Abstract

To define the role of alpha/beta interferons (IFN-α/β) in simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection, IFN-α and IFN-β mRNA levels and mRNA levels of Mx, an antiviral effector molecule, were determined in lymphoid tissues of rhesus macaques infected with pathogenic SIV. IFN-α/β responses were induced during the acute phase and persisted in various lymphoid tissues throughout the chronic phase of infection. IFN-α/β responses were most consistent in tissues with high viral RNA levels; thus, IFN-α/β responses were not generally associated with effective control of SIV replication. IFN-α/β responses were differentially regulated in different lymphoid tissues and at different stages of infection. The most consistent IFN-α/β responses in acute and chronic SIV infection were observed in peripheral lymph nodes. In the spleen, only a transient increase in IFN-α/β mRNA levels during acute SIV infection was observed. Further, IFN-α and IFN-β mRNA levels showed a tissue-specific expression pattern during the chronic, but not the acute, phase of infection. In the acute phase of infection, SIV RNA levels in lymphoid tissues of rhesus macaques correlated with mRNA levels of both IFN-α and IFN-β, whereas during chronic SIV infection only increased IFN-α mRNA levels correlated with the level of virus replication in the same tissues. In lymphoid tissues of all SIV-infected monkeys, higher viral RNA levels were associated with increased Mx mRNA levels. We found no evidence that monkeys with increased Mx mRNA levels in lymphoid tissues had enhanced control of virus replication. In fact, Mx mRNA levels were associated with high viral RNA levels in lymphoid tissues of chronically infected animals.

The innate immune responses that are initiated immediately after exposure to a viral pathogen are critical in the control of viral replication and virus dissemination. The first innate effector molecules induced during the host immune response to pathogens are alpha/beta interferons (IFN-α/β) and proinflammatory cytokines. IFN-α/β are unique among the innate response molecules because they are not typically observed in bacterial or parasitic infections but are rapidly induced in viral infections. The essential in vivo role of IFN-α/β in the control of virus infections was confirmed in IFN-α/β receptor knockout mice (10, 78, 105). IFN-α/β are not only important in the early, innate response to viral infections, they are also critical for the induction and maintenance of adaptive immune responses (7, 12, 14, 28, 73, 95).

The role of IFN-α/β in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection remains a paradox. While IFN-α/β are detectable in the sera of HIV type 1 (HIV-1)-infected patients during the acute phase of infection, preceding or coincident with the peak of viremia, the presence of IFN-α/β does not prevent virus dissemination (34, 107). The presence of high serum IFN-α levels in the late stage of HIV infection is considered predictive of disease progression (37, 107). At later stages of HIV-1 infection, an aberrant, acid-labile form of IFN-α with impaired functional activity has been described (24, 49). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of HIV-1-infected patients have an impaired ability to produce IFN-α in response to in vitro virus challenge (1, 19, 31, 38-40, 110). The hyporesponsiveness of the IFN-α system observed at later stages of HIV-1 infection is associated with reduced numbers of IFN-α receptors on PBMC (68). Progression to AIDS can be accompanied by the appearance of IFN-α-resistant HIV variants in AIDS patients, suggesting that IFN-α-resistant HIV variants have a replicative advantage in the face of IFN-α responses and this leads to faster disease progression (65). But generally, progression to AIDS is accompanied by a loss of IFN-producing cells (IPC) in the blood, thus suggesting an important role of IFN-α-producing dendritic cells in the control of virus replication (27, 30, 56, 82, 102). Reduced production of IFN-α/β is associated with the development of opportunistic infections (87), and treatment with IFN-α/β, especially in the early phase of infection, reduces virus levels in HIV-1-infected patients (13, 29, 44, 46, 66, 86, 99).

