Abstract

A new type of swab (Cellswab; Cellomeda, Turku, Finland), utilizing a highly absorbent cellulose viscose sponge material, was compared to some traditional swabs. The survival of 14 aerobic and 10 anaerobic and microaerophilic bacterial species in the Cellswab, two commercial swab transport systems (Copan, Brescia, Italy, and Orion Diagnostica, Espoo, Finland), and one Dacron swab (Technical Service Consultants Ltd. [TSC], Heywood, United Kingdom) was evaluated. Bacteria were suspended in broth, into which the swabs were dipped. The Cellswab absorbed 1.3 times more fluid and released 3.5 times more fluid upon plating than the other swabs. Aerobic bacteria were stored in dry tubes, the others in transport medium, at 4°C and room temperature (RT), for up to 14 days. Swab samples were transferred to plates at 0, 1, 2, 4, 7, and 14 days. For 10 strains the Cellswab yielded ≥10% of the original CFU for longer than all the other swabs. In the clinical study, the ability of the Cellswab to detect beta-hemolytic streptococci from throat samples (n = 995) was compared to that of the TSC Dacron swab. The swabs performed equally, both when their samples were transferred to plates immediately and after storage for 1 day at 4°C or RT. The changes in normal microbiota after storage were also similar. The Cellswab was found to perform at least as well as ordinary swabs. It was better at storing fastidious strains, and at keeping bacteria viable for long storage times; it might well be a useful replacement or complement to ordinary swabs.

In clinical diagnostics, successful sampling and transfer of the pathogen to the laboratory is crucial: if this step fails, no amount of sophisticated and expensive laboratory procedures will enable a diagnosis, and this might lead to inadequate treatment of the patient. Swabs are a very much used type of sampling device, and the swab material plays a major, but often overlooked, role in sampling. Different swabs and transport systems have been evaluated to some extent in the past (3-6, 9, 11, 14).

The classical cotton wool tip type model is still the favorite and has remained essentially the same for at least half a century. Cotton has been found to sometimes contain inhibitory fatty acids (7); nowadays other cotton-like materials, like Dacron (polyester) or rayon (viscose), are preferred. The cotton wool type swab is, however, not necessarily an optimal design for the absorbance and release of microbes; it is relatively hard and unyielding, and bacteria might become trapped by the fibers. Swab design could be improved much by using the possibilities of modern technology.

We have developed a cellulose sponge-tipped swab, the Cellswab (Cellomeda, Turku, Finland; patent pending), using a pressure molded cellulose viscose sponge originally developed for experimental surgery and wound healing research (15). It has been shown to be an excellent matrix for tissue regrowth (10). The wet sponge has a soft and yielding texture, with a homogenous pore structure.

Here we evaluate the performance of the Cellswab: its ability to maintain the viability of representatives of 14 aerobe and 10 anaerobe and microaerophilic species under laboratory conditions, and its capacity to absorb and release fluids. The ability of the swab to preserve gonococci during mail transport was also studied. The Cellswab was compared to three commonly used commercial swabs. In addition, the abilities of the Cellswab and a standard swab to detect beta-hemolytic streptococci from patient throat samples were compared.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tested swabs.

The Cellswab (Cellomeda, Turku, Finland) is a cellulose sponge molded onto the tip of a plastic shaft; it consists of micropores with a diameter of 5 to 15 μm and macropores with a diameter of 0.4 to 0.9 mm. It swells markedly upon contact with fluid. It was compared to two commonly used swab systems—(i) the Venturi Transystem, Copan, Brescia, Italy, consisting of Dacron-tipped plastic shafts and Amies transport medium, and (ii) the Transpocult system, Orion, Espoo, Finland, consisting of Dacron-tipped wooden shafts and Stuart modified medium—and one Dacron swab without transport medium (Technical Service Consultants Ltd. [TSC], Heywood, United Kingdom).

Fluid absorption.

The swabs were weighed before and after immersion in the diluted bacterial solution, after storage, and after plating. This was done during preliminary experiments, where Dacroswab type 3 (Spektrum Laboratories, Inc.) was used instead of the TSC Dacron swab.

Viability testing.

