Abstract

In eukaryotic cells, CLS (cardiolipin synthase) is involved in the final step of cardiolipin synthesis by catalysing the transfer of a phosphatidyl residue from CDP-DAG (diacylglycerol) to PG (phosphatidylglycerol). Despite an important role of cardiolipin in regulating mitochondrial function, a gene encoding the mammalian CLS has not been identified so far. We report in the present study the identification and characterization of a human cDNA encoding the first mammalian CLS [hCLS1 (human CLS1)]. The predicted hCLS1 peptide sequence shares significant homology with the yeast and plant CLS proteins. The recombinant hCLS1 enzyme expressed in COS-7 cells catalysed efficiently the synthesis of cardiolipin in vitro using CDP-DAG and PG as substrates. Furthermore, overexpression of hCLS1 cDNA in COS-7 cells resulted in a significant increase in cardiolipin synthesis in intact COS-7 cells without any significant effects on the activity of the endogenous phosphatidylglycerophosphate synthase of the transfected COS-7 cells. Immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated that the recombinant hCLS1 protein was localized to the mitochondria when transiently expressed in COS-7 cells, which was further corroborated by results from subcellular fractionation analyses of the recombinant hCLS1 protein. Northern-blot analysis showed that the hCLS1 gene was predominantly expressed in tissues that require high levels of mitochondrial activities for energy metabolism, with the highest expression in skeletal and cardiac muscles. High levels of hCLS1 expression were also detected in liver, pancreas, kidney and small intestine, implying a functional role of hCLS1 in these tissues.

Keywords: acyltransferase, human cardiolipin synthase 1 (hCLS1), lysocardiolipin, lysophosphatidylglycerol, mitochondria, phospholipid

Abbreviations: ALCAT1, acyl-CoA:lysocardiolipin acyltransferase-1; CHO cell, Chinese-hamster ovary cell; CLS, cardiolipin synthase; DAG, diacylglycerol; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; hCLS, human CLS; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; LPG, lysophosphatidylglycerol; LPGAT1, lysophosphatidylglycerol acyltransferase-1; PG, phosphatidylglycerol; PGP, phosphatidylglycerophosphate; PGS, PGP synthase; poly(A)+, polyadenylated

INTRODUCTION

Cardiolipin, also termed diphosphatidylglycerol, represents a unique dimeric phospholipid which consists of four fatty acyl chains that are 14–18 carbon atoms in length. The pattern of the fatty acyl chains varies among biological species, and is almost exclusively restricted to polyunsaturated fatty acids with 18 carbon atoms in animals and higher plants. Cardiolipin is predominantly located in the energy-transducing membranes of the mitochondria in eukaryotic cells. Biologically, cardiolipin plays a pivotal role in the structure and function of mitochondria [1,2]. Cardiolipin is required for the reconstituted activity of a number of metabolic enzymes and carrier proteins involved in oxidative phosphorylation in the mitochondria [3]. Cardiolipin in the inner mitochondrial membrane serves as a Ca2+-binding site, through which Ca2+ triggers mitochondrial membrane permeabilization [4]. Cardiolipin also plays a role in maintaining the mitochondrial membrane potential, osmotic stability of mitochondrial membranes and protein import [3]. Additionally, cardiolipin is required for cell survival, and disassociation of cytochrome c from cardiolipin triggers apoptosis [5,6]. Consequently, cardiolipin deficiency caused by mutations of the yeast CRD1 (cardiolipin synthase) gene encoding a CLS (cardiolipin synthase) results in impaired viability, decreased mitochondrial membrane potential and defective oxidative phosphorylation [7–10]. Similarly, cardiolipin deficiency in CHO cells (Chinese-hamster ovary cells) results in morphological and functional mitochondrial abnormalities, manifested by more stringent temperature-sensitivity for cell growth in glucose-deficient medium and by decreased ATP production [11]. The mutant CHO cells demonstrate an increased glycolysis, reduced oxygen consumption and defective respiratory electron transport chain activity [11].

In eukaryotic mitochondria, cardiolipin is synthesized by three consecutive steps that begins with the generation of PG (phosphatidylglycerol) from CDP-DAG (diacylglycerol) [3]. CDPDAG is formed from phosphatidic acid catalysed by phosphatidic acid:CTP cytidylyltransferase and then converted into PG through the sequential enzymatic actions of PGS [PGP (phosphatidylglycerophosphate) synthase] and PGP phosphatase [3,12]. The committed and rate-limiting step in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is catalysed by PGS [13]. The final step of cardiolipin synthesis involves transfer of a phosphatidyl residue from CDP-DAG to PG, which is catalysed by CLS [14]. The alternative cardiolipin biosynthetic pathway involves acylation of lysophospholipids in the ER (endoplasmic reticulum). We have recently identified two acyltransferases involved in the synthesis of cardiolipin in ER. One is an LPGAT (lysophosphatidylglycerol acyltransferase) (LPGAT1) that catalyses acylation of LPG (lysophosphatidylglycerol) to produce PG [15], whereas the other is an ALCAT (acyl-CoA:lysocardiolipin acyltransferase; ALCAT1) that catalyses the acylation of lysocardiolipin to cardiolipin [16]. The identification of LPGAT1 and ALCAT1 suggests that ER plays an important role in cardiolipin biosynthesis, although it remains elusive whether a complete cardiolipin biosynthetic pathway exists in the ER.

