Abstract

Interaction between CD40L (CD154) on activated T cells and its receptor CD40 on antigen-presenting cells has been reported to be important in the resolution of infection by mycobacteria. However, the mechanism(s) by which Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) up-regulates membrane expression of CD40L molecules is poorly understood. This study was done to investigate the role of the nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) signaling pathway in the regulation of CD40L expression in human CD4+ T cells stimulated with BCG. Specific pharmacologic inhibition of the NF-κB pathway revealed that this signaling cascade was required in the regulation of CD40L expression on the surface of BCG-activated CD4+ T cells. These results were further supported by the fact that treatment of BCG-activated CD4+ T cells with these pharmacological inhibitors significantly down-regulated CD40L mRNA. In this study, inhibitor κBα (IκBα) and IκBβ protein production was not affected by the chemical protease inhibitors and, more importantly, BCG led to the rapid but transient induction of NF-κB activity. Our results also indicated that CD40L expression on BCG-activated CD4+ T cells resulted from transcriptional up-regulation of the CD40L gene by a mechanism which is independent of de novo protein synthesis. Interestingly, BCG-induced activation of NF-κB and the increased CD40L cell surface expression were blocked by the protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitors 1-[5-isoquinolinesulfonyl]-2-methylpiperazine and salicylate, both of which block phosphorylation of IκB. Moreover, rottlerin a Ca2+-independent PKC isoform inhibitor, significantly down-regulated CD40L mRNA in BCG-activated CD4+ T cells. These data strongly suggest that CD40L expression by BCG-activated CD4+ T cells is regulated via the PKC pathway and by NF-κB DNA binding activity.

Interaction between the CD40 receptor on antigen-presenting cells (APC) and its ligand (CD40L) on activated T cells plays an important role in many immune responses. CD40 is a 50-kDa type I transmembrane protein belonging to the tumor necrosis factor receptor family (26). CD40 ligand, also known as CD154, is a 261-amino-acid-long type II transmembrane protein with a molecular mass of 33 kDa and is a member of the tumor necrosis factor family of cytokines (1, 12). Its gene is preferentially expressed in activated CD4+ T cells and mast cells, but the surface protein can also be detected on monocytes and CD8+ T cells (2, 13). CD40-CD40L interactions are known to activate APC such as macrophages for their microbicidal activity (14, 17) and play a critical role in immunity to intracellular pathogens by up-regulating the production of interleukin 12 (IL-12) (9, 15, 16). CD40L expression in human T cells is regulated at multiple intracellular levels, beginning with transcription (39). Increased amounts of CD40L mRNA and activation of a relevant transcription factor NF-κB, have been reported in human T cells after activation with anti-CD3 or phorbol myristate acetate (20, 31, 32). NF-κB is a ubiquitous dimeric transcription factor that is retained in the cytoplasm in a latent form as a heterotrimeric complex consisting of p50, p65 subunits, and an inhibitor, IκB (inhibitor of κB). The nature of the signals that lead to activation of NF-κB strongly implies that this nuclear factor plays a critical role in the activation of immune cells (3, 11, 24). It has been demonstrated that NF-κB is involved in mycobacterial infections, since expression of IL-2 receptor and activation of IL-6 and IL-8 by Mycobacterium tuberculosis are mediated by this nuclear factor (37, 38, 41, 42). Moreover, a purified protein derivative induces the activation of NF-κB in monocytes from patients with tuberculosis (40). However, little is known about the role of NF-κB in regulating CD40L expression on Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG)-activated T cells. Therefore, the present study was undertaken to determine the role of NF-κB in BCG-mediated up-regulation of CD40L expression on human CD4+ T cells. Furthermore, we evaluated the role of protein kinase C (PKC) in BCG-induced NF-κB activation and the role of phosphorylation of the IκB protein in BCG-induced activation of NF-κB.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

N-acetyl-Leu-Leu-norleucinal (ALLN) was purchased from Boehringer Mannheim (Indianapolis, Ind.). 1-[5-isoquinolinesulfonyl]-2-methylpiperazine (H-7), pyrrolidinedithiocarbamate (PDTC), cycloheximide (CHX), actinomycin D (Act D), and salicylate were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.). The PKC inhibitor rottlerin was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, Calif.). Anti-IκBα and anti-IκBβ antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, Calif.). Live M. bovis BCG Danish strain 1331 was kindly supplied by J. Ruiz-Puente (Birmex, Mexico City, Mexico). BCG was grown at 37°C in Sauton medium with stationary tissue culture flasks. Mycobacterial viability, as assessed by the number of CFU, was 60 to 70%.

Cell culture.

