Abstract

The present study compared the antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) results generated by the Automated Incubation and Reading System (ARIS) with custom Sensititre plates (TREK Diagnostic Systems, Cleveland, Ohio) and MicroScan PC10 GP and NUMIC10 GN plates interpreted with the WalkAway-96 system (Dade Behring, West Sacramento, Calif.) for gram-positive (GP) and gram-negative (GN) organisms as part of an in-house validation. A total of 326 isolates (3,689 antimicrobial agent-organism combinations) were evaluated. Sensititre plates were inoculated according to the instructions of the manufacturer with a suspension adjusted to a 0.5 McFarland standard, while the Prompt Inoculation System was used for the MicroScan plates. ARIS and the WalkAway system were used for automated reading of the Sensititre and MicroScan plates, respectively, at 18 to 24 h. The results were analyzed for essential (±1 twofold dilution) and categorical (sensitive, intermediate, or resistant) agreements. Plates that resulted in ARIS interpretations with major (falsely resistant) or very major (falsely susceptible) errors compared to the results obtained with the WalkAway system were read manually to corroborate instrument readings. Isolates for which very major or major errors were obtained and for which the results were not resolved by manual reading were retested in parallel. Isolates for which very major or major errors were obtained and for which the results were not resolved upon repeat testing were tested by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards M7-A5 frozen reference microdilution method. Essential agreement was 95.8% for 246 GN isolates. The following categorical error rates were obtained for the GN isolates: 1.3% minor errors, 0% major errors, and 0.4% very major errors. For 95 GP isolates, there was 93.5% essential agreement. Categorical error rates for GP isolates were 0.9% minor errors, 0.6% major errors, and 0.4% very major errors. ARIS-Sensititre is a diagnostic system feasible for use for automated AST in a clinical laboratory.

Sensititre broth microdilution antimicrobial susceptibility plates (TREK Diagnostic Systems, Cleveland, Ohio) were introduced in 1980 (4, 7); and 18- to 24-h susceptibility results have been shown to compare favorably to standardized broth microdilution (4, 5, 6, 7, 16), agar dilution (3, 13, 14, 16), and disk diffusion (5, 6, 12, 16) susceptibility results. Favorable results have also been documented with manually and semiautomatically interpreted Sensititre plates in parallel with MicroScan plates (6) with the WalkAway-96 system (Dade Behring, West Sacramento, Calif.) and the Vitek system (bioMerieux, Durham, N.C.) (6) with the Vitek automated instrument (5, 16) compared to the results of the disk diffusion and broth microdilution methods. While manually interpreted Sensititre plates are commonly used in the veterinary, surveillance, research, and pharmaceutical industries, the plates have not been commonly used in the clinical diagnostic laboratory. The antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) results generated with the fully automated Automated Incubation and Reading System (ARIS) instrument have never been directly validated in comparison with the results obtained with other commonly used automated susceptibility systems, although the results for Sensititre plates read by instruments have been compared to the results for the same plates read manually (15). The attributes of ARIS-Sensititre plates (ARIS-Sensititre), specifically, the use of a standardized inoculum, an extensive antimicrobial menu approved by the Food and Drug Administration, the availability of small lot sizes of custom susceptibility plates, no reagent addition, and minimal biohazardous waste creation, make the system worthy of evaluation for use in the clinical laboratory.

In this era of increasing antimicrobial resistance, a comprehensive comparison of ARIS-Sensititre to other widely accepted systems is apropos. The prospective, controlled study described here compared automated reading of susceptibility plates with ARIS-Sensititre and the WalkAway system-MicroScan plates (WalkAway-MicroScan) and was conducted as part of an in-house validation of the ARIS-Sensititre automated AST system in the clinical microbiology laboratory of a 250-bed, suburban teaching hospital.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Specimens.