It is well documented that the antiviral activity of IFN-α/β is mediated by several IFN-α/β-inducible effector molecules, e.g., 2′-5′ oligoadenylate synthetase, double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR), and Mx (23, 97, 103). These antiviral effector molecules continue to be expressed after IFN-α/β are no longer detectable (53, 54). Mx is a particularly useful indicator of IFN-α/β activity, as it is induced only by IFN-α/β and not by IFN-γ or any other cytokine (101, 109). In fact, Mx protein levels are used clinically to distinguish between viral and bacterial infections (21, 48), to assess the endogenous IFN-α/β response to a viral infection (93), and to monitor IFN treatment (4, 63, 75). Originally described in an inbred mouse strain that was inherently resistant to influenza virus (70), Mx has now been shown to exert antiviral activity against a number of RNA viruses in mice and humans (35, 47). The role of IFN-α/β-induced Mx in lentiviral infections is still unclear.

Most of the conclusions regarding the role of IFN-α/β in HIV-1 infection have been based on serum IFN-α levels and on the in vitro analysis of IFN-α/β responses in PBMC from HIV-1-infected patients. The simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) rhesus macaque model closely mimics HIV infection in humans and provides a unique opportunity to better define the role of IFN-α/β in lentiviral pathogenesis. Only limited information is available on the relationship between IFN-α/β levels and viral RNA (vRNA) levels in human lymphoid tissues. This information is critical, as lymphoid tissues are the primary site of virus replication during chronic HIV infection and changes observed in the blood may not adequately reflect IFN-α/β responses in lymphoid tissues. In a first attempt to address this question, mRNA transcript levels for IFN-α, IFN-β, and Mx were measured in lymphoid tissues of rhesus macaques chronically infected with pathogenic SIVmac239. A comparison of IFN-α/β and Mx mRNA levels in lymphoid tissues of acutely and chronically SIVmac239-infected animals defined tissue-specific differences in IFN-α/β expression levels that occur at different stages of SIV infection. Understanding how these patterns of IFN-α/β expression contribute to lentiviral pathogenesis may be important for developing interventions against HIV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) were housed at the California Regional Primate Research Center in accordance with the regulations of the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care standards. All animals were negative for antibodies to HIV-2, SIV, type D retrovirus, and simian T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1.

Infection.

The chronic infection study consisted of six monkeys (nos. 23756, 27764, 28433, 25301, 25402, and 31423) that were inoculated intravaginally (i.vag.) four times with 1 ml of SIVmac239 (104 50% tissue culture infective dose [TCID50]/ml). Blood samples were collected at weeks 1, 2, and 5 postinfection (p.i.) and at necropsy. At 6 months p.i., the monkeys were humanely killed and tissues were collected for IFN-α, IFN-β, and Mx mRNA and virus load analysis. The acute infection study consisted of two animal groups that were infected intravenously (i.v.) with either 102 TCID50 of SIVmac251 (animals no. 25317, 25363, 24882, and 25365) or 104 TCID50 of SIVmac 239 (nos. 25546, 25550, 25618, and 25605). At days 7 (nos. 25317, 25363, 25546, and 25550) and 14 (nos. 24882, 25365, 25618, and 25605) p.i., tissues were collected and analyzed for vRNA levels and for IFN-α, IFN-β, and Mx mRNA levels. Tissues from four healthy, uninfected rhesus macaques were used as control tissues.

Virus load measurement.

Total RNA isolated from various lymphoid tissues or from plasma was analyzed for vRNA by a quantitative branched DNA assay (22). Virus load in plasma samples is reported as vRNA copy number per milliliter of plasma. Tissue virus load is reported in vRNA copy numbers per 10 mg of tissue in acutely infected monkeys and per 1 μg of total tissue RNA isolated in chronically infected animals. The detection limit of this assay is 500 vRNA copies.

PBMC isolation.

PBMC were isolated from heparinized blood using lymphocyte separation medium (ICN Biomedicals, Aurora, Ohio). PBMC were immediately frozen in 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.)-90% fetal bovine serum (Gemini BioProducts, Calabasas, Calif.) and stored in liquid nitrogen until RNA isolation.

