Abstract

Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans is a major pathogen in periodontitis. Data on the clinical relevance of serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody levels against this species are controversial. The aim of the present study was to elucidate how different strains used as antigens in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) influence the detection of individuals with elevated serum IgG levels against A. actinomycetemcomitans. We hypothesized that the highest antibody levels are targeted to the autologous strains. A total of 19 strains—six antigenically diverse reference strains (serotypes a through e and a nonserotypeable strain) and 13 serotyped autologous strains—were used as whole-cell antigens in ELISA. Serum samples were from 26 untreated adult patients with periodontitis, whose subgingival bacterial samples were either culture positive (n = 13) or culture negative (n = 13) for A. actinomycetemcomitans, and from 10 culture-negative nonperiodontitis subjects. The highest individual (P < 0.05) IgG levels against the reference strains were most commonly against serotypes a and b in patients and against serotype c in nonperiodontitis subjects. The culture-positive patients had the highest (P < 0.05) IgG antibody levels against their autologous strains and against the reference strains of the same serotype. On the contrary, for these patients the levels of antibody against the reference strains of other serotypes were comparable to those of the nonperiodontitis subjects. The results indicated that the serum IgG antibody levels against A. actinomycetemcomitans strongly depend on the strains used as antigens in the ELISA. Elevated serum IgG levels against A. actinomycetemcomitans can be detected equally well using either the autologous strains or a variety of antigenically diverse reference strains as antigens.

Periodontitis is a persistent bacterial infection in tooth-supporting tissues and may eventually lead to loss of teeth. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, a small, nonmotile, facultatively anaerobic coccobacillus, is a major pathogen in periodontitis (1). The species is divided into five genetically diverse (3, 27) serotypes (29, 23). However, up to every 10th bacterium-positive individual carries a nonserotypeable strain (20). Recently, further antigenic heterogeneity has been detected within serotype b strains (14).

In industrialized countries, oral colonization by A. actinomycetemcomitans is most commonly monoclonal (4). Additionally, spontaneous or treatment-induced changes in an A. actinomycetemcomitans clone(s) are rare in individuals persistently culture positive for the species (24; W. Z. Chen, S. Rich, and C. Chen. Abstr. Int. Assoc. Dent. Res. 80th Gen. Sess., p. 1450, 2002). There probably are differences in the A. actinomycetemcomitans serotype distribution with respect to periodontal conditions. For example, serotype b is the most frequent serotype in North American patients with periodontitis (29), and serotype c is the most frequent in periodontally healthy Finnish subjects (6).

Data on the clinical significance of serum antibody levels against A. actinomycetemcomitans are discrepant (9, 15). Methodological factors may at least partly explain the inconsistent findings. For instance, determination of antibody levels commonly relies on using a single reference strain (usually of serotype b) as the antigen in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (10, 16, 25), although the use of a single strain may lead to underestimation of the number of seropositive individuals (19). However, choice of multiple A. actinomycetemcomitans strains as antigens in ELISA has caught little attention. Similarly, limited knowledge is available about the levels of antibody against the autologous A. actinomycetemcomitans strains versus those against its reference strains in the same culture-positive individuals. As can be anticipated, patients with periodontitis mainly display high serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels against their autologous strains (11) but may, instead, present low levels of IgG against reference strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans (28). Regarding knowledge on other oral species, it seems clear that some high responders were only detected when the autologous strains of Eikenella corrodens were used as antigens in the ELISA (5).

Our previous studies indicate that up to 20% of A. actinomycetemcomitans strains of unrelated subjects represent serotypes other than the three most common serotypes, a, b, and c (6). To our knowledge, no studies have individually compared the results of the serum IgG antibody levels against serotyped, autologous strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans in addition to an extensive variety of serotypeable and nonserotypeable strains. In order to serologically identify patients infected by A. actinomycetemcomitans, the aim of our study was to determine whether reference strains with various antigenic properties could be used in ELISAs instead of the autologous strains. The present study population comprised patients with periodontitis, who were either culture positive or culture negative for A. actinomycetemcomitans, and persons without periodontitis. The study design allowed comparisons of the serum IgG levels against the A. actinomycetemcomitans reference strains between the study groups but also allowed comparisons of the IgG antibody levels against the autologous strains and the reference strains in each culture-positive patient.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study subjects and samples.