Cardiolipin is one of the principal phospholipids in the mammalian heart, a tissue that has perpetually high energy demands. Consequently, cardiolipin deficiency in ischaemia and reperfusion results in mitochondrial dysfunction manifested by a decrease in oxidative capacity, loss of cytochrome c and generation of reactive oxygen species [17–19]. Cardiolipin, but not the peroxidized form, was able to almost completely restore the loss of cytochrome c oxidase activity caused by reactive oxygen species [19]. Decreased cardiolipin synthesis was associated with cytochrome c release in palmitate-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis [20]. Additionally, both the levels of cardiolipin and its lipid composition were profoundly altered by thyroid hormone, a major regulator of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. Consequently, thyroid hormone treatment resulted in a significant increase in cardiolipin content, accompanied by an increased CLS activity [12,21]. Furthermore, cardiolipin is a potent inhibitor of ceramide synthase, and a decrease in cardiolipin has been shown to increase the production of ceramide [22], one of the major regulators of insulin resistance in diabetes [23]. Hence, endurance training that is known to improve insulin-sensitivity has been shown to increase cardiolipin content in skeletal muscle [24]. Finally, decreased levels of cardiolipin may contribute to mitochondrial decay associated with aging [25].

Despite an important role of cardiolipin in regulating mitochondrial function in mammalian tissues, as well as its potential involvement in metabolic diseases, a gene encoding the mammalian CLS has not been identified so far. Previously, a 50 kDa CLS has been purified to near-homogeneity from rat liver [26], yet the gene coding for the enzyme remains elusive. As part of our continued efforts in identifying novel enzymes involved in phospholipid synthesis, we report here the identification and characterization of a cDNA encoding an hCLS (human CLS; hCLS1). The hCLS1 cDNA was identified from its predicted sequence homology to yeast CLS. Our results showed that overexpression of the hCLS1 cDNA in COS-7 cells resulted in significant increases in CLS activity in vitro and cardiolipin biosynthesis in intact COS-7 cells. The functional importance of hCLS1 in cardiolipin synthesis was further corroborated by its subcellular localization in mitochondria as well as its expression profile in human tissues that require high level of mitochondrial content for their physiological functions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The full-length hCLS cDNA clone

A 1.2 kb cDNA clone encoding a putative hCLS enzyme was initially identified from the NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) genomic database (accession no. AF241784) based on its peptide sequence homology to the yeast CLS, and was then cloned by PCR amplification using primers designed from the predicted coding region and cDNA library from human liver (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA, U.S.A.). A FLAG-tagged version of hCLS1 was engineered by PCR amplification with Pfu DNA polymerase using a primer pair (forward, 5′-GCCACCATGGATTACAAGGATGACGACGATAAGTAGCCTTGCGCGTGGCGCGCG-3′, and reverse, 5′-TAACAGTGAGGGATGACTTTCA-3′), designed to add a FLAG tag to the N-terminus of hCLS1, and a thermal cycling condition of 32 cycles (94 °C for 30 s, 56 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 2 min). The amplified 1.0 kb DNA fragment was subcloned into the SrfI site of PCR-script Amp SK(+) vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, U.S.A.) and verified by DNA sequencing.

Northern-blot analysis

To determine the tissue distribution pattern of hCLS1 mRNA expression, multiple human tissue poly(A)+ (polyadenylated) RNA blots (Clontech) were hybridized with [α-32P]dCTP (3000 Ci/mmol; ICN Radiochemicals)-labelled full-length cDNA of the hCLS1 gene using a Prime-It RmT Random Primer Labeling kit (Stratagene). Hybridization was performed in ULTRAHyb (Ambion, Austin, TX, U.S.A.) at 55 °C overnight, followed by washing three times at 55 °C in 2× SSC buffer (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl and 0.015 M sodium citrate) containing 0.1% SDS and 1 mM EDTA. The blots were stripped with boiling 1% SDS to remove radiolabelled probe and then reprobed with radiolabelled human β-actin and GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) cDNAs as internal controls for mRNA loading. The blots were exposed to a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics) screen to visualize signals and were quantified by ImageQuant (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, U.S.A.).

