Abstract

Differences in the presence of nine urovirulence factors among clinical isolates of Escherichia coli causing cystitis and pyelonephritis in women and prostatitis in men have been studied. Hemolysin and necrotizing factor type 1 occur significantly more frequently among isolates causing prostatitis than among those causing cystitis (P < 0.0001) or pyelonephritis (P < 0.005). Moreover, the papGIII gene occurred more frequently in E. coli isolates associated with prostatitis (27%) than in those associated with pyelonephritis (9%) (P < 0.05). Genes encoding aerobactin and PapC occurred significantly less frequently in isolates causing cystitis than in those causing prostatitis (P < 0.01 and P < 0.0001, respectively) and pyelonephritis (P < 0.01 and P < 0.0001, respectively). No differences in the presence of Sat or type 1 fimbriae were found. Finally, AAFII and Bfp fimbriae are no longer considered uropathogenic virulence factors since they were not found in any of the strains analyzed. Overall, the results showed that clinical isolates producing prostatitis need greater virulence than isolates producing pyelonephritis in women or, in particular, cystitis in women (P < 0.05). Overall, the results suggest that clinical isolates producing prostatitis are more virulent that those producing pyelonephritis or cystitis in women.

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are one of the most common infectious diseases encountered in the clinical practice, mainly being associated with different members of the family Enterobacteriaceae. In fact, Escherichia coli is by far the most predominant pathogen causing UTIs (4, 18, 19, 21).

In general, rates of UTIs are higher among women than among men (15), with cystitis being the most prevalent UTI in women. It is noteworthy that the prevalence of quinolone resistance among E. coli strains causing cystitis is significantly higher than the prevalence of quinolone resistance among strains causing urinary parenchymatous infections such as prostatitis and pyelonephritis (2, 23). Velasco et al. (23) found that 20% of the isolates causing cystitis were resistant to ciprofloxacin, while only 8% of the invasive isolates causing UTIs had a resistant phenotype. Some studies suggest that resistance to the quinolones may be associated with a diminished virulence of the uropathogenic strains (16). Moreover, in a recent work (25), the prevalence of different genes encoding certain virulence factors among quinolone-resistant E. coli isolates causing cystitis and pyelonephritis in women was found to be lower than that among quinolone-susceptible strains.

Both host and bacterial factors have been associated with the pathogenesis of these infections (9, 21). Thus, uropathogenic strains of E. coli are believed to display a variety of virulence properties that help them colonize host mucosal surfaces and circumvent host defenses to allow invasion of the normally sterile urinary tract (15, 18, 21). A number of virulence determinants have been related to the acquisition or development of UTIs. Among these factors, siderophores, toxins, capsules, fimbriae, and others have been described (1, 6, 11-13, 15, 17, 18, 21, 27). Some of these virulence factors, such as necrotizing factor type 1, α-hemolysin, or the Sat protein (a recently described autotransported protein which acts as a proteolytic toxin), have been found to be located in pathogenicity islands (PAI) (3, 5-7, 13).

Different studies analyzing the prevalence of a number of virulence factors in different UTIs have been performed in the past (1, 10, 11, 17). However, the evolution in the knowledge of UTIs makes it necessary to perform a comparative study of the prevalence of both well-established and putative urovirulence factors in UTIs affecting women and men.

The aim of this study was to analyze the prevalence of nine virulence factors in quinolone-susceptible pathogenic E. coli strains causing invasive UTIs in men (prostatitis) and women (pyelonephritis) and noninvasive UTIs in women (cystitis).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microorganisms.

A total of 111 E. coli strains have been analyzed. Seventy-one isolates (34 causing pyelonephritis in women, and 37 causing prostatitis in men) were submitted to the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory of the Hospital Clinic of Barcelona. The remaining 40 isolates were from women with cystitis and were recovered from urine samples submitted to the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory of the Primary Care Center Manso or the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory of the Hospital Clinic of Barcelona. Only one isolate from each patient was analyzed. Resistance to quinolones was considered an exclusion criterion to avoid the bias produced by the prevalence of certain virulence factors in quinolone-resistant isolates (25).

