This was particularly useful with cultures grown on 2-CP, since no visible growth was observed.

FIG. 1.

Coupling of growth of strain 2CP-C to Fe(III) reduction. (A) Increase in biomass concentration derived from [14C]acetate incorporated into new cells. (B) Coincidental reduction of Fe(III) citrate and acetate oxidation during growth. Data are averaged from duplicate cultures, with error bars showing the standard deviation. The inset plot shows the doubling time of cells during exponential growth.

FIG. 2.

Coupling of cell growth to 2-CP dechlorination and coincidental appearance of phenol. Cell concentration is derived from [14C]acetate incorporated into biomass. Data are averaged from duplicate cultures, with error bars showing the standard deviation. The inset plot shows doubling time of cells during exponential growth.

Doubling times of 9.2 and 10.2 h were measured for growth coupled to Fe(III) reduction and chloridogenesis, respectively. Graphically, fe and fs were determined for ferric iron reduction (fe = 0.80 and fs = 0.22) and chlororespiration (fe = 0.66 and fs = 0.34) (Fig. 3). All of the electrons from the electron donor were accounted for (fe + fs ≈ 1). The results of a second experiment without [14C]acetate verified the electron balance obtained for iron-reducing conditions with a calculated fe of 0.78 (data not shown). The complete stoichiometry of Fe(III) reduction coupled to growth can be determined from the electron balance (40). Using C5H7O2N as the empirical formula for cell mass, the following stoichiometry was obtained:

|

The stoichiometry for chloridogenesis from 2-CP was:

|

From these reactions, the growth yields were calculated as 9.0 and 15.4 g of cells per mol of acetate for Fe(III) and 2-CP reduction, respectively.

FIG. 3.

Graphical determination of fe and fs for strain 2CP-C in Fe(III) citrate-reducing culture (A) and 2-CP respiring cells (B), as indicated by the slope of the regression line. Reducing equivalents from acetate are plotted as electron equivalents ([H]) generated in the complete oxidation to CO2. Reducing equivalents for energy formation are plotted as [H] consumed in the reduction of Fe(III) to Fe(II) or 2-CP to phenol. Reducing equivalents for biosynthesis are also plotted as [H] incorporated into biomass. The data are averaged from duplicate cultures, with error bars showing the standard deviation.

Reduction of amorphous Fe(III) oxyhydroxide.

Amorphous Fe(III) oxyhydroxide is one of the more abundant forms of ferric iron oxide in nature (44), and thus it was important to test strain 2CP-C's ability to grow with this compound as an electron acceptor. Amorphous Fe(III) oxyhydroxide was reduced rapidly at the expense of acetate oxidation (Fig. 4A). Abiotic reduction of Fe(III) did not occur in controls without cells or added electron donor. In all experiments with amorphous ferric oxyhydroxide, acetate concentrations decreased except in the control (data not shown). This indicated that acetate oxidation was linked to Fe(III) reduction.

FIG. 4.

Reduction of ferric iron by strain 2-CPC in the presence or absence of AQDS. The reduction of amorphous Fe(III) oxyhydroxide (4 mM) (A) and the reduction of ferric citrate (B) are indicated by the increase in ferric iron concentration. The results are averages of duplicate cultures, with error bars showing the standard deviation. The absence of a bar indicates that the standard deviation was smaller than the symbol. Control A contained iron, acetate, and AQDS, but not biomass; control B contained iron, AQDS, and biomass, but no acetate.

Humic acids are directly involved in both oxidation and reduction of iron in the environment, essentially acting as electron shuttles. The humic acid analog AQDS was tested as a potential electron shuttle between strain 2CP-C and amorphous Fe(III) oxyhydroxide. In the presence of 130 μM AQDS, a significant increase in the Fe(III) reduction rates were observed, suggesting that in the absence of an electron shuttle the reaction rate was limited by the availability of Fe(III) (Fig. 4A). In comparison, the rate of ferric citrate reduction was not significantly altered by the presence of AQDS (Fig. 4B), indicating that this soluble form of Fe(III) was not limiting and could freely diffuse to the cell surface.

