Abstract

Viral gene therapy has exceptional potential as a specifically tailored cancer treatment. However, enthusiasm for cancer gene therapy has varied over the years, partly owing to safety concerns after the death of a young volunteer in a clinical trial for a genetic disease. Since this singular tragedy, results from numerous clinical trials over the past 10 years have restored the excellent safety profile of adenoviral vectors. These vectors have been extensively studied in phase I and II trials as intraprostatically administered agents for patients with locally recurrent and high-risk local prostate cancer. Promising therapeutic responses have been reported in several studies with both oncolytic and suicide gene therapy strategies. The additional benefit of combining gene therapy with radiation therapy has also been realized; replicating adenoviruses inhibit DNA repair pathways, resulting in a synergistic sensitization to radiation. Other, nonreplicating suicide gene therapy strategies are also significantly enhanced with radiation. Combined radiation/gene therapy is currently being studied in phase I and II clinical trials and will likely be the first adenoviral gene therapy mechanism to become available to urologists in the clinic. Systemic gene therapy for metastatic disease is also a major goal of the field, and clinical trials are currently under way for hormone-resistant metastatic prostate cancer. Second- and third-generation “re-targeted” viral vectors, currently being developed in the laboratory, are likely to further improve these systemic trials.

Key words: Prostate cancer, Adenovirus, Gene therapy, Radiation therapy, Suicide gene therapy, Oncolytic virus, Conditionally replicating adenovirus (CRAD), Re-targeting

Prostate cancer is unique in many ways when compared with other solid tumor malignancies, most notably in its slow growth rate.1 With only approximately 5% of prostatic tumor cells dividing (in S-phase) at any one time, it is not surprising that chemotherapeutic strategies have not produced major improvements in patient survival.2,3 Although hormone-ablative therapies are decidedly effective, they are not curative. Adenoviral vectors offer an alternative, highly tailored therapy that can take advantage of the distinct qualities of prostate epithelial/cancer cells and can be safely and effectively combined with radiation and chemotherapy.

Why Prostate Cancer?

The promise of viral gene therapy lies in the ability to design a highly specific treatment that takes advantage of tissue- or disease-specific genetics. Tissue-specific gene promoters offer a means to broadly deliver a therapeutic virus that will become activated only in certain cell types (transcriptional targeting). With estimates of more than 200 prostate-specific genes, there are numerous options to transcriptionally target prostate cells.4,5 Additional cancer-specific gene mutations, such as p53,6–8 or cancer-related gene overexpression, such as the prostate-specific membrane antigen,9 offer added targets for tissue-restrictive therapy. Multiple adenoviral vectors are available to incorporate small (2–8 kilobases [kb]) or large (>20 kb) transgene constructs to achieve this specificity (discussed below). Furthermore, adenoviruses affect both dividing and nondividing cells, a valuable attribute for a prostate cancer therapy. The viral genome is non-integrating; therefore, permanent virally induced genomic damage is of little concern. Additionally, because the prostate is an accessory gland, there is no need to differentiate between normal and cancerous prostate tissues.

Most clinical trials of adenoviral therapies for prostate cancer involve direct prostatic injection. The anatomic location and the existing brachytherapy templates have made locally recurrent prostate cancer an ideal candidate for clinical trials. Direct injection also minimizes antiviral immune responses, a potential limiting factor in systemically applied gene therapy. Finally, the added value of serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) as a surrogate marker for therapeutic effect has played a role in drawing the interest of gene therapists.

Pathogenesis of Adenovirus

Adenoviruses were initially identified in the early 1950s as infectious agents responsible for outbreaks of acute respiratory disease in military recruits.10 The virus was first characterized in cultures of adenoid tissue, eventually leading to the name adenovirus.11 Currently, 49 human adenoviral serotypes have been identified, each classified into 1 of 6 subclasses characterized by its ability to agglutinate red blood cells.12 The main serotypes applied to gene therapy are serotypes 2 and 5, which belong to subclass C, and more recently the subclass B serotype 35.

Clinically, adenoviral infections are common and generally mild. Nearly 100% of adults have antibodies against multiple adenoviral serotypes. Infection is most commonly associated with respiratory disease, but adenovirus can also cause conjunctivitis, infantile gastroenteritis, cystitis, and rash illness.

Adenoviral Life Cycle

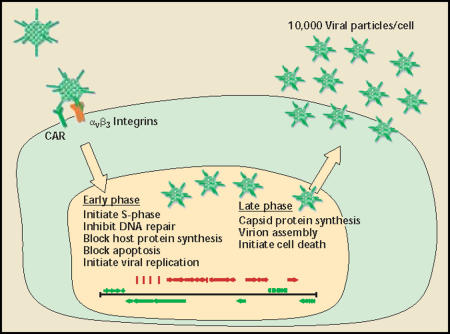

Adenoviruses are small (approximately 100 nm), non-enveloped, linear double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid (dsDNA) viruses encapsulated in an icosahedral protein shell. Three major capsid proteins make up the exterior shell: hexon, penton, and fiber (Figure 1). Adenoviral infection begins with the interaction of the knob portion of the adenoviral fiber protein with the cellular receptor CAR (coxsackie adenovirus receptor).13–16 Viral internalization is triggered by interaction of the viral penton proteins with epithelial integrins,17 resulting in receptor-mediated endocytosis into clathrin-coated pits.18 The virus escapes the early endosome and is transported to the nucleus. Once in the nucleus, the viral genome escapes the remaining capsid proteins and remains episomal (non-integrating) while early viral gene expression begins (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Adenoviral particles. Three major coat proteins make up the icosahedral adenovirus particle. The most abundant coat protein is hexon. which makes up 240 capsomeres per article. Twelve fiber trimers are loated at each icosahedral vertex. The knob portion of fiber is responsible for cell binding through the cellular receptor CAR. At the base of each fiber trimer is the penton capsomere. An exposed RGD motif in each of the 5 penton molecules binds cellular integrins and triggers internalization. CAR, coxsackie adenovirus receptor; RGD, Arg-Gly-Asp.