The study included serum samples from 26 untreated adult patients with periodontitis (age [mean ± standard deviations {SD}], 50.3 ± 7.3 years; range, 32 to 69 years; males, n = 20; females, n = 6), whose subgingival samples were either culture positive (n = 13) or culture negative (n = 13) for A. actinomycetemcomitans. Each patient had clinical and/or radiographic periodontal attachment loss at more than six teeth. Ten nonperiodontitis subjects (age [mean ± SD], 40.6 ± 12.8 years; range, 23 to 62 years; males, n = 2; females, n = 8) served as controls. These subjects had occasional gingival bleeding on probing but no clinical periodontal attachment loss, and the distance from the cementoenamel junction to the alveolar bone margin did not exceed 3 mm in panorama radiographs. Blood samples were drawn by venipuncture, and after centrifugation (1,000 × g for 10 min), the sera were stored at −70°C in 100-μl aliquots until use. The study plan was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Institute of Dentistry, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, and the patients signed written informed consents.

Subgingival bacterial samples were obtained with sterile curettes from four to six of the deepest and most-inflamed periodontal pockets of the patients and from the approximal sites of all teeth of the nonperiodontitis subjects. The samples from each subject were pooled in a single vial containing VMGA III transport medium (17) and cultured within 24 h for A. actinomycetemcomitans, as described previously (23). One random strain of A. actinomycetemcomitans per each culture-positive patient was selected to represent the autologous strain. This strain was used as the antigen in the ELISA in order to determine the serum antibody level against the autologous strain of that patient.

Serotyping.

The A. actinomycetemcomitans strains from the patients used as antigens in the ELISA were serotyped by an immunodiffusion assay. On the plates, serotype-specific rabbit antisera raised against five serotypes (a, ATCC 29523; b, ATCC 43718; c, ATCC 33384; d, IDH 781; e, IDH 1705) were used as antibodies, and autoclaved A. actinomycetemcomitans cell extracts were used as antigens (23).

ELISA.

A modification of the ELISA (7) was used to determine the serum IgG antibody levels against A. actinomycetemcomitans. Briefly, formalin-fixed whole bacterial cells were suspended in antigen buffer (0.1 M sodium carbonate, pH 9.6), adjusted to give an optical density at 580 nm of 0.15 and used to coat 96-well microtiter plates (Cliniplate UNI; Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland). The plates were sealed, incubated at room temperature (RT) for 4 h, and stored at 4°C until used within 24 h.

The microtiter plates were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (10 mM phosphate, pH 7.4, containing 150 mM NaCl) containing 0.05% Tween 20. The wells were blocked with postcoating buffer (PBS containing 5% bovine serum albumin) for 30 min on a rotating plate. Serum diluted in antibody buffer (PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 and 0.5% bovine serum albumin) was added to each well and incubated at RT for 2 h. For the determinations, four dilutions (1:1,500, 1:4,500, 1:13,500, and 1:40,500) of each sample were used in duplicate. After washing the wells three times, 100 μl of peroxidase-conjugated anti-human IgG (Fc specific; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) diluted with antibody buffer (1:20,000) was used as a detection antibody, and the plates were incubated at RT for 1 h. After washing three times, 100 μl of substrate buffer (SIGMA FAST o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride tablet sets; Sigma) was added and the color was developed in the dark for 45 min. The enzymatic reaction was stopped by adding 50 μl of 3 N HCl, and the absorbances at 492 nm were measured by a microtiter plate reader (Multiscan RC; Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland).

Each serum sample included in the study was tested against each of the six reference strains. Serum samples of the A. actinomycetemcomitans culture-positive patients (n = 13) were additionally tested against their own autologous A. actinomycetemcomitans strains.

A control for nonspecific binding (no serum sample) and two controls to monitor interplate assay variations were applied on each plate. The “low control” consisted of pooled serum from cord blood, and the “high control” consisted of a high-responding serum.

As we used four dilutions of each sample, the net absorbances formed a dose-response curve. The IgG levels of all sera tested were expressed as ELISA units (EU), which were calculated as area (millimeters square) under the dose-response curve using the following formula: area = X · (n − 1) · [2(ΣAmd) +ΣAfd + ΣAld]/4r, where A is the net absorbance at different dilutions (md, middle dilutions; fd, first dilution; ld, last dilution), n − 1 is the number of intervals (n dilutions), X is the orbit ray interval used on the graph paper (here, 10 mm), and r is the number of replicates (26).