Blood was obtained by peripheral venipuncture of healthy adult volunteers. After isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells by density centrifugation over Ficoll-Hypaque gradient (d = 1.007, Histopaque; Sigma); the CD4+-T-cell subset was purified by positive selection with magnetic microbead-coated antibody (Miltenyi Biotec, Gladbach, Germany). Cells were incubated with beads conjugated to monoclonal mouse anti-human CD4 antibody (Leu-3a). The purity of CD4+ T cells after positive selection was confirmed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). One cycle of selection was sufficient to obtain ≥93% CD4+ T cells. Autologous APC were placed in 24-well flat-bottom plates and infected with M. bovis BCG. The multiplicity of infection (MOI) was 3 live M. bovis BCG organisms per cell. After infection, cells were washed twice with warm RPMI 1640 medium to remove extracellular bacteria, treated with 50 μg of mitomycin C/ml, and then cultured in fresh RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U of penicillin/ml, 100 μg of streptomycin/ml, and 10% fetal calf serum in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. Then, purified CD4+ T cells were added to the wells (the equivalent of 1 T cell per APC). In some experiments, T cells were preincubated with medium or various inhibitors for 60 min, washed by RPMI 1640, and then cocultured with APC infected with BCG. The optimal concentrations of the inhibitors were determined in advance.

Flow cytometry.

Cells were suspended in 100 μl of phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% (wt/wt) bovine serum albumin (Sigma). The cells were incubated for 30 min at 4°C with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-CD40L monoclonal antibody (clone TRAP1), immunoglobulin G-isotype control antibody, or anti-CD69 monoclonal antibody (purchased from Becton Dickinson, San José, Calif.). After two washes, the cells were fixed with 1% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde and acquisition was performed on a FACScan (Becton Dickinson). Data were analyzed with CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson). The fluorescence of 10,000 cells was accumulated for analysis.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR.

Total RNA from 107 T lymphocytes was isolated by the method of Chomczynski and Sacchi (7). Briefly, total RNA extracted with 1 ml of Trizol for 5 min at room temperature was transferred to a microcentrifuge tube, and 200 μl of chloroform was added, vortex mixed, and incubated for 10 min. After centrifugation for 5 min, the aqueous layer was transferred to a fresh tube and RNA was precipitated by adding an equal volume of isopropanol. After centrifugation, the RNA pellet was dried and dissolved in 50 μl of sterile water. The RNA concentration was determined by optical density measurements. RNA (2 μg) was reverse transcribed by using random hexamer primers (GIBCO BRL) and Superscript II reverse transcriptase (RT; GIBCO BRL), and 2 μl of the cDNA was used for specific PCR, for a total of 20 cycles in the standard reaction mixture with Taq DNA polymerase and the appropriate CD40L and actin primers (Clontech Laboratories, Palo Alto, Calif.). An aliquot of the amplified product was run on a 2% agarose gel in Tris-borate-EDTA. After electrophoresis, the gel was stained for 5 min in ethidium bromide (1%) and photographed. PCR primers for actin were used as an internal control. Bands were integrated by scanning densitometry, and values were normalized to the signal of the control actin probe.

Western blot analysis.

Cells were solubilized in lysis buffer (10 mmol of Tris/liter, 50 mmol of NaCl/liter, 5 mmol of EDTA/liter, and 1% Triton X-100 [pH 7.6]) containing 10-μg/ml concentrations of the protease inhibitors aprotinin, leupeptin, water-soluble phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and pepstatin A and cleared by centrifugation. After the protein content was normalized between samples, equal amounts of protein from each sample were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. The blots were then washed in Tris-Tween-buffered saline, blocked overnight with 5% (wt/vol) nonfat dry milk, and probed with polyclonal anti-IκBα and anti-IκBβ antibodies in 5% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin dissolved in Tris-Tween-buffered saline. The blots were then washed three times and incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. Bound antibody was detected by using a Western blotting detection kit (Amersham, Aylesbury, United Kingdom).

Statistical methods.

The values were compared by Student's t test. For all statistical analysis, differences at P < 0.01 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Inhibitors of NF-κB activation inhibit expression of CD40L levels on the surface of BCG-activated CD4+ T cells.

