Abstract

Objective

To compare the efficacy and tolerability of tricyclic antidepressants with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in depression in primary care.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.

Data sources

Register of the Cochrane Collaboration's depression, anxiety, and neurosis group. Reference lists of initial studies and other relevant review papers. Selected authors and experts.

Selection of studies

Studies had to meet minimum requirements on: adequacy of sample size, adequate allocation concealment, clear description of treatment, representative source of subjects, use of diagnostic criteria or clear specification of inclusion criteria, details regarding number and reasons for withdrawal by group, and outcome measures described clearly or use of validated instruments.

Main outcome measures

Standardised mean difference of final mean depression scores and relative risk of response when using the clinical global impression score. Relative risk of withdrawing from treatment at any time, and the number withdrawing due to side effects.

Results

11 studies (2951 participants) compared a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor with a tricyclic antidepressant. Efficacy between selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclics did not differ significantly (standardised weighted mean difference, fixed effects 0.07, 95% confidence interval −0.02 to 0.15; z=1.59, P<0.11). Significantly more patients receiving a tricyclic withdrew from treatment (relative risk 0.78, 95% confidence interval 0.68 to 0.90; z=3.37, P<0.0007) and withdrew specifically because of side effects (0.73, 0.60 to 0.88; z=3.24, P<0.001). Most studies included were small and supported by commercial funding. Many studies were of low methodological quality or did not present adequate data for analysis, or both, and were of short duration, typically six to eight weeks.

Conclusion

The evidence on the relative efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants in primary care is sparse and of variable quality. The study setting is likely to be an important factor in assessing the efficacy and tolerability of treatment with antidepressant drugs.

What is already known on this topic

Previous meta-analyses have included comparatively large numbers of secondary care based studies that indicate no significant differences in efficacy between selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclics

Previous meta-analyses are conflicting regarding the relative tolerability between selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclics, but do suggest a small but significant difference in favour of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Such meta-analyses show notable heterogeneity

What this study adds

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are better tolerated than tricyclics by primary care patients and may be better tolerated by primary care patients than secondary care patients

Study setting seems to be important and should be considered before licences are given to specific antidepressants

Although there are limited high quality data, available evidence shows that the most commonly prescribed classes of antidepressants in primary care (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclics) are equally effective in the short term for primary care patients, but the literature has many gaps

Introduction

Depression is the most common and costly mental health problem seen in general practice.1 Antidepressants remain the mainstay of treatment. Although most patients with clinical depression are dealt with in primary care, research findings on which treatment decisions are based have included mostly patients in secondary care. However, research indicates that patients with major depressive disorders in primary care may have a different aetiology and natural history to patients in secondary care.2,3 Concern has therefore been expressed about the relevance of secondary care studies to primary care patients.4 Previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses have included mainly secondary care studies and have compared a range of newer antidepressants with tricyclic and related antidepressants.5–9 Few reviews have focused only on comparing the two main classes of antidepressants—selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclics—and none has previously done so for patients treated in primary care alone. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of only those studies that have been conducted concerning efficacy and tolerability of antidepressants among primary care patients, comparing the most commonly used classes of antidepressants in primary care (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclics).

Methods

Inclusion criteria

We included studies if they were randomised controlled trials comparing a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor with a tricyclic antidepressant for the treatment of (predominantly adult) primary care patients with a depressive disorder. We defined primary care patients as patients who were being treated by a primary care practitioner (family practitioner, general practitioner) in a primary care setting and not by a specialist practitioner (psychiatrist) in a secondary or tertiary care setting. We excluded studies with predominantly child or elderly participants.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the efficacy of treatment comparing selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with tricyclics. As a measure of efficacy we calculated standardised mean difference of final mean depression scores and relative risk of response when using the clinical global impression score. Secondary outcomes were the number of patients withdrawing from treatment at any time and the number withdrawing because of side effects.