The bacteria (Tables 1 and 2) were inoculated into brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.), grown for 2 to 3 h at 35°C, and diluted with BHI broth to a density corresponding to a 0.5 McFarland standard. From this a working dilution of usually 1:100, 1:1,000, or 1:10 (Campylobacter jejuni) was made, with the aim of obtaining countable CFU (ca. 10 to 1,000, depending on species morphology), at levels detectable for at least 24 h, as well as showing any growth occurring in the swab. Growth could be observed only if the dilution was not too dense; the experiment was repeated if necessary to achieve this. Human blood was used to make the working dilution in a set of tests with Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Streptococcus pneumoniae. The swabs were dipped for 5 s into the dilution and allowed to drain. In each separate experiment, all the different swabs were dipped into the same bacterial dilution. Separate swabs (from the same dilution) were made for each time point at which samples were to be transferred to plates. Duplicate swabs were inoculated in the experiment using blood; the 24 control species (Tables 1 and 2) were tested in triplicate at each time point.

TABLE 1.

Viability of a selection of aerobically growing species suspended in BH1 and held in swabs in dry tubesa

| Strain and temp (°C) | Cellswab

|

TSC Dacron

|

Copan

|

Orion Transpocult

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of days with ≥10% of the original no. of CFU detected | Original no. of CFU detected | No. of days with ≥10% of the original no. of CFU detected | Original no. of CFU detected | No. of days with ≥10% of the original no. of CFU detected | Original no. of CFU detected | No. of days with ≥10% of the original no. of CFU detected | Original no. of CFU detected | |

| Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 19606 | >5 × 103c | >5 × 103 | >5 × 103 | >5 × 103 | ||||

| 23 ± 1 | ≥14b | ≥14b | ≥14b | ≥14b | ||||

| 4 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6051 | 250 | 200 | 200 | 100 | ||||

| 23 ± 1 | ≥14b | ≥14b | ≥14b | ≥14b | ||||

| 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Bordetella pertussis clinical strain | >5 × 103 | >5 × 103 | >5 × 103 | >5 × 103 | ||||

| 23 ± 1 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | ||||

| 4 | ≥14 | 4 | 4 | 2 | ||||

| Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29 212 | 1 × 103 | 1 × 103 | 1 × 103 | 1 × 103 | ||||

| 23 ± 1 | ≥14b | ≥14b | ≥14b | ≥14b | ||||

| 4 | ≥14b | ≥14b | ≥14b | ≥14b | ||||

| Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 | 770 | 1 × 103 | 700 | 1 × 103 | ||||

| 23 ± 1 | ≥14b | ≥14b | ≥14b | ≥14b | ||||

| 4 | ≥14 | ≥14 | 7 | 4 | ||||

| Haemophilus influenzae ATCC 49 247 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | ||||

| 23 ± 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 13124 | 2 × 103 | 2 × 103 | 1 × 103 | 2 × 103 | ||||

| 23 ± 1 | ≥14b | ≥14b | ≥14b | 7 | ||||

| 4 | ≥14b | ≥14b | ≥14b | ≥14b | ||||

| Moraxella catarrhalis ATCC 25238 | >5 × 103 | 400 | >5 × 103 | 500 | ||||

| 23 ± 1 | ≥14b | 0 | 7b | 0 | ||||

| 4 | 7 | 2 | 4 | 2 | ||||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 | 1 × 103 | 1 × 103 | 1 × 103 | 1 × 103 | ||||

| 23 ± 1 | ≥14b | ≥14b | ≥14b | ≥14b | ||||

| 4 | ≥14 | ≥14 | ≥14 | ≥14 | ||||

| Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 | 1 × 103 | 1 × 103 | 1 × 103 | 1 × 103 | ||||

| 23 ± 1 | ≥14b | ≥14b | ≥14b | ≥14b | ||||

| 4 | ≥14 | ≥14 | ≥14 | ≥14 | ||||

| Staphylococcus epidermidis ATCC 35989 | 1 × 103 | 1 × 103 | 1 × 103 | 1 × 103 | ||||

| 23 ± 1 | ≥14b | ≥14b | ≥14b | ≥14b | ||||

| 4 | ≥14 | 7 | 7 | 7 | ||||

| Streptococcus pneumoniaed ATCC 49619 | 170 | 67 | 48 | 14 | ||||

| 23 ± 1 | 7b | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 4 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Streptococcus pyogenes ATCC 10389 | 1 × 103 | 500 | 400 | 300 | ||||

| 23 ± 1 | ≥14b | ≥14b | ≥14b | 7b | ||||

| 4 | ≥14 | ≥14 | ≥14 | ≥14 | ||||

| Yersinia enterocolitica CCUG 8233 | 1 × 103 | 1 × 103 | 1 × 103 | 1 × 103 | ||||

| 23 ± 1 | ≥14b | ≥14b | ≥14b | ≥14b | ||||

| 4 | ≥14b | ≥14b | ≥14 | ≥14b | ||||

Each swab was tested in triplicate for each time point and temperature. The swab contents were streaked onto plates after storage for 0, 1, 2, 4, 7, and 14 days. A survival of 0 days means that less than 10% of the original CFU (amount transferred from swab the same day as inoculated) grew upon being transferred to the plate at day 1.