Figure 2.

Adenoviral life cycle. Adenoviral infection begins with a binding event between the viral fiber knob and the cellular receptor, CAR. A second binding event between viral penton RGD and cellular integrins triggers internalization through receptor-mediated endocytosis. The virus escapes early endosomes and enters the nucleus. Viral gene expression is sequential, starting with early genes (green) and ending with late genes (red). Early genes initiate cellular S-phase, block apoptosis, block host messenger ribonucleic acid transport and translation, inhibit deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) repair pathways, and initiate viral DNA replication. After viral DNA replication, late genes are expressed, leading to capsid protein synthesis, nuclear viral assembly, and cell death. CAR, coxsackie adenovirus receptor; RGD, Arg-Gly-Asp.

Viral gene expression is sequential, beginning with the immediate early genes E1–E4 and followed by the late genes L1–L5, which are transcribed as a single large alternatively spliced transcript. The earliest genes, E1A and E1B, drive the cell into S-phase by inhibiting Rb and p53 (among other genes), respectively. Early gene products also inhibit DNA repair pathways, initiate viral DNA replication, block interferon responses, inhibit apoptosis, block host cell ribonucleic acid (RNA) transport out of the nucleus, and preferentially transport viral messenger RNAs (mRNAs) to the cytoplasm (see Shenk 2001 for review).12 After viral DNA replication, late gene transcription and translation begins, resulting in production of capsid and assembly proteins. The capsid proteins translocate back into the nucleus for viral assembly, and progeny virus is released approximately 24 to 48 hours after infection. Approximately 10,000 viral particles are produced per cell in optimal conditions.

Adenoviral Gene Therapy Vectors

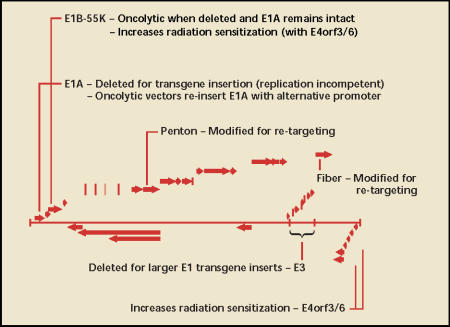

First-generation adenoviral vectors are replication attenuated by removal of the E1A gene (Figure 3).19 Without the E1A gene, viral genes are not expressed at high enough levels for effective replication and packaging, leaving the recombinant virus as a simple carrier of therapeutic genes. Recombinant constructs are placed in the E1 locus and generally consist of a small gene promoter and therapeutic transgene. Additional viral genes, including E1B and E3, can be removed so that larger transgenes can be inserted. More recently, so-called second-generation vectors have even more viral genes removed to allow for larger transgene packages and to minimize host immune response to viral gene products. In some high-capacity vectors, called “gutless” vectors, all viral open reading frames are removed.

Figure 3.

Adenoviral vector anatomy. The 36-kilobase double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid (dsDNA) adenoviral genome is shown with open reading frames represented by block arrows. The E1A gene is the first gene synthesized and controls viral replication through a transcriptional cascade. E1A is replaced by fusions of foreign promoters and therapeutic genes in replication-attenuated vectors, or is re-inserted under the control of a foreign promoter in conditionally replicating vectors. E1B-55K can also be deleted to generate oncolytic vectors, previously thought to be reliant on p53 mutation. The E3 gene can be deleted to allow for larger transgene inserts. Three genes, E1B-55K, E4orf3, and E4orf6, participate in blocking dsDNA repair, leading to radiation sensitization. Two capsid encoding genes, fiber and penton, can be altered for transductional targeting.

Recombinant adenovirus can be produced to very high titers (1013 particles/mL) when compared with other viral gene therapy systems. This production requires packaging lines containing viral genes to complement those deleted in the vector.20–22 Rare recombination events can occur during packaging, resulting in low levels of wild-type or similar virus. Therefore, new recombination-deficient packaging lines have been developed to minimize these contaminants.23 Some packaging cells must also be resistant to the designed therapy. For example, we have designed a prostate-specific diphtheria toxin (DT)-expressing virus that requires production in a specialized DT-resistant cell line.24

Several options are available when designing a viral cancer therapeutic agent: 1) repair mutant pathways associated with a certain cancer (corrective gene therapy); 2) cause cell death of infected and neighboring cells by expression of a toxin, a stimulator of apoptosis, or prodrug-activating gene (suicide gene therapy); 3) recruit the immune system by expression of immune-stimulatory genes (immuno gene therapy); or 4) design the virus to conditionally replicate and lyse only tumor cells (oncolytic gene therapy). All of these strategies have been tested in phase I/II clinical trials for locally recurrent and/or high-risk prostate cancers (Table 1). However, for the purpose of this review, we will briefly review only a few oncolytic and suicide gene therapy strategies and their application to preclinical and clinical prostate cancer. We place special emphasis on the benefits of combining adenoviral gene therapy with radiation, because urologists will likely play a key role in administering these gene therapies in combination with brachytherapy in large multicenter clinical trials.

Table 1.