Identification of trials

We electronically searched the register of the depression, anxiety, and neurosis group of the Cochrane Collaboration up to April 2002. The group's controlled trials register contains randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials located by the electronic and hand searches carried out by the group's contributors. The specialised register created to help the group's members currently contains more than 10 000 records referring to completed or ongoing trials, with a quarterly accrual rate of about 500 new records (see www.iop.kcl.ac.uk/iop/ccdan/index.htm for details). Two reviewers collated and independently assessed abstracts. We searched for further trials by scrutinising the reference lists of initial studies identified and other relevant review papers. We also contacted selected authors and experts.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two reviewers independently extracted data; disagreements were resolved by discussion. Papers were translated into English by a member of staff where required. We assessed methodological quality according to the recommendations of the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook.10 We assessed studies as being of low methodological quality if they did not meet minimum requirements on each of the following elements of study design: adequacy of sample size, adequate allocation concealment, clear description of treatment, representative source of subjects, use of diagnostic criteria or clear specification of inclusion criteria, details regarding number and reasons for withdrawal by group, and outcome measures described clearly or use of validated instruments.

Statistical analysis

We used Review Manager version 4.1, a statistical software package for managing and analysing all aspects of a Cochrane Collaboration systematic review, to analyse our data. For continuous outcomes we calculated the standardised mean difference or the weighted mean difference. The standardised mean difference is the difference between two means divided by an estimate of the standard deviation within each group. When an outcome is measured in a variety of ways across studies (by using different scales) it may not be possible directly to compare or combine study results in a systematic review. By expressing the effects as a standardised value the results can be combined since they have no units. The weighted mean difference is a method used to combine measures on continuous scales, where the mean, standard deviation, and sample size in each group are known. The weight given to each study (for example, how much influence each study has on the overall results of the meta-analysis) is determined by the precision of its estimate of effect and is equal to the inverse of the variance. This method assumes that all of the trials have measured the outcome on the same scale.

For binary outcomes we calculated relative risk and the number needed to treat. We assessed heterogeneity by using the Q statistic. Any heterogeneity in the data was to be noted and cautiously explored by using previously identified characteristics of the studies, particularly assessments of methodological quality, diagnostic category, and study length. We used a fixed effects model throughout since we found no significant heterogeneity in each analysis (see figures). We looked post hoc to see what difference, if any, using a random effects model would have made. As expected confidence intervals were slightly wider but were broadly in line with the overall findings when using a fixed effects model. Where standard deviations were not provided by authors or were not available we conservatively used the highest known standard deviations from the included studies.

Results

Study inclusion and characteristics

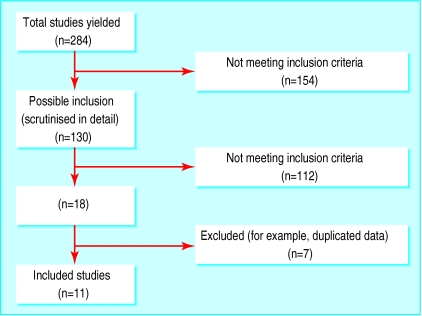

Altogether 130 of the initial 284 papers identified were potentially relevant and subjected to strict quality and eligibility assessment. Of these, we excluded 112 because they did not meet our inclusion criteria (fig1). We excluded a further seven (table 1) because they were duplicate publications, one because it compared male subjects with female subjects, one because it was primarily a study of cognitive effects and did not supply efficacy data, and one because it also included psychiatric outpatients. This left 11 studies (2954 participants) comparing a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (1607 participants) with a tricyclic antidepressant (1347 participants). Table 2 shows details of included studies.

Table 1.

Studies excluded, with reasons

| Study

|

Reason for exclusion

|

|---|---|

| Fairweather et al | Primarily study of cognitive effects of treatment with insufficient efficacy data |

| Fuglum et al | Reports details of Rosenberg 1994 study already included |

| Kornstein et al | Studied chronic and severe depression comparing male participants with female participants |

| Hunter et al | Conference abstract reporting Ravindran 1997 study already included |

| Lecrubier et al | Conference abstract reporting Ravindran 1997 study already included |

| McKendrick et al | Conference abstract referring to Thompson 2000 study already included |

| Szegedi et al | Patients included in the study came from both general practice and psychiatric outpatients |

