Abstract

The homology model of protein Rv2579 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv was compared with the crystal structure of haloalkane dehalogenase LinB from Sphingomonas paucimobilis UT26, and this analysis revealed that 6 of 19 amino acid residues which form an active site and entrance tunnel are different in LinB and Rv2579. To characterize the effect of replacement of these six amino acid residues, mutations were introduced cumulatively into the six amino acid residues of LinB. The sixfold mutant, which was supposed to have the active site of Rv2579, exhibited haloalkane dehalogenase activity with the haloalkanes tested, confirming that Rv2579 is a member of the haloalkane dehalogenase protein family.

Haloalkane dehalogenase is a key enzyme for degradation of synthetic haloalkanes that occur as soil pollutants (11). Haloalkane dehalogenase catalyzes dehalogenation by a hydrolytic mechanism and belongs to the α/β-hydrolase family. The reaction mechanism of haloalkane dehalogenase (DhlA) from Xanthobacter autotrophicus GJ10 was studied in detail by crystallographic and site-directed mutagenesis analyses (27, 30). The 1,3,4,6-tetrachloro-1,4-cyclohexadiene (1,4-TCDN) halidohydrolase (LinB), which is involved in the biochemical pathway responsible for utilization of the halogenated organic insecticide γ-hexachlorocyclohexane (also called γ-benzenehexachloride or lindane) in Sphingomonas paucimobilis UT26, also belongs to the family of haloalkane dehalogenases (19, 22). LinB not only converts 1,4-TCDN to 2,5-dichloro-2,5-cyclohexadiene-1-ol but also converts various kinds of haloalkanes to their corresponding alcohols (20). A catalytic triad (i.e., nucleophile-histidine-acid) is essential for the reactions catalyzed by members of the α/β-hydrolase family. Amino acid residues for the catalytic triad of LinB were proposed to be D108, H272, and E132 based on a site-directed mutagenesis analysis (10).

Haloalkane dehalogenase is also fascinating as a material for studying structure-function relationships of enzymes. To date, three-dimensional structures of the DhlA (30), DhaA (23), and LinB (17) proteins have been determined, and they have been used to study differences in substrate specificity (4). Furthermore, a theoretical analysis of the substrate specificities of these three enzymes was performed by using the multiple computer-automated structure evaluation method (5). Recently, the substrate ranges of haloalkane dehalogenases were altered by both rational site-directed mutagenesis (9) and directed evolution (2).

For a long time it was believed that haloalkane dehalogenases are present only in soil bacteria colonizing contaminated environments (7). Recently, it was found that Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv, whose complete genome has been sequenced (3), possesses genes encoding putative haloalkane dehalogenases on its chromosome (4). Furthermore, hydrolytic dehalogenation was shown to occur in a number of different mycobacteria (12). However, the function and features of the enzymes are still under investigation (13). Rv2579, one such putative dehalogenases from H37Rv, is highly homologous to haloalkane dehalogenase LinB (68% sequence identity). Sequence analysis revealed that Rv2579 has the conserved catalytic triad Asp-His-Glu (4), suggesting that this protein potentially can catalyze dehalogenation by a hydrolytic mechanism. However, it is not obvious that halogenated substrates can bind to its active site. One of purposes of this study was to confirm that Rv2579 is a haloalkane dehalogenase. Another aspect of this study involved experimental evolution of LinB. Since we changed an active site and an entrance tunnel of LinB into those of Rv2579 using cumulative mutagenesis, we could also characterize enzymes that are intermediate between LinB and Rv2579.

Design of mutations.