A total of 326 isolates, consisting of freshly isolated clinical isolates (74%) supplemented with frozen clinical isolates (26%) in order to increase species diversity, were tested (Table 1). No duplicate isolates were tested. Testing was performed with both systems concurrently and occurred on 32 days between 9 April 2001 and 11 July 2001. The antimicrobials and the dilutions tested are shown in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

Isolates tested

| Organism | No. tested |

|---|---|

| Gram-negative isolates | |

| Klebsiella spp. | 42 |

| Escherichia coli | 40 |

| Proteus spp. | 32 |

| Pseudomonas spp. | 28 |

| Enterobacter spp. | 27 |

| Citrobacter spp. | 16 |

| Serratia marsescens | 12 |

| Acinetobacter spp. | 7 |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 6 |

| Miscellaneous gram-negative bacillia | 21 |

| Subtotal | 231 |

| Gram-positive isolates | |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 28 |

| Staphylococcus aureus (methicillin resistant) | 24 |

| Staphylococcus aureus (methicillin susceptible) | 12 |

| Coagulase-negative staphylococci | 11 |

| Enterococcus faecium (vancomycin susceptible) | 10 |

| Enterococcus faecium (vancomycin resistant) | 10 |

| Subtotal | 95 |

| Total | 326 |

Includes Providencia spp. (n = 9), Morganella spp. (n = 7), Flavobacterium spp. (n = 3), and Ochrobactrum anthropi (n = 2).

TABLE 2.

Antimicrobials and ranges evaluated

| Organism specificity of plates and antimicrobial | Concn (μg/ml) range

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Sensititrea | MicroScanb | |

| Gram-negative isolates | ||

| Amikacin | 0.5-32 | 2, 8-32 |

| Ampicillin | 1-16 | 1-16 |

| Ampicillin-sulbactam | 1/0.5-16/8 | 8/4-16/8 |

| Aztreonam | 8-16 | 8-16 |

| Cefazolin | 0.5-16 | 2-16 |

| Cefepime | 1-16 | 2-16 |

| Ceftazidime | 0.25-16 | 2-16 |

| Ceftriaxone | 4-32 | 4-32 |

| Gentamicin | 0.25-8 | 1-8 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.5-4 | 2-4 |

| Nitrofurantoin | 32-64 | 32-64 |

| Piperacillin | 8-64 | 8-64 |

| Tetracycline | 4-8 | 4-8 |

| Tobramycin | 4-8 | 1-8 |

| Gram-positive isolates | ||

| Ampicillin | 0.25-16 | 0.26-8 |

| Cefazolin | 2-16 | 2-16 |

| Clindamycin | 0.03-2 | 0.25-2 |

| Erythromycin | 0.12-4 | 0.25-4 |

| Gentamicin | 4-8 | 1-8 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.03-4 | 2-4 |

| Nitrofurantoin | 2-64 | 32-64 |

| Oxacillin | 0.12-4 | 0.5-4 |

| Tetracycline | 1-8 | 2-8 |

| Vancomycin | 0.5-16 | 2-16 |

CMC1ALAF (custom) plates were used for gram-negative organisms, and CMC2BLAF (custom) plates were used for gram-positive organisms.

NUM1C10 plates were used for gram-negative organisms, and PC10 plates were used for gram-negative organisms.

Quality control.

The reproducibilities of both systems were tested with 10 isolates in triplicate on 3 days. Quality control testing, which included three strains each on the plates for gram-positive and gram-negative organisms, according to guidelines M7-A5 (10) and M100-S12 (11) of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS), was performed on both ARIS and the WalkAway system on each day of testing to ensure the accuracies of the susceptibility testing results. Colony counts were performed daily for each quality control organism to ensure that a proper final inoculum density was achieved according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Furthermore, the precisions of the inoculum densities of both systems were assessed by performing colony counts for 50 consecutive Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922) inocula. The inocula for ARIS were prepared by using a 0.5 McFarland standard and standardizing the inoculum in the Sensititre nephelometer, while the Prompt Inoculation System-D was used for the WalkAway system. Colony counting was performed by transferring a 1-μl aliquot of the final inoculum into 50 and 200 μl of demineralized water with a calibrated loop. This suspension was mixed, and 1 μl was plated onto Trypticase soy agar plates with 5% sheep blood. After overnight incubation at 35°C, the colonies were counted to calculate the original inoculum density. Purity checks were performed for each inoculum for both the Sensititre and the MicroScan plates to ensure that only one organism was present.

ARIS-specific quality control.