Interactions between Fe(III) reduction and chlororespiration.

The influence of Fe(III) reduction on reductive dechlorination was tested by using both soluble and insoluble Fe(III) forms. The presence of soluble ferric pyrophosphate inhibited initial dechlorination of 2-CP, whereas the presence of amorphous Fe(III) oxyhydroxide only slightly delayed dechlorination of 2-CP (Fig. 5 and 6). In the latter case, amorphous Fe(III) oxyhydroxide reduction and dechlorination occurred simultaneously. In contrast, rapid dechlorination occurred only after complete reduction of Fe(III) pyrophosphate, suggesting that dechlorination was inhibited by the presence of soluble Fe(III) species but not the presence of insoluble Fe(III) species. The reduction of both soluble and insoluble Fe(III) species were not affected by the presence of 2-CP (Fig. 6).

FIG. 5.

Dechlorination of 2-CP in the presence of ferric pyrophosphate (A) and amorphous Fe(III) oxyhydroxide (B). The results are the averages of duplicate cultures, with error bars indicating the standard deviation.

FIG. 6.

Influence of 2-CP on Fe(III) reduction, as shown by increase in ferrous iron, Fe(II) (A), and influence of Fe(III) on 2-CP dechlorination, as indicated by the disappearance of 2-CP (B). Ferric compounds tested are Fe(III) pyrophosphate or amorphous Fe(III) oxihydroxide. The data are averages of duplicate cultures.

Effect of chloramphenicol on Fe(III) reduction and dechlorination.

The ability of strain 2CP-C to constitutively reduce Fe(III) and dechlorinate 2-CP was tested by adding chloramphenicol to dense fumarate-grown cultures. Chloramphenicol was used as an inhibitor of de novo protein biosynthesis. Thus, a nonconstitutive activity would be much lower in the presence of chloramphenicol than in its absence. Fe(III) reduction activity appeared to be constitutive since the background reduction rate was identical to the reduction rate in the absence of chloramphenicol. Iron reduction was also immediate in nitrate-grown cultures, which confirmed the constitutive nature of this activity. In contrast, results showed that dechlorination of 2,6-DCP was induced, since the background dechlorination rate was much lower than the rate without chloramphenicol (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Effect of chloramphenicol on the reduction of 2,6-DCP (A) and Fe(III) pyrophosphate (B). Reductive dechlorination was monitored as the depletion of 2,6-DCP, and reduction of Fe(III) was indicated by the increase in Fe(II) concentration. Noninduced resting cells were obtained by growing strain 2CP-C on fumarate and acetate. Cultures were fed 150 μM 2,6-DCP or 0.5 mM Fe(III) pyrophosphate to test or induce activity. In addition, inhibited cultures were amended with 300 μM chloramphenicol. The data are averaged from triplicate cultures, with error bars showing the standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

A. dehalogenans is shown to couple growth directly to dissimilatory reduction of ferric iron, adding to the increasing list of such organisms isolated from the environment. In contrast to previous studies with Fe(III)-reducing bacteria, growth rates were measured by using the rate of 14C assimilation from radiolabeled acetate. This made it easy to compare the measured growth rates with those obtained when growing A. dehalogenans under chlororespiring conditions with 2-CP. Previous studies have relied primarily on direct microscopic cell counts for monitoring the growth of dissimilatory Fe(III)-reducing and halorespiring microorganisms (6, 12, 27, 33). The successful use of direct counts is limited, the quantification of biomass is not very precise (28), and it requires a fairly high concentration of cells. Our experiments demonstrate that 14C assimilation is an accurate, sensitive, and more quantitative method for measuring growth rates, particularly when low substrate concentrations are used. Growth experiments in the present study were conducted with very low initial and final biomass concentrations, with virtually no detectable turbidity, and yet the assimilation of 14C into biomass made it easy to quantitatively measure growth even though there was no visible change in cell density. The need to use low substrate conditions may be particularly relevant when studying microbial growth and behavior under normal environmental conditions. For example, since halogenated compounds are toxic, only low concentrations of 2-CP (150 μM) are added to the A. dehalogenans culture, thus yielding only a small increase in cell mass.

