Abstract

This study describes the optimization of PCR parameters and testing of a wide number of microbial species to establish a highly specific and sensitive PCR-based method of detection of a newly emerged pandemic Vibrio parahaemolyticus O3:K6 strain in pure cultures and seeded waters from the Gulf of Mexico (gulf water). The selected open reading frame 8 (ORF8) DNA-specific oligonucleotide primers tested were found to specifically amplify all 35 pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 pandemic isolates, whereas these primers were not found to detectably amplify two strains of V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 that were isolated prior to the 1996 outbreaks, 122 non-O3:K6 strains of V. parahaemolyticus, 198 non-V. parahaemolyticus spp., or 16 non-Vibrio bacterial spp. The minimum level of detection by the PCR method was 1 pg of purified genomic DNA or 102 ORF8-positive V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 cells in 100 ml of water. The effectiveness of this method for the detection of ORF8-positive isolates in environmental samples was tested in gulf water seeded with 10-fold serial dilutions of this pathogen. A detection level of 103 cells per 100 ml of gulf water was achieved. Also, the applicability of this methodology was tested by the detection of this pathogen in gulf water incubated at various temperatures for 28 days. This PCR approach can potentially be used to monitor with high specificity and well within the required range of sensitivity the occurrence and distribution of this newly emerged pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 strain in coastal, marine, and ship ballast waters. Early detection of V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 will help increase seafood safety and decrease the risk of infectious outbreaks caused by this pathogen.

Vibrio parahaemolyticus is a natural inhabitant of coastal waters worldwide (6, 25). This organism is a halophilic, gram-negative bacterium that causes gastroenteritis in humans. Infection results from the consumption of contaminated seafood, particularly raw shellfish. A significant increase in the number of cases of V. parahaemolyticus infections was reported in 1996. A unique clone of V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 is responsible for many of the recent V. parahaemolyticus outbreaks, including epidemics in India, Russia, Southeast Asia, Japan, and North America (9, 13, 17, 23). Strains of the O3:K6 serovar emerged in Calcutta, India, in 1996 and have accounted for 50 to 80% of V. parahaemolyticus infections annually since then. The same serovar was isolated from patients in various Southeast Asian countries, and it was found that the O3:K6 strains isolated since 1996 are all derived from a single clone (20). In 1997, an outbreak caused by V. parahaemolyticus occurred in the Pacific Northwest, resulting in one death and 209 illnesses. Each of the infected persons had consumed raw oysters (8). V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 was involved in outbreaks from contaminated oysters harvested from Oyster Bay, N.Y., and Galveston Bay, Tex., in 1998 (8, 12). The V. parahaemolyticus outbreak in Galveston Bay was the largest reported in the United States (416 persons), and all clinical isolates were the O3:K6 serotype (12).

It was determined that a filamentous phage, f237, is specifically and exclusively associated with O3:K6 serovar strains isolated since 1996 (19). This phage has 10 open reading frames (ORFs), including a unique open reading frame, ORF8, which shows no homology to known DNA sequences. Vibrio cholerae has a similar filamentous phage, CTX, which carries the cholera enterotoxin genes ctxA and ctxB (15). In V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6, the f237 phage has ORF8 in place of ctxAB (26). Therefore, it is suggested that ORF8 may play a role in the virulence of the strains that possess it because of the increased infection rates in these strains (19, 20, 22).

The “new” V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 pathogenic strain with the f237 phage was first isolated in Calcutta, India. Like the spread of the epidemic strain of V. cholerae O1 in 1991 to coastal waters along the Gulf of Mexico (18), it is probable that the spread of the pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 strain occurred via ship ballast water, which is believed to be the leading cause for the spread of nonindigenous organisms in the marine environment. Therefore, it is necessary and desirable to be able to detect the pathogenic strains of V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 in the environment, particularly in marine water, to monitor its presence. Detection of V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 in waters where shellfish are harvested can help prevent infections resulting from ingestion and thus improve the safety of shellfish. This detection will benefit the shellfish industry and will ensure consumer confidence in the consumption of seafood.

To prevent infections, it is necessary to detect this pathogen rapidly and reliably. Conventional biochemical methods for the detection of V. parahaemolyticus are time-consuming, requiring several days to acquire confirmatory results (14, 16). Several gene-based methodologies that target species and virulence gene segments, like PCR (11, 24; G. Blackstone, Abstr. 101st Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 2001, abstr. Q-454, p. 676, 2001), colorimetric DNA-DNA hybridization (18), and multiplex PCR (4), have been developed. However, these methodologies are not specific for the detection of newly emerged pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 strains. In this study, we describe the selection of ORF8 template-specific oligonucleotide primers and the optimization of PCR amplification to establish a qualitative PCR with high specificity and sensitivity for the detection of these newly emerged pandemic isolates of V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 in pure cultures and in seeded gulf waters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and microbiological media.

All V. parahaemolyticus bacteria used in this study, including O3:K6 isolates and non-V. parahaemolyticus strains, are listed in Table 1. V. parahaemolyticus was cultured in T1N1 broth medium (10% tryptone, 1% NaCl) (1) or on T1N3 agar plates (10% tryptone, 3% NaCl) (1) at 35°C overnight. All other strains were grown and maintained as follows: V. cholerae was grown on Luria broth (LB) (5 g of yeast extract, 10 g of tryptone, 10 g of NaCl) agar or broth at 37°C overnight; Vibrio hollisae, Vibrio fluvialis, Vibrio metschnikovii, and Vibrio mimicus were grown on one-half-strength marine broth or agar (Difco) at 30°C overnight; V. vulnificus was grown on marine agar or broth at 35°C overnight; and all other non-Vibrio species were grown on LB or nutrient agar (NA) at their optimum temperatures (1).