The reproducibilities of the ARIS interpretations were assessed by performing a second automated reading of 30 plates immediately following the initial reading. The two readings were compared to determine whether the plates were being read consistently. Furthermore, the time that had elapsed between plate loading and reading was measured for 54 plates to assess the reliability of the instrument in reading the plates 18 h after they were loaded.

WalkAway system setup.

The Prompt Inoculation System-D was used to prepare inocula from several well-isolated colonies. As instructed by the package insert, three colonies were touched with the Prompt system wand, and the wand was subsequently placed into 30 ml of Prompt system diluent and the contents were mixed. Dried plates (PC10 and NUMIC10 plates for gram-positive and gram-negative organisms, respectively) were dosed with a RENOK handheld inoculator. The plates were read at 18 to 24 h by the WalkAway system linked to a computer with Data Management System software (version 22.28).

ARIS setup.

Several isolated colonies were used to prepare a suspension equivalent to a 0.5 McFarland standard by using the Sensititre nephelometer. A disposable 10-μl calibrated loop was used to aseptically transfer the suspension into 10 ml of Sensititre cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth. Custom-formatted Sensititre plates (CMC2BLAF and CMC1ALAF plates for gram-positive and gram-negative organisms, respectively) were inoculated by using the AutoInoculator, an automated robotics-driven dosing platform that delivers 50 μl of broth to each well. The plates were read at 18 to 24 h by ARIS linked to a computer running Sensititre Automated Microbiology System software (version 2.4).

Data analysis.

Susceptibility results were analyzed for essential (within ±1 twofold dilution) and categorical (sensitive, intermediate, or resistant) agreement according to NCCLS guidelines. The results obtained with ARIS (the test system) were compared to those obtained with the WalkAway system (the in-house system). Only antimicrobial-organism combinations suggested by NCCLS as appropriate for routine use and reporting were evaluated (11). Essential agreement was defined as an MIC within ±1 twofold dilution with both systems. Categorical errors were classified as one of three types: minor (an intermediate versus a susceptible or resistant result), major (ARIS, resistant result; WalkAway system, susceptible result [falsely resistant]), or very major (ARIS, susceptible result; WalkAway system, resistant result [falsely susceptible]). Minor errors that were within essential agreement (plus or minus one well) were not tallied as errors. Therefore, if an MIC of 8 μg/ml, equaling a sensitive interpretation, was obtained with one system and an MIC of 16 μg/ml, equaling an intermediate interpretation, was obtained with the other system, the results were considered within essential agreement and no error was tallied. This study did not look at discrete (as opposed to off-scale [less than the lowest concentration or more than the highest concentration]) MICs because the MICs for isolates encountered in routine testing at this facility are discrete relatively rarely; however, further investigation of this system with a challenge set of organisms for which MICs are capable of being discrete is warranted.

An independent-samples t test was used to compare MicroScan and Sensititre plate inoculum densities. The mean inoculum density for each system was compared to the NCCLS range by a one-sample t test. All statistical analyses were performed with the standard version of SPSS for Windows (release 9.0.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Ill.).

Discrepant results.

Plates yielding major or very major errors were read manually by using the touchSCAN-SR (MicroScan) or the SensiTouch (Sensititre) system to corroborate the instrument readings. If major or very major errors were not resolved, the isolate was retested with both systems. The results were reevaluated, and any major or very major errors that did not resolve were arbitrated by the NCCLS M7-A5 frozen reference microdilution method (TREK Diagnostic Systems). Discrepancy analysis was performed by Lab Services at TREK Diagnostic Systems, and the previous susceptibility testing results were unknown to the individuals performing the testing. Following discrepancy analysis, all results were recalculated for major and very major error rates by using as the denominator the total number of antimicrobial-organism combinations susceptible with the WalkAway system and resistant with the WalkAway system, respectively, while minor error rates used the total number of antimicrobial-organism combinations as the denominator.

