Abstract

The emergence of circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV) strains in suboptimally vaccinated populations is a serious threat to the global poliovirus eradication. The genetic determinants for the transmissibility phenotype of polioviruses, and in particularly of cVDPV strains, are currently unknown. Here we describe the fecal excretion of wild-type poliovirus, oral polio vaccine, and cVDPV (Hispaniola) strains after intraperitoneal injection in poliovirus receptor-transgenic mice. Both the pattern and the level of fecal excretion of the cVDPV strains resemble those of wild-type poliovirus type 1. In contrast, very little poliovirus was present in the feces after oral polio vaccine administration. This mouse model will be helpful in elucidating the genetic determinants for the high fecal-oral transmission phenotype of cVDPV strains.

The global incidence of poliomyelitis has dropped spectacularly from an estimated 350.000 cases in 1988 to just 473 laboratory-confirmed cases in 2001 (6). This large decrease is due to the World Health Organization's coordinated vaccination programs using the oral polio vaccine (OPV). A rare side effect of the usage of OPV is the so-called vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis (VAPP). VAPP is a rare event (0.5 cases per 1 million first-time OPV doses), which occurs among first-time OPV recipients and contacts of first-time OPV recipients in roughly equal frequencies (16). Molecular analysis of the composition of the poliovirus strains causing VAPP revealed that the attenuating mutations are lost by the accumulation of specific point mutations, either alone or in combination with intertypic recombination between the three strains from the trivalent OPV vaccine (9, 12). Molecular analysis of a large panel of VAPP strains indicated that recombination of the OPV strains was not restricted to poliovirus strains but could also involve nonpoliovirus enteroviruses (NPEV) (13). Direct proof for the natural occurrence of such recombination events came from the molecular analysis of the strains causing a poliomyelitis epidemic on the island Hispaniola. Sequence alignments of the poliovirus serotype 1 isolates of this outbreak revealed that they contained the nonstructural protein-encoding part of the genome from a nonpoliovirus enterovirus and that multiple NPEV strains had acted as donors for these sequences (14).

The reversion of specific nucleotide and amino acids mutations present in the Sabin 1 derivatives of the wild-type polioviruses results in an increase in virulence (for a review, see reference 15). The danger of vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV) for the polio eradication campaign is, however, not primarily determined by its high-neurovirulence phenotype. It is the transmissibility phenotype of reverted poliovirus vaccine strains that poses the greatest risk to global poliovirus eradication. OPV strains have a low basic reproduction number (R0), although it is estimated that R0 is >1, meaning that these vaccine strains will circulate in a fully susceptible population (11). Vaccine-derived strains with an increased transmissibility will persist in a suboptimally vaccinated population when the effective reproduction rate (Rn) is >1. Such vaccine-derived strains have indeed been recovered from sewage (19) and from a patient with acute flaccid paralysis (7). During long-term circulation of vaccine-derived poliovirus strains, quasispecies will arise with an increased transmissibility and neurovirulence. In recent years several such strains, which have a substantial genetic drift (mutations) and shift (recombination with poliovirus or nonpoliovirus enteroviruses), have emerged. These genetic differences reflect the long-term transmission of VDPV strains in the suboptimally vaccinated populations of Egypt (4), Hispaniola (2), the Philippines (3), and Madagascar (5). Such OPV-derived strains, which possess both a high transmissibility and a high neurovirulence, are referred to as circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV) strains. Currently it is unclear what the correlation between the transmissibility and the neurovirulence phenotype is, i.e., whether all highly neurovirulent strains are also highly transmissible and whether all highly transmissible strains possess a high neurovirulence.