Clinical Trials of In Situ Adenoviral Gene Therapy Single Agents for Prostate Cancer

| NIH No. | Phase | Indication | Promoter | Therapeutic |

| 9601-144 | I | Local recurrent | RSV | HSV-TK |

| 9705-187 | I | Neoadjuvant | RSV | HSV-TK |

| 9706-192 | I | Local recurrent | CMV | p53 |

| 9710-217 | I | Neoadjuvant | CMV | p53 |

| 9801-229 | I | Neoadjuvant | RSV | HSV-TK |

| 9802-236 | I | Local recurrent | PSA/PSE | Replication (E1A) |

| 9812-276 | I | Metastatic or recurrent | Murine OC | HSV-TK |

| 9906-321 | I | Local recurrent | CMV | Replication + CD/HSV-TK |

| 9909-338 | I | Neoadjuvant | RSV | CDKN2A |

| 9910-344 | I/II | Local recurrent | Rat probasin and PSA/PSE | Replication (E1A and E1B) |

| 0010-426 | I | Metastatic | Murine OC | Replication (E1A) |

| 0010-428 | I | Neoadjuvant | CMV | Replication + CD/HSV-TK |

| 0101-449 | I | Local recurrent | CMV | IL-12 |

| 0203-517 | I | Neoadjuvant | CMV | IFN-β |

| 0204-533 | I | Local recurrent | CMV | NIS |

| 0309-601 | I | Local recurrent | RSV | IL-12 |

| 0309-603 | I | Neoadjuvant | CMV | TRAIL |

NIH, National Institutes of Health; RSV, Rouse sarcoma virus (constitutively active); HSV-TK, herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase; CMV, cytomegalovirus (constitutively active); PSA/PSE, prostate-specific antigen promoter/enhancer;CDKN2A, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A; OC, osteocalcin; IL-12, interleukin 12; IFN-β, interferon-β; NIS, sodium iodide symporter; TRAIL, tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand. Local recurrent, after radiation therapy; Neoadjuvant, before radical prostatectomy, Data derived from http://www.gemcris.od.nih.gov.

Oncolytic Gene Therapy

Two strategies have been applied to develop oncolytic adenoviral vectors: 1) to use cancer- or tissue-specific promoters to drive immediate early viral genes; or 2) to mutate viral genes responsible for inactivating cellular tumor suppressors that are often mutated in cancer. The first tissue-specific oncolytic adenovirus, CG7060 (formerly CN706 and CV706), was designed for the treatment of prostate cancer.25 By placing the E1A gene under the control of the PSA promoter and enhancer, viral replication was limited to prostate epithelial and cancer cells. A subsequent vector, CG7870 (formerly CV787), applied 2 prostate-specific promoters to control both the viral E1A and E1B genes.26 Both vectors have entered clinical trials as intraprostatically injected agents for locally recurrent and advanced local disease, both alone and in combination with radiation therapy.

In the initial clinical trial, 1 × 1011 to 1 × 1013 viral particles of CG7060 were injected intraprostatically at between 20 and 80 sites,27 on the basis of a 1 cm3 calculated viral diffusion limitation.28 No grade 3 or 4 toxicities were reported, and the maximum tolerable dose was not reached. This report provided further evidence of the excellent safety profiles of attenuated or conditionally replicating adenoviruses (CRADs) when injected directly into the prostate, even with doses near those that caused the unfortunate death of the young volunteer at the University of Pennsylvania (3.8 X 1013 particles).29 The extensive clinical testing of CRAD vectors in multiple cancer types has been recently reviewed and reiterates that “no significant respiratory, liver toxicities, or clotting abnormalities attributable to a replication-competent Ad vector have been reported in clinical trials published to date.”30

The preliminary reports of efficacy in the CG7060 trial were encouraging.27 Viral replication was demonstrated by nuclear viral particles in electron micrographs of prostatic biopsy specimens and by a second burst of virus detected in the serum 2 to 8 days after infection. Five patients receiving the highest treatment doses had decreases in serum PSA of greater than 50%. The subsequent vector, CG7870, demonstrated still greater efficacy in animal models, leading to complete elimination of tumors, even when administered intravenously (IV) through the tail vein.26 CG7870 is currently in clinical trials as an in situ-delivered agent, either alone or in combination with radiation, for the treatment of local disease. Recently, 2 trials have also begun evaluating CG7870 as an IV-administered systemic treatment for advanced hormone-refractory prostate cancer, both as a single agent and in combination with docetaxel (a combination shown to be synergistic in animal models).31 Results of in situ and IV-administered CG7870 are still accumulating and have yet to be reported in the literature.

Suicide Gene Therapy

Suicide gene therapy vectors, by definition, deliver a toxic genetic package, leading to the death of infected cells and potentially of neighboring cells. As noted above, we have constructed a suicide gene therapy in which DT is specifically expressed by a prostate-specific gene promoter in an E1-deleted adenovirus.24 DT has been shown to cause prostate cancer cell death by both apoptotic and non-apoptotic pathways.32 Our virus, Ad5PSE-DT-A, demonstrated excellent tumor-killing ability in animal models; however, it has not been translated to the clinic, due to production, safety, and toxicity concerns.

