Abstract

Lipopeptide MSI-843 consisting of the nonstandard amino acid ornithine (Oct–OOLLOOLOOL–NH2) was designed with an objective towards generating non-lytic short antimicrobial peptides, which can have significant pharmaceutical applications. Octanoic acid was coupled to the N-terminus of the peptide to increase the overall hydrophobicity of the peptide. MSI-843 shows activity against bacteria and fungi at micromolar concentrations. It permeabilizes the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacterium and a model membrane mimicking bacterial inner membrane. Circular dichroism investigations demonstrate that the peptide adopts α-helical conformation upon binding to lipid membranes. Isothermal titration calorimetry studies suggest that the peptide binding to membranes results in exothermic heat of reaction, which arises from helix formation and membrane insertion of the peptide. 2H NMR of deuterated-POPC multilamellar vesicles shows the peptide-induced disorder in the hydrophobic core of bilayers. 31P NMR data indicate changes in the lipid head group orientation of POPC, POPG and Escherichia coli total lipid bilayers upon peptide binding. Results from 31P NMR and dye leakage experiments suggest that the peptide selectively interacts with anionic bilayers at low concentrations (up to 5 mol%). Differential scanning calorimetry experiments on DiPOPE bilayers and 31P NMR data from E. coli total lipid multilamellar vesicles indicate that MSI-843 increases the fluid lamellar to inverted hexagonal phase transition temperature of bilayers by inducing positive curvature strain. Combination of all these data suggests the formation of a lipid–peptide complex resulting in a transient pore as a plausible mechanism for the membrane permeabilization and antimicrobial activity of the lipopeptide MSI-843.

Keywords: Lipopeptide, Antimicrobial activity, Membrane permeabilization, Solid-state NMR, Oriented bilayers, Curvature strain

1. Introduction

Antimicrobial peptides are produced as a part of the host defense mechanisms by various organisms that include microbes, insects, plants, vertebrates and mammals [1]. Many of the antimicrobial peptides exert their activity by interacting non-specifically with target biological membranes [2-5]. These peptides are characterized as having hydrophobic, cationic and amphiphathic features even though the exact attributes are not clearly known. Upon binding to the membrane, they assume a parallel or perpendicular or an oblique angular orientation with respect to the membrane normal axis [6-8]. These peptides adopt an amphiphathic structure in the membrane embedded state in such a way that the hydrophobic side chains are inserted deep into the membrane while the charged and polar residues on the hydrophilic portion interact with the head groups of phospholipids in the membrane.

Lipopeptides are unique among the antimicrobial peptides in that they are relatively smaller in size as compared to other cationic antimicrobial peptides, and yet, exhibit excellent antimicrobial activity. Fatty acid acylation of antimicrobial peptides of bacterial and fungal origin have mostly been limited to non-gene-encoded peptides such as echinocandin [9], polymyxins [10], daptomycin [11] lipopeptaibols [12,13] and syrinomycin, syringotoxin and syringopeptin from Pseudomonas syringae [14]. Enzymatic fatty acid acylation is one of the post-translational modifications of peptides involved in functional [15,16] and structural roles [17]. It has been postulated that fatty acylation of proteins are necessary to increase their membrane association and sorting into specific sub-cellular localizations [16,18]. Consequently, several studies to assess the effect of acylation have revealed that conjugation of fatty acid to cationic peptides enhances their antimicrobial activity [19-23]. However, it is not clear if fatty acylation influences the association of hydrophilic portions of peptides with membranes or modulates the orientation of peptides in membranes. Therefore, it would be relevant to study the interactions of antimicrobial lipopeptides in neutral and anionic model membranes as it would help in understanding the biophysical properties governing the association of fatty acylated peptides with biological membranes.

Lactoferricin H, the proteolytic product of human lactoferrin, consists of an amphiphathic α-helical region (residues 21–31) of lactoferrin and has been reported to show enhanced antibacterial activity compared to the intact lactoferrin [24]. Lipophilic modification at the C-terminus of a peptide based on residues 21–31 of human lactoferrin has resulted in enhanced antimicrobial activity against Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria [25]. The alkyl chain (6-octanoyl/heptanoyl diaminobutyl group) in the cationic cyclic antimicrobial peptide polymixin B has been shown to be essential for its antimicrobial activity [26]. Removal of 6-octanoyl/heptanoyl diaminobutyl moeity from polymyxin B resulted in the loss of activity [27]. Aliphatic acids can, therefore, be used to increase the hydrophobicity and membrane association of short cationic peptides and consequently improve the antimicrobial activity.

For the present study, a synthetic lipopeptide MSI-843 (Oct–OOLLOOLOOL–NH2), with a short helical stretch and an octyl chain at the N-terminus, was designed and interactions with lipid bilayers and biological activities were determined to understand the molecular mechanism of membrane permeabilization. CD and ITC experiments were used to determine the energy involved in the secondary structure formation and membrane insertion. 31P NMR experiments were used to determine the peptide-induced changes in the head group conformation of lipids. 2H NMR experiments provided a measure of the peptide-induced disorder in the hydrophobic core of bilayers. DSC and 31P NMR provided information on peptide-induced curvature strain in the membrane. Our results also show that the lipopeptide did not cause hemolysis at concentrations required for antimicrobial activity. Our data from this study suggest that the peptide–lipid complex induces local defects in the membrane that form the basis for the observed antimicrobial activity of the lipopeptide.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

POPG, POPC, POPC-d31, POPE, DiPoPE and Escherichia coli total lipid extract were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Chloroform and methanol were procured from Aldrich Chemical Inc. (Milwaukee, WI), and naphthalene was from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). All the chemicals were used without further purification. The peptide was synthesized by Genaera Corporation (Plymouth Meeting, PA).