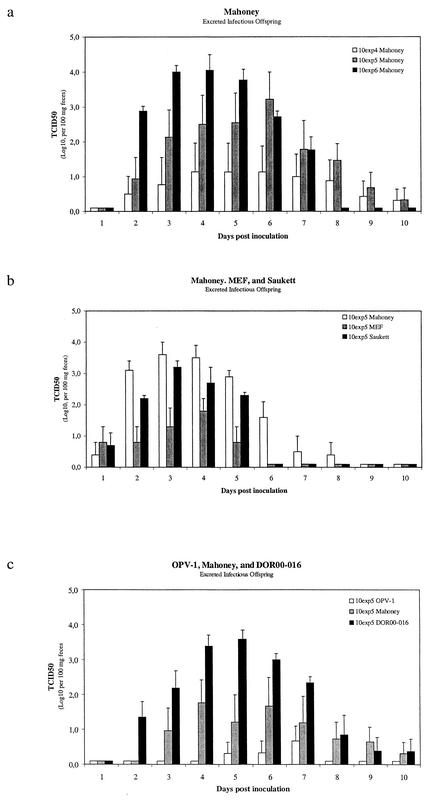

The lack of knowledge concerning genetic determinants of person-to-person transmissibility hampers the risk assessment of the isolated vaccine-derived poliovirus strains for the global poliovirus eradication. It is therefore important to develop ways to assess the transmissibility of naturally occurring and (artificially generated) vaccine-derived poliovirus strains. Recently it has been shown that mice who possess the human receptor for poliovirus (ICR-PRVTg21 mice [10]) excreted poliovirus in the feces after intraperitoneal injection (1). As fecal excretion is one of the main determinants for high transmissibility of picornaviruses, we have used these mice to analyze the fecal excretion pattern of the Sabin OPV strains (OPV-1, OPV-2, and OPV-3), as well as three representative wild-type strains (Mahoney, MEF, and Saukett), and three representative strains of the Hispaniola outbreak (DOR00-016, HAI00-03, and HAI01-07) (14). All viruses were amplified on Hep-2C cells, concentrated by Amicon (Millipore) filtration (cutoff, 100.000 kDa), and purified by CsCl gradient centrifugation and gel filtration (PD-10; Pharmacia). Threefold serial dilutions in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were made, and the 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) of each dilution was determined on Hep-2C cells (17). Groups (n = 6) of ICR-PVRTg21 mice, with ages between 7 and 12 weeks, were housed in separate isolators. Each mouse was kept in its own cage. Groups had on average an equal distribution of male and female animals. After intraperitoneal injection of poliovirus in 0.2 ml of PBS, the mice were monitored daily, and fecal samples of individual mice were collected daily up to 10 days postinoculation (p.i.). Feces were resuspended by vortexing in 10 volumes of PBS and 1 volume of chloroform. After centrifugation (1,800 × g for 10 min), the poliovirus titer in the supernatant of each fecal sample was determined and expressed as TCID50 per 100 mg of feces (Fig. 1). Subsequently, we determined the number of poliovirus-excreting mice, the mean duration of excretion, and the mean poliovirus level in the positive fecal samples (Table 1). Furthermore, we determined the relative level of duration of excretion by calculation of the poliovirus excretion days coefficient (PEDC), which we defined as the number of virus-positive fecal samples (from days 2 to 6 p.i.) divided by the total number of fecal samples (from days 2 to 6 p.i.) per group of mice (Table 1). The reason for focusing on days 2 to 6 p.i. is that peak excretion occurred in this period (Fig. 1), although occasionally a mouse excreted poliovirus for a longer period (up to and most likely beyond day 10 p.i.). Analysis of the excretion data of male (n = 17) versus female (n = 16) mice receiving 105 TCID50 (Mahoney) showed no gender-related differences in the duration or level of poliovirus excretion (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

The group average TCID50 of poliovirus in the feces of individual mice (six ICR-PVRTg21 mice per group) was determined at days 1 to 10 following intraperitoneal injection of different strains and concentrations of poliovirus. Data of representative experiments are shown. (a) Wild-type serotype 1 (Mahoney) was given at a TCID50 of 104, 105, and 106. (b) Intermediate doses (TCID50 = 105) of the three different serotypes of wild-type poliovirus strains. (c) Intermediate doses (TCID50 = 105) of three serotype 1 strains: a vaccine (OPV-1) strain, a wild-type (Mahoney) strain, and a cVDPV (DOR00-016) strain. The detection level of poliovirus in the individual fecal samples is at a TCID50 of 101.8, and the error bars represent the standard errors of the means.

TABLE 1.