Increase in CFU (growth in the swab) was observed.

The increase here was seen as a change from separate colonies to confluent growth.

In earlier experiments, denser inocula (>500 CFU for all swabs), but only 4 days of storage, were used; the results did not differ from those presented here.

TABLE 2.

Viability of a selection of anaerobic and microaerophilic species suspended in BHI held in swabs in transport mediuma

| Strain and temp (°C) | Cellswab + Amies

|

Cellswab + Stuart

|

Copan + Amies

|

Orion + Stuart

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of days with ≥10% of the original no. of CFU detected | Original no. of CFU detected | No. of days with ≥10% of the original no. of CFU detected | Original no. of CFU detected | No. of days with ≥10% of the original no. of CFU detected | Original no. of CFU detected | No. of days with ≥10% of the original no. of CFU detected | Original no. of CFU detected | |

| Actinomyces israelii ATCC 10049 | 18 | 44 | 15 | 17 | ||||

| 23 ± 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | ||||

| 4 | ≥14 | ≥14 | ≥14 | ≥14 | ||||

| Bacteroides vulgatus clinical strain | 300 | 500 | 150 | 200 | ||||

| 23 ± 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Campylobacter jejuni NCTC 143483 | 5 × 103 | 5 × 103 | 5 × 103 | 5 × 103 | ||||

| 23 ± 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | ||||

| Clostridium difficile ATCC 17858 | 150 | 250 | 250 | 300 | ||||

| 23 ± 1 | ≥14 | ≥14 | ≥14 | ≥14 | ||||

| 4 | ≥14b | ≥14b | ≥14 | ≥14 | ||||

| Clostridium perfringens ATCC 13124 | 30 | 50 | 16 | 5 | ||||

| 23 ± 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 4 | ≥14 | ≥14 | 7 | ≥14 | ||||

| Eubacterium lentum clinical strain | 2 × 103 | 2 × 103 | 2 × 103 | 2 × 103 | ||||

| 23 ± 1 | 7 | ≥14 | 7 | 7 | ||||

| 4 | ≥14 | ≥14 | ≥14 | ≥14 | ||||

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae ATCC 49226 | 2 × 103 | 2 × 103 | 2 × 103 | 103 | ||||

| 23 ± 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 1 | ||||

| Peptostreptococcus anaerobius clinical strain | 103 | 103 | 600 | 600 | ||||

| 23 ± 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||||

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | ||||

| Prevotella intermedia ATCC 33563 | 1.4 × 103 | 3.3 × 103 | 1.8 × 103 | 3.2 × 103 | ||||

| 23 ± 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Propionibacterium propionius ATCC 14157 | 5 × 103 | 5 × 103 | 5 × 103 | 5 × 103 | ||||

| 23 ± 1 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 1 | ||||

| 4 | ≥14 | ≥14 | ≥14 | ≥14 | ||||

See Table 1 for details.

Increase in CFU (growth in the swab) was observed.

The swabs were stored at 4°C and room temperature (RT) (incubator at 23 ± 1°C), aerobes in dry tubes to allow us to evaluate the effect of the swab material with a minimum of confounding factors, and anaerobes and microaerophiles in the transport medium supplied with the swab. When medium was used, the Cellswab was tested with the media of both commercial systems. Two versions of Copan's Amies medium were used, according to the manufacturer's recommendation: for N. gonorrhoeae and C. jejuni, Amies with charcoal was used, and for the anaerobes, Amies without charcoal was used.

The swab samples were transferred to plates immediately (to give the original CFU) and after storage. The swabs were rubbed evenly over the whole plate: 10 streaks starting from the far edge to the middle, and then the plate was rotated 90° and the process was repeated, in all four times. An attempt to standardize the pressure applied to the plates, using weighing scales, proved impractical. In practice, the pressure applied probably deviates very little from the optimal; there is a fairly narrow range between too little contact and crushing the agar. The structure of the swabs is more important: the more yielding (like the Cellswab) the swab is, the better the contact is. The plates were incubated under the conditions and for the time appropriate for each different species, after which the CFU were counted using a mechanical plate counter or estimated (CFU less than about 100 were always counted; on plates with ca. 100 to 500 CFU, at least one plateful of CFU was counted, but if the rest of the plates were perceived to contain the same amount, they were not counted; the CFU on plates with >500 colonies was usually only estimated). The CFU count after storage of the swabs was compared to the original CFU count, and the percentage of surviving colonies was calculated.