The amino acid sequence of Rv2579 was aligned with that of LinB (Fig. 1). The sequences were obtained from genetic databases by using the following GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ accession numbers: D14594 for the haloalkane dehalogenase from S. paucimobilis UT26 (LinB) (19) and Z77724 for the putative haloalkane dehalogenase from M. tuberculosis H37Rv (Rv2579) (25). A pairwise alignment of the protein sequences was performed manually by using Cameleon 3.14a (Oxford Molecular, Oxford, United Kingdom). The amino acid residues of an active site and entrance tunnel of LinB were deduced from the X-ray structure. In the alignment, six substitutions between LinB and Rv2579 were identified in 19 amino acid residues which form the active site and the entrance tunnel of LinB (Fig. 1). The model of Rv2579 was constructed (data not shown) by using the method of satisfaction of spatial restraints as implemented in the software Modeller 6.0a (26). The crystal structure of the haloalkane dehalogenase LinB (17) served as the template structure (PDB accession code 1cv2). The correctness of the model was tested by analyzing the stereochemical quality by using PROCHECK 3.0 (15), the packing quality was tested by using bump checks, and the folding reliability was analyzed by using 3D-1D (16) and PROSAII 3.0 (28). Using the model, we confirmed that (i) the position of the catalytic triad in the protein structure is the same in LinB and Rv2579, (ii) no additional amino acid residues form the active site of Rv2579, and (iii) the tunnel leading to the active site of Rv2579 contains residues analogous to those in LinB. In other words, we confirmed that the six amino acid residues indicated in Fig. 2 account for most of the differences between the active sites of LinB and Rv2579.

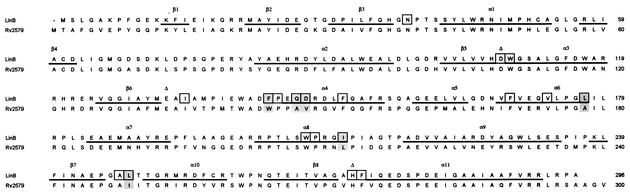

FIG. 1.

Alignment of amino acid sequences of LinB and Rv2579. The secondary structure elements (indicated by lines under the sequence), the catalytic triad (indicated by triangles above the sequence), and the active site and tunnel residues (indicated by boxes) of LinB were deduced from the crystal structure (17). The active site residues that are different in LinB and Rv2579 are shaded.

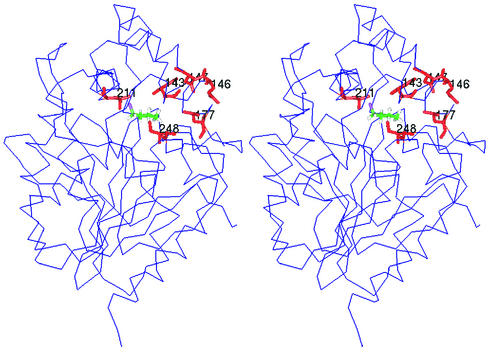

FIG. 2.

Stereo picture of the three-dimensional structure of haloalkane dehalogenase LinB, with the mutated residues indicated. The protein structure is represented by the alpha trace; the substrate molecule 1-chlorobutane (colored by atom type) docked to the active site and mutated amino acid residues (in red) are represented by sticks.

Construction of mutants by cumulative mutagenesis.

Because His-tagged LinB was used as a template, all the mutant proteins were His tagged. Although His-tagged LinB showed an average of 80% of the activity of the wild-type LinB for 10 different substrates (21), the decreases were very similar for different substrates, and the standard deviation was 5.5%. The small reduction in activity was independent of the substrate shape, size, or number of substituents. The order of mutations was selected to avoid inactivation of the enzyme at an early stage of cumulative mutagenesis. In brief, the mutations were introduced from outside to inside. First, relatively less important surface residues (Q146 and D147) were mutated. A double mutant (Q146A+D147V) was constructed, because it was practical from an experimental point of view. Then a more important surface residue (L177) was mutated. Second, the active site residues (I211, L248, and F143) were mutated. Since I211L and L248I were expected to be able to compensate for each other (see below), the mutations were introduced in the order I211L-L248I-F143W. The F143W mutation could be introduced before the I211L and L248I mutations. Mutagenesis of LinB was performed by using the principle of the LA PCR in vitro mutagenesis kit (TaKaRa Shuzo Co., Kyoto, Japan) according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer, except that we used Pyrobest DNA polymerase (TaKaRa), whose fidelity is very high. All of the nucleotide sequences of mutants were confirmed by the dideoxy chain termination method with an automated DNA sequencer (ABI PRISM 310 genetic analyzer; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). The following oligonucleotides were used: Q146A+D147V (5′-CAG ATC GCG AAC CGC TTC GGG AAA ATC-3′), L177A (5′-GCG CAG GAT CGC TCC GGG GAG-3′), I211L (5′-GAT CGG GAG TTG GCG AGG-3′), L248I (5′-GCC CGT GGT GAT GGC TCC CGG-3′), and F143W (5′-CGC TTC GGG CCA ATC CGC CCA-3′).