Results of poliovirus inoculation assays

| TCID50a | Virus (serotype) | Phenotype | No. of poliovirus-excreting mice/total no. injectedb | Mean (SD) excretion duration (days)c | Mean (SD) poliovirus excretion (log10 TCID50/100 mg of feces) | Mean PEDC (SD)d | No. of positive mice/no. inoculated (S/P; SD) at day 10 p.i.e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 103 | Mahoney (1) | Wild type | 0/6 | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0/6 | |

| 104 | Mahoney | Wild type | 2/6 | 2.2 (3.4) | 3.1 (1.1) | 0.3 (0.4) | 2/6 (0.8; 0.4) |

| 105 | OPV-1 (1) | Vaccine | 3/12 | 0.4 (0.8) | 2.0 (0.2) | 0.0 (0.1) | 2/12 (0.4; 0.2) |

| Mahoney | Wild type | 27/30 | 4.3 (2.1) | 3.0 (0.8) | 0.7 (0.3) | 19/27 (0.7; 0.3) | |

| DOR00-016 (1) | cVDPV | 12/12 | 5.1 (1.3) | 2.8 (0.7) | 0.9 (0.2) | 7/11 (0.7; 0.3) | |

| MEF (2) | Wild type | 5/6 | 2.0 (1.7) | 2.4 (0.3) | 0.4 (0.3) | NDf | |

| OPV-3 (3) | Vaccine | 0/16 | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | ND | ||

| Saukett (3) | Wild type | 6/6 | 3.8 (0.4) | 2.7 (0.6) | 0.8 (0.1) | ND | |

| 106 | Mahoney | Wild type | 14/14 | 5.1 (1.0) | 3.2 (0.8) | 0.9 (0.1) | 9/9 (0.9; 0.1) |

| DOR00-016 | cVDPV | 5/6 | 5.3 (2.8) | 3.5 (0.8) | 0.8 (0.4) | 4/5 (0.9; 0.1) | |

| HAI00-003 (1) | cVDPV | 6/6 | 4.8 (1.6) | 3.3 (0.9) | 0.8 (0.4) | 4/5 (0.6; 0.4) | |

| HAI01-007 (1) | cVDPV | 6/6 | 5.5 (0.5) | 3.3 (0.9) | 1.0 (0.1) | 5/5 (0.5; 0.2) | |

| 107 | OPV-1 | Vaccine | 1/9 | 0.1 (0.3) | 1.9 | 0.0 (0.1) | 8/8 (0.3; 0.1) |

| 108 | OPV-1 | Vaccine | 5/14 | 0.7 (1.2) | 2.3 (0.5) | 0.1 (0.2) | 13/13 (0.7; 0.2) |

| OPV-2 (2) | Vaccine | 1/10 | 0.1 (0.4) | 2.8 | 0.0 (0.0) | ND | |

| OPV-3 | Vaccine | 3/10 | 1.0 (1.4) | 2.0 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.2) | ND |

Injected intraperitoneally with 200 μl of PBS.

Mice that had at least one poliovirus-positive fecal sample between days 2 and 10 p.i. were considered poliovirus excreting. Up to four groups of mice (n = 6 to 10) were used per experiment. The data in this table are based upon multiple experiments in cases where n was >10.

The results of day 1 have been omitted from this analysis, as we frequently observed shedding of the inoculum after intraperitoneal injection of high doses (e.g., TCID50 = 108) of OPV (data not shown).

PEDC of mice receiving the same poliovirus (at least six mice per group).

A mouse was considered positive when S/P was > 0.1.

ND, not determined.

The duration of excretion of poliovirus showed a strong dose-response relation, as shown by poliovirus titers in the feces of mice inoculated with different concentrations of wild-type serotype 1 (Mahoney). Intraperitoneal injection of 103 TCID50 of Mahoney did not result in detectable amounts (TCID50 > 101.8) of poliovirus in the feces, while a 10-fold increase (TCID50 = 104) of the inoculation titer resulted in excretion of poliovirus between days 2 and 10 p.i. in two of the six injected mice (Fig. 1a and Table 1). The duration of poliovirus excretion was considerably longer when 105 TCID50 of Mahoney was administered, although still one of the six animals did not excrete poliovirus at all (Fig. 1a and Table 1). When 106 TCID50 of Mahoney was administered, all animals excreted virus (up to a TCID50 of 105.8 per 100 mg of feces) and occasionally a mouse died at 5 to 9 days p.i. The mean level of poliovirus in the positive samples, in contrast, did not show a dose-response relation, as mean TCID50 levels were around 103 TCID50 per 100 mg of feces, irrespective of the inoculation dose (Table 1). Although the representative wild-type strains for the three different serotypes of poliovirus all showed the same excretion pattern, it is clear that both the duration and the level of MEF (serotype 2) excretion are reduced in comparison with those of Mahoney and Saukett (serotype 3) (Fig. 1b and Table 1).