See bmj.com for list of references to excluded studies.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the 11 studies included in the review

| Study

|

Quality*

|

Diagnosis

|

Tricyclic dose†

|

Responsible for treatment

|

Possible competing interests

|

Study period (weeks)

|

Intention to treat

|

Age range (mean age) in years

|

Proportion of female subjects

|

Study setting

|

Country

|

Drugs under comparison

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christiansen et al | High | Heterogeneous | Low | General practitioner | Yes | 8 | No | 18-65 (not known) | Not known | General practice | Denmark | Paroxetine v amitriptyline |

| Corne et al | Low | Heterogeneous | Low | General practitioner | Yes | 6 | No | 18-70 (41) | 70 | General practice | United Kingdom | Fluoxetine v dothiepin |

| Doogan et al‡ | High | Major depressive disorder | High | General practitioner | Yes | 6 | No | ≥18 (47) | 69 | General practice | United Kingdom | Sertraline v dothiepin |

| Freed et al | High | Heterogeneous | Low | General practitioner | Yes | 9 | Yes | 20-83 (48) | 65 | General practice | Australia | Paroxetine v amitriptyline |

| Malt et al§ | High | Heterogeneous | High | General practitioner | Yes | 24 | Yes | 18-79 (48) | 73 | General practice | Norway | Sertraline v mianserin |

| Moon et al 1991 | Low | Major depressive disorder | Not known | Unclear | Yes | 6 | No | 18-70 (42) | 68 | General practice | United Kingdom | Fluvoxamine v mianserin |

| Moon et al 1994 | Low | Depression and anxiety | Low | General practitioner | Yes | 6 | Yes | 19-69 (43) | 52 | General practice | United Kingdom | Sertraline v clomipramine |

| Moon et al 1996 | Low | Major depressive disorder | High | Unclear | Yes | 6 | Yes | 18-65 (45) | 71 | General practice | United Kingdom | Paroxetine v lofepramine |

| Ravindran et al | High | Depression and anxiety | Low | Unclear | Yes | 12 | Yes | 18-71 (43) | 73 | Primary care facilities | 10 different countries | Paroxetine v clomipramine |

| Rosenberg et al¶ | High | Heterogeneous | Low | General practitioner | Yes | 6 | Yes | 19-65 (47) | 69 | General practice | Denmark Sweden Norway Finland |

Citalopram v imipramine |

| Thompson et al | High | Major depressive disorder | Not known | General practitioner | Yes | 12 | Yes | 18-70 (38) | 71 | General practice | United Kingdom | Fluoxetine v dothiepin |

Quality high if adequate sample size, concealment, description of treatment, representative sample, specified inclusion, details of withdrawals, valid outcomes.

High dose defined as majority of patients treated with tricyclic antidepressants receiving at least the equivalent of 125 mg/day (140 mg lofepramine or 60 mg mianserin.

Doogan et al study has three wings (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor v tricyclic antidepressant v placebo).

Malt et al study has three wings (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor v tricyclic antidepressant v placebo).

Rosenberg et al study has two dosages of citalopram, 10-30 mg/day and 20-60 mg/day.

Most studies in the review included patients aged 18-70 (mean age 40-5). Typically about three quarters of participants were female. Most participants were white Europeans who were being treated by their general practitioner. Six of the studies took place in the United Kingdom; two in Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Finland; one in Norway; and one in Australia. One study included 121 centres from 10 different countries, including Canada, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and South Africa.

Four studies did not meet the minimum quality criteria on at least one of the key components of methodological quality. Two studies had inadequate allocation concealment; one study had inadequate allocation concealment and withdrawal details; and one study had a small sample size and inadequate details on withdrawal. Funnel plots indicated no obvious publication or related bias. All included studies were either supported by commercial funding or included at least one author who was employed by a pharmaceutical company, or both.

Effectiveness

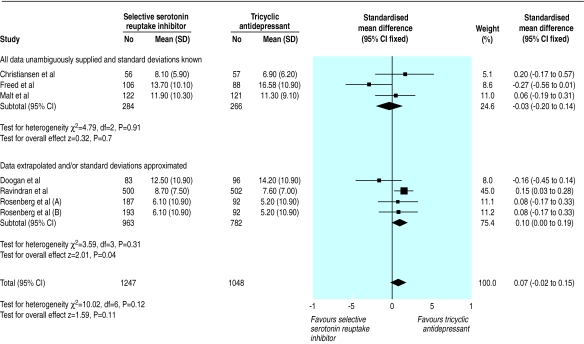

Final mean continuous depression scale scores

Six studies contributed to the analysis; they included 2295 patients of whom 1247 received a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and 1048 a tricyclic antidepressant. Only three studies provided data in an unambiguous format and provided standard deviations. Overall we made seven comparisons since one study had two groups of patients receiving a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor at different dosages.