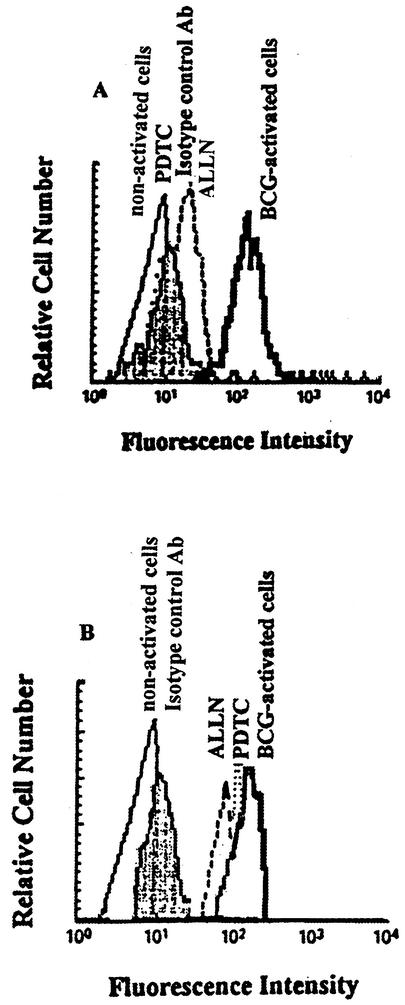

In preliminary experiments, the kinetics of CD40L expression revealed a significant expression of CD40L after 24 h of culture. This is consistent with previous results demonstrating that strong CD40L expression occurs 24 h after stimulation (21). In order to determine whether NF-κB is involved in the regulation of CD40L expression, CD4+ T cells were pretreated with ALLN, a well-described inhibitor of NF-κB activation which prevents degradation of IκB and eventually results in a lack of translocated NF-κB in the nucleus (30). After incubation, cells were activated with autologous APC infected with BCG at an MOI of 3 or left nonactivated. The cells were harvested at 24 h, and cell surface CD40L or CD69 expression on BCG-activated CD4+ T cells was measured by FACS. As shown in Fig. 1A, high surface levels of CD40L were observed after 24 h of activation compared to nonactivated T cells (controls). However, this up-regulation is abolished by treatment with ALLN. In order to confirm these results, cells were pretreated with PDTC, another well-known inhibitor of NF-κB activation with a different mechanism of action (23), and activated with APC infected with BCG. As evident in Fig. 1A, treatment of cells with PDTC caused a significant down-regulation of CD40L expression, with significant inhibition at 89%. Cell viability, as determined by vital dye exclusion (trypan blue), was always >92% after incubation of cells for 24 h with the inhibitors at the concentrations used. In contrast, the CD69 level (used as another T-cell activation marker) was only slightly affected, indicating that the effect of the inhibitors on CD40L expression was specific (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

ALLN and PDTC inhibit CD40L surface expression on BCG-activated CD4+ T cells. CD4+ T cells were cultured in medium alone or treated with 50 μM ALLN or 100 μM PDTC for 1 h and then activated with autologous APC (infected with BCG at an MOI of 3 and treated in advance with 50 μg of mitomycin C/ml) or left unactivated for 24 h. After incubation, the cells were harvested and the surface levels of CD40L (A) or CD69 (B) on the T cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Histograms show fluorescence intensity divided into channels (abscissa) against relative cell number (ordinate). One representative experiment of five is shown.

Expression of CD40L mRNA in BCG-activated CD4+ T cells is inhibited by ALLN and PDTC.

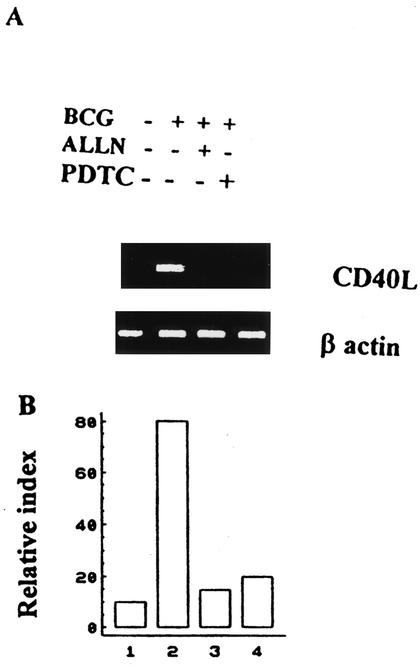

To correlate protein CD40L expression with CD40L mRNA concentrations, the levels of CD40L mRNA were measured by a semiquantitative RT-PCR method. As shown in Fig. 2, adding ALLN or PDTC to BCG-activated CD4+ T cells significantly inhibited CD40L mRNA production in contrast to the level of production obtained after BCG stimulation alone. Parallel RT-PCR showed quasi-equal amounts of β-actin mRNA in all of the RT-PCR samples, as shown in Fig. 2. The quantity of mRNA was normalized by detection of β-actin to correct for any gel-loading discrepancies. These results correlate well with the reduced surface levels of CD40L in the presence of inhibitors of NF-κB. To determine whether IκBα or IκBβ plays an important function in this pathway, we stimulated CD4+ T cells with BCG-infected APCs, and cytosolic extracts were analyzed by immunoblotting with polyclonal antibodies against IκBα and IκBβ. Immunoblotting analysis revealed that BCG led to a loss of IκBα protein, which was rapidly degraded upon stimulation (∼30 min) but reappeared within 2 h (Fig. 3A). By contrast, the IκBβ protein was less affected at early time points (30 min), but then its levels decreased gradually and almost disappeared by 2 h (Fig. 3A). Taken together, these results indicate that BCG leads to the rapid but transient induction of NF-κB activity. To examine the potential effects of ALLN and PDTC on IκB at the protein levels, cytosolic extracts were prepared and analyzed by immunoblotting with polyclonal antibodies against IκBα and IκBβ. The IκBα and IκBβ proteins were detected in CD4+ T cells preincubated with ALLN or PDTC for 60 min and followed by BCG treatment for different lengths of time (0, 30, 60, and 120 min), and neither IκBα nor IκBβ was reduced in the presence of inhibitors (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 2.