Statistical methods.

The Mann-Whitney U test was used to determine the significance of the differences in the mean EU between the three study groups and chi-square statistics in the frequency distributions of categorized variables between the study groups. A P of <0.05 was interpreted as statistically significant.

RESULTS

ELISA quality control.

In the ELISA, the interassay coefficient of variation was 4.1% as calculated from the high-control serum sample measured on each plate. The SD between the duplicate measurements describing the intra-assay reproducibility was 0.20 EU. A “zero level” ± SD for the serum determinations was 3.40 ± 0.11 EU, which was obtained by measuring the IgG value of the low control on each microtiter plate.

A. actinomycetemcomitans serotype distribution of the culture-positive subjects.

One autologous strain from each A. actinomycetemcomitans culture-positive patient (n = 13) was serotyped by immunodiffusion. The number of patients harboring strains of serotypes a, b, and c were 5 (38%), 6 (46%), and 1 (8%), respectively. One patient (8%) harbored a nonserotypeable strain, whereas none displayed strains representing serotypes d or e. All nonperiodontitis subjects were culture negative for A. actinomycetemcomitans.

ELISA results in the three study groups.

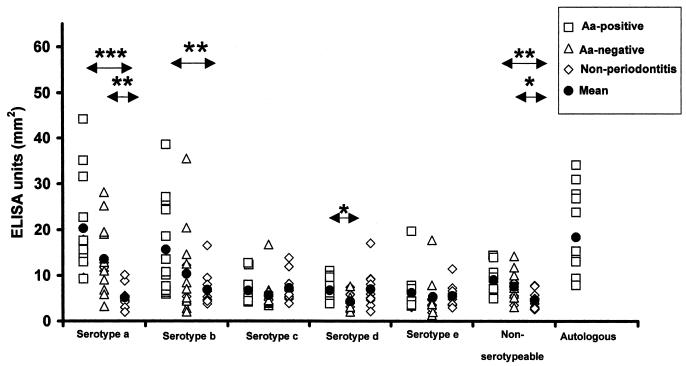

Fig. 1 shows the individual and mean serum IgG levels against all test strains in the three study groups. In culture-positive patients, the mean IgG level against their autologous strains was significantly (P < 0.01) higher than those against the reference strains of serotypes c, d, or e or the nonserotypeable strain. The IgG levels against serotype a (mean ± SD, 16.92 ± 9.53 EU versus 5.18 ± 2.56 EU), serotype b (13 ± 10.05 EU versus 6.88 ± 3.84 EU), and the nonserotypeable strain (8.34 ± 3.02 EU versus 4.64 ± 1.97 EU) were higher (P < 0.001, P = 0.052, and P < 0.01, respectively) in patients than in nonperiodontitis subjects, respectively. The difference in the levels of IgG against serotype d was the only statistically significant difference between A. actinomycetemcomitans culture-positive and culture-negative patients.

FIG. 1.

Individual and mean serum IgG levels against A. actinomycetemcomitans (Aa) in three groups of subjects: patients with periodontitis, culture positive (n = 13) (□) or negative (n = 13) (▵) for A. actinomycetemcomitans, and nonperiodontitis subjects (n = 10) (⋄). The serum IgG levels were determined against six reference strains separately. In addition, the serum IgG levels of the culture-positive patients were determined against their own autologous strain. The mean EU of each group is depicted by a black circle. The statistically significant differences between the groups are pointed out by stars (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

Since Fig. 1 demonstrated an individual variation in the IgG values, a further analysis was carried out to clarify against which test strains the individually highest values were targeted (Table 1). The highest values were most commonly against serotype b in culture-positive patients, serotype a in culture-negative patients, and serotype c in nonperiodontitis subjects. The difference in the frequency distribution of the individually highest IgG levels was statistically significant (P < 0.01) between the study groups.

TABLE 1.