In addition to measuring the growth rates under both iron-reducing and chloridogenic conditions, a complete electron balance for each respiratory process was obtained. With Fe(III) reduction, the electron balance had not been previously reported since the widely used method of direct cell count does not accurately quantify biomass increase. Under Fe(III)-reducing conditions, an fe and fs of 0.80 and 0.22, respectively, are quantitatively established for strain 2CP-C. The calculated growth yield of 1.4 g of cells per mol of Fe(III) reduced is higher than the yield of 0.56 g of cells per mol of Fe(III) reduced reported for Geobacter metallireducens strain GS-15 but lower than the yields of 4.8 to 19.6 g cells per mol of Fe(III) reported for Shewanella putrefaciens strain MR-1 (2, 32). In the case of Shewanella, growth yields for Fe(III) reduction were also found to be dependent on the growth conditions used (32). From our study it is not clear whether the growth conditions used for culturing A. dehalogenans will impact growth yields obtained during dissimilatory Fe(III) reduction, and this warrants further investigation.

One interesting aspect of the electron balance measurements is the unexpected higher cell yield from chloridogenesis compared to ferric iron reduction, with fs values of 0.34 versus 0.22, respectively. The fe value of 0.66 measured for respiration of 2-CP by A. dehalogenans is consistent with the values reported in other studies (21, 41), suggesting a fundamental physiological difference between the two processes. Despite the apparent higher energy released from Fe(III) reduction inferred from redox potentials at neutral pH (the E0′ is 0.77 V for Fe3+/Fe2+ and 0.40 V for 2-CP/phenol) (9, 28), strain 2CP-C appears to be less efficient in coupling biosynthesis to Fe(III) reduction than to reductive dechlorination. A consequence of the lower growth yield (fs) and slightly faster growth rate under Fe(III)-reducing conditions is a higher substrate turnover rate than that obtained with chlororespiration by strain A. dehalogenans.

The ability of strain 2CP-C to reduce amorphous Fe(III) oxyhydroxide has practical implications since amorphous Fe(III) oxyhydroxide is considered one of the most common ferric iron oxides in nature and not all Fe(III) reducers are capable of reducing the poorly soluble amorphous Fe(III) oxyhydroxide. The ability of strain 2CP-C to reduce amorphous Fe(III) oxyhydroxide suggests it could have a potential ecological role in iron cycling in natural environments. Recently, Petrie et al. (L. Petrie, N. N. North, S. L. Dollhopf, D. L. Balkwill, and J. E. Kostka, submitted for publication) showed that this appears to be the case. Based on 16S ribosomal DNA sequences of most-probable-number analysis, these authors determined that Anaeromyxobacter species were the predominant ferric iron-reducing organisms in contaminated groundwater sediments. Also, as with the Geobacteriaceae, the reduction of amorphous Fe(III) oxyhydroxide by strain 2CP-C was accelerated by the presence of a very low concentration of AQDS (24). The role of the humic acid analog AQDS as an electron shuttle has been demonstrated previously and thought to provide a strategy for Fe(III) reducers to access insoluble Fe(III) compounds (24). The ability to employ this strategy suggests strain 2CP-C is well suited to the lifestyle of Fe(III) reduction in natural environments, where natural electron shuttles may be present.

The importance of Fe(III) respiration for strain 2CP-C is further supported by its constitutive nature (Fig. 7). Both constitutive and inducible Fe(III) reduction activities have been found in several dissimilatory Fe(III)-reducing bacteria; however, no consistent pattern of regulation has been reported (1, 17, 34). Nevertheless, its constitutive ability to grow using Fe(III) reduction allows this strain to grow readily in anaerobic environments where Fe(III) is available. This may also explain the observation that strain 2CP-C grows slightly faster with Fe(III) than with 2-CP, a substrate that requires induction (14), as an electron acceptor.

