Abstract

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) of SmaI macrofragments and hybridization of ClaI digests with the mecA- and Tn554-specific DNA probes were used to define the endemic clones of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) among strains collected in 1993 and 1998 to 2000 at the University Hospital of Patras, Patras, Greece. Representatives of each clonal type were analyzed by spaA typing, multilocus sequence typing (MLST), and staphylococcal chromosomal cassette mec (SCCmec) typing. The results indicated the existence of two successive international MRSA clones: (i) a clonal type with PFGE type A, sequence type (ST) 30 (ST30), and SCCmec type IV, which was very similar to a clone widely spread in the United Kingdom, Mexico, and Finland, and (ii) a clonal type with PFGE type B, ST239, and SCCmec III, which was related to the Brazilian clone. Both clones seem to be widespread in Greece as well. A novel MRSA clone is also described and is characterized by a new MLST type (ST80) associated with SCCmec type IV and with the presence of Panton-Valentine leukocidin genes.

In Greece, as in many other countries, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) remains a major cause of nosocomial infection. Kosmidis et al. (16) reported an MRSA frequency of 32% (range, 17 to 60%) in 1986 in a study that included 12 hospitals in Athens. Ten years later, the prevalence of MRSA was estimated to be 12 to 50% among 28 hospitals (39), and in 1997 the prevalence was 41% in a study that included 7 hospitals in the Athens area (15). Therefore, the prevalence of MRSA in Greece seems to be among the highest in Europe at present (12). Reports from Greece documenting the clonality of MRSA isolates are still scarce, the hospitals studied were mostly from the Athens and Thessaloniki areas, and molecular typing was mainly based on pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) alone. Tassios et al. (36) reported two major MRSA clones, identified by PFGE, among isolates collected in 1990 in a large University Hospital in Athens, where the rate of MRSA infections was estimated to be 25%. In a more recent study involving strains collected during 1999 and 2000 in the five major hospitals of the district of Thessaly, PFGE distributed the MRSA isolates into three pulsotypes (28).

Multiple DNA-based methods have been introduced to genetically type S. aureus strains and to track the dissemination of MRSA clones. During the last decade, five major internationally spread MRSA clones, the Iberian (8, 34), Brazilian (37), Hungarian (7, 23), New York-Japan (1, 31), and pediatric (32) clones, were identified by using the combination of ClaI-mecA polymorphisms, Tn554 insertion patterns, and PFGE. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) has recently been proven to be the most adequate method both for long-term and global epidemiologic studies and for population genetic studies (10, 27), whereas for short-term or local epidemiologic studies of S. aureus, PFGE continues to be the method of choice (27). MLST combined with staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) typing established that there are relatively few major epidemic MRSA clones (11, 26).

The aim of this study was to define the MRSA clonal types and their evolution over time in a teaching hospital in Patras (southwestern Greece) by different molecular typing methods, including ClaI-mecA polymorphism analysis, Tn554 insertion pattern analysis, PFGE, spaA typing, MLST, and SCCmec typing. A comparison with representatives of two major clones previously identified in Greece was also done.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Hospital.

The University Hospital of Patras is a 750-bed tertiary-care teaching hospital that receives patients from the southwestern part of Greece. The frequency of MRSA infections in the hospital decreased significantly from 1993 to 2000 (38.0% in 1993, 17 to 18% in 1998 and 1999, and 14.7% in 2000), probably due to the implementation of several infection control policies, such as a decrease in the inappropriate use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, together with an emphasis on hand washing.

Bacterial isolates.

One hundred eighteen MRSA isolates collected from single patients during 1998 (40 isolates), 1999 (31 isolates), and 2000 (37 isolates) as well as 10 isolates collected in the first trimester of 1993 were analyzed. The isolates were from patients on a range of wards and comprised 45 isolates from blood cultures, 25 isolates from catheter-related infections, and 48 isolates from wound samples. The isolates were confirmed to be MRSA by hybridization with the mecA probe (6). The following reference strains were used in this study: A3680 (36), HPV107 (34), HU25 (37), MCO58 (2), EMRSA-16 (Harmony Project [www.phls.org.uk/International/Harmony/Harmony.htm)], and 75916-Helsinki V (Harmony Project). The strains belong to the collection of the Molecular Genetics Laboratory, Instituto de Tecnologia Química e Biológica da Universidade Nova de Lisboa.

Susceptibility tests.

