Abstract

Cellular infection by cytomegalovirus (CMV) is associated with very early G-protein-mediated signal transduction and reprogramming of gene expression. Here we investigated the involvement of human CMV (HCMV)-encoded US27, US28, and UL33 receptors as well as murine CMV-encoded M33 transmembrane (7TM) receptors in host cell signaling mechanisms. HCMV-encoded US27 did not show any constitutive activity in any of the studied signaling pathways; in contrast, US28 and M33 displayed ligand-independent, constitutive signaling through the G protein q (Gq)/phospholipase C pathway. In addition, M33 and US28 also activated the transcription factor NF-κB as well as the cyclic AMP response element binding protein (CREB) in a ligand-independent, constitutive manner. The use of specific inhibitors indicated that the p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase but not the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2-MAP kinase pathway is involved in M33- and US28-mediated CREB activation but not NF-κB activation. Interestingly, UL33—the HCMV-encoded structural homologue of M33—was only marginally constitutively active in the Gq/phospholipase C turnover and CREB activation assays and did not show any constitutive activity in the NF-κB pathway, where M33 and US28 were highly active. Hence, CMVs appear to have conserved mechanisms for regulating host gene transcription, i.e., constitutive activation of certain kinases and transcription factors through the constitutive activities of 7TM proteins. These data, together with the previous identification of the incorporation of such proteins in the viral envelope, suggest that these proteins could be involved in the very early reprogramming of the host cell during viral infection.

Cytomegaloviruses (CMVs) are widespread opportunistic pathogens that cause acute, latent, and chronic infections. Although the primary infection is asymptomatic in immunocompetent individuals, these viruses can cause a wide variety of diseases in immunocompromised hosts (2). One hallmark of human CMV (HCMV) infection of quiescent cells is the upregulation of many host cell proteins, including DNA replication enzymes and transcription factors, which are necessary for both viral gene expression and viral DNA replication. Interestingly, some of these cellular changes occur even before the activation of the immediate-early genes of the virus, and some of these changes are clearly associated with classical G-protein signaling pathways. For example, the exposure of human fibroblasts to HCMV is associated with a very rapid G-protein-dependent increase in phospholipase C (PLC) activity, as reflected in the intracellular levels of diacylglycerol and inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate, as well as the rapid release of arachidonic acid metabolites (1).

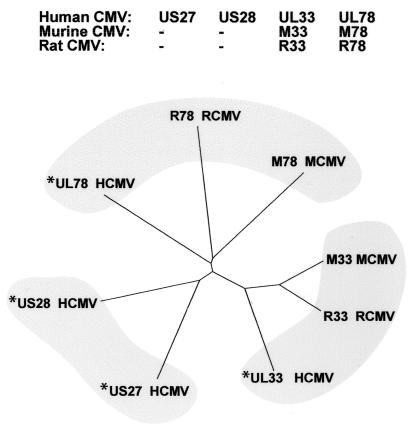

HCMV encodes four putative 7-transmembrane (7TM) G-protein-coupled receptors, US27 and US28 (both HCMV specific) and UL33 and UL78 (both betaherpesvirus conserved) (11, 20, 31) (Fig. 1), with structural homology to chemokine receptors. So far, only US28 has been characterized pharmacologically and shown to bind several CC chemokines, such as MIP-1α/CCL3, MCP-1/CCL2, MIP-1β/CCL4, and RANTES/CCL5 (31), as well as the CX3C chemokine fractalkine/CX3CL1, with a high affinity (26). Of these, RANTES/CCL5 and MCP-1/CCL2 were able to mediate the migration of smooth muscle cells following CMV infection, suggesting that US28 is one of the possible causative agents in the pathogenesis of artherosclerosis and restenosis (39). While mostly intracellular, US28 has also been suggested to enhance cell-cell fusion, demonstrating its potential importance in the cell-to-cell spread of HCMV in vivo (23, 26). The betaherpesvirus family members UL33 and UL78 (Fig. 1) have been less well characterized; while ligand(s) for UL33 have not yet been identified, the critical importance of the rodent CMV counterparts, M33 and R33 (Fig. 1, right bottom cluster), has been demonstrated through in vivo analysis of gene-knockout viruses. Viruses with M33 and R33 deleted were less virulent and were unable to disseminate to or replicate within the salivary glands. The salivary glands are the major site for CMV persistence and transmission; thus, M33 and R33 appear to play critical roles in this aspect of the virus life cycle (5, 13). For both animal viruses, only one more putative 7TM product has been described, M78 (32) and R78 (4), respectively (Fig. 1, top cluster).

FIG. 1.

Dendrogram of CMV-encoded chemokine receptors based on their amino acid identities. This phylogenetic tree was generated by Francois Talabot, Serono Pharmacological Research Institute, by using Clustal W 1.5 alignments of the full amino acid sequences followed by analysis with the Distance program (Genetics Computer Group, Madison, Wis.). The length of each branch reflects the identity between the receptors. Tree View (http://taxonomy.zoology.gla.ac.uk/rod/rod.html) was used for graphic presentation. Asterisks indicate members of the human CMV receptor family.