Another trait of strain 2CP-C that might also contribute to its adaptation to Fe(III) respiration is its ability to grow microaerophilically (41). With the ability to live at the oxic-anoxic interface, strain 2CP-C would be able to thrive in an environment where iron cycling is considered to be significant. The gliding motility found in myxobacteria and A. dehalogenans could also potentially aid their ability to maneuver in this zone and to contact the Fe(III) oxide surfaces.

The ability of A. dehalogenans to grow by both ferric iron reduction and chloridogenesis makes it one of the few isolates reported able to do so (19, 35, 45). Notably, in our experiments reductive dechlorination and reduction of amorphous Fe(III) oxyhydroxide occur simultaneously (Fig. 5), indicating dechlorination would not be inhibited by the Fe(III) in natural environments. Admittedly, this greatly depends on the form of Fe(III) present, since ferric pyrophosphate does inhibit dechlorination until iron reduction is complete. The ability to express both types of activities is desirable for bioremediation of contaminated sites, since Fe(III) and other competing electron acceptors are commonly found where halogenated compounds occur.

A. dehalogenans strain 2CP-C is the first member of myxobacteria capable of anaerobic growth (41) and now is the first strain shown to grow by reducing Fe(III). The discovery of Fe(III)-reducing myxobacteria, however, is not completely unexpected since the 16S rRNA-based phylogeny groups them within the δ-subdivision of the Proteobacteria (7, 38, 39). This group contains many organisms capable of Fe(III) reduction, such as the Geobacteriaceae. It is also not surprising since it has been suggested that aerobic myxobacteria probably represent adaptations of ancestral anaerobic populations to oxygenic environments (22, 43, 48).

The discovery of Fe(III)-reducing myxobacteria also gives some insights into the common observation that phenotype and phylogeny often appear to disagree. One proposed explanation of this observation is that microorganisms are usually studied from different perspectives and that one phenotypic characteristic studied in detail in one organism may never be investigated in another (48). This was truly the case with A. dehalogenans strains until the present study, which were isolated for their ability to respire chlorinated aromatic compounds (41). The physiological trait of Fe(III) reduction provides a unifying phenotype between myxobacteria and other anaerobic branches of δ-Proteobacteria. Indeed, it is possible that some of the well-characterized aerobic myxobacteria may also be capable of anaerobic respiration.

With the flexibility to respire a broad range of electron acceptors, A. dehalogenans or other Anaeromyxobacter strains are promising model organisms for studying the competition between chlororespiration and other respiratory processes [e.g., Fe(III) reduction], which may be encountered in contaminated or even natural settings. Basic research in this area could potentially lead to strategies that could be used to bioremediate sites with mixed organic and metal contaminants.

Acknowledgments

We thank Joanne Chee-Sanford for initially reviewing the manuscript and for providing valuable suggestions on how to improve it.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnold, R. G., T. J. DiChristina, and M. R. Hoffmann. 1986. Inhibitor studies of dissimilative Fe(III) reduction by Pseudomonas sp. strain 200 (“Pseudomonas ferrireductans”). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 52:282-289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Champine, J. E., B. Underhill, J. M. Johnston, W. W. Lilly, and S. Goodwin. 2000. Electron transfer in the dissimilatory iron-reducing bacterium Geobacter metallireducens. Anaerobe 6:187-196. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cole, J. R., A. L. Cascarelli, W. W. Mohn, and J. M. Tiedje. 1994. Isolation and characterization of a novel bacterium growing via reductive dechlorination of 2-chlorophenol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:3536-3542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cornell, R. M., and U. Schwertmann. 1996. The iron oxides—structure, properties, reactions, occurrence, and uses. VCH, Weinheim, Germany.