Overexpression and purification of protein mutants.

To overproduce LinB mutants in Escherichia coli, plasmids for overexpression were constructed from pAQN, which has the same structure as pAQI (29) except for differences in the aqualysin I-coding region. Plasmid pAQN was digested with EcoRI and HindIII in order to replace the 1.8-kb aqualysin I-coding fragment with the 0.9-kb EcoRI-HindIII fragment encoding the His-tagged LinB mutants. In these plasmids, His-tagged linB mutants were transcribed by the tac promoter (Ptac) under the control of lacIq. E. coli JM109 containing these plasmids was cultured in 2 liters of Luria broth at 37°C. Induction of enzyme expression was initiated by addition of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside to a final concentration of 0.5 mM, when the culture reached an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6. The cells were harvested and disrupted by sonication by using a Sonopuls GM70 (Bandelin, Berlin, Germany). The supernatant was used after centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1 h. The crude extract was purified further on an Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid Sepharose column (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). The His-tagged LinB (21) was bound to the resin in equilibrating buffer (20 mM potassium phosphate buffer [pH 7.5] containing 0.5 M sodium chloride and 10 mM imidazole). Unbound and weakly bound proteins were washed out by the buffer containing 45 mM imidazole. The His-tagged enzyme was then eluted by the buffer containing 250 mM imidazole. The active fractions were pooled and dialyzed against 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) overnight. The enzyme was stored in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 10% glycerol and 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol. All the mutant enzymes were expressed well and could be purified to homogeneity (data not shown).

Biochemical characterization of catalytic activity.

Steady-state kinetic constants were determined with two substrates, 1-chlorobutane and 1,3-dibromopropane, for the His-tagged wild-type enzyme and all five mutants (Table 1). The substrate 1-chlorobutane was chosen because it is often used as the reference compound for kinetic characterization of the haloalkane dehalogenases, and 1,3-dibromopropane is one of the best substrates for these enzymes irrespective of the specificity subclass (5). The catalytic activities of LinB mutants were assessed by determining the substrate and product concentrations by gas chromatography with a Trace GC 2000 (Thermo Finnigan, San Jose, Calif.) equipped with a flame ionization detector and a capillary column (DB-FFAP; 30 m by 0.25 mm by 0.25 μm; J&W Scientific, Folsom, Calif.). The dehalogenation reaction was performed in 25-ml Reacti-Flasks closed with Mininert valves in a shaking water bath at 37°C. The reaction mixtures consisted of the enzyme preparation (4 mg/liter) and various concentrations of the substrates 1-chlorobutane (0.1 to 6.4 mM) and 1,3-dibromopropane (0.1 to 25.6 mM). The reactions were stopped by addition of methanol at three different times. The data measured in triplicate were fitted to different kinetic models. The steady-state constants (kcat and Km) were calculated by using the computer program EZ-Fit, version 1.1 (written by F. W. Perrella).

TABLE 1.

Steady-state kinetic constants for LinB and its mutants

| Substrate | Enzyme | Sp act (μmol · s−1 · mg of protein−1) | kcat (s−1) | Km (mM) | kcat/Km (mM−1 · s−1) | Ksi (mM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Chlorobutane | Wild type | 0.034 ± 0.002a | 1.11 ± 0.03 | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 4.83 | NAb |

| Q146A + D147V | 0.016 ± 0.001 | 0.65 ± 0.02 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 10.10 | NA | |

| L177A | 0.015 ± 0.003 | 0.41 ± 0.03 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 4.99 | NA | |

| I211L | 0.008 ± 0.001 | 0.27 ± 0.01 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 5.26 | NA | |

| L248I | 0.021 ± 0.002 | 0.76 ± 0.03 | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 3.58 | NA | |

| F143W | 0.018 ± 0.002 | 0.58 ± 0.03 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 4.05 | NA | |

| 1,3-Dibromopropane | Wild type | 0.094 ± 0.013 | 40.9 ± 5.2 | 24.10 ± 3.23 | 1.70 | 0.49 ± 0.06 |