Initial studies on the signal transduction properties of US28 revealed that this receptor accounts for calcium mobilization in response to high CC chemokine concentrations in HCMV-infected cells (41) as well as for RANTES/CCL5-mediated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)-mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase activation in specialized cellular environments (6). Recently, US28 was shown to regulate the G protein q (Gq)/PLC pathway in a ligand-independent, constitutively active manner and to upregulate the transcription factor NF-κB (10).

Here we studied the constitutive activation of the Gq/PLC/inositol pathway and the upregulation of transcription factors by the murine CMV (MCMV) M33 and HCMV US27, US28, and UL33 chemokine receptor-like proteins. Moreover, we extended the search for potential downstream effectors of these viral 7TM proteins and found that the cyclic AMP (cAMP) response element binding protein (CREB) is constitutively upregulated via some of these proteins. Since both NF-κB and CREB are regulated by the concerted action of various host cell kinases—many of which are known to be upregulated in early CMV infectious processes—we investigated the potential involvement of p38 MAP kinase and ERK1/2-MAP kinase in regulating the respective transcription factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemokines and receptor constructs.

CX3CL1 (i.e., the chemokine domain corresponding to amino acids 1 through 69 of fractalkine) and RANTES/CCL5 were purchased from R&D Systems. MCP-3/CCL7 and MIP-1β/CCL4 were purchased from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, N.J.). MIP-1α/CCL3, MCP-1/CCL2, vMIP-II/vCCL2, and the cDNA encoding the US28 chemokine receptor (AD169 strain of HCMV) were kindly provided by Timothy N. C.Wells (Serono Pharmacological Research Institute, Geneva, Switzerland). M33 (long-splice variant) was cloned from mouse embryonic fibroblasts infected with the K181 strain of MCMV, UL33 (long-splice variant) was cloned from a human foreskin fibroblast culture infected with the AD169 strain of HCMV (13), and US27 was cloned from fibroblast cultures infected with the AD169 strain of HCMV (kindly provided by Allan Hornsleth, University of Copenhagen) by using PCR. For microscopy studies, US28, UL33, and M33 were fused upstream of and in frame with enhanced green fluorescence protein (EGFP), and US27 was tagged with yellow fluorescence protein (YFP). All constructs were cloned in the eukaryotic expression vector pTEJ8 (24) and verified by DNA sequencing. Pertussis toxin (PTX) was purchased from Sigma. PD98059 and SB202190 were obtained from Calbiochem.

Transfections and cells.

COS-7 cells were grown with 10% CO2 at 37°C in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium 1885 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM glutamine, and 100 U of penicillin G-streptomycin/ml. Cells were transiently transfected with cDNA by using the calcium phosphate precipitation method (12) or with Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies)

Phosphatidylinositol assay.

COS-7 cells were transferred to 12-well culture plates 1 day after transfection. Cells (2.5 × 105 cells/well) were incubated for 24 h with 5μCi of myo-[3H]inositol in 0.5 ml of complete medium/well. Cells were washed twice in 20 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) supplemented with 140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 1 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose, and 0.05% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin and were incubated in 0.5 ml of buffer supplemented with 10 mM LiCl at 37°C for 45 min in the presence of various concentrations of chemokines. Cells were extracted by the addition of 0.5 ml of 10% ice-cold perchloric acid; this step was followed by incubation on ice for 30 min. The cell extracts were neutralized with KOH in HEPES buffer, and the generated [3H]inositol phosphates were purified on AG 1X8 anion-exchange resin.

Reporter gene assays.

COS-7 cells (35,000 cells/well) seeded in 96-well plates were transiently transfected with a reporter-cDNA cocktail consisting of pFA2-CREB and pFR-Luc reporter plasmids (PathDetect CREB trans-Reporting system; Stratagene) or pNF-κB-Luc (PathDetect cis-Reporting system; Stratagene) and various amounts of receptor DNA. Following transfection, cells were treated with the respective compounds in an assay volume of 100 μl for 24 h. When treated with chemokines, cells were maintained with a low serum concentration (2.5%) throughout the experiments. The assay was terminated by washing the cells twice with phosphate-buffered saline and adding 100 μl of luciferase assay reagent (LucLite; Packard). Luminescence was measured in a TopCounter (Top Count NXT; Packard) for 5 s. Luminescence values are given as relative light units (RLU).

Fluorescence microscopy.

COS-7 cells expressing the green fluorescence protein (GFP)-labeled receptor constructs 2 days after transfection were used for fluorescence microscopy. At 24 h posttransfection, cells were plated on coverslips and allowed to grow for 24 h. Subsequently, cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline for 20 min at room temperature and mounted in Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories). Cells were analyzed by using an inverse Zeiss Axiovert 200 fluorescence microscope equipped with a Coolsnap charge-coupled device camera. Digital images were transferred to Adobe Photoshop and used without further processing.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Effect of receptor expression on phosphatidylinositol turnover.