2.2. Outer membrane permeabilization assay

The outer membrane permeabilizing ability was investigated using the 8-anilinonapthalene-1-sulfonic acid (ANS) uptake assay [28], using E. coli strain L21 (DE3). Bacterial cells from an overnight culture were inoculated into LB medium. Cells from the mid-log phase were centrifuged and washed with buffer (10 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4), and then resuspended in the same buffer to an OD600 of 0.065. To 3.0 mL of the cell suspension in a cuvette, a stock solution of ANS was added to a final concentration of 5.0 μM. The degree of membrane permeabilization as a function of peptide concentration was observed by the increase in fluorescence intensity at ∼ 500 nm.

2.3. High-sensitivity titration calorimetry

The heat of peptide-into-lipid mixing reaction was measured using a high sensitivity titration calorimeter as described elsewhere [29] (Calorimetry Sciences Corporation, Model CSC-4200, Utah, USA). Peptide and lipid solutions were degassed under vacuum prior to use. The calorimeter was calibrated as recommended by the manufacturer. The heats of dilution for successive 10 μL injections of the peptide solution into buffer were insignificant compared to the heats of peptide–lipid reaction. The heat of peptide–lipid binding was determined by integrating the area under each titration curve using the built-in Bindworks software.

2.4. Circular dichroism

Small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs) were prepared as follows. A 10 mM Tris buffer (150 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) was added to dry lipid film and subjected to vortex and sonication to obtain a clear dispersion of SUVs. A40 μM peptide stock solution was prepared in Tris buffer. CD spectra were recorded (AVIV CD spectropolarimeter, Lakewood, NJ) at 25 °C using samples with peptide / lipid ratios 1 : 100 and 1 : 200 over the range from 200 to 250 nm. A 5 mm quartz cuvette was used for measurements. Contributions from the buffer and SUVs were removed by subtracting the spectra of corresponding control samples without peptide. The mean helix content, fH, was estimated from the ellipticity value at λ222 nm, [Θ]222, according to the empirical equation of Rohl and Baldwin [30]:

| 1 |

where ΘC and ΘH are given by the following expressions:

| 2 |

| 3 |

where T is the temperature in degree Celsius and Nr is the number of residues in the peptide.

2.5. Dye leakage assay

Carboxyfluorescein dye entrapped small unilamellar vesicles were prepared as described elsewhere [31]. The dye-containing vesicles were then purified by gel filtration chromatography, using a Sephadex G-75 column. Fluorescence emission intensity as a function of time was recorded using the excitation wavelength 490 nm and emission wavelength 520 nm. The maximum leakage from each sample was determined by adding triton X-100.

2.6. Hemolysis assay

Peptide-induced hemolysis was observed as previously reported [31]. Serum free human red blood cells were suspended in 10 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.4, NaCl 150 mM, EDTA 2 mM) and incubated with serial concentrations of peptide at 37 °C for 30 min. After centrifugation, the absorbance of the supernatant was measured at A540 nm. The 100% hemolysis (A540 ∼ 0.608) was achieved using neat water. In a control experiment, cells were incubated in buffer without peptide, and the A540 nm value was used as the blank.

2.7. Differential scanning calorimetry

DSC experiments were performed using the Nano-DSC II machine (Calorimetry Sciences, Provo, UT). A 10 mM Tris buffer (150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, pH = 7.4) and DiPoPE multilamellar vesicles were degassed under vacuum for 15 min prior to loading into the machine. Samples were loaded below the main phase transition temperature for the lipid mixture and put under 3.00 atm of pressure. Eight scans were run for each sample, with 10 min equilibration time between each scan. Heating and cooling rates of 1.0 °C/min were used over a temperature range of 10–60 °C. The raw data were then converted to molar heat capacity using the CPCalc program provided with the calorimeter. For each conversion, the average lipid molecular weight for each sample and a partial specific volume of 0.956 mL/g were used. Experiments were performed on DiPoPE MLVs with peptide / lipid mole ratios 1 : 500 and 1 : 250.

2.8. Preparation of samples for NMR measurements

All mechanically aligned lipid bilayer samples used for NMR experiments were prepared using the recently published naphthalene procedure [32]. Briefly, 4 mg of lipids and an appropriate amount of peptide were dissolved in CHCl3/CH3OH (2 : 1) mixture containing equimolar amounts of naphthalene. The solution was spread on thin glass plates (11 mm × 22 mm × 50 μm, Paul Marienfeld GmbH and Co., Bad Mergentheim, Germany) and then taken to dryness. The lipid films were dried under vacuum for at least 10 h to remove naphthalene and any residual organic solvents. The glass plates containing lipid films were placed in a hydration chamber that was maintained at ∼ 93% relative humidity [33] for 2–3 days at 37 °C. About 2–5 μL of water was sprayed onto the surface of the lipid–peptide film on glass plates. The glass plates were stacked, wrapped with parafilm, sealed in plastic bags (Plastic Bagmart, Marietta, GA), and then incubated at 4 °C for 6–24 h.