RESULTS

For the 30 isolates (589 antimicrobial-organism combinations) used to test the reproducibility of ARIS-specific automated reading, exact agreement was 97.1%, while no result varied by more than one well, thus indicating 100% essential agreement. In an evaluation of 54 plates, ARIS demonstrated reliability in performing plate reading, as all plates were read within 35 min, 18 h after they were loaded. The instrument takes approximately 1 min to read each plate; therefore, the 35-min delay in the reading of the plates is expected due to the loading of numerous plates at the same time. Quality control results for each antimicrobial-organism combination were not out of range for more than 1 day of testing. Subsequent to the implementation of Sensititre plate use, a weekly quality control testing cycle was adopted, according to NCCLS standards. In 1 year, quality control failures prompted the use of a 5-day quality control testing cycle on two occasions.

For 231 gram-negative isolates (3,111 antimicrobial-organism combinations), essential agreement was 95.8% between ARIS and the WalkAway system. Following discrepancy analysis, ARIS yielded the following categorical errors: 41 (1.3%) minor errors, 0 (0%) major errors, and 3 (0.4%) very major errors (Table 3). For 95 gram-positive isolates (758 antimicrobial-organism combinations), essential agreement was 93.5%. Following discrepancy analysis, ARIS yielded the following categorical errors: 7 (0.9%) minor errors, 3 (0.6%) major errors, and 1 (0.4%) very major error (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Performance of Sensititre compared to MicroScan after discrepancy analysisa

| Organism | No. of isolates tested | % Essential agreementb | Error rate (%)c

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minor | Major | Very major | |||

| Gram negative | 231 | 95.8 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.4 |

| Gram positive | 95 | 93.5 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.4 |

NCCLS M7 standard broth microdilution method.

Results ±1 twofold dilution.

Minor error, intermediate versus sensitive or resistant result; major error, resistant with the Sensititre system and sensitive with the MicroScan system; very major error, sensitive with the Sensititre system and resistant with the MicroScan system.

The results of discrepancy analysis for antimicrobial-organism combinations arbitrated by the NCCLS M7-A5 frozen reference microdilution method are detailed in Table 4. Individual antimicrobial-organism combinations that resulted in persistent errors after discrepancy analysis are described in Table 4 for ARIS and the WalkAway system. For ARIS, very major errors were obtained for one Providencia sp. with cefazolin and for one E. coli strain and one Klebsiella pneumoniae strain with piperacillin. Three Enterococcus spp. yielded major errors with tetracycline, while one coagulase-negative staphylococcus had a very major error with oxacillin.

TABLE 4.

Discrepancy analysis performed for isolates with major and very major errors after retesting with NCCLS M7-A5 standard reference panelsa

| Antimicrobial | Organism | MIC (μg/ml)

|

Resulting errorb

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensititre | MicroScan | Referencec | Sensititre | MicroScan | ||

| Ampicillin | Providencia sp. | 8 | >16 | 4 | Major | |

| Amp/sulbd | Klebsiella oxytoca | 8 | >16 | 16 | ||

| Cefepime | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | <1 | >16 | 1 | Major | |

| Cefazolin | Staphylococcus aureus | >16 | <2 | 32 | Very major | |

| Coagulase-negative staphylococci | <2 | >8 | 2 | Major | ||

| Klebsiella oxytoca | 8 | >16 | 16 | |||

| Providencia sp. | 1 | >16 | 8 | Very major | Major | |

| Enterobacter aerogenes | 4 | >16 | 4 | Major | ||

| Erythromycin | Staphylococcus aureus | >4 | <0.25 | >16 | Very major | |

| Nitrofurantoin | Providencia sp. | <32 | >64 | 32 | Major | |

| Oxacillin | Coagulase-negative staphylococci | 2 | >4 | >8 | Very major | |

| Piperacillin | Escherichia coli | <8 | >64 | 64 | Very major | |

| Flavobacterium sp. | 16 | >64 | 16 | Major | ||

| Flavobacterium sp. | 16 | >64 | 16 | Major | ||

| Klebsiella oxytoca | <8 | 64 | 8 | Major | ||

| Klebsiella oxytoca | <8 | >64 | 8 | Major | ||

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 16 | >64 | 64 | Very major | ||

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | <8 | 32 | 16 | |||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | >64 | 16 | 64 | Very major | ||

| Tetracycline | Enterococcus faecalis | >8 | <2 | <1 | Major | |

| Enterococcus faecium | >8 | <2 | <1 | Major | ||

| Enterococcus sp. | >8 | <2 | <1 | Major | ||

Major errors were a result of false resistance and very major errors were a result of false susceptiblity.

