Abstract

Twenty-two Vibrio cholerae isolates, including some from “epidemic” (O1 and O139) and “nonepidemic” serogroups, were characterized by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and multilocus sequence typing (MLST) by using three housekeeping genes, gyrB, pgm, and recA; sequence data were also obtained for the virulence-associated genes tcpA, ctxA, and ctxB. Even with the small number of loci used, MLST had better discriminatory ability than did PFGE. On MLST analysis, there was clear clustering of epidemic serogroups; much greater diversity was seen among tcpA- and ctxAB-positive V. cholerae strains from other, nonepidemic serogroups, with a number of tcpA and ctxAB alleles identified.

Vibrio cholerae is an environmental species that has been linked with seven pandemics of cholera since 1817 (22). Approximately 200 serogroups of V. cholerae have been identified to date, with classification based on epitopic variations in the heat-stable somatic O antigens of the strains (29). In the modern microbiology era, epidemic cholera has been associated with a limited number of closely related strains in O groups 1 and 139. All such epidemic strains carry genes for cholera toxin (encoded by the ctxAB genes) and the toxin-coregulated pilus (encoded by the tcpA gene) (10, 20). Recent studies have indicated that the ctxAB and tcpA genes may also be present in “nonepidemic” (i.e., other than O1 and O139) V. cholerae serogroups (7, 8, 9, 18, 23, 24, 26). While the genetic relatedness of O1 and O139 isolates has been well documented (1, 2, 3, 12), we know less about the genetic relatedness and phylogeny of ctxAB- and tcpA-positive isolates in other serogroups, and such data are critical for understanding why and how pandemic-causing V. cholerae strains emerge.

Several molecular typing approaches, including ribotyping (28), insertion sequence-based fingerprinting (3), amplified fragment length polymorphism (17), and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) (6), have been used to characterize the molecular epidemiology of V. cholerae, with PFGE reported (6, 8) to have the most discriminatory power among these methods. These techniques have less utility in defining underlying phylogenetic relationships (11). Multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (MLEE) is of value in this regard (12), although problems with band resolution and the fact that phenotypic expression of the enzyme under study can easily be altered in response to environmental conditions can adversely affect the reproducibility of MLEE results and complicate data analysis and interpretation.

More recently, attention has turned to sequence-based approaches. Sequencing of a single gene (19, 31) is not optimal: because evolution occurs by a net-like process, gene trees based on a single gene may not permit accurate determination of the genetic relatedness among various isolates (15). Multilocus sequence typing (MLST), first described in 1998 (25), provides a balance between sequence-based resolution and informativeness and technical feasibility and has been used to characterize several pathogenic bacteria, including, in recent studies, V. cholerae (5, 13). The technique, as originally described, involves determining the nucleotide sequences of a series of housekeeping genes. MLST alleviates several problems associated with PFGE: MLST data, based as they are on nucleotide sequences, are unambiguously comparable among laboratories, and MLST detects all genetic variations within the amplified gene fragment while PFGE examines only those that are in specific restriction sites and those that involve large insertions or deletions of DNA. As variation occurs most commonly at the nucleotide level, MLST is likely to have better discriminatory ability than PFGE, as recently reported in studies with Salmonella (21).

The present study was undertaken with two goals: (i) to compare, at a methodological level, the discriminatory powers of MLST and PFGE for V. cholerae and (ii) to use MLST to assess phylogenetic clustering of tcpA- and ctxAB-positive isolates from epidemic and nonepidemic serogroups and evaluate relationships between these clusters and specific tcpA and ctxAB alleles.

Bacterial isolate collection.

The 22 V. cholerae isolates used in this study (Table 1) have been previously described (23, 24), as have methods for isolate storage and propagation (30). The presence of the tcpA and ctxAB genes was initially determined by dot blot analysis (23), followed by sequencing studies, as described below.

TABLE 1.