TABLE 1.

PCR results for ORF8 using primers F-O3MM824 and R-O3MM1192

| Strain (origin) | ORF8a |

|---|---|

| Vibrio parahaemolyticus O3:K6 | |

| AQ-4037 (pre-1996) | − |

| U 5474 (pre-1996) | − |

| 02006636 (Conn.) | + |

| 02006637 (Conn.) | + |

| TX-2029 (Tex.) | + |

| TX-2030 (Tex.) | + |

| TX-2051 (Tex.) | + |

| TX-2062 (Tex.) | + |

| TX-2071 (Tex.) | + |

| TX-2072 (Tex.) | + |

| TX-2103 (Tex.) | + |

| TX-2107 (Tex.) | + |

| TX-2108 (Tex.) | + |

| TX-2116 (Tex.) | + |

| BAC 98-03255 (N.Y.) | + |

| BAC 98-4092 (N.Y.) | + |

| BAC 98-4093 (N.Y.) | + |

| BAC 98-4095 (N.Y.) | + |

| AN-8373 (India) | + |

| VP86 (India) | + |

| VP96 (India) | + |

| VP138 (India) | + |

| VP155 (India) | + |

| VP199 (India) | + |

| VP208 (India) | + |

| FIHES98V1-32-4 (Japan) | + |

| JYK-VP6 (Japan) | + |

| VP2 (Korea) | + |

| 97LVP2 (Laos) | + |

| KX-V226 (Singapore) | + |

| KX-V225 (Thailand) | + |

| VP47 (Thailand) | + |

| BAC 98-03372 (unknown) | + |

| BAC 98-03374 (unknown) | + |

| BAC 98-3064 (unknown) | + |

| BAC 98-3524 (unknown) | + |

| BAC 98-3675 (unknown) | + |

| Non-O3:K6 | |

| AN-16000 O1:KUT | + |

| AN-5034 O4:K68 | + |

| BAC 98-3547 O4:K55 | − |

| CONN-02006628 O6:K18 | − |

| 10290 | − |

| 10291 | − |

| 10292 | − |

| 10293 | − |

| 10294 | − |

| 10295 | − |

| 10296 | − |

| 10297 | − |

| 41977 | − |

| 47583 | − |

| 47977 | − |

| 47978 | − |

| 48057 | − |

| 48215 | − |

| 48256 | − |

| 48262 | − |

| 48291 | − |

| 48432 | − |

| 553-14 | − |

| 8657 | − |

| 8659 | − |

| 8700 | − |

| 901128 | − |

| 9401078 | − |

| 9401392 | − |

| 94-10199 | − |

| 94-10201 | − |

| 94-10203 | − |

| ATCC 17802 | − |

| KCHD613 | − |

| SAK5 | − |

| SAK11 | − |

| T3979 | − |

| T3980 | − |

| 13A15J | − |

| 3VOC | − |

| 30V10A | − |

| 8G5 | − |

| 8338335 | − |

| 832850 | − |

| 855329-2 | − |

| 9200713 | − |

| 96736341 | − |

| 97-021 | − |

| 97-027 | − |

| 97-029 | − |

| 97-046a | − |

| 97-046b | − |

| 97-049a | − |

| 97-049b | − |

| 97-056 | − |

| 97-107 | − |

| AOC3 | − |

| AOC7 | − |

| F113A | − |

| M350A | − |

| WR5 | − |

| 35VOA | − |

| DAL-1094 | − |

| OR152 | − |

| VP43-1A | − |

| VP53 | − |

| VP89-1B | − |

| WR2 | − |

| B8 | − |

| JJ2J1C | − |

| JJ41B2 | − |

| JJ51A | − |

| MM3 | − |

| 14D1 | − |

| 14D10 | − |

| NY477 | − |

| 13A15K | − |

| 1904653 | − |

| 35VOA | − |

| 48275 | − |

| 49275 | − |

| 8332924 | − |

| 89 | − |

| 96736341 | − |

| ATCC 27519 | − |

| ATCC 33844 | − |

| ATCC 33845 | − |

| VPN7 | − |

| CT 6628 | − |

| DAL 1094 | − |

| TX 2046 | − |

| Cliff-MA | − |

| Vp oys | − |

| 520 | − |

| 1163 | − |

| 2655 | − |

| 4037 | − |

| 116194 | − |

| CPA11 091399 | − |

| CPB12 091399 | − |

| 295-3 | − |

| 1029 | − |

| DIA6 031699 | − |

| DIB11 031699 | − |

| DID12 031699 | − |

| DIB7 031699 | − |

| DIF8 031699 | − |

| DIE12 052499 | − |

| DIH8 060899 | − |

| DIA9 070799 | − |

| CPA7 081699 | − |

| DIA2 122799 | − |

| DIA11 011100 | − |

| DIA8 012500 | − |

| DIA-6-1 020800 | − |

| DIA-6-1 031400 | − |

| DIE3 031400 | − |

| DIB-1 052300 | − |

| DIB-5 052300 | − |

| DIB-1 060600 | − |

| CPB-5 060600 | − |

| DIB-1 062000 | − |

| CPA-6 072500 | − |

| Vibrio cholerae | |

| 0138 | − |

| 0145B | − |

| 154 (O1) | − |

| 89A4555 | − |

| ATCC | − |

| ATCC 25870 569B | − |

| 17-17 | − |

| C153 | − |

| 20-21 | − |

| 24-21 | − |

| 25-16 | − |

| 25-37 | − |

| 25-62 | − |

| 25-72 | − |

| 40-14 | − |

| 44-62 | − |

| 72-24 | − |

| 95-17 | − |

| 133-29 | − |

| 135-17 | − |

| 140-16 | − |

| 167-19 | − |

| Vibrio hollisae | |

| 1960A | − |

| 89A4206 | − |

| CFSAN 89A1960 | − |

| CFSAN 89A4206 | − |

| DAL 2039 | − |

| DAL 8391 | − |

| DAL 8393 | − |

| DAL 8395 | − |

| SPRC 8397 | − |

| Vibrio vulnificus | |

| 304 | − |

| A9 | − |

| CDC9062-96 | − |

| CDC9063-96 | − |

| CDC9064-96 | − |

| CDC9067-96 | − |

| CDC9341-95 | − |

| CDC9342-95 | − |

| CDC9343-95 | − |

| CDC9344-95 | − |

| CDC9345-95 | − |

| CDC9346-95 | − |

| CDC9347-95 | − |

| CVD2 | − |

| CVD7 | − |

| J-7 | − |

| CVD11 | − |

| MO6-24 | − |

| SEA 10115 | − |

| SPRC 10111 | − |

| SPRC 1275 | − |

