Abstract

Multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains of Salmonella enterica serotype Newport have been described for many years. However, the recognition of Newport strains with resistance to cephalosporin antibiotics is more recent. Plasmid-mediated CMY-2 AmpC β-lactamases have been identified in Salmonella in the United States, and the blaCMY-2 gene has been shown to be present in Salmonella serotype Newport. This organism is currently undergoing epidemic spread in both animals and humans in the United States, and this is to our knowledge the first description of the molecular epidemiology of this Salmonella strain in animals. Forty-two isolates were included in this study. All isolates were characterized by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, plasmid analysis, and antibiogram. Four pulsed-field profiles with XbaI were observed. Plasmid analyses showed that although the majority of isolates harbored a single plasmid of 140 kb, this plasmid was not identical in all strains. All isolates showed the presence of the blaCMY gene by PCR. Integrons were detected in 16 of the 42 isolates; a fragment of approximately 1,000 bp, amplified with the intI-F and aadAI-R primers, confirmed the presence of the aadAI gene cassette within an integron in these 16 isolates. The potential for coselection of the blaCMY gene, if located on an MDR replicon, may not be dependent on any particular antibiotic but rather may be the result of more general antimicrobial use. If this replicon is mobile, it is to be expected that similar MDR strains of additional Salmonella serotypes will be recognized in due course.

Outbreaks of human and animal disease due to Salmonella enterica serotype Newport have been described in the literature for the past 3 decades. Salmonella serotype Newport has been isolated from food sources such as potato salad (11), hamburger (7, 26), chicken (1), precooked roast beef (24), ham or pork (13, 16), fish and seafood (10), and alfalfa sprouts (29, 30). In the United States, serotype Newport has been implicated in several large outbreaks of human salmonellosis, and this serotype is consistently among the top 10 salmonella serotypes isolated from human infection. In addition to its role in food-borne disease outbreaks, serotype Newport has also been implicated in outbreaks on dairy farms (3, 21) and in horses (14, 28).

Multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains of serotype Newport have been described for many years, but more recently, MDR serotype Newport strains with resistance to cephalosporins have been described (5, 31). The antibiogram of a single isolate of serotype Newport described by Winokur and colleagues was consistent with expression of an AmpC enzyme (31). The ampC gene, termed CMY-2, was encoded on a nonconjugative but transferable plasmid. Resistance to chloramphenicol (CHL), sulfamethoxazole (SUL), tetracycline (TET), and possibly streptomycin (STR) cotransferred with the ampC gene and was taken to indicate that the plasmid was responsible for the MDR phenotype observed in this strain. It was also shown that the MDR plasmid described above contained one or more integrons, but there was no evidence to suggest that the CMY-2 gene was present as a gene cassette (31).

Characterization of the CMY-2 β-lactamase responsible for cephamycin resistance was first achieved by Bauernfeind and colleagues in 1996 with a cefoxitin-resistant strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated in 1990 from a urine sample from a young man in Athens, Greece (2). Resistance to cephamycins in gram-negative organisms is widespread in those genera or species that carry chromosomal ampC genes (2). The activity of these chromosomal AmpC enzymes is not inhibited by clavulanate, sublactam, and tazobactam. Therefore, resistance to cephamycins and inactivity of β-lactamase inhibitors have usually been established as an indicator of the chromosomal location of the bla gene. This observation may have contributed to obscuring and postponing the detection of plasmid-mediated cephamycinases (2).

In July 2000, the Salmonella Reference Center (SRC) at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine confirmed that an isolate submitted from the animal diagnostic laboratory at the Pennsylvania State University was an MDR strain of Salmonella serotype Newport that was resistant to cephalosporins. Concurrently, the SRC received a series of bovine isolates from the Maryland Department of Agriculture. These were from a single farm that experienced a significant outbreak of clinical salmonellosis in periparturient dairy cows. Since that time, SRC has received isolates of MDR serotype Newport from 35 different sources.

This study presents the results obtained from phenotypic and genotypic analysis of 42 MDR Salmonella serotype Newport isolates obtained from these 35 different sources.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Bacterial strains used in the study had been submitted to the SRC for confirmation of serotype during the period from July 2000 to August 2001. Pennsylvania isolates were submitted to the SRC via the Pennsylvania Animal Diagnostic Laboratory System (PADLS) from the microbiology laboratories at the New Bolton Center (NBC) of the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, The Pennsylvania State University (PSU), and the Pennsylvania Veterinary Laboratory in Harrisburg (PADLS-H). Additional isolates were submitted from the Maryland Department of Agriculture.

Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 was used as a susceptible control strain in disk diffusion analysis. S. enterica serotype Typhimurium DT104 strain s/921032 was used as a control strain in the integron, plasmid, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) analyses.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

All isolates submitted to the SRC were routinely screened for resistance to 12 antimicrobials by the disk diffusion method (19). The following antimicrobials were tested: ampicillin (AMP) (10 μg/ml), CHL (30 μg/ml), furazolidone (100 μg/ml), gentamicin (GEN) (10 μg/ml), kanamycin (KAN) (30 μg/ml), nalidixic acid (30 μg/ml), ciprofloxacin (5 μg/ml), spectinomycin (SPT) (100 μg/ml), STR (10 μg/ml), TET (30 μg/ml), trimethoprim-SUL (1.25 and 23.75 μg/ml), and tobramycin (10 μg/ml). In addition, susceptibilities to sulfamethazole (25 μg/ml), cephalothin (CEF) (30 μg/ml), ceftiofur (XNL) (30 μg/ml), and ceftriaxone (CRO) (30 μg/ml) were tested by the same method.

Plasmid analysis.

Plasmid profiles and restriction enzyme fragmentation patterns (REFPs) were obtained as previously described (22). Plasmid DNA was examined in crude lysates, and the molecular weights of plasmids were determined by reference to the following plasmids of known size: Rts 1, 180 kb; RA-1, 127 kb; R1, 93 kb; R702, 69 kb; and RP4, 54 kb. A supercoiled DNA ladder (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.) was used for the estimation of molecular weights of small plasmids (<16 kb). The plasmid size values incorporated into plasmid profiles were determined on a minimum of two occasions.

Restriction enzymes were obtained from Life Technologies and were used in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Agarose gels (0.8%) were run in TBE buffer (89 mM Trizma base, 89 mM boric acid, 1.25 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) that contained ethidium bromide, the fragments were visualized on an UV transilluminator and photographed with a Kodak EDAS120 (Life Technologies) digital camera system, and the photographs were stored as digital image files for further analysis.

PFGE.

Whole-cell DNA was prepared in agarose plugs as described previously (20). One-quarter of each agarose plug was equilibrated in restriction enzyme buffer for 1 h at room temperature, and the total DNA was cleaved with the restriction enzyme XbaI at 37°C. For complete digestion of DNA, 20 U of XbaI was used. PFGE was performed at 14°C by the contour-clamped homogeneous electric field method on a CHEF DRII system (Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.) at 6.0 V/cm in 0.5× TBE buffer for 20 h with pulse times of 5 to 50 s. A DNA molecular weight standard (bacteriophage λ concatemers; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) was included on each gel. After electrophoresis, the gel was stained in ethidium bromide for 30 min and then destained in distilled water for 1 h. DNA fragments were visualized and photographed as detailed above.

BioNumerics software (Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium) was used to compare the PFGE profiles.

PCR detection of integrons and gene cassettes.

Detection of integrons and antibiotic gene cassettes was performed as previously described (25). The strains were tested for the int1 and aadA1 genes (25).

Detection of the blaCMY gene.

PCR was performed as previously described (15) and was expected to generate a product of approximately 630 bp.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows details of the 42 strains studied and the results obtained. Each source was numbered from 1 to 35, and isolates from the same sources were included when phenotypic or genotypic differences were observed. Isolates were obtained from bovine (34 isolates), equine (5 isolates), porcine (1 isolate), canine (1 isolate), and avian (1 isolate) species. No isolates were obtained from poultry in this study. The majority of isolates were derived from sources in Pennsylvania; however, four isolates were obtained from a single source in Maryland, and one isolate was obtained from (each) New Jersey and New York.

TABLE 1.

Details of Salmonella serotype Newport isolates in the studya

| SRC no. | Submission date (mo/day/yr) | Code | Species | Source no. | County | Resistance pattern | Plasmid profile (kb) | PFP | Integron size (bp) | Gene cassette |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0007-33 | 07/12/00 | PSU | Bovine | 1 | Mifflin | AMP CHL TET STR SUL CEF XNL | 140 | 1 | None detected | |

| 0007-340 | 07/18/00 | MDAg | Bovine | 2 | Kent | AMP CHL TET STR SUL CEF XNL | 140 | 1 | None detected | |

| 0007-392 | 07/26/00 | MDAg | Bovine | 2 | Kent | AMP CHL TET STR SUL SPT GEN KAN CEF XNL | 140 | 1 | 1,000 | aadA1 |