ALLN and PDTC inhibit expression of CD40L mRNA in BCG-activated CD4+ T cells. (A) ALLN (50 μM) or PDTC (100 μM) was added as indicated. The activation of CD4+ T cells was accomplished by treating cells with autologous APC infected with BCG, which were treated in advance with 50 μg of mitomycin C/ml. After incubation, total RNA was extracted from the different wells by using Trizol, reverse transcribed, and used for PCR. Control cultures without inhibitors were manipulated under the same conditions. The PCR products were separated in a 1% agarose gel and analyzed by staining with ethidium bromide. RNAs for CD40L and β-actin are shown from one representative of four experiments. +, present; −, absent. (B) The quantity of mRNA was determined by densitometer, with the result normalized to β-actin and expressed as a relative index.

FIG. 3.

Detection of IκBα and IκBβ in cell lysates by Western blotting. Cells were activated with APC infected with BCG for the indicated periods (A) or pretreated with ALLN or PDTC (B). Lysates were prepared as described in Materials and Methods and analyzed by an immunoblotting assay. Data are representatives of four independent experiments with similar results.

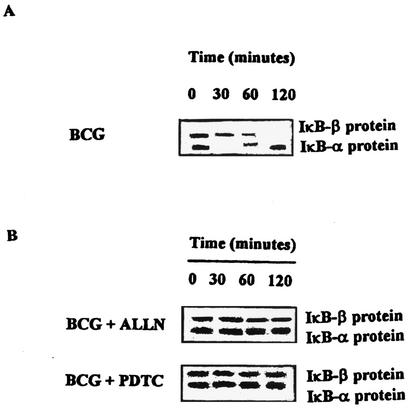

Activation with BCG results in increased transcription of the CD40L gene by a mechanism which is independent of protein synthesis.

We sought to determine whether or not transcriptional up-regulation of the CD40L gene is the predominant mechanism through which BCG induces CD40L expression in T cells. To test this, cells were cultured with or without 5 μgof Act D/mlto block CD40L gene transcription. After 1 h, cells were activated with APC infected with BCG or left nonactivated. Then cDNA was synthesized and analyzed by PCR withprimers specific for CD40L or β-actin. As shown in Fig. 4, treatment of cells with Act D completely abolished the ability of BCG to induce CD40L expression, indicating that CD40L expression in this system is dependent upon transcription. Next, we analyzed whether the transcriptional effect mediated by BCG was dependent on de novo protein synthesis. To this purpose,10 μg of CHX/mlwas added to cells for 1 h and cells subsequently activated with BCG. Following this, total RNA was extracted and CD40L mRNA levels were analyzed by RT-PCR. In Fig. 4,it may be observed that CD40L mRNA levels induced by BCG were not reduced by blocking protein synthesis with CHX, indicating that the positive effect of BCG on the CD40L gene expression was not dependent on de novo protein synthesis.

FIG. 4.

The transcriptional effect of BCG on the CD40L mRNA is independent of protein synthesis. (A) CD4+ T cells were cultured in medium alone or treated with 5 μg of Act D/ml or 10 μg of CHX/ml and then were activated with autologous APC infected with BCG at an MOI of 3. After incubation, cDNA was synthesized and analyzed by PCR with primers specific for CD40L or β-actin. The PCR products were separated in a 1% agarose gel and analyzed by staining with ethidium bromide. +, present; −, absent. (B) The histogram represents relative transcription rates, which were calculated after normalization to the respective β-actin signal. The experiment shown is one of five experiments performed.

BCG-induced CD40L expression is regulated via the PKC pathway.