Expression of hCLS1, LPGAT1 and ALCAT1 in mammalian cells

The hCLS1 cDNA insert of the PCR-script Amp SK(+) vector was subcloned into the EcoRV and NotI sites of pcDNA3.1(+) vector (Invitrogen) for transient expression in COS-7 cells. COS-7 cells were maintained under the conditions recommended by the American Tissue Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, U.S.A.). Two million cells were subcultured, 1 day before transfection, on to a 100 mm×20 mm plate, resulting in approx. 70% confluence. The cells were either transfected with 10 μg each of the LPGAT1 and ALCAT1 expression vectors [15,16] or co-transfected with 10 μg of the LPGAT1 expression plasmid plus 10 μg of the hCLS1 expression plasmid respectively, using FuGENE 6™ (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, U.S.A.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were washed once with ice-cold PBS 48 h after the transfection, and pelleted by centrifugation. The cell pellets were homogenized in a lysis buffer that contains 1% Triton X-100 in PBS and 1×Complete™ protease inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics). The resultant homogenates were used to assess the activity of CLS or the PGS activity of the transfected COS-7 cells. The protein concentration in homogenates was determined by a BCA (bicinchoninic acid) protein assay kit (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

In vitro assays for CLS activity

CLS activity was assayed in a reaction mixture of 200 μl containing 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.0), 4.0 mM MgCl2, 20 μM [14C]oleoyl-CoA (50 mCi/mmol; American Radiolabeled Chemicals, St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.), 2.0 mM LPG {1-oleoyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-[phospho-rac-(1-glycerol)]} and 2.0 mM CDP-DAG (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL, U.S.A.). The reaction was initiated by the addition of 50 μg of cell homogenates that contained recombinant hCLS1 transiently expressed in COS-7 cells and incubated for 20 min at 30 °C in the presence or absence of the recombinant LPGAT1 protein. The recombinant LPGAT1 was used to generate [14C]PG that was not commercially available. As a positive control for the detection of radiolabelled cardiolipin, recombinant ACLAT1 was used to catalyse the synthesis of [14C]cardiolipin with monolysocardiolipin (Avanti Polar Lipids) and [14C]acyl-CoA as substrates as previously described [16]. The reactions were terminated by adding 1 ml of chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v), followed by addition of 0.4 ml of 0.9% KCl to facilitate phase separation. After vigorous vortex-mixing for 10 s to extract lipids, a brief centrifugation was performed. Aliquots of the organic phase containing phospholipids were collected, dried under a N2 stream and separated by the Liner-K Preadsorbent TLC plate (Waterman, Clifton, NJ, U.S.A.) with chloroform/methanol/water (65:25:4, by vol.) as the developing solvent. The products were visualized by a phosphoimager (Amersham Biosciences) and quantified by ImageQuant.

In vitro assays for PGS activity

PGS activity was assayed at 37 °C for 30 min in a 200 μl reaction mixture containing 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.4), 0.25 mM CDP-DAG, 0.1 mM [14C]glycerol-3-phosphate (American Radiolabeled Chemicals) and 50 mg of cell lysate protein from COS-7 cells transiently transfected with either empty vector (control), the LPGAT1 expression vector or the ALCAT1 expression vector, or co-transfected with both LPGAT1 and hCLS1 expression vectors respectively. The lipid products were extracted and subjected to TLC analysis as previously described [13].

Analysis of CLS activity of hCLS1 in intact COS-7 cells

COS-7 cells were transfected with 2.0 μg of LPGAT1-encoding plasmid and various amounts of hCLS1-encoding plasmid (0–4.5 μg) using FuGENE 6™ (Roche Diagnostics) following the manufacturer's instructions. [14C]Oleoyl-CoA was added to the culture medium, 24 h after the transfection, at a final concentration of 0.16 mM to label newly synthesized lipids. After 24 h labelling, the cells were rinsed twice with ice-cold PBS and were subjected to lipid extraction and TLC analyses as described above.

Subcellular fractionation analysis

Subcellular fractionation analysis was carried out to localize hCLS1 transiently expressed in COS-7 cells using a previously described method [15].

Immunocytohistochemistry

Cells were grown and transfected on a chamber culture slide (BD Bioscience). Cells were incubated, 48 h after transfection, in the complete medium containing 100 nM MitoTracker Red CMXRos for 10 min at 37 °C to gain the specific staining for mitochondria. The cells were then washed twice with PBS (2 min each) and fixed with freshly prepared 4.0% (w/v) paraformaldehyde prewarmed at 37 °C. The cell samples were rinsed with PBS and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100. After incubation for 1 h at room temperature (21 °C) with 5% (v/v) normal donkey serum to block non-specific binding, the cell samples were incubated for 2 h at room temperature with mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG M2 antibody (5.0 μg/ml; Sigma) or rabbit anti-calnexin N-terminal polyclonal antibody (1.0 μg/ml; StressGen Biotechnologies, Victoria, BC, Canada). The cell samples were washed three times with PBS and were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with Cy2 (a cyanine dye and a fluorophore)-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG and/or Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, U.S.A.). The cells were then co-stained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (1:900) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, U.S.A.) and analysed with a confocal fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX61; Olympus, Nashua, NH, U.S.A.).