MLVs for NMR experiments were prepared as follows. About 5.0 mg of lipid and the desired amount of peptide were dissolved in CHCl3/CH3OH (2 : 1) mixture. The solvent was removed under N2 and lipid–peptide mixture was dried under vacuum overnight. Deuterium-depleted water (Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI) was added and the mixture was subjected to several freeze–thaw cycles with a gentle vortex to produce MLVs.

2.9. Solid-state NMR

All experiments were performed on a Chemagnetics/Varian Infinity 400 MHz solid-state NMR spectrometer operating with resonance frequencies of 400.138, 161.979, and 61.424 MHz for 1H, 31P, and 2H nuclei, respectively. Unless otherwise stated, all experiments were performed at 30 °C. A Chemagnetics temperature controller unit was used to maintain the sample temperature, and the sample was equilibrated for at least 30 min before starting each experiment. All experiments on oriented samples were performed with the bilayer normal parallel to the external magnetic field, which is defined as the parallel orientation. The 31P spectra of mechanically aligned samples were obtained using a home-built double resonance probe, which has a four turn square coil (12 ×12 × 4 mm) constructed using a 2 mm wide flat-wire with a spacing of 1 mm between turns. 31P and 2H spectra of MLVs were obtained using a Chemagnetics double resonance probe. A typical 31P 90°-pulse length of 3.1 μs was used in both probes. 31P chemical shift spectra were obtained using a spin-echo sequence (90°-τ -180°-τ -acquire), 30 kHz proton-decoupling radio frequency field, 50 kHz spectral width, and a recycle delay of 3 s. A typical spectrum required the co-addition of 100–1000 transients. The 31P chemical shift spectra were referenced relative to 85% H3PO4 on thin glass plates (0 ppm). 2H quadrupole coupling spectra were obtained using a quadrupole-echo sequence (90°-τ -90°-τ -acquire) with a 90°-pulse length of 3.0 μs, a spectral width of 100 kHz, and a recycle delay of 2 s. A typical spectrum required the co-addition of 15,000–20,000 transients. Data processing was accomplished using the software Spinsight (Chemagnetics/Varian) on a Sun Sparc workstation. Spectral simulation for the 31P spectra was done on a PowerBook G4 using a FORTRAN program. The 2H spectra of POPC-d31 multilamellar dispersions were processed and de-Paked using MATLAB software [34,35].

3. Results

3.1. Peptide design

MSI-843 has only 10 amino acids with a helical propensity and can fold into a maximum of two helical turns. The octyl chain at the N-terminus of the peptide can increase the overall hydrophobicity of the peptide and improve the binding affinity for lipid membranes. The peptide has 6 positively charged ornithine residues, and therefore, it can tightly bind to the negatively charged bacterial membranes and elicit antimicrobial activity. It is unlikely that the short amphipathic α-helical MSI-843 would form a transmembrane pore structure, as a minimum of 21-residues in the α-helical conformation is required to span the membrane bilayer [36]. Therefore, MSI-843 can be expected to behave as a non-lytic antimicrobial lipopeptide. It is worth mentioning here that non-lytic short antimicrobial peptides are better candidates for pharmaceutical applications [3].

3.2. Antimicrobial activity and membrane permeabilization

The minimal inhibitory concentrations of MSI-843 for E. coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Candida albicans given in Table 1 are the average of three independent experiments. As seen in Table 1, MSI-843 showed variable activity against various microorganisms at micromolar concentrations. The peptide exhibited a greater activity on P. aeruginosa and reduced activity on C. albicans. At these concentrations, MSI-843 did not show any observable hemolytic activity. However, ∼ 6% hemolysis was observed at 100 μg/mL of the peptide (data not shown). Therefore, an understanding of the biophysical features of MSI-843 was necessary as it would be useful for the future design of therapeutic peptides.

Table 1.

Antimicrobial activity of MSI-843 against different microbes

| Microorganism | Minimal inhibitory concentration (μM) |

|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | 12.5 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 12.5 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 1.6 |

| Candida albicans | 25.0 |

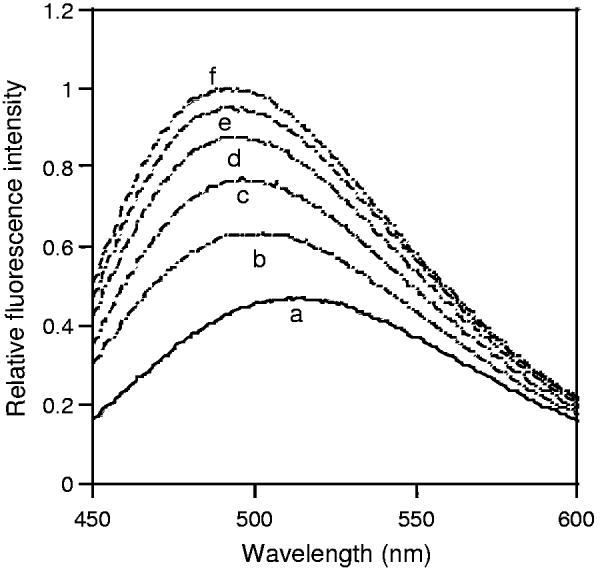

To assess the ability of MSI-843 to permeabilize the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria and determine other elements involved in the killing of bacteria, we measured the effective concentrations required to induce membrane permeabilization, and to kill the bacteria (MIC). Since ANS is a hydrophobic fluorophore, permeabilization of bacterial outer membrane can be assessed by measuring the enhancement in the fluorescence intensity of ANS, when ANS relocates into the membrane interior. The ANS uptake was assayed by incubating E. coli cells from mid-log phase culture with a constant amount of ANS (5.0 μM) and treating with serial concentrations of MSI-843. As shown in Fig. 1, the lipopeptide induced ANS uptake into E. coli cells in a concentration dependent manner. Observation of ANS fluorescence as a function of time showed that ANS uptake was complete within 10 min for any given peptide concentration (data not shown). A comparison of the MIC of MSI-843 for E. coli (cell density, OD600 = 0.02) with the concentrations required for ANS uptake (cell density, OD600 = 0.065) revealed that much less peptide was required to induce outer membrane permeabilization.