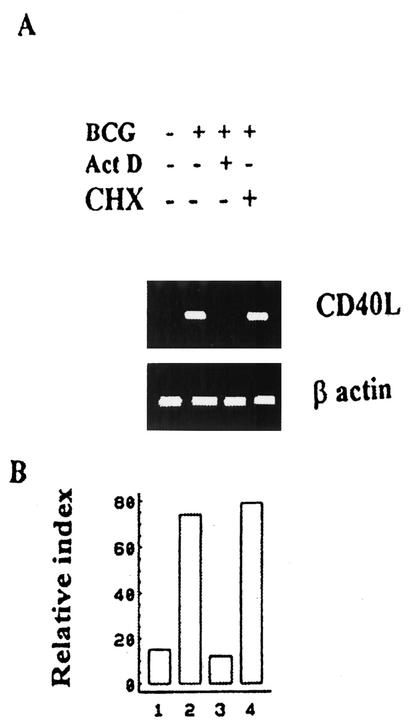

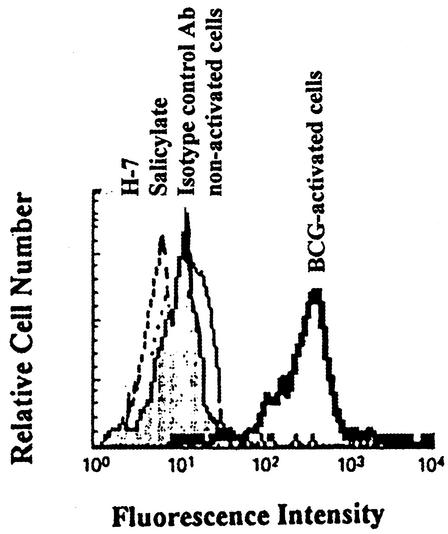

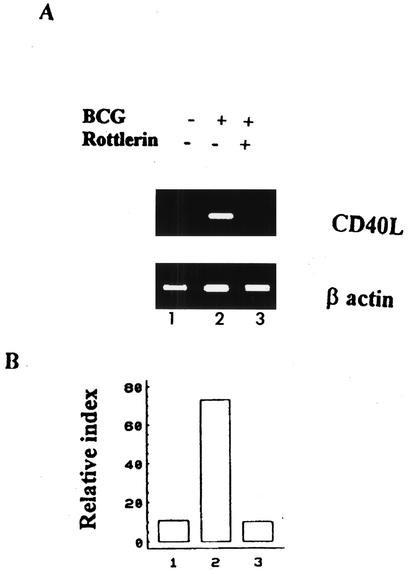

In order to determine the mechanism by which activation of NF-κB occurs, we tested the role of PKC in BCG-induced NF-κB activation by treating cells with the PKC antagonist H-7. Figure 5 indicates that BCG-activated cells showed significantly increased CD40L expression compared with that in control cells. However, BCG-activated cells treated with H-7 showed significant down-regulation (Fig. 5). Supporting the hypothesis that BCG induces phosphorylation of IκB via PKC to activate NF-κB. H-7-treated uninfected cells showed no significant change in CD40L expression compared with that in untreated cells (data not shown). Thus, H-7, which blocks phosphorylation of IκB and subsequent activation of NF-κB induced by BCG activation, also blocks resultant CD40L regulation. To confirm the role of NF-κB in regulating BCG-induced CD40L expression, cells were treated with salicylate or left untreated and then were activated with autologous APC infected with BCG at an MOI of 3 or left nonactivated for 24 h and labeled with antibody to CD40L. As shown in Fig. 5, BCG-activated cells showed significantly increased CD40L expression compared with that in uninfected control cells. However, BCG-activated cells treated with salicylate showed significant down-regulation (Fig. 5), confirming that BCG-induced activation of NF-κB and the up-regulation of CD40L are blocked by inhibiting the phosphorylation of IκB. In order to confirm the role of PKC in BCG-induced CD40L expression, we examined the effect of rottlerin (a Ca2+-independent PKC inhibitor which interferes with IκB kinase [IKK] activation) in our system. Figure 6 shows that the presence of rottlerin inhibited CD40L mRNA expression. These data suggest that Ca2+-independent PKC participate in the activation of IKK complexes by the T-cell receptor after recognition of BCG.

FIG. 5.

Down-regulation of CD40L expression on BCG-activated cells by the PKC inhibitor H-7 and salicylate. CD4+ T cells were cultured in medium alone or treated with 5 μM H-7 or 10 mM salicylate. After incubation, T cells were activated with autologous APC infected with BCG at an MOI of 3 or left nonactivated and analyzed by flow cytometry. One representative experiment of three is shown.

FIG. 6.