Susceptibility tests were performed by the standard disk diffusion method with the computer software SIRSCAN 2000 (Becton Dickinson, Aalst, Belgium), according to National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards guidelines (19), with ampicillin, oxacillin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, imipenem, amikacin, netilmicin, erythromycin, ciprofloxacin, fusidic acid, and sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (Oxoid, Basingstoke, England). The MICs of oxacillin and vancomycin (Sigma Chemical Co, Steinheim, Germany) were determined by the agar dilution method (18). Resistance to 500 mg of spectinomycin per liter was evaluated as described previously (1).

β-Lactamase assay.

The production of β-lactamase was tested with nitrocefin disks (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

PVL detection.

Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) genes were detected by PCR, as described elsewhere (9).

Molecular typing.

Southern blot hybridization of ClaI digests with mecA- and Tn554-specific DNA probes (6), PFGE of SmaI digests of chromosomal DNAs (6), spaA typing (35), and MLST (10) were performed as described previously. When the PFGE results were interpreted, one to six band differences defined a PFGE subtype and seven or more band differences defined a distinct PFGE type (38). The primers used for spaA typing were as follows: primer spaAF1 (GAC GAT CCT TCG GTG AGC; nucleotides 1096 to 1113) and primer spaAR1 (CAG CAG TAG TGC CGT TTG C; nucleotides 1534 to 1516) (GenBank accession number J01786) (23). Previously described primers were adopted for MLST (10); the exception was primer arcCF2 (CCT TTA TTT GAT TCA CCA GCG; the forward primer for the arcC gene) (5). The SCCmec types were determined by a multiplex PCR strategy (24) or by PCR amplification of the ccr (cassette chromosome recombinase) gene (13, 21) and the mec gene complex (21) when at least one of the structural features shown to be typical of a particular SCCmec type was not identified by the multiplex PCR strategy.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The antimicrobial resistance patterns varied among the isolates and were related to the PFGE types (Table 1). Strains of PFGE type B (see below) were mainly multiresistant, expressing resistance to more than three different classes of antibiotics, including quinolones and fusidic acid. Strains belonging to PFGE types A and C (see below) were resistant to β-lactams only, and almost all isolates of PFGE type C expressed, in addition, resistance to fusidic acid. For most isolates resistant to β-lactams only, oxacillin MICs seemed to be much lower than those for the multiresistant isolates, which had already been observed for isolates belonging to the pediatric MRSA clone (32). All isolates were resistant to ampicillin, and β-lactamase production was detected in 113 of 118 (96%) MRSA isolates. Among the strains carrying Tn554, only the one with Tn554::E expressed resistance to 500 mg of spectinomycin per liter; similarly to what was described before for strains with Tn554::B (3, 22), the strains with Tn554::KK were spectinomycin susceptible. All isolates were susceptible to netilmicin and vancomycin.

TABLE 1.

Phenotypic and genotypic properties of MRSA strains from different inpatients at the University Hospital of Patras, Patras, Greece

| Clonal typea (ClaI-mecA type:: Tn554 type:: PFGE type) | Antibiotic resistanceb | Oxacillin MIC (mg/liter) | Yr of isola- tion | No. (%) of isolates | spaA type | Allelic profiled | ST | SCCmec type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VII′::NH::A | Amp, Oxa, Amc, Ipm | 4-256 | 1993 | 7 | WGKAKAOMQQQ | IV variante | ||

| Amp, Oxa, Amc, Ipm | 64-1,024 | 1998 | 14 | WGKAKAOMQQQ | 2-2-2-2-6-3-2 | 30 | IV variante | |

| Amp, Oxa, Amc, Ipm | 64-1,024 | 1999 | 8 | WGKAKAOMQQQQ | 2-2-2-2-6-3-2 | 30 | IV variante | |

| Amp, Oxa, Amc, Ipm | ≥1,024 | 2000 | 5 | WGKAKAOMQQQ | IV variante | |||

| Total PFGE type A | 34 (29) | |||||||

| X′::KK::B | Amp, Oxa, Amc, Ipm, Ery, Cip, Fd, Sxt | ≥128 | 1998 | 13 | WGKAOMQ | 2-3-1-1-4-4-3 | 239 | IIIA |

| Amp, Oxa, Amc, Ipm, Ery, Cip, Fd, Sxt | >1,024 | 1999 | 12 | XKAOMQ | 2-3-1-1-4-4-3 | 239 | IIIA | |

| Amp, Oxa, Amc, Ipm, Ery, Cip, Fd, Sxt | ≥1,024 | 2000 | 16 | XKAOMQ | IIIA | |||