Cystitis was clinically defined as a syndrome involving dysuria, frequency, and urgency, whereas acute pyelonephritis was defined as a syndrome characterized by fever (armpit temperature, >38°C), flank pain, and/or lumbar tenderness, often associated with dysuria, urgency, and frequency. Prostatitis was defined by the presence of fever, pyuria, and prostatic tenderness.

Antibacterial susceptibility testing.

The susceptibilities of the isolates tested to nalidixic acid and ciprofloxacin were established by the E-test, according to the instructions of the manufacturer (AB-Biodisk, Sölna, Sweden).

Hemolytic activity.

The isolates were tested for the production of hemolysin on 5% sheep blood agar plates. Strains with a clear halo after overnight culture at 37°C were defined as hemolytic.

Expression of type 1 fimbriae.

The presence of type 1 fimbriae was determined by agglutination of Saccharomyces cerevisiae by the procedure described by Andreu et al. (1).

Detection of genes encoding E. coli urovirulence factors.

The primers listed in Table 1 were used to amplify and detect some genes encoding urovirulence factors. The presence of the cnf1, papC, aer, and hly genes was established by use of the conditions described by Yamamoto et al. (27). The PCR conditions used to amplify a fragment of the prs operon and the sat and fimA genes were those described by Vila et al. (24), although 35 cycles instead of 30 cycles were used. Finally, the conditions described by Vargas et al. (22) and Vila et al. (26) were used to amplify the bfp and aaf genes, respectively. All samples with negative results were retested at least twice to eliminate the possibility of false-negative results. The strains from randomly selected samples with positive PCR results were recovered, and their sequences were determined by using the dRhodamine Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Emeryville, Calif.) and analyzed in an automatic DNA sequencer (ABI Prism 377; Perkin-Elmer Cetus) in order to perform a quality control for the PCR products obtained.

TABLE 1.

Primers and hybridization temperatures used in the amplification reactions for the virulence factors

| Virulence factor | Oligonucleotide sequence (5′-3′) | Annealing temp (°C) | Size (bp) of amplified product | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| papC | GACGGCTGTACTGCAGGGTGTGGCG | 63 | 328 | 27 |

| ATATCCTTTCTGCAGGGATGCAATA | ||||

| cnf1 | AAGATGGAGTTTCCTATGCAGGAG | 63 | 498 | 27 |

| CATTCAGAGTCCTGCCCTCATTATT | ||||

| aer | TACCGGATTGTCATATGCAGACCGT | 63 | 602 | 27 |

| AATATCTTCCTCCAGTCCGGAGAAG | ||||

| hly | AACAAGGATAAGCACTGTTCTGGCT | 63 | 1,177 | 27 |

| ACCATATAAGCGGTCATTCCCGTCA | ||||

| sat | ACTGGCGGACTCATGCTGT | 55 | 387 | 20 |

| AACCCTGTAAGAAGACTGAGC | ||||

| fimA | GTTGTTCTGTCGGCTCTGTC | 55 | 447 | This study |

| ATGGTGTTGGTTCCGTTATTC | ||||

| papGIII | CATTTATCGTCCTCAACTTAG | 55 | 482 | This study |

| AAGAAGGGATTTTGTAGCGTC | ||||

| aafII | TGCGATTGCTACTTTATTAT | 55 | 242 | 26 |

| ATTGACCGTGATTGGCTTCC | ||||

| bfp | ACAAAGATACAACAAACAAAAA | 55 | 260 | 23 |

| TTCAGCAGGAGTAAAAGCAGTC |

Ratio of number of virulence factors per strain.

A ratio consisting of the quotient of the number of virulence factors present in the strains causing cystitis, pyelonephritis, and prostatitis to the total number of strains causing those infections was calculated.

Statistical analysis.

To establish the significance of the results, the Fisher exact test, the chi-square test, or the Kruskal-Wallis test was used as appropriate. The level of significance was set at a P value of <0.05.