Measurement of anti-SIV antibody titers.

Anti-SIV antibody titers were measured as previously described (72).

CD4 T-cell counts.

Total lymphocyte numbers were determined by Wright/Wright-Giemsa staining (EM Science, Gibbstown, N.J.). The percentage of CD3+ CD4+ T cells was determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis on a FACScalibur with rhesus macaque-specific CD3-PerCP- and CD4-APC-labeled antibodies from Pharmingen (Pharmingen/Beckton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.). CD4 T-cell numbers were calculated by multiplying the total lymphocyte number by the percentage of CD3+ CD4+ T cells.

Tissue samples.

Blood, thymus, spleen, and peripheral, mesenteric, and genital lymph nodes were collected at the time of necropsy. Tissue samples were stored at −20°C in RNA-later (Ambion, Austin, Tex.), and frozen samples were stored at −80°C until RNA preparation (see below). Plasma was stored at −80°C. PBMC were isolated from blood as described above.

RNA isolation and cDNA preparation.

Total RNA was isolated using the Ambion RNAqueous kit (for PBMC) or the Qiagen (Valencia, Calif.) RNA Midi kit (for tissue samples). Prior to RNA isolation, the tissue samples were homogenized using a Mini-Bead Beater (Biospec Products, Inc., Bartlesville, Okla.). All samples were DNase treated with DNA-free (Ambion) for 1 h at 37°C. cDNA was prepared using random hexamer primers (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech, Inc., Piscataway, N.J.) and Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Grand Island, N.Y.).

Reverse transcriptase real-time PCR for IFN-α/β and Mx mRNA.

Real-time PCR was performed as previously described (2). Briefly, oligonucleotide primer and probe sequences were designed specifically for the TaqMan assay (2). All probes (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) were 3′-labeled with 6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine and 5′-labeled with 6-carboxyfluorescein, except for the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) probe, which was 5′-labeled with VIC (Applied Biosystems). Primers and probes were used at a final concentration of 300 and 200 nM, respectively. Samples were tested in duplicate, and the PCR for the housekeeping gene GAPDH and the target (cytokine) gene from each sample were run in parallel on the same plate. The reaction was carried out on a 96-well optical plate (Applied Biosystems) in a 25-μl reaction volume containing 5 μl of cDNA plus 20 μl of Mastermix (Applied Biosystems). All sequences were amplified using the 7700 default amplification program: 2 min at 50°C, 10 min at 95°C, followed by 40 (Mx) or 45 (IFN-α/β) cycles of 15 s at 95°C and 1 min at 60°C. Results were analyzed with the SDS 7700 system software, version 1.6.3 (Applied Biosystems) using a G4 Macintosh computer (Apple Computer, Cupertino, Calif.). Cytokine mRNA expression levels were calculated from delta cycle threshold (ΔCt) values and reported as the fold increase (FI) of cytokine mRNA levels in SIV-infected tissues compared to those in uninfected tissues. Ct values correspond to the cycle number at which the fluorescence due to enrichment of the PCR product reached significant levels above the background fluorescence (threshold). In this analysis, the Ct value for the housekeeping gene (GAPDH) is subtracted from the Ct value of the target (cytokine) gene. The ΔCt value for the SIV-infected sample is then subtracted from the ΔCt value of the corresponding uninfected sample (ΔΔCt). Assuming that the target gene (cytokine) and the reference gene (GAPDH) are amplified with the same efficiency (data not shown), the FI in SIV-infected samples compared to uninfected samples is then calculated as FI = 2−ΔΔCt (User Bulletin 2, ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System; Applied Biosystems).

Statistical analysis.

IFN-α/β and Mx mRNA levels in tissues of SIV-infected monkeys were analyzed by a one-way analysis of variance using the InStat software (GraphPad Software Inc.). Results were considered significant if P was <0.05.