| III′::KK::B | Amp, Oxa, Amc, Ipm, Ery, Cip, Fd, Sxt | ≥128 | 1998 | 11 | WGKAOMQ | 2-3-1-1-4-4-3 | 239 | III |

| Amp, Oxa, Amc, Ipm, Ery, Cip, Fd, Sxt | ≥1,024 | 1999 | 9 | WGKAOMQ | III | |||

| Amp, Oxa, Amc, Ipm, Ery, Cip, Fd, Sxt | >1,024 | 2000 | 3 | NDf | III | |||

| III::KK::B | Amp, Oxa, Amc, Ipm, Cip, Fd, Sxt, Amk | 128-256 | 1993 | 2 | WGKAOMQ | III | ||

| Amp, Oxa, Amc, Ipm, Ery, Cip, Fd, Sxtc | ≥1,024 | 1999 | 2 | WGKAOMQ | III | |||

| Amp, Oxa, Amc, Ipm, Ery, Cip, Fd, Sxt | >1,024 | 2000 | 3 | WGKAOMQ | III | |||

| Total PFGE type B | 71 (60) | |||||||

| II::NH::C | Amp, Oxa, Amc, Ipm, Ery | 64 | 1998 | 1 | UJGBBPB | 1-3-1-14-11-51-10 | 80 | IV |

| Amp, Oxa, Amc, Ipm, Fd | ≥32 | 2000 | 10 | UJGBBPB | 1-3-1-14-11-51-10 | 80 | IV | |

| Total PFGE type C | 11 (9) | |||||||

| II::E::D | Amp, Oxa, Amc, Ipm, Ery, Sxt, Spc | 8 | 1993 | 1 | YGFMBQBLPO | 3-3-1-1-4-4-3 | 8 | IV |

| III::B::E | Amp, Oxa, Amc, Ipm, Ery, Sxt | 16 | 1998 | 1 | XKAOMMQ | 2-3-1-1-4-4-3 | 239 | III |

The ClaI-mecA::Tn554 polymorphs molecular sizes of the respective hybridization fragments were as follows: II, III (17), and III′ (2.2 and 4.05 kb); VII′ (2.2 and 7.6 kb); and X′ (2.2 and 5.9 kb). The Tn554 polymorphs were as follows: NH, no homology (lack of transposon); B and E (17); and KK, novel pattern (7.4 kb).

The panel of antimicrobials included ampicillin (Amp), oxacillin (Oxa), amoxicillin clavulanic acid (Amc), imipenem (Ipm), erythromycin (Ery), ciprofloxacin (Cip), fusidic acid (Fd), sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (Sxt), amikacin (Amk), and spectinomycin (Spc).

One isolate was susceptible to erythromycin, ciprofloxacin, fusidic acid, and sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim.

Allelic profile assignment (arcC-aroE-glpF-gmk-pta-tpi-yqiL) (10).

The SCCmec type was determined by PCR amplification of the ccr gene (13, 21) and the mec gene complex (21) when the SCCmec type could not be inferred by the multiplex PCR strategy (24).

ND, not determined.

While the 118 MRSA isolates could be separated into five ClaI-mecA polymorphs, the majority of the isolates were characterized by ClaI-mecA types X′ (n = 41; 35%) or VII′ (n = 34; 29%), which are small variations of previously described patterns X and VII, respectively (8). The isolates were classified into three ClaI-Tn554 polymorphs, but the great majority had no homology (NH) with the transposon (n = 45; 38%) or shared polymorph KK (n = 71; 60%); polymorph KK is described for the first time in this study and showed a single hybridization band of approximately 7.4 kb (Table 1).

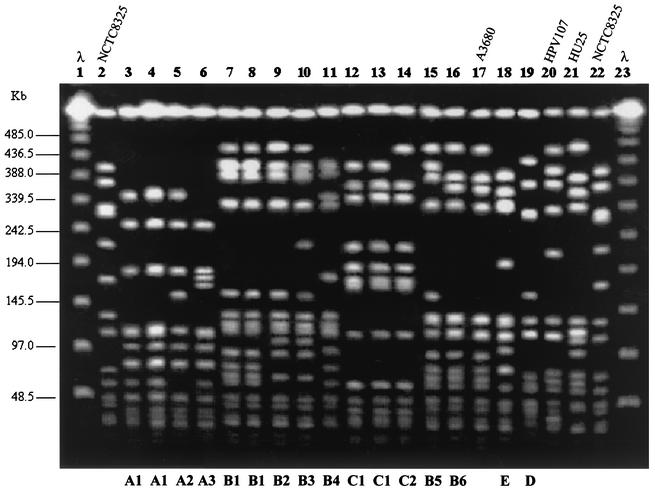

PFGE analysis grouped the 118 MRSA strains into five types (Table 1 and Fig. 1), of which 29% had pattern A, 60% had pattern B, and 9% had pattern C. Patterns D and E were represented by single isolates only. Among the isolates with pattern B there were 23 different subtypes, and among the isolates with pattern A there were 10 different subtypes.