Rottlerin blocks BCG-mediated CD40L mRNA expression. (A) Total RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed from cells cultured with medium alone (lane 1) or activated with BCG alone (lane 2) or in combination with 10 μM rottlerin (lane 3) and analyzed by PCR. The PCR products were separated in a 1% agarose gel, and analyzed by staining with ethidium bromide. +, present; −, absent. (B) PhosphorImager quantification of results shown in panel A. Results shown were divided from ratios of CD40L to β-actin. The blot shown is a representative of 4 different experiments.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that NF-κB signaling pathways modulate the surface expression of CD40L on BCG-activated CD4+ T cells. Using specific pharmacologic inhibitors of NF-κB activation (ALLN and PDTC), down-regulation of CD40L protein levels was observed during T-cell activation by BCG. Consistent with these findings, T cells from NF-κB- and p50-deficient mice have reduced expression of CD40L, as did T cells from wild-type mice in the presence of proteasome inhibitors (34). These results were further supported by the fact that treatment of cells with ALLN and PDTC blocked the induction of CD40L gene expression in BCG-activated CD4+ T cells. It is important to note that IκBα and IκBβ protein production was not affected by the chemical protease inhibitors (Fig. 3B), indicating that our data are unlikely to be due to the effect of these chemical inhibitors on the level of expression of IκBα and IκBβ protein. On the other hand, we have not ruled out decreased mRNA stability in the presence of the inhibitors used. It has recently been reported that the stability pathway of CD40L mRNA decay is regulated in part by the formation of an activation-dependent ribonucleoprotein complex on a defined region of the CD40L mRNA (4). However, these agents both inhibit NF-κB, but they do so by distinct mechanisms. PDTC is a scavenger of free radicals, which interferes with the activation of genes requiring NF-κB, whereas ALLN is a specific inhibitor of the proteasome pathway, which prevents the degradation of IκB, thus keeping the IκB-NF-κB complex intact and preventing nuclear translocation of NF-κB. Moreover NF-κB is not known to increase mRNA stability (22). These results indicate that NF-κB activation is the critical signal for CD40L expression. A canonical NF-κB-binding site within the CD40L promoter has been identified (19). This site has been shown to be required for maximal induction of CD40L in human T cells after activation with anti-CD3 antibody. Whether this NF-κB-binding site is required by BCG remains to be elucidated.

We have demonstrated that the increase in CD40L in BCG-activated CD4+ T cells is abolished by the addition of Act D, which suggests that transcription of the CD40L gene is required for BCG-induced up-regulation of cell surface CD40L expression. Transcriptional regulation is a fundamental control mechanism in biological processes and requires the participation of several classes of proteins (28). Therefore, we investigated whether the transcriptional effect mediated by BCG was dependent on de novo protein synthesis. We have shown that CD40L mRNA induction, in CD4+ T cells activated with BCG, is not inhibited by CHX, indicating that de novo protein synthesis is not required for the induction of mRNA expression. At the same time, these results also suggest an important role of NF-κB-like transcription factors in this induction. Activation of NF-κB requires its dissociation from IκB (6, 10). A critical step in this process is the phosphorylation of IκB proteins, which then are degraded, resulting in the activation of NF-κB (36). In this study, salicylate, which also has been associated with down-regulation of NF-κB activation due to blocking the phosphorylation of IκB (18, 29), also blocked the functional activation of NF-κB in the BCG-activated CD4+ T cells, and it abolished the up-regulation of CD40L cell surface expression by BCG. This is further supported by our finding that the surface expression of CD40L was down-regulated in the presence of H-7, which blocks phosphorylation of IκB via PKC to inhibit NF-κB activation. These results suggest that the activation of PKC has a positive regulatory effect on CD40L gene expression by increasing the transcription in BCG-activated T cells. In contrast to our data, Nüsslein et al. (27) found that the PKC pathway is not the essential signal for the expression of CD40L in T cells. These apparently contradictory results are probably due to the stimulation of human T lymphocytes by different stimuli. Moreover, the requirement for PKC in the activation of the NF-κB cascade was further confirmed by the fact that treatment of CD4+ T cells with rottlerin, a Ca2+-independent PKC inhibitor which interferes in IKK activation, inhibits BCG-induced CD40L mRNA expression. These results are in agreement with the observation that mycobacterium-induced activation of NF-κB is inhibited by using a specific inhibitor of IKK (5). Although the importance of PKC in the activation of the NF-κB pathway in T lymphocytes has been recently demonstrated (8, 35), to our knowledge, this is the first evidence for BCG-induced association of PKC with the IKK complex in a physiologically relevant system. Since PKC family members includes the δ, ɛ, η, and θ isoenzymes (25), it remains to be elucidated which PKC isoenzyme is responsible for initiating the phosphorylation events. However, among the several PKC isoenzymes expressed in T cells, PKC-θ is unique in being rapidly recruited to the site of T cell receptor clustering. Therefore, it is possible that PKC-θ may play a role in IKK activation in our system.

Two main groups of transcription factors have been implicated in the expression of CD40L gene: NF-AT and NF-κB (33). Depending on the stimulus and system used, a role can be demonstrated for these transcription factors. Whether these transcription factors, separately or together, are required for BCG-induced human CD40L transcription remains to be determined.

In summary, these data show that PKC participates in NF-κB activation to increase the CD40L mRNA and protein levels in human T cells activated with BCG. Future directions should examine if these signaling pathways are found to be significant in host defense against M. tuberculosis infection.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Ruiz-Puente (Birmex) for providing the M. bovis BCG.

P.M.-S. is an EDI, COFAA, and SNI fellow. This work was financed in part by a Coordinación General de Posgrado e Investigación (CGPI) grant to P.M.-S.