Fig. 1.

MSI-843 induced ANS uptake into E. coli membrane. Fluorescence spectra of ANS equilibrated with E. coli cells (a), and in the presence of 0.67 (b), 1.33 (c), 2.0 (d), 2.67 (e) and 3.35 μM (f) concentrations of MSI-843. The E. coli cell density, as measured at OD600, was 0.065.

Since the concentration required for outer membrane permeabilization was much less than the observed MIC, we determined the ability of MSI-843 to perturb a model membrane mimicking bacterial inner membrane. Carboxyfluorescein dye entrapped negatively charged SUVs were prepared using POPC/POPG (3 : 1) lipids [37]. The leakage of dye as a function of time for various concentrations of MSI-843 was observed. As shown in Fig. 2, significant leakage was observed at peptide concentrations > 0.73 μM (i.e., at P / L ratio > 0.028) which was less than the MIC of MSI-843 against E. coli.

Fig. 2.

Extent of carboxyfluoresceine dye leakage as a function of time and peptide concentration from POPC/POPG (3 : 1) SUVs. Lipid concentration was 26 μM.

3.3. Secondary structure

CD is a convenient technique to study the secondary structure of polypeptides in various media. To understand the nature of interaction between MSI-843 and lipid membranes, we examined the structure of MSI-843 in Tris buffer (pH = 7.4) and in the presence of POPC small unilamellar vesicles. The CD spectrum of MSI-843 in aqueous buffer (Fig. 3A, trace a) resembled the one for an unordered structure [38]. However, in the presence of POPC vesicles, the peptide showed two negative minima at ∼ 222 and 207 nm (Fig. 3A, trace b) indicating backbone conformational transitions upon binding to the membrane.

Fig. 3.

(A) CD spectra of MSI-843 in (a) Tris buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, pH = 7.4) and (b) 2 mM POPC in Tris buffer. Peptide concentration was 20 μM and P / L was 1 : 100. (B) Helical wheel projection of MSI-843.

3.4. Binding enthalpy

Using ITC, the enthalpy of binding reaction of MSI-843 was determined for POPC and POPC/POPG (3 : 1) SUVs at 25 °C by injecting the peptide solution into lipid vesicles. Results from one of the experiments are shown in Fig. 4A. The SUVs (20 mM) were taken in the calorimeter cell and titrated against 10 μL aliquots of the peptide solution (660 μM) in buffer. ITC showed an exothermic heat of reaction that remained steady at a value of ∼ 104 μJ per injection in the case of POPC SUVs. In a control experiment, the peptide solution was injected into buffer without SUVs. The heat of dilution observed was minimum (∼ 2.0 μJ) and this value was subtracted from the heat of reaction with different SUVs. The corrected heats of reaction, as determined from the area under the calorimetric traces, are given in Fig. 4B. The enthalpies for POPC and POPC/POPG (3 : 1) SUVs were −3.76 and −3.28 kcal/mol, respectively. The lipid concentration was maintained in large excess throughout the experiment.

Fig. 4.

Titration calorimetry thermograms of POPC and POPC/POPG (3 : 1) SUVs (20 mM) titrated against a solution of MSI-843 (660 μM) at 25 °C. Aliquots of a 10 μL peptide solution were added to the vesicle suspension in the reaction cell (V = 1.280 mL). Panel A shows the calorimeter trace for POPC SUVs. The enthalpy of reaction, which was calculated by integrating the calorimeter traces, is given in panel B (POPC SUVs filled circles; POPC/POPG (3 : 1) SUVs filled squares).

3.5. Peptide-induced changes in the lipid head group conformation and acyl chain disorder

2H NMR of selectively labeled POPC (POPC-d31) provides information on the dynamics of the hydrophobic part of the lipid bilayer while 31P NMR can be used to study the lipid head group conformation. To understand how the transient lesions cause leakage, we examined the 2H and31P NMR spectra of POPC, POPG and E. coli total lipid bilayers containing various amounts of MSI-843. Fig. 5A shows the de-Paked 2H NMR spectra of POPC-d31 MLVs containing MSI-843 in the P / L ratio of 0 : 100, 1 : 33 and 1 : 20. Pure bilayers exhibited resolved quadrupolar couplings ranging from + 25 to − 25 KHz (Fig. 5A). These splittings were characteristic of various dynamic orders of the methylene (CD2) units along the lipid acyl chain. The order parameters derived from the observed quadrupolar splittings [34,35] were maximum for the CD2 groups closer to the head group region and showed a decreasing trend along the acyl chain towards a minimum for the other end of the chain (Fig. 5B). When bilayers were incorporated with MSI-843 at P / L = 1:33 and 1:20 (3 and 5 mol%, respectively), significant reduction in the order parameters for the CD2 groups closer to the head group region was observed (Fig. 5B). This observation at higher peptide concentrations could be due to the aggregation of the membrane-bound peptide-monomers to form a pore complex and leading to a higher degree of disruption in the bilayers.