Survival of N. gonorrhoeae during mail transport.

Gonococcal strains from clinical laboratories around Finland are gathered yearly at two national reference laboratories, of which ours is one; the strains are usually sent by mail, but this is perceived as problematic. Strains are often difficult to revive upon arrival: they are usually sent both in a transport system, as well as on agar plates, which are considered the best medium, but the latter often break or spill.

In August 2000, 28 clinical gonococcal isolates and the above ATCC control strain were grown as described above in the microbiological laboratory of the Central Hospital of Vasa, 350 km north of Turku (the location of the reference laboratory). For each strain, a fairly dense working dilution was made in BHI broth: the cell densities were checked by plate counts, and were found to vary between 102 and 6 × 105 viable CFU/ml. However, this should not affect the comparison of the swabs, since the same suspension was used for all the 10 swabs inoculated with one strain. Each strain was inoculated in duplicate onto the different swab/swab-medium combinations (Table 3), packed into a parcel together with a temperature logger (Tinytag Ultra; Gemini, Chichester, United Kingdom), and posted. Two similar batches were made two days apart, so that the first batch spent 2 nights in the post, and the second 3 nights (over the weekend). Upon arrival in Turku, the swab samples were transferred to plates as described above, and the resulting CFU were counted.

TABLE 3.

Survival rate of 29 N. gonorrhoeae strains transported by mail

| Swab and transport medium | 2 days of transporta

|

3 days of transportb

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of strains growing upon arrival | Avg no. of CFU | No. of strains growing upon arrival | Avg no. of CFU | |

| Cellswab (dry tube) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Cellswab + Copan Amies medium | 24 | 131 | 12 | 43 |

| Cellswab + Orion Stuart medium | 13 | 90 | 5 | 23 |

| Copan + Amies medium | 18 | 61 | 5 | 18 |

| Orion + Stuart medium | 1 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

Median temperature, 23°C; minimum and maximum temperatures, 16 and 26°C, respectively.

Median temperature, 21°C; minimum and maximum temperatures, 16 and 23°C, respectively.

Clinical study.

Patients presenting with a suspected streptococcal throat infection at a private health center, Pulssi, in Turku, between December 2000 and September 2001, were sent to the laboratory for throat culture, and were there requested to participate in the study. Voluntary patients were given a leaflet informing about the study, and they signed a written consent form before participating. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Central Hospital District and Turku University. The new Cellswab was compared to a standard Dacron swab (TSC). Throat swabs were taken in the usual way; each patient was sampled with both swabs. The new Cellswab was used first on even dates, the Dacron swab was used first on odd dates. Fourteen different laboratory nurses did the sampling: one nurse sampled on average 70 patients (range, 18 to 152).

The patient samples were transferred at once onto sheep blood agar base plates (Oxoid Unipath Ltd., Basingstoke, United Kingdom) containing oxolinic-colistin acid supplement (plates made by Tammer-Tutkan Maljat Oy, Tampere, Finland): the swab was rolled over one-sixth of the plate, thereafter the inoculum was streaked into four quadrants, as described by Finegold and Baron (7). The swabs were then transferred into tubes containing Stuart transport medium (2) and stored for 1 day, at room temperature or 4°C, after which they were transferred to plates as described above. The plates were incubated at 35°C for 18 h. The number of beta-hemolytic colonies was counted or approximated by experienced microbiology nurses, and noted for the respective quadrant. Lancefield serological groups were determined using the Strep Plus, Streptococcus Grouping Kit (Oxoid).

The last quadrant to harbor normal flora was also noted. The numbering of the plates was randomized, so that the person reading the plate did not know which swab had been used to inoculate it.

Statistical methods.

Differences in fluid absorption were compared with the Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric test for variance, corrected for ties, and Dunn's Multiple Comparison test, using InStat (version 3.05; GraphPad Software Inc. San Diego, Calif.). The clinical data in Tables 4 to 6 were analyzed using the kappa coefficient (8), the McNemar test, and the sign test.

TABLE 4.

