Abstract

We have developed a rapid microarray-based assay for the reliable detection and discrimination of six species of the Listeria genus: L. monocytogenes, L. ivanovii, L. innocua, L. welshimeri, L. seeligeri, and L. grayi. The approach used in this study involves one-tube multiplex PCR amplification of six target bacterial virulence factor genes (iap, hly, inlB, plcA, plcB, and clpE), synthesis of fluorescently labeled single-stranded DNA, and hybridization to the multiple individual oligonucleotide probes specific for each Listeria species and immobilized on a glass surface. Results of the microarray analysis of 53 reference and clinical isolates of Listeria spp. demonstrated that this method allowed unambiguous identification of all six Listeria species based on sequence differences in the iap gene. Another virulence factor gene, hly, was used for detection and genotyping all L. monocytogenes, all L. ivanovii, and 8 of 11 L. seeligeri isolates. Other members of the genus Listeria and three L. seeligeri isolates did not contain the hly gene. There was complete agreement between the results of genotyping based on the hly and iap gene sequences. All L. monocytogenes isolates were found to be positive for the inlB, plcA, plcB, and clpE virulence genes specific only to this species. Our data on Listeria species analysis demonstrated that this microarray technique is a simple, rapid, and robust genotyping method that is also a potentially valuable tool for identification and characterization of bacterial pathogens in general.

The genus Listeria consists of six species: L. monocytogenes, L. ivanovii, L. innocua, L. welshimeri, L. seeligeri, and L. grayi. All Listeria species are ubiquitously distributed in nature and can often be found in soil, decaying plants, sewage, silage, dust, and water (3, 19). Two species, L. monocytogenes and L. ivanovii, are considered pathogenic for animals, with L. monocytogenes being predominantly associated with human illnesses such as meningitis, encephalitis, and sepsis (39, 40, 45). Among the risk groups (infants, pregnant women, elderly persons, and immunocompromised individuals), the worldwide case fatality rate for listeriosis is estimated to be as high as 36% (41). Infection of humans predominantly occurs as a result of occasional contamination of ready-to-eat and raw food products. Outbreaks and sporadic cases of listeriosis have been associated with contamination of different food items, including coleslaw, milk, pÂté, soft cheese, meat, and seafood products (14, 30, 40).

Conventional methods for detecting L. monocytogenes involve multiple selective enrichment steps followed by biochemical identification and serotyping (15, 27-29). These methods are time consuming, generally requiring at least 2 to 3 days (13, 16). A number of alternative biochemical, immunological, and molecular methods that shorten the time for Listeria sp. detection in food and environmental samples have been reported (1, 4). Molecular methods used for the genetic identification and characterization of Listeria isolates include PCR with primers specific for characteristic genes (6, 23, 31), restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis (42, 44), amplified fragment length polymorphism analysis (34), random amplification of polymorphic DNA (47), and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (25).

Several genetic markers, including 16S and 23S rRNA genes, 16 S-23S intergenic spacer regions, and certain virulence factor genes, have been reported to be useful targets for the PCR amplification and for differentiation among Listeria species (2, 6, 12, 21, 24, 31, 35, 48). Although PCR amplification followed by separation and characterization of DNA products by gel electrophoresis is a simple and sensitive method, this approach has a number of inherent shortcomings. Highly sensitive PCR amplification tends to generate more nonspecific DNA products, which complicate interpretation of results. Furthermore, in cases where multiplex PCR is used for the simultaneous detection of several genetic markers, these nonspecific products may be a significant problem (17). Therefore, there is a need for improved high-throughput methods for genotyping that are sensitive, highly discriminating, and robust.

A combination of PCR with DNA-DNA hybridization instead of gel electrophoresis significantly improves the specificity of target sequence detection in the presence of nonspecific PCR products (10). Microchip technology might provide an ideal solution to this problem. DNA and oligonucleotide microchips (microarrays) are widely used for genomic studies, including gene expression, genotyping, and single-nucleotide polymorphisms (22, 32, 33, 37, 38). Unlike other hybridization tools, such as microplates or dot blots for DNA-DNA hybridization with membrane-bound probes, miniature glass microchips are capable of containing DNA probes specific to thousands of individual target DNAs. Potentially, microarray technology allows the rapid determination of a complete genetic profile of a microorganism in one hybridization experiment. Thus, this approach may be a valuable tool for genetic screening and identification of microorganisms.

Previous studies employed oligonucleotide arrays for detection of genetic markers associated with bacterial and viral pathogenesis and drug resistance (9, 10). In the present study we used the combined PCR-microarray approach for reliable and accurate discrimination among six Listeria species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Table 1 lists the origins and descriptions of the Listeria strains used in this study. The strains were obtained from the Special Listeria Culture Collection, Institute of Hygiene and Microbiology, University of Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany, the American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga., and the collections of Anthony Hitchins and Farukh Khambaty of the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, Food and Drug Administration, College Park, Md. Bacteria were grown overnight on brain heart infusion plates (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) at 37°C.

TABLE 1.