| Q146A + D147V | 0.034 ± 0.001 | 25.8 ± 2.6 | 5.90 ± 1.22 | 4.37 | 0.21 ± 0.04 | |

| L177A | 0.033 ± 0.005 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 30.86 | 27.20 ± 11.29 | |

| I211L | 0.072 ± 0.008 | 3.4 ± 0.7 | 0.19 ± 0.11 | 17.68 | 6.82 ± 2.31 | |

| L248I | 0.095 ± 0.006 | 20.3 ± 4.3 | 5.11 ± 2.18 | 3.96 | 1.50 ± 0.52 | |

| F143W | 0.107 ± 0.003 | 21.5 ± 2.8 | 10.07 ± 2.44 | 2.13 | 1.63 ± 0.34 |

Mean ± standard error.

NA, not applicable.

When 1,3-dibromopropane was used as the substrate, all enzymes exhibited reduced rates at higher substrate concentrations. This could be explained by the kinetic model employing the substrate inhibition effect. The correlation between the kcat values obtained for two different substrates and the correlation between specific activities were used to check the consistency of kinetic data and justified application of the substrate inhibition model for calculation of kcat values for the substrate 1,3-dibromopropane. The Pearson correlation coefficient for the specific activities of different mutants with 1-chlorobutane and 1,3-dibromopropane was only 0.43, while the correlation coefficient calculated with catalytic constants was 0.93, supporting the use of the substrate inhibition model for 1,3-dibromopropane.

The final sixfold mutant (+F143W), which was supposed to have an active site and entrance tunnel of Rv2579, showed significant haloalkane dehalogenase activity with two halogenated compounds (Table 1), confirming that the Rv2579 protein can bind haloalkanes and can convert them to products by a hydrolytic mechanism. Not only the sixfold mutant but also intermediate mutants showed haloalkane dehalogenase activity. During the cumulative mutagenesis analysis, significant changes in both the Km and kcat of evolved proteins were observed. These changes were correlated; i.e., mutants with lower activity showed improved binding and vice versa. The first double mutation, Q146A+D147V, had a positive effect on Km. The Q146A+D147Vmutant exhibited lower Michaelis constants for both 1-chlorobutane and 1,3-dibromopropane than the wild-type enzyme. The Km for 1,3-dibromopropane was further improved by monitoring mutation L177A. These findings suggest that the first three mutations had positive effects on binding affinity. Furthermore, the +L177A mutant had a significantly higher substrate inhibition constant (Ksi), suggesting that the substrate inhibition effect of 1,3-dibromopropane was weaker. When the results were considered together, the most significant enhancement of the catalytic efficiency of LinB with the substrate 1,3-dibromopropane (as quantified by kcat/Km) was due to the L177A mutation.

Biochemical characterization of substrate specificity.