RESULTS

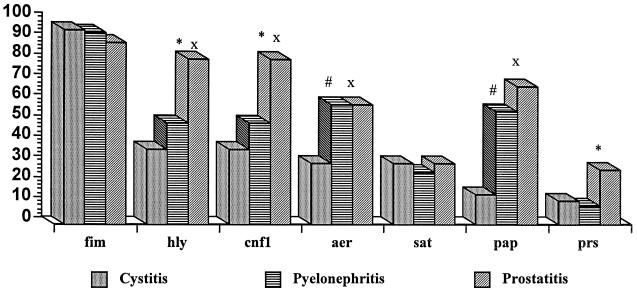

The presence of nine virulence factors in a set of quinolone-susceptible pathogenic E. coli strains causing different UTIs was determined by PCR. The prevalence of these virulence factors is shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Prevalence of genes encoding seven virulence factors in three different UTIs. fim, type 1 fimbriae; hly, hemolysin; cnf1, necrotizing factor type 1; aer, aerobactin; sat, autotransported toxin (Sat); pap, type P fimbriae; prs, type P fimbriae (papGIII). ∗, statistically significant difference between pyelonephritis and prostatitis; x, statistically significant difference between cystitis and prostatitis; #, statistically significant difference between cystitis and pyelonephritis.

The most frequently found virulence factor-encoding gene in the E. coli strains studied, independently of whether the strain caused cystitis, pyelonephritis, or postatitis, was the gene for type 1 fimbriae (prevalence range, 89 to 95%). However, a 100% concordance between the presence of the gene and the expression of the fimbriae was found only among the group of strains causing pyelonephritis. The lowest rate of expression of this virulence factor was among the isolates producing prostatitis, with 85% of the strains that had the gene expressing it. If we take into account all isolates analyzed, only 76% of the isolates producing prostatitis expressed the gene, while 90 and 94% of the isolates producing cystitis and pyelonephritis, respectively, expressed the gene.

In all cases the α-hemolysin- and necrotizing factor type 1-encoding genes were present concomitantly. The genes for these two factors were present at a higher frequency among strains causing prostatitis (being present in 81% of the strains, whereas they were present in only 52 and 37% of the strains causing pyelonephritis [P < 0.005] and cystitis [P < 0.0001], respectively). Only three strains (two strains causing cystitis and another strain causing prostatitis) possessed the gene for α-hemolysin but were unable to express it, while all strains with a hemolytic phenotype had the gene encoding α-hemolysin.

The results show the distributions of type P fimbriae among isolates causing different UTIs. Thus, through the detection of the papC gene, it was observed that type P fimbriae were more prevalent among isolates causing pyelonephritis and prostatitis than among those causing cystitis (P < 0.0001 for both comparisons). The amplification of the papGIII gene showed that it was highly prevalent among isolates causing prostatitis compared with its prevalence among those causing cystitis and pyelonephritis, although a significant difference was observed only for the latter comparison (P < 0.05). The low rate of association between positivity for papC and positivity for papGIII, in particular among isolates causing cystitis, is noteworthy. Thus, only one of five isolates that caused cystitis and that had the papGIII gene was positive for papC. In contrast, there was a 100% association between the presence of the papGIII gene and the presence of genes encoding α-hemolysin and necrotizing factor type 1.

The gene encoding aerobactin was especially prevalent among strains causing pyelonephritis and prostatitis (59% in both cases), whereas it was found in only 30% of the isolates causing cystitis (P < 0.01 in both cases). The gene encoding Sat was present in similar proportions among the strains causing different UTIs, with values of 26 and 30% for strains causing pyelonephritis and cystitis, respectively. In both strains causing pyelonephritis and strains causing prostatitis, the gene encoding Sat was present concomitantly with the gene encoding aerobactin. No strains presenting bfp and AAFII were found.