Distribution of the individually highest serum IgG levels against the A. actinomycetemcomitans reference strains used as antigens in ELISAa

| Strain (serotype) | No. (%) of subjects with individually highest antibody levels |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Culture-positive patients | Culture-negative patients | Nonperiodontitis subjects | |

| ATCC 29523 (a) | 5 (38.5) | 8 (61.5) | |

| ATCC 43718 (b) | 6 (46.1) | 3 (23.1) | 3 (30) |

| ATCC 33384 (c) | 1 (7.7) | 5 (50) | |

| IDH 781 (d) | 2 (20) | ||

| IDH 1705 (e) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (7.7) | |

| C59A (nonsero- typeable) | 1 (7.7) | ||

| Total | 13 (100) | 13 (100) | 10 (100) |

Statistically significant (P = 0.007) difference in the frequency distributions of the individually highest IgG levels between the study groups.

ELISA results of the culture-positive patients.

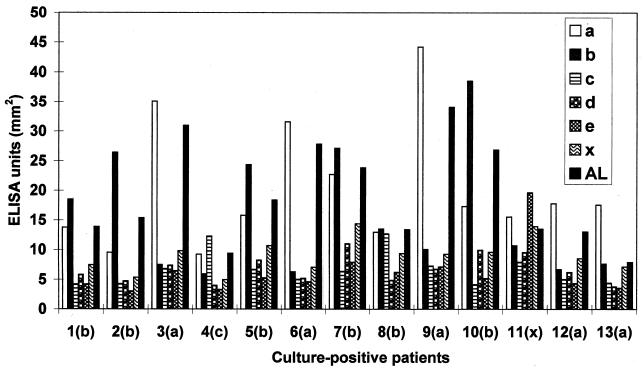

Figures 2 and 3 show the magnitude of the individual IgG levels against the autologous strains compared with those against the reference strains of the same or distinct serotype. Figure 2 shows that, except for one individual (subject 11), all culture-positive patients displayed their two highest IgG levels against their autologous strains and the reference strains of the same serotype. The patient whose autologous strain was nonserotypeable had the highest IgG level against serotype e (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Individual serum IgG levels against A. actinomycetemcomitans in culture-positive patients with periodontitis (n = 13). The patients are numbered from 1 to 13. The serotype of the autologous strain of each patient is shown in parentheses. The nonserotypeable strain is indicated (x).

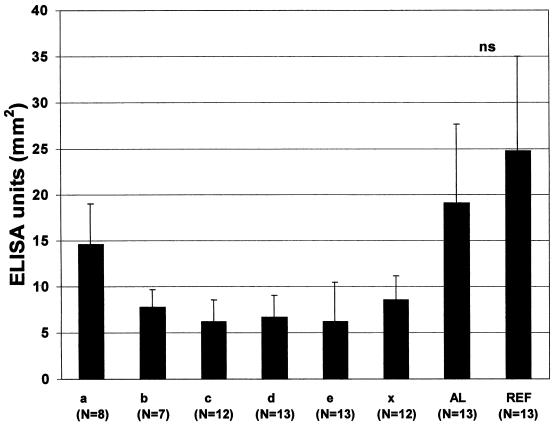

FIG. 3.

Comparison of the serum IgG levels against autologous strains and reference strains. Serum IgG levels of A. actinomycetemcomitans culture-positive patients (n = 13) were determined against autologous strains and reference strains a through x. The bars indicated by AL and REF represent the mean EU determined against autologous strains (AL) and the reference strains of the same serotype as the autologous strain (REF) of the patient. The bars a through x represent the mean serum IgG levels against other serotypes than AL and REF. The number of subjects is given in parentheses. The nonserotypeable strain is indicated (x). NS, not statistically significant. Error bars, SDs.

In the culture-positive patients, there was no significant difference (P = 0.139) between the serum IgG levels (mean ± SD) against the autologous strains (19.1 ± 8.6 mm2) and the reference strains of the corresponding serotypes (24.7 ± 10.3 mm2) (Fig. 3). In contrast serum IgG levels against the other reference strains were significantly (serotypes b, c, d, and e and the nonserotypeable strain, P < 0.001; serotype a, P < 0.05) lower than those against the autologous strain (except for serotype a) or the reference strain of the same serotype. The ELISA results (mean ± SD) for these other serotypes (a through e and the nonserotypeable strain) were 14.6 ± 4.4, 7.8 ± 1.9, 6.3 ± 2.4, 6.7 ± 2.3, 6.2 ± 4.3, and 8.7 ± 2.6 mm2, respectively. These mean values were calculated from the results for the patients whose autologous strain was not of the serotype in question. For example, bar a shows the mean EU against serotype a from eight patients whose autologous strain was not of serotype a (Fig. 3).