The most highly studied suicide gene therapy strategy for cancer has been adenoviral expression of the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSV-TK) followed by treatment with the nontoxic prodrug gancyclovir (GCV). Expression of HSV-TK leads to GCV phosphorylation and subsequent genomic incorporation, causing termination of host DNA synthesis and cell death. The HSV-TK strategy is especially appealing because neighboring, noninfected cells can also be killed by transfer of activated GCV through gap junctions and phagocytosis of apoptotic vesicles.33,34

A non-transcriptionally targeted virus, ADV/RSV-TK,35 was the first adenoviral gene therapy clinically tested in prostate cancer.36 Patients received between 1 × 108 and 1 × 1011 infectious units by intraprostatic injection, followed by 14 days of intravenous GCV (twice daily). Safety was clearly demonstrated. Only a few patients experienced low-level, reversible toxicities, even with repeat injections.37 Additionally, there was no evidence of aberrant viral replication or shedding. Some patients receiving the highest treatment levels had greater than 50% decreases in serum PSA for more than 6 weeks. The virus also seems to induce a local immune response, as evidenced by increased CD8+ T cells, which possibly enhances the therapeutic effect.38

Combined Oncolytic and Suicide Gene Therapy

Freytag and colleagues39 have designed an adenoviral strategy that combines oncolytic and suicide gene therapy. Ad5-CD/TKrep contains a truncated E1B-55K gene, which codes for the viral protein that inactivates the p53 tumor suppressor gene. It was hypothesized that viruses lacking E1B-55K preferentially replicate in cancer cells with mutant p53 genes,40 a quality common to advanced prostate cancers.6–8 However, it was later shown that replication of such viruses is not dependent on p53 status, but rather on efficiency of expressing late viral genes.41 Regardless of the mechanism, this strategy of oncolysis seems to be selective for tumor cells.

Ad5-CD/TKrep also expresses a dual prodrug-activating fusion protein, cytosine deaminase-thymidine kinase, that can both phosphorylate GCV and deaminate 5-fluorocytosine (5-FC) to the potent thymidylate synthase inhibitor 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). Both products inhibit DNA synthesis and cause cell death. The combination of intraprostatically delivered Ad5-CD/TKrep followed by up to 2 weeks of GCV and 5-FC treatment was found to be safe in a phase I study, with no dose-limiting toxicities or maximum tolerable dose of virus.42 Efficacy was demonstrated in some patients by decreases in serum PSA of up to 60%.

Benefits of Combining Gene Therapy and Radiation

Ionizing radiation causes severe DNA damage in the form of single- and double-stranded breaks, resulting in cell death by either programmed cell death (apoptosis) or so-called reproductive death. Cells recognize double-strand breaks through the tri-component DNA protein kinase complex (DNA-PK), which initiates 2 cellular repair pathways: homologous recombination and nonhomologous end joining.43 Because the adenovirus genome is linear dsDNA, it must evade recognition by DNA-PK to avoid concatamerization (ie, selfligation). To achieve this, 2 viral proteins, E4orf3 and E4orf6, bind to and inhibit the DNA-PK complex.44 Furthermore, the dsDNA multiprotein repair complex of Mre11, Rad50, and NBS1 is reorganized and degraded by the cooperative efforts of E4orf3/6 and E1B-55K.45 Because it had been shown that inhibition of the DNA-PK pathway sensitizes cells to ionizing radiation,46,47 several groups have investigated and confirmed that adenovirus can also trigger radiosensitivity. For example, the prostate-specific CRAD, CG7060, produced synergistic tumor cell death when combined with radiation therapy in prostate cancer xenograft models.48

Radiation also enhances many suicide gene therapy strategies, including CD + 5-FC and HSV-TK + GCV. 5-FU had previously been reported to enhance radiation effects in prostate cell lines.49 HSV-TK + GCV plus radiation also demonstrated additive effects by reducing both tumor volume and establishment of lung metastases in the RM-1 prostate cancer mouse model.50 The oncolytic suicide gene therapy vector Ad5-CD/TKrep was originally described for application in a trimodal approach combining viral replication, suicide gene therapy, and radiation.39 As expected, this combination enhanced radiation-induced cell death, both in vitro and in vivo.51 Furthermore, radiation might also increase the “bystander effect” by allowing activated prodrugs to transfer across radio-damaged cell membranes. It has also been shown that radiation increases adenoviral infection efficiency.52

The combination of adenoviral gene therapy and radiation therapy, both in the form of external beam and as radioactive seeds, has reached phase I/II clinical trials for prostate cancer (Table 2). It seems that adenoviral injection does not significantly add to the toxicity of radiation therapy; therefore, if efficacy can be demonstrated, this combination might soon be available in the clinic.

Table 2.

Clinical Trials Combining Radiation and Adenoviral Gene Therapy for Prostate Cancer

| NIH No. | Phase | Indication | Promoter | Therapeutic |

| 9906-324 | I/II | High-risk local | RSV | HSV-TK |

| 0010-418 | II | Local recurrent | CMV | p53 |

| 0101-450 | II | High-risk local | Rat probasin and PSA/PSE | Replication (E1A and E1B) |

| 0104-464 | I | High-risk local | CMV | Replication + CD/HSV-TK |

| 0111-509 | I/II | High-risk local | PSA/PSE | Replication (E1A) |

| 0302-572 | I/II | High-risk local | PSA/PSE | Replication (E1A) |

| 0307-590 | I/II | High-risk local | CMV | Replication + CD/HSV-TK |

| 0307-597 | I/II | Local recurrent | CMV | Replication + CD/HSV-TK |

NIH, National Institutes of Health; RSV, Rouse sarcoma virus (constitutively active); HSV-TK, herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase; CMV, cytomegalovirus (constitutively active); PSA/PSE, prostate-specific antigen promoter/enhancer; Local recurrent, after radiation therapy. Data derived from http://www.gemcris.od.nih.gov.