| SPRC 10271 | − |

| SPRC 10273 | − |

| SPRC 10277 | − |

| VBNO | − |

| Vibrio fluvialis | |

| 11176 | − |

| 11961 | − |

| 1959-82 | − |

| 2386 | − |

| 2926 | − |

| 3282 | − |

| 4267 | − |

| 5125 | − |

| 5137 | − |

| 7214 | − |

| DAL 116 | − |

| DAL 197 | − |

| DAL 506 | − |

| DAL 1678 | − |

| DAL 1825 | − |

| GCSL 358-2 | − |

| Vibrio metschnikovii | |

| 10917 | − |

| 11572 | − |

| 2068 | − |

| 2360A | − |

| 2362 | − |

| 2375 | − |

| 2376 | − |

| 2468 | − |

| 2476 | − |

| 2477 | − |

| 2480 | − |

| 9798 | − |

| ATCC 7708 | − |

| Vibrio alginolyticus | |

| ATCC 17749 | − |

| Z106 | − |

| Vibrio campbellii | |

| ATCC 25920 | − |

| Vibrio mimicus | |

| 1531 | − |

| 196 | − |

| 2227 | − |

| 291 | − |

| 59 | − |

| 667 | − |

| 709-P | − |

| 85 | − |

| ATCC 33053 | − |

| C-158 | − |

| Non-Vibrio strains | |

| Aeromonas salmonicida ATCC 14174 | − |

| Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6051 | − |

| Enterobacter aerogenes ATCC 13045 | − |

| Escherichia coli ATCC 15224 | − |

| Escherichia coli O157:H7 ATCC 35150 | − |

| Hafnia alvei ATCC 29926 | − |

| Klebsiella oxytoca ATCC 12833 | − |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 13883 | − |

| Pseudomonas putida mt-2 | − |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens ATCC 13525 | − |

| Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium ATCC 19585 | − |

| Serratia marcescens ATCC 13880 | − |

| Shigella sonnei ATCC 29930 | − |

| Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 12600 | − |

| Streptococcus lactis ATCC 8043 | − |

| Streptococcus pyogenes ATCC 14289 | − |

ORF8 was found to be present (+) or absent (−).

DNA purification for PCR optimization.

Total genomic DNA from all V. parahaemolyticus and other bacterial strains listed in Table 1 was purified as described by Ausubel et al. (3). Briefly, cells were suspended in 567 μl of TE (10 mM Tris · Cl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA) buffer with 30 μl of 10% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate and 3 μl of 20-mg/μl proteinase K (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) and were lysed for 1 h at 37°C. Next, 100 μl of 5 M NaCl and 80 μl of cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB)-NaCl were added and the solution was incubated for 10 min at 65°C. DNA was purified by extraction with chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1) followed by extraction with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1). DNA was then precipitated with isopropanol, centrifuged for 5 min at 10,000 × g, washed with cold 70% (vol/vol) ethanol, and dried in a DNA SpeedVac (Savant). The dried DNA was resuspended in 25 μl of TE buffer, and the DNA concentration was measured with a Lambda II spectrophotometer (Perkin-Elmer, Shelton, Conn.) at a wavelength of 260 nm.

Selection of target and oligonucleotide primer sequences.

A segment of the ORF8 DNA sequence (GenBank accession no. AP000581 and NC002473) was used as the PCR target for specific detection of the newly emerged pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 isolates. Potential primer sequences were analyzed for specificity by comparison with known gene sequences by using the National Center for Biotechnology Information GenBank database with the BLAST search program and by using the nucleotide sequence analysis developed in this study. An oligonucleotide primer set, F-O3MM823 and R-O3MM1192 (Table 2), located between bp 823 and 1192 of the ORF8 DNA segment was used in each PCR to test the specificity of detection of all the V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 isolates and other bacterial strains used in this study. Two other oligonucleotide primers, F-O3MM80 and R-O3MM1193, located between bp 80 and 1193 of the ORF8 DNA segment were selected (Table 2) for PCR amplification of a segment of ORF8 for the purposes of cloning and DNA sequence analysis. The melting temperatures (Tms) of all the primers were determined by the formula Tm (degrees Celsius) = 2(A + T) + 4(G + C) (21). All primers were custom synthesized by Integrated DNA Technology, Inc., Coralville, Iowa.