Reference testing favored the Sensititre system 12 times, the MicroScan system 6 times, both systems 3 times, and neither system 1 time.

NCCLS M7-A5 broth microdilution method.

Amp/sulb, ampicillin-sulbactam.

The results of discrepancy testing for 22 isolates with persistent major or very major errors exclusively favored ARIS 12 times and the WalkAway system 6 times. The results obtained with both systems agreed with those of the reference method for three isolates, while the results obtained with both systems failed to agree with those of the reference method for one isolate. The isolate was a Providencia sp. for which the MIC by the reference method was 8 μg/ml, the MIC with the WalkAway system was >16 μg/ml, and the MIC with ARIS was 1 μg/ml. For 10 of 13 isolates for which the results obtained with the WalkAway system did not agree with those obtained by the reference method, the MICs obtained with the WalkAway system were two or more wells higher than those obtained by the reference method (Table 3).

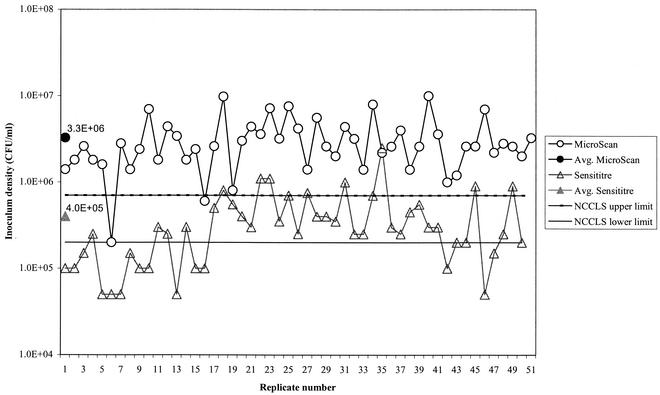

The acceptable range for the final inoculum density according to NCCLS guidelines outlined for the M7-A5 method (10) is 3 × 105 to 7 × 105 CFU/ml. Final inoculum densities, as calculated from the colony counts for 50 consecutive inocula of E. coli ATCC 25922, showed a mean inoculum density of 4.0 × 105 CFU/ml for the Sensititre system and a mean inoculum density of 3.3 × 106 CFU/ml for the MicroScan Prompt system (Fig. 1). The mean inoculum density for the MicroScan Prompt system was significantly higher (P < 0.0001) than that for the Sensititre system. The MicroScan Prompt system yielded colony counts higher than the NCCLS range for 48 of 50 replicates. While the mean colony count for ARIS was within the NCCLS range, 23 of 50 replicates yielded colony counts outside the NCCLS range (15 below the range and 8 above the range). The MicroScan Prompt system yielded a mean inoculum density significantly higher (P < 0.0001) than the NCCLS range, while the Sensititre system yielded a mean inoculum density that did not vary significantly (P = 0.392) from the NCCLS range.

FIG. 1.

Inoculum densities for Sensititre and MicroScan plates.

DISCUSSION

The ability of ARIS to provide automated susceptibility interpretations with Sensititre plates was essentially equivalent to that of the WalkAway system with MicroScan plates. After discrepancy analysis, ARIS-Sensititre demonstrated 95.8% essential agreement with WalkAway-MicroScan for gram-negative organisms and 93.5% essential agreement for gram-positive organisms. Categorical error rates for gram-negative organisms were 1.3% minor errors, 0% major errors, and 0.4% very major errors, while categorical error rates for gram-positive organisms were 0.9% minor errors, 0.6% major errors, and 0.4% very major errors. NCCLS has not set performance standards for comparisons of in vitro automated AST systems. The following guidelines have been suggested (8): overall essential agreement must be >90%, the very major error rate must be ≤3% (given that ≥35 antimicrobial-resistant organism combinations were evaluated), and the rate for the combination of minor and major errors must not exceed 7%. ARIS-Sensititre met each criterion.