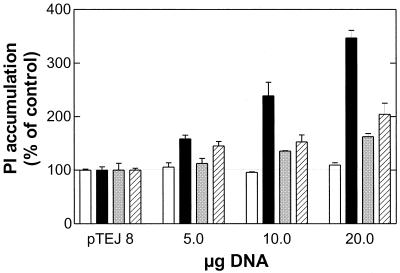

A classical way of studying constitutive signaling of receptors is to perform gene dose experiments, where cells are transfected with increasing amounts of a plasmid coding for the receptor and the relevant second messenger is measured in the cells in the absence of an added receptor ligand (3, 34). Figure 2 shows that of the four tested CMV proteins expressed in COS-7 cells, only US28 induced a clear increase in phosphatidylinositol turnover in a gene-dose-dependent manner above the control. M33 and UL33 each showed a marginal degree of constitutive activity, whereas US27 did not display any constitutive activity above the baseline (pTEJ8). This lack of signaling cannot be accounted for by a failure of receptor expression, as this was verified by fluorescence detection of GFP-tagged receptors (see below).

FIG. 2.

Inositol phosphate (PI) accumulation induced by US27, US28, UL33, and M33 receptor activities. Gene dose experiments with increasing concentrations of US27 (white bar), US28 (black bar), UL33 (grey bar), and M33 (hatched bar) receptor DNAs were performed with transiently transfected COS-7 cells. One hundred percent corresponds to the basal activity of cells transfected with 20 μg of the empty expression vector pTEJ8. Data are means and standard errors of the means for three experiments carried out in quadruplicate.

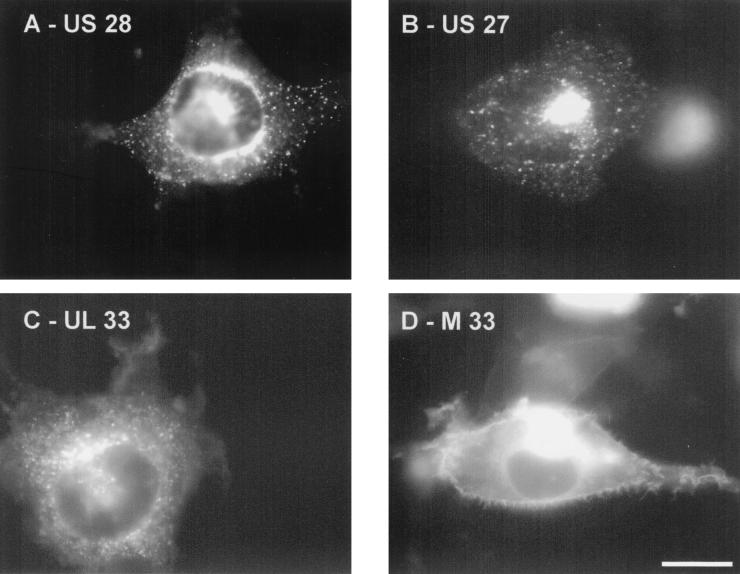

Cellular localization.

It was previously demonstrated that although US28 is expressed at the cell surface, it is constitutively internalized, and the majority of these receptors accumulate in late endosomes in the perinuclear region of the cell (16). Figure 3 shows that US27-YFP is located in a pattern rather similar to that of US28-EGFP (Fig. 3A and B), i.e., mostly in intracellular and perinuclear compartments. Although UL33-EGFP is expressed slightly more on the cell surface than US27 and US28, the majority of the protein is still found inside the cell (Fig. 3C). In contrast, M33-EGFP is located primarily on the cell surface, although a fraction is seen within cells in the perinuclear region (Fig. 3D). HCMV virions have been proposed to obtain their outer membrane from endosomal compartments (40), and both UL33 and US27 have been shown to be part of the viral envelope (29). By immunolabeling cryosections of HCMV-infected cells, it was recently demonstrated that both US27 and UL33 are located in the membranes of multivesicular endosomes and small membrane vesicles, and HCMV virions could be seen budding into these membranes (17). Since US27, US28, UL33, and potentially M33 may be incorporated into virions and thereby delivered to new cells during infection, these proteins may be involved in the very rapid reprogramming of newly infected cells.

FIG. 3.

Cellular localization of US28, US27, UL33, and M33 in COS-7 cells. COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with US28-EGFP (A), US27-YFP (B), UL33-EGFP (C), or M33-EGFP (D). US28-EGFP (A) and US27-YFP (B) were mostly located on intracellular vesicles in the perinuclear regions of the cells. UL33-EGFP (C) was distributed both intracellulary and on the cell surface. M33-EGFP (D) was found predominantly on the cell membrane surface. Shown are representative fluorescence microscopy images of the distribution of the GFP- and YFP-tagged receptors taken with a ×100 oil immersion objective. Bar, 10 μm

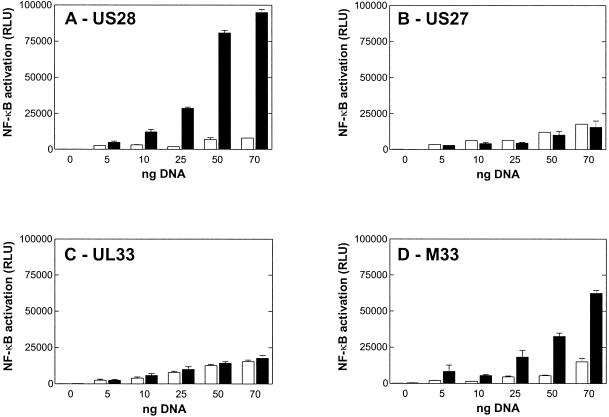

Activation of the nuclear transcription factor NF-κB.