RESULTS

Identification of the human cardiolipin gene

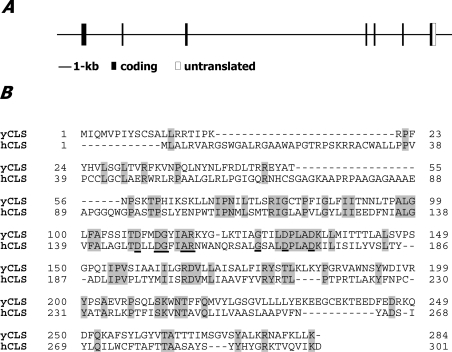

The hCLS1 gene was initially identified from BLAST analysis of human genomic databases using the yeast CRD protein sequence as a query. A 1.2 kb cDNA clone encoding a putative hCLS enzyme was identified from the NCBI genomic database (accession no. AF241784) and then cloned by PCR amplification using primers designed from the predicated coding region and a cDNA library from the human liver. The hCLS1 gene consists of seven exons (Figure 1A) and is mapped to chromosome 20p13-p12.3, adjacent to MCM8 (minichromosome maintenance protein-8) gene. The predicted hCLS1 protein sequence shares extensive homology with the yeast CLS1 (Figure 1B). The open frame of the hCLS1 gene predicts a 301-amino-acid protein of 32.6 kDa that carries features for a transmembrane protein as well as a sequence motif [D(X)2DG(X)2AR(X)8–9G(X)3D(X)3D] that is conserved among members of the CLS family from yeast to plants (Figure 1B, underlined) [27]. BLAST analyses with genomic and EST (expressed sequence tag) databases identified multiple hCLS1 orthologues from Caenorhabditis elegans to different species of mammals (results not shown).

Figure 1. Genomic structure of the hCLS1 gene and sequence comparison with yeast CLS1.

The hCLS1 gene consists of seven exons (A) that are mapped to chromosome 20p13-p12.3. The coding region is indicated by solid bars, whereas the 3′-untranslated region is marked by an open box. The predicted hCLS1 protein sequence shares extensive homology with the yeast CLS1 (shaded regions) (B), and carries a sequence motif [D(X)2DG(X) 2AR(X)8–9G(X)3D(X)3D] (underlined) conserved among members of the CLS family from yeast to plants.

Tissue distribution of the hCLS1 mRNA

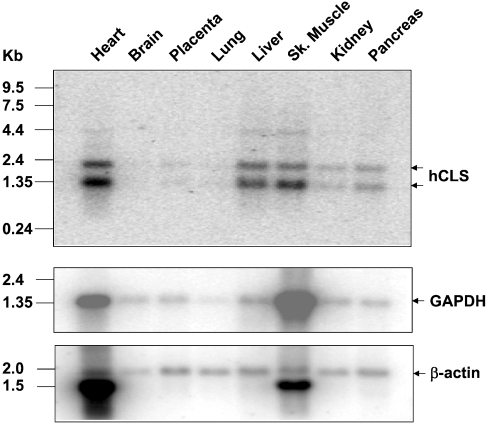

The tissue expression profile of hCLS1 mRNA was analysed by Northern-blot analysis using radiolabelled hCLS1 cDNA as a probe. The same blot was reprobed with β-actin and GAPDH as internal controls for mRNA loading. Two hCLS1 mRNA splice isoforms of 1.35 and 2.40 kb in length respectively were detected in various human tissues (Figure 2). In addition, a weak band of 4.4 kb was also detectable from some of the tissues, which probably represents a splice variant that carries intron sequences. The hCLS1 gene was most abundantly expressed in tissues that possess a high level of mitochondrial content. When normalized with the expression level of the splice variant of the β-actin gene (Figure 2, indicated by an arrow), the hCLS1 mRNA level was the highest in heart, followed by skeletal muscle, liver, pancreas and kidney. In contrast, hCLS1 expression was very low in other tissues including brain, placenta and lung.

Figure 2. Tissue distribution of the hCLS1 mRNAs as examined by Northern-blot analyses.

A human multiple tissue blot with 2 μg of poly(A)+ RNA from each tissue was hybridized with radiolabelled probe prepared from the full-length cDNA clone of the hCLS1 gene (top panel). The same blot was stripped of residual radioactivity and reprobed with radiolabelled GAPDH as well as β-actin cDNA probes as internal controls for mRNA loading respectively (middle and bottom panels). Sk., skeletal.

Analysis of CLS activity of the recombinant hCLS1 transiently expressed in COS-7 cells

To facilitate Western blot and immunocytohistochemical detection of the recombinant hCLS1, we engineered a mammalian expression vector by attaching a FLAG tag to the N-terminus of hCLS1. The FLAG–hCLS1 expressed in COS-7 cells migrated on SDS/PAGE with an apparent molecular mass of 32 kDa (Figure 3), which is consistent with the molecular mass predicted from the open reading frame of the hCLS1 gene, suggesting no major glycosylation of the enzyme in mammalian cells. The C-terminus of the recombinant hCLS1 protein contains a major site for degradation, as indicated by the presence of a 28 kDa protein band on SDS/PAGE (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Western-blot analysis of the recombinant hCLS1 protein.

The recombinant FLAG–hCLS1 protein transiently expressed in COS-7 cells was resolved on SDS/PAGE and analysed by Western-blot analysis using anti-FLAG antibodies. The recombinant hCLS1 exhibited two moieties, with molecular masses of 32 and 27 kDa respectively. The 32 kDa band represents the full-length hCLS1 protein, whereas the 27 kDa band represents a proteolytic degradation product from the C-terminus.