DISCUSSION

The results of the present study showed that the mean serum IgG antibody levels were significantly higher against the autologous strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans and the reference strain of the same serotype than against strains of any other serotype. The study hypothesis was that the individuals with cultivable subgingival A. actinomycetemcomitans would raise serum IgG antibodies predominantly against their autologous strains. The study design allowed comparisons of the IgG antibody results against a variety of antigenically diverse A. actinomycetemcomitans strains both within the individuals and between the study groups. Thus, in addition to testing the hypothesis, the study design also provided the possibility of searching for ELISA antigens that would be as efficient but not as laborious to use as autologous strains in large epidemiological studies.

To improve the reliability of the results without using an affinity-purified standard antibody, we used four dilutions of each sample in duplicates in the ELISA. We expressed the results as areas under the dilution curves (EU, in millimeters square) as described previously (22, 26). This enables the comparison of the serum IgG levels against different strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans without using a reference serum or an arbitrary definition of the EU. Since we used a total of 19 different strains as antigens in this study, the use of reference sera to calculate the results would have been difficult, and maybe even misleading. We would have had to use a different reference serum for each serotype to ensure that the reference serum had a relatively high IgG level against the strain to be used as antigen. This would have led to an arbitrary definition of the EU for several reference sera, creating problems in comparing the individual serum IgG levels against different serotypes. Furthermore, even if we had used a mixture of reference sera that each contained elevated IgG levels against one serotype, we would have had to use various arbitrary definitions of the EU for the serum mixture for all strains to be used as antigens in ELISA.

We used whole bacterial cells as antigens in ELISA to ensure detection of serum IgG antibodies against the A. actinomycetemcomitans species. Therefore, the effect of possible cross-reactions with closely related species was also tested. High- and low-responding sera were absorbed with intact cells of a Haemophilus aphrophilus strain (ATCC 19415), and the reactivities of the serum supernatants were measured against A. actinomycetemcomitans serotypes a through e and the nonserotypeable strain in ELISA. The difference in the IgG levels between the absorbed and the intact sera was in the range of interplate assay variations, suggesting that the majority of these antibodies were A. actinomycetemcomitans specific. This result is in accordance with a previous finding, where serum IgG levels measured against A. actinomycetemcomitans correlated poorly with those against H. aphrophilus, suggesting that the major humoral immune response was directed towards species-specific antigens rather than to cross-reacting antigens (11).

Although well-characterized, our study population was limited. A larger population would have increased the probability of including individuals harboring also the rare serotypes d and e, which would give a more complete covering of the serum IgG responses against the autologous and reference strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans. However, the importance of the careful choice of the antigen to be used in ELISA can clearly be seen in the results of the present study.

Using a single strain per patient as a representative of the colonizing A. actinomycetemcomitans population was considered sufficient in the present study, since most persistently A. actinomycetemcomitans-positive Finnish subjects have demonstrated a stable oral colonization by a single clonal type of the species (4, 24). Since a single A. actinomycetemcomitans strain per patient was serotyped, we cannot rule out the possibility that these patients' oral cavities could have been colonized with A. actinomycetemcomitans strains of multiple antigenically distinct clones. However, since previous results indicate that oral colonization by A. actinomycetemcomitans is generally monoclonal and pooling the bacterial samples obtained from multiple inflamed periodontal pockets of each individual likely results in isolating the dominant A. actinomycetemcomitans clone (23, 21, 8), we decided that serotyping a single strain per patient is sufficient for our purposes. Our findings support this decision, since the serum IgG levels of the A. actinomycetemcomitans culture-positive patients were individually clearly dominant against a single serotype. Elevated serum IgG levels against several serotypes of A. actinomycetemcomitans per individual have been reported by some other researchers (12, 28). Whether the discrepancy between their and our results was caused by differences in the study populations, simultaneous or sequential infections with strains of several A. actinomycetemcomitans serotypes could not be concluded from the results shown in those studies. Furthermore, Nakashima et al. (18) found two types of high-responding patients: the first group had high IgG antibodies only against A. actinomycetemcomitans serotype b, while the other group had high IgG antibodies against strains representing serotypes a, b, and c. Their study showed that the antibodies in the first group were mainly against serotype b-specific carbohydrate, while the antibodies of the other group were mainly reactive with lipopolysaccharides of all serotypes. Although these results are slightly different from ours, they also support the variation in serum IgG levels against different strains within individuals and emphasize the importance of using a sufficient variety of strains as antigens in ELISA in order to ensure the detection of seropositive individuals.