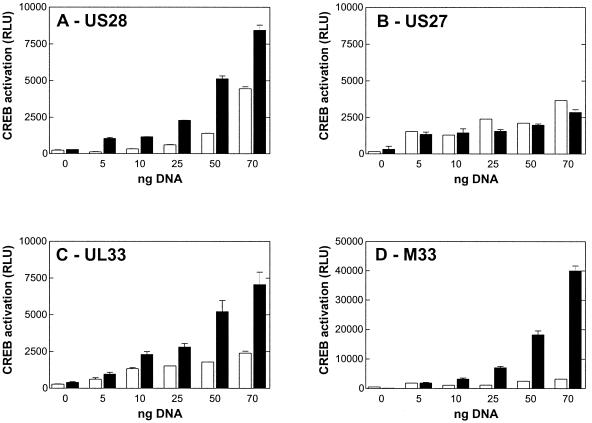

Several immediate-early and early viral promoters contain DNA binding sites for a number of cellular transcription factors of the host (30). These include CREB, NF-κB, serum response factor, and numerous cellular proto-oncogenes, such as c-myc, c-jun, and c-fos, have been shown to be induced after HCMV infection (8, 15, 42). This activation ensures high levels of expression of many viral and cellular genes, which are required for completion of the lytic viral life cycle. HCMV activates NF-κB-mediated transcription very rapidly after cellular infection, and one of the major targets that is transactivated by NF-κB is the major immediate-early gene promoter of HCMV itself. Although it has long been proposed that NF-κB activation by HCMV occurs through a G-protein-mediated mechanism (9, 37, 38), to date only US28 out of the four HCMV-encoded 7TM receptors has been described to constitutively activate NF-κB (Fig. 4A) (10). Here, we tested whether US27, UL33, and its murine homologue M33 also could activate NF-κB. As shown in Fig. 4D, M33 was highly constitutively active in the induction of NF-κB. In contrast, neither UL33 (Fig. 4C) nor US27 (Fig. 4B) showed a significant gene-dose-dependent activation of NF-κB above that of the control transfected cells.

FIG. 4.

Gene-dose-dependent induction of NF-κB activity by US28, US27, UL33, and M33. Induction of NF-κB-luciferase was determined in transiently transfected COS-7 cells (35,000 cells/well). Cells were cotransfected with 50 ng of NF-κB-luciferase vector together with increasing amounts of either pTEJ8 vector DNA (white bars) as a control or US28 (A), US27 (B), UL33 (C), or M33 (D) DNA (black bars). Shown are representative results from at least four independent experiments performed in quadruplicate. Data are means and standard errors of the means. RLU were measured with a Packard TopCounter (5 s/well).

Activation of the transcription factor CREB.

CREB activates the transcription of target genes in response to a diverse array of stimuli, including peptide hormones, growth factors, and neuronal activity, that activate not only protein kinase A (PKA) but also a variety of other kinases, such as MAP kinases and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases (for a review, see reference 36). For HCMV, sustained MAP kinase activity has been shown to be a major event in the very early infection process, resulting in CREB-mediated induction of immediate-early genes (33). While US27 (Fig. 5B) could not raise CREB activity above the baseline, US28 (Fig. 5A) was able to activate the CREB reporter in a ligand-independent manner. Interestingly, in this experiment, UL33 (Fig. 5C) was capable of constitutively regulating CREB-luciferase to a degree similar to that seen with US28. The murine homologue of UL33, M33, showed strong constitutive activation of CREB-luciferase (Fig. 5D).

FIG. 5.

Induction of CREB activity by US28, US27, UL33, and M33. Activation of CREB-luciferase was determined in transiently transfected COS-7 cells (35,000 cells/well). Cells were cotransfected with a CREB-luciferase vector mixture (for details, see Materials and Methods) together with increasing amounts of either vector DNA (white bars) as a control or US28 (A), US27 (B), UL33 (C), or M33 (D) DNA (black bars). Shown are representative results from at least four independent experiments performed in quadruplicate. Data are means and standard errors of the means. RLU were measured with a Packard TopCounter (5 s/well).

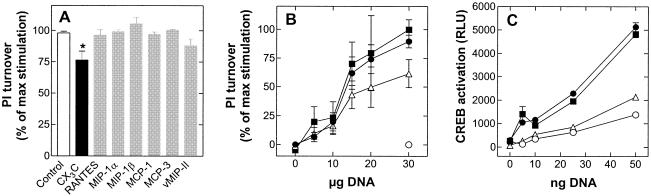

Effect of chemokines on the constitutive activity of US28.