Fig. 5.

(A) de-Paked 2H quadrupole coupling spectra of POPC-d31 MLVs with and without the lipopeptide MSI-843. (B) 2H order parameter profiles for POPC-d31 bilayers containing 0 mol% (filled circles), 3 mol% (empty squares) and 5 mol% (empty circles) MSI-843.

To determine the peptide-induced structural changes in the lipid head group region, 31P NMR spectra obtained from MLVs (data not shown) were used to interpret the spectra obtained from aligned bilayers (Fig. 6). Spectra obtained from MLVs containing various concentrations of the peptide (up to 10 mol% peptide) showed lamellar phase powder pattern (data not shown) ruling out the presence of micelles and non-lamellar structure of lipids such as cubic and hexagonal phases. Since the peptide binding did not significantly change the 31P chemical shift span, peptide-induced changes in the dynamics of the lipid head group can be assumed to be negligible. Therefore, the spectra obtained from mechanically aligned bilayers can be interpreted using the chemical shift parameters measured from MLVs. Fig. 6 shows 31P NMR spectra of oriented POPC, POPG and E. coli total lipid bilayers with P / L ratio ranging from 0 to 1 : 20. Without the peptide, more than 90% of the spectral intensity was centered in the 0° frequency peak at ∼31 ppm (Fig. 6A, top trace), indicating that almost all POPC lipids were aligned with the bilayer normal parallel to the external magnetic field. When MSI-843 was incorporated up to P / L = 1 : 20, the 0° frequency peak shifted slightly towards higher frequency, indicating the interactions between MSI-843 and the phosphate head groups. However, no peaks representing non-lamellar structures were observed. These data suggest that MSI-843 interaction with POPC bilayers leads to a slight change in the lipid head group conformation.

Fig. 6.

31P spectra of oriented bilayers containing MSI-843. The lipid bilayer normal was parallel to Bo. Spectra of (A) POPC, (B) POPG, and (C) E. coli lipid bilayers were obtained at 25 °C with the indicated MSI-843 concentrations (mol%).

To probe the peptide-induced head group orientation in negatively charged and bacterial membranes, we acquired 31P NMR spectra of POPG and E. coli total lipid bilayers. The 31P NMR spectra of mechanically aligned POPG bilayers with varying concentrations of MSI-843 are shown in Fig. 6B. A comparison of Fig. 6A and B showed that the orientational disorder increased more rapidly in negatively charged POPG membranes than in the zwitterionic POPC bilayers. At P / L = 1 : 33, the 90° peak was already emerging in POPG bilayers while it was absent in POPC membranes even at P / L = 1 : 20. This indicated a preferential interaction of MSI-843 with negatively charged membranes.

E. coli membrane is rich in PE lipids (PE lipids 57.5%, PG lipids 15.1%, cardiolipin 9.8% and other lipids 17.6% w/w) and also negatively charged. The 31P NMR spectrum of aligned bilayers formed of E.coli total lipids displayed a predominant 0° peak at ∼ 26.0 ppm (Fig. 6C). Incorporation of 1, 3, and 5 mol% MSI-843 resulted in the appearance of the 908 peak with an intensity increasing with the concentration of MSI-843. Spectral integration showed that the peptide-induced orientational disorders in E. coli total lipids (Fig. 6C) and POPG bilayers (Fig. 6B) are similar. Thus, MSI-843 appears to perturb selectively the negatively charged bilayers.

3.6. Curvature strain

A combination of 31P NMR and differential scanning calorimetry was used to investigate the ability of MSI-843 to induce curvature strain in lipid bilayers. 31P spectra of aligned E. coli total lipid bilayers at various temperatures are given in Fig. 7. 31P NMR spectra of oriented bilayers of pure E. coli total lipids indicate that the lipids are in lamellar phase at 35 °C (Fig. 7(A)). However, the spectrum at 50 °C showed a peak ∼5 ppm (Fig. 7(B)), indicating the formation of inverted hexagonal phase [6]. On the other hand, the E. coli total lipids containing 3mol% MSI-843 remained in the Lα phase up to 70 °C (Fig. 7(C)), but underwent the Lα to HII phase transition above 70 °C and displayed a peak ∼5 ppm characteristic of a hexagonal phase (Fig. 7(D and E)). As shown in Fig. 7(E), the transition to HII phase reached completion only ∼ 80 °C. These results clearly demonstrate the ability of MSI-843 to suppress the Lα to HII phase transition and suggest the induction of significant positive curvature strain in the membrane [6].

Fig. 7.

31P spectra of oriented pure E. coli total lipid membrane bilayers at 35 (A) and 50 °C (B).31P spectra of oriented E. coli total lipid membrane bilayers containing 3 mol% of MSI-843 at (C) 70, (D) 75 and (E) 80 °C.

Using DSC, similar results were obtained but at much lower concentrations of MSI-843 and DiPoPE (Fig. 8). In the absence of MSI-843, DiPoPE underwent the Lα to HII phase transition at ∼43 °C. When MSI-843 was incorporated into DiPoPE at a P / L = 1 : 500, the transition temperature increased by ∼ 2 °C. The transition temperature increased further when more amounts of MSI-843 were incorporated (Fig. 8). At concentrations (3.0 μM) much lower than the MIC against E. coli (12.5 μM), MSI-843 inhibited the Lα to HII phase transition of DiPoPE.

Fig. 8.