Re-Targeting: The Future of Gene Therapy

The ultimate application of viral cancer gene therapy is as a systemic agent that can selectively infect and kill metastatic tumor cells. Although most clinical trials of adenoviral vectors have used in situ delivery, some viruses are being studied as IV-administered agents.53 The prostate-specific CRAD, CG7870, is one such vector being studied in this manner, both as a single agent and in combination with docetaxel for advanced hormone-refractory prostate cancer (Table 3). The results of these trials have not been published, but recent presentations at the annual meetings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the American Society of Gene Therapy suggest that CG7870, as an individual agent, might reach metastatic tumors and elicit therapeutic responses as evidenced by decreases in serum PSA.54 Although preliminary and indirect, these results are promising, considering CG7870 was developed with traditional first-generation adenoviral vectors. Recent advances in the next generation of adenoviral vectors have significantly improved their biodistribution. This is accomplished by mutating viral capsid proteins to avoid non-target cell infection and incorporating re-targeting motifs to redirect infection. These strategies have recently been reviewed in the literature55–57; here we briefly discuss some advances.

Table 3.

Clinical Trials of Intravenously Administered Adenoviral Gene Therapy for Prostate Cancer

| NIH No. | Phase | Indication | Promoter | Therapeutic |

| 9910-345 | I/II | HR metastatic | Rat probasin and PSA/PSE | Replication (E1A and E1B) |

| 0101-451 | II | HR metastatic | Rat probasin and PSA/PSE | Replication (E1A and E1B) + docetaxel |

NIH, National Institutes of Health; HR, hormone-refractory; PSA/PSE, prostate-specific antigen promoter/enhancer. Data derived from http://www.gemcris.od.nih.gov.

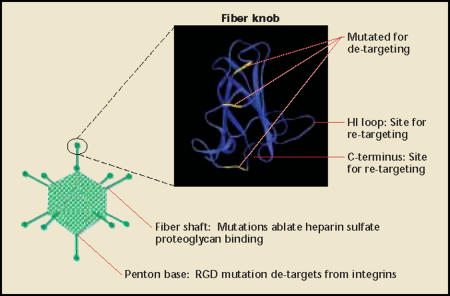

The widespread epithelial expression of the adenoviral receptor (CAR) is a major limitation to systemic therapy. Administered viral doses are quickly depleted by infection of non-target cells, especially in the liver. Because of this, non-transcriptionally targeted vectors are not well suited for systemic therapy. To decrease toxicity and improve therapeutic effect, one must de-target the virus from the natural receptor and re-target infection to an alternative receptor (Figure 3 and Figure 4). This was first demonstrated to be plausible when bifunctional targeting agents were shown to simultaneously bind and block fiber-CAR-mediated infection while re-targeting infection to specific cells.58 Later, it was shown that coding sequences of re-targeting peptides could be genetically incorporated into certain portions of the fiber gene and mediate infection through novel receptors.59,60 Furthermore, mutations of specific codons in the fiber gene can ablate the ability to recognize the cellular receptor, CAR, while still having correct protein folding and assembly into the viral capsid.61–65

Figure 4.

Adenoviral re-targeting. Currently, adenoviral vector re-targeting focuses on three areas: the fiber knob, fiber shaft, and penton base (although others have been described). A fiber knob monomer (generated from MMDB 1398,72,73 modified by 3D molecular viewer [InforMax,® Frederick, MD]) is shown, and sites mutated for ablating CAR binding are highlighted in yellow. Both the HI loop and carboxy-terminus (C-terminus) have been used for incorporation of re-targeting peptides. The combination of fiber knob mutations and penton base RGD mutations has been reported to decrease liver tropism. The fiber shaft contains a heparin sulfate proteoglycan binding domain, mutation of which has also been shown to reduce liver tropism when combined with penton base and fiber mutations. CAR, coxsackie adenovirus receptor; RGD, Arg-Gly-Asp.

Multiple combinations of mutations in the fiber and penton genes, and differential modes of systemic delivery, are showing additional effects on viral biodistribution in animals.66–70 To date, however, there is no consensus regarding the optimal mechanism of de-targeting and re-targeting. Given the preliminary results of IV-administered CG7870, small improvements in re-targeting might be enough to increase therapeutic effect. However, there has yet to be a genetically retargeted adenoviral vector for prostate cells. One approach we are considering is to create such a vector by incorporating prostate-specific membrane antigen-binding peptides into our existing adenoviral vectors.71

Although advances in re-targeting have been impressive in animal models, systemic gene therapy faces other hurdles. Further improvements in viral circulation time, diffusion and spread within a tumor, immune avoidance, and diversification of targeting and therapy (to overcome tumor cell heterogeneity) will likely be required before viruses will be highly effective as single agents. Therefore, the most probable application of adenoviral vectors as systemic therapy will be in combination with existing therapies.

Conclusions

Adenoviral gene therapy vectors have been shown repeatedly to have excellent safety profiles in prostate cancer clinical trials. Preliminary results of efficacy are promising and seem to be dose dependent in many trials. The most promising discovery is the additive and synergistic responses reported from combination with radiation therapy. Clinical trials are under way to evaluate this combination in local recurrent and high-risk local prostate cancers. If efficacy is confirmed, this will likely be the first prostate cancer gene therapy application to reach urologists in the clinic. Meanwhile, advances in gene therapy vector design are beginning to improve biodistribution and might lead to effective systemic treatments for metastatic disease, most likely in combination with other therapies.

Main Points.

For the treatment of prostate cancer, adenoviral vectors offer an alternative, highly tailored therapy that can take advantage of the distinct qualities of prostate epithelial/cancer cells and can be safely and effectively combined with radiation and chemotherapy.