Next, we compared the excretion level and pattern of DOR00-016, a representative cVDPV strain of the largest genogroup of the Hispaniola outbreak (14), with the excretion of OPV-1 and the wild-type serotype 1 strain (Mahoney). Both the duration and the level of fecal excretion of the DOR00-016 strain mimicked those of the Mahoney strain after inoculation of 105 TCID50 (Fig. 1c). The differences in the PEDCs of DOR00-016 (PEDC = 0.8) and Mahoney (PEDC = 1.0) observed after injection of a TCID50 of 106 result from the fact that one of the six mice receiving DOR00-016 did not respond (no virus excretion during the entire monitoring period and no serotype 1-specific immunoglobulin G [IgG] antibodies). When representative strains of the two other genogroups of the Hispaniola outbreak (HAI0-003 and HAI01-007) were inoculated at a TCID50 of 106, all mice excreted poliovirus for comparable durations.

Blood samples of all mice were taken just before euthanasia at 10 days p.i., and serotype-specific poliovirus IgG levels were determined after a 1:50 dilution of the serum, as described before (1). The relative level of poliovirus type 1-specific antibodies was expressed as the ratio of the optical density at 405 nm (OD405) of the sample (S) to that of the positive control (P), where we considered an S/P of >0.1 to be positive (Table 1). We found an almost perfect correlation between the level of virus excretion during the 10-day observation period (74 positive) and the presence of an IgG titer at 10 days p.i. (68 positive) after the inoculation of wild-type (or wild-type-like) poliovirus strains. However, when OPV strains were inoculated at high titers, we observed hardly any fecal excretion, whereas a high IgG titer was found (Table 1 and data not shown). Mice that did not develop an IgG titer excreted virus for shorter periods (i.e., PEDC of 0.4 with a standard deviation [SD] of 0.3 versus a PEDC of 0.9 with an SD of 0.2). In general, the level of IgG-specific antibodies was higher after inoculation with a higher dose, although relatively large differences were found among mice receiving the same poliovirus strain and dose (Table 1). This high difference in response to the same inoculum and the fact that OPV-1 induces intermediate to high IgG titers in mice that do not excrete virus excludes the use of this parameter to predict the fecal excretion level and the duration of excretion of different (vaccine-derived) polioviruses.

The global eradication of the highly contagious wild-type poliovirus is a big challenge for mankind. The recent identification of circulating OPV-derived strains, which combine a high neurovirulence with a high transmissibility, in suboptimally vaccinated populations (2-5), is a major threat to this eradication. The lack of knowledge concerning the genetic determinants for the high-transmissibility phenotype hampers a proper risk assessment of the use of trivalent OPV in comparison to divalent or monovalent OPV or inactivated polio vaccine. Also, the range of potential NPEV strains, which can act as donor sequences for cVDPV strains, will remain unknown as long as the genetic determinants of transmissibility have not been characterized in more detail.

Unfortunately, the resistance to oral infection of poliovirus receptor (PVR) transgenic mice prohibits a direct analysis of the difference in transmissibility (R0 or Rn) of poliovirus strains in a mouse population. Although several different promoters for the expression of the PVR in transgenic mice have been used (i.e., the promoter of PVR itself [18], the rat intestine fatty acid binding protein [20], and the human β-actin protein [8]), none of these transgenic mice can be infected with poliovirus by the oral route. For this reason we have analyzed the fecal excretion of different poliovirus strains in transgenic mice after intraperitoneal injection, as the total excretion amount of virus is one of the major determinants of transmissibility of picornaviruses.

We observed large differences between the excretion of the OPV vaccine strains on one hand and that of the cVDPV and wild-type strains on the other hand. The combination of mutations and recombinations of the Hispaniola strains is apparently sufficient to turn the low fecal excretion phenotype of OPV into one which is indistinguishable from that of the wild-type poliovirus. We expect to achieve further insight in the poliovirus transmissibility determinants by analyzing in vitro-generated site-directed mutagenized and recombinant polioviruses in our PVR mouse fecal excretion model.

Acknowledgments

The technical assistance of Femke van Nunen, Rutger Schepp, and Femke van den Berg in preparing the poliovirus stocks and performance of the titrations is greatly appreciated. We thank Harrie van der Avoort for helpful discussions and for critically reading the manuscript and Olen Kew (CDC) for providing the Hispaniola strains.

This work was supported by a grant from the Prinses Beatrix Fonds (The Netherlands).