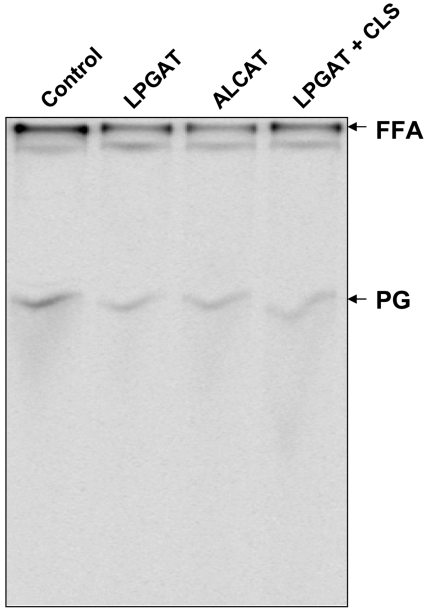

To provide direct evidence that the hCLS1 cDNA encodes a CLS, the recombinant hCLS1 protein transiently expressed in COS-7 cells was analysed for CLS activity using two different assay conditions. In the first assay condition, the FLAG–hCLS1 was co-expressed with the human LPGAT1, which was used to synthesize [14C]PG as a substrate for the CLS assay. LPGAT1 is an acyltransferase recently identified in this laboratory, which catalyses the synthesis of PG by acylating LPG to PG [15]. As a positive control for detection of radiolabelled cardiolipin, recombinant ACLAT1 was used to catalyse the synthesis of [14C]cardiolipin with monolysocardiolipin and [14C]oleoyl-CoA as substrates as previously reported from this laboratory [16]. As demonstrated in Figure 4(A), the recombinant hCLS1 catalysed efficiently the synthesis of radiolabelled cardiolipin only in the presence of both CDP-DAG and [14C]PG that was produced by LPGAT1. In contrast, overexpression of the empty vector or LPGAT1 alone in COS-7 cells did not result in a significant increase in radiolabelled cardiolipin. The specificity of the enzyme activity was further analysed by using an alternative assay condition. In this assay, the recombinant hCLS1 expressed in COS-7 cells was analysed for CLS enzyme activity with purified [14C]PG in the presence/absence of CDP-DAG as a substrate. As shown by Figure 4(B), the recombinant hCLS1 catalysed the synthesis of cardiolipin only in the presence of both CDG-DAG and [14C]PG.

Figure 4. Analysis of CLS activity of the recombinant hCLS1 enzyme.

The recombinant hCLS1 protein transiently expressed in COS-7 cells was analysed for CLS activity using two different assay conditions. In the first assay condition (A), FLAG–hCLS1 was co-expressed with the human LPGAT1, which was used to synthesize [14C]PG as a substrate for the CLS assay. CLS activity was assayed in a mixture of 200 μl containing 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.0), 4.0 mM MgCl2, 20 μM [14C]oleoyl-CoA, 2.0 mM LPG and 2.0 mM CDP-DAG. As a positive control for the detection of radiolabelled cardiolipin, recombinant ACLAT1 was used to catalyse the synthesis of [14C]cardiolipin with monolysocardiolipin and [14C]acyl-CoA as substrates. In the second assay condition (B), the recombinant hCLS1 expressed in COS-7 cells was analysed for CLS enzyme activity with purified [14C]PG in the presence/absence of CDP-DAG as a substrate. The recombinant hCLS1 catalysed the synthesis of cardiolipin only in the presence of both CDG-DAG and [14C]PG. The radiolabelled PG and cardiolipin (CL) are indicated by arrowheads. FFA, non-esterified fatty acid.

To eliminate the possibility that the increased cardiolipin synthesis observed from the enzyme assays might be caused by an elevated activity of the endogenous PGS as a result of the hCLS1 overexpression in COS-7 cells, we next analysed the endogenous PGS enzyme activity using CDP-DAG and [14C]glycerol-3-phosphate as substrates. As demonstrated in Figure 5, a similar level of [14C]PG production was detected from the COS-7 cells transfected with the hCLS1 expression plasmid to that from the control cells transfected with empty plasmid vector, suggesting that hCLS1 overexpression did not have any significant effect on the activity of the endogenous PGS enzyme in the COS-7 cells.

Figure 5. Effects of hCLS1 overexpression on the endogenous PGS1 activity in COS-7 cells.

COS-7 cells were either transiently transfected with the empty vector (control), the LPGAT1 expression vector or the ALCAT1 expression vector or co-transfected with the LPGAT1 expression vector and the hCLS1 expression vector respectively. Cells were lysed 48 h after the transfection and then analysed for PGS activity in a 200 μl reaction mixture containing 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.4), 0.25 mM CDP-DAG, 0.1 mM [14C]glycerol-3-phosphate and 50 μg of cell lysate protein from COS-7 cells transiently transfected with the various vectors indicated above. The resulting lipid products were extracted and subjected to TLC analysis as described in the Materials and methods section. The PGS activity was measured by the production of [14C]PG as indicated by an arrow.