FIG. 1.

PFGE of SmaI macrorestriction fragments of MRSA clinical isolates. Lanes 1 and 23, molecular size standards (bacteriophage lambda oligomers); lanes 2 and 22, NCTC 8325; lane 17, strain A3680, representative of the Athens MRSA clone (36); lanes 20 and 21, strains HPV107 and HU25, representatives of the Iberian (34) and the Brazilian (37) clones, respectively; lane 3, GRE112; lane 4, GRE145; lane 5, GRE104; lane 6, GRE7; lane 7, GRE3; lane 8, GRE151; lane 9, GRE159; lane 10, GRE2; lane 11, GRE328; lane 12, GRE413; lane 13, GRE365; lane 14, GRE398; lane 15, GRE163; lane 16, GRE109; lane 18, GRE108; lane 19, GRE120. The letters at the bottom indicate PFGE types or subtypes.

The combination of the three molecular typing methods classified the 118 isolates into seven clonal types (ClaI-mecA type::ClaI-Tn554 type::PFGE type). However, two clones were found to be dominant: VII′::NH::A (n = 34; 29%) and X′::KK::B (n = 41; 35%) (Table 1).

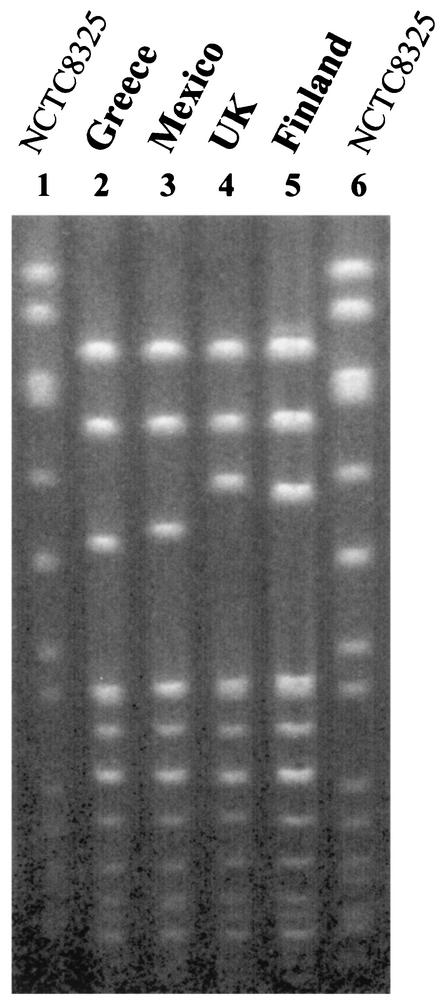

Representatives of the two major types were compared to strains belonging to previously characterized MRSA clones (Fig. 1 and 2). Clone VII′::NH::A showed a high degree of similarity with the dominant and unique clone from a pediatric hospital in Mexico, although the clone is characterized by ClaI-mecA polymorph I (2). In addition, PFGE type A is very similar to the PFGE type characteristic of a major MRSA clone (EMRSA-16) that has been shown to be disseminated in hospitals in the United Kingdom (4) and that has also been found in Finland (33) (Fig. 2). Clonal type X′::KK::B is related to the widely spread Brazilian clone (Fig. 1). However, the Brazilian MRSA clone is characterized by ClaI-mecA type XI and ClaI-Tn554 type B (2, 37). ClaI-mecA type XI differed from type X′ in the molecular size of one of the hybridization bands, which was larger in type X′ (4.3 kb for type XI and 5.9 kb for type X′), and ClaI-Tn554 type B showed three Tn554 insertions (five hybridization bands of 2.8, 3.6, 4.1, 4.9, and 8.4 kb) instead of the single one for pattern KK (a single hybridization band of 7.4 kb).

FIG. 2.

Comparison of PFGE type A with international samples. Lanes 1 and 6, NCTC 8325; lane 2, GRE5 (from Greece; this study); lane 3, MCO58 (from Mexico) (2); lane 4, EMRSA-16 (from the United Kingdom) (Harmony Project); lane 5, 75916-Helsinki V (from Finland) (Harmony Project).