The first tissue-specific oncolytic adenovirus, CG7060, was designed for the treatment of prostate cancer; preliminary reports of efficacy in the CG7060 trial were encouraging, and 5 patients receiving the highest treatment doses demonstrated decreases in serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) of greater than 50%.

A subsequent vector, CG7870, demonstrated still greater efficacy in animal models; CG7870 is currently in clinical trials as an in situ-delivered agent, either alone or in combination with radiation, for the treatment of local disease.

The non-transcriptionally targeted virus ADV/RSV-TK was the first adenoviral gene therapy clinically tested in prostate cancer; safety was clearly demonstrated, and there was no evidence of aberrant viral replication or shedding. Some patients receiving the highest treatment levels showed greater than 50% decreases in serum PSA for more than 6 weeks.

The combination of adenoviral gene therapy and radiation therapy, both in the form of external beam and as radioactive seeds, has reached phase I/II clinical trials for prostate cancer; if efficacy can be demonstrated, this combination might soon be available in the clinic.

The systemic application of adenoviral gene therapy to metastatic disease is limited by the widespread sequestration of the virus to non-target tissues, especially the liver. New strategies are being explored to circumvent the natural biodistribution of the virus and to re-target infection specifically to prostate and prostate cancer cells.

This study was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health Prostate SPORE program, the Robert and Donna Tompkins Foundation, and the Department of Defense Prostate Cancer Research Program, which is managed by the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Steve Freedland for his critical examination and valuable comments in reviewing this article.