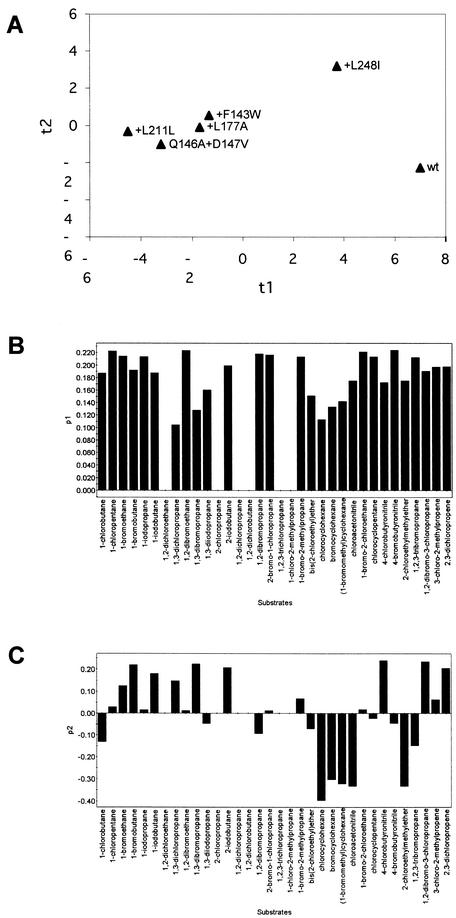

To characterize the substrate specificity of every mutant, the semiquantitative spectrophotometric method of Holloway et al. (9) as optimized for characterization of LinB mutants by Marvanova et al. (18) was used. The principle of this method is based on estimating the acidification associated with dehalogenation of the substrates. The reaction was performed in 5-ml vials closed with headspace caps. The reaction buffer consisted of 1 mM HEPES (pH 8.2), 20 mM sodium sulfate, and 1 mM EDTA. Phenol red was added to a final concentration of 25 mg/ml, and a halogenated compound was added to an apparent concentration of 10 mM. The substrate-buffer solution was mixed vigorously for 15 s with a vortex mixer and equilibrated for 30 min at room temperature in an orbital shaker to dissolve the substrate. Each microplate well received 170 μl of the reaction mixture and 40 μl of the enzyme solution (protein concentration, 5 mg/ml; pH 7.8 ± 0.03). The absorbance at 550 nm was measured for eight replicates at 25°C for 3 min at intervals of 30 s by using a SUNRISE microplate reader (TECAN, Durham, N.C.). The slope of the plot of absorbance versus time was used to quantify the rate of dehalogenation. Every mutant was tested with 34 different halogenated substrates selected by multivariate experimental design (18). The natural substrate of LinB, 1,4-TCDN, was not included in the set of substrates due to its low stability. The relative dehalogenation activities (centered and scaled to unit variance) were analyzed by principal component analysis (31) using the statistical package SIMCA P v9.0 (Umetrics AB, Umea, Sweden). Principal component analysis is an analytical method intended to extract and visualize systematic patterns or trends in large data matrices. This analysis enabled objective comparisons of the protein mutants based on their substrate specificities (i.e., classification based on simultaneous consideration of activity data measured for a large number of different substrates). Here, a large matrix of 6 × 34 data points (mutants × substrates) was summarized by just three plots. The score plot (Fig. 3A) should be examined along with loading plots (Fig. 3B and C) in order to see which substrates were responsible for separation of mutants in the horizontal and vertical directions. The separation of the mutants in the horizontal direction was based on the overall catalytic activities with many different substrates, as follows: wild type > +L248I ≫ +F143W > +L177A > Q146A+D147A > +I211L (Fig. 3A). All but nonactive substrates (Fig. 3B) contributed to this separation, which corresponded well to the large data variance (70%) in this direction. The separation of the two most active proteins, the wild type and +L248I, in the horizontal direction (Fig. 3A) accounted for 12% of the data variance (Fig. 3C). As far as substrate specificities are concerned, the wild type and the +L248I variant represent different subclasses than the rather homogeneous group of other protein mutants. Several substrates (i.e., substrates with high positive loading values in Fig. 3C) showed higher activities with +L248I than with the wild-type enzyme in the semiquantitative screening analysis. A quantitative and more sensitive gas chromatographic analysis was subsequently performed for some of these compounds (Table 2). Improved activities (about threefold improved) of +L248I with the haloalkenes 2,3-dichloropropene and 3-chloro-2-methylpropene were observed (Table 2). This important change in substrate specificity would have been missed if only steady-state kinetic experiments with two substrates had been used for characterization of the mutants.

FIG.3.

(A) Scatter plot of the first score (t1) plotted against the second score (t2). (B and C) Column plots of the first loading p1 (B) and the second loading p2 (C). The scores and loadings were obtained from the principal component analysis applied to the 6 × 34 (mutants × substrates) data matrix. The first principal component explained 70% of the data variance, and the second principal component explained 12% of the data variance.

TABLE 2.

Specific activities of wild-type LinB and mutant +L248I

| Substrate | Sp act (μmol · s−1 · mg of protein−1)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Wild type | Mutant +L248I | |

| 1-Bromoethane | 0.112 ± 0.009a | 0.119 ± 0.014 |

| 1-Chlorobutane | 0.034 ± 0.002 | 0.021 ± 0.002 |

| 1-Bromobutane | 0.051 ± 0.011 | 0.040 ± 0.011 |

| 1,3-Dichloropropane | 0.014 ± 0.001 | 0.015 ± 0.002 |

| 1,3-Dibromopropane | 0.102 ± 0.016 | 0.040 ± 0.013 |

| 3-Chloro-2-methylpropene | 0.121 ± 0.032 | 0.396 ± 0.039 |

| 2,3-Dichloropropene | 0.023 ± 0.003 | 0.063 ± 0.006 |

Mean ± standard error.