| 0007-394 | 07/26/00 | MDAg | Bovine | 2 | Kent | AMP CHL TET STR SUL CEF XNL | 140; 100 | 1 | None detected | |

| 0008-122 | 08/04/02 | PADLS-H | Porcine | 3 | Perry | AMP CHL TET STR SUL SPT GEN CEF XNL | 150; 140 | 3 | 1,000 | aadA1 |

| 0008-254 | 08/17/00 | PADLS-H | Bovine | 4 | Franklin | AMP CHL TET STR SUL SPT GEN KAN CEF XNL | 140; 7.5 | 5 | 1,000 | aadA1 |

| 0008-301 | 08/15/00 | PSU | Bovine | 5 | Mifflin | AMP CHL TET STR SUL SPT GEN KAN CEF XNL | 140; 7.5 | 5 | 1,000 | aadA1 |

| 0008-302 | 08/15/00 | PSU | Bovine | 6 | Mifflin | AMP CHL TET STR SUL SPT GEN KAN CEF XNL | 140; 7.5 | 5 | 1,000 | aadA1 |

| 0008-303 | 08/15/00 | PSU | Bovine | 6 | Mifflin | AMP CHL TET STR SUL SPT GEN KAN CEF XNL | 140; 7.5 | 1 | 1,000 | aadA1 |

| 0008-322 | 08/08/00 | PSU | Bovine | 7 | Somerset | AMP CHL TET STR SUL CEF XNL | 140 | 5 | None detected | |

| 0009-156 | 09/15/00 | NBC | Equine | 8 | Mercer, N.J. | AMP CHL TET STR SUL CEF XNL | 140 | 1 | None detected | |

| 0009-273 | 09/21/00 | NBC | Equine | 9 | Chester | AMP CHL TET STR SUL CEF XNL | 140 | 1 | None detected | |

| 0010-119 | 10/03/00 | NBC | Equine | 10 | Chester | AMP CHL TET STR SUL CEF XNL | 140 | 1 | None detected | |

| 0010-396 | 10/17/00 | NBC | Equine | 11 | Westchester, N.Y. | AMP CHL TET STR SUL CEF XNL | 140 | 1 | None detected | |

| 0010-473 | 10/05/00 | PSU | Bovine | 12 | Somerset | AMP CHL TET STR SUL GEN KAN CEF XNL | 140 | 1 | None detected | |

| 0012-46 | 10/20/00 | PSU | Bovine | 13 | Lancaster | AMP CHL TET STR SUL CEF XNL | 140 | 1 | None detected | |

| 0012-47 | 11/02/00 | PSU | Bovine | 14 | Somerset | AMP CHL TET STR SUL KAN CEF XNL | 140 | 1 | None detected | |

| 0012-118 | 11/27/01 | NBC | Bovine | 15 | Lancaster | AMP CHL TET STR SUL CEF XNL | 140 | 1 | None detected | |

| 0101-400 | 11/28/00 | PSU | Bovine | 16 | Lancaster | AMP CHL TET STR SUL CEF XNL | 140 | 1 | None detected | |

| 0101-401 | 12/06/00 | PSU | Bovine | 17 | Washington | AMP CHL TET STR SUL SPT GEN KAN CEF XNL | 140; 7.5 | 5 | 1,000 | aadA1 |

| 0101-406 | 01/11/01 | PSU | Bovine | 18 | Somerset | AMP CHL TET STR SUL KAN CEF XNL | 140; 12; 10 | 1 | None detected | |

| 0101-408 | 01/13/01 | PSU | Bovine | 18 | Somerset | AMP CHL TET STR SUL KAN CEF XNL | 140; 20; 8.5 | 1 | None detected | |

| 0101-410 | 01/15/01 | PSU | Bovine | 19 | Lancaster | AMP CHL TET STR SUL CEF XNL | 140 | 1 | None detected | |

| 0102-1 | 02/01/01 | NBC | Bovine | 20 | Franklin | AMP CHL TET STR SUL SPT GEN KAN CEF XNL | 150; 20; 8 | 5 | 1,000 | aadA1 |

| 0102-2 | 02/01/01 | NBC | Equine | 21 | Chester | AMP CHL TET STR SUL SPT GEN KAN CEF XNL | 150; 20; 8 | 5 | 1,000 | aadA1 |

| 0102-163 | 02/01/01 | MDAg | Bovine | 2 | Kent | AMP CHL TET STR SUL CEF XNL | 140 | 12 | None detected | |

| 0103-47 | 03/01/01 | NBC | Bovine | 22 | Tioga | AMP CHL TET STR SUL KAN CEF XNL CRO | 140; 10 | 1 | None detected | |