References

- 1.Schmid HP, McNeal JE, Stamey TA. Clinical observations on the doubling time of prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 1993;23(suppl 2):60–63. doi: 10.1159/000474708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Visakorpi T, Kallioniemi OP, Paronen IY, et al. Flow cytometric analysis of DNA ploidy and S-phase fraction from prostatic carcinomas: implications for prognosis and response to endocrine therapy. Br J Cancer. 1991;64:578–582. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1991.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kallioniemi OP, Visakorpi T, Holli K, et al. Improved prognostic impact of S-phase values from paraffin-embedded breast and prostate carcinomas after correcting for nuclear slicing. Cytometry. 1991;12:413–421. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990120506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu LL, Su YP, Labiche R, et al. Quantitative expression profile of androgen-regulated genes in prostate cancer cells and identification of prostate-specific genes. Int J Cancer. 2001;92:322–328. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson PS, Clegg N, Eroglu B, et al. The prostate expression database (PEDB): status and enhancements in 2000. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:212–213. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Navone NM, Troncoso P, Pisters LL, et al. p53 protein accumulation and gene mutation in the progression of human prostate carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:1657–1669. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.20.1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bookstein R, MacGrogan D, Hilsenbeck SG, et al. p53 is mutated in a subset of advanced-stage prostate cancers. Cancer Res. 1993;53:3369–3373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brooks JD, Bova GS, Ewing CM, et al. An uncertain role for p53 gene alterations in human prostate cancers. Cancer Res. 1996;56:3814–3822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horoszewicz JS, Kawinski E, Murphy GP. Monoclonal antibodies to a new antigenic marker in epithelial prostatic cells and serum of prostatic cancer patients. Anticancer Res. 1987;7:927–935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hilleman MR, Werner JH. Recovery of new agent from patients with acute respiratory illness. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1954;85:183–188. doi: 10.3181/00379727-85-20825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rowe WP, Huebner RJ, Gilmore LK, et al. Isolation of a cytopathogenic agent from human adenoids undergoing spontaneous degeneration in tissue culture. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1953;84:570–573. doi: 10.3181/00379727-84-20714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shenk T. Adenoviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Fields BN, Howley PM, Griffen DE, editors. Fields Virology. New York: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2001. pp. 2265–2300. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomko RP, Xu R, Philipson L. HCAR and MCAR: the human and mouse cellular receptors for subgroup C adenoviruses and group B coxsackie viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3352–3356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Louis N, Fender P, Barge A, et al. Cell-binding domain of adenovirus serotype 2 fiber. J Virol. 1994;68:4104–4106. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.6.4104-4106.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henry LJ, Xia D, Wilke ME, et al. Characterization of the knob domain of the adenovirus type 5 fiber protein expressed in Escherichia coli. J Virol. 1994;68:5239–5246. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.5239-5246.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bergelson JM, Cunningham JA, Droguett G, et al. Isolation of a common receptor for Coxsackie B viruses and adenoviruses 2 and 5. Science. 1997;275:1320–1323. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5304.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wickham TJ, Mathias P, Cheresh DA, Nemerow GR. Integrins alpha v beta 3 and alpha v beta 5 promote adenovirus internalization but not virus attachment. Cell. 1993;73:309–319. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90231-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varga MJ, Weibull C, Everitt E. Infectious entry 33. pathway of adenovirus type 2. J Virol. 1991;65:6061–6070. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.6061-6070.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Doren K, Hanahan D, Gluzman Y. Infection of eucaryotic cells by helper-independent recombinant adenoviruses: early region 1 is not obligatory for integration of viral DNA. J Virol. 1984;50:606–614. doi: 10.1128/jvi.50.2.606-614.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Louis N, Evelegh C, Graham FL. Cloning and sequencing of the cellular-viral junctions from the human adenovirus type 5 transformed 293 cell line. Virology. 1997;233:423–429. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graham FL, Smiley J, Russell WC, Nairn R. Characteristics of a human cell line transformed by DNA from human adenovirus type 5. J Gen Virol. 1977;36:59–74. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-36-1-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fallaux FJ, Kranenburg O, Cramer SJ, et al. Characterization of 911: a new helper cell line for the titration and propagation of early region 1-deleted adenoviral vectors. Hum Gene Ther. 1996;7:215–222. doi: 10.1089/hum.1996.7.2-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fallaux FJ, Bout A, van der Velde I, et al. New helper cells and matched early region 1-deleted adenovirus vectors prevent generation of replication-competent adenoviruses. Hum Gene Ther. 1998;9:1909–1917. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.13-1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Y, McCadden J, Ferrer F, et al. Prostate-specific expression of the diphtheria toxin A chain (DT-A): studies of inducibility and specificity of expression of prostate-specific antigen promoter-driven DT-A adenoviral-mediated gene transfer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2576–2582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodriguez R, Schuur ER, Lim HY, et al. Prostate attenuated replication competent adenovirus (ARCA) CN706: a selective cytotoxic for prostate-specific antigen-positive prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2559–2563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu DC, Chen Y, Seng M, et al. The addition of adenovirus type 5 region E3 enables calydon virus 787 to eliminate distant prostate tumor xenografts. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4200–4203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DeWeese TL, van der Poel H, Li S, et al. A phase I trial of CV706, a replication-competent, PSA selective oncolytic adenovirus, for the treatment of locally recurrent prostate cancer following radiation therapy. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7464–7472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li S, Simons J, Detorie N, et al. Dosimetric and technical considerations for interstitial adenoviral gene therapy as applied to prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;55:204–214. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)03862-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Assessment of adenoviral vector safety and toxicity: report of the National Institutes of Health Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee. Hum Gene Ther. 2002;13:3–13. doi: 10.1089/10430340152712629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lichtenstein DL, Wold WS. Experimental infections of humans with wild-type adenoviruses and with replication-competent adenovirus vectors: replication, safety, and transmission. Cancer Gene Ther. 2004;11:819–829. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu DC, Chen Y, Dilley J, et al. Antitumor synergy of CV787, a prostate cancer-specific adenovirus, and paclitaxel and docetaxel. Cancer Res. 2001;61:517–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodriguez R, Lim HY, Bartkowski LM, Simons JW. Identification of diphtheria toxin via screening as a potent cell cycle and p53-independent cytotoxin for human prostate cancer therapeutics. Prostate. 1998;34:259–269. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19980301)34:4<259::aid-pros3>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mesnil M, Piccoli C, Tiraby G, et al. Bystander killing of cancer cells by herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene is mediated by connexins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1831–1835. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Freeman SM, Abboud CN, Whartenby KA, et al. The “bystander effect”: tumor regression when a fraction of the tumor mass is genetically modified. Cancer Res. 1993;53:5274–5283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen SH, Shine HD, Goodman JC, et al. Gene therapy for brain tumors: regression of experimental gliomas by adenovirus-mediated gene transfer in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3054–3057. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Herman JR, Adler HL, Aguilar-Cordova E, et al. In situ gene therapy for adenocarcinoma of the prostate: a phase I clinical trial. Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10:1239–1249. doi: 10.1089/10430349950018229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shalev M, Kadmon D, Teh BS, et al. Suicide gene therapy toxicity after multiple and repeat injections in patients with localized prostate cancer. J Urol. 2000;163:1747–1750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miles BJ, Shalev M, Aguilar-Cordova E, et al. Prostate-specific antigen response and systemic T cell activation after in situ gene therapy in prostate cancer patients failing radiotherapy. Hum Gene Ther. 2001;12:1955–1967. doi: 10.1089/104303401753204535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Freytag SO, Rogulski KR, Paielli DL, et al. A novel three-pronged approach to kill cancer cells selectively: concomitant viral, double suicide gene, and radiotherapy. Hum Gene Ther. 1998;9:1323–1333. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.9-1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bischoff JR, Kirn DH, Williams A, et al. An adenovirus mutant that replicates selectively in p53-deficient human tumor cells. Science. 1996;274:373–376. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5286.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O’Shea CC, Johnson L, Bagus B, et al. Late viral RNA export, rather than p53 inactivation, determines ONYX-015 tumor selectivity. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:611–623. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Freytag SO, Khil M, Stricker H, et al. Phase I study of replication-competent adenovirus-mediated double suicide gene therapy for the treatment of locally recurrent prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4968–4976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Collis SJ, DeWeese TL, Jeggo PA, Parker AR. The life and death of DNA-PK. Oncogene. 2005;24:949–961. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boyer J, Rohleder K, Ketner G. Adenovirus E4 34k and E4 11k inhibit double strand break repair and are physically associated with the cellular DNA-dependent protein kinase. Virology. 1999;263:307–312. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stracker TH, Carson CT, Weitzman MD. Adenovirus oncoproteins inactivate the Mre11-Rad50-NBS1 DNA repair complex. Nature. 2002;418:348–352. doi: 10.1038/nature00863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taccioli GE, Amatucci AG, Beamish HJ, et al. Targeted disruption of the catalytic subunit of the DNA-PK gene in mice confers severe combined immunodeficiency and radiosensitivity. Immunity. 1998;9:355–366. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80618-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chernikova SB, Wells RL, Elkind MM. Wortmannin sensitizes mammalian cells to radiation by inhibiting the DNA-dependent protein kinase-mediated rejoining of double-strand breaks. Radiat Res. 1999;151:159–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen Y, DeWeese T, Dilley J, et al. CV706, a prostate cancer-specific adenovirus variant, in combination with radiotherapy produces syner-gistic antitumor efficacy without increasing toxicity. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5453–5460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smalley SR, Kimler BF, Evans RG. 5-Fluorouracil modulation of radiosensitivity in cultured human carcinoma cells. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;20:207–211. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90091-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chhikara M, Huang H, Vlachaki MT, et al. Enhanced therapeutic effect of HSV-tk+GCV gene therapy and ionizing radiation for prostate cancer. Mol Ther. 2001;3:536–542. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2001.0298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rogulski KR, Wing MS, Paielli DL, et al. Double suicide gene therapy augments the antitumor activity of a replication-competent lytic adenovirus through enhanced cytotoxicity and radiosensitization. Hum Gene Ther. 2000;11:67–76. doi: 10.1089/10430340050016166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zeng M, Cerniglia GJ, Eck SL, Stevens CW. High-efficiency stable gene transfer of adenovirus into mammalian cells using ionizing radiation. Hum Gene Ther. 1997;8:1025–1032. doi: 10.1089/hum.1997.8.9-1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reid T, Warren R, Kirn D. Intravascular adenoviral agents in cancer patients: lessons from clinical trials. Cancer Gene Ther. 2002;9:979–986. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wilding G, Carducci M, Yu D, et al. A Phase I/II trial of IV CG7870, a replication-selective, PSA-targeted oncolytic adenovirus (OAV), for the treatment of hormone-refractory, metastatic prostate cancer [abstract] J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3036. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wickham TJ. Ligand-directed targeting of genes to the site of disease. Nat Med. 2003;9:135–139. doi: 10.1038/nm0103-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Glasgow JN, Bauerschmitz GJ, Curiel DT, Hemminki A. Transductional and transcriptional targeting of adenovirus for clinical applications. Curr Gene Ther. 2004;4:1–14. doi: 10.2174/1566523044577997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Everts M, Curiel DT. Transductional targeting of adenoviral cancer gene therapy. Curr Gene Ther. 2004;4:337–346. doi: 10.2174/1566523043346372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Douglas JT, Rogers BE, Rosenfeld ME, et al. Targeted gene delivery by tropism-modified adenoviral vectors. Nat Biotechnol. 1996;14:1574–1578. doi: 10.1038/nbt1196-1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wickham TJ, Roelvink PW, Brough DE, Kovesdi I. Adenovirus targeted to heparan-containing receptors increases its gene delivery efficiency to multiple cell types. Nat Biotechnol. 1996;14:1570–1573. doi: 10.1038/nbt1196-1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Krasnykh V, Dmitriev I, Mikheeva G, et al. Characterization of an adenovirus vector containing a heterologous peptide epitope in the HI loop of the fiber knob. J Virol. 1998;72:1844–1852. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.1844-1852.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Santis G, Legrand V, Hong SS, et al. Molecular determinants of adenovirus serotype 5 fibre binding to its cellular receptor CAR. J Gen Virol. 1999;80(pt 6):1519–1527. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-6-1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roelvink PW, Mi Lee, Einfeld DA, et al. Identification of a conserved receptor-binding site on the fiber proteins of CAR-recognizing adenoviridae. Science. 1999;286:1568–1571. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5444.1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kirby I, Davison E, Beavil AJ, et al. Mutations in the DG loop of adenovirus type 5 fiber knob protein abolish high-affinity binding to its cellular receptor CAR. J Virol. 1999;73:9508–9514. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.11.9508-9514.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kirby I, Davison E, Beavil AJ, et al. Identification of contact residues and definition of the CAR-binding site of adenovirus type 5 fiber protein. J Virol. 2000;74:2804–2813. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.6.2804-2813.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jakubczak JL, Rollence ML, Stewart DA, et al. Adenovirus type 5 viral particles pseudotyped with mutagenized fiber proteins show diminished infectivity of coxsackie B-adenovirus receptor-bearing cells. J Virol. 2001;75:2972–2981. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.6.2972-2981.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Smith TA, Idamakanti N, Marshall-Neff J, et al. Receptor interactions involved in adenoviral-mediated gene delivery after systemic administration in non-human primates. Hum Gene Ther. 2003;14:1595–1604. doi: 10.1089/104303403322542248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Martin K, Brie A, Saulnier P, et al. Simultaneous CAR- and alpha V integrin-binding ablation fails to reduce Ad5 liver tropism. Mol Ther. 2003;8:485–494. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(03)00182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Koizumi N, Mizuguchi H, Sakurai F, et al. Reduction of natural adenovirus tropism to mouse liver by fiber-shaft exchange in combination with both CAR- and alphav integrin-binding ablation. J Virol. 2003;77:13062–13072. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.24.13062-13072.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Einfeld DA, Schroeder R, Roelvink PW, et al. Reducing the native tropism of adenovirus vectors requires removal of both CAR and integrin interactions. J Virol. 2001;75:11284–11291. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.23.11284-11291.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Akiyama M, Thorne S, Kirn D, et al. Ablating CAR and integrin binding in adenovirus vectors reduces nontarget organ transduction and permits sustained bloodstream persistence following intraperitoneal administration. Mol Ther. 2004;9:218–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lupold SE, Rodriguez R. Disulfide-constrained peptides that bind to the extracellular portion of the prostate-specific membrane antigen. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:597–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xia D, Henry L, Gerard RD, Deisenhofer J. Tags for format 3Structure of the receptor binding domain of adenovirus type 5 fiber protein. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;199(pt 1):39–46. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-79496-4_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chen J, Anderson JB, DeWeese-Scott C, et al. MMDB: Entrez’s 3D-structure database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:474–477. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]