Structural interpretation of experimentally evolved mutants.

It is possible to interpret observed changes in activity and specificity in terms of structural changes introduced into LinB by each of the mutations. The Q146A mutation resulted in modification of the nose of the tunnel; however, this was not very significant. Mostly the hydrophobicity of the tunnel was changed by this mutation. More significant was the D147V substitution, which resulted in a change in the electrostatic properties of the tunnel. Lower stabilization of the substrate dipole moment and thus lower activity were expected for this mutant. The L177A mutation resulted in the most dramatic change in the catalytic efficiency of the LinB protein. This is not surprising considering the position of this residue in the wall of the tunnel leading to the enzyme active site. The side chain of residue 177 points towards the tunnel, and replacement of this residue results in a significant change in the aperture. The critical role of this residue in the size of the tunnel and thus in the binding affinity and specificity of haloalkane dehalogenases could also be deduced from the sequence alignment (4), which indicated that of all the active site and tunnel residues, residues equivalent to L177 of LinB showed the greatest variability among the different haloalkane dehalogenases. The L177A mutation enlarged the aperture of the tunnel and the active site, which resulted in easier entrance of the substrates into the active site (lower Km) but lower stabilization of the substrates in the active site during the reaction (lower kcat). The stronger substrate inhibition effect (higher Ksi) of this mutant in the reaction with 1,3-dibromopropane suggests that it can form an inactive complex with two substrate molecules more easily than the wild-type enzyme can. The I211L mutation had the opposite effect on the activity and affinity of this mutant with chlorinated and brominated substrates (Table 1). This can be explained by the fact that residue 211 is in direct van der Waals contact with the halogen atom bound to the enzyme active site. Mutation of isoleucine to leucine resulted in additional van der Waals contact between the residue and the halogen atom. Furthermore, residue 211 is located very close to W109, and a mutation can result in repositioning of its side chain. The W109 residue provides stabilization to the halogen atom bound to the enzyme active site and, more importantly, to the halide ion released from the substrate during the dehalogenation reaction (1). The conservative substitution W109L results in inactive protein (21). The L248I mutation is the first mutation that improves the catalytic activity of the protein. This effect can be due to compensation for the previous mutation I211L. Residue 248 is part of the active site, and mutation of this residue results in a change in the shape of the enzyme active site, which explains the modified substrate specificity of this mutant. This change can be magnified by the fact that the side chain of residue 248 separates the active site from a smaller cavity in the LinB protein. The F143W mutation had the opposite effect on the activity and affinity of this mutant with chlorinated and brominated substrates, as previously observed also with the +I211L mutant. Analogous to the interaction of I211 with the halide-stabilizing residue W109, F143 makes contact with the halide-stabilizing F151 residue (1). Replacement of F143 by a larger tryptophan residue would result in a repositioning of F151. The hole that accepts the halogen atom of a substrate bound in the enzyme active site can be optimal for only one type of halogen, while it is suboptimal for others. It is therefore not surprising that mutations resulting in modification of this hole result in different effects on different halogenated substrates. This has been demonstrated previously by mutagenesis of the residues in direct contact with the halogen (so-called first-shell residues F151 and F169) (1, 21) and also with the second-shell residues F154 (18), I211, and F143 (this study).

The constructed mutants, including the sixfold mutant, can be used for further analysis of structure-function relationships of haloalkane dehalogenases. We cannot exclude the possibility that the final mutant does not have exactly the same active site as Rv2579, since it has been shown previously that the active site can be remodeled even by mutation of residues remote from the active site (24). However, the high sequence identity of the LinB and Rv2579 enzymes (68%) and the missing insertions or deletions in the alignment imply that their Cα atoms deviate only slightly (root mean square deviation, ∼0.6 Å), the cores of these proteins are almost identical, and the proteins vary mainly in the composition and orientation of the amino acid side chains. Recent computational analysis of the substrate specificities of DhlA (14) and LinB (6) revealed that the binding of substrates to the buried active sites seems to be determined exclusively by the residues in the first and second shells of the active site and in the tunnel. Since the hydrolytic activity of Rv2579 can be inferred from the presence of the catalytic triad and since the present mutagenesis study confirmed the ability of a sixfold mutant of LinB to bind the halogenated substrates, we are very confident about the dehalogenating activity of the Rv2579 protein. To analyze this enzyme further, the role of Rv2579 in Mycobacterium should be analyzed.