RESULTS

Virologic and immunologic parameters of chronically SIVmac239-infected rhesus macaques.

Six rhesus macaques were infected i.vag. with four inoculations of SIVmac239. All monkeys became systemically infected with SIVmac239. Plasma vRNA levels peaked at week 2 p.i. and decreased by week 5, but vRNA was consistently detectable in the plasma during the 6 months of observation (Fig. 1). Once the viral setpoint was reached (week 9 p.i.), monkey 23756 had the highest plasma vRNA levels (between 7.5 and 8.5 log10 vRNA copies/ml) and the lowest anti-SIV immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody titers and CD4+ T-cell counts (Fig. 1). Among the other animals, monkeys 25402 and 31423 consistently had the lowest plasma vRNA levels (3 to 4 log10 vRNA copies/ml) and some of the highest anti-SIV IgG antibody titers and CD4+ T-cell counts (Fig. 1). As plasma vRNA levels in chronically SIV-infected macaques predict distinct clinical outcomes (50), the plasma vRNA, antibody, and CD4+ T-cell levels were consistent with the classification of monkey 23756 as a more rapid progressor, monkeys 27764, 28433, and 25301 as normal progressors, and monkeys 25402 and 31423 as nonprogressors. Further, all progressor monkeys (including the rapid progressor) had higher vRNA levels at week 24 p.i. than at week 5 p.i., whereas vRNA levels in the nonprogressor monkeys were lower at week 24 p.i. than at week 5 p.i.

FIG. 1.

Virologic and immunologic parameters of chronically SIV-infected monkeys. (A) Plasma vRNA levels of chronically SIV-infected monkeys, expressed as log10 plasma vRNA levels per milliliter of plasma, throughout the course of the study. (B) Serum anti-SIVmac251 IgG antibody titers (reported as endpoint dilutions). (C) Absolute CD4 T-cell number per microliter of blood in each individual monkey. Individual animals are represented by a distinct symbol in all panels.

At the time of necropsy, 6 months p.i., the most rapid progressor, 23756, had splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy, whereas the nonprogressor monkeys (animals 25402 and 31423) had no clinical signs or gross lesions associated with disease (data not shown). vRNA was readily detectable in lymphoid tissues (thymus, spleen, and peripheral, mesenteric, and genital lymph nodes) of animals chronically infected (6 months p.i.) with pathogenic SIVmac239 (Fig. 2). Among the tissues examined, the thymus had the lowest vRNA levels in chronic SIVmac239 infection. In the thymus and mesenteric lymph nodes of the two nonprogressor monkeys (25402 and 31423), no vRNA could be detected. These two monkeys also had the lowest vRNA levels in all other lymphoid tissues. The remaining four SIVmac239-infected monkeys (27764, 28433, 25301, and 23756) had high vRNA levels (>4 log10 vRNA copies/μg of total RNA) in all lymph nodes and spleen. Overall, the vRNA levels in lymphoid tissues of an individual monkey at 6 months p.i. correlated well with plasma vRNA levels in the same monkey (Fig. 1). Thus, the relative tissue vRNA levels among the animals were consistent with the classification of monkey 23756 as a more rapid progressor, monkeys 27764, 28433, and 25301 as normal progressors, and monkeys 25402 and 31423 as nonprogressors.

FIG. 2.

vRNA levels in lymphoid tissues of chronically SIV-infected rhesus macaques. Tissue vRNA levels are reported as log10 vRNA copies per microgram of total tissue RNA. Each bar represents an individual monkey. The same bar pattern for an individual monkey is used for results from each of the tissues.

IFN-α/β mRNA levels in PBMC of SIVmac239-infected rhesus macaques.