According to our results, the serum IgG level against the autologous strain was of the same magnitude as that against the reference strain of the same serotype. In other words, there was no statistically significant difference between the serum IgG levels against the autologous strains and the reference strains of the same serotype. In fact, the serum IgG levels against reference strains of the same serotype as the autologous strains were even higher than those against the autologous strains. This may be due to technical reasons. Smooth colony-type reference strains form homogeneous cell suspensions, whereas cells of the freshly isolated strains tend to aggregate. However, also a high antibody response could be detected against the fresh, clinical strains forming aggregates. Thus, the effect of cell aggregation on the ELISA results was interpreted as insignificant.

The most striking finding in our study was the major individual differences in serum IgG levels against different strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans. The dependence of serum IgG levels on the strain used as the antigen in the ELISA can clearly be seen in Fig. 2. The serum IgG levels of the culture-positive patients against the autologous A. actinomycetemcomitans strains and the reference strains of the same serotype were high, while their serum IgG levels against the other reference strains did not differ from the corresponding levels of the nonperiodontitis subjects. It has been observed previously that regardless of the A. actinomycetemcomitans serotype(s) by which the IgG response of a subject has been triggered, the most abundant antibodies recognize predominantly the serotype-specific epitopes (12). These findings support the significance of the serotype-specific antigens in eliciting the serum IgG response against A. actinomycetemcomitans. The findings also emphasize the importance of using several strains representing different serotypes as antigens in ELISA. On the basis of the large individual variation observed in the antibody levels against the reference strains, Tinoco et al. (28) suggested that autologous strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans should be used as antigens in ELISA. Our present results indicate that also the reference strains can be used, as long as a sufficiently large variety of serotypes is represented. This increases the feasibility of the antibody level measurements, since bacterial cultures for isolating autologous strains is not needed and the same battery of strains can be used as antigens for all study subjects.

Another interesting result in our study was that the distributions of the highest individual serum IgG levels against the five serotypes (a through e) and the nonserotypeable strain were different between patients and nonperiodontitis subjects. Although keeping in mind the limited size of the present study population, the fact that patients with periodontitis had the highest individual serum IgG levels most commonly against serotypes a and b and the healthy controls had the highest individual serum IgG levels against serotype c suggests that serotypes a and b are more related to the periodontal destruction than serotype c. This is in line with the previous studies, as it has been reported that serotype c is more common in periodontal health and serotypes a and b are more common in patients with periodontitis (2, 6, 13).