Acknowledgments

Anonymous referees are acknowledged for constructive suggestions leading to improvement of the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by a grant-in-aid for scientific research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan. J.D. acknowledges grant LN00A016 from the Czech Ministry of Education.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bohac, M., Y. Nagata, Z. Prokop, M. Prokop, M. Monincova, J. Koca, M. Tsuda, and J. Damborsky. 2002. Halide-stabilizing residues of haloalkane dehalogenases studied by quantum mechanic calculations and site-directed mutagenesis. Biochemistry 41:14272-14280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bosma, T., J. Damborsky, G. Stucki, and D. B. Janssen. 2002. Biodegradation of 1,2,3-trichloropropane through directed evolution and heterologous expression of a haloalkane dehalogenase gene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3582-3587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cole, S. T., R. Brosch, J. Parkhill, T. Garnier, C. Churcher, D. Harris, S. V. Gordon, K. Eiglmeier, S. Gas, C. E. Barry III, F. Tekaia, K. Badcock, D. Basham, D. Brown, T. Chillingworth, R. Connor, R. Davies, K. Devlin, T. Feltwell, S. Gentles, N. Hamlin, S. Holroyd, T. Hornsby, K. Jagels, A. Krogh, J. McLean, S. Moule, L. Murphy, K. Oliver, J. Osborne, M. A. Quail, M.-A. Rajandream, J. Rogers, S. Rutter, K. Seeger, J. Skelton, R. Squares, S. Squares, J. E. Sulston, K. Taylor, S. Whitehead, and B. G. Barrell. 1998. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393:537-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Damborsky, J., and J. Koca. 1999. Analysis of the reaction mechanism and substrate specificity of haloalkane dehalogenases by sequential and structural comparisons. Protein Eng. 12:989-998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Damborsky, J., E. Rorije, A. Jesenska, Y. Nagata, G. Klopman, and W. J. G. M. Peijnenburg. 2001. Structure-specificity relationships for haloalkane dehalogenases. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 20:2681-2689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Damborsky, J., J. Kmunicek, T. Jedlicka, S. Luengo, F. Gago, A. R. Ortiz, and R. C. Wade. Rational re-design of haloalkane dehalogenases guided by comparative binding energy analysis. In A. Svendsen (ed.), Enzyme functionality: design, engineering and screening, in press. Marcel Dekker, New York, N.Y.