By week 1 p.i., two of the four progressor monkeys (23756 [rapid progressor] and 27764 [normal progressor]) had detectable plasma vRNA accompanied by normal IFN-α and IFN-β PBMC mRNA levels, but increased Mx PBMC mRNA levels (Fig. 3). Increased Mx mRNA levels persisted in PBMC of both monkeys throughout the acute phase of infection despite the absence of increased IFN-α/β mRNA levels. The rapid progressor monkey 23756 had lower Mx mRNA levels at week 2 p.i. (about a 3-fold increase) than at week 1 p.i. (about a 20-fold increase), but Mx mRNA levels were increased again at week 5 p.i. (about a 30-fold increase) and persisted at high levels throughout the chronic phase of infection. In the normal progressor monkey 27764, Mx mRNA levels peaked at the time of peak viremia (week 2 p.i.), declined by week 5 p.i., and remained low but still detectable at 6 months p.i. (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Plasma vRNA levels, IFN-α/β, and Mx mRNA levels in PBMC of SIV-infected rhesus macaques. The relationships between plasma vRNA levels and PBMC IFN-α, IFN-β, and Mx mRNA levels are shown for weeks 1, 2, 5, and 24 p.i. For each individual monkey (labels on x axis), the plasma vRNA level (black bar) and mRNA levels for IFN-α (green bar), IFN-β (blue bar), and Mx (red bar) are shown. Plasma vRNA levels are reported as log10 vRNA copies per milliliter of plasma. The mRNA levels of IFN-α, IFN-β, and Mx are reported as fold increase (FI) versus mRNA levels in matched PBMC of uninfected animals. Note that due to the different mRNA expression levels, the scales differ for each of the parameters assessed. Also, data for the rapid progressor monkey are on the far left on the x axis, and data for nonprogressor monkeys are on the far right.

The other two normal progressor monkeys (28433 and 25301) had increased IFN-α PBMC mRNA levels at week 1 p.i. despite the fact that plasma vRNA was not detectable until week 2 p.i. (Fig. 3). Thus, as has been previously described for IFN-α protein in serum (42, 59), increased IFN-α mRNA levels in PBMC preceded the detection of plasma vRNA. PBMC IFN-α mRNA levels reached their peak by week 2 p.i. in these two animals (28433 and 25301). Consistent with the induction of Mx by IFN-α/β, Mx mRNA levels were also increased by week 2 p.i. in both monkeys. Thus, increased Mx mRNA levels followed IFN-α mRNA levels in PBMC. After the peak of viremia, IFN-α and Mx mRNA levels declined in both monkeys, but PBMC IFN-α mRNA levels were slightly elevated during the chronic phase of infection (6 months p.i.), and one monkey (25301) also had increased PBMC Mx mRNA levels at 6 months p.i.

The two nonprogressors (25402 and 31423) were plasma vRNA negative and had normal IFN-α/β and Mx mRNA levels at week 1 p.i. (Fig. 3). At week 2 p.i. the monkeys had detectable plasma vRNA levels and increased PBMC Mx mRNA levels. Monkey 25402 had increased PBMC IFN-α mRNA levels at week 2 p.i. It seems likely that an increase in IFN-α mRNA levels in PBMC of monkey 31423 occurred between the sample collections at week 1 and week 2. Increased PBMC IFN-α mRNA levels in these two nonprogressors were no longer detectable by week 5 p.i. Elevated, but low, PBMC Mx mRNA levels persisted in only one monkey (25402) during the chronic phase of infection.

Consistent with the relatively low plasma vRNA levels during chronic infection, the magnitude of the increase in IFN-α and Mx mRNA levels in PBMC during chronic infection was lower than in the acute phase of SIVmac239 infection. The only exception was the rapid progressor monkey 23756, which had the highest plasma vRNA levels and PBMC Mx mRNA levels at 6 months p.i.

During both the acute and chronic phases of infection, PBMC IFN-β mRNA levels in all monkeys were indistinguishable from prechallenge levels (Fig. 3).

IFN-α/β mRNA levels in lymphoid tissues of rhesus macaques chronically infected with SIVmac239.