Sources and years and places of isolation of V. cholerae strains examined, serogroups and PFGE and sequence types of the strains, and allele types of ctxAB and tcpA genes

| Strain | Serogroup | PFGE type | Sequence type | Source | Place/year of isolation | Allele type designation for virulence gene(s):

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tcpA | ctxAB | ||||||

| 117-94 | O35 | P7 | ST21 | Environment | Korea/1994 | ||

| 984-81 | O89 | P13 | ST7 | Diarrhea | India/1981 | ||

| AM2 | O9 | P2 | ST6 | Diarrhea | India/1995 | ||

| AM107 | O144 | P11 | ST10 | Diarrhea | India/1996 | ||

| NRT36-S | O31 | P8 | ST11 | Diarrhea | Japan/1990 | ||

| 981-75 | O65 | P1 | ST17 | Diarrhea | India/1975 | T1 | |

| 8585 | O53 | P1 | ST17 | Diarrhea | Iraq/1969 | T1 | |

| 8-76 | O77 | P12 | ST5 | Diarrhea | India/1976 | T4 | |

| 1421-77 | O80 | P4 | ST4 | Diarrhea | India/1977 | T4 | |

| AQ1875 | O48 | P5 | ST20 | Food | Japan/1998 | T9 | |

| 1322-69 | O37 | P5 | ST18 | Diarrhea | India/1969 | T5 | C5 |

| N16961 | O1 E1 Tor | P5 | ST15 | Diarrhea | Bangladesh/1975 | T1 | C3 |

| 365-96 | O27 | P6 | ST16 | Food | Japan/1996 | T3 | C1 |

| NIH35A3 | O1 classical | P10 | ST14 | Diarrhea | India/1941 | T5 | C2 |

| 507-94 | O49 | P5 | ST12 | Diarrhea | Thailand/1994 | T10 | C3 |

| 63-93 (MO 45) | O139 | P9 | ST13 | Diarrhea | India/1992 | T1 | C3 |

| 153-94 | O8 | P5 | ST19 | Unknown | Unknown/1994 | T8 | C3 |

| 203-93 | O141 | P10 | ST1 | Diarrhea | India/1993 | T6 | C4 |

| No. 63 | O26 | P10 | ST2 | Diarrhea | Japan/1991 | T7 | C1 |

| 506-94 | O44 | P5 | ST3 | Diarrhea | Thailand/1994 | T1 | C3 |

| 571-88 | O105 | P3 | ST8 | Diarrhea | China/1988 | T3 | C6 |

| 366-96 | O191 | P5 | ST9 | Diarrhea | Japan/1996 | T2 | C2 |

PFGE analysis.