Origin and description of reference strains used in this study

| Species | Strain (serotype)a | Sourceb | Microarray identification |

|---|---|---|---|

| L. monocytogenes | LM1250 (NI) | FK | L. monocytogenes |

| L. monocytogenes | CEB2776 (4b) | AH | L. monocytogenes |

| L. monocytogenes | LM1253 (NI) | FK | L. monocytogenes |

| L. monocytogenes | H6900 (1/2a) | CDC | L. monocytogenes |

| L. monocytogenes | SLCC 5957 (NI) | SLCC | L. monocytogenes |

| L. monocytogenes | SE106 (1a) | AH | L. monocytogenes |

| L. monocytogenes | LM37 (NI) | FK | L. monocytogenes |

| L. monocytogenes | F5034 (1/2b) | CDC | L. monocytogenes |

| L. monocytogenes | LM1251 (NI) | FK | L. monocytogenes |

| L. monocytogenes | LM1248 (NI) | FK | L. monocytogenes |

| L. monocytogenes | LM82 (1/2b) | AH | L. monocytogenes |

| L. monocytogenes | LM1249 (NI) | FK | L. monocytogenes |

| L. monocytogenes | LM1252 (NI) | FK | L. monocytogenes |

| L. monocytogenes | LM38 (NI) | FK | L. monocytogenes |

| L. monocytogenes | ATCC 15313 (NI) | ATCC | L. monocytogenes |

| L. monocytogenes | Murray B (4b) | AH | L. monocytogenes |

| L. monocytogenes | Scott A (4b) | AH | L. monocytogenes |

| L. monocytogenes | V37 (4b) | AH | L. monocytogenes |

| L. monocytogenes | ATCC 35152 (3d) | ATCC | L. monocytogenes |

| L. monocytogenes | SE31 (3b) | AH | L. monocytogenes |

| L. monocytogenes | SF-014 (3a) | AH | L. monocytogenes |

| L. ivanovii | ATCC19119 | ATCC | L. ivanovii |

| L. ivanovii | LA29 | AH | L. ivanovii |

| L. ivanovii | SLCC 6965 | AH | L. ivanovii |

| L. ivanovii | SLCC 6966 | AH | L. ivanovii |

| L. ivanovii | SLCC 7926 | AH | L. ivanovii |

| L. ivanovii | SLCC 2379 | AH | L. ivanovii |

| L. ivanovii | SLCC 6032 | AH | L. ivanovii |

| L. ivanovii | F6983 | AH | L. ivanovii |

| L. ivanovii | ATCC 8243 | ATCC | L. ivanovii |

| L. seeligeri | ATCC 35967 | ATCC | L. seeligeri |

| L. seeligeri | SE139 | AH | L. seeligeri |

| L. seeligeri | BS27 | AH | L. seeligeri |

| L. seeligeri | F7295 (1/2b) | AH | L. seeligeri |

| L. seeligeri | F7334 (1/2b) | AH | L. seeligeri |

| L. seeligeri | G906 (1/2b) | AH | L. seeligeri |

| L. seeligeri | SLCC 5921 | AH | L. seeligeri |

| L. seeligeri | F7896 | AH | L. seeligeri |

| L. innocua | ATCC 33090 | ATCC | L. innocua |

| L. innocua | LS027 | AH | L. innocua |

| L. innocua | LA-01 | AH | L. innocua |

| L. innocua | DA-15 | AH | L. innocua |

| L. innocua | 23 | AH | L. innocua |

| L. welshimeri | BA84 | AH | L. welshimeri |

| L. welshimeri | LABSTR | AH | L. welshimeri |

| L. welshimeri | 4889A | AH | L. welshimeri |

| L. welshimeri | LS-156 | AH | L. welshimeri |

| L. welshimeric | SE116 | AH | L. seeligeri |

| L. welshimeric | 2436KA | AH | L. seeligeri |

| L. welshimeric | LS-166 | AH | L. seeligeri |

| L. grayi | ATCC 25401 | ATCC | L. grayi |

| L. grayi | ATCC 19120 | AH | L. grayi |

| L. grayi | 37A | AH | L. grayi |

NI, not identified.

AH, A. Hitchins, Food and Drug Administration; ATCC, American Type Culture Collection; CDC, Centers for Disease Control; FK, F. Khambaty, Food and Drug Administration; SLCC, Special Listeria Culture Collection, Institute of Hygiene and Microbiology, University of Würzburg.

Misidentified strain.

Total DNA preparation.

Freshly grown bacteria were boiled in 1× Tris-EDTA buffer (approximately 108 cells/ml) for 10 min followed by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 10 min to remove denatured proteins and bacterial membranes. The presence of genomic DNA in all prepared samples was confirmed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis followed by staining with ethidium bromide.

Design of microarray oligoprobes.

A BLAST search was used to identify and retrieve the sequences of homologues of each of the six genes analyzed (Table 2). The sequences of the iap gene of L. monocytogenes isolates used in this study were determined by using an ABI Prism 310 genetic analyzer. The sequences were aligned by using ClustalX software (43). Sequences of regions highly conserved among all alleles of each gene were selected to design the gene-specific oligonucleotide probes (oligoprobes) listed in Table 3. The 5′ end of each oligonucleotide was modified during synthesis with TFA Aminolink CE reagent (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) to enable their immobilization on silylated glass slides (CEL Associates, Inc., Houston, Tex.).

TABLE 2.

Accession numbers of the sequences used for the microarray target sequence design

| Gene | Organism | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|

| iap | L. monocytogenes | M80351, AL591975, X52268 |

| L. ivanovii | M80350 | |

| L. innocua | NC_003212, AL596165, M80349 | |

| L. seeligeri | M80353 | |

| L. welshimeri | M80354, M80348 | |

| L. grayi | M80352, M95579 | |

| hly | L. monocytogenes | AF253320, X60035, X15127, M24199 |

| L. ivanovii | X60461 | |

| L. seeligeri | X60462 | |

| inlB | L. monocytogenes | AF121024-AF121047, AL591975, AJ012346, M67471 |

| plcA | L. monocytogenes | U25444, U25447, U25450, U25453, AL591974, X54618, M24199 |

| plcB | L. monocytogenes | AL591974, M82881, X59723 |

| clpE | L. monocytogenes | AL591977, AF076664 |

| L. innocua | AL596167 |

TABLE 3.

Oligonucleotide probes for detection and discrimination among Listeria species

| Type | Name | Sequence | Length (nt) | G+C (%) | Tma (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iap specific | Iap-Mc1 | AGTTGCACCAACACAAGAA | 19 | 42 | 47 |