REFERENCES

- 1.Armitage, R. J., C. R. Maliszewski, M. R. Alderson, K. H. Grabstein, M. K. Spriggs, and W. C. Fanslow. 1993. CD40L: a multi-functional ligand. Semin. Immunol. 5:401-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armitage, R. J., W. C. Fanslow, L. Strockbine, T. A. Sato, K. N. Clifford, B. M. Mcduff, D. M. Anderson, S. D. Gimpel, T. Davis-Smith, C. R. Maliszewski, E. A. Clark, C. A. Smith, K. H. Grabstein, D. Cosman, and M. K. Spriggs. 1992. Molecular and biological characterization of a murine ligand for CD40. Nature 357:80-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baeuerle, P., and T. Henkel. 1994. Function and activation of NF-kappa B in the immune system. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 12:141-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnhart, B., P. A. Kosinski, Z. Wang, G. S. Ford, M. Kiledjian, and L. R. Covey. 2000. Identification of a complex that binds to the CD154 3′ untranslated region: implications for a role in message stability during T cell activation. J. Immunol. 165:4478-4486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown, M. C., and S. M. Taffet. 1995. Lipoarabinomannans derived from different strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis differentially stimulate the activation of NF-κB and KBF1 in murine macrophages. Infect. Immun. 63:1960-1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng, J. D., R. P. Ryseck, R. M. Attar, D. Dambach, and R. Bravo. 1998. Functional redundancy of the nuclear factor κB inhibitors IκBα and IκBβ. J. Exp. Med. 188:1055-1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chomczynski, P., and N. Sacchi. 1987. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal. Biochem. 162:156-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coudronniere, N., M. Villalba, N. Englund, and A. Altman. 2000. NF-κB activation induced by T cell receptor/CD28 costimulation is mediated by protein kinase C-θ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:3394-3399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferlin, W. G., T. Vonderweid, F. Cottrez, D. A. Ferrick, R. L. Coffman, and M. C. Howard. 1998. The induction of a protective response in Leishmania major-infected BALB/c mice with anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody. Eur. J. Immunol. 28:525-531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finco, T. S., A. A. Beg, and A. S. Baldwin, Jr. 1994. Inducible phosphorylation of IκB-α is not sufficient for its dissociation from NF-κB and is inhibited by protease inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:11884-11888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghosh, S., M. J. May, and E. B. Kopp. 1998. NF-κB and REL proteins: evolutionarily conserved mediators of immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 16:225-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grewal, I. S., and R. A. Flavell. 1997. The CD40 ligand. At the center of the immune universe? Immunol. Res. 16:59-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grewal, I. S., and R. A. Flavell. 1996. A central role of CD40 ligand in the regulation of CD4+ T-cell responses. Immunol. Today 17:410-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grewal, I. S., and R. A. Flavell. 1998. CD40 and CD154 in cell-mediated immunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. Res. 16:111-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grewal, I. S., P. Borrow, E. G. Pamer, M. B. A. Oldstone, and R. A. Flavell. 1997. The CD40-CD154 system in anti-infective host defense. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 9:491-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gurunathan, S., K. R. Irvine, C. Y. Wu, J. I. Cohen, E. Thomas, C. Prussin, N. P. Restifo, and R. A. Seder. 1998. CD40 ligand trimer DNA enhances both humoral and cellular immune responses and induces protective immunity to infectious and tumor challenge. J. Immunol. 161:4563-4571. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kennedy, M. K., K. S. Picha, W. C. Fanslow, K. H. Grabstein, M. R. Alderson, K. N. Clifford, W. A. Chin, and K. M. Mohler. 1996. CD40/CD40 ligand interactions are required for T cell-dependent production of interleukin-12 by mouse macrophages. Eur. J. Immunol. 26:370-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kopp, E., and S. Ghosh. 1994. Inhibition of NF-κB by sodium salicylate and aspirin. Science 265:956-959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kunsch, C., S. M. Ruben, and C. A. Rosen. 1992. Selection of optimal kappa B/Rel DNA-binding motifs: interaction of both subunits of NF-kappa B with DNA is required for transcriptional activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:4412-4421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lederman, S., M. J. Yellin, A. Krichevsky, J. Belko, J. J. Lee, and L. Chess. 1992. Identification of a novel surface protein on activated CD4+ T cells that induces contact-dependent B cell differentiation (help). J. Exp. Med. 175:1091-1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee, B. O., L. Haynes, S. M. Eaton, S. L. Swain, and T. D. Randall. 2002. The biological outcome of CD40 signaling is dependent on the duration of CD40 ligand expression: reciprocal regulation by interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-12. J. Exp. Med. 196:693-704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindroos, P. M., A. B. Rice, Y. Z. Wang, and J. C. Bonner. 