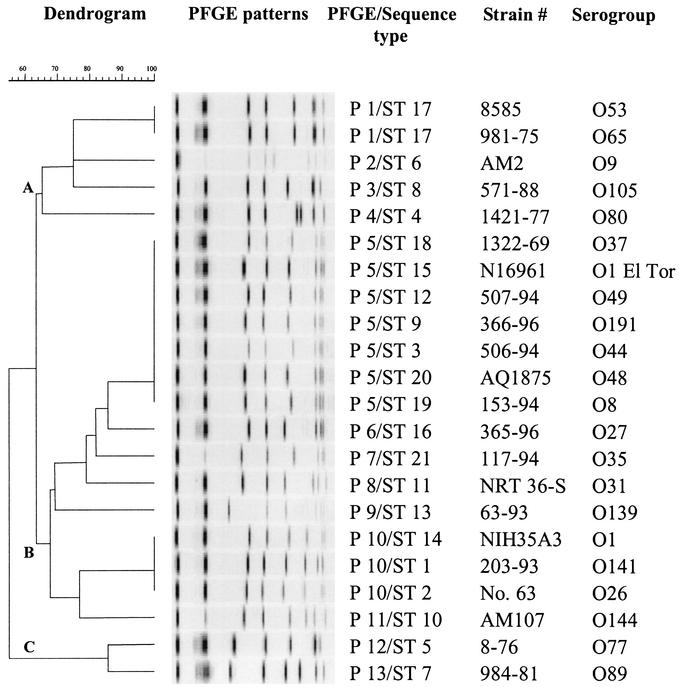

Plugs containing V. cholerae DNA were prepared (6), and CeuI macrorestriction patterns were obtained after electrophoresis in the CHEF DR II apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) under the following conditions: voltage, 180 V; initial time, 2.2 s; final time, 64 s; and run time, 20 h. We elected to use CeuI instead of, for example, NotI (which is more frequently used to type V. cholerae) because NotI restriction digestion of V. cholerae DNA generates numerous bands and it is very difficult to resolve multiple bands of similar sizes in NotI-generated PFGE patterns, which complicates data analysis, including the construction of rigorous dendrograms. CeuI generates anywhere from 6 to 10 bands from V. cholerae DNA, and the bands can be separated very well by using the electrophoresis conditions used during our study. Also, CeuI has been shown (27) to provide an excellent tool for rapidly examining the organization of genomes of various serovars and biovars of V. cholerae. A dendrogram (Fig. 1) was constructed with Fingerprinting DST Molecular Analyst software (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The patterns were compared by means of the Jaccard coefficient of band-based similarity by using the unweighted pair group method using averages (a tolerance of 3% in band position was applied). Thirteen PFGE types were identified among the 22 isolates examined (Table 1). PFGE types P1, P5, and P10 contained two, seven, and three isolates, respectively, with identical PFGE patterns, while each of the remaining 10 isolates had unique PFGE patterns. The isolates were grouped in three major PFGE clusters at the 64% similarity level (Fig. 1). Cluster A contained 5 isolates, cluster B contained 15 isolates (including the O1 and O139 serogroup isolates), and cluster C contained 2 isolates.

FIG. 1.

Dendrogram portraying the genetic diversity of various V. cholerae isolates. The dendrogram is based on PFGE patterns obtained with CeuI-digested V. cholerae DNA.

Within cluster B, serogroup O1 classical, O1 El Tor, and O139 isolates were grouped into distinct, but closely related, PFGE types (PFGE types P10, P5, and P9, respectively). However, PFGE did not differentiate among (i) the O1 classical, O141, and O26 serogroups, all of which were grouped in the P10 type, and (ii) the O1 El Tor, O37, O49, O191, O44, O48, and O8 serogroups, all of which were grouped in a single PFGE type, P5 (Fig. 1). Isolates from some serogroups that cluster by PFGE (e.g., O1 El Tor and O8) appear in different MLEE lineages (1). At the same time, some serogroups (e.g., O1 and O139) known to be very closely related genetically (1, 2, 3) were grouped in distinct types during our PFGE analysis. These observations suggest that conclusions about the genetic relatedness of V. cholerae isolates based on PFGE analysis must be interpreted with caution, as suggested previously for other bacteria (11).

MLST analysis.

Six loci (Table 2) were sequenced, including regions from three housekeeping genes (the genes encoding the B subunit of DNA gyrase [gyrB], recombination protein [recA], and phosphoglucomutase [pgm]) and three virulence-related genes (those encoding the A and B subunits of cholera toxin [ctxA and ctxB, respectively], present in 12 isolates, and that encoding the toxin-coregulated pilus [tcpA], present in 17 isolates). The same primers were used for PCR amplification and sequencing, and they were designed with the basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST) and ClustalX (16) programs. Sequencing of amplified fragments was performed in both directions by using an ABI 3700 DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, Calif.). The sequence type analysis and recombinational tests (START) program (http://outbreak.ceid.ox.ac.uk) was used to determine the G+C content, the numbers of alleles and polymorphic sites, and the proportions of nonsynonymous and synonymous base substitutions (dN and dS, respectively) for the genes examined during our study.

TABLE 2.

Primers used for MLST of V. cholerae strains, numbers of alleles and polymorphic sites identified per gene, and dN/dS ratios for various genes

| Gene | Primer set (5′ → 3′) | No. of strains | Fragment length (bp)

|

No. of alleles | No. of polymorphic sites | Mean G+C content (%) | dN/dS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amplified | START analyzed | |||||||

| ctxA | GGCTGTGGGTAGAAGTGAAACGG, CTAAGGATGTGGAATAAAAACATC | 12 | 1,140 | 770 | 6b | 1 | 38.5 | 0.0000 |

| ctxBa | 12 | 360 | 4 | 33.6 | 0.0087 | |||

| tcpAc | AAAACCGGTCAAGAGGG, CAAAAGCTACTGTGAATGG, CAAATGCAACGCCGAATGG | 17 | 600 | 300 | 10 | 140 | 43.6 | 0.0579 |

| gyrB | GAAGGBGGTATTCAAGC, GAGTCACCCTCCACWATGTA | 22 | 560 | 460 | 12 | 16 | 51.2 | 0.000 |

| pgm | AAAGATACTCAYGCSCTGTC, AACCAGCGTTTTACCGACGGCAACA | 22 | 730 | 540 | 13 | 19 | 49.2 | 0.0262 |

| recA | GAAACCATTTCGACCGGTTC, CCGTTATAGCTGTACCAAGCGCCC | 22 | 700 | 380 | 14 | 35 | 49.5 | 0.0069 |

The ctxAB primers have been described in reference 23. The amplified 1,140-bp region includes ctxA and ctxB loci.