| 0103-54 | 03/01/01 | PSU | Canine | 23 | Westmoreland | AMP CHL TET STR SUL CEF XNL | 140 | 1 | None detected | |

| 0103-55 | 12/06/00 | PSU | Bovine | 17 | Washington | AMP CHL TET STR SUL SPT GEN KAN CEF XNL | 150; 8 | 5 | 1,000 | aadA1 |

| 0103-57 | 02/08/01 | PSU | Bovine | 18 | Somerset | AMP CHL TET STR SUL KAN CEF XNL | 140 | 1 | None detected | |

| 0103-384 | 03/19/01 | PADLS-H | Pigeon | 24 | Northampton | AMP CHL TET STR SUL SPT GEN KAN CEF XNL | 150; 100; 8 | 5 | 1,000 | aadA1 |

| 0103-385 | 03/19/01 | PADLS-H | Bovine | 25 | Lancaster | AMP CHL TET STR SUL SPT GEN KAN CEF XNL | 140 | 5 | 1,000 | aadA1 |

| 0103-386 | 03/19/01 | PADLS-H | Bovine | 26 | Lancaster | AMP CHL TET STR SUL SPT GEN KAN CEF XNL | 140 | 5 | 1,000 | aadA1 |

| 0103-387 | 03/19/01 | PADLS-H | Bovine | 27 | Lebanon | AMP CHL TET STR SUL SPT GEN KAN CEF XNL | 140 | 5 | 1,000 | aadA1 |

| 0106-136 | 03/27/01 | PSU | Bovine | 28 | Montour | AMP CHL TET STR SUL SPT KAN CEF XNL | 140 | 1 | 1,000 | aadA1 |

| 0106-443 | 06/01/01 | PSU | Bovine | 29 | Mifflin | AMP CHL TET STR SUL CEF XNL | 140 | 1 | None detected | |

| 0107-158 | 06/01/01 | PADLS-H | Bovine | 30 | Perry | AMP CHL TET STR SUL SPT GEN KAN CEF XNL | 140 | 5 | 1,000 | aadA1 |

| 0107-378 | 06/19/01 | PSU | Bovine | 31 | Somerset | AMP CHL TET STR SUL KAN CEF XNL | 140 | 1 | None detected | |

| 0107-379 | 06/21/01 | PSU | Bovine | 32 | Mifflin | AMP CHL TET STR SUL CEF XNL | 140; 40 | 1 | None detected | |

| 0107-380 | 07/03/01 | PSU | Bovine | 33 | Mercer | AMP CHL TET STR SUL CEF XNL | 140 | 1 | None detected | |

| 0107-386 | 07/05/01 | PSU | Bovine | 34 | Somerset | AMP CHL TET STR SUL KAN CEF XNL | 140 | 1 | None detected | |

| 0108-190 | 08/01/01 | NBC | Bovine | 35 | York | AMP CHL TET STR SUL KAN CEF XNL | 140 | 5 | None detected |

For all isolates listed, blaCMY gene, 631.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

All isolates were shown by routine testing to have an MDR phenotype. All 42 MDR isolates expressed resistance to CEF and XNL; one isolate also showed resistance to CRO. MICs were not determined, but all CEF- and XNL-resistant isolates showed intermediate susceptibility to CRO (zone diameter range, 14 to 20 mm).

In all, seven different MDR patterns were observed. There appeared to be a common core of AMP, CHL, TET, STR, SUL, CEF, and XNL resistance, but additional resistance to SPT, KAN, and GEN was frequently observed. No nalidixic acid or ciprofloxacin resistance was observed.

Plasmid analysis.

The results of plasmid profile analysis are shown in Table 1. Twenty-seven isolates harbored a single plasmid of approximately 140 kb. A further 11 isolates harbored a plasmid of approximately 140 kb in combination with one or more additional plasmids. The plasmid profiles 158; 100; 8 and 150; 8 (respectively containing three plasmids of 150, 100, and 8 kb and two plasmids of 150 and 8 kb) were represented by single strains, and two isolates had the profile 150; 20; 8 kb. REFP analysis with four different restriction enzymes (PstI, SmaI, HindIII, and EcoRV) indicated that although the majority of isolates harbored a single plasmid of 140 kb, this plasmid was not identical in all strains (results not shown). Although heterogeneity was observed in the fingerprints generated with each enzyme, it was clear that the 140-kb plasmids belonged to a highly related family. In those isolates with more than one plasmid, it followed that isolates with identical plasmid profiles had identical REFPs. The only exception to this was isolate 0101-401, whose REFP differed from that observed in isolates from sources 5 and 6, which also showed the plasmid profile 140; 7.5.