The standardised weighted mean difference when using fixed effects was 0.07 (95% confidence interval −0.02 to 0.15), which is a slight but non-significant effect in favour of tricyclic antidepressants (fig 2). Figure 2 shows that if only the three studies that provide unambiguous data and standard deviations are included the effect that favours the tricyclics disappears (−0.03, −0.20 to 0.14). If three studies of low quality are also included in the overall analysis (thus 10 comparisons in all) the difference in favour of tricyclics is similar (0.05, −0.02 to 0.15).

Figure 2.

Effectiveness of treatments when using standardised continuous outcome measures. References to studies can be found on bmj.com

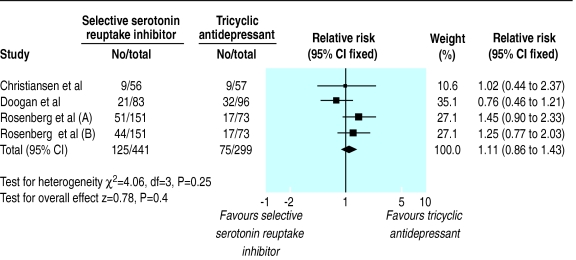

Clinical global impression (improvement)

Three studies contributed four comparisons for this analysis; they included 740 patients of whom 441 received a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and 299 a tricyclic antidepressant. The difference between the two treatments does not seem to reach statistical significance (relative risk 1.11, 0.86 to 1.43; fig 3). If the four low quality studies are included in the analysis there is still no suggestion of a difference (1.05, 0.87 to 1.27).

Figure 3.

Effectiveness of treatment when using clinical global impression (improvement) scale. References to studies can be found on bmj.com

Tolerability

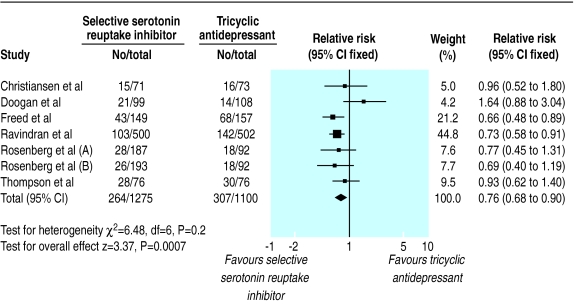

Number of patients withdrawing from treatment for any reason

Six studies contributed seven comparisons for this analysis. These included 2375 patients of whom 1275 received a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and 1100 a tricyclic antidepressant (fig 4). Of patients receiving a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, 20.7% (264) withdrew from treatment, compared with 27.9% (307) of patients treated with a tricyclic. Pooled estimates significantly favoured the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (relative risk 0.78, 0.68 to 0.90, P=0.0007). The number needed to treat was 14 (95% confidence interval 10 to 27). The overall results remain broadly similar if the four low quality studies are also included in the analysis (0.81, 0.70 to 0.92).

Figure 4.

Number of patients withdrawing from treatment for any reason

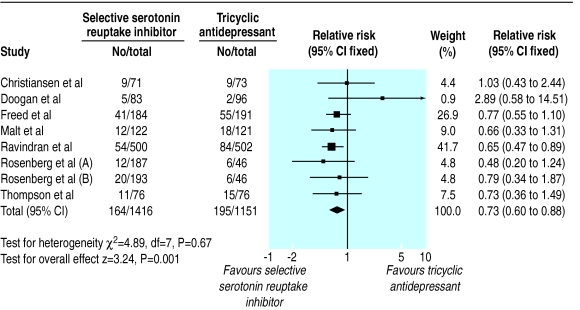

Number of patients withdrawing from treatment because of drug related adverse events

Seven studies with eight comparisons provided data for the analysis, including 2567 patients of whom 1416 received a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and 1151 a tricyclic antidepressant (fig 5). Significantly fewer (11.6%; 9.9% to 13.3%) patients (n=164) receiving a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor withdrew due to drug related adverse events than patients (n=196) treated with a tricyclic (17.0% (14.8% to 19.1%) (relative risk 0.73, 0.60 to 0.88; NNT 18, 12 to 33)). Results remained almost identical if the four low quality studies were included in the overall analysis (0.73, 0.61 to 0.88).