The allele number shown here and the ctxAB allele numbers and designations used throughout the text, Fig. 2, and Table 1 are based on the combined sequence of the ctxA and ctxB loci.

A mixture of two previously described (20) reverse primers was used to amplify the tcpA gene.

Sequence analysis of housekeeping genes.

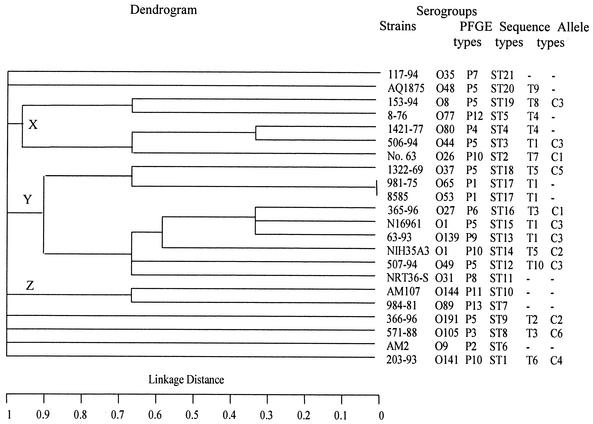

Analysis of sequence data for gyrB, pgm, and recA from our 22 isolates resulted in the identification of 12, 13, and 14 allelic variants, respectively. Twenty-one unique sequence types were identified among these 22 isolates, based on the allelic profiles (Table 1). The genetic relatedness of isolates based on various sequence types was determined by START by using the unweighted pair group method using averages. The resulting dendrogram revealed three clusters (Fig. 2), designated X, Y, and Z. Of note, the three epidemic serogroup isolates were found to cluster in a single subgroup within the largest cluster (cluster Y). The cluster also included several isolates from nonepidemic serogroups, some of which were ctxAB negative (e.g., isolate 981-75) or tcpA and ctxAB negative (e.g., isolate NRT36-S). Although the number of isolates analyzed was small, there was no obvious correlation between cluster patterns and dates or countries of isolation.

FIG. 2.

Dendrogram portraying the genetic diversity among various V. cholerae sequence types, constructed by the unweighted pair group method using averages. Allele types are for tcpA and ctx, respectively.

Sequence analysis of virulence genes.

Ten allele types were identified among the 17 tcpA-positive isolates, and six allele types were identified among the 12 ctxAB-positive isolates (Table 1). tcpA had the largest number of polymorphic sites among the six genes that we analyzed (Table 2), which is in agreement with previously reported data (4, 24) about the genetic variability of tcpA genes. In contrast, the numbers of polymorphic sites were very low in ctxA and ctxB (one and four, respectively). There were differences in the G+C contents of the ctxA and ctxB regions (38.5 and 33.6%, respectively; Table 2).

Four of the five tcpA T1 alleles were within the Y cluster in the dendrogram, as were both T5 alleles; both tcpA T4 alleles were in cluster X. At the same time, the T3 allele was found in cluster Y and in a second isolate outside of all three clusters. As expected, given that tcpA is a receptor for the ctx phage, the ctx gene was found only in tcpA-positive strains. The ctxAB allele C3 was associated with the tcpA T1 allele in three instances (the O139 and O1 El Tor isolates in cluster Y and an O44 isolate in cluster X). In all other instances, the same ctxAB allele was associated with different tcpA alleles.

Recombinational basis of genetic diversity of loci analyzed by MLST.

With the exception of the ctxA and ctxB regions, which were relatively homogeneous, considerable sequence variability was observed within the sequenced gene regions (Table 2). The dN/dS ratios were less than one for all of the genes examined, which suggests that selective pressure for nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions was not the primary driving force during the diversification of the genes. Thus, we used Splitstree analysis (http://bibiserv.techfak.uni-bielefeld.de/splits) to determine whether recombinational changes were likely to have contributed to the genetic heterogeneity of the genes that we analyzed.