The recombinant hCLS1 enzyme catalysed efficiently the synthesis of cardiolipin in intact COS-7 cells

In order to provide further evidence that the hCLS1 gene encodes a CLS, we next analysed cardiolipin synthesis in intact COS-7 cells transiently transfected with a fixed amount of LPGAT1 plasmid (2 μg) and an increasing amount of the hCLS1 expression plasmid, ranging from 0 to 4.5 μg. The transfected COS-7 cells were cultured in the presence of [14C]oleoyl-CoA for 24 h to label the newly synthesized lipids. The total lipids were extracted from the cultured cells and analysed by TLC. As demonstrated in Figure 6, the recombinant hCLS1 catalysed efficiently the synthesis of cardiolipin in intact COS-7 cells, as indicated by the increased levels of radiolabelled cardiolipin in proportion to the amount of hCLS1 expression plasmid used in the transient transfection experiment.

Figure 6. Analysis of CLS activity of the recombinant hCLS1 in intact COS-7 cells.

COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with 2 μg of LPGAT1 expression plasmid and the indicated amount of hCLS1 expression plasmid (0.0–4.5 μg), and incubated in the presence of 0.16 mM [14C]oleoyl-CoA for 24 h at 37 °C. Total lipids were then extracted from the cultured COS-7 cells and subjected to TLC analysis as described in the Materials and methods section. FFA, non-esterified fatty acid; CL, cardiolipin.

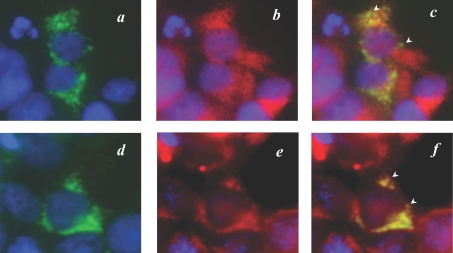

The recombinant hCLS1 was exclusively localized in mitochondria when expressed in COS-7 cells

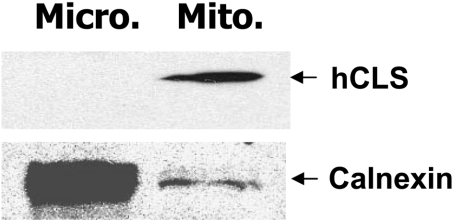

We next performed immunocytohistochemical analyses of the recombinant FLAG–hCLS1 transiently expressed in COS-7 cells to define its subcellular localization in intact cells. Cells were processed, 48 h after transfection, for mitochondrial staining with MitoTracker Red CMXRos or indirect immunofluorescence staining with antibodies specific for the FLAG epitope (green) as well as calnexin (red). MitoTracker Red is a cell-permeant fluorescent probe that accumulates in active mitochondria, whereas calnexin is an ER-resident protein commonly used as a marker for ER. Cells were also counterstained with DAPI to visualize nuclei (blue). The FLAG–hCLS1 protein expressed in COS-7 cells displayed a perinuclear and punctated pattern (Figures 7a and 7d). The FLAG–hCLS1 protein was not colocalized with calnexin (Figure 7b), as demonstrated by the well-separated green (FLAG–hCLS1) and red (calnexin) colours in the merged image (Figure 7c). In contrast, the FLAG-tagged hCLS1 protein was clearly co-localized with the MitoTracker Red (Figure 7e), as demonstrated by the yellow colour in the merged image (Figure 7f). As a negative control of the immunostaining process, no significant staining was observed in mock-transfected cells stained with anti-FLAG antibody or with normal mouse IgG (results not shown). The results were further corroborated by subcellular fractionation analysis, which demonstrated conclusively that the recombinant hCLS1 protein was only localized in the mitochondrial fraction (Figure 8).

Figure 7. Subcellular localization analysis of the recombinant FLAG–hCLS1 transiently expressed in COS-7 cells.

COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with the FLAG–hCLS1 expression plasmid. The cells were processed, 48 h after transfection, for subcellular localization analysis by indirect immunofluorescence staining with antibodies specific for the FLAG epitope (a, d) and calnexin (b) or mitochondrial staining with MitoTracker Red CMXRos (e) respectively. The cells were then counterstained with DAPI to visualize nuclei (blue). As shown by (c), a merged picture of (a, b), hCLS1 was not co-localized with calnexin, as indicated by well-separated green and red colours (indicated by arrowheads). In contrast, the recombinant hCLS1 demonstrated a clear co-localization with the staining pattern of mitochondria, as shown by the yellow colour (highlighted by arrowheads) in (f), which is a merged picture of (d, e). The results demonstrate that FLAG–hCLS1 is localized to the mitochondria.

Figure 8. Subcellular fractionation analysis of the recombinant hCLS1 expressed in COS-7 cells.

COS-7 cells transiently transfected with FLAG–hCLS1 expression vector or empty vector were homogenized and fractionated into mitochondrial (Mito.) and microsomal (Micro.) fractions by differential sedimentation. The fractions were analysed by Western-blot analysis using antibodies to FLAG and calnexin, which were used as markers for hCLS1 and ER respectively. The results demonstrated that hCLS1 was exclusively localized in the mitochondrial fraction.