| Iap-Mc2 | TACTACTCAACAAGCTGCA | 19 | 42 | 47 | |

| Iap-Mc3 | GCCTAAAGTAGCAGAAACG | 19 | 47 | 49 | |

| Iap-Mc4 | ACTACACCTGCGCCTAAA | 18 | 50 | 48 | |

| Iap-Mc5 | TACTACACACGCTGTCAAAA | 20 | 40 | 48 | |

| Iap-Mc6 | CTACACCTGCGCCTAAAGT | 19 | 53 | 51 | |

| Iap-Mc7 | AGTATTATTACGTCCATCAAAG | 22 | 32 | 47 | |

| Iap-Mc8 | CAACCGAATCTAACGGC | 17 | 53 | 47 | |

| Iap-Mc9 | CCAGTAATAGATCAAAATGCTA | 22 | 32 | 47 | |

| Iap-Mc10 | AAAACAAACTACACAAGCAACTA | 23 | 30 | 48 | |

| Iap-Ivan1 | ACTGTTCTTCCTAAAGCGGAA | 21 | 43 | 50 | |

| Iap-Ivan2 | AAGTGCCCCTGCACCAGAA | 19 | 58 | 53 | |

| Iap-Ivan3 | CTGTTACTGCTACTTGG | 17 | 47 | 45 | |

| Iap-Ivan4 | TCCAGTAAATATGGCACTTC | 20 | 40 | 48 | |

| Iap-Ivan5 | TTAGGTACTACTGTAACA | 18 | 33 | 41 | |

| Iap-Ivan6 | AACTGCTTCAACATACACTGTT | 22 | 36 | 49 | |

| Iap-Ivan7 | GTTCAAAACATAATGTCAT | 19 | 26 | 40 | |

| Iap-Ivan8 | TGGTACAAAATTTCATATG | 19 | 26 | 40 | |

| Iap-Ivan9 | AAACAGAAACTCCTGCTGTA | 20 | 40 | 48 | |

| Iap-Ivan10 | CTGCTGAAACGAAACCA | 17 | 47 | 45 | |

| Iap-Wsh1 | GTTAAATGTTCGTTCTGGT | 19 | 37 | 45 | |

| Iap-Wsh2 | CAATAGTATTGTTACTTCCCTAA | 23 | 30 | 48 | |

| Iap-Wsh3 | TCGAAGCAGCTGAATCCAA | 19 | 47 | 49 | |

| Iap-Wsh4 | AAGCAGCTGAATCCAATGG | 19 | 47 | 49 | |

| Iap-Wsh5 | ATAAAATTTCTTATGGCGAAGGAA | 24 | 29 | 49 | |

| Iap-Wsh6 | CTCCTGTTGCTAAACAAGA | 19 | 42 | 47 | |

| Iap-Wsh7 | ATACTAATGCTACTACTCATACT | 23 | 30 | 48 | |

| Iap-Wsh8 | CCCTACTGCTCCAAAAGC | 18 | 56 | 50 | |

| Iap-Wsh9 | GAAACGACAAAACAAACTGCA | 21 | 38 | 49 | |

| Iap-Wsh10 | ACTAAAACAGCACCAGTAGTA | 21 | 38 | 49 | |

| Iap-Innc1 | GACACAACAAGTTAAACCT | 19 | 37 | 45 | |

| Iap-Innc2 | TTGCTACTGAAGAAAAAGCA | 20 | 35 | 46 | |

| Iap-Innc3 | ACCACAGCATTCTTACTTC | 19 | 42 | 47 | |

| Iap-Innc4 | AAAACAACCAACTACACAACAAA | 23 | 30 | 48 | |

| Iap-Innc5 | AACGCTACTACACATAACGTT | 21 | 38 | 49 | |

| Iap-Innc6 | ACTGCTCCTGCACCAAAAG | 19 | 53 | 51 | |

| Iap-Innc7 | TTGACCACAGCATTCTTACTT | 21 | 38 | 49 | |

| Iap-Innc8 | AAAGCAACTAGCACTCCA | 18 | 44 | 46 | |

| Iap-Innc9 | AGTTGTTAAACAAGAAGTGAAA | 22 | 27 | 46 | |

| Iap-Innc10 | GCTACAGAAGCAAAAACAGA | 20 | 40 | 48 | |

| Iap-Seel1 | AGATAATGGCACAACTG | 17 | 41 | 42 | |

| Iap-Seel2 | CATTAAAAAAAGCTAACAAAC | 21 | 24 | 43 | |

| Iap-See13 | AAATCACTTATGGTGAAGG | 19 | 37 | 45 | |

| Iap-See14 | AAAAACAGGCTACGTTAATG | 20 | 35 | 46 | |

| Iap-See15 | AAGTTAAACAAGAGGAAACTA | 21 | 29 | 45 | |

| Iap-See16 | TACACAAGCGGCTCCTG | 17 | 59 | 49 | |

| Iap-See17 | TCCTGCTCAACAAACTAAAAC | 21 | 38 | 49 | |

| Iap-See18 | CAGCAACTACTGAAAAAGATG | 21 | 38 | 49 | |

| Iap-See19 | ATGCAACAACTCATACCGTTAA | 22 | 36 | 49 | |

| Iap-See110 | CTGAAAAAGATGCAGTAGA | 19 | 37 | 45 | |

| Iap-Gry1 | CCATCGGTTGTCTCAGCAA | 19 | 53 | 51 | |

| Iap-Gry2 | ATACAGTGGTTGTCGCATC | 19 | 47 | 49 | |

| Iap-Gry3 | CTCCTGACGCAAATGAAAAAAT | 22 | 36 | 49 | |

| Iap-Gry4 | TTTCCGCTGCTGGAATAG | 18 | 50 | 48 | |

| Iap-Gry5 | CTTCCAAAACTGGTACTAC | 19 | 42 | 47 | |

| Iap-Gry6 | GACCAACTAAAACAACTCAAT | 21 | 33 | 47 | |

| Iap-Gry7 | CTCAATAAACTTGACTCTGAT | 21 | 33 | 47 | |

| Iap-Gry8 | ATCTGACGCAAAAGTCGCT | 19 | 47 | 49 | |

| Iap-Gry9 | TGTCGTTACGAAAGCAGTG | 19 | 47 | 49 | |

| Iap-Gry10 | TTCAAAAATTGATCGAATGGAA | 22 | 27 | 46 | |

| hly specific | Hly-Mc1 | TTTTTCGGCAAAGCTGTTAC | 20 | 40 | 48 |

| Hly-Mc2 | AAACAATAAAAGCAAGCTAGC | 21 | 33 | 47/PICK> | |

| Type | Name | Sequence | Length (nt) | G+C (%) | Tma (°C) |

| Hly-Mc3 | TTTTGATGCTGCCGTAAGT | 19 | 42 | 47 | |

| Hly-Mc4 | TCCTTCAAAGCCGTAATTTAC | 21 | 38 | 49 | |

| Hly-Mc5 | AATCTGTCTCAGGTGATGT | 19 | 42 | 47 | |

| Hly-Mc6 | ACTGGAGCGAAAACAATAAAAGCAAGCTAGC | 31 | 42 | 60 | |

| Hly-Mc7 | AATTATGATCCTGAAGGTAACGAAATTGTTCAAC | 34 | 32 | 58 | |

| Hly-Mc8 | ACTAATTCCCATAGTACTAAAGTAAAAGCTGCT | 33 | 33 | 58 | |

| Hly-Mc9 | ATTTTTCGGCAAAGCTGTTACTAAAGAGCAGTT | 33 | 36 | 59 | |

| Hly-Mc10 | TAAAAGACAATGAATTAGCTGTTATTAAAAAC | 32 | 22 | 53 | |

| Hly-Ivan1 | ATTCTTTGGTAAAAGTGTTAC | 21 | 29 | 45 | |

| Hly-Ivan2 | AAAGAAAACTTGCAAGCGCT | 20 | 40 | 48 | |

| Hly-Ivan3 | TCGTGACATTTTCGTGAAATT | 21 | 33 | 47 | |

| Hly-Ivan4 | TCACACAGCACCAGAGTGA | 19 | 53 | 51 | |

| Hly-Ivan5 | TACTGCATTTAAGGGTAAATC | 21 | 33 | 47 | |

| Hly-Ivan6 | TGAAGGCTGCATTCGATAC | 19 | 47 | 49 | |

| Hly-Ivan7 | GGAGATTTAAGCAAATTACGA | 21 | 33 | 47 | |

| Hly-Ivan8 | CATTTTACGACATCAATCTATTT | 23 | 26 | 46 | |

| Hly-Ivan9 | TATTAATATTCATGCGAAAGAAT | 23 | 22 | 45 | |

| Hly-Ivan10 | TTGCGAGATTCAATGTTACTT | 21 | 33 | 47 | |

| Hly-Seel1 | AACAACTAGATGCTTTAGGTG | 21 | 38 | 49 | |

| Hly-Seel2 | ATGACGAGAACGGAAATGAA | 20 | 40 | 48 | |

| Hly-Seel3 | ATTAACATCTATGCAAGAGAAT | 22 | 27 | 46 | |

| Hly-Seel4 | GAAATGAAATAAAAGTTCATAAGAA | 25 | 20 | 46 | |

| Hly-Seel5 | CAATTTAGGCGAACTTCGAG | 20 | 45 | 50 | |

| Hly-Seel6 | ACTATCCTCTAGCTCGCAT | 19 | 47 | 49 | |

| Hly-Seel7 | GTGGTTATGTAGCCCAATT | 19 | 42 | 47 | |

| Hly-Seel8 | GGTCCACTTATGATAGAGAA | 20 | 40 | 48 | |

| Hly-Seel9 | AGTAACAAAGTTAAAACTGCTTT | 23 | 26 | 46 | |