Positive throat samples in clinical study

| Swab and sampling order | Total (994 patients) | No. positive for beta-hemolytic streptococci |

|---|---|---|

| Cellswab firsta | 513 | 218 |

| TSC Dacron second | 513 | 220 |

| Cellswab second | 481 | 223 |

| TSC Dacron first | 481 | 212 |

Throat swabs were taken with both swabs from each patient (Cellswab first on even dates, TSC Dacron first on odd dates).

TABLE 6.

Changes in normal microbiota counts in throat swabs after storage for 1 day in Stuart medium

| Storage temp and swab | Total no. of swabs | No. of swabs (%) with indicated change

|

Kappa coefficient (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increase | Reduction | None | |||

| 4°C | |||||

| Cellswab | 626 | 123 (20) | 243 (39) | 260 (42) | 0.10 (0.04-0.16)a |

| TSC Dacron | 626 | 104 (17) | 261 (42) | 261 (42) | 0.09 (0.04-0.16)a |

| RT | |||||

| Cellswab | 358 | 105 (29) | 95 (27) | 158 (44) | 0.09 (0.01-0.17)a |

| TSC Dacron | 358 | 97 (27) | 101 (28) | 160 (45) | 0.07 (0.01-0.15)a |

Indicates poor agreement between the results before and after storage.

The kappa coefficient was used to measure the strength of agreement both between the two swabs and between the two time points within a swab. Kappa is a chance-corrected agreement index. Correction is needed because some of the agreement can occur purely by chance, and that should be taken into account. In the case of a perfect agreement the value of kappa is 1. Values greater than 0.75 were taken as an excellent agreement, values between 0.60 and 0.75 were taken as good, those between 0.40 and 0.60 were taken as fair, and values below 0.40 were taken as a poor agreement. To determine if either swab performed better, the McNemar test was used when the outcome was dichotomous, and the sign test was used when the outcome was measured on an ordinal scale. The level of significance was set equal to 0.05. The computations were carried out using SPSS/WIN Release 10 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois) and StatXact-4 software (Cytel Software Corporation, Cambridge, Mass.).

RESULTS

Fluid absorption by the swabs.

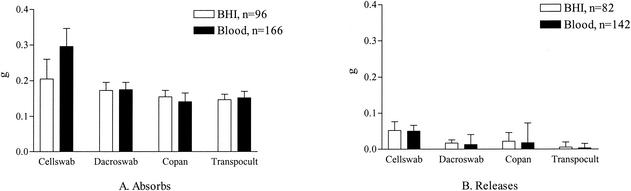

The Cellswab absorbed 205 ± 56 μg BHI broth suspension (mean ± standard deviation), which was 1.3 times more than the other swabs on average (range, 1.2 to 1.4 times) (Fig. 1A). It then released 52 ± 25 μg of this liquid upon plating: 3.5 times more than the mean amount of the other swabs (range, 2.3 to 37.5) (Fig. 1B). The higher viscosity of blood did not change this difference (black columns in Fig. 1B); in fact the Cellswab now released 4.4 times (range, 2.8 to 84.1) more fluid than the other swabs.

FIG. 1.

Fluid absorption capacity of the swabs and amount of fluid released upon sample transfer to plates.

Since the data did not follow a normal distribution, the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test had to be used for the statistics. This test does not use direct measurement data, but instead ranks the data points from the smallest to the largest, and uses this ranking as a basis for further calculations. The approximate P was <0.001 for all four swab comparisons (BHI broth absorption and release, and blood absorption and release), suggesting that there were significant differences between the swabs. Pairwise comparison of the mean ranks of absorption and release showed that all swab pairs in the four comparisons differed significantly, except BHI broth absorption for Cellswab and Dacroswab, and BHI broth and blood release for Dacroswab and Copan.

Survival of clinically important bacterial species.

Fourteen aerobically growing, and 10 microaerophilic or anaerobic species suspended in BHI broth were stored in the swabs for 14 days. The Cellswab performed better than all the other swabs with five aerobes (Bordetella pertussis, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and S. pneumoniae) (Table 1), four anaerobes (Bacteroides vulgatus, C. jejuni, Clostridium perfringens, and Eubacterium lentum), and N. gonorrhoeae (Table 2) and performed equally well, or better than just some of the other swabs, for the rest of the test organisms.