- 7.Fetzner, S., and F. Lingens. 1994. Bacterial dehalogenases: biochemistry, genetics, and biotechnological applications. Microbiol. Rev. 58:641-685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holloway, P., J. T. Trevors, and H. Lee. 1998. A colorimetric assay for detecting haloalkane dehalogenase activity. J. Microbiol. Methods 32:31-36. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holloway, P., K. L. Konke, J. T. Trevors, and H. Lee. 1998. Alternation of the substrate range of haloalkane dehalogenase by site-directed mutagenesis. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 59:520-523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hynkova, K., Y. Nagata, M. Takagi, and J. Damborsky. 1999. Identification of the catalytic triad in the haloalkane dehalogenase from Sphingomonas paucimobilis UT26. FEBS Lett. 446:177-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janssen, D. B., F. Pries, and J. R. Van der Ploeg. 1994. Genetics and biochemistry of dehalogenating enzymes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 48:163-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jesenska, A., I. Sedlacek, and J. Damborsky. 2000. Dehalogenation of haloalkanes by Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv and other mycobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:219-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jesenska, A., M. Bartos, V. Czernekova, I. Rychlik, I. Pavlik, and J. Damborsky. 2002. Cloning and expression of the haloalkane dehalogenase gene dhmA from Mycobacterium avium N85 and preliminary characterization of DhmA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3724-3730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kmunicek, J., S. Luengo, F. Gago, A. R. Ortiz, R. C. Wade, and J. Damborsky. 2001. Comparative binding energy analysis of the substrate specificity of haloalkane dehalogenase from Xanthobacter autotrophicus GJ10. Biochemistry 40:8905-8917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laskowski, R. A., M. W. McArthur, D. S. Moss, and J. M. Thornton. 1993. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26:283-291. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luthy, R., J. U. Bowie, and D. Eisenberg. 1992. Assessment of protein models with three-dimensional profiles. Nature 356:83-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marek, J., J. Vevodova, I. Kuta-Smatanova, Y. Nagata, L. A. Svensson, J. Newman, M. Takagi, and J. Damborsky. 2000. Crystal structure of the haloalkane dehalogenase from Sphingomonas paucimobilis UT26. Biochemistry 39:14082-14086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marvanova, S., Y. Nagata, M. Wimmerova, J. Sykorova, K. Hynkova, and J. Damborsky. 2001. Biochemical characterization of broad-specificity enzymes using multivariate experimental design and a colorimetric microplate assay: characterization of the haloalkane dehalogenase mutants. J. Microbiol. Methods 44:149-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagata, Y., T. Nariya, R. Ohtomo, M. Fukuda, K. Yano, and M. Takagi. 1993. Cloning and sequencing of a dehalogenase gene encoding an enzyme with hydrolase activity involved in the degradation of γ-hexachlorocyclohexane in Pseudomonas paucimobilis. J. Bacteriol. 175:6403-6410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagata, Y., K. Miyauchi, J. Damborsky, K. Manova, A. Ansorgova, and M. Takagi. 1997. Purification and characterization of haloalkane dehalogenase of a new substrate class from a γ-hexachlorocyclohexane-degrading bacterium, Sphingomonas paucimobilis UT26. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3707-3710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagata, Y., K. Hynkova, J. Damborsky, and M. Takagi. 1999. Construction and characterization of histidine-tagged haloalkane dehalogenase (LinB) of a new substrate class from a γ-hexachlorocyclohexane-degrading bacterium, Sphingomonas paucimobilis UT26. Protein Express. Purif. 17:299-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagata, Y., K. Miyauchi, and M. Takagi. 1999. Complete analysis of genes and enzymes for γ-hexachlorocyclohexane degradation in Sphingomonas paucimobilis UT26. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 23:380-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newman, J., T. S. Peat, R. Richard, L. Kan, P. E. Swanson, J. A. Affholter, I. H. Holmes, J. F. Schindler, C. J. Unkefer, and T. C. Terwilliger. 1999. Haloalkane dehalogenase: structure of a Rhodococcus enzyme. Biochemistry 38:16105-16114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oue, S., A. Okamoto, T. Yano, and H. Kagamiyama. 1999. Redesigning the substrate specificity of an enzyme by cumulative effects of the mutations of non-active site residues. J. Biol. Chem. 274:2344-2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Philipp, W. J., S. Poulet, K. Eiglmeier, L. Pascopella, V. Balasubramanian, B. Heym, S. Bergh, B. R. Bloom, W. R. Jacobs, and S. T. Cole. 1996. An integrated map of the genome of the tubercle bacillus, Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv, and comparison with Mycobacterium leprae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:3132-3137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sali, A., and T. L. Blundell. 1993. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 234:779-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schanstra, J. P., J. Kingma, and D. B. Janssen. 1996. Specificity and kinetics of haloalkane dehalogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 271:14747-14753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sippl, M. J. 1993. Recognition of errors in three-dimensional structures of proteins. Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 17:355-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Terada, I., S.-T. Kwon, Y. Miyata, H. Matsuzawa, and T. Ohta. 1993. Unique precursor structure of an extracellular protease, aqualysin I, with NH2-and COOH-terminal pro sequences and processing in E. coli. J. Biol. Chem. 265:6576-6581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verschueren, K. H. G., F. Seljee, H. J. Rozeboom, K. H. Kalk, and B. W. Dijkstra. 1993. Crystallographic analysis of the catalytic mechanism of haloalkane dehalogenase. Nature 363:693-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wold, S., K. Esbensen, and P. Geladi. 1987. Principal component analysis. Chemometr. Intel. Lab. Systems 2:37-52. [Google Scholar]