The results show that the ratio of the number of urovirulence factors analyzed per strain for strains causing cystitis was 2.57 (median, 3), while the ratios for strains causing pyelonephritis and prostatitis were 3.47, and 4.35, respectively (medians, 3 for each disease). By the Kruskal-Wallis test a statistically significant (P < 0.05) difference in the levels of virulence of the strains causing cystitis and pyelonephritis was found.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of nine virulence factors in quinolone-susceptible E. coli isolates causing cystitis, pyelonephritis, and prostatitis has been established. Resistance to quinolones was used as an exclusion criterion since recent studies have shown that quinolone-resistant clinical isolates of E. coli are underrepresented among E. coli isolates causing invasive UTIs (2, 23). Moreover, it has been stated that quinolone resistance may be associated with a selective loss of virulence factors (25). Thus, use of quinolone-resistant isolates causing different UTIs could result in a bias of the results of the prevalence of urovirulence factors obtained.

The high prevalence of type 1 fimbriae is in accordance with previous results from studies conducted by other investigators (11, 14), who have found a high prevalence of type 1 fimbriae among uropathogenic E. coli strains. Some studies (11) indicate that type 1 fimbriae are more important for colonization of the bladder than for colonization of the kidney. Our results showed that the proportions of type 1 fimbriae among isolates producing pyelonephritis and cystitis were equal. However, the rates of expression of this type of fimbria in the present study suggests that this virulence factor has a relatively lower level of importance among the isolates producing prostatitis than among the isolates producing the other two infections analyzed. However, no statistically significant differences were found.

When the strains were analyzed for the presence of the papC gene, the results showed a significantly higher frequency of this gene among strains causing pyelonephritis and prostatitis than among those causing cystitis. In addition, the papGIII gene (Prs fimbriae) was detected at a statistically significant higher frequency among the strains causing prostatitis than among those causing pyelonephritis. This high prevalence of type P fimbriae among isolates causing invasive UTIs compared to that among those causing cystitis is in accordance with results previously reported in the literature (11), being related to an increased tropism for the kidney and prostate. The higher prevalence of the papGIII gene among isolates causing prostatitis than among those causing pyelonephritis has also been described by Mitsumori et al. (17). Although in that study, which included 107 clinical isolates of E. coli causing prostatitis in men and 76 isolates causing pyelonephritis in women, the prevalence of the prs gene among the strains causing prostatitis was 48% (somewhat higher that that found in our study). The prevalence among the isolates causing pyelonephritis in women was 32% (which, again, was higher than that found in our study). Statistical analysis showed a significant difference (P < 0.05). In another study by Jantunen et al. (10), the prevalence of the prs operon was 16.81% among strains causing pyelonephritis in children without significant abnormalities of the urinary tract. In the latter study no difference in prevalence by sex was detected. These differences in the prevalence of the same urovirulence factor may be explained by different geographical prevalences. This fact has recently been stated for another of the virulence factors for which the strains evaluated in the present study were analyzed, the Sat toxin, in a study with isolates of Shigella spp. causing traveler's diarrhea (20).

It is interesting that despite the close relation between the different pap operons, there is no association at all between the papC gene and the papGIII gene in these isolates.

The genes encoding CNF1 and α-hemolysin have been described in the same pathogenicity island containing the prs fimbriae (3). This is in accordance with the 100% association of these two virulence factors in our study. Moreover, the prs operon was always found in strains that also had the genes encoding CNF1 and α-hemolysin. However, some strains with the last two genes did not carry the prs operon. This may be explained by the presence of a pathogenicity island containing the genes encoding CNF1 and α-hemolysin but not the prs operon. In fact, different pathogenicity islands containing diverse combinations of genes encoding virulence factors have been described (3, 7). Our results show a higher prevalence of the genes encoding α-hemolysin and necrotizing factor type 1 among E. coli strains causing prostatitis than among strains causing pyelonephritis and, in particular, those causing cystitis. In fact, these urovirulence factors seem to be the most important virulence factors among the strains causing prostatitis. This fact is in accordance with the results previously reported by Mitsumori et al. (17), who found higher prevalences of the genes encoding α-hemolysin and necrotizing factor type 1 among isolates causing prostatitis (69 and 64%, respectively) than among those causing pyelonephritis (51 and 36%, respectively). It is interesting to note that, in contrast with the above-mentioned work, in our study there was a 100% association between the presence of these two genes.