| Hly-Seel10 | TCGAGGCGGCGATGAGTGG | 16 | 68 | 58 | |

| inlB specific | InlB1 | ATGGGAGAGTAACCCAACCACTGAA | 25 | 48 | 58 |

| InlB2 | GAAAAGCAAAAGCAAGATTTCATGGGAGAG | 30 | 40 | 59 | |

| InlB3 | ACGTTTAACTAAGCTGGATACTTTGTCTC | 29 | 38 | 57 | |

| InlB4 | GACTCCAGAAATAATAAGTGATGATGGC | 28 | 39 | 57 | |

| InlB5 | AATAAGTGATGATGGCGATTATGAAAAACC | 30 | 33 | 56 | |

| InlB6 | CCAAATTAGTGATATTGTGCCACTTG | 26 | 38 | 55 | |

| InlB7 | CAGAAATAATAAGTGATGATGGCGATTATG | 30 | 33 | 56 | |

| InlB8 | TGGAAAGTTTGTATTTGGGAAATAAT | 26 | 27 | 50 | |

| InlB9 | AAATGGCATTTACCAGAATTTATAAAT | 27 | 22 | 49 | |

| InlB10 | TTTAAGTAAGAATCACATAAGCGATTTAAG | 30 | 27 | 53 | |

| plcA specific | PlcA1 | CTAATATCGATGTACCGTATTCCTGCT | 27 | 41 | 57 |

| PlcA2 | CCATGGTAAATGTTGAGATTGTCTTTTGC | 29 | 38 | 57 | |

| PlcA3 | TTTCTTTAAAAATTGAGTAATCGTTTCTAATACA | 34 | 21 | 54 | |

| PlcA4 | CGCATAATAATGGTTTCTTTTGGATTTTTC | 30 | 30 | 55 | |

| PlcA5 | TATCGTTGCTGTTTTGCTCGTCTTTTAAA | 29 | 34 | 56 | |

| PlcA6 | TTGATTAGTGGTTGGATCCGATAATCAAA | 29 | 34 | 56 | |

| PlcA7 | AGTTCTGGGAGTAGTGTAAAAATAATCTTT | 30 | 30 | 55 | |

| PlcA8 | GTAGGGATTTTATTGCTCGTGTCAG | 25 | 44 | 56 | |

| PlcA9 | GTAATAATATTTTTCCGCGGACATCTTTTA | 30 | 30 | 55 | |

| PlcA10 | AATGGCTTTTTTGTGTGGTTCTCTGAAA | 28 | 36 | 56 | |

| plcB specific | PlcB1 | AATATCATACCCTCCAGGCTACCACT | 26 | 46 | 58 |

| PlcB2 | AGTCAACCTATGCACGCCAATAATTTT | 27 | 37 | 55 | |

| PlcB3 | GCCTAGCAATCCATTATTATACGGATATT | 29 | 34 | 56 | |

| PlcB4 | GAAATTTGACACAGCGTTTTATAAATTAG | 29 | 28 | 53 | |

| PlcB5 | ATTTCAATCAATCGGTGACTGATTACCGA | 29 | 38 | 57 | |

| PlcB6 | GCTAATGCGAAAATAACAGGAGCAAAG | 27 | 41 | 57 | |

| PlcB7 | TGATAGAGATAATACTTATTTGCCGGGTTT | 30 | 33 | 56 | |

| PlcB8 | AGTACATTTTTATCTCATTTTTATAATCCTGATAG | 35 | 23 | 55 | |

| PlcB9 | ATGCGGATCATAAAAATCCATATTATGATACT | 32 | 28 | 55 | |

| PlcB10 | GATAAACAAATAGCTCAAGGAATATATGATG | 31 | 29 | 55 | |

| clpE specific | ClpEm1 | CTTACTTTTTTTATAAAAAAAACGCCCCTATA | 32 | 25 | 54 |

| ClpEm2 | GTAAGGCTGCGAGTAACAAAAACGCA | 26 | 46 | 58 | |

| Type | Name | Sequence | Length (nt) | G+C (%) | Tma (°C) |

| ClpEm3 | GATAAATATAGCATAAGTAGGCTTGGAC | 28 | 36 | 56 | |

| ClpEm4 | ACGAGCGAAGCGACAAAGATACCAAT | 26 | 46 | 58 | |

| ClpEm5 | GATACCAATAATCGCTGCAAAATTGC | 26 | 38 | 55 | |

| ClpEm6 | CTCCCGGGATGATGGCAACGATAA | 24 | 54 | 59 | |

| ClpEm7 | GCAACGATAAGTAGTAGCCAAATTATC | 27 | 37 | 55 | |

| ClpEm8 | CATAATAACGCTGCAAAAACATTCGAGAA | 29 | 34 | 56 | |

| ClpEm9 | TAGCCAAATTATCAAAGAATGCGTCGAA | 28 | 36 | 56 | |

| ClpEm10 | ATGATATTCCATACGAGCGAAGCGA | 25 | 44 | 56 | |

| QC | QCprb | TTGGCAGAAGCTATGAAACGATATGGG | 27 | 44 | 58 |

| Cy3-QC | CCCATATCGTTTCATAGCTTCTGCCA | 26 | 46 | 58 |

Basic melting temperature (Tm) was calculated with the Oligonucleotide Properties Calculator (http://www.basic.nwu.edu/biotools/oligocalc.html).

Microchip design and fabrication.

Each bacterial gene was identified by hybridization with 10 independent oligonucleotides (Table 3) covering entire DNA amplicons. Oligoprobes specific for each gene were spotted on individual rows of the array. Marker spots for array positioning on the slide were made by using 1× spotting solution (ArrayIt, Sunnyvale, Calif.) in 0.25 M acetic acid.

Microchips were printed with the PIXSYS 5500 contact microspotting robotic system (Cartesian Technologies, Inc., Calif.) equipped with a microspotting pin (CMP7; ArrayIt). The average size of spots was 250 μm. The spotting solution contained a mixture of specific oligonucleotide probe (80 μM) and quality control (QC) oligonucleotide (8 μM) in 50% dimethyl sulfoxide. Printed slides were dried for at least 20 min at 80°C and treated for 15 min with a freshly prepared 0.25% NaBH4 solution in water. Slides were washed once for 5 min with 0.2% sodium dodecyl sulfate in water and five times for 1 min each with distilled water to remove unbound oligonucleotides.

PCR amplification.

Table 4 lists the primers used to amplify genes for different Listeria virulence factors. The standard PCR mixture (30 μl) contained 1.5 U of HotStarTaq DNA polymerase, 1× reaction buffer supplemented with 2.5 mM MgCl2 (Qiagen, Chatsworth, Calif.), 600 nM (each) forward and reverse primers, a 200 μM concentration of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dATP, dGTP, dCTP, and dTTP), and 1 to 2 μl of DNA template (approximately 0.2 μg of bacterial DNA). PCR was performed with a Gene Amp PCR system 9700 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) with the following conditions: initial activation at 95°C for 15 min, 40 cycles at 94°C for 20 s, 60°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 50 s, and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. The PCR products were separated by electrophoresis in 2% agarose gels containing 1× Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer and visualized by staining with ethidium bromide.

TABLE 4.