PFGE.

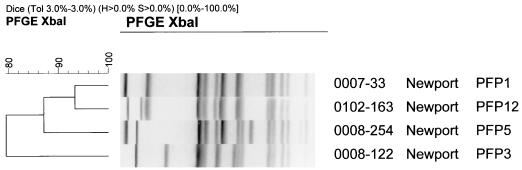

Four PFGE profiles (PFPs) were observed from the 42 isolates in the study when total genomic DNA was digested with XbaI. PFP 1 was seen in 26 of 42 isolates (62%), and PFP 5 was represented by 14 of 42 isolates (33%). Two other PFPs (PFP 3 and 12) were represented by a single strain. PFP 1, 3, 5, and 12 are illustrated in Fig. 1. A dendrogram generated from Dice coefficients of similarity indicated that all four PFPs were highly related, with Dice values greater than 75%. PFPs 1 and 5 showed almost 84% similarity.

FIG. 1.

PFGE profiles of S. enterica serotype Newport isolates 0007-33, 0008-122, 0008-254, and 0102-163, representing PFPs 1, 3, 5, and 12, respectively. Isolates were digested overnight with the restriction enzyme XbaI and run on a 1% agarose gel at 14°C for 20 h at 6 V cm−1 with pulse times from 5 to 50 s. A dendrogram was generated with BioNumerics software and shows that all isolates are highly related, with similarity coefficients greater than 75%.

The predominant PFPs (1 and 5) were observed in isolates from both bovine and equine sources. The large number of equine isolates in this study reflects the fact that the NBC is primarily an equine hospital. Each of the five horses was admitted to the NBC independently of the others. Three horses were from Pennsylvania, one horse was from New Jersey, and one was from New York. The bovine cases were well distributed, and preliminary Geographic Information System mapping indicates that clusters were observed. For example, there were six cases in Lancaster County; four of these showed PFP 1 and were isolated in October (1) and November 2000 (2) and January 2001 (1). In March 2001, two additional cases were observed in Lancaster County, both of which showed PFP 5. Similar clusters were observed in Mifflin and Somerset Counties. No epidemiological information was available for the porcine, canine, or pigeon isolates.

PCR detection of integrons and gene cassettes.

Integrons were detected in 16 of the 42 isolates, and all of these strains expressed additional resistance to spectinomycin. A fragment of approximately 1,000 bp was amplified with the intI-F and aadAI-R primers, confirming the presence of the aadAI gene cassette within an integron in these 16 isolates.

PCR detection of the blaCMY gene.

All isolates in this study showed the presence of a fragment of approximately 631 bp, as predicted, with the blaCMY gene primers.

DISCUSSION

Resistance to β-lactam antibiotics is widespread among strains of Salmonella. The presence of extended-spectrum β-lactamases has been reported, and more recently, resistance to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins has emerged. The presence of a plasmid-mediated CMY-2 β-lactamase gene was first reported in Salmonella in an isolate of Salmonella serotype Senftenberg from an Algerian child in 1997 (12). Recently, plasmid-mediated CMY-2 AmpC β-lactamases have been identified in Salmonella in the United States (5, 6, 31). The blaCMY-2 gene has been shown to be present in Salmonella serotype Newport (31), and there is mounting evidence that this MDR serotype is becoming increasingly prevalent in the United States (5, 31).

In the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System for enteric bacteria (NARMS-EB) Veterinary Isolates Final Report of 1998, 3,318 Salmonella strains were tested for resistance to 17 antimicrobial agents, and 93 of 3,225 isolates (2.8%) were resistant to XNL (17). In addition, 158 of 3,078 isolates (4.8%) were resistant to CEF, and 41 of 3,242 isolates (1.2%) were CRO-resistant. Resistance to XNL was observed in a variety of serotypes, including Typhimurium, Heidelberg, Hadar, Agona, Infantis, Senftenberg, and Bredeney. The NARMS 1999 annual report showed that the figures from human isolates were 2, 4, and 0.4% for XNL, CEF, and CRO resistance, respectively (18). When compared with the corresponding 1998 figures from NARMS of 1, 2.3, and 0.7%, it would appear that resistance to the cephalosporin antibiotics is increasing in Salmonella in the United States.