A direct demonstration of the degree of constitutive receptor signaling in a given cellular setting requires the use of a suitable inverse agonist as a pharmacological tool, as previously shown for the ORF-74 receptor from human herpesvirus 8 (34). However, US27, UL33, and M33 have not yet been “de-orphanized” in terms of identification of their endogenous ligands; thus, the following experiments were limited to US28, which is known to be a broad-spectrum receptor for CC chemokines (18, 26, 27, 31). However, none of the CC chemokine ligands tested (RANTES/CCL5, MIP-1α/CCL3, MIP-1β/CCL4, MCP-1/CCL2, MCP-3/CCL7, and vMIP-II/vCCL2) affected US28-mediated constitutive inositol phosphate turnover (Fig. 6A) or NF-κB or CREB transcription (data not shown). As previously demonstrated, US28 was optimized to specifically recognize the membrane-associated CX3C chemokine, fractalkine/CX3CL1, with a high affinity (26). The chemokine domain of fractalkine/CX3CL1 (100 nM) acted as a partial inverse agonist for US28, as it decreased signaling to approximately 70% for inositol phosphate turnover (Fig. 6A and B). An even more profound effect of fractalkine/CX3CL1 was observed for US28-mediated CREB activation (Fig. 6C), whereas RANTES/CCL5 or any of the other above-mentioned chemokines had no effect on constitutive CREB activation by US28 (Fig. 6B and C). The same chemokine profile was previously reported for NF-κB activation by US28 (10). In addition, no ligand-induced inositol phosphate turnover could be observed when COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with US27 (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

Modulation of US28-induced inositol phosphate (PI) turnover and CREB activity by various CC chemokines and CX3CL. (A) Effects of a 100 nM concentration of the chemokine domain of fractalkine/CX3CL1 (black bar) and RANTES/CCL5, MIP-1α/CCL3, MIP-1β/CCL4, MCP-1/CCL2, MCP-3/CCL7, and vMIP-II/vCCL2 (grey bars) on the basal inositol phosphate turnover in COS-7 cells transfected with US28. The asterisk indicates a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05; unpaired t test) from the maximally obtained basal activity (control, white bar). Experiments were carried out in duplicate (n = 5). (B) Effect of RANTES/CCL5 (filled squares) or the chemokine domain of fractalkine/CX3CL (open triangles) on the basal inositol phosphate turnover (filled circles) in COS-7 cells transiently transfected with the indicated amounts of US28 receptor DNA. The basal activity of 30 μg of US27 is indicated by an open circle. One hundred percent corresponds to the maximally obtained basal activity, and 0% corresponds to the background activity obtained with 30 μg of empty expression vector pTEJ8. (C) COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with increasing amounts of US28 receptor DNA and 50 ng of CREB-luciferase cDNA. The cells were exposed to either 100 nM RANTES/CCL5 (filled squares) or 100 nM fractalkine/CX3CL1 (open triangles) immediately following transfection. Basal constitutive activity of US28 is represented by filled circles, and the activity in mock-transfected cells is represented by open circles. Shown are representative results from at least four independent experiments performed in quadruplicate. Data in all three panels are means and standard errors of the means.

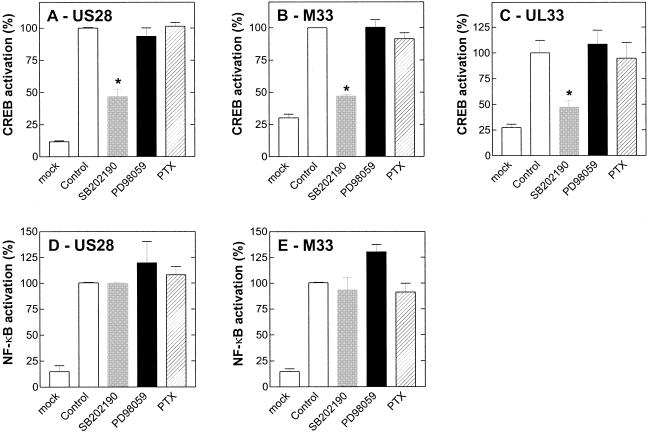

p38 MAP kinase but not ERK1/2-MAP kinase is partially involved in US28-, UL33-, and M33-mediated CREB activation.

Since the transactivation function of many cellular transcription factors is at least partially regulated by phosphorylation events, identifying and inhibiting cellular kinases which phosphorylate transcription factors may represent one mechanism for inhibiting HCMV infection and/or replication. MAP kinases are examples of kinases which activate numerous transcription factors, and some members of the MAP kinase family are strongly activated following HCMV infection (33). In mammalian cells, three general groups of MAP kinases have been identified: ERK1/2, c-Jun N-terminal kinase, and p38 (for a review, see reference 22). HCMV infection has been found to activate both ERK1/2 and p38. ERK1/2 activation is observed 5 to 15 min following viral binding to the cell and at 4 to 8 h postinfection following viral gene expression (33), whereas increased p38 activity is detected at 8 h and maintained through 48 h postinfection (25). Hence, we next investigated the involvement of the two main upstream MAP kinases involved in CREB transcription via US28, UL33, and M33, i.e., ERK1/2 and p38 MAP kinases (36). The application of a 1 μM concentration of the selective p38 inhibitor SB202190 decreased CREB activation by US28 (Fig. 7A), M33 (Fig. 7B), and UL33 (Fig. 7C). This effect was specific, since 1 μM SB202190 did not impair the activation of NF-κB by US28 (Fig. 7D) and M33 (Fig. 7E). Concentrations higher than 1 μM SB202190 resulted in nonspecific effects on both CREB and NF-κB reporter plasmids alone (data not shown).We also showed that ERK1/2 is not involved in the CREB activation process, since up to 30 μM PD98059 had no effect on signaling by either US28 (Fig. 7A), M33 (Fig. 7B),or UL33 (Fig. 7C).