Primers used for amplification of various Listeria genes

| Primer | Nucleotide sequence (5′-3′) | Target gene | GenBank accession no. | PCR product size (bp) | Tmf (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LisF | ATGAATATGAAAAAAGCAACKATC | iap | M80351, M80350, M80349, M80353, M80354, M80352 | 644,a 707,b 713,c 716d | 47-49 |

| LisR | ACATARATIGAAGAAGAAGAWARATTATTCCA | 52-55 | |||

| IsoF | GTTAATGAACCTACAAGHCCTTCC | hly | AF253320, X60461, X60462 | 708 | 54-56 |

| IsoR | AACCGTTCTCCACCATTCCCA | 54 | |||

| PlcBF | GATAACCCGACAAATACTGACGTAAATAC | plcB | AL591977, AL591974 | 503 | 57 |

| PlcBR | TCATCTGAGCAAAATCTTTTTGCTACCATGTC | 59 | |||

| ClpEF | CTCCTTTTAAAAATGAGAAATGAAAGGTCTTG | clpE | AL596167 | 517,e 518f | 57 |

| ClpER | TTAAAGTAATGCCAGGCGGTCTAGAACATTC | 60 | |||

| InlBF | AATCACTTTCTTTGGAGCATAATGGTATAAGTG | inlB | AF121047 | 562 | 58 |

| InlBR | GTTCCATCAACATCATAACTTACTGTGTAAACC | 59 | |||

| PlcAF | AAGTTGAGTACGAAYTGCTCTACTTTGTTG | plcA | U25453 | 600 | 58-59 |

| PlcAR | AACACAAACGATGTCATTGTACCAACAACTAG | 59 |

L. grayi.

L. ivanovii and L. welshimeri.

L. seeligeri.

L. innocua.

L. monocytogenes.

Tm, melting temperature.

Synthesis of Cy5-labeled ssDNA.

Single-stranded-DNA (ssDNA) samples for microarray assay were synthesized by using 40 cycles of the primer extension reaction driven by Taq polymerase in the presence of only reverse primers for amplification of six virulence factor genes (Table 4). The reaction was performed in a volume of 50 μl containing 10 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), 1× reaction buffer with 3.0 mM MgCl2, 600 nM (each) reverse primer, 200 nM dGTP, dATP, and dTTP, 40 nM dCTP, 40 nM Cy5-dCTP, and 2 to 4 μl of double-stranded DNA template from the first round of multiplex PCR purified using QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen). The protocol included an initial activation step at 95°C for 1 min followed by 40 cycles at 94°C for 20 s, 58°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 2 min, with a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min. The fluorescently labeled ssDNA products were purified from nonincorporated reagents with a QIAquick PCR purification kit according to the manufacturer's protocol, dried in a vacuum, and solubilized in 10 μl of water.

Hybridization conditions.

Hybridization of the fluorescently labeled ssDNA samples to the microarray was performed in 1× hybridization buffer composed of 5× Denhardt's solution, 6× SSC buffer (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate), and 0.1% Tween 20 at 45°C for 30 min. Before hybridization, 1 μl of the Cy5-labeled ssDNA sample was mixed with equal volume of 2× hybridization buffer containing 0.1 μM Cy3-labeled QC probe (Table 3), followed by denaturing at 95°C for 1 min and chilling on ice. Each sample was placed on the microchip and covered with a 5- by 5-mm plastic coverslip to prevent evaporation of the probe during incubation. After hybridization, the slides were washed once for 1 min with 6× SSC containing 0.2% Tween 20, three times for 1 min with 6× SSC buffer, twice with 2× SSC buffer, and once with 1× SSC buffer and dried in a stream of air.

Microarray scanning.

Fluorescent images of the microarrays were obtained by scanning the slides with ScanArray 5000 (Perkin-Elmer, Boston, Mass.). The fluorescent signals from each spot were measured and compared by using QuantArray software (Perkin-Elmer, Boston, Mass.). Fluorescent signals that differed from the average background at a statistically significant level (P < 0.01) were considered positive.

Sequencing.

In some cases, sequences of the iap gene for some L. monocytogenes strains were determined experimentally. The PCR-amplified DNA fragments were purified by electrophoresis in an agarose gel, extracted with a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol, and sequenced by using the ABI Prism 310 genetic analyzer system (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

GenBank accession numbers of the deposited sequences are AF500174 (strain F5034), AF500175 (strain LM1250), AF500176 (strain SLCC5957), AF500177 (strain CEB2776), AF500178 (strain LM1248), AF500179 (strain LM82), AF500180 (strain LM1249), AF500181 (strain LM1252), AF500182 (strain SE106), AF500183 (strain LM1253), AF500184 (strain H9600), AF500185 (strain LM37), and AF50018 (strain LM38).

RESULTS

Species identification based on the iap gene sequence.

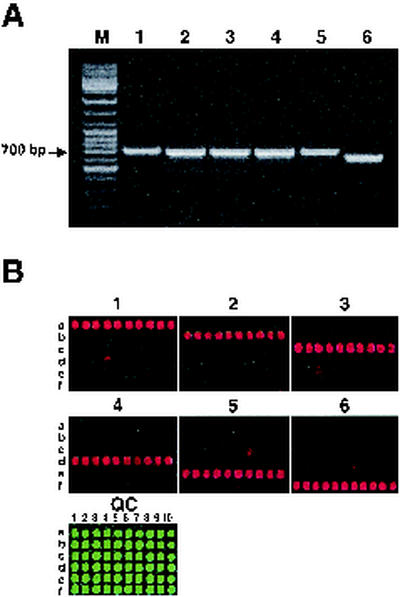

The two universal PCR primers, LisF and LisR (Table 4), recognizing conserved sequences of the iap gene, amplified this gene from all six Listeria species (Fig. 1A). The size of the PCR product generated with these primers varied from 644 to 716 bp depending on the species (Table 4).

FIG. 1.

Species identification based on differences in iap gene sequences. Genomic DNAs of six reference strains were amplified by using universal iap-specific primers followed by separation of PCR products in a 1.5% agarose gel (A). Lanes: M, 100-bp DNA ladder mix; 1, L. monocytogenes (H9600 strain); 2, L. ivanovii (ATCC 19119); 3, L. welshimeri (LABSTR strain); 4, L. innocua (ATCC 33090); 5, L. seeligeri (ATCC 35967); 6, L. grayi (ATCC 25401). Species-specific DNAs were hybridized with the iap microchip (B) containing individual oligonucleotides specific to L. monocytogenes (row a), L. ivanovii (row b), L. welshimeri (row c), L. innocua (row d), L. seeligeri (row e), and L. grayi (row f). Microarray image panels are numbered in accordance with the species numeration in Fig. 1A. QC, Cy3 microarray QC image (see Materials and Methods). For panel QC, 10 individual species-specific oligoprobes were spotted on each row and labeled 1 through 10.

The presence of multiple species-specific sequences within the selected region of the iap gene enabled us to design 10 individual oligoprobes (Table 3) per species.

As shown in Fig. 1B, all designed oligoprobes hybridized with homologous DNA, although in some cases, sporadic and low cross-hybridization with the single oligoprobes of heterologous species was observed (e.g., L. innocua spot 7 with L. seeligeri samples or L. seeligeri spot 3 with L. innocua samples [Fig. 1B, panels 5 and 3, respectively]).

Identification of hemolytic Listeria species.