Several selected isolates representing the two major clonal lineages (PFGE types A and B) were examined by spaA typing (16 isolates), MLST (five isolates), and SCCmec typing (18 isolates) (Table 1). Isolates of PFGE types A and B presented similar spaA repeat codes: WGKAKAOMQQQ and WGKAOMQ, respectively. Isolates of PFGE type A share the WGKAKAOMQQQ repeat, and strains of type B share the WGKAOMQ repeat or, less frequently, the XKAOMQ repeat. The last two repeats were very similar to the one originally described for the Hungarian and Brazilian clones (23, 25). The two PFGE types could also be distinguished by their MLST and SCCmec types: isolates of PFGE type A were characterized by sequence type (ST) 30 (ST30) and SCCmec type IV, whereas isolates of PFGE type B were characterized by ST239 and SCCmec type III or IIIA, identical to the ones described for the Hungarian and the Brazilian clones (25). Strains of ST30 were associated with a SCCmec type IV variant, since the locus internal to the dcs region, a structural feature shown to be present in SCCmec types I, II, and IV (25), was not amplified by the multiplex strategy (24); however, the SCCmec type IV variant strains shared two of the elements characteristic of SCCmec type IV, namely, ccr type 2 and the class B mec gene complex (21).

Clone ST30-IV had previously been found among only a few MRSA isolates in Sweden, Germany (11), Spain (24), and Argentina (M. Aires de Sousa et al., unpublished results). International clone EMRSA-16 is characterized by SCCmec type II and ST36, the latter of which is a single-locus variant of ST30 (11): ST36 possesses allele 2 at pta, whereas ST30 possesses allele 6.

Strains with PFGE pattern A also seem to represent the predominant clone among isolates collected during 1999 and 2000 from the five major hospitals of the district of Thessaly (in central Greece) (28). In addition, two recent studies conducted in 1999 and 2000 in Hippokration General Hospital, Thessaloniki, Greece, reported the spread of an MRSA clone that was susceptible to all non-β-lactam antibiotics and that had a PFGE pattern very similar to, if not identical to, PFGE type A (29, 30). In our study, all isolates belonging to PFGE type A were also resistant to β-lactams only, but contrary to the study of Pournaras et al. (30), in the hospital that we studied, this clone seems to have been replaced by multiple-resistant isolates characterized by PFGE type B. Three isolates (G78, G122, and G185) representing the dominant clone in Hippokration General Hospital (29, 30) were confirmed to belong to a clonal type characterized by PFGE type A, as they share the spaA motif WGKAKAOMQQQ (including the three final Q repeats) and ST30 (data not shown), suggesting the circulation of this clone, clone ST30-IV, in different regions of Greece.

PFGE type B, which was found to be the PFGE type for 60% of the isolates collected in the University of Patras during the study period (1993 and 1998 to 2000), is identical to the main clone found in Athens hospitals (36) and was also detected in hospitals of the district of Thessaly (28), confirming its capacity to spread extensively. In 1999, Kantzanou et al. (14) reported on the emergence of an MRSA isolate that displayed heterogeneous expression of reduced vancomycin susceptibility in a hospital in Athens and that had the same PFGE pattern, PFGE type B, and was described as one of the major Greek MRSA clones.

The characterization by spaA typing, MLST, and SCCmec typing of isolates belonging to minor clone II::NH::C or to sporadic isolates (II::E::D and III::B::E) showed that II::NH::C and II::E::D isolates were not related to the two major lineages (PFGE types A and B), contrary to clone III::B::E, which is related to the lineage associated with PFGE type B, and II::NH::C and II::E::D isolates might have had as a common ancestor the Brazilian clone (Table 1). Isolate II::E::D had spaA type YGFMBQBLPO, ST8, and SCCmec type IV, defined by amplification of the dcs region by multiplex PCR (24) and the presence of ccr type 2 and the mec gene complex type B (21). Therefore, isolate II::E::D was ST8-IV, a clone that is also referred to in the literature as EMRSA-2 and -6 and that was previously identified in several European countries (the United Kingdom, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, The Netherlands) and the United States (11). Clone II::NH::C was very different in genotype, being characterized by a distinct spaA type (UJGBBPB) and a new ST, ST80, which differs from the closest STs described so far (ST12, ST13, and ST63) at three of the loci used in MLST, and by the presence of SCC-IV, defined not only by the amplification of the dcs region by multiplex PCR (24) but also by the presence of ccr type 2 and mec gene complex type B (21). All isolates of this clone harbored the PVL genes. The first strain (which was recovered in 1998) was recovered from the catheter of a premature baby 1 week after birth. This baby had never been discharged from the hospital and was kept on the neonatal intensive care unit, providing evidence that the MRSA infection with the ST80-IV strain was acquired in the hospital, possibly through contact with health care workers. The strains of clonal type ST80-IV recovered in 2000 were isolated from 10 additional patients suffering from traumatic skin infections, bacteremia, renal failure, arthritis, diabetes mellitus, and cirrhosis. These isolates were recovered from patients who had been hospitalized for 3 to 20 days, suggesting again that these MRSA strains were acquired in the hospital. However, since none of the patients was screened for MRSA colonization at the time of hospital admission, we cannot completely exclude the possibility that the isolates were already carried by the patients before admission.