Despite the presence of similar, high levels of SIVmac239 vRNA in all secondary lymphoid tissues (spleen and lymph nodes) during chronic infection (6 months p.i.) (Fig. 2 and 4 ), IFN-α/β mRNA levels were increased in only a subset of these tissues (Fig. 4). In the spleen at 6 months p.i., IFN-α mRNA levels in all SIVmac239-infected animals were indistinguishable from those in normal, uninfected rhesus macaques, despite the presence of high vRNA levels (Fig. 4). No increases in IFN-β mRNA levels were detectable, except in the spleen of monkey 23756 (twofold increase), which was the most rapid progressor and had the highest vRNA levels in the spleen. Consistent with relatively low vRNA levels in the spleen at 6 months p.i., Mx mRNA levels were not increased in the spleen of the two nonprogressor monkeys (25402 and 31423). However, increased spleen Mx mRNA levels were found in all three normal progressor monkeys. The most rapid progressor had the highest increase in spleen Mx mRNA levels (14-fold increase), while monkeys 27764 and 25301 had slightly increased Mx mRNA levels (2- and 4-fold, respectively), and monkey 28433 had normal Mx mRNA levels.

FIG. 4.

vRNA levels, IFN-α/β, and Mx mRNA levels in lymphoid tissues of chronically SIV-infected rhesus macaques. The relationships between tissue vRNA levels (black bars) and tissue IFN-α, IFN-β, and Mx mRNA levels are shown for spleen, for peripheral, mesenteric, and genital lymph nodes, and for the thymus. Tissue vRNA levels are reported as log10 vRNA copies per microgram of total tissue RNA. The figure is organized as described in the legend for Fig. 3.

In all animals, the largest increase in IFN-α mRNA levels at 6 months p.i. was observed in peripheral lymph nodes (Fig. 4). The monkey that had the highest vRNA levels (rapid progressor 23756) in peripheral lymph nodes had the highest IFN-α mRNA levels in peripheral lymph nodes. The two nonprogressors (25402 and 31423) had the lowest vRNA levels in peripheral lymph nodes and had the lowest IFN-α mRNA levels. In the four animals (27764, 28433, 25301, and 23756) that had higher vRNA levels (>104 vRNA copies/μg of RNA), IFN-α mRNA levels in peripheral lymph nodes were statistically higher than mRNA levels in the same tissue of uninfected animals (P = 0.039). The Mx mRNA levels in peripheral lymph nodes directly reflected the magnitude of IFN-α mRNA levels and vRNA levels at 6 months p.i. Thus, the lowest Mx mRNA levels were observed in monkeys 25402 and 31423 (nonprogressors), intermediate levels were found in the normal progressors (27764, 28433, and 25301), and the greatest increase in Mx mRNA levels was detected in monkey 23756. At 6 months p.i., IFN-β mRNA levels were also increased in peripheral lymph nodes of four of six SIVmac239-infected animals. An unexpected finding was that the monkeys with the lowest tissue vRNA levels (nonprogressor monkeys 25402 and 31423) also had the highest IFN-β mRNA levels. In fact, the IFN-β mRNA levels in these two animals were statistically higher (P = 0.0025) than IFN-β mRNA levels in peripheral lymph nodes of uninfected animals. Among the four progressors, monkeys 23756 and 25301 had increased IFN-β mRNA levels, whereas monkeys 27764 and 28433 had normal peripheral lymph node IFN-β mRNA levels.