In the Splitsgraph, recombination is depicted by parallelograms; i.e., the observation that parallelograms are formed during Splitstree analysis indicates that recombination may have been involved in the evolution of the analyzed gene. During our analysis, we observed parallelograms for five of the six genes examined (the ctxA analysis did not reveal parallelograms and, thus, any supportive evidence of recombination in the gene) (data not shown). Genetic recombination has been described (5) to occur in other housekeeping genes of V. cholerae, and our Splitstree results suggest that it has also occurred in the three housekeeping genes analyzed during our study.

Isolates 981-75 and 8585 had identical sequence types and the same tcpA allele type (T1), were both ctxAB negative, and were grouped into a single PFGE type (P1); however, they belong to two distinct serogroups (O65 and O53, respectively). This observation is in keeping with other reports (3, 23) of O-antigen switching among isolates with a common genetic background, consistent with the hypothesis that the O-antigen-encoding genes are readily transferred among isolates via genetic recombination.

Discriminatory ability of MLST versus that of PFGE.

Thirteen PFGE types were identified among the 22 isolates analyzed during our study, whereas the number of sequence types was larger (21 sequence types; Table 1), an observation which suggests that the discriminatory ability of MLST is better than that of PFGE. The O1 classical, O1 El Tor, and O139 isolates of V. cholerae examined during our study were differentiated by both PFGE and MLST. However, several isolates within the same PFGE types (i.e., indistinguishable by PFGE typing) were differentiated into separate sequence types by MLST (but not vice versa). For example, each of the seven V. cholerae isolates (1322-69, N16961, 507-94, 366-96, 506-94, AQ1875, and 153-94) grouped together in PFGE type P5 (Fig. 1) had a unique sequence type (Table 1). At the same time, the two isolates (981-75 and 8585) with identical sequence types (ST17) could not be differentiated with PFGE (Table 1). The increased discriminatory power of MLST was apparent even though we used only three housekeeping genes; the addition of more loci will only increase the discriminatory power of the method.

In order to compare further the discriminatory abilities of MLST and PFGE, we analyzed the linkage distances among the isolates grouped in each of the three PFGE types containing more than one isolate (i.e., PFGE types P1, P5, and P10). Linkage distances were consistently larger than 0.35 (the minimal linkage distance identified in the dendrogram for the isolates in distinct sequence types) (Fig. 2); e.g., linkage distances for the seven isolates grouped in PFGE type P5 varied from 0.65 to 1.

Summary.