There is a strong association between the community-acquired S. aureus strains that cause primary skin infections and severe necrotizing pneumonia and the presence of PVL genes in those strains, and PVL genes have never been detected in MRSA isolates associated with hospital-acquired infections (9). Clone ST80-IV shows features characteristic of community-acquired MRSA strains, namely, the SCCmec type, the lack of resistance to most non-β-lactam antibiotics (21), and the presence of PVL genes (9). An Australian study reported that a hospital outbreak was due to the introduction of a strain that originated in the community into the hospital setting (20). At present, the origin of clone ST80-IV is not clear.

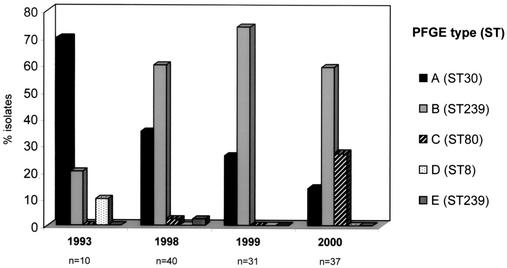

From 1993 to 2000, we observed a variation of the clonal types present in the University Hospital of Patras, namely, a progressive decrease in PFGE clone A (or ST30-IV), an increase in clone B (or ST239-III/IIIA), and the spread of clone C (ST80-IV) in 2000 (Fig. 3). Clones A and B seem to have spread in different areas of Greece and show high degrees of similarity by MLST, spaA typing, and PFGE to the international EMRSA-16 and Brazilian MRSA clones, respectively. It has already been proved that the Brazilian clone has a strong capacity to cause epidemics and the capacity to spread. When it was introduced in Portugal, it progressively replaced an existing major MRSA clone with a strong capacity to cause epidemics (3), as happened in the hospital in Patras. Clone C, which is relatively sensitive to antimicrobials but which contains the PVL genes, seems to have the capacity to cause epidemics. The large number of PFGE subtypes, as well as the variations in mecA polymorphisms and Tn554 insertion patterns, found in MRSA isolates with PFGE patterns A and B, suggest the continuous evolution of these clones.

FIG. 3.

Variations of MRSA clonal types over time in the University Hospital of Patras, Patras, Greece.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by project POCTI/1999/ESP/34872 from Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, Lisbon, Portugal, and by project SDH.IC.I.01.13 from Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon, Portugal (to H.D.L.). Two grants, grant E/027/96 from the Greek Ministry of Health and grant K. Karatheodori 1953 from Patras University, were awarded to I.S. M.A.D.S. was supported by grant BD/13731/97 from PRAXIS XXI, M.I.C. was supported by grant BD/5205/01 from the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, and I.S. received a CEM/NET fellowship from the Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon, Portugal.

We thank N. Legakis for providing MRSA strain A3680 and A. Tsakris for providing strains G78, G122, and G185. Representatives of the EMRSA-16 and Finland E5 MRSA clones were provided by the Harmony Project (contract BMH4-CT96, DGXII, led by B. Cookson). We also acknowledge M. Chung, from The Rockefeller University, for performing spaA typing and MLST of strains G78, G122, and G185 and D. Oliveira for helpful discussions concerning the SCCmec types. This publication made use of the Multi Locus Sequence Typing website (http://www.mlst.net), which is hosted at Imperial College London and at the University of Bath.