FIG. 7.

Effects of selected MAP kinase inhibitors and the Gαi inhibitor PTX on receptor-mediated constitutive activation of CREB and NF-κB. COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with 40 ng of US28 (A and D), M33 (B and E), or UL33 (C) receptor DNA and 50 ng of either CREB-luciferase (A, B, and C) or NF-κB-luciferase (D and E) reporter DNA. Immediately following transfection, cells were incubated with a 1 μM concentration of the selective p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB202190 (grey bars) or a 30 μM concentration of the ERK1/2-MAP kinase inhibitor PD98059 (black bars). Likewise, transiently transfected COS-7 cells were treated with PTX (100 ng/ml) for 24 h (hatched bars). Data are shown as percentages of the data for the control (100%), whereby the control represents the maximal constitutive activation of the respective reporter in the presence of 40 ng of the respective receptor. The asterisk indicates a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05; unpaired t test) from the maximally obtained basal activity (control, white bar). Data are means and standard errors of the means for at least four independent experiments performed in quadruplicate.

Since we could not totally eliminate the constitutive activation of CREB via p38 MAP kinase, we tested whether the Gαi-cAMP-PKA pathway could account for this residual effect on CREB transcription. However, the application of 100 ng of the selective Gαi inhibitor PTX/ml did not affect CREB reporter activation by US28 (Fig. 7A), M33 (Fig. 7B), or UL33 (Fig. 7C). To date, the only report that Gαi is involved in intracellular signaling mediated by US28 is ligand-induced Ca2+ mobilization (6, 36, 41); however, neither ligand-mediated smooth muscle cell migration (39) nor constitutive activation of NF-κB (Fig. 7D) (10) was inhibited by PTX treatment.

CMV-encoded receptors regulate NF-κB transcription via ERK1/2- and p38 MAP kinase-insensitive pathways.

It is known that NF-κB activation can be regulated by multiple pathways, including MAP kinases and inhibition of cAMP-PKA (6, 14). However, our data suggest that the p38 MAP kinase, ERK1/2-MAP kinase, and Gαi-cAMP-PKA pathways are not involved in US28 (Fig. 7D)- or M33 (Fig. 7E)-mediated NF-κB transcription, since none of the inhibitors used affected the constitutive activation of NF-κB. The slightly elevating effect of 30 μM PD98059 on NF-κB-luciferase activity (Fig. 7D and E) likely was a nonspecific effect, since it was observed even in mock-transfected cells (data not shown)

In the present study, we have identified and characterized constitutive activity of the MCMV-encoded M33 receptor and compared its signaling profiles to those of the HCMV-encoded US28, US27, and UL33 (structural homologue of M33) receptors. Our data suggest that constitutive activation of the host cell transcription factors NF-κB (Fig. 4) and CREB (Fig. 5) is a more common feature in CMV-encoded 7TM receptors than previously assumed. However, the levels of transcriptional activation differ quite remarkably between the receptors. We found that not only US28 but also UL33 and M33, besides activating the PLC pathway in a ligand-independent manner (Fig. 2), also upregulated the transcription factor CREB (Fig. 5). Our data further suggest that the primary route for this constitutive CREB activation is through the p38 MAP kinase pathway (Fig. 7). Interestingly, constitutive activation of transcription factor NF-κB was observed with only US28 from HCMV and M33 from MCMV (Fig. 4A and D) and not with the HCMV homologue of M33, UL33 (Fig. 4C). UL33 was able to constitutively activate the Gq/PLC pathway (Fig. 2), although apparently at a level insufficient for downstream NF-κB upregulation. A very recent study showed that R33, the RCMV homologue of M33, like M33, is able to constitutively activate NF-κB transcription in a G-protein-dependent manner (21). A possible structural explanation for the lack of NF-κB upregulation via UL33 could be that both M33 and R33—but not UL33—possess an Asn (N) instead of an Asp (D) in the otherwise well-conserved DRY motif located at the boundary of transmembrane helix 3 and the second intracellular loop of almost all G-protein-coupled receptors. This conserved Asp-Arg-Tyr motif plays a pivotal role in G-protein activation of 7TM receptors (35), and substitution of Asp with Asn, as in M33 and R33, usually results in increased constitutive activity (19, 28).

HCMV encodes two “extra” 7TM receptors, US27 and US28, which are not found in the rodent CMVs (Fig. 1). It could be argued either that US27 and US28 have been gained by the human virus or that the two receptors have been lost by the rodent virus. Whatever the case, it is interesting that, with respect to signaling properties, M33 is more similar to US28 than to UL33, as both receptors are highly constitutively active in the Gq/PLC signaling pathway, in CREB transcription, and especially in NF-κB transcription. Thus, it is likely that M33 plays a role similar to that of US28 at least in certain parts of the viral life circle. However, US28 also has been suggested to be involved in the sequestration of chemokines from the environment of infected cells (7) and in cell-to-cell transfer of virus (23, 26), based on the fact that US28 binds a broad variety of CC chemokines besides the CX3C chemokine fractalkine/CX3CL1. Such functions cannot at present be associated with M33, as no chemokine ligands have yet been identified for this receptor. Nevertheless, it should be noted that both M33 and R33 have been shown to be essential in vivo for targeting of CMV to or replication of CMV in the salivary glands of the host (5, 13).