Our present findings suggest that cephalosporin-resistant Salmonella serotype Newport strains show some genotypic heterogeneity. Four different PFPs, namely, PFPs 1, 3, 5, and 12, were identified in resistant strains. PFPs 1 and 5 predominated and were observed in 62 and 33% of isolates, respectively. A Dice (4) coefficient of similarity derived from a comparison of PFP 1 and PFP 5 indicated that the strains were approximately 84% similar and that there were only five band differences between the two profiles (Fig. 1). GIS mapping incorporating PFPs and antimicrobial resistance patterns has been performed on all bovine cases submitted to the SRC from July 2000 to April 2002, and the results from this analysis are being submitted for publication elsewhere.

In the majority of isolates in this study (29 of 42), we observed a plasmid of approximately 140 kb. Plasmid transfer by conjugation was unsuccessful (results not shown), and we made no attempt to mobilize or transform these plasmids, but work is currently under way to confirm the presence of the blaCMY gene on plasmid DNA. The blaCMY-2 gene described in Salmonella by Winokur and colleagues (31) was found to be located on nonconjugative plasmids of approximately 75 kb. In contrast, Fey and colleagues showed that a CMY-2 β-lactamase in serotype Typhimurium isolates from Nebraska was located on a conjugative plasmid of approximately 160 kb (6). In both instances, the cephalosporin resistance cotransferred with additional resistance markers observed in these strains. The above evidence suggests that, rather than witnessing the expansion of a single MDR clone, there is the possibility of dissemination of an MDR replicon that may be capable of transfer among a broad range of enterobacterial hosts, thus ensuring efficient maintenance in the animal reservoir in the presence of adequate selection pressure. This hypothesis is strengthened by the results obtained by Winokur and colleagues (32), who showed evidence of transfer of CMY-2 AmpC β-lactamase plasmids between E. coli and Salmonella from food animals and humans.

Integrons were observed in 16 of 42 isolates (38%) in this study. Integrons are potentially independently mobile DNA elements (27) that encode a recA-independent, site-specific integration system responsible for the acquisition of multiple small mobile elements called gene cassettes that, in turn, encode antibiotic resistance genes (9). Integrons have been shown to be integrated within the chromosome in Salmonella serotype Typhimurium phage type 104 (DT104) and have also been described on plasmid DNA in Salmonella serovar Enteritidis (23, 25). The location of the integrons in serotype Newport isolates from this study remains to be determined, and work is currently under way to confirm the location of the integron and the aadAI gene cassette.

Our results highlight the benefits obtained by performing multiple analyses on all isolates. When the results from PFGE were analyzed discretely, 26 isolates showed PFP 1. However, the addition of plasmid profile analysis data allowed this homogeneous group to be further divided into seven distinct subgroups. Similarly, PFP 5 comprised five different plasmid profile subgroups. The plasmid profile subgroups could be further differentiated by plasmid REFP analysis, but even without this additional level of discrimination, the data show that at a local level (temporally and/or geographically related), plasmid analyses may provide additional information during epidemiological investigations

When infection with MDR serotype Newport was first identified on a dairy farm, the results of infection were inevitably catastrophic and animal mortality was high. Not surprisingly, perhaps, morbidity and mortality in dairy herds are highest in periparturient cows and neonatal calves, but clinical disease can occur in animals at any stage. It has been shown that once Salmonella serotype Typhimurium enters a dairy herd, it can persist for as long as 3.5 years (8). It is also possible that serotypes other than Typhimurium may persist in this and similar environments at low levels for long periods of time. For example, one report showed that serotype Newport can persist for up to 14 months (3), and we observed one source in our study (source 2) in which infection was apparent for more than 10 months. Resolution of the acute disease to an active carrier state may have resulted in persistent shedding of the organisms over this long period.

XNL is an expanded-spectrum, injectable cephalosporin developed solely for veterinary therapeutic use. First approved by the Food and Drug Administration's Center for Veterinary Medicine for treatment of bovine respiratory disease in 1988, it has since been registered worldwide for treatment of gram-positive and gram-negative bacterial infections in cattle, swine, sheep, horses, dogs, day-old chicks, and turkey poults. XNL has been shown to be readily inactivated and degraded in bacterial ecosystems, including manures, that are associated with animals; it is also inactivated and mineralized in soils and is subject to photolytic and hydrolytic mechanisms of inactivation. Thus, it has been hypothesized that the potential for bacteria associated with treated animals to be exposed to XNL is low (S. F. Kotarski, R. E. Hornish, W. J. Smolenski, S. A. Salmon, J. F. Caputo, F. M. Kausche, S. A. Brown, E. J. Robb, E. S. Portis, J. L. Watts, K. K. Thum, J. L. Napier, and J. W. Halberg, abstr. from the FDA/CVM 2001 Natl. Antimicrob. Resistance Monitoring System Sci. Meet. on 15 and 16 March 2001). However, it will be speculated (and, indeed, it has been speculated) that the therapeutic use of XNL in veterinary medicine may be associated with the acquisition of cephalosporin resistance by bacteria (31).