M.A.D.S. and C.B. contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aires de Sousa, M., H. de Lencastre, I. Santos Sanches, K. Kikuchi, K. Totsuka, and A. Tomasz. 2000. Similarity of antibiotic resistance patterns and molecular typing properties of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates widely spread in hospitals in New York City and in a hospital in Tokyo, Japan. Microb. Drug Resist. 6:253-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aires de Sousa, M., M. Miragaia, I. S. Sanches, S. Avila, I. Adamson, S. T. Casagrande, M. C. Brandileone, R. Palacio, L. Dell'Acqua, M. Hortal, T. Camou, A. Rossi, M. E. Velazquez-Meza, G. Echaniz-Aviles, F. Solorzano-Santos, I. Heitmann, and H. de Lencastre. 2001. Three-year assessment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones in Latin America from 1996 to 1998. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2197-2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aires de Sousa, M., I. S. Sanches, M. L. Ferro, M. J. Vaz, Z. Saraiva, T. Tendeiro, J. Serra, and H. de Lencastre. 1998. Intercontinental spread of a multidrug-resistant methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2590-2596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox, R. A., C. Conquest, C. Mallaghan, and R. R. Marples. 1995. A major outbreak of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus caused by a new phage-type (EMRSA-16). J. Hosp. Infect. 29:87-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crisostomo, M. I., H. Westh, A. Tomasz, M. Chung, D. C. Oliveira, and H. de Lencastre. 2001. The evolution of methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus: similarity of genetic backgrounds in historically early methicillin-susceptible and -resistant isolates and contemporary epidemic clones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:9865-9870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Lencastre, H., I. Couto, I. Santos, J. Melo-Cristino, A. Torres-Pereira, and A. Tomasz. 1994. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus disease in a Portuguese hospital: characterization of clonal types by a combination of DNA typing methods. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 13:64-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Lencastre, H., E. P. Severina, H. Milch, M. K. Thege, and A. Tomasz. 1997. Wide geographic distribution of a unique methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone in Hungarian hospitals. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 3:289-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dominguez, M. A., H. de Lencastre, J. Linares, and A. Tomasz. 1994. Spread and maintenance of a dominant methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) clone during an outbreak of MRSA disease in a Spanish hospital. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:2081-2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dufour, P., Y. Gillet, M. Bes, G. Lina, F. Vandenesch, D. Floret, J. Etienne, and H. Richet. 2002. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in France: emergence of a single clone that produces Panton-Valentine leukocidin. Clin. Infect. Dis. 35:819-824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Enright, M. C., N. P. Day, C. E. Davies, S. J. Peacock, and B. G. Spratt. 2000. Multilocus sequence typing for characterization of methicillin- resistant and methicillin-susceptible clones of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1008-1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enright, M. C., D. A. Robinson, G. Randle, E. J. Feil, H. Grundmann, and B. G. Spratt. 2002. The evolutionary history of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:7687-7692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System. 2002. Annual report EARSS—2001. European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System, Bilthoven, The Netherlands.