As could be expected, some species were better preserved after RT storage, while others preferred the lower temperature. Differences between the two transport media used to store anaerobes appeared when the Cellswab was stored in both; e.g., Stuart modified medium at 4°C proved to be better at preserving N. gonorrhoeae than Amies charcoal at either temperature (Table 2). In the Orion transport system, however, the good performance of the Stuart medium was more than countered by the inhibitory effect of the wooden-shafted swab (Table 3).

The starting CFU were often very similar for the different swabs dipped in the same bacterial suspension, and with a few exceptions, within each swab type the original CFU were estimated to be practically the same.

Survival of N. gonorrhoeae and S. pneumoniae suspended in blood.

To simulate wound samples with leukocytes, blood, instead of broth, was used as diluent in one experiment; the Cellswab matrix is documentedly cell-friendly (10), and could theoretically have promoted phagocytosis of the sample.

When suspended in blood and stored in dry tubes, S. pneumoniae was recovered without losses from all swabs stored at 4°C, and during RT storage they multiplied in all swabs (best in the cellulose sponge) but that of Orion Transpocult, for the 6 days tested. Over 10% of the original CFU were recovered from all swabs after 1 d storage of N. gonorrhoeae in dry tubes, at 2 days only scattered colonies were seen. A BHI broth suspension of N. gonorrhoeae in dry tubes gave results similar to the blood suspension.

Survival of N. gonorrhoeae samples in the mail.

The Cellswab, when combined with either of the two transport media, again performed better than the other swabs: after 2 days of transport, 24 of 29 were recovered from the Cellswab in Amies charcoal, compared to only 1 of 29 from the Orion Transpocult system (Table 3). The temperature in the parcels—measured with the temperature logger—had varied between 16 and 26°C. The starting concentration of each strain was determined by CFU counts of the working dilutions: despite the large variation, it did not correlate with the recovery rate. Strain differences were apparently more important than initial sample density.

Clinical study. (i) Detection of beta-hemolytic streptococci in throat samples.

Of 994 patients participating, 469 tested positive for beta-hemolytic streptococci (with at least one swab) when the swab samples were transferred to plates directly. There were no significant differences between the two swabs tested; in fact they performed nearly equally (Table 4). Of all the samples, 47.2% were positive with at least one swab; 44.4% were positive with the Cellswab, and 43.5% with the TSC Dacron swab. The McNemar test indicated that neither of the two swabs gave more positive results than the other (P = 0.264). The agreement between the swabs, calculated using the chance-correcting kappa coefficient, was 0.867 (95% CI 0.836 to 0.898), which is excellent; samples were thus usually either positive with both swabs or negative with both.

The bacterial yields were also similar; according to the sign test, there were no differences between the two swab types when CFU were compared quadrant-wise (quadrant 1, P = 0.942; 2, P = 0.089; 3, P = 0.851; 4, P = 0.178). The swabs also detected different serotypes equally. The majority of the isolates (62%; the average of positives for all groups) belonged to Lancefield group C; 17% belonged to group G, and 10% to group A.

(ii) Effects of storage on sample quality.

After the swabs had been stored for 1 day in Stuart medium, data were obtained for 983 patients. For most patients, the result did not change, but—combining the results from both swabs—11.1% of the previously positive samples became negative, and 5.5% of the negative samples gave a positive result. Still, for each swab, when comparing the results of direct plating to those after storage at 4°C or RT, using the kappa coefficient, the agreement was excellent, varying between 0.79 and 0.85.

When comparing the direction of the changes, however, the agreement, according to the kappa coefficient, seemed only fair (Table 5). Still the agreement was significant (P < 0.001). This might be due to the fact that for most of the swabs the result did not change. Neither swab did better than the other.

TABLE 5.

Beta-hemolytic streptococci detection in throat sampling: agreement of the direction of change in the result after 1 day of storage of the swabs

| Cellswab storage temp and change | No. of TSC Dacron swabs with indicated change

|

Total no. of swabs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Negative- positive | Positive- negative | ||

| 4°Cc | ||||

| Nonea | 551e | 9 | 18 | 578 |

| Negative-positive | 5 | 4 | 9 | |

| Positive-negative | 18 | 1 | 19 | 38 |

| Total | 574 | 14 | 37 | 625 |

| RTd | ||||

| None | 312 | 9 | 7 | 328 |

| Negative-positive | 4 | 8 | 12 | |

| Positive-negative | 7 | 2 | 9 | 18 |

| Total | 323 | 19 | 16 | 358 |

For the sign test (see also footnotes c and d), the changes were ranked in the order: (i) no change (best, since immediate detection is preferable), (ii) negative the first day to positive after storage, and (iii) positive to negative (worst alternative). The sign test compares the number of discrepant results (in lightface type); the nonsignificant P values (see footnotes c and d) show that neither swab performed better than the other.