TABLE 2.

Description of the PCR primer sequences, location lengths, Tms, and amplicon sizes used in this study

| Target | Primer | Sequence | Positions within ORF8 DNA (bp) | Length (nta) | Tm (°C) | Amplicon size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORF8 | F-O3MM80 | 5′-GTTCGCATACAGTTGAGG-3′ | 80-97 | 18 | 54 | 1,114 |

| R-O3MM1193 | 5′-GCTAACGCATTGTCCCTTTGTA-3′ | 1172-1193 | 22 | 64 | ||

| ORF8 | F-O3MM824 | 5′-AGGACGCAGTTACGCTTGATG-3′ | 824-844 | 21 | 64 | 369 |

| R-O3MM1192 | 5′-CTAACGCATTGTCCCTTTGTAG-3′ | 1171-1192 | 22 | 64 |

nt, nucleotides.

Optimization of PCR and specificity of oligonucleotide primers.

Purified genomic DNA from V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 TX-2062 was used for the optimization of PCR amplification. In a PCR, a 200 μM concentration of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Sigma), a 1 μM concentration of each of the oligonucleotide primers, 1.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega), 1 μg of template DNA, and 1× PCR buffer were used. The optimal PCR buffer was determined by using buffers E (7 mM MgCl2 [pH 9.0], 300 mM Tris · Cl, 75 mM ammonium sulfate), F (10 mM MgCl2 [pH 9.0], 300 mM Tris · Cl, 75 mM ammonium sulfate), and G (12.5 mM MgCl2 [pH 9.0], 300 mM Tris · Cl, 75 mM ammonium sulfate) from a PCR Optimizer kit (Invitrogen, Inc., Carlsbad, Calif.). All PCR amplifications were performed in a DNA thermal cycler (model 2400; Perkin-Elmer) with the following PCR cycling parameters: initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of amplification. Each amplification cycle consisted of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, primer annealing at 56, 60, or 64°C for 30 s, and primer extension at 72°C for 30 s. After amplification, a final extension step was done at 72°C for 5 min.

Specificity of detection.

The specificities of the oligonucleotide primers (Table 2) and the target DNA segment, ORF8, for the detection of pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 isolates were tested by PCR amplification of the purified genomic DNA of all the strains listed in Table 1 by using the optimum PCR conditions and cycling parameters described above.

Sensitivity of detection.

Purified genomic DNA (1 μg) from V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 TX-2062 was 10-fold serially diluted in sterile distilled water up to 0.01 fg. PCR amplification was performed under the determined optimal conditions at an annealing temperature of 60°C and other parameters as described above. The experiment was performed in triplicate to determine the consistency of the level of detection by this method.

Detection of V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 in seeded gulf water.

V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 TX-2062 was grown overnight in T1N1 broth at 37°C, inoculated into fresh T1N1 broth, and grown at 37°C to an optical density at 450 nm (OD450) of approximately 0.4, which corresponds to approximately 3 × 106 cells/ml as determined by viable plate counting. Cells were 10-fold serially diluted to extinction in 100 ml of autoclaved (121°C for 15 min) water from the Gulf of Mexico (gulf water). The gulf water was collected from Dauphin Island, Ala., and the salinity was determined to be 28 ppt by using a refractometer (Reichert Scientific Instruments, Buffalo, N.Y.). To determine any effects of the gulf water that were inhibitory to the PCR, cells were 10-fold serially diluted in 100 ml of sterile MilliQ water and used as a control. The cells were collected by centrifugation at 21,000 × g for 30 min at 5°C. The supernatant was carefully discarded, and the cells were resuspended in 50 μl of sterile MilliQ water. The samples were boiled with 0.05 mg of Chelex 100 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) at 100°C for 10 min. For each 50 μl of PCR mixture, 3 μl of the boiled sample was used as a source of the template DNA.

For comparison, an UltraClean soil DNA kit (MO BIO Laboratories, Carlsbad, Calif.) and a FastDNA SPIN kit (Bio 101, La Jolla, Calif.) were used to process samples for PCR amplification. These kits are designed to isolate PCR-ready DNA from soil and sediment. Cells were grown, serially diluted in autoclaved (121°C for 15 min) gulf water, and centrifuged as described above. The samples were then resuspended in 50 μl of sterile MilliQ water and processed as instructed in each of the respective kits. Following extraction, the DNA was resuspended in 50 μl of TE buffer with Tris · Cl at pH 7.2 and stored at 4°C until used for PCR amplification. For both kits, 3 μl of a sample was used for amplification with a 50-μl PCR mixture. To determine the consistency of the level of detection, all experiments were conducted in triplicate.

Detection of amplified DNA.

All PCR-amplified DNAs were separated at a constant voltage of 5 V/cm in 1% (wt/vol) SeaKem agarose (FMC Bioproducts, Inc., Rockland, Maine) with 1× TAE (per liter, 40 mM Tris · Cl [pH 8.0], 1.18 ml of acetic acid, 2 mM Na2-EDTA) (3). The separated DNA in the gel was stained with 2 × 10−4 μg of ethidium bromide per ml and visualized on a FotoPrep I (Fotodyne, Inc.) UV transilluminator. The amplified DNA bands were photographed with Polaroid type 55 film.