Acknowledgments

We thank Mark Marsh and Alberto Fraile-Ramos for critically reading the manuscript. We thank Michala Tved for excellent technical assistance and Francois Talabot for generating the phylogenetic tree.

This study was supported by an EMBO fellowship (ALTF 717-1999) granted to M.W. and by grants from the Danish Medical Research Council to T.W.S.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abubakar, S., I. Boldogh, and T. Albrecht. 1990. Human cytomegalovirus stimulates arachidonic acid metabolism through pathways that are affected by inhibitors of phospholiphase A2 and protein kinase C. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 166:953-959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alford, C. A., and W. J. Britt. 1995. Cytomegaloviruses, p. 2493-2534. In B. N. Fields, D. M. Knipe, and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology. Lippincott-Raven Publishers, New York, N.Y.

- 3.Ambinder, R. F., K. D. Robertson, and Q. Tao. 1999. DNA methylation and the Epstein-Barr virus. Semin. Cancer Biol. 9:369-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beisser, P. S., G. Grauls, C. A. Bruggeman, and C. Vink. 1999. Deletion of the R78 G protein-coupled receptor gene from rat cytomegalovirus results in an attenuated, syncytium-inducing mutant strain. J. Virol. 73:7218-7230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beisser, P. S., C. Vink, J. G. Van Dam, G. Grauls, S. J. Vanherle, and C. A. Bruggeman. 1998. The R33 G protein-coupled receptor gene of rat cytomegalovirus plays an essential role in the pathogenesis of viral infection. J. Virol. 72:2352-2363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Billstrom, M. A., G. L. Johnson, N. J. Avdi, and G. Scott Worthen. 1998. Intracellular signalling by the chemokine receptor US28 during human cytomegalovirus infection. J. Virol. 72:5535-5544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Billstrom, M. A., L. A. Lehman, and G. Scott Worthen. 1999. Depletion of extracellular RANTES during human cytomegalovirus infection of endothelial cells. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 21:163-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boldogh, I., S. Abubakar, C. Z. Deng, and T. Albrecht. 1991. Transcriptional activation of cellular oncogenes fos, jun, and myc by human cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 65:1568-1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlquist, J. F., L. Edelman, D. W. Bennion, and J. L. Anderson. 1999. Cytomegalovirus induction of interleukin-6 in lung fibroblasts occurs independently of active infection and involves a G protein and the transcription factor, NF-κB. J. Infect. Dis. 179:1094-1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casarosa, P., R. A. Bakker, D. Verzijl, M. Navis, H. Timmerman, R. Leurs, and M. J. Smit. 2001. Constitutive signaling of the human cytomegalovirus-encoded chemokine receptor US28. J. Biol. Chem. 276:1133-1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chee, M. S., S. C. Satchwell, E. Preddie, K. M. Weston, and B. G. Barrell. 1990. Human cytomegalovirus encodes three G protein-coupled receptor homologues. Nature 344:774-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen, C. A., and H. Okayama. 1988. Calcium phosphate-mediated gene transfer: a highly efficient transfection system for stably transforming cells with plasmid DNA. BioTechniques 6:632-638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis-Poynter, N. J., D. M. Lynch, H. Vally, G. R. Shellam, W. D. Rawlinson, B. G. Barrell, and H. E. Farrell. 1997. Identification and characterization of a G protein-coupled receptor homolog encoded by murine cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 71:1521-1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delfino, F., and W. H. Walker. 1999. Hormonal regulation of the NF-κB signaling pathway. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 157:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dragic, T., V. Litwin, G. P. Allaway, S. R. Martin, Y. Huang, K. A. Nagashima, C. Cayanan, P. J. Maddon, R. A. Koup, J. P. Moore, and W. A. Paxton. 1996. HIV-1 entry into CD4+ cells in mediated by the chemokine receptor CC-CKR-5. Nature 381:667-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fraile-Ramos, A., T. N. Kledal, A. Pelchen-Matthews, K. Bowers, T. W. Schwartz, and M. Marsh. 2001. The human cytomegalovirus US28 protein is located in endocytic vesicles and undergoes constitutive endocytosis and recycling. Mol. Biol. Cell 12:1737-1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fraile-Ramos, A., A. Pelchen-Matthews, T. N. Kledal, H. Browne, T. W. Schwartz, and M. Marsh. 2002. Localization of human cytomegalovirus US27 and UL33 proteins in endocytic compartments and viral membranes. Traffic 3:218-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao, J. L., and P. M. Murphy. 1994. Human cytomegalovirus open reading frame US28 encodes a functional beta chemokine receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 269:28539-28542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gether, U. 2000. Uncovering molecular mechanisms involved in activation of G protein-coupled receptors. Endocrinol. Rev. 21:90-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gompels, U. A., J. Nicholas, G. Lawrence, M. Jones, B. J. Thomson, M. E. D. Martin, S. Efstathiou, M. Craxton, and H. A. Macaulay. 1995. The DNA sequence of human herpesvirus-6: structure, coding content, and genome evolution. Virology 209:29-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gruijthuijsen, Y. K., P. Casarosa, J. F. Kaptein, J. L. S. Broers, R. Leurs, C. A. Bruggeman, M. J. Smit, and C. Vink. 2002. The rat cytomegalovirus R33-encoded G protein-coupled receptor signals in a constitutive fashion. J. Virol. 76:1328-1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gutkind, J. S. 1998. Cell growth control by G protein-coupled receptors: from signal transduction to signal integration. Oncogene 17:1331-1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haskell, C. A., M. D. Cleary, and I. F. Charo. 2000. Unique role of the chemokine domain of fractalkine in cell capture: kinetics of receptor dissociation correlate with cell adhesion. J. Biol. Chem. 275:34183-34189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johansen, T. E., M. S. Schøller, S. Tolstoy, and T. W. Schwartz. 1990. Biosynthesis of peptide precursors and protease inhibitors using new constitutive and inducible eukaryotic expression vectors. FEBS Lett. 267:289-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson, R. A., S. M. Huong, and E. S. Huang. 2000. Activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase p38 by human cytomegalovirus infection through two distinct pathways: a novel mechanism for activation of p38. J. Virol. 74:1158-1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kledal, T. N., M. M. Rosenkilde, and T. W. Schwartz. 1998. Selective recognition of the membrane-bound CX3C chemokine, fractalkine, by the human cytomegalovirus-encoded broad-spectrum receptor US28. FEBS Lett. 441:209-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuhn, D. E., C. J. Beall, and P. E. Kolattukudy. 1995. The cytomegalovirus US28 protein binds multiple CC chemokines with high affinity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 211:325-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leurs, R., M. Hoffmann, A. E. Alewijnse, M. J. Smit, and H. Timmerman. 2002. Methods to determine the constitutive activity of histamine H2 receptors. Methods Enzymol. 343:405-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Margulies, B. J., H. Browne, and W. Gibson. 1996. Identification of the human cytomegalovirus G protein-coupled receptor homologue encoded by UL33 in infected cells and enveloped virus particles. Virology 225:111-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mocarski, E. S. 1995. Cytomegaloviruses and their replication, p. 2447-2492. In B. N. Fields, D. M. Knipe, and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology. Lippincott-Raven Publishers, New York, N.Y.