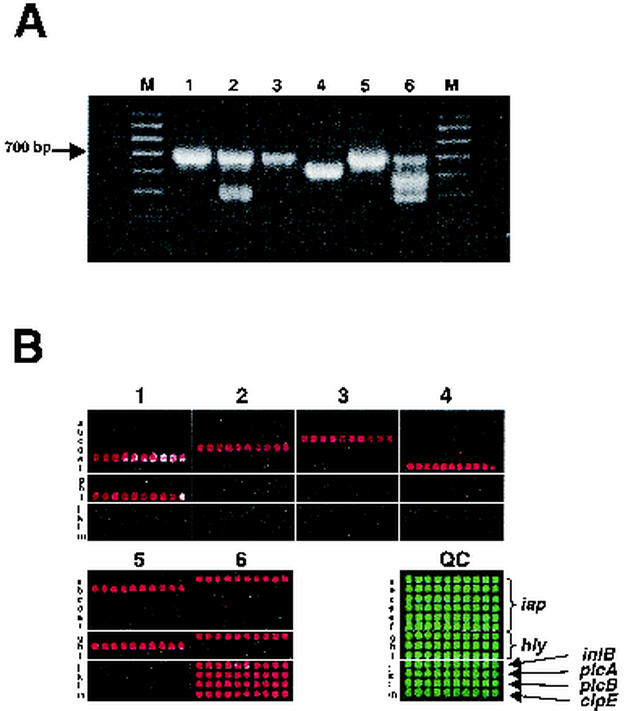

As with the iap gene, conserved sequences within hly were used to design a pair of universal primers, IsoF and IsoR, for amplification of the 708-bp DNA segment from any hemolytic Listeria strain. The primers enabled us to amplify the segment from each of the hemolytic species (Fig. 2A, lanes 1 to 3) but, as expected, did not amplify any DNA from nonhemolytic Listeria species (Fig. 2A, lanes 4 to 6). The genetically divergent region within the amplicons was used to design 10 individual oligoprobes for discriminating between the three species (Table 3). All the probes specifically recognized Cy5-labeled fluorescent samples only from hemolytic species (Fig. 2B). No cross hybridization between amplicons from L. monocytogenes, L. ivanovii, or L. seeligeri was detected.

FIG. 2.

Identification of hemolytic Listeria species. The DNAs of six reference strains were amplified by using universal hly-specific primers and separated in a 1.5% agarose gel (A). Lanes: M, 100-bp DNA ladder mix; 1, L. monocytogenes (H9600 strain); 2, L. ivanovii (ATCC 19119); 3, L. seeligeri (ATCC 35967); 4, L. welshimeri (LABSTR strain); 5, L. innocua (ATCC 33090); 6, L. grayi (ATCC 25401). (B) Hybridization images of amplified DNAs with the hly microchip. Oligonucleotides were specific to L. monocytogenes (a), L. ivanovii (b), and L. seeligeri (c). Microarray image panels are numbered in accordance with the species numbering in panel A. For panel QC, 10 individual species-specific oligoprobes were spotted on each row and labeled 1 through 10.

Microarray analysis of L. monocytogenes-specific virulence factors.

The sequences of all PCR primers and probes for the virulence factors inlB, plcA, plcB, and clpE, specific only for L. monocytogenes (20), are summarized in Tables 4 and 3, respectively. The primers ClpEF and ClpER, selected for amplification of the clpE gene of L. monocytogenes (Table 4), also amplified the fragment from another species, L. innocua (Fig. 3A, lane 2). However, the PCR product from L. innocua did not hybridize to L. monocytogenes-specific probes of the microarray (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Identification of Listeria species using the universal Listeria microchip. Bacterial DNAs were amplified by one-tube multiplex PCR (A) and analyzed by microarray assay (B). The multiplex PCR was performed in the presence of the iap-, hly-, inlB-, plcA-, plcB-, and cplE-specific primers. Lanes: M, 100-bp DNA ladder; 1, L. seeligeri (ATCC 35967); 2, L. innocua (ATCC 33090); 3, L. welshimeri (BA84 strain); 4, L. grayi (ATCC 25401); 5, L. ivanovii (ATCC 19119); 6, L. monocytogenes (LM82 strain). Rows a to f contain iap-specific oligonucleotides (identical to Fig. 1B), rows g to i contain hly-specific oligonucleotides (identical to Fig. 2B), and rows j to m contain oligonucleotides specific to the other four L. monocytogenes virulence factors. Microarray image panels are numbered in accordance with the species numbering in panel A. QC, composition microarray for Listeria species identification.

Simultaneous microarray analysis of Listeria virulence factors using multiplex PCR.

To simplify microarray identification, detection, and analysis of Listeria species using the virulence factors described above (iap, hly, inlB, plcA, plcB, and clpE), we amplified all six genes in a single multiplex PCR.

The Listeria strains listed in Table 1 were tested by using the multiplex PCR followed by hybridization with the “universal” Listeria microchip containing the probes for all six virulence factor genes. Results of the microarray analysis showed that DNA from each Listeria species hybridized only with homologous probes (representative data are shown in Fig. 3B). We found that the use of more than one gene for characterizing pathogenic Listeria species might reduce bacterial misidentification associated with genomic instability. Three strains, SE116, 2436KA, and LS-166, previously characterized as L. welshimeri (Table 1) were identified by microarray as L. seeligeri on the basis of hybridization with the iap-specific oligonucleotides. However, these strains did not hybridize with L. seeligeri hly-specific oligonucleotides. The direct sequencing of the iap, prfA, and 16S rRNA genes of these strains showed that these three strains belonged to L. seeligeri but lost the hly gene due to a deletion (about 6,000 bp) in the central virulence gene cluster (LIPI-1) (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In this paper, we describe the use of oligonucleotide microarray hybridization for the rapid detection and identification of six species of the genus Listeria: L. monocytogenes, L. ivanovii, L. innocua, L. welshimeri, L. seeligeri, and L. grayi. Sequence analysis of different virulence factor genes and bacterial genetic markers previously used for characterization and discrimination among Listeria species allowed us to select two of them, iap and hly, as the most suitable for development of the microarray-based assay. The first gene, iap, encodes the 60-kDa secreted invasion-associated protein p60 (26). Homologues of this gene have been found in all Listeria species (8). Previously, the iap gene was successfully used for Listeria species discrimination by methods based on PCR (6, 7). Minor differences in the sequences of L. monocytogenes serovars can also be used for their identification using restriction enzyme-PCR (11). Another gene selected, hly, encodes a virulence factor that is involved in release of Listeria from primary phagosomes of host cells (5). This gene is specific only to L. monocytogenes, L. ivanovii, and L. seeligeri and can be used for distinguishing among clinically important serotypes of L. monocytogenes (46). However, in the present study we did not pursue the determination of L. monocytogenes types, and serotype-specific oligonucleotides for the iap and hly genes were not included in the microchip.

The last four genes, inlB, plcA, plcB, and clpE, were included in the microarray to verify the identity of L. monocytogenes.

Some genetic markers, including rRNA and 16S-23S rRNA intergenic spacers, previously used for distinguishing among Listeria species (18, 21, 36), were found to be highly conserved among Listeria species and unsuitable for development of multiple oligoprobes for microarray-based discrimination. Other genes, like prfA and actA (45), were not included in the assay because they are missing from some Listeria species or are highly divergent, making it difficult to select universal primers for PCR amplification.

Thus, our approach is based on identification of six virulence factor genes in the bacterial chromosome: iap, hly, inlB, plcA, plcB, and clpE. These factors were simultaneously amplified by one-tube multiplex PCR in the presence of primers for all six genes. Listeria species were discriminated on the basis of the hybridization profile of the fluorescent DNA sample with the universal Listeria microarray, which contained immobilized species-specific oligoprobes.