In mesenteric lymph nodes, IFN-α mRNA levels were only increased in the rapid progressor monkey (23756) with the highest tissue vRNA levels (Fig. 4). This monkey also had the highest Mx mRNA levels. The other three normal progressors (27764, 28433, and 25301) had high tissue vRNA levels and increased Mx mRNA levels, but normal IFN-α mRNA levels. IFN-β mRNA levels were increased in only two of the four progressors (27764 and 25301). In contrast, as was observed in peripheral lymph nodes, both nonprogressors (25402 and 31423) had statistically higher mesenteric lymph node IFN-β mRNA levels than normal monkeys (P = 0.01), but IFN-α mRNA levels in both nonprogressor monkeys were indistinguishable from normal monkeys and Mx mRNA levels were only slightly increased (threefold) in one nonprogressor monkey (31423). It should be noted, however, that in one of the progressor monkeys (27764) the increase in mesenteric lymph node IFN-β mRNA levels was comparable to that in the nonprogressor monkeys. The slight increase in Mx mRNA levels in one of two nonprogressors and the presence of increased IFN-β mRNA levels in both nonprogressors was indicative of some virus replication in the mesenteric lymph nodes of these two monkeys. Indeed, although no vRNA was detected, the mesenteric lymph nodes of both monkeys tested PCR positive for SIVgag and SIVenv DNA (data not shown).

In genital lymph nodes, IFN-α mRNA levels were increased in three of the four progressors (23756, 28433, and 25301) with higher vRNA levels, but not in the tested nonprogressor (31423) (Fig. 4). No sample was available for the nonprogressor 25402 with lower vRNA levels. Genital lymph node IFN-β mRNA levels were normal in all monkeys. Consistent with the higher vRNA levels and increased IFN-α mRNA levels, all the normal progressor monkeys also had increased genital lymph node Mx mRNA levels that were not observed in the nonprogressor (31423). The greatest increase in genital lymph node Mx mRNA levels was detected in the most rapid progressor (23756) that had the highest vRNA and IFN-α mRNA levels in this tissue.

Among the tissues examined, the thymus had the lowest vRNA levels in all monkeys, with no vRNA detectable in the thymus of the nonprogressor monkeys (25402 and 31423) (Fig. 4). However, one of the two nonprogressors (31423) had slightly elevated IFN-α (3.5-fold) and IFN-β (3-fold) thymus mRNA levels, but normal Mx mRNA levels. Increased thymus IFN-α mRNA levels were detected in three of four normal progressors, and two monkeys (28433 and 25301) had increased IFN-β mRNA levels. All of the normal progressors had increased Mx mRNA levels. The monkey with the highest thymus vRNA levels (rapid progressor 23756) had the highest IFN-α and Mx mRNA levels. Interestingly, the increase seen in thymus Mx mRNA levels in the four progressors was comparable to the increase of Mx mRNA levels observed in spleen and genital lymph nodes, tissues with considerably higher vRNA levels.

In summary, PBMC IFN-α mRNA levels were markedly increased during the acute phase of SIVmac239 infection (days 7 or 14 p.i.), but only in three of six animals. The most likely explanation for this finding is that our sampling schedule missed the increase in IFN-α mRNA levels in the other three monkeys. During the chronic phase of infection (6 months p.i.), only two of six monkeys had slightly increased IFN-α mRNA levels. In contrast, increased Mx PBMC mRNA levels persisted throughout the acute (six of six monkeys), subacute (week 5 p.i.; five of six monkeys), and chronic (6 months p.i., four of six monkeys) phases of SIV infection. Thus, increased Mx, and not IFN-α, PBMC mRNA levels were a reliable indicator of ongoing SIV replication in chronically SIV-infected rhesus macaques. Further, and consistent with the earlier detection of plasma vRNA and higher plasma vRNA levels in normal progressors, increased PBMC IFN-α and Mx mRNA levels were also more rapidly induced in normal progressors than in nonprogressors. Thus, early control of viral replication mediated by increased IFN-α/β mRNA levels in PBMC does not seem to be a feature of nonprogressors.