A higher prevalence of aerobactin was found among isolates causing pyelonephritis and prostatitis than among those causing cystitis. This fact may be related to the increased ability of pathogenic E. coli strains to cause cystitis than to cause invasive UTIs; this is associated with the lower level of virulence required to produce cystitis than to produce pyelonephritis or prostatitis, as shown by analysis of the general virulence of the strains. The presence of a siderophore may be an important factor in the development of pyelonephritis or prostatitis.

Sat is an autotransporter protein which acts as a proteolytic toxin and which has recently been identified in a uropathogenic E. coli isolate (6, 8). In our study the prevalence of this toxin among the different isolates analyzed was low, and the prevalence was similar among the isolates causing the different forms of UTIs, suggesting that this toxin does not play a special role in the development of any of the three pathologies. It has recently been described that the gene encoding Sat resides within PAI II of E. coli CFT073, which also contains genes encoding the aerobactin system (5). This is in accordance with our results, which seem to suggest a certain level of association between the presence of this factor and the presence of aerobactin.

It must be noted that statistically significant associations between the presence of different genes does not necessarily imply a direct linkage on PAI; other reasons may underlie this phenomenon.

None of the strains analyzed had the genes encoding the AAFII and bfp fimbriae. These two fimbriae have been described as diarrhea-associated virulence factors. Thus, AAFII fimbriae have been related to the enteroaggregative E. coli phenotype, while bfp fimbriae have mainly been associated with enteropathogenic E. coli (26).

In general, the results show the higher virulence required for E. coli isolates to produce prostatitis than to produce pyelonephritis and, in particular, cystitis. This fact may be due to the difficulties encountered in reaching the prostate, as it has been stated that the physiology of men makes it more difficult for E. coli to cause UTIs in men than in women (15).

In summary, our results show the higher contents of virulence factors in E. coli clinical isolates causing prostatitis than in those causing pyelonephritis and especially those causing cystitis. Moreover α-hemolysin, necrotizing factor type 1, and Prs fimbriae seem to be especially relevant in isolates causing prostatitis. Further studies are needed both to establish the prevalence of these and other virulence factors in other geographical areas and to corroborate the associations between virulence factors and specific infections detected in the present study.

Acknowledgments

This work was performed thanks to grants FIS00/0632 and FIS00/0997 of the Ministerio de Sanidad of Spain.