1998. Role of nuclear factor-kappa B and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways in IL-1 beta-mediated induction of alpha-PDGF receptor expression in rat pulmonary myofibroblasts. J. Immunol. 161:3463-3468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meyer, M., R. Schreck, and P. A. Baeuerle. 1993. H2O2 and antioxidants have opposite effects on activation of NF-κB and AP-1 in intact cells: AP-1 as secondary antioxidant-responsive factor. EMBO J. 12:2005-2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy, T. L., M. G. Cleveland, P. Kulesza, J. M. Magram, and K. M. Murphy. 1995. Regulation of interleukin-12 p40 expression through an NF-κB half-site. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:5258-5267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newton, A. C. 1997. Regulation of protein kinase C. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 9:161-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noelle, R. J. 1996. CD40 and its ligand in host defense. Immunity 4:415-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nüsslein, H. G., K. Frosch, W. Woith, P. Lane, J. Kalden, and B. Manger. 1996. Increase of intracellular calcium is the essential signal for the expression of CD40 ligand. Eur. J. Immunol. 26:846-850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perkins, N. 1995. Achieving transcriptional specificity with NF-κB. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 29:1433-1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pierce, J. W., M. A. Read, H. Ding, F. W. Luscinskas, and T. Collins. 1996. Salicylates inhibit IκB-α phosphorylation, endothelial-leukocyte adhesion molecule expression, and neutrophil transmigration. J. Immunol. 156:3961-3969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Read, M. A., A. S. Neish, F. W. Luscinskas, V. J. Palombella, T. Maniatis, and T. Collins. 1995. The proteasome pathway is required for cytokine-induced endothelial-leukocyte adhesion molecule expression. Immunity 2:493-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roy, M., A. Aruffo, J. A. Ledbetter, P. Linsley, M. Kehry, and R. J. Noelle. 1995. Studies on the independence of gp39 and B7 expression and function during antigen-specific immune responses. Eur. J. Immunol. 25:596-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roy, M., T. Waldschmidt, A. Aruffo, J. A. Ledbetter, and R. J. Noelle. 1993. The regulation of the expression of gp39, the CD40 ligand, on normal and cloned CD4+ T cells. J. Immunol. 151:2497-2510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schubert, L. A., G. King, R. Q. Cron, D. B. Lewis, A. Aruffo, and D. Hollenbaugh. 1995. The human gp39 promoter. Two distinct nuclear factors of activated T cell protein-binding elements contribute independently to transcriptional activation. J. Biol. Chem. 270:29624-29627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smiley, S. T., V. Csizmadia, W. Gao, L. A. Turka, and W. W. Hancock. 2000. Differential effects of cyclosporine A, methylprednisolone, mycophenolate, and rapamycin on CD154 induction and requirement for NF-kappaB: implication for tolerance induction. Transplantation 70:415-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun, Z., C. W. Arendt, W. Ellmeier, E. M. Schaeffer, M. J. Sunshine, L. Gandhi, J. Annes, D. Petrzilka, A. Kupfer, P. L. Schwartzberg, and D. R. Littman. 2000. PKC-θ is required for TCR-induced NF-κB activation in mature but not immature T lymphocytes. Nature 404:402-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thanos, D., and T. Maniatis. 1995. NF-κB: a lesson in family values. Cell 80:529-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Toossi, Z., B. D. Hamilton, M. H. Phillips, L. E. Averill, J. J. Ellner, and A. Salveker. 1997. Regulation of nuclear factor-kappa B and its inhibitor I kappa B-alpha/MAD-3 in monocytes by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and during human tuberculosis. J. Immunol. 15:4109-4116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tschou-Wong, K. M., O. Tanabe, C. Chi, T. A. Yie, and W. N. Rom. 1999. Activation of NF-κB in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-induced interleukin-2 receptor expression in mononuclear phagocytes. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 159:1323-1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsytsykova, A. V., E. N. Tsitsikov, and R. S. Geha. 1996. The CD40 L promoter contains nuclear factor of activated T cells-binding motifs which require AP-1 binding for activation of transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 271:3763-3770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verma, I. M., J. K. Stevenson, E. M. Schwarz, D. Van Antwerp, and S. Miyamoto. 1995. Rel/NF-kappa B/I kappa family: intimate tales of association and dissociation. Genes Dev. 9:2723-2735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wickremasinghe, M. I., L. H. Thomas, and J. S. Friedland. 1999. Pulmonary epithelial cells are a source of IL-8 in the response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis: essential role of IL-1 from infected monocytes in a NF-kappa B-dependent network. J. Immunol. 163:3936-3947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang, Y., M. Broser, and W. N. Rom. 1995. Activation of the interleukin 6 gene by Mycobacterium tuberculosis of lipopolysaccharide is mediated by nuclear factor NF-IL-6 and NF-kappa B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:2225-2229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]