The errors obtained with ARIS and the WalkAway system following discrepancy analysis were generally varied, with no major consistent problems with the antimicrobial-organism combinations tested except in three instances. For ARIS-Sensititre, false resistance to tetracycline involving three Enterococcus spp. represented 6% of susceptible results. The manufacturer has since modified one of the parameters in the algorithm for the reading of tetracycline susceptibility, but this does not affect the algorithms for the reading of susceptibilities to any of the other antimicrobials in the system. The in-house data from the manufacturer (R. Grist, TREK Diagnostic Systems, personal communication) for 105 Enterococcus isolates shows that this change eliminated false resistance errors. Problem antimicrobial-organism combinations for the WalkAway system included cefazolin with both gram-positive and gram-negative isolates and piperacillin with gram-negative isolates. With cefazolin, these were three major errors (one gram-positive isolate and two gram-negative isolates) and one very major error (a gram-positive isolate). Piperacillin yielded four major errors and one very major error with different gram-negative species.

The results of discrepancy testing exclusively favored ARIS 2:1 over the WalkAway system. In these cases, previous major or very major errors with ARIS were either resolved or changed from major to minor errors. These results suggest that the results obtained with Sensititre plates may possibly be more accurate since an increased correlation with the results of the NCCLS reference method occurs. One explanation for the difference in the agreement between the MICs obtained with the two systems and the MIC obtained by the reference method is the different methods of inoculum preparation, since some antimicrobial-organism combinations have been shown to yield false resistance if the final inoculum density is higher than recommended (2). The WalkAway system with MicroScan plates and the Prompt inoculation system yielded a mean inoculum density of 3.3 × 106 CFU/ml. This phenomenon has been described previously (9) with mean Prompt system inoculum densities of >105 CFU/ml and some antimicrobial-organism combinations, resulting in <95% essential agreement with reference MICs. While it has been suggested that inoculum density can vary over 1 log10 range without affecting most MIC results (1), further investigation into this area is warranted, given the consistency of the results in this study.

Automated AST systems vary in their performance parameters and mechanics. Evaluation of a system that has not been described previously allowed a reevaluation of the automated system used in our laboratory, the WalkAway system with MicroScan plates. The attributes of WalkAway-MicroScan include setup with the Prompt inoculation system and the RENOK inoculator, which require minimal technician time and bench space. Combination identification and susceptibility testing plates can limit testing to one plate. The chromogenic substrates and turbidity used for identification and susceptibility testing, respectively, allow the plates to be interpreted manually. The instrument has two options for plate capacity; that is, it can use either 40- or 96-plate units. In addition, the instrument offers Windows-based software that streamlines the use of WalkAway-MicroScan. The deficiencies of WalkAway-MicroScan to be considered include daily monitoring and replenishment of colorimetric substrates for identification plates, and the addition of water is necessary to maintain moisture levels. The Prompt system yields colony counts higher than the range recommended by the NCCLS. The seed trays used with the RENOK inoculator are prone to leakage, and the RENOK inoculator can inoculate only one organism per plate. The MicroScan system does not offer custom-formatted plates, and fewer Food and Drug Administration-approved antimicrobials are available on the plates for patient isolate testing. Compared to ARIS, the WalkAway system generates chemical waste and 62% more biohazardous waste (157 g/test for the WalkAway system versus 97 g/test for ARIS).

The attributes of ARIS-Sensititre include the initial standardization of the inoculation broth, as recommended by the NCCLS, and the use of a closed system for inoculation, which minimizes aerosols and the chance for contamination. ARIS requires only yearly calibration. Sensititre offers the largest selection of Food and Drug Administration-approved antimicrobials for AST plates and custom plates in lot sizes as small as 500, which allow frequent changes and testing of the antimicrobials that actually exist in individual hospital formularies. Deficiencies to consider include the use of the Sensititre inoculator, which is instrument based and which requires more time and bench space than the RENOK inoculator. Identification results cannot be interpreted manually. ARIS is available only with a 64-plate capacity. Windows-based software was still in development at the time of submission of this report and is critical for improved laboratory work flow.