Microarray hybridization has the potential to become the most efficient approach for rapid PCR-based detection and characterization of viral and bacterial contamination in a variety of samples, including food products. The PCR by itself is a very sensitive method and allows the amplification of single DNA molecules. However, the sensitivity and specificity of PCR amplification tend to be inversely related, such that DNA generated in a highly sensitive PCR assay often contains nonspecific products which complicate the interpretation of the electrophoresis data (17). Although gel electrophoresis, usually used for the analysis of PCR products, is simple and quick, it is often inadequate for accurate characterization of multiple PCR products. In addition, species-specific PCR primers occasionally fail to amplify DNA from a particular isolate if there is a spontaneous mutation(s) in the primer-binding site. However, it may be possible to avoid these shortcomings and improve PCR-based genotyping significantly by replacing gel electrophoresis analysis of PCR products by DNA-DNA hybridization in microarray format. Firstly, the specificity of DNA-DNA hybridization allows the unambiguous detection of target sequences regardless of the potential presence of nonspecific DNA products. Secondly, microarray technology permits the use of universal degenerate primers capable of amplifying all the genetic variants of the target gene(s), thereby increasing the sensitivity and efficiency of the assay. Thirdly, the miniature size of the microarray enables simultaneous analysis of a large number of the genetic markers in one experiment. Fourthly, the use of multiple oligonucleotides for each target gene increases the certainty of detection and discrimination between closely related species. Therefore, species can be identified by recognizing the hybridization pattern of bacterial DNA with species-specific microarray probes. Moreover, hybridization with short oligonucleotides (20 to 25 nucleotides) is sensitive enough to detect a single nucleotide mismatch between the template DNA and the oligoprobes, thus allowing one to monitor minor genetic variability of target genes in a bacterial population.

In previous studies (9, 10) in which DNA samples were labeled with fluorescent dyes during PCR amplification, it was found that in order to maximize assay sensitivity, the labeling step and PCR step should be separated. The presence of Cy5(3)-dCTP was observed to diminish the yield of the PCR products. Therefore, in the present study, we replaced the method of ssDNA synthesis with a primer extension of DNA synthesized in the first round of PCR. This approach ensured adequate quantity and quality of fluorescent ssDNA and enabled unambiguous identification of DNA by microarray hybridization even in cases where we failed to detect the presence of the respective PCR product by gel electrophoresis (data not shown).