DSC thermograms of DiPoPE MLVs containing (A) 0, (B) 0.2, and (C) 0.4 mol% MSI-843. The rates of heating and cooling were 1 °C/min.

4. Discussion

Different strategies have been utilized to improve the potency and expanding the activity spectrum of antimicrobial peptides [2,3]. They include identification of the minimal fragment for activity, substitution of specific residues to improve activity, total or partial replacement by unusual and d-amino acids, use of retro- and retroenantiomeric analogs, cyclization and linearization of natural peptide antibiotics. Fatty acylation of antimicrobial peptides have recently been explored to improve the spectrum of antimicrobial activity [19,21-23,39].

For the present study, the decapeptide MSI-843 was used as a template to evaluate the biophysical parameters required for the activity against representative bacteria and fungi. MSI-843 shows activity against both bacteria and fungi (Table 1). It also permeabilizes the bacterial outer membrane and anionic model membrane (Figs. 1 and 2). Although several killing mechanisms other than membrane permeabilization have been proposed for antibiotic peptides [4,5,7,35,40], in the case of MSI-843, membrane permeabilization appears to be the essential step in eliciting the antimicrobial activity. The discrepancy between the observed MIC (Table 1) and the concentrations needed for outer membrane permeabilization (Fig. 1) indicates a role for other factors in killing the bacterium. The ability of MSI-843 to induce leakage from negatively charged POPC / POPG (3 : 1) vesicles (Fig. 2) suggests that MSI-843 permeabilizes both outer and inner membranes of bacteria at MIC.

The CD data suggests that the peptide part of MSI-843 folds into an α-helix upon binding to the lipid membrane (Fig. 3A, trace b). However, the strong band at ∼ 207 nm and the low positive ellipticity values below 204 nm suggest the existence of both α-helix and unordered conformations. Such conformational transitions upon binding to lipid membranes have been observed for several other antimicrobial lipopeptides [19-23]. Helical wheel projection of MSI-843 displays the segregation of hydrophilic and hydrophobic amino acids along the α-helix resulting in an amphipathic structure (Fig. 3B). In the case of antimicrobial magainins, random coil to α-helix conformational transition has been shown to provide the driving force for the insertion of peptide into the lipid membranes [37]. The helix formation of magainin analogs was found to involve an enthalpy change of −0.7 kcal/mol per residue and to contribute −0.14 kcal/mol per residue to the total free energy of binding [37]. A qualitative analysis of enthalpy of binding reaction for POPC SUVs, reveals that the helix formation dominates the binding enthalpy of MSI-843. In the case of MSI-843, the mean helix content is 0% in buffer and 37% in the membrane-bound state at 25 °C. Thus, the contribution of helix formation to the binding enthalpy is −2.59 kcal/mol [−0.7 kcal/mol × 0.37 (helicity) ×10 (residues)], and accounts for ∼ 69% of the observed enthalpy of binding (ΔH = −3.63 kcal/mol). The remaining 31% of the binding enthalpy (−1.17 kcal/mol) must be accounted for insertion of the N-terminal octyl and aliphatic side chains into the POPC bilayer. Thus, it seems likely that helix formation in the presence SUVs provides the driving force for membrane insertion. However, considering the low binding enthalpy associated with membrane insertion (−1.17 kcal/mol), the extent of damage MSI-843 might inflict to POPC membrane appears to be lesser when compared with magainins.

2H NMR experiments were used to measure the peptide-induced effect on the hydrophobic core of lipid bilayers. Addition of MSI-843 decreases the order parameter in a concentration dependent manner (Fig. 5). The extent of decrease in the order parameter is maximum for the CD2 groups closer to the head group region and decreases along the acyl chain towards a minimum for the other end of the chain. These observations suggest that the peptide binding increases the disorder in the hydrophobic region of POPC bilayers with a maximal disorder closer to the glycerol backbone of the lipid. Negligible changes are observed in the order parameters of CD2 groups near the lower end of the lipid (carbons 14 and above). This is because the hydrophobic core near the terminal methyl group of the bilayer is highly disordered even in the absence of the peptide and therefore, the peptide-induced disorder appears to be negligible. These observations are consistent with the bilayer surface orientation of the peptide [35]. This prediction is consistent with the observed 31P NMR data (Fig. 6).

According to the toroidal pore model of lipid bilayer disruption by antimicrobial peptides, the formation of toroidal peptide–lipid complex imparts a positive curvature strain in the lipid bilayer [41]. It is evident from Figs. 6 and 7 that MSI-843 has the ability to interact with lipid head groups and repress the fluid lamellar (Lα) to inverted hexagonal (HII) phase transition of E. coli total lipids. DSC data obtained from DiPoPE also show the inhibition of Lα to HII phase transition (Fig. 8). The lipids with phosphatidyl ethanolamine head group have a tendency to form the inverted hexagonal phase with a negative curvature due to their small head group size relative to the length of the acyl chain. Incorporation of MSI-843 mitigates against the formation of the negatively curved HII phase. This implies the induction of positive curvature strain in the bilayer which stabilizes the Lα phase at higher temperatures (Figs. 7 and 8). Stabilization of Lα phase above the phase transition temperature by antimicrobial peptides has been well documented [6,40,41]. Induction of positive curvature strain is considered as one of the events leading to the formation of toroidal peptide–lipid pore complex [40,41], in which the helix axis of peptide molecules is approximately perpendicular to the lipid bilayer normal. Lamellar phase spectra observed from MLVs containing MSI-843 (data not shown) at various concentrations (up to 10 mol%) suggest that the peptide does not function via detergent-type micellization mechanism. However, aligned POPC bilayers containing a high concentration of the peptide (>10 mol%) exhibited a peak near 5 ppm suggesting the formation of peptide-induced normal hexagonal phase (data not shown) as reported for MSI-78 [40].