Both ARIS-Sensititre and WalkAway-MicroScan performed adequately in supplying AST results. Subsequent to this comparison, ARIS-Sensititre was placed in the clinical laboratory. The substantial issues involved in making this decision were the fact that ARIS-Sensititre susceptibility results agreed with the results of the reference test more frequently than the results of WalkAway-MicroScan did for those isolates subjected to discrepancy testing, the fact that ARIS-Sensititre is able to alter the antimicrobials on susceptibility plates frequently to match the agents in the hospital formulary, and the fact that ARIS-Sensititre generates fewer chemical and biohazardous wastes. Upgraded software, which is in development, is required for the system to be compatible with high-volume use and work flow in the clinical laboratory. Once the upgraded software is available, ARIS-Sensititre will provide a necessary option for automated AST in the clinical laboratory.

Acknowledgments

We thank Scott Killian, Nikki Holliday, and Tim Kelley of TREK Diagnostic Systems Lab Services for performing discrepancy testing. We are indebted to Cindy Knapp for technical contributions and Chris Schoonmaker for performing statistical analysis.

This study was supported in part by TREK Diagnostic Systems and was also funded by the Robert E. Wise, MD, Research and Education Institute, Lahey Clinic.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barry, A. L., R. E. Badal, and R. W. Hawkinson. 1983. Influence of inoculum growth phase on microdilution susceptibility tests. J. Clin. Microbiol. 18:645-651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doern, G. V., A. B. Brueggemann, R. Perla, J. Daly, D. Halkias, R. N. Jones, and M. A. Saubolle. 1997. Multicenter laboratory evaluation of the bioMerieux Vitek antimicrobial susceptibility testing system with 11 antimicrobial agents versus members of the family Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2115-2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dowzicky, M. J., H. L. Nadler, and W. Sheikh. 1994. Comparison of Sensititre broth microdilution and agar dilution susceptibility testing techniques for meropenem to determine accuracy, reproducibility, and predictive values. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:2204-2207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gavan, T. L., R. N. Jones, and A. L. Barry. 1980. Evaluation of the Sensititre system for quantitative antimicrobial drug susceptibility testing: a collaborative study. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 17:464-469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hansen, S. L., and P. K. Freedy. 1983. Concurrent comparability of automated systems and commercially prepared microdilution trays for susceptibility testing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 17:878-886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hansen, S. L., and P. K. Freedy. 1984. Variation in the abilities of automated, commercial, and reference methods to detect methicillin-resistant (heteroresistant) Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 20:494-499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones, R. N., T. L. Gavan, and A. L. Barry. 1980. Evaluation of the Sensititre microdilution antibiotic susceptibility system against recent clinical isolates: three-laboratory collaborative study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 11:426-429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jorgensen, J. H. 1993. Selection criteria for an antimicrobial susceptibility testing system. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:2841-2844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lund, M. E., and R. W. Hawkinson. 1983. Evaluation of the Prompt Inoculation System for preparation of standardized bacterial inocula. J. Clin. Microbiol. 18:84-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1997. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility test for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard M7-A4. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 11.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2002. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 12th informational supplement. M100-S12. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 12.Nolte, F. S., K. K. Krisher, L. A. Beltran, N. P. Christianson, and G. E. Sheridan. 1988. Rapid and overnight microdilution antibiotic susceptibility testing with the Sensititre breakpoint Autoreader system. J. Clin. Microbiol. 26:1079-1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reeves, D. S., A. Holt, M. J. Bywater, R. Wise, M. N. Logan, J. M. Andrews, and J. M. Broughall. 1980. Comparison of Sensititre dried microdilution trays with a standard agar method for determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations of antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 18:844-852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Staneck, J. L. 1986. Imipenem susceptibility testing with a commercially prepared dry-format microdilution tray. J. Clin. Microbiol. 23:1134-1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Staneck, J. L., S. D. Allen, E. E. Harris, and R. C. Tilton. 1985. Automated reading of MIC microdilution trays containing fluorogenic enzyme substrates with the Sensititre Autoreader. J. Clin. Microbiol. 22:187-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Staneck, J. L., S. Glenn, J. R. DiPersio, and P. A. Leist. 1989. Wide variability in Pseudomonas aeruginosa aminoglycoside results among seven susceptibility testing procedures. J. Clin. Microbiol. 27:2277-2285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]