At a methodological level, and in agreement with findings with other species (21), our data suggest that MLST has better discriminatory ability than PFGE for typing V. cholerae. Our secondary objective was to further explore relationships among virulence marker-carrying isolates in epidemic and nonepidemic serogroups. To do this, we looked at phylogenetic relationships among isolates as defined by sequence types (based on allelic variants of three housekeeping genes) and then assessed allelic variation of tcpA and ctxAB genes in the context of the resulting phylogenetic tree. While there was definite clustering of the epidemic O1 and O139 isolates based on MLST analysis of housekeeping genes, no other clear patterns emerged: tcpA and ctxAB genes were present in nonepidemic serotypes with a variety of MLST sequence types, suggesting that acquisition of these virulence markers is not restricted to a subset of closely related V. cholerae strains. There were suggestions that certain tcpA allelic types were more common among epidemic isolates and clusters. However, there was also fairly extensive mixing of sequence types, tcpA allelic types, and ctxAB allelic types, consistent with the reported mobility of certain elements (i.e., ctxAB [32]) and the hypothesis that recombinational events are not an infrequent occurrence among V. cholerae strains.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The DNA sequences have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers AF501888 through AF501909 for the gyrB se-quences; AF536843 through AF536864 for the pgm sequences; AF301032, AF301042, AF301050, AF301052, AF301055, AF301063, AF301080, AF301086, AF301105, AF301123, AF301131, AF501905, AF536832 through AF536838, and AF536840 through AF536842 for the recA sequences; AF390572, AF452584, AF463400, and AF463401 for the ctxA gene sequences (isolate NIH35A3 sequences are identical to those of previously characterized isolate 569B [accession number X58785], and the sequences of the remaining isolates are identical to those of isolate N16961 [accession number AE004224] [14]); AF390572, AF452581, AF452582, AF452583, and AF463402 for the ctxB sequences (isolates NIH35A3, 203-93, and 366-96 have sequences identical to those of isolate 569B [accession number X58785], and isolates 507-94, 63-93, and 153-94 have sequences identical to those of isolate N16961 [accession number AE004224] [14]); and AF390571, AF452570 through AF452577, AF452579, AF452580, and AF536865 through AF536870 for the tcpA sequences.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from NIGMS (RO1 GM60791) and a BTEP 10/ISTC G597 grant from the DHHS Biotechnology Engagement Program. M.K. was supported by an International Training and Research in Emerging Infectious Diseases grant from the Fogarty International Center, National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beltran, P., G. Delgado, A. Navarro, F. Trujillo, R. K. Selander, and A. Cravioto. 1999. Genetic diversity and population structure of Vibrio cholerae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:581-590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berche, P., C. Poyart, E. Abachin, H. Lelievre, J. Vandepitte, A. Dodin, and J. M. Fournier. 1994. The novel epidemic isolate O139 is closely related to the pandemic isolate O1 of Vibrio cholerae. J. Infect. Dis. 170:701-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bik, E. M., R. D. Gouw, and F. R. Mooi. 1996. DNA fingerprinting of Vibrio cholerae isolates with a novel insertion sequence element: a tool to identify epidemic isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:1453-1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyd, E. F., and M. K. Waldor. 2002. Evolutionary and functional analyses of variants of the toxin-coregulated pilus protein TcpA from toxigenic Vibrio cholerae non-O1/non-O139 serogroup isolates. Microbiology 148:1655-1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byun, R., L. D. H. Elbourne, R. Lan, and P. R. Reeves. 1999. Evolutionary relationships of pathogenic clones of Vibrio cholerae by sequence analysis of four housekeeping genes. Infect. Immun. 67:1116-1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cameron, D. N., F. M. Khambaty, I. K. Wachsmuth, R. V. Tauxe, and T. J. Barrett. 1994. Molecular characterization of Vibrio cholerae O1 isolates by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:1685-1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chakraborty, S., A. K. Mukhopadhyay, R. K. Bhadra, A. N. Ghosh, R. Mitra, T. Shimada, S. Yamasaki, S. M. Faruque, Y. Takeda, R. R. Colwell, and G. B. Nair. 2000. Virulence genes in environmental isolates of Vibrio cholerae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4022-4028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalsgaard, A., M. N. Skov, O. Serichantalergs, and P. Echeverria. 1996. Comparison of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and ribotyping for subtyping of Vibrio cholerae O139 isolated in Thailand. Epidemiol. Infect. 117:51-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalsgaard, A., O. Serichantalergs, A. Forslund, W. Lin, J. Mekalanos, E. Mintz, T. Shimada, and J. G. Wells. 2001. Clinical and environmental isolates of Vibrio cholerae serogroup O141 carry the CTX phage and the genes encoding the toxin-coregulated pili. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4086-4092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dziejman, M., E. Balon, D. Boyd, C. M. Fraser, J. F. Heidelberg, and J. J. Mekalanos. 2002. Comparative genomic analysis of Vibrio cholerae: genes that correlate with cholera endemic and pandemic disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:1556-1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enright, M. C., and B. G. Spratt. 1999. Multilocus sequence typing. Trends Microbiol. 7:482-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farfan, M., D. Minana, M. C. Fuste, and J. G. Loren. 2000. Genetic relationships between clinical and environmental Vibrio cholerae isolates based on multilocus enzyme electrophoresis. Microbiology 146:2613-2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farfan, M., D. Minana-Galbis, M. C. Fuste, and J. G. Loren. 2002. Allelic diversity and population structure in Vibrio cholerae O139 Bengal based on nucleotide sequence analysis. J. Bacteriol. 184:1304-1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heidelberg, J. F., J. A. Eisen, W. C. Nelson, R. A. Clayton, M. L. Gwinn, R. J. Dodson, D. H. Haft, E. K. Hickey, J. D. Peterson, L. Umayam, S. R. Gill, K. E. Nelson, T. D. Read, H. Tettelin, D. Richardson, M. D. Ermolaeva, J. Vamathevan, S. Bass, H. Qin, I. Dragoi, P. Sellers, L. McDonald, T. Utterback, R. D. Fleishmann, W. C. Nierman, and O. White. 2000. DNA sequence of both chromosomes of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Nature 406:477-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holmes, E. C., R. Urwin, and M. C. Maiden. 1999. The influence of recombination on the population structure and evolution of the human pathogen Neisseria meningitidis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16:741-749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeanmougin, F., J. D. Thompson, M. Gouy, D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1998. Multiple sequence alignment with Clustal X. Trends Biochem. Sci. 23:403-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang, S. C., V. Louis, N. Choopun, A. Sharma, A. Huq, and R. R. Colwell. 2000. Genetic diversity of Vibrio cholerae in Chesapeake Bay determined by amplified fragment length polymorphism fingerprinting. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:140-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamal, A. M. 1971. Outbreak of gastro-enteritis by non-agglutinale (NAG) vibrios in the Republic of the Sudan. J. Egypt. Public Health Assoc. XLVI:125-159.