DISCUSSION

In eukaryotic cells, CLS is involved in the final step of cardiolipin synthesis by catalysing the transfer of a phosphatidyl residue from CDP-DAG to PG. In yeast S. cerevisiae, CLS plays an important role in maintaining mitochondrial function. Mutation of the yeast CRD1 gene encoding CLS results in cardiolipin deficiency accompanied by impaired viability, decreased membrane potential and defective oxidative phosphorylation [10]. Cardiolipin synthesis also plays an important role in regulating mitochondrial function in mammals. Cardiolipin deficiency in CHO cells caused by mutation of the PGS1 gene results in morphological and functional mitochondrial abnormalities, manifested by more stringent temperature-sensitivity for cell growth in glucose-deficient medium and by decreased ATP production [11]. The mutant CHO cells demonstrate an increased glycolysis, decreased oxygen consumption and defective respiratory electron transport chain activity. Furthermore, cardiolipin deficiency has recently been implicated in mitochondrial dysfunction associated with metabolic diseases [18,28]. However, a lack of a gene encoding the mammalian CLS has hindered progress in elucidating the role of CLS in regulating mitochondrial function and the related metabolic implications in mammals. In the present study, we report the identification and characterization of a human gene encoding the first mammalian CLS, hCLS1. The hCLS1 was identified based on its sequence homology to yeast and plant CLSs. The recombinant hCLS1 expressed in COS-7 cells catalysed efficiently the synthesis of cardiolipin by using PG and CDP-DAG as substrates. Furthermore, overexpression of hCLS1 resulted in significantly increased levels of cardiolipin synthesis in intact COS-7 cells transiently transfected with the hCLS1 expression plasmid. Consistent with the projected roles of CLS in maintaining mitochondrial function, the recombinant hCLS1 expressed in COS-7 cell was exclusively localized in the mitochondria by both immunohistochemical and subcellular fractionation analyses. Finally, during the revision of this manuscript, two papers reported the cloning and characterization of the same gene [29,30], which are consistent with our results on hCLS1.

In support of a role of cardiolipin in mitochondrial function, the hCLS1 gene was predominantly expressed in tissues actively involved in energy metabolism. Cardiolipin is one of the principal phospholipids of the mammalian heart, a tissue that has perpetually high energy demands and requires excessive fatty acid oxidation in the mitochondria to provide ATP. Consequently, cardiolipin deficiency in ischaemia and reperfusion results in mitochondrial dysfunction manifested by a decrease in oxidative capacity, loss of cytochrome c and generation of reactive oxygen species [17–19]. Consistent with an important role of cardiolipin in heart function, the hCLS1 gene exhibited the highest expression level in the heart of humans. In addition, high levels of hCLS1 expression were also detected in key insulin-sensitive tissues involved in regulating glucose homoeostasis, including skeletal muscle, liver and pancreas. The tissue expression profile of the hCLS1 gene is of particular interest in light of the recently proposed role of mitochondrial dysfunction in insulin resistance associated with obesity [31]. Thus the cloning and characterization of the hCLS1 gene has laid the foundation for future studies to investigate a role of cardiolipin synthesis in heart function as well as energy homoeostasis.