Figure 5.

Number of patients withdrawing from treatment due to side effects

Discussion

We found significantly lower rates of dropout for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (20.7%, 18.5% to 22.9%) than for tricyclics (27.9%, 25.3% to 30.5%)). Previous reviews have also indicated that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are generally more tolerable than tricyclics, but evidence has been conflicting. One review found no difference in the dropout rate between selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (32.3%) and tricyclics (33.2%),8 whereas another found a lower dropout rate for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (30.8%, 29.2% to 32.4%) compared with tricyclics (33.4%, 31.7% to 35.1%).9 Our results show lower dropout rates than those reported in other, non-primary care based reviews—10% less for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and 5.5% less for tricyclics.

Dropout rates are an imprecise index of tolerability, however, since patients may stop taking medication for many reasons. A more precise index of tolerability may be withdrawal from treatment because of problems with side effects. It should be noted, however, that patients may still find antidepressants intolerable, although they may continue to adhere to treatment. Few previous reviews have included an analysis of withdrawal due to side effects; one has found that 15.4% of patients treated with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and 18.8% of patients receiving a tricyclic antidepressant withdrew from treatment for such reasons.8 By comparison, we found very much lower rates of withdrawal when selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors were used (11.6%, 9.9% to 13.3%) and only slightly lower rates when tricyclics were used (17.0%, 14.8% to 19.1%). This finding shows that primary care patients are not only more likely to continue taking a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor than a tricyclic antidepressant but that they may also be more likely to continue with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors than are secondary care patients.

Lower rates of withdrawal from treatment among participants taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors than among those taking tricyclics may be due to the inclusion of studies that examine older tricyclics (amitriptyline and imipramine), which are likely to have a greater propensity to cause problematic side effects.11 When these older agents were excluded previously, no differences in tolerability between the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and newer tricyclics were found.11 In our review, three of the 11 studies included used an older tricyclic drug. When these three studies were excluded, the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors remained significantly more tolerable (0.69, 0.53 to 0.90, P=0.006). It is possible, however, that this was because relatively high daily doses of tricyclics were used. A recent review comparing low doses of tricyclic antidepressants with standard (higher) doses found that participants receiving low doses were 55% less likely to drop out from treatment due to side effects.12 But no study in our review that included amitriptyline or imipramine used a mean dose at or above the minimum recommended level of 125 mg per day. Furthermore, only three of the 11 studies included in our review resulted in patients receiving minimum recommended daily doses or higher doses of a tricyclic.

Our results imply that, in the short term, no significant differences exist in efficacy between selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclics in patients in primary care. Previous reviews, which included mainly secondary care patients, have shown similar results.5–9 Unlike previous reviewers who focused mainly on secondary care, however, we did not detect any significant heterogeneity in the data. This may indicate that study setting is important since reviews that include patients from different settings usually find heterogeneity.7 Heterogeneity may have many explanations other than study setting, not least the inclusion of patients with a range of different diagnostic categories of illness. The inclusion criteria for presentation of illness in primary care based studies included in the review were generally very similar, but we used three main categories for inclusion: major depressive disorder of moderate to severe severity, mixed anxiety and depression, and a mixture of different depressive presentations. Most studies in the review included a range of patients who had major or minor presentations and excluded patients whose illness was assessed as mild or severe. Thus even though the overall sample included in our review comprised several different diagnostic groups, no heterogeneity was present.

None of the studies included in our review specifically examined minor depressive disorder, mild presentations of a major depressive disorder, or dysthymia. This is important because research indicates differences in outcome depending on diagnostic category. A prospective study of the outcome of depressive disorders in primary care, for example, found that good outcome was predicted by mild depression at initial assessment.13 Evidence accumulated so far regarding the efficacy of antidepressants seems to be more robust for the treatment of major depressive disorders but is less well established for minor presentations.14 Findings from our review, which show that there are no primary care based studies focused on such presentations, further highlight a need to conduct studies that include only minor or milder presentations.