The kappa coefficient of agreement between the swabs was only fair, meaning that the direction of change was fairly random, but the P values were significant (see Results).

Kappa = 0.44 (95% CI, 0.32-0.57); P < 0.001; sign test P = 0.78.

Kappa = 0.52 (95% CI, 0.37-0.67); P < 0.001; sign test P = 0.71.

Boldface type shows complete agreement between the swabs.

(iii) Normal microbiota.

When the TSC Dacron swab normal microbiota data was compared to the Cellswab results, there were no differences in the amount of normal throat microbiota collected by the two swabs (P = 0.098). When considering the sampling order, however, the swab used first turned out to collect significantly more normal flora. Cellswab used first gave more normal flora than the TSC swab in 73 cases, and the TSC swab more than Cellswab in 47 cases, P = 0.022; TSC Dacron used first gave more normal flora than the Cellswab in 100 cases, and the Cellswab more than the TSC swab in just 46 cases, P < 0.001. Most plates (48 to 59%) had normal flora growing into the third quadrant; just 1 to 2% had normal flora only in the first quadrant.

The changes in the amount of normal microbiota after storage were substantial. Increase as well as reduction was seen at both temperatures (Table 6). However, there were no differences in the performance of the swabs (P = 1.00 at 4°C; P = 0.861 at RT).

DISCUSSION

The new cellulose sponge swab was found to perform at least as well as the traditional swabs, and often it performed better. The ability of the sponge to absorb and release larger amounts of liquid than the other swabs is one reason; another reason is the cell-friendly environment of the swab.

This is not the first use of sponges in microbiological sampling and transport: Becton Dickinson has a polyurethane sponge swab, the Culturette EZ, which according to one study appeared hydrophobic, and absorbed only 28 μl during a 5-s immersion, which affected bacterial yields negatively (12). Another study found that despite a much greater initial yield (after a 30-second immersion) from this polyurethane sponge than from ordinary swabs, the viability of N. gonorrhoeae over 24 h was very poor (1). The Cellswab absorbed nearly 10 times more than reported for the Culturette EZ swab in 5 s and generally had a positive effect on viability compared to the control swabs.

Copan and Starplex Scientific have transport systems with liquid medium, held by a sponge, instead of agar at the bottom of the tube. Starplex used a cellulose sponge, which was found to contain inhibitory substances (13). The possible inhibitory substances in cellulose sponges are remains from the manufacturing process: sulfur compounds used to break down the wood fibers, or chlorine residues from bleaching. They can be removed by thorough washing, to give a highly pure end product. Clearly, the Cellswab does not contain inhibitors, since many strains were able to grow in the sponge, and even fastidious strains fared no worse, if not better, than in the other swabs. However, growth in the swab was, with the exception of C. difficile, seen only in the experiments where samples were stored in BHI broth-drenched swabs in dry tubes, without the benefit of a growth-inhibiting medium; this was thus not unexpected. It was not due to nutrients released from the sponge material: S. pyogenes suspended in physiological saline died within 24 h at RT (preliminary data). This growth, however, suggested that normal microbiota overgrowth in samples from nonsterile sites could be a potential problem; this had to be addressed in a clinical setting.

In the survival study (Tables 1 and 2), a follow-up time of 14 days was chosen, to get a general idea of the performance of the new swab material in comparison to the old ones. Delays in specimen processing in a clinical setting would not be expected to be more than a couple of days: therefore an overnight storage was chosen for the clinical samples. The absence of any clear benefit of the new sponge swab in the detection of beta-hemolytic streptococci from patient samples was no surprise in the light of the above results from the laboratory studies: S. pyogenes survived well for at least 14 days at 4°C in all swabs. Overall, the new swab material was most advantageous for fastidious organisms, or for storage longer than 1 day. The new swab might have made a bigger difference in a clinical study aimed to detect gonococci or pneumococci. To set up a clinical study to collect such samples would, however, have been difficult, if not impossible. Pneumococci would have had to be collected from middle ear effusions; equal, clinically acceptable sampling of such material with two swabs is difficult, because of the small amount of pus available. There were only 271 gonorrhea cases in Finland in the year 2000, according to the Finnish Infectious Diseases Register at the National Public Health Institute (http://www.ktl.fi/ttr/, in Finnish); it would have taken many years to reach a sufficient sample size, even if all the larger laboratories in the country had agreed to participate in such a study.