Cloning and sequencing of V. parahaemolyticus strains.

Purified genomic DNA (1 μg) from V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 strains TX-2062, BAC 98-03372, 0206636, and VP2 was subjected to PCR amplification using primers F-O3MM80 and R-O3MM1193. The amplified product was cloned on the PCR 4.0 plasmid vector by using a Topo TA cloning instrument (Invitrogen). Positive transformants were selected on LB agar plates supplemented with the antibiotic kanamycin (50 μg/μl), X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside), and IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) (Sigma) as described in the kit instructions. DNA was extracted and purified by using a QIAprep Spin Miniprep kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, Calif.). Purified DNA was subsequently treated with EcoRI restriction endonuclease (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) and visualized in a 1% (wt/vol) agarose gel (FMC Bioproducts) for analysis of the cloned fragments. Three clones from each strain with the DNA inserts of expected molecular weights were subjected to nucleotide sequence analysis by using the Sanger dideoxy chain termination reaction and T7 and T3 oligonucleotide primers (Invitrogen) in an ABI Prism automated DNA sequencer (Perkin-Elmer).

Detection of V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 cultures after extended incubation at various temperatures.

The V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 TX-2062 strain was grown in autoclaved (121°C for 15 min) gulf water (28 ppt salinity, 300 ml) supplemented with 0.2% peptone (wt/vol) (Difco) until the optical density at 450 nm reached 0.2, and the number of viable cells was determined by plating the culture onto T1N3 agar plates. Equal volumes of the culture were then distributed in three 250-ml sterile flasks and transferred at 4 and 15°C and at room temperature (21 ± 1°C). Then 1 ml of the culture was removed from each flask into a microcentrifuge tube and centrifuged at 10,000 × g, and the cell pellet was treated with Chelex 100 (Bio-Rad) to release the DNA. An aliquot (3 μl) of the DNA was subjected to PCR amplification using the primers and reaction parameters described in the previous section. Similarly, after 7, 21, and 28 days of incubation at the respective temperatures, 1 ml of the culture from each flask was removed and subjected to PCR amplification. The PCR-amplified DNA was separated and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Also, at each time period, 1 ml of the culture from each of the flasks kept at the respective temperature was 10-fold serially diluted in T1N1 medium and plated onto T1N3 agar plates to determine viable plate counts. This experiment was performed in triplicate, and appropriate PCR-positive and -negative controls were included.

RESULTS

Specificities of oligonucleotide primers.

The oligonucleotide primers, F-O3MM823 and R-O3MM1192, amplified the targeted ORF8 DNA segments of all 35 newly emerged V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 isolates. Comparisons of the 1,114-bp DNA segments of the ORF8 sequences among V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 strains BAC 98-03372, 0206636, TX-2062, and VP2 revealed identical nucleotide sequences. However, comparisons of the nucleotide sequences from these strains with the GenBank ORF8 sequence from V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 revealed differences in the nucleotide sequences at nucleotide positions 409 (G→T), 487 (G→C), 526 (T→C), 535 (G→T), 552 (G→A), 565 (T→C), and 680 (G→C). The nucleotide sequence of the V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 BAC 98-03372 strain is available in the GenBank database (accession no. AY196694). It is not clear whether these single nucleotide changes would affect the virulence of these strains. However, for this study, the nucleotide sequences within the F-O3MM823 and R-O3MM1192 primer segments were consistent in all of these strains, which led us to select these oligonucleotide primers for PCR detection of V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 strains (Tables 1 and 3). None of the non-O3:K6 Vibrio strains or non-Vibrio strains tested in this study exhibited any PCR amplification except for the AN-16000 O1:K untypeable strain (KUT) and AN-5034 O4:K68.

TABLE 3.

Summary of PCR results for ORF8

| Bacterial species | No. of strains tested | No. of strains positive for ORF8 |

|---|---|---|

| V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 (1996 and after isolates) | 35 | 35 |

| V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 (prior to 1996 isolates) | 2 | 0 |

| V. parahaemolyticus (non-O3:K6 strains) | 123 | 2a |

| V. cholerae | 22 | 0 |

| V. hollisae | 9 | 0 |

| V. vulnificus | 25 | 0 |

| V. fluvialis | 16 | 0 |

| V. metschnikovii | 13 | 0 |

| V. mimicus | 10 | 0 |

| V. alginolyticus | 2 | 0 |

| V. campbellii | 1 | 0 |

| Non-Vibrio species | 16 | 0 |

The two strains that tested positive were V. parahaemolyticus O1:KUT and V. parahaemolyticus O4:K68, which are known to have ORF8.

Optimization of PCR and cycling parameters.

PCR amplification was determined to be optimal with buffer F from the PCR Optimizer kit (Invitrogen) at an annealing temperature of 60°C. Decreased intensities of the amplified product in an agarose gel were observed with buffers E and G. At an annealing temperature of 56°C, nonspecific amplicons in addition to the targeted ORF8 DNA fragment were observed. At an annealing temperature of 64°C, many of the V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 strains did not exhibit positive amplification of the targeted DNA.

Sensitivity of PCR detection for V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6.