- 13.Ito, T., Y. Katayama, K. Asada, N. Mori, K. Tsutsumimoto, C. Tiensasitorn, and K. Hiramatsu. 2001. Structural comparison of three types of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec integrated in the chromosome in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1323-1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kantzanou, M., P. T. Tassios, A. Tseleni-Kotsovili, N. J. Legakis, and A. C. Vatopoulos. 1999. Reduced susceptibility to vancomycin of nosocomial isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 43:729-731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kantzanou, M., P. T. Tassios, A. Tseleni-Kotsovili, A. N. Maniatis, A. C. Vatopoulos, N. J. Legakis, et al. 1999. A multi-centre study of nosocomial methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Greece. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 12:115-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kosmidis, J., C. Polychronopoulou-Karakatsanis, D. Milona-Petropoulou, N. Mavrogenis, M. Xenaki-Kondyli, and P. Gargalianos. 1988. Staphylococcal infections in hospital: the Greek experience. J. Hosp. Infect. 11:109-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kreiswirth, B., J. Kornblum, R. D. Arbeit, W. Eisner, J. N. Maslow, A. McGeer, D. E. Low, and R. P. Novick. 1993. Evidence for a clonal origin of methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Science 259:227-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2002. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 5th ed. Approved standard M7-A5. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 19.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1999. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests, 6th ed. Approved standard M2-A6. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 20.O'Brien, F. G., J. W. Pearman, M. Gracey, T. V. Riley, and W. B. Grubb. 1999. Community strain of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus involved in a hospital outbreak. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2858-2862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okuma, K., K. Iwakawa, J. D. Turnidge, W. B. Grubb, J. M. Bell, F. G. O'Brien, G. W. Coombs, J. W. Pearman, F. C. Tenover, M. Kapi, C. Tiensasitorn, T. Ito, and K. Hiramatsu. 2002. Dissemination of new methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones in the community. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:4289-4294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oliveira, D., I. Santos-Sanches, R. Mato, M. Tamayo, G. Ribeiro, D. Costa, and H. de Lencastre. 1998. Virtually all methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections in the largest Portuguese teaching hospital are caused by two internationally spread multiresistant strains: the ′Iberian' and the ′Brazilian' clones of MRSA. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 4:373-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oliveira, D. C., I. Crisostomo, I. Santos-Sanches, P. Major, C. R. Alves, M. Aires-de-Sousa, M. K. Thege, and H. de Lencastre. 2001. Comparison of DNA sequencing of the protein A gene polymorphic region with other molecular typing techniques for typing two epidemiologically diverse collections of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:574-580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oliveira, D. C., and H. de Lencastre. 2002. Multiplex PCR strategy for rapid identification of structural types and variants of the mec element in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2155-2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oliveira, D. C., A. Tomasz, and H. de Lencastre. 2001. The evolution of pandemic clones of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: identification of two ancestral genetic backgrounds and the associated mec elements. Microb. Drug Resist. 7:349-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oliveira, D. C., A. Tomasz, and H. de Lencastre. 2002. Secrets of success of a human pathogen: molecular evolution of pandemic clones of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2:180-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peacock, S. J., G. D. de Silva, A. Justice, A. Cowland, C. E. Moore, C. G. Winearls, and N. P. Day. 2002. Comparison of multilocus sequence typing and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis as tools for typing Staphylococcus aureus isolates in a microepidemiological setting. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:3764-3770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petinaki, E., V. Miriagou, L. S. Tzouvelekis, S. Pournaras, F. Hatzi, F. Kontos, M. Maniati, and A. N. Maniatis. 2001. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the hospitals of central Greece. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 18:61-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Polyzou, A., A. Slavakis, S. Pournaras, A. N. Maniatis, D. Sofianou, and A. Tsakris. 2001. Predominance of a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone susceptible to erythromycin and several other non-beta-lactam antibiotics in a Greek hospital. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48:231-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pournaras, S., A. Slavakis, A. Polyzou, D. Sofianou, A. N. Maniatis, and A. Tsakris. 2001. Nosocomial spread of an unusual methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone that is sensitive to all non-beta-lactam antibiotics, including tobramycin. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:779-781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts, R. B., A. de Lencastre, W. Eisner, E. P. Severina, B. Shopsin, B. N. Kreiswirth, A. Tomasz, et al. 1998. Molecular epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in 12 New York hospitals. J. Infect. Dis. 178:164-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sa-Leao, R., I. Santos Sanches, D. Dias, I. Peres, R. M. Barros, and H. de Lencastre. 1999. Detection of an archaic clone of Staphylococcus aureus with low-level resistance to methicillin in a pediatric hospital in Portugal and in international samples: relics of a formerly widely disseminated strain? J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1913-1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salmenlinna, S., O. Lyytikainen, and J. Vuopio-Varkila. 2002. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Finland. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:602-607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanches, I. S., M. Ramirez, H. Troni, M. Abecassis, M. Padua, A. Tomasz, and H. de Lencastre. 1995. Evidence for the geographic spread of a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone between Portugal and Spain. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:1243-1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shopsin, B., M. Gomez, S. O. Montgomery, D. H. Smith, M. Waddington, D. E. Dodge, D. A. Bost, M. Riehman, S. Naidich, and B. N. Kreiswirth. 1999. Evaluation of protein A gene polymorphic region DNA sequencing for typing of Staphylococcus aureus strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3556-3563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tassios, P. T., A. C. Vatopoulos, A. Xanthaki, E. Mainas, R. V. Goering, and N. J. Legakis. 1997. Distinct genotypic clusters of heterogeneously and homogeneously methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from a Greek hospital. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 16:170-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Teixeira, L. A., C. A. Resende, L. R. Ormonde, R. Rosenbaum, A. M. Figueiredo, H. de Lencastre, and A. Tomasz. 1995. Geographic spread of epidemic multiresistant Staphylococcus aureus clone in Brazil. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2400-2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tenover, F. C., R. D. Arbeit, R. V. Goering, P. A. Mickelsen, B. E. Murray, D. H. Persing, and B. Swaminathan. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed- field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vatopoulos, A. C., V. Kalapothaki, N. J. Legakis, et al. 1999. An electronic network for the surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in bacterial nosocomial isolates in Greece. Bull. W. H. O. 77:595-601. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]