It should be noted, however, that in both the original Klebsiella strain from which the blaCMY-2 gene was isolated and characterized and in all reported cases of this gene in Salmonella serotypes, the cephalosporin resistance cotransferred with additional resistance markers. Thus, the potential for coselection of this gene, if located on an MDR replicon, may not be dependent on any particular antibiotic but rather may be a result of more general antimicrobial use.

There is a critical need to develop methods to control the spread of Salmonella infection on dairy farms by instituting biosecurity and containment practices in addition to enhanced farm management. In this way, the need for extensive antimicrobial treatment of individual animals or herds can be minimized. Veterinarians should be encouraged to develop suitable nonantibiotic treatment and management strategies that can be applied when salmonellosis is identified or suspected in food-producing animals. It is reasonable to hypothesize that in the presence of any suitable antibiotic selection pressure, the genes or replicons responsible for MDR in Salmonella serotype Newport may be transferred not only to other pathogenic serotypes of Salmonella but also to other susceptible organisms in the same environment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by funding from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture.

We thank William Higgens (Maryland Department of Agriculture) for providing strains. We also thank David Platt for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anand, C. M., M. C. Finlayson, J. Z. Garson, and M. L. Larson. 1980. An institutional outbreak of salmonellosis due to lactose-fermenting Salmonella Newport. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 74:657-660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauernfeind, A., I. Stemplinger, R. Jungwirth, and H. Giamarellou. 1996. Characterization of the plasmidic β-lactamase CMY-2, which is responsible for cephamycin resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:221-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clegg, F. G., S. N. Chiejina, A. L. Duncan, R. N. Kay, and C. Wray. 1983. Outbreaks of Salmonella newport infection in dairy herds and their relationship to management and contamination of the environment. Vet. Rec. 112:580-584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dice, L. R. 1945. Measures of the amount of ecological association between species. Ecology 26:297-302. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunne, E. F., P. D. Fey, P. Kludt, et al. 2000. Emergence of domestically acquired ceftriaxone-resistant Salmonella infections associated with AmpC β-lactamase. JAMA 284:3151-3156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fey, P. D., T. J. Safranek, M. E. Rupp, E. F. Dunne, E. Ribot, P. C. Iwen, P. A. Bradford, F. J. Angelo, and S. H. Hinrichs. 2000. Ceftriaxone-resistant Salmonella infection acquired by a child from cattle. N. Engl. J. Med. 342:1242-1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fontaine, R. E., S. Arnon, W. T. Martin, T. M. Vernon, Jr., E. J. Gangarosa, J. J. Farmer III, A. B. Moran, J. H. Silliker, and D. L. Decker. 1978. Raw hamburger: an interstate common source of human salmonellosis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 107:36-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giles, N., S. N. Hopper, and C. Wray. 1989. Persistence of S. typhimurium in a large dairy herd. Epidemiol. Infect. 103:235-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall, R. M., and C. M. Collis. 1995. Mobile gene cassettes and integrons: capture and spread of genes by site-specific recombination. Mol. Microbiol. 15:593-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heinitz, M. L., R. D. Ruble, D. E. Wagner, and S. R. Tatini. 2000. Incidence of Salmonella in fish and seafood. J. Food. Prot. 63:579-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horwitz, M. A., R. A. Pollard, M. H. Merson, and S. M. Martin. 1977. A large outbreak of foodborne salmonellosis on the Navajo National Indian Reservation, epidemiology and secondary transmission. Am. J. Public Health 67:1071-1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koeck, J. L., G. Arlet, A. Phillippon, S. Basmaciogullari, H. V. Thien, Y. Buisson, and J. D. Cavallo. 1997. A plasmid-mediated CMY-2 AmpC β-lactamase from an Algerian clinical isolate of Salmonella senftenberg. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 152:255-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lyytikainen, O., J. Koort, L. Ward, R. Schildt, P. Ruutu, E. Japisson, M. Tomonen, and A. Siitonen. 2000. Molecular epidemiology of an outbreak of Salmonella enterica serotype Newport in Finland and the United Kingdom. Epidemiol. Infect. 124:185-192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morse, E. V., M. A. Duncan, E. A. Page, and J. F. Fessler. 1976. Salmonellosis in equidae: a study of 23 cases. Cornell Vet. 66:198-213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.M'Zali, F. H., J. Heritage, D. M. Gascoyne-Binzi, M. Denton, N. J. Todd, and P. M. Hawkey. 1997. Transcontinental importation into the UK of Escherichia coli expressing a plasmid-mediated AmpC-type β-lactamase exposed during an outbreak of SHV-5 extended-spectrum β-lactamase in a Leeds hospital. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 40:823-831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Narain, J. P., and J. P. Lofgren. 1989. Epidemic of restaurant-associated illness due to Salmonella newport. South. Med. J. 82:837-840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System. 1998. National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System: enteric bacteria, 1998 annual report.