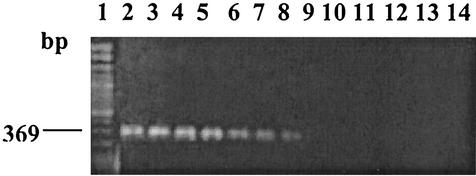

A minimum of 1 pg of purified genomic DNA from V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 TX-2062 exhibited a detectable level of an amplified ORF8 DNA band with the expected length of 369 bp in an agarose gel (Table 4; Fig. 1). This detection level of 1 pg of genomic DNA has been determined to be equivalent to approximately 103 V. parahaemolyticus cells (2, 5). The detection level of V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 in sterile MilliQ water and in gulf water was approximately 103 cells/ml (Table 4). The levels of detection in seeded gulf water purified with the FastDNA SPIN kit or the UltraClean Soil DNA kit were 104 and 105 cells per 100-ml sample, respectively (Table 4). These results were found to be consistent within all three replicates for each of the extraction methods.

TABLE 4.

Summary of results for the detection of V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 in gulf water

| Water or kit | Detection of O3:K6 at indicated number of cells

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 106 | 105 | 104 | 103 | 102 | 101 | 100 | |

| MilliQ water | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| Boiled gulf water | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| FastDNA SPIN kit | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| UltraClean soil DNA kit | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

FIG.1.

PCR sensitivity as determined by using primers F-O3MM824 and R-O3MM1192 and purified target DNA from V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 TX-2062. Lane 1, Clone-Sizer (Norgen, Inc.) DNA ladder; lane 2, 1 μg of DNA; lane 3, 0.1 μg of DNA; lane 4, 0.01 μg of DNA; lane 5, 1 ng of DNA; lane 6, 0.1 ng of DNA; lane 7, 0.01 ng of DNA; lane 8, 1 pg of DNA; lane 9, 0.1 pg of DNA; lane 10, 0.01 pg of DNA; lane 11, 1 fg of DNA; lane 12, 0.1 fg of DNA; lane 13, 0.01 fg of DNA; lane 14, PCR negative control.

Detection of V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 cultures after extended incubation at various temperatures.

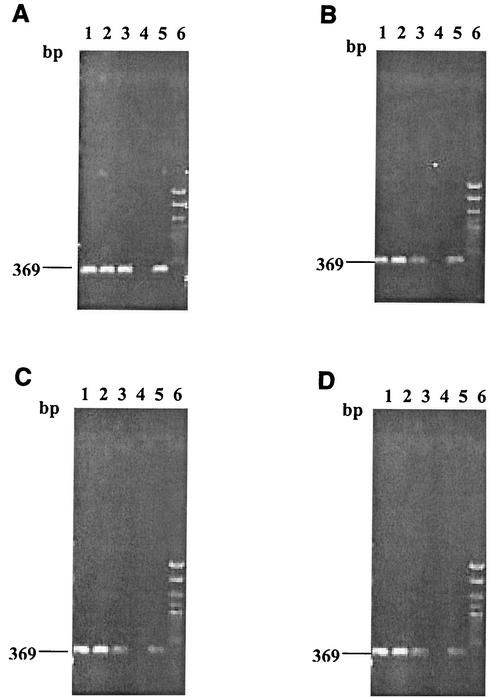

The targeted ORF8 DNA fragment was detected by PCR amplification in all cultures initially and at 7, 21, and 28 days of incubation at various temperatures (4, 15, and 21 ± 1°C) (Fig. 2). The numbers of viable cells in cultures kept at room temperature and at 15°C increased from 1 × 104 (standard deviation [SD] = ±0.002; n = 3) to 3 × 104 (SD = ±0.004; n = 3) and 1.7 × 104 (SD = ±0.002; n = 3) cells per ml, respectively. However, the culture kept at 4°C exhibited some decrease in viable-cell plate counts from 1 × 104 to 3 × 103 (SD = ±0.004; n = 3) cells per ml. PCR-amplified DNA bands with an expected molecular size of 369 bp were evidenced for all three cultures during the 28 days of incubation (Fig. 2). There was a noticeable decrease in the intensities of the amplified DNA bands from cultures incubated at cold temperatures between the initial and successive periods of incubation. All three replicates for this experiment exhibited identical results.

FIG. 2.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR-amplified ORF8 DNA segments from V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 cultures incubated at various temperatures. Lanes 1, culture at room temperature; lanes 2, culture at 15°C; lanes 3, culture at 4°C; lanes 4, PCR negative control; lanes 5, PCR positive control; lanes 6, DNA size markers. (A) Samples subjected to PCR amplification immediately after they were transferred to the temperatures noted above; (B to D) samples kept at the noted temperatures for 7 days (B), 21 days (C), and 28 days (D).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have successfully selected and tested oligonucleotide primers and a target that allowed a comprehensive and specific detection of the newly emerged pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 pandemic strains. We were able to select a single set of primers to establish a PCR-based method of detection of all pandemic isolates, including those isolated from the United States. Therefore, reliable and specific detection of this pathogen can be achieved by using these primers and the optimized PCR parameters as described in this study. The positive PCR amplification of ORF8 in O4:K68 and O1:KUT implies that these strains have a close relationship to O3:K6. In previous studies, these strains have been shown to contain the ORF8 DNA segment (12, 15). Comparison of the genetic backgrounds of the strains confirmed that they are virtually indistinguishable from one another. In addition, like V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 strains, these two strains are reported to be pathogenic to humans (10, 15). Based on these experimental results, it is believed that the O4:K68 and O1:KUT strains evolved from the newly emerged O3:K6 clone (9, 13). Therefore, PCR amplification detection of O4:K68 and O1:KUT along with the O3:K6 serotype seems to be beneficial for increasing the safety of shellfish for consumers.