We thank Margarita M. Navia for useful suggestions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andreu, A., A. E. Stapleton, C. Fennel, H. A. Lockman, M. Xercavins, F. Fernández, and W. E. Stamm. 1997. Urovirulence determinants in Escherichia coli strains causing prostatitis. J. Infect. Dis. 176:464-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blázquez, R., A. Menasalvas, I. Carpena, C. Ramírez, C. Guerrero, and S. Moreno. 1999. Invasive disease caused by ciprofloxacin-resistant uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 18:503-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blum, G., V. Falbo, A. Caprioli, and J. Hacker. 1995. Gene clusters encoding the cytotoxic necrotizing factor type 1, Prs-fimbriae and α-haemolysin from the pathogenicity island II of the uropathogenic Escherichia coli strain J96. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 126:189-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chomarat, M. 2000. Resistance of bacteria in urinary tract infections. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 16:483-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guyer, D. M., N. W. Gunther IV, and H. L. T. Mobley. 2001. Secreted proteins and other features specific to uropathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Infect. Dis. 183(Suppl. 1):S32-S35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guyer, D. M., I. R. Henderson, J. P. Nataro, and H. L. T. Mobley. 2000. Identification of Sat, an autotransporter toxin produced by uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 38:53-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hacker, J., and J. B. Kaper. 2000. Pathogenicity islands and the evolution of microbes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:641-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henderson, I. R., and J. P. Nataro. 2001. Virulence functions of autotransporter proteins. Infect. Immun. 69:1231-1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hooton, T. M. 2000. Pathogenesis of urinary tract infections: an update. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 46(Suppl. S1):1-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jantunen, M. E., A. Siitonen, O. Koskimies, S. Wikström, U. M. Kärkkäinen, E. Salo, and H. Saxen. 2000. Predominance of class II papG allele of Escherichia coli in pyelonephritis in infants with normal urinary tract anatomy. J. Infect. Dis. 181:1822-1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson, J. R. 1991. Virulence factors of Escherichia coli urinary tract infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 4:80-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson, J. R., and A. L. Stell. 2000. Extended virulence genotypes of Escherichia coli strains from patients with urosepsis in relation to phylogeny and host compromise. J. Infect. Dis. 181:261-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurazono, H., S. Yamamoto, M. Nakano, G. B. Nair, A. Terai, W. Chaicumpa, and H. Hayashi. 2000. Characterization of a putative virulence island in the chromosome of uropathogenic Escherichia coli possessing a gene encoding a uropathogenic-specific protein. Microb. Pathog. 28:183-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langermann, S., S. Palaszynski, M. Barnhart, G. Auguste, J. S. Pinkner, J. Burlein, P. Barren, S. Koening, S. leath, C. H. Jones, and S. J. Hultgren. 1997. Prevention of mucosal Escherichia coli infection by FimH-adhesin-based systemic vaccination. Science 276:607-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lipsky, B. A. 1989. Urinary tract infections in men. Epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Ann. Intern. Med. 110:138-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martínez-Martínez, L., F. Fernández, and E. Perea. 1999. Relationship between haemolysin production and resistance to fluoroquinolones among clinical isolates of Escherichia coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 43:277-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitsumori, K., A. Terai, S. Yamamoto, S. Ishitoya, and O. Yoshida. 1999. Virulence characteristicis of Escherichia coli in acute bacterial prostatitis. J. Infect. Dis. 180:1378-1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mobley, H. L. T. 2000. Virulence of the two primary uropathogens. ASM News 66:403-410. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naber, K. G. 2000. Treatment options for acute uncomplicated cystitis in adults. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 46(Suppl. S1):23-27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruiz, J., M. M. Navia, J. Vila, and J. Gascón. 2002. Prevalence of sat gene among clinical isolates of Shigella spp. causing traveler's diarrhea: geographical and specific differences. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1565-1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sussman, M., and D. L. Gally. 1999. The biology of cystitis: host and bacterial factors. Annu. Rev. Med. 50:149-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vargas, M., J. Gascón, F. Gallardo, M. T. Jiménez de Anta, and J. Vila. 1998. Prevalence of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli strains detected by PCR in patients with travelers' diarrhea. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 4:682-688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Velasco, M., J. P. Horcajada, J. Mensa, A. Moreno-Martínez, J. Vila, J. A. Martínez, J. Ruiz, M. Barranco, G. Roig, and E. Soriano. 2001. Decreased invasive capacity of quinolone resistant Escherichia coli in urinary tract infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 33:1682-1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vila, J., J. Ruiz, F. Marco, A. Barceló, P. Goñi, E. Giralt, and M. T. Jiménez de Anta. 1994. Association between double mutation in gyrA gene of ciprofloxacin-resistant clinical isolates of Escherichia coli and minimal inhibitory concentration. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:2477-2479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vila, J., K. Simon, J. Ruiz, J. P. Horcajada, M. Velasco, M. Barranco, A. Moreno, and J. Mensa. 2002. Are quinolone-resistant uropathogenic Escherichia coli less virulent? J. Infect. Dis. 186:1039-1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vila, J., M. Vargas, I. R. Henderson, J. Gascón, and J. P. Nataro. 2000. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli virulence factors in traveler's diarrhea. J. Infect. Dis. 182:1780-1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamamoto, S., A. Terai, K. Yuri, H. Kurazono, Y. Takeda, and O. Yoshida. 1995. Detection of virulence factors in Escherichia coli by multiplex polymerase chain reaction. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 12:85-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]