- 5.Criddle, C. S., L. M. Alvarez, and P. L. McCarty. 1991. Microbial processes in porous media, p. 641-691. In J. Bear and M. Y. Corapcioglu (ed.), Transport processes in porous media. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- 6.Cummings, D. E., F. Caccavo, Jr., S. Spring, and R. F. Rosenzweig. 1999. Ferribacterium limneticum, gen. nov., sp. nov., an Fe(III)-reducing microorganism isolated from mining-impacted freshwater lake sediment. Arch. Microbiol. 171:183-188. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dawid, W. 2000. Biology and global distribution of myxobacteria in soils. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 24:403-427. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.DeWeerd, K. A., and J. M. Suflita. 1990. Anaerobic aryl reductive dehalogenation of halobenzoates by cell extracts of Desulfomonile tiedjei. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:2999-3005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dolfing, J., and B. K. Harrison. 1992. Gibbs free energy of formation of halogenated aromatic compounds and their potential role as electron acceptors in anaerobic environments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 26:2213-2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El Fantroussi, S., H. Naveau, and S. N. Agathos. 1998. Anaerobic dechlorinating bacteria. Biotechnol. Prog. 14:167-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fetzner, S. 1998. Bacterial dehalogenation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 50:633-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Francis, C., A., A. Y. Obraztsova, and B. M. Tebo. 2000. Dissimilatory metal reduction by the facultative anaerobe Pantoea agglomerans SP1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:543-548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerritse, J., O. Drzyzga, G. Kloetstra, M. Keijmel, L. P. Wiersum, R. Hutson, M. D. Collins, and J. C. Gottschal. 1999. Influence of different electron donors and acceptors on dehalorespiration of tetrachloroethene by Desulfitobacterium frappieri TCE1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:5212-5221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He, Q., and R. A. Sanford. 2002. Induction characteristics of reductive dehalogenation in the ortho-halophenol-respiring bacterium, Anaeromyxobacter dehalogenans. Biodegradation 13:307-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holliger, C., and W. Schumacher. 1994. Reductive dehalogenation as a respiratory process. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 66:239-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holliger, C., G. Wohlfarth, and G. Diekert. 1999. Reductive dechlorination in the energy metabolism of anaerobic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 22:383-398. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson, D. B., and T. A. M. Bridge. 2002. Reduction of ferric iron by acidophilic heterotrophic bacteria: evidence for constitutive and inducible enzyme systems in Acidiphilium spp. J. Appl. Microbiol. 92:315-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kazumi, J., M. M. Häggblom, and L. Y. Young. 1995. Degradation of monochlorinated and nonchlorinated aromatic compounds under iron-reducing conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:4069-4073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krumholz, L. R., R. Sharp, and S. S. Fishbain. 1996. A freshwater anaerobe coupling acetate oxidation to tetrachloroethylene dehalogenation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:4108-4113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee, M. D., J. M. Odom, and R. J. Buchanan. 1998. New perspectives on microbial dehalogenation of chlorinated solvents: insights from the field. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 52:423-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Löffler, F. E., J. M. Tiedje, and R. A. Sanford. 1999. Fraction of electrons consumed in electron acceptor reduction and hydrogen thresholds as indicators of halorespiratory physiology. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:4049-4056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lonergan, D. J., H. L. Jenter, J. D. Coates, E. J. P. Phillips, T. M. Schmidt, and D. R. Lovley. 1996. Phylogenetic analysis of dissimilatory Fe(III)-reducing bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 178:2402-2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lovley, D. R. 1997. Microbial Fe(III) reduction in subsurface environments. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 20:305-313. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lovley, D. R., J. D. Coates, E. L. Blunt-Harris, E. J. P. Phillips, and J. C. Woodward. 1996. Humic substances as electron acceptors for microbial respiration. Nature 382:445-448. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lovley, D. R., and E. J. P. Phillips. 1986. Organic matter mineralization with reduction of ferric iron in anaerobic sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 51:683-689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lovley, D. R., and E. J. P. Phillips. 1986. Availability of ferric iron for microbial reduction in bottom sediments of the freshwater tidal Potomac River. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 52:751-757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lovley, D. R., and E. J. P. Phillips. 1988. Novel mode of microbial energy metabolism: organic carbon oxidation coupled to dissimilatory reduction of iron or manganese. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 54:1472-1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Madigan, M. T., J. M. Martinko, and J. Parker. 2000. Brock biology of microorganisms, 9th ed. Prentice-Hall, Inc., Upper Saddle River, N.J.