During chronic SIVmac239 infection (6 months p.i.), IFN-α/β responses were consistently observed in lymphoid tissues, but not in PBMC. This observation is consistent with the fact that lymphoid organs serve as the primary site of virus replication during chronic infection. It should be noted that although increased IFN-β mRNA levels were never detectable in PBMC of any of the SIVmac239-infected animals, several monkeys had increased IFN-β mRNA levels in lymphoid tissues. Further, there was a distinct anatomic distribution of IFN-α and IFN-β responses. The increase in IFN-α/β mRNA levels induced by chronic SIVmac239 infection was smallest in the spleen (no increase in IFN-α) and greatest in peripheral lymph nodes (highest increase in IFN-α). In genital lymph nodes IFN-α, but not IFN-β, mRNA levels were increased, whereas in the mesenteric lymph nodes increased IFN-β mRNA levels, but not IFN-α mRNA levels, were detected. In the thymus, four of six and three of six monkeys had increased IFN-α and IFN-β mRNA levels, respectively. In peripheral and genital lymph nodes and thymus, monkeys with higher vRNA levels (progressors 23756, 27764, 28433, and 25301) also had higher IFN-α and Mx mRNA levels than nonprogressors (25402 and 31423). In tissues of nonprogressors with increased IFN-β mRNA levels, there was not an associated increase in tissue IFN-α mRNA levels, but these tissues had lower vRNA levels. The fact that some tissues with high vRNA levels also had high IFN-α mRNA levels (peripheral and genital lymph node) but other tissues with high vRNA had low or undetectable IFN-α mRNA levels (spleen and mesenteric lymph node) suggested that expression of IFN-α is not sufficient to control virus replication in lymphoid tissues of chronically SIV-infected animals.

As was observed in PBMC at 6 months p.i., Mx mRNA levels most consistently correlated with the levels of vRNA in lymphoid tissues (Fig. 4). All animals with actively replicating virus in lymphoid tissues also had increased levels of Mx mRNA in most lymphoid tissues. The animal (23756) that had the highest vRNA levels in all lymphoid tissues also had higher Mx mRNA levels than all other monkeys studied. The two nonprogressor monkeys that had the lowest Mx mRNA levels in all lymphoid tissues (25402 and 31423) also had the lowest vRNA levels. In fact, Mx mRNA levels in all lymphoid tissues of the four animals with higher vRNA levels (monkeys 27764, 28433, 25301, and 23756) were significantly higher (P < 0.05) than Mx mRNA levels in the same tissues of naive animals. Further, the magnitude of tissue Mx mRNA levels correlated with the relative level of virus replication in all six SIVmac239-infected monkeys.

IFN-α/β mRNA levels in lymphoid tissues of rhesus macaques acutely infected with SIVmac239.

The above data suggested that IFN-α/β responses were induced during the acute phase of infection and persisted in lymphoid tissues throughout the chronic phase of infection. However, there were tissue-specific patterns of IFN-α/β expression at 6 months p.i. Therefore, we sought to determine if the tissue-specific differences observed in IFN-α/β responses were limited to the chronic stage of SIV infection or developed in the acute phase of infection.

No longitudinal biopsy samples were available from the chronically SIVmac239-infected monkeys described above. Indeed, biopsies of peripheral lymph nodes would not be useful for addressing the timing of tissue-specific IFN-α/β mRNA expression patterns in SIV infection. However, lymphoid tissues from i.v. SIVmac239-infected rhesus macaques that were euthanized during the acute phase of infection were available. We have previously shown that although there is a delay in peak viremia in i.vag. SIV-inoculated monkeys compared to i.v. inoculated monkeys, once systemic infection is established the clinical course is the same regardless of the inoculation route (76, 77). Thus, the same tissues that were analyzed in the chronically SIVmac239-infected monkeys described above (spleen, peripheral lymph nodes, and thymus) were collected from SIVmac239-infected animals on days 7 and 14 p.i., and IFN-α/β, Mx mRNA levels, and vRNA levels were determined. Infection of rhesus macaques with cloned SIVmac239 and uncloned SIVmac251 result in a similar disease course (unpublished observation). Therefore, to increase the number of tissues available at each time point, the lymphoid tissues from SIVmac251-infected animals were included in the analysis.