- 31.Neote, K., D. DiGregorio, J. Y. Mak, R. Horuk, and T. J. Schall. 1993. Molecular cloning, functional expression, and signalling characteristics of a C-C chemokine receptor. Cell 72:415-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oliveira, S. A., and T. E. Shenk. 2001. Murine cytomegalovirus M78 protein, a G protein-coupled receptor homologue, is a constituent of the virion and facilitates accumulation of immediate-early viral mRNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:3237-3242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodems, S. M., and D. H. Spector. 1998. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase activity is sustained early during human cytomegalovirus infection. J. Virol. 72:9173-9180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosenkilde, M. M., T. N. Kledal, H. Bräuner-Osborne, and T. W. Schwartz. 1999. Agonist and inverse agonist for the herpesvirus 8-encoded constitutively active seven-transmembrane oncogene product, ORF-74. J. Biol. Chem. 274:956-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwartz, T. W. 1996. Molecular structure of G-protein coupled receptors, p. 65-84. In J. C. Forman and T. Johansen (ed.), Textbook of receptor pharmacology. CRC Press, Inc., Boca Raton, Fla.

- 36.Shaywitz, A. J., and M. E. Greenberg. 1999. CREB: a stimulus-induced transcription factor activated by a diverse array of extracellular signals. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68:821-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shibutani, T., T. M. Johnson, Z.-X. Yu, V. J. Ferrans, J. Moss, and S. E. Epstein. 1997. Pertussis toxin-sensitive G proteins as mediators of the signal transduction pathways activated by cytomegalovirus infection of smooth muscle cells. J. Clin. Investig. 100:2054-2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Speir, E., T. Shibutani, Z.-X. Yu, V. J. Ferrans, and S. E. Epstein. 1996. Role of reactive oxygen intermediates in cytomegalovirus gene expression and in the response of human smooth muscle cells to viral infection. Circ. Res. 79:1143-1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Streblow, D. N., C. Soderberg-Naucler, J. Vieira, P. Smith, E. Wakabayashi, F. Ruchti, K. Mattison, Y. Altschuler, and J. A. Nelson. 1999. The human cytomegalovirus chemokine receptor US28 mediates vascular smooth muscle cell migration. Cell 99:511-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tooze, J., M. Hollinshead, B. Reis, K. Radsak, and H. Kern. 1993. Progeny vaccinia and human cytomegalovirus particles utilize early endosomal cisternae for their envelopes. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 60:163-178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vieira, J., T. J. Schall, L. Corey, and A. P. Geballe. 1998. Functional analysis of the human cytomegalovirus US28 gene by insertion mutagenesis with the green fluorescent protein gene. J. Virol. 72:8158-8165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yurochko, A. D., T. F. Kowalik, S. M. Huong, and E. S. Huang. 1995. Human cytomegalovirus upregulates NF-κB activity by transactivating the NF-κB p105/p50 and p65 promoters. J. Virol. 69:5391-5400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]