- 29.Mohn, W. W., and J. M. Tiedje. 1992. Microbial reductive dehalogenation. Microbiol. Rev. 56:482-507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Monserrate, E., and M. M. Häggblom. 1997. Dehalogenation and biodegradation of brominated phenols and benzoic acids under iron-reducing, sulfidogenic and methanogenic conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3911-3915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCarty, P. L. 1971. Energetics and bacterial growth, p. 495-531. In J. Faust and J. V. Hunter (ed.), Organic compounds in aquatic environments. Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 32.Myers, C. R., and J. M. Myers. 1994. Ferric iron reduction-linked growth yields of Shewanella putrifaciens MR-1. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 76:253-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Myers, C. R., and K. H. Nealson. 1988. Bacterial manganese reduction and growth with manganese oxide as the sole electron acceptor. Science 240:1319-1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Myers, C. R., and K. H. Nealson. 1990. Respiration-linked proton translocation coupled to anaerobic reduction of manganese(IV) and iron(III) in Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1. J. Bacteriol. 172:6232-6238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niggemyer, A., S. Spring, E. Stackebrandt, and R. F. Rosenzweig. 2001. Isolation and characterization of a novel As(V)-reducing bacterium: implication for arsenic mobilization and the genus Desulfitobacterium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:5568-5580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pestka, S. 1975. Chloramphenicol. Antibiotics 3:370-395. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Picardal, F. W., R. G. Arnold, H. Couch, A. M. Little, and M. E. Smith. 1993. Involvement of cytochromes in the anaerobic biotransformation of tetrachloromethane by Shewanella putrefaciens 200. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:3763-3770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reichenbach, H. 1993. Biology of the myxobacteria: ecology and taxonomy, p. 13-62. In M. Dworkin and D. Kaiser (ed.), Myxobacteria II. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 39.Reichenbach, H., and M. Dworkin. 1992. The myxobacteria, p. 3416-3487. In A. Balows, H. G. Trüper, M. Dworkin, W. Harder, and K. H. Schleifer (ed.), The prokaryotes, 2nd ed. Springer-Verlag, New York, N.Y.

- 40.Rittmann, B. E., and P. L. McCarty. 2001. Environmental biotechnology: principles and applications. McGraw-Hill, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 41.Sanford, R. A., J. R. Cole, and J. M. Tiedje. 2002. Characterization and description of Anaeromyxobacter dehalogenans gen. nov., sp. nov., an aryl-halorespiring facultative anaerobic myxobacterium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:893-900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanford, R. A., and J. M. Tiedje. 1997. Chlorophenol dechlorination and subsequent degradation in denitrifying microcosms fed low concentrations of nitrate. Biodegradation 7:425-434. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shimkets, L., and C. R. Woese. 1992. A phylogenetic analysis of the myxobacteria: basis for their classification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:9459-9463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Straub, K. L., M. Benz, and B. Schink. 2001. Iron metabolism in anoxic environments at near neutral pH. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 34:181-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sung, Y., K. M. Ritalahti, R. A. Sanford, J. W. Urbance, S. J. Flynn, J. M. Tiedje, and F. E. Löffler. Characterization of two tetrachloroethene-reducing, acetate-oxidizing anaerobic bacteria and their description as Desulfuromonas michiganensis sp. nov. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:2964-2974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Townsend, G. T., and J. M. Suflita. 1997. Influence of sulfur oxyanions on reductive dehalogenation activities in Desulfomonile tiedjei. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3594-3599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vogel, T. M., C. S. Criddle, and P. L. McCarty. 1987. Transformation of halogenated aliphatic compounds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 21:722-736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Woese, C. R. 1987. Bacterial evolution. Microbiol. Rev. 51:221-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]