We found only 11 studies based in primary care that met our inclusion criteria and provided evidence for the comparative efficacy and tolerability of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with tricyclics. This compares with considerably larger numbers of studies conducted with patients from all settings (123 trials in one review5 and 36 trials in a review including only United States based trials6). Given that we know that most depressed patients are treated in primary care only, we expected that a larger proportion of trials including only primary care patients would have been conducted. Furthermore, since differences in tolerability of medicines may exist between patients treated in different settings, it may be appropriate for bodies that grant licences for drugs to ensure that studies have been carried out in appropriate settings before granting specific antidepressants their licence.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Number of studies yielded by search strategy. References to studies can be found on bmj.com

Acknowledgments

The study group thanks Rachael Churchill, coordinating editor, for early comments on the direction of the study and Hugh Mcguire, trials search coordinator, for performing the search strategy (both from the Cochrane Collaboration Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group); Erika Glenday for translation from German into English; Victoria Andersen for translation of Norwegian and Danish into English; Pauline McCann, senior library assistant, and colleagues in the Medical Library Ninewells Hospital for help in retrieving the primary literature; and the Chief Scientist Office (Scotland) Health Services Research Committee for providing the funding.

Footnotes

Funding: Chief Scientist Office (Scotland) grant number CZG/3/2/101.

Competing interests: SM has been reimbursed by GlaxoSmithKline for attending and speaking at conferences. SM and BW have received an unconditional educational grant from Eli-Lilly and are also involved in research unconditionally funded by GlaxoSmithKline. ICR has received research funding from Wyeth, Organon, and GlaxoSmithKline, and consultancy fees from Janssen, Organon and Eli-Lilly. FS is a member of the Medicines Monitoring Unit (MEMO) executive in the University of Dundee, which accepts unrestricted educational grants from pharmaceutical companies.

References to included and excluded studies appear on bmj.com

References

- 1.Katon W, Schulberg H. Epidemiology of depression in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1992;14:237–247. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(92)90094-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suh T, Gallo JJ. The management of depression among general medical service providers. Psychol Med. 1999;27:1051–1063. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arya R. The management of depression in primary health care. Curr Opin. 1999;12:103–107. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gill D. Prescribing antidepressants in general practice. Systematic review of all pertinent trials is required to establish guidelines. BMJ. 1997;314:826–827. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams JW, Jr, Mulrow CD, Chiquette E, Noel PH, Aguilar C, Cornell J. A systematic review of newer pharmacotherapies for depression in adults: evidence report summary. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:743–756. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-9-200005020-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steffens DC, Krishnan KR, Helms MJ. Are SSRIs better than TCAs? Comparison of SSRIs and TCAs: a meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 1997;6:10–18. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6394(1997)6:1<10::aid-da2>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.North of England Evidence Based Guideline Development Project. The choice of antidepressants for depression in primary care: evidence based clinical practice guideline. Newcastle upon Tyne: Centre for Health Services Research, University of Newcastle UK; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song F, Freemantle N, Sheldon TA, House A, Watson P, Long A, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: meta-analysis of efficacy and acceptability. BMJ. 1993;306:683–687. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6879.683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson IM, Tomenson BM. Treatment discontinuation with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors compared with tricyclic antidepressants: a meta-analysis. BMJ. 1995;310:1433–1438. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6992.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mulrow CD, Oxman AD. Cochrane Library. Issue 4. Oxford: Update Software; 1997. Cochrane collaboration handbook. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hotopf M, Hardy R, Lewis G. Discontinuation rates of SSRIs and tricyclic antidepressants: a meta-analysis and investigation of heterogeneity. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:120–127. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.2.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furukawa TA, McGuire H, Barbui C. Meta-analysis of effects and side effects of low dosage tricyclic antidepressants in depression: systematic review. BMJ. 2002;325:991–995. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7371.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ronalds C, Creed F, Stone K, Webb S, Tomenson B. Outcome of anxiety and depressive disorders in primary care. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:427–433. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.5.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katon W, von Korff M, Lin E, Walker E, Simon G, Bush T, et al. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines: the impact of depression in primary care. JAMA. 1995;273:1026–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.