REFERENCES

- 1.Buisman, A. M., J. A. Sonsma, T. G. Kimman, and M. P. Koopmans. 2000. Mucosal and systemic immunity against poliovirus in mice transgenic for the poliovirus receptor: the poliovirus receptor is necessary for a virus-specific mucosal IgA response. J. Infect. Dis. 181:815-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2000. Outbreak of poliomyelitis-Dominican Republic and Haiti, 2000. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 49:1094-1103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2001. Acute flaccid paralysis associated with circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus-Philippines, 2001. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 50:874-875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2001. Circulation of a type 2 vaccine-derived poliovirus-Egypt, 1982-1993. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 50:41-42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2002. Poliomyelitis-Madagascar, 2002. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 51:662. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2002. Progress toward global eradication of poliomyelitis, 2001. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 51:253-256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cherkasova, E. A., E. A. Korotkova, M. L. Yakovenko, O. E. Ivanova, T. P. Eremeeva, K. M. Chumakov, and V. I. Agol. 2002. Long-term circulation of vaccine-derived poliovirus that causes paralytic disease. J. Virol. 76:6791-6799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crotty, S., L. Hix, L. J. Sigal, and R. Andino. 2002. Poliovirus pathogenesis in a new poliovirus receptor transgenic mouse model: age-dependent paralysis and a mucosal route of infection. J. Gen. Virol. 83:1707-1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cuervo, N. S., S. Guillot, N. Romanenkova, M. Combiescu, A. Aubert-Combiescu, M. Seghier, V. Caro, R. Crainic, and F. Delpeyroux. 2001. Genomic features of intertypic recombinant Sabin poliovirus strains excreted by primary vaccinees. J. Virol. 75:5740-5751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dowdle, W. R. 2001. Polio eradication: turning the dream into reality. ASM News 67:397-402. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fine, P. E., and I. A. Carneiro. 1999. Transmissibility and persistence of oral polio vaccine viruses: implications for the global poliomyelitis eradication initiative. Am. J. Epidemiol. 150:1001-1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furione, M., S. Guillot, D. Otelea, J. Balanant, A. Candrea, and R. Crainic. 1993. Polioviruses with natural recombinant genomes isolated from vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis. Virology 196:199-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guillot, S., V. Caro, N. Cuervo, E. Korotkova, M. Combiescu, A. Persu, A. Aubert-Combiescu, F. Delpeyroux, and R. Crainic. 2000. Natural genetic exchanges between vaccine and wild poliovirus strains in humans. J. Virol. 74:8434-8443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kew, O., V. Morris-Glasgow, M. Landaverde, C. Burns, J. Shaw, Z. Garib, J. Andre, E. Blackman, C. J. Freeman, J. Jorba, R. Sutter, G. Tambini, L. Venczel, C. Pedreira, F. Laender, H. Shimizu, T. Yoneyama, T. Miyamura, H. van Der Avoort, M. S. Oberste, D. Kilpatrick, S. Cochi, M. Pallansch, and C. de Quadros. 2002. Outbreak of poliomyelitis in Hispaniola associated with circulating type 1 vaccine-derived poliovirus. Science 296:356-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minor, P. D. 1993. Attenuation and reversion of the Sabin vaccine strains of poliovirus. Dev. Biol. Stand. 78:17-26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nkowane, B. M., S. G. Wassilak, W. A. Orenstein, K. J. Bart, L. B. Schonberger, A. R. Hinman, and O. M. Kew. 1987. Vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis. United States: 1973 through 1984. JAMA 257:1335-1340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reed, L. J., and H. Muench. 1938. A simple method of estimating fifty per cent end points. Am. J. Hygiene 27:493-497. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ren, R. B., F. Costantini, E. J. Gorgacz, J. J. Lee, and V. R. Racaniello. 1990. Transgenic mice expressing a human poliovirus receptor: a new model for poliomyelitis. Cell 63:353-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shulman, L. M., Y. Manor, R. Handsher, F. Delpeyroux, M. J. McDonough, T. Halmut, I. Silberstein, J. Alfandari, J. Quay, T. Fisher, J. Robinov, O. M. Kew, R. Crainic, and E. Mendelson. 2000. Molecular and antigenic characterization of a highly evolved derivative of the type 2 oral poliovaccine strain isolated from sewage in Israel. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3729-3734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang, S., and V. R. Racaniello. 1997. Expression of the poliovirus receptor in intestinal epithelial cells is not sufficient to permit poliovirus replication in the mouse gut. J. Virol. 71:4915-4920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]