- 19.Karaolis, D. K., R. Lan, and P. R. Reeves. 1995. The sixth and seventh cholera pandemics are due to independent clones separately derived from environmental, nontoxigenic, non-O1 Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 177:3191-3198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karaolis, D. K., J. A. Johnson, C. C. Bailey, E. C. Boedeker, J. B. Kaper, and P. R. Reeves. 1998. A Vibrio cholerae pathogenicity island associated with epidemic and pandemic isolates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:3134-3139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kotetishvili, M., O. C. Stine, A. Kreger, J. G. Morris, Jr., and A. Sulakvelidze. 2002. Multilocus sequence typing for characterization of clinical and environmental Salmonella isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1626-1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lacey, S. W. 1995. Cholera: calamitous past, ominous future. Clin. Infect. Dis. 20:1409-1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li, M., T. Shimada, J. G. Morris, Jr., A. Sulakvelidze, and S. Sozhamannan. 2002. Evidence for the emergence of non-O1/non-O139 Vibrio cholerae isolates with pathogenic potential by exchange of O-antigen biosynthesis regions. Infect. Immun. 70:2441-2453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li, M., M. Kotetishvili, Y. Chen, and S. Sozhamannan. 2003. Comparative genomic analyses of the vibrio pathogenicity island and cholera toxin prophage regions in nonepidemic serogroup strains of Vibrio cholerae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:1728-1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maiden, M. C. J., J. A. Bygraves, E. Feil, G. Morelli, J. E. Russell, R. Urwin, Q. Zhang, J. Zhou, K. Zurth, D. A. Caugant, I. M. Feavers, M. Achtman, and B. G. Spratt. 1998. Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:3140-3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mukhopadhyay, A. K., S. Chakraborty, Y. Takeda, G. B. Nair, and D. E. Berg. 2001. Characterization of VPI pathogenicity island and CTX prophage in environmental isolates of Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 183:4737-4746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nandi, S., G. Khetawat, S. Sengupta, R. Majumder, S. Kar, R. K. Bhadra, S. Roychoudhury, and J. Das. 1997. Rearrangements in the genomes of Vibrio cholerae strains belonging to different serovars and biovars. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 47:858-862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Popovic, T., C. Bopp, O. Olsvik, and K. Wachsmuth. 1993. Epidemiologic application of a standardized ribotype scheme for Vibrio cholerae O1. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:2474-2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimada, T., E. Arakawa, K. Itoh, T. Okitsu, A. Matsushima, Y. Asai, S. Yamai, T. Nakazato, G. B. Nair, M. J. Albert, and Y. Takeda. 1994. Extended serotyping scheme for Vibrio cholerae. Curr. Microbiol. 28:175-178. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sozhamannan, S., Y. K. Deng, M. Li, A. Sulakvelidze, J. B. Kaper, J. A. Johnson, G. B. Nair, and J. G. Morris, Jr. 1999. Cloning and sequencing of the genes downstream of the wbf gene cluster of Vibrio cholerae serogroup O139 and analysis of the junction genes in other serogroups. Infect. Immun. 67:5033-5040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stine, O. C., S. Sozhamannan, Q. Gou, S. Zheng, J. G. Morris, Jr., and J. A. Johnson. 2000. Phylogeny of Vibrio cholerae based on recA sequence. Infect. Immun. 68:7180-7185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waldor, M. K., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1996. Lysogenic conversion by a filamentous phage encoding cholera toxin. Science 272:1910-1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]