- 18.National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System. 1999. National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System: 1999 annual report.

- 19.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1997. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests, 6th ed. Approved standard. NCCLS document M2-A6. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Villanova, Pa.

- 20.Old, D. C., S. C. Rankin, and P. B. Crichton. 1999. Assessment of strain relatedness among Salmonella serotypes Salinatis, Duisburg, and Sandiego by biotyping, ribotyping, IS200 fingerprinting, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1687-1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pacer, R. E., J. S. Spika, M. C. Thurmond, N. Hargrett-Bean, and M. E. Potter. 1989. Prevalence of Salmonella and multiple antimicrobial-resistant Salmonella in California dairies. JAMA 195:59-63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rankin, S. C., C. E. Benson, and D. J. Platt. 1995. The distribution of serotype-specific plasmids among different subgroups of Salmonella enterica serotype Enteritidis: characterization of molecular variants by restriction enzyme fragmentation patterns. Epidemiol. Infect. 114:25-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rankin, S., and M. J. Coyne. 1998. Multiple antibiotic resistance in Salmonella enterica serotype Enteritidis. Lancet 351:1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riley, L. W., G. T. DiFerdinando, Jr., T. M. DeMelfi, and M. L. Cohen. 1983. Evaluation of isolated cases of salmonellosis by plasmid profile analysis: introduction and transmission of a bacterial clone by pre-cooked roast beef. J. Infect. Dis. 148:12-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sandvang, D., F. M. Aarestrup, and L. B. Jensen. 1997. Characterization of integrons and antibiotic resistance genes in Danish multiresistant Salmonella enterica Typhimurium DT104. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 160:37-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spika, J. S., S. H. Waterman, G. W. Hoo, M. E. St. Louis, R. E. Pacer, S. M. James, M. L. Bissett, L. W. Mayer, J. Y. Chiu, B. Hall, et al. 1987. Chloramphenicol-resistant Salmonella newport traced through hamburger to dairy farms: a major persisting source of human salmonellosis in California. N. Engl. J. Med. 316:565-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stokes, H. W., and R. M. Hall. 1989. A novel family of potentially mobile DNA elements encoding site-specific gene integration functions: integrons. Mol. Microbiol. 3:1669-1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Traub-Dargatz, J. L., M. D. Salman, and R. L. Jones. 1990. Epidemiological study of salmonellae shedding in the feces of horses and potential risk factors for development of the infection in hospitalized horses. JAMA 196:1617-1622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Beneden, C. A., W. E. Keene, R. A. Strang, D. H. Werker, A. S. King, B. Mahon, K. Hedberg, A. Bell, M. T. Kelly, V. K. Balan, W. R. MacKenzie, and D. Fleming. 1999. Multinational outbreak of Salmonella enterica serotype Newport infections due to contaminated alfalfa sprouts. JAMA 281:158-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wegener, H. C., L. Baggesen, J. Neimann, and S. V. Nielsen. 1997. An outbreak of human salmonellosis in Denmark caused by alfalfa sprouts, p. 587-589. In Proceedings and abstracts of the International Symposium on Salmonella and Salmonellosis, Ploufragan, France.

- 31.Winokur, P. L., A. Bruggemann, D. L. DeSalvo, L. Hoffman, M. D. Apley, E. K. Uhlenhopp, M. A. Pfaller, and G. V. Doern. 2000. Animal and human multidrug-resistant, cephalosporin-resistant Salmonella isolates expressing a plasmid-mediated CMY-2 AmpC β-lactamase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2777-2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Winokur, P. L., D. L. Vonstein, L. Hoffman, E. K. Uhlenhopp, and G. V. Doern. 2001. Evidence for transfer of CMY-2 AmpC β-lactamase plasmids between Escherichia coli and Salmonella isolates from food animals and humans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2716-2722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]