It was interesting to see that storage in Stuart transport medium for 1 day did not have much impact on the number of positive samples. On an individual sample level, the swabs agreed over the result (changed or not) in 92% of the cases (Table 5), which gave a kappa factor of only fair, but significant agreement. This seems to be mainly caused by chance: neither the sample in itself nor the swab can be the main factors causing the discrepancy, since none of the swabs fared worse.

The similarity of the changes in normal flora recovery from the two swabs after storage was a positive surprise, in view of the above laboratory experiments showing growth in the swab. Normal flora overgrowth was no bigger problem with the Cellswab than with the TSC swab. The Cellswab, even if it was no better at detecting the relatively undemanding beta-hemolytic streptococci, can thus be expected to be at least equal to an ordinary swab in all respects. It could be particularly useful when the processing of samples containing fastidious strains is delayed, or for long transports. The documented ability of the sponge to preserve human cells (10, 15) could be useful for sample types that have to contain whole cells, e.g., for virological testing.

In conclusion, through its superior fluid-releasing properties and good viability-preserving properties, the Cellswab proved to be a competitive alternative to the traditional swabs, and it could be a means of improving the quality of clinical microbiology sampling.

Acknowledgments

We thank Marja-Liisa Lindman for technical assistance, the clinical microbiology laboratory at Vasa Central Hospital for providing laboratory space, and Kirsti Tuomela for providing bacterial strains. We thank Maj-Rita Siro, Eva Lindberg, and the rest of the laboratory personnel at Pulssi for taking good care of the patients and for specimen collection and handling.

Funding was provided by grant 40241/00 from TEKES (the National Technology Agency).

REFERENCES

- 1.Arbique, J., K. Forward, and J. LeBlanc. 2000. Evaluation of four commercial transport media for the survival of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 36:163-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balows, A., W. J. Hausler Jr., K. L. Herrmann, H. D. Isenberg, and H. J. Shadomy. 1991. Manual of clinical microbiology, 5th ed. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 3.Barber, S., P. J. Lawson, and D. I. Grove. 1998. Evaluation of bacteriological transport swabs. Pathology 30:179-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brook, I. 1987. Comparison of two transport systems for recovery of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria from abscesses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 25:2020-2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Citron, D. M., Y. A. Warren, M. K. Hudspeth, and E. J. C. Goldstein. 2000. Survival of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria in purulent clinical specimens maintained in the Copan Venturi Transystem and Becton Dickinson Port-A-Cul transport systems. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:892-894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farhat, S. E., M. Thibault, and R. Devlin. 2001. Efficacy of a swab transport system in maintaining viability of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2958-2960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finegold, S. M., and E. J. Baron. 1986. Bailey and Scott's diagnostic microbiology, 7th ed. The C. V. Mosby Company, St. Louis, Mo.

- 8.Fleiss, J. 1981. The measurement of interrater agreement, p. 212-236. In J. Fleiss (ed.), Statistical methods for rates and proportions. Wiley, New York, N.Y.

- 9.Hindiyeh, M., V. Acevedo, and K. C. Carroll. 2001. Comparison of three transport systems (Starplex StarSwab II, the new Copan Vi-Pak Amies agar gel collection and transport swabs, and BBL Port-A-Cul) for maintenance of anaerobic and fastidious aerobic organisms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:377-380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Märtson, M., J. Viljanto, P. Laippala, and P. Saukko. 1998. Connective tissue formation in subcutaneous cellulose sponge implants in the rat. The effect of the size and cellulose content of the implant. Eur. Surg. Res. 30:419-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olsen, C. C., J. R. Schwebke, W. H. J. Benjamin, A. Beverly, and K. B. Waites. 1999. Comparison of direct inoculation and Copan transport systems for isolation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae from endocervical specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3583-3585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perry, J. 1997. Assessment of swab transport systems for aerobic and anaerobic organism recovery. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:1269-1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perry, J., and D. Ballou. 1997. Inhibitory properties of a swab transport device. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:3367-3368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roelofsen, E., M. van Leeuwen, G. J. Meijer-Severs, M. H. F. Wilkinson, and J. E. Degener. 1999. Evaluation of the effects of storage in two different swab fabrics and under three different transport conditions on recovery of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3041-3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Viljanto, J. 1969. A sponge implantation method for testing connective tissue regeneration in surgical patients. Acta Chir. Scand. 135:297-300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]