We conclude that, in order to ensure a high reliability of the ELISA results, it is crucial to use several serotypes as antigens in the A. actinomycetemcomitans ELISA. In our opinion elevated serum IgG levels against A. actinomycetemcomitans can be detected equally well using either the autologous strains or reference stains representing all serotypes of the species.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Academy of Finland (grants 45921, 44626, 48725, 77613, and 75953), by the Finnish Dental Association, and by the Finnish Dental Society Apollonia.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Academy of Periodontology. 1996. Periodontal diseases: pathogenesis and microbial factors. World Workshop in Periodontics. Consensus report. Ann. Periodontol. 1:926-932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asikainen, S., C. H. Lai, S. Alaluusua, and J. Slots. 1991. Distribution of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans serotypes in health and disease. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 6:115-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asikainen, S., C. Chen, and J. Slots. 1996. Likelihood of transmitting Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis in families with periodontitis. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 11:387-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asikainen, S., and C. Chen. 1999. Oral ecology and person-to-person transmission of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis. Periodontol. 2000: 20:65-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, C., and A. Ashimoto. 1998. Variable serum immunoglobulin G immune response to genetically distinct Eikenella corrodens strains coexisting in the human oral cavity. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 13:158-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dogan, B., M. H. Saarela, H. Jousimies-Somer, S. Alaluusua, and S. Asikainen. 1999. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans serotype e—biotypes, genetic diversity and distribution in relation to periodontal status. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 14:98-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ebersole, J. L., D. E. Frey, M. A. Taubman, and D. J. Smith. 1980. An ELISA for measuring serum antibodies to Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J. Periodontol. Res. 15:621-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ebersole, J. L., D. Cappelli, and M. N. Sandoval. 1994. Subgingival distribution of A. actinomycetemcomitans in periodontitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 21:65-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ebersole, J. L., D. Cappelli, and M. J. Steffen. 1995. Longitudinal dynamics of infection and serum antibody in A. actinomycetemcomitans periodontitis. Oral Dis. 1:129-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ebersole, J. L., M. J. Steffen, and D. Cappelli. 1999. Longitudinal human serum antibody responses to outer membrane antigens of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J. Clin. Periodontol. 26:732-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Genco, R. J., J. J. Zambon, and P. A. Murray. 1985. Serum and gingival fluid antibodies as adjuncts in the diagnosis of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans-associated periodontal disease. J. Periodontol. 56(Suppl. 11):41-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gmür, R., and P. C. Baehni. 1997. Serum immunoglobulin G responses to various Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans serotypes in a young ethnographically heterogeneous periodontitis patient group. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 12:1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haubek, D., K. Poulsen, S. Asikainen, and M. Kilian. 1995. Evidence for absence in northern Europe of especially virulent clonal types of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:395-401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan, J. B., M. B. Perry, L. L. MacLean, D. Furgang, M. E. Wilson, and D. H. Fine. 2001. Structural and genetic analyses of O polysaccharide from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans serotype f. Infect. Immun. 69:5375-5384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lamster, I. B., I. Kaluszhner-Shapira, M. Herrera-Abreu, R. Sinha, and J. T. Crbic. 1998. Serum antibody response to Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis: implications for periodontal diagnosis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 25:510-516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ling, T. Y., T. J. Sims, H. A. Chen, C. W. Whitney, B. J. Moncla, L. D. Engel, and R. C. Page. 1993. Titer and subclass distribution of serum IgG antibody reactive with Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in localized juvenile periodontitis. J. Clin. Immunol. 13:101-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Möller, Å. J. R. 1966. Examination of root canals and periapical tissues of human teeth. Odontol. Tidskr. 74:1-380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakashima, K., C. Usui, T. Koseki, T. Nishihara, and I. Ishikawa. 1998. Two different types of humoral immune response to Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in high-responder periodontitis patients. J. Med. Microbiol. 47:569-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nieminen, A. 1997. Clinical, microbiological, immunological and biochemical markers for treatment response. Ph.D. thesis. University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland.

- 20.Paju, S., M. Saarela, S. Alaluusua, P. Fives-Taylor, and S. Asikainen. 1998. Characterization of serologically nontypeable Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2019-2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Preus, H. R., J. J. Zambon, R. G. Dunford, and R. J. Genco. 1994. The distribution and transmission of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in families with established adult periodontitis. J. Periodontol. 65:2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pussinen, P. J., T. Vilkuna-Rautiainen, G. Alfthan, K. Mattila, and S. Asikainen. 2002. Multiserotype enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay as a diagnostic aid for periodontitis in large-scale studies. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:512-518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saarela, M., S. Asikainen, S. Alaluusua, L. Pyhälä, C. H. Lai, and H. Jousimies-Somer. 1992. Frequency and stability of mono- or poly-infection by Actinobacillus actinomycetencomitans serotypes a, b, c, d or e. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 7:277-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saarela, M., B. Dogan, S. Alaluusua, and S. Asikainen. 1999. Persistence of oral colonization by the same Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans strain(s). J. Periodontol. 70:504-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schenck, K., S. R. Porter, T. Tollefsen, J. R. Johansen, and C. Scully. 1989. Serum levels of antibodies against Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in various forms of human periodontitis. Acta Odontol. Scand. 47:271-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sedgwick, A. K., M. Ballow, K. Sparks, and R. C. Tilton. 1983. Rapid quantitative microenzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for tetanus antibodies. J. Clin. Microbiol. 18:104-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suzuki, N., Y. Nakano, Y. Yoshida, D. Ikeda, and T. Koga. 2001. Identification of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans serotypes by multiplex PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2002-2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tinoco, E. M. B., S. P. Lyngstadaas, H. R. Preus, and P. Gjermo. 1997. Attachment loss and serum antibody levels against autologous and reference strains of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in untreated localized juvenile periodontitis patients. J. Clin. Periodontol. 24:937-944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zambon, J. J., J. Slots, and R. J. Genco. 1983. Serology of oral Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and serotype distribution in human periodontal disease. Infect. Immun. 41:19-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]