References

- 1.Schlame M., Hostetler K. Y. Cardiolipin synthase from mammalian mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1997;1348:207–213. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(97)00119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mileykovskaya E., Zhang M., Dowhan W. Cardiolipin in energy transducing membranes. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2005;70:154–158. doi: 10.1007/s10541-005-0095-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schlame M., Rua D., Greenberg M. L. The biosynthesis and functional role of cardiolipin. Prog. Lipid Res. 2000;39:257–288. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(00)00005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orrenius S., Zhivotovsky B., Nicotera P. Regulation of cell death: the calcium-apoptosis link. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;4:552–565. doi: 10.1038/nrm1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lutter M., Fang M., Luo X., Nishijima M., Xie X., Wang X. Cardiolipin provides specificity for targeting of tBid to mitochondria. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:754–761. doi: 10.1038/35036395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McMillin J. B., Dowhan W. Cardiolipin and apoptosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1585:97–107. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00329-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang F., Gu Z., Granger J. M., Greenberg M. L. Cardiolipin synthase expression is essential for growth at elevated temperature and is regulated by factors affecting mitochondrial development. Mol. Microbiol. 1999;31:373–379. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang M., Su X., Mileykovskaya E., Amoscato A. A., Dowhan W. Cardiolipin is not required to maintain mitochondrial DNA stability or cell viability for Saccharomyces cerevisiae grown at elevated temperatures. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:35204–35210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306729200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gohil V. M., Hayes P., Matsuyama S., Schagger H., Schlame M., Greenberg M. L. Cardiolipin biosynthesis and mitochondrial respiratory chain function are interdependent. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:42612–42618. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402545200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhong Q., Gohil V. M., Ma L., Greenberg M. L. Absence of cardiolipin results in temperature sensitivity, respiratory defects, and mitochondrial DNA instability independent of pet56. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:32294–32300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403275200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohtsuka T., Nishijima M., Suzuki K., Akamatsu Y. Mitochondrial dysfunction of a cultured Chinese hamster ovary cell mutant deficient in cardiolipin. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:22914–22919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hatch G. M. Cardiolipin: biosynthesis, remodeling and trafficking in the heart and mammalian cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 1998;1:33–41. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.1.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawasaki K., Kuge O., Chang S. C., Heacock P. N., Rho M., Suzuki K., Nishijima M., Dowhan W. Isolation of a Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cDNA encoding phosphatidylglycerophosphate (PGP) synthase, expression of which corrects the mitochondrial abnormalities of a PGP synthase-defective mutant of CHO-K1 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:1828–1834. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.3.1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang S. C., Heacock P. N., Mileykovskaya E., Voelker D. R., Dowhan W. Isolation and characterization of the gene (CLS1) encoding cardiolipin synthase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:14933–14941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.14933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang Y., Cao J., Shi Y. Identification and characterization of a gene encoding human LPGAT1, an endoplasmic reticulum-associated lysophosphatidylglycerol acyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:55866–55874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406710200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cao J., Liu Y., Lockwood J., Burn P., Shi Y. A novel cardiolipin-remodeling pathway revealed by a gene encoding an endoplasmic reticulum-associated acyl-CoA:lysocardiolipin acyltransferase (ALCAT1) in mouse. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:31727–31734. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402930200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paradies G., Petrosillo G., Pistolese M., Ruggiero F. M. Reactive oxygen species generated by the mitochondrial respiratory chain affect the complex III activity via cardiolipin peroxidation in beef-heart submitochondrial particles. Mitochondrion. 2001;1:151–159. doi: 10.1016/s1567-7249(01)00011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petrosillo G., Ruggiero F. M., Di Venosa N., Paradies G. Decreased complex III activity in mitochondria isolated from rat heart subjected to ischemia and reperfusion: role of reactive oxygen species and cardiolipin. FASEB J. 2003;17:714–716. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0729fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paradies G., Petrosillo G., Pistolese M., Ruggiero F. M. The effect of reactive oxygen species generated from the mitochondrial electron transport chain on the cytochrome c oxidase activity and on the cardiolipin content in bovine heart submitochondrial particles. FEBS Lett. 2000;466:323–326. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01082-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ostrander D. B., Sparagna G. C., Amoscato A. A., McMillin J. B., Dowhan W. Decreased cardiolipin synthesis corresponds with cytochrome c release in palmitate-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:38061–38067. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107067200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cao S. G., Cheng P., Angel A., Hatch G. M. Thyroxine stimulates phosphatidylglycerolphosphate synthase activity in rat heart mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1995;1256:241–244. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(95)00035-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El Bawab S., Birbes H., Roddy P., Szulc Z. M., Bielawska A., Hannun Y. A. Biochemical characterization of the reverse activity of rat brain ceramidase: a CoA-independent and fumonisin B1-insensitive ceramide synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:16758–16766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009331200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Summers S. A., Nelson D. H. A role for sphingolipids in producing the common features of type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome X, and Cushing's syndrome. Diabetes. 2005;54:591–602. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.3.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gorski J., Zendzian-Piotrowska M., de Jong Y. F., Niklinska W., Glatz J. F. Effect of endurance training on the phospholipid content of skeletal muscles in the rat. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1999;79:421–425. doi: 10.1007/s004210050532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ames B. N., Shigenaga M. K., Hagen T. M. Mitochondrial decay in aging. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1995;1271:165–170. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(95)00024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schlame M., Hostetler K. Y. Solubilization, purification, and characterization of cardiolipin synthase from rat liver mitochondria: demonstration of its phospholipid requirement. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:22398–22403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katayama K., Sakurai I., Wada H. Identification of an Arabidopsis thaliana gene for cardiolipin synthase located in mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 2004;577:193–198. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lesnefsky E. J., Chen Q., Slabe T. J., Stoll M. S., Minkler P. E., Hassan M. O., Tandler B., Hoppel C. L. Ischemia, rather than reperfusion, inhibits respiration through cytochrome oxidase in the isolated, perfused rabbit heart: role of cardiolipin. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2004;287:H258–H267. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00348.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu B., Xu F. Y., Jiang Y. J., Choy P. C., Hatch G. M., Grunfeld C., Feingold K. R. Cloning and characterization of a cDNA encoding human cardiolipin synthase (hCLS1) J. Lipid Res. 2006;47:1140–1145. doi: 10.1194/jlr.C600004-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Houtkooper R. H., Akbari H., van Lenthe H., Kulik W., Wanders R. J., Frentzen M., Vaz F. M. Identification and characterization of human cardiolipin synthase. FEBS. Lett. 2006;580:3059–3064. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lowell B. B., Shulman G. I. Mitochondrial dysfunction and type 2 diabetes. Science. 2005;307:384–387. doi: 10.1126/science.1104343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]