The approach described in this study is one of the first attempts to use oligonucleotide microarray technology combined with PCR amplification for monitoring the safety of the food supply. It is noteworthy that previously developed PCR-based protocols for bacterial identification can be easily adapted to take advantage of the specificity and speed of microarray hybridization to produce powerful tools for rapid, high-throughput screening and accurate genotyping of a variety of viral and bacterial pathogens.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from USDA, funding from FDA office of science awarded to V. Chizhikov and A. Rasooly, and a grant from the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Project Agency (DARPA) to K. Chumakov.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allerberger, F., M. Dierich, G. Petranyi, M. Lalic, and A. Bubert. 1997. Nonhemolytic strains of Listeria monocytogenes detected in milk products using VIDAS immunoassay kit. Zentralbl. Hyg. Umweltmed. 200:189-195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bansal, N. S., F. H. McDonell, A. Smith, G. Arnold, and G. F. Ibrahim. 1996. Multiplex PCR assay for the routine detection of Listeria in food. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 33:293-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beuchat, L. R., and J. H. Ryu. 1997. Produce handling and processing practices. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 3:459-465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bind, J. L., C. Avoyne, and J. Delaval. 1996. Critical analysis of isolation, counting and identification methods of Listeria in food industry. Pathol. Biol. (Paris) 44:757-768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brunt, L. M., D. A. Portnoy, and E. R. Unanue. 1990. Presentation of Listeria monocytogenes to CD8+ T cells requires secretion of hemolysin and intracellular bacterial growth. J. Immunol. 145:3540-3546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bubert, A., I. Hein, M. Rauch, A. Lehner, B. Yoon, W. Goebel, and M. Wagner. 1999. Detection and differentiation of Listeria spp. by a single reaction based on multiplex PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:4688-4692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bubert, A., S. Kohler, and W. Goebel. 1992. The homologous and heterologous regions within the iap gene allow genus- and species-specific identification of Listeria spp. by polymerase chain reaction. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:2625-2632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bubert, A., M. Kuhn, W. Goebel, and S. Kohler. 1992. Structural and functional properties of the p60 proteins from different Listeria species. J. Bacteriol. 174:8166-8171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chizhikov, V., A. Rasooly, K. Chumakov, and D. D. Levy. 2001. Microarray analysis of microbial virulence factors. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3258-3263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chizhikov, V., M. Wagner, A. Ivshina, Y. Hoshino, A. Z. Kapikian, and K. Chumakov. 2002. Detection and genotyping of human group A rotaviruses by oligonucleotide microarray hybridization. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2398-2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Comi, G., L. Cocolin, C. Cantoni, and M. Manzano. 1997. A RE-PCR method to distinguish Listeria monocytogenes serovars. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 18:99-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooray, K. J., T. Nishibori, H. Xiong, T. Matsuyama, M. Fujita, and M. Mitsuyama. 1994. Detection of multiple virulence-associated genes of Listeria monocytogenes by PCR in artificially contaminated milk samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:3023-3026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curtis, G. D., and W. H. Lee. 1995. Culture media and methods for the isolation of Listeria monocytogenes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 26:1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dalton, C. B., C. C. Austin, J. Sobel, P. S. Hayes, W. F. Bibb, L. M. Graves, B. Swaminathan, M. E. Proctor, and P. M. Griffin. 1997. An outbreak of gastroenteritis and fever due to Listeria monocytogenes in milk. N. Engl. J. Med. 336:100-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donnelly, C. W. 1988. Historical perspectives on methodology to detect Listeria monocytogenes. J. Assoc. Off. Anal. Chem. 71:644-646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eld, K., M. L. Danielsson-Tham, A. Gunnarsson, and W. Tham. 1993. Comparison of a cold enrichment method and the IDF method for isolation of Listeria monocytogenes from animal autopsy material. Vet. Microbiol. 36:185-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elnifro, E. M., A. M. Ashshi, R. J. Cooper, and P. E. Klapper. 2000. Multiplex PCR: optimization and application in diagnostic virology. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13:559-570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emond, E., I. Fliss, and S. Pandian. 1993. A ribosomal DNA fragment of Listeria monocytogenes and its use as a genus-specific probe in an aqueous-phase hybridization assay. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:2690-2697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernandez-Garayzabal, J. F., M. Blanco, J. A. Vazquez-Boland, V. Briones, J. A. Garcia, C. Delgado, M. Domingo, J. Marco, and L. Dominguez. 1992. A direct plating method for monitoring the contamination of Listeria monocytogenes in silage. Zentralbl. Veterinarmed. 39:513-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glaser, P., L. Frangeul, C. Buchrieser, C. Rusniok, A. Amend, F. Baquero, P. Berche, H. Bloecker, P. Brandt, T. Chakraborty, A. Charbit, F. Chetouani, E. Couve, A. de Daruvar, P. Dehoux, E. Domann, G. Dominguez-Bernal, E. Duchaud, L. Durant, O. Dussurget, K. D. Entian, H. Fsihi, F. G. Portillo, P. Garrido, L. Gautier, W. Goebel, N. Gomez-Lopez, T. Hain, J. Hauf, D. Jackson, L. M. Jones, U. Kaerst, J. Kreft, M. Kuhn, F. Kunst, G. Kurapkat, E. Madueno, A. Maitournam, J. M. Vicente, E. Ng, H. Nedjari, G. Nordsiek, S. Novella, B. de Pablos, J. C. Perez-Diaz, R. Purcell, B. Remmel, M. Rose, T. Schlueter, N. Simoes, A. Tierrez, J. A. Vazquez-Boland, H. Voss, J. Wehland, and P. Cossart. 2001. Comparative genomics of Listeria species. Science 294:849-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graham, T. A., E. J. Golsteyn-Thomas, J. E. Thomas, and V. P. Gannon. 1997. Inter- and intraspecies comparison of the 16S-23S rRNA operon intergenic spacer regions of six Listeria spp. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 47:863-869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hacia, J. G., J. B. Fan, O. Ryder, L. Jin, K. Edgemon, G. Ghandour, R. A. Mayer, B. Sun, L. Hsie, C. M. Robbins, L. C. Brody, D. Wang, E. S. Lander, R. Lipshutz, S. P. Fodor, and F. S. Collins. 1999. Determination of ancestral alleles for human single-nucleotide polymorphisms using high-density oligonucleotide arrays. Nat. Genet. 22:164-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ingianni, A., M. Floris, P. Palomba, M. A. Madeddu, M. Quartuccio, and R. Pompei. 2001. Rapid detection of Listeria monocytogenes in foods, by a combination of PCR and DNA probe. Mol. Cell. Probes 15:275-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacquet, C., D. Thierry, P. Veit, J. L. Guesdon, and J. Rocourt. 1999. Evaluation of an rDNA Listeria probe for Listeria monocytogenes typing. APMIS 107:624-630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katsuda, K., M. Iguchi, T. Tuboi, K. Nishimori, K. Tanaka, I. Uchida, and M. Eguchi. 2000. Rapid molecular typing of Listeria monocytogenes by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Res. Vet. Sci. 69:99-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuhn, M., and W. Goebel. 1989. Identification of an extracellular protein of Listeria monocytogenes possibly involved in intracellular uptake by mammalian cells. Infect. Immun. 57:55-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee, W. H., and D. McClain. 1986. Improved Listeria monocytogenes selective agar. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 52:1215-1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lovett, J. 1988. Isolation and identification of Listeria monocytogenes in dairy products. J. Assoc. Off. Anal. Chem. 71:658-660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McClain, D., and W. H. Lee. 1988. Development of USDA-FSIS method for isolation of Listeria monocytogenes from raw meat and poultry. J. Assoc. Off. Anal. Chem. 71:660-664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Norton, D. M., J. M. Scarlett, K. Horton, D. Sue, J. Thimothe, K. J. Boor, and M. Wiedmann. 2001. Characterization and pathogenic potential of Listeria monocytogenes isolates from the smoked fish industry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:646-653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pangallo, D., E. Kaclikova, T. Kuchta, and H. Drahovska. 2001. Detection of Listeria monocytogenes by polymerase chain reaction oriented to inlB gene. New Microbiol. 24:333-339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pastinen, T., M. Raitio, K. Lindroos, P. Tainola, L. Peltonen, and A. C. Syvanen. 2000. A system for specific, high-throughput genotyping by allele-specific primer extension on microarrays. Genome Res. 10:1031-1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raitio, M., K. Lindroos, M. Laukkanen, T. Pastinen, P. Sistonen, A. Sajantila, and A. C. Syvanen. 2001. Y-chromosomal SNPs in Finno-Ugric-speaking populations analyzed by minisequencing on microarrays. Genome Res. 11:471-482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ripabelli, G., J. McLauchin, and E. J. Threlfall. 2000. Amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) analysis of Listeria monocytogenes. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 23:132-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saito, A., T. Sawada, F. Ueda, and R. Hondo. 1998. Classification of Listeria monocytogenes by PCR-restriction enzyme analysis in the two genes of hlyA and iap. New Microbiol. 21:87-92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sallen, B., A. Rajoharison, S. Desvarenne, F. Quinn, and C. Mabilat. 1996. Comparative analysis of 16S and 23S rRNA sequences of Listeria species. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 46:669-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schena, M., D. Shalon, R. W. Davis, and P. O. Brown. 1995. Quantitative monitoring of gene expression patterns with a complementary DNA microarray. Science 270:467-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schena, M., D. Shalon, R. Heller, A. Chai, P. O. Brown, and R. W. Davis. 1996. Parallel human genome analysis: microarray-based expression monitoring of 1000 genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:10614-10619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schlech, W. F. 1996. Pathogenesis and immunology of Listeria monocytogenes. Pathol. Biol. (Paris) 44:775-782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schlech, W. F., III. 2000. Foodborne listeriosis. Clin. Infect Dis. 31:770-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Siegman-Igra, Y., R. Levin, M. Weinberger, Y. Golan, D. Schwartz, Z. Samra, H. Konigsberger, A. Yinnon, G. Rahav, N. Keller, N. Bisharat, J. Karpuch, R. Finkelstein, M. Alkan, Z. Landau, J. Novikov, D. Hassin, C. Rudnicki, R. Kitzes, S. Ovadia, Z. Shimoni, R. Lang, and T. Shohat. 2002. Listeria monocytogenes infection in Israel and review of cases worldwide. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:305-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swaminathan, B., S. B. Hunter, P. M. Desmarchelier, P. Gerner-Smidt, L. M. Graves, S. Harlander, R. Hubner, C. Jacquet, B. Pedersen, K. Reineccius, A. Ridley, N. A. Saunders, and J. A. Webster. 1996. W. H. O.-sponsored international collaborative study to evaluate methods for subtyping Listeria monocytogenes: restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis using ribotyping and Southern hybridization with two probes derived from L. monocytogenes chromosome. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 32:263-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tran, H. L., and S. Kathariou. 2002. Restriction fragment length polymorphisms detected with novel DNA probes differentiate among diverse lineages of serogroup 4 Listeria monocytogenes and identify four distinct lineages in serotype 4b. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:59-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vazquez-Boland, J. A., M. Kuhn, P. Berche, T. Chakraborty, G. Dominguez-Bernal, W. Goebel, B. Gonzalez-Zorn, J. Wehland, and J. Kreft. 2001. Listeria pathogenesis and molecular virulence determinants. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:584-640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vines, A., and B. Swaminathan. 1998. Identification and characterization of nucleotide sequence differences in three virulence-associated genes of Listeria monocytogenes strains representing clinically important serotypes. Curr. Microbiol. 36:309-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wernars, K., P. Boerlin, A. Audurier, E. G. Russell, G. D. Curtis, L. Herman, and N. van der Mee-Marquet. 1996. The W. H. O. multicenter study on Listeria monocytogenes subtyping: random amplification of polymorphic DNA (RAPD). Int. J. Food Microbiol. 32:325-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Winters, D. K., T. P. Maloney, and M. G. Johnson. 1999. Rapid detection of Listeria monocytogenes by a PCR assay specific for an aminopeptidase. Mol. Cell. Probes 13:127-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]