A PCR detection of the pathogenic strains of V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 based on the mismatched nucleotide at the 7-base position of the toxRS gene sequence has been reported (17). However, in that study a relatively small number of bacterial species were tested, so it is not clear to what extent the results can be generalized. In a previous study, a riboprint method was used to analyze the genomic fingerprints of newly emerged pathogenic strains of V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 from the outbreak in Texas (14). However, in this study the ribotyping method could not establish a meaningful genetic correlation among the strains isolated from several outbreaks in the United States. Moreover, the riboprint approach may not be suitable for the purpose of routine monitoring of shellfish and shellfish-growing waters for the presence of this pathogen. In another study, the use of enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus (ERIC) PCR followed by conventional PCR amplification of a unique 327-bp fragment was described to be specific for the detection of the newly emerged pathogenic strains of V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 (16). However, in this study, only 18 such isolates were tested, among which 15 strains exhibited an 850-bp unique amplicon following amplification by the ERIC PCR method. In addition, only 7 out of 18 V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 U.S. outbreak isolates exhibited positive amplicons when they were tested with the conventional PCR method using selected oligonucleotide primers on a 327-bp segment of this unique DNA. Therefore, the specificity of these oligonuceotide primers in a conventional PCR-based method of detection of this pathogen that targets a unique DNA fragment obtained by using the ERIC PCR approach does not seem to be reliable. Typing newly emerged pathogenic V. parahaaemolyticus O3:K6 strains from the 1996 Texas outbreak using real-time fluorogenic PCR-based identification of the hemolysin genes was reported (Blackstone, Abstr. 101st Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 2001). However, no ORF8 was identified in these strains by this method. Since no control samples were described in this study, it is not clear whether the negative detection of ORF8 in these strains was due to the lack of optimization of the real-time PCR amplification procedure or the inappropriate selection of the primers, as we discovered sequence variations within the 1,114-bp segment of the ORF8 DNA from various isolates of the newly emerged V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 strains.

Currently, there is no specific guideline that describes a minimum level of V. parahaemolyticus in gulf water and shellfish that could potentially be hazardous to humans. However, the minimum level of detection of 103 V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 cells in seeded gulf water that was achieved in this study simply by boiling the samples falls well below the sensitivity of 5 × 103 V. parahaemolyticus in 10 g of oyster tissue homogenates (7). The less sensitive detection of this pathogen with the samples purified by the commercially available kits was possibly due to the loss of the targeted DNA during multiple processing steps. Further study or modification of the commercially available DNA purification kits is necessary to achieve the necessary sensitivity for the detection of this pathogen in shellfish and shellfish-growing waters. Positive PCR detection of slow-growing cultures grown in gulf water at various temperatures for almost a month confirms the applicability of this methodology in natural samples. The ability to specifically detect the newly emerged V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 strains in seeded gulf water suggests that this pathogenic organism could be detected in natural gulf waters and possibly in ship ballast water. Because it is known that all newly emerged pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 isolates are derived from a single clone, this strain has likely been transported from one geographical location to another. There is evidence that an epidemic strain of V. cholerae O1 spread to Gulf Coast waters via cargo ship ballast water in 1991 (19). Therefore, identification of this organism in ballast water might help prevent its spread to new locations. Also, the present study provides the premise for developing a rapid, real-time fluorogenic and gene array-based detection of this pathogen in marine and coastal waters. However, further optimization of the PCR amplification protocol and hybridization reactions may be necessary to achieve these objectives. Positive detection of this pathogen in gulf water, especially in the oyster-harvesting locations, may provide an early warning of the potential hazard of O3:K6 contamination. This warning may help initiate further confirmatory tests of the oyster samples before they are shipped for consumption. Specific detection of newly emerged pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 in coastal and ship ballast waters may provide an early warning which could reduce the outbreaks of gastroenteritis that result from its ingestion in contaminated seafood.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by funding from the Mississippi Alabama SeaGrant Consortium, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Department of Commerce, and University of Alabama at Birmingham under research grant NA86RG0039-4 (project R/SP-1).

We thank Angelo Depaola and Charles A. Kaysner for providing us with the V. parahaemolyticus strains and for their helpful suggestions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atlas, R. M. 1993. Handbook of microbiological media, p. 529. CRC Press, Inc., Boca Raton, Fla.

- 2.Atlas, R. M., and A. K. Bej. 1990. Detection of bacterial pathogens in environmental water samples by using polymerase chain reaction and gene probe, p. 399-406. In M. Innis, D. Gelfand, J. Sninsky, and T. White (ed.), A guide to methods and applications: a laboratory manual. Academic Press, Orlando, Fla.