Although MSI-843 is helical and amphipathic, it has only ten amino acids and therefore cannot span the bilayer to form a transmembrane channel [36]. Therefore, it is likely that MSI-843 forms a peptide–lipid complex in which the peptide lies on the membrane surface in such a way that the hydrophobic side chains and the N-terminal octyl chain are inserted deeply into the membrane. In this orientation, MSI-843 might inflict transient defects in the bilayer acyl chain packing and induce leakage from lipid vesicles (Fig. 2). This model also explains the peptide-induced changes in the head group conformation (Fig. 6) and orientational disorder in the acyl chain (Fig. 5).

5. Conclusion

Modification of antimicrobial peptides with acyl chains has the potential for improvement in activity. Our results on MSI-843 are similar to the data on LF12 lipopeptides, where the best antimicrobial activity was observed with a chain length of C8 for E. coli [25]. The octyl chain at N-terminus and the amphipathic nature of the peptide MSI-843 facilitate the permeabilization of bacterial outer and inner membranes. Both electrostatic interactions, especially between cationic residues of MSI-843 and phosphate groups of lipids, and hydrophobic interactions between the acyl chain of MSI-843 and the lipid chains contribute to membrane destabilization. NMR data clearly rule out the formation of non-lamellar lipid structures and are consistent with toroidal-type pore mechanism. Combination of all the experimental data reported in this paper suggests the formation of a lipid–peptide complex resulting in a transient pore as a plausible mechanism for the membrane permeabilization and antimicrobial activity of MSI-843. Since MSI-843 shows no hemolytic activity at MIC, and exhibits only about 6% hemolysis at 100 μg/mL (∼ .3 times higher than the MIC), the biophysical properties reported in this study will be useful in designing membrane specific antimicrobial peptides.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the funds from NIH (AI054515). This work benefited from discussions with Dr. Lee Maloy.

Abbreviations:

- CSA

chemical shift anisotropy

- CD

circular dichroism

- DiPoPE

1,2-dipalmitoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphotydylethanolamine

- DSC

differential scanning calorimetry

- HI

normal hexagonal phase

- HII

inverted hexagonal phase

- ITC

isothermal titration calorimetry

- Lα

fluid lamellar phase

- MIC

minimum inhibitory concentration

- MLVs

multilamellar vesicles

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- O

ornithine

- Oct

octanoyl

- POPC

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine

- POPC-d31

1-d31-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine

- POPG

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylglycerol

- POPE

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylethanolamine

- SUVs

small unilamellar vesicles

References

- 1.Zasloff M. Antimicrobial peptides of multi-cellular organisms. Nature. 2002;415:389–395. doi: 10.1038/415389a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Devine DA, Hancock REW. Cationic peptides: distribution and mechanisms of resistance. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2002;8:703–714. doi: 10.2174/1381612023395501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maloy WL, Kari UP. Structure–activity studies on magainins and other host defense peptides. Biopolymers. 1995;37:105–122. doi: 10.1002/bip.360370206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsuzaki K. Why and how are peptide–lipid interactions utilized for self-defense? Magainins and tachyplesins as archetypes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1462:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00197-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shai Y. From innate immunity to de-novo designed antimicrobial peptides. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2002;8:715–725. doi: 10.2174/1381612023395367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henzler Wildman KA, Lee D-K, Ramamoorthy A. Mechanism of lipid bilayer disruption by the human antimicrobial peptide, LL-37. Biochemistry. 2003;42:6545–6558. doi: 10.1021/bi0273563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hallock KJ, Lee DK, Omnaas J, Mosberg HI, Ramamoorthy A. Membrane composition determines pardaxin's mechanism of lipid bilayer disruption. Biophys. J. 2002;83:1004–1013. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75226-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Binder H, Lindblom G. A molecular view on the interaction of the Trojan peptide penetratin with the polar interface of lipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 2004;87:332–342. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.034025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Denning DW. Echinocandins and pneumocandins—a new antifungal class with a novel mode of action. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1997;40:611–614. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.5.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ofek L, Cohen S, Rahmani R, Kabha K, Tamarkin D, Herzig Y, Rubinstein E. Antibacterial synergism of polymyxin B nonapeptide and hydrophobic antibiotics in experimental Gram-negative infections in mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1994;38:374–377. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.2.374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alborn WE, Allen NE, Preston DA. Daptomycin disrupts membrane potential in growing Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1991;35:2282–2287. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.11.2282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Auvin-Guette C, Rebuffat S, Prigent Y, Bodo B. Trichogin A IV, an 11-residue lipopeptaibol from Trichoderma longibrachiatum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:2170–2174. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toniolo C, Crisma M, Formaggio F, Peggion C, Epand RF, Epand RM. Lipopeptaibols, a novel family of membrane active, antimicrobial peptides. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2001;58:1179–1188. doi: 10.1007/PL00000932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bender CL, Alarcon-Chaidez F, Gross DC. Pseudomonas syringae phytotoxins: mode of action, regulation, and biosynthesis by peptide and polyketide synthetases. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1999;63:266–292. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.2.266-292.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunphy JT, Linder ME. Signalling functions of protein palmitoylation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1436:245–261. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(98)00130-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Resh MD. Fatty acylation of proteins: new insights into membrane targeting of myristoylated and palmitoylated proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1451:1–16. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(99)00075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johansson J. Structure and properties of surfactant protein C. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1408:161–172. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(98)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Denning DW. Echinocandins and pneumocandins—a new antifungal class with a novel mode of action. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1997;40:611–614. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.5.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lockwood NA, Haseman JR, Tirrell MV, Mayo KH. Acylation of SC4 dodecapeptide increases bactericidal potency against Gram-positive bacteria, including drug-resistant strains. Biochem. J. 2004;378:93–103. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Avrahami D, Shai Y. Bestowing antifungal and antibacterial activities by lipophilic acid conjugation to d,l-amino acid-containing antimicrobial peptides: a plausible mode of action. Biochemistry. 2003;42:14946–14956. doi: 10.1021/bi035142v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chu-Kung AF, Bozzelli KN, Lockwood NA, Haseman JR, Mayo KH, Tirrell MV. Promotion of peptide antimicrobial activity by fatty acid conjugation. Bioconjug. Chem. 2004;15:530–535. doi: 10.1021/bc0341573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wakabayashi H, Matsumoto H, Hashimoto K, Teraguchi S, Takase M, Hayasawa H. N-acylated and d enantiomer derivatives of a nonamer core peptide of lactoferricin B showing improved antimicrobial activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1267–1269. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.5.1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mak P, Pohl J, Dubin A, Reed MS, Bowers SE, Fallon MT, Shafer WM. The increased bactericidal activity of a fatty acid-modified synthetic antimicrobial peptide of human cathepsin G correlates with its enhanced capacity to interact with model membranes. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2003;21:13–19. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(02)00245-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bellamy W, Takase M, Wakabayashi H, Kawase K, Tomita M. Antibacterial spectrum of lactoferricin B, a potent bactericidal peptide derived from the N-terminal region of bovine lactoferrin. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1992;73:472–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1992.tb05007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Majerle A, Kidric J, Jerala P. Enhancement of antibacterial and lipopolysaccharide binding activities of a human lactoferrin peptide fragment by the addition of acyl chain. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2003;51:1159–1165. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rustici A, Velucchi M, Faggioni R, Sironi M, Ghezzi P, Quataert S, Green B, Porro M. Molecular mapping and detoxification of the lipid A binding site by synthetic peptides. Science. 1993;259:361–365. doi: 10.1126/science.8420003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duwe AK, Rupkar CA, Horsman GB, Vas SI. In vitro cytotoxicity and antibiotic activity of polymyxin B nonapeptide. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1986;30:340–341. doi: 10.1128/aac.30.2.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slavik J. Anilinonaphthalene sulfonate as a probe of membrane composition and function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1982;694:1–25. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(82)90012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tan A, Ziegler A, Steinbauer B, Seelig J. Thermodynamics of sodium dodecyl sulfate partitioning into lipid membranes. Biophys. J. 2002;83:1547–1556. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)73924-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rohl CA, Baldwin RL. Comparison of NH exchange and circular dichroism as techniques for measuring the parameters of the helix-coil transition in peptides. Biochemistry. 1997;36:8435–8442. doi: 10.1021/bi9706677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thennarasu S, Nagaraj R. Design of 16-residue peptides possessing antimicrobial and hemolytic activities or only antimicrobial activity from an inactive peptide. Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 1995;46:480–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1995.tb01603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hallock KJ, Wilderman KH, Lee D-K, Ramamoorthy A. An innovative procedure using a sublimable solid to align lipid bilayers for solid-state NMR studies. Biophys. J. 2002;82:2499–2503. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75592-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Washburn EW, West CJ, Hull C. International critical, tables of numerical data, physics, chemistry, and technology. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1926. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bloom M, Davis JH, Mackay AL. Direct determination of the oriented sample NMR spectrum from the powder spectrum for systems with local axial symmetry. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1981;80:198–202. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henzler Wildman KA, Martinez GV, Brown MF, Ramamoorthy A. Perturbation of the hydrophobic core of lipid bilayers by the human antimicrobial peptide LL-37. Biochemistry. 2004;43:8459–8469. doi: 10.1021/bi036284s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Killion JA, von Heijne G. How proteins adapt to a membrane–water interface. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000;25:429–434. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01626-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weiprecht T, Apostolov O, Beyermann M, Seelig J. Thermodynamics of the alpha-helix-coil transition of amphipathic peptides in a membrane environment: implications for the peptide-membrane binding equilibrium. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;294:785–794. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thennarasu S, Nagaraj R. Solution conformations of peptides representing the sequence of the toxin pardaxin and analogues in trifluoroethanol–water mixtures: analysis of CD spectra. Biopolymers. 1997;41:635–645. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(199705)41:6<635::AID-BIP4>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Epand RM. Biophysical studies of lipopeptide-membrane interactions. Biopolymers. 1997;43:15–24. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(1997)43:1<15::AID-BIP3>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hallock KJ, Lee D-K, Ramamoorthy A. MSI-78, an analogue of the magainin antimicrobial peptides, disrupts lipid bilayer structure via positive curvature strain. Biophys. J. 2003;84:3052–3060. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)70031-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matsuzaki K, Sugishita K, Ishibe N, Ueha M, Nakata S, Miyajima K, Epand RM. Relationship of membrane curvature to the formation of pores by magainin 2. Biochemistry. 1998;37:11856–11863. doi: 10.1021/bi980539y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]