- 3.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Smith, J. G. Seidman, and K. Struhl (ed.). 1987. Current protocols in molecular biology, p. 2.10-2.11. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 4.Bej, A. K., D. P. Patterson, C. W. Brasher, C. L. Vickery, D. D. Jones, and C. A. Kaysner. 1999. Detection of total and hemolysin-producing Vibrio parahaemolyticus in shellfish using multiplex PCR amplification of tl, tdh and trh. J. Microbiol. Methods 36:215-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bej, A. K., M. H. Mahbubani, and R. M. Atlas. 1991. Amplification of nucleic acids by polymerase chain reaction and other methods. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 16:301-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhuiyan, N. A., M. Ansaruzzaman, M. Kamruzzaman, K. Alam, N. R. Chowdhury, M. Nishibuchi, S. M. Faruque, D. A. Sack, Y. Takeda, and G. B. Nair. 2002. Prevalence of the pandemic genotype of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in Dhaka, Bangladesh, and significance of its distribution across different serotypes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:284-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, Food and Drug Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2000. Draft risk assessment on the public health impact of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in raw molluscan shellfish. Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, Washington, D.C.

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1999. Outbreak of Vibrio parahaemolyticus infections associated with eating raw oysters—Pacific Northwest, 1997. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 47:457-462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiou, C.-S., S.-Y. Hsu, S.-I. Chiu, T.-K. Wang, and C.-S. Chao. 2000. Vibrio parahaemolyticus serovar O3:K6 as cause of unusually high incidence of food-borne disease outbreaks in Taiwan from 1996 to 1999. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:4621-4625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chowdhury, N. R., S. Chakraborty, T. Rammamurthy, M. Nishibuchi, S. Yamasaki, Y. Takeda, and G. B. Nair. 2000. Molecular evidence of clonal Vibrio parahaemolyticus pandemic strains. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 6:631-636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cordova, J. L., J. Astorga, W. Silva, and C. Riquelme. 2002. Characterization by PCR of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolates collected during the 1997-1998 Chilean outbreak. Biol. Res. 35:433-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daniels, N. A., B. Ray, A. Easton, N. Marano, E. Kahn, A. L. McShan, L. Del Rosario, T. Baldwin, M. A. Kingsley, N. D. Puhr, J. G. Wells, and F. J. Angulo. 2000. Emergence of a new Vibrio parahaemolyticus serotype in raw oysters. JAMA 284:1541-1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DePaola, A., C. A. Kaysner, J. Bowers, and D. W. Cook. 2000. Environmental investigations of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in oysters after outbreaks in Washington, Texas, and New York (1997 and 1998). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4649-4654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gendel, S. M., J. Ulaszek, M. Nishubichi, and A. DePaola. 2001. Automated ribotyping differentiates Vibrio parahaemolyticus O3:K6 strains associated with a Texas outbreak from other clinical strains. J. Food Prot. 64:1617-1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iida, T., A. Hattori, K. Tagomori, H. Nasu, R. Naim, and T. Honda. 2001. Filamentous phage associated with recent pandemic strains of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:477-478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan, A. A., S. McCarthy, R. F. Wang, and C. E. Cerniglia. 2002. Characterization of United States outbreak isolates of Vibrio parahaemolyticus using enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus (ERIC) PCR and development of a rapid PCR method for detection of O3:K6 isolates. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 206:209-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsumoto, C., J. Okuda, M. Ishibashi, M. Iwanaga, P. Garg, T. Rammamurthy, H.-C. Wong, A. Depaola, Y. B. Kim, M. J. Albert, and M. Nishibuchi. 2000. Pandemic spread of an O3:K6 clone of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and emergence of related strains evidenced by arbitrarily primed PCR and toxRS sequence analyses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:578-585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCarthy, S. A., A. DePaola, C. A. Kaysner, W. E. Hill, and D. W. Cook. 2000. Evaluation of nonisotopic DNA hybridization methods for detection of the tdh gene of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Food Prot. 63:1660-1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nasu, H., T. Iida, T. Sugahara, Y. Yamaichi, K.-S. Park, K. Yokoyama, K. Makino, H. Shinagawa, and T. Honda. 2000. A filamentous phage associated with recent pandemic Vibrio parahaemolyticus O3:K6 strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2156-2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okuda, J., M. Ishibashi, E. Hayakawa, T. Nishino, Y. Takeda, A. K. Mukhopadhyay, S. Garg, S. K. Bhattacharya, G. B. Nair, and M. Nishibuchi. 1997. Emergence of a unique O3:K6 clone of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in Calcutta, India, and isolation of strains from the same clonal group from Southeast Asian travelers arriving in Japan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:3150-3155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rychilk, W., and R. E. Rhoads. 1989. A computer program for choosing optimal oligonucleotides for filter hybridization, sequencing and in vitro amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 17:8543-8551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith, J. M., E. J. Feil, and N. H. Smith. 2000. Population structure and evolutionary dynamics of pathogenic bacteria. Bioessays 22:1115-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smolikova, L. M., I. M. Lomov, T. V. Khomenko, G. P. Murnachev, T. A. Kudriakova, O. P. Fetsailova, E. M. Sanamiants, L. D. Makedonova, G. V. Kachkina, and E. N. Golenishcheva. 2001. Studies on halophilic vibrios causing a food poisoning outbreak in the city of Vladivostok. Zh. Mikrobiol. Epidemiol. Immunobiol. 6:3-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sparagano, O. A., P. A. Robertson, I. Purdom, J. McInnes, Y. Li, D. H. Yu, Z. J. Du, H. S. Xu, and B. Austin. 2000. PCR and molecular detection for differentiating Vibrio species. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 969:60-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Twedt, R. M. 1989. Vibrio parahaemolyticus, p. 552-554. In M. P. Doyle (ed.), Foodborne bacterial pathogens. Marcel Dekker Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 26.Waldor, M. K., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1996. Lysogenic conversion by a filamentous phage encoding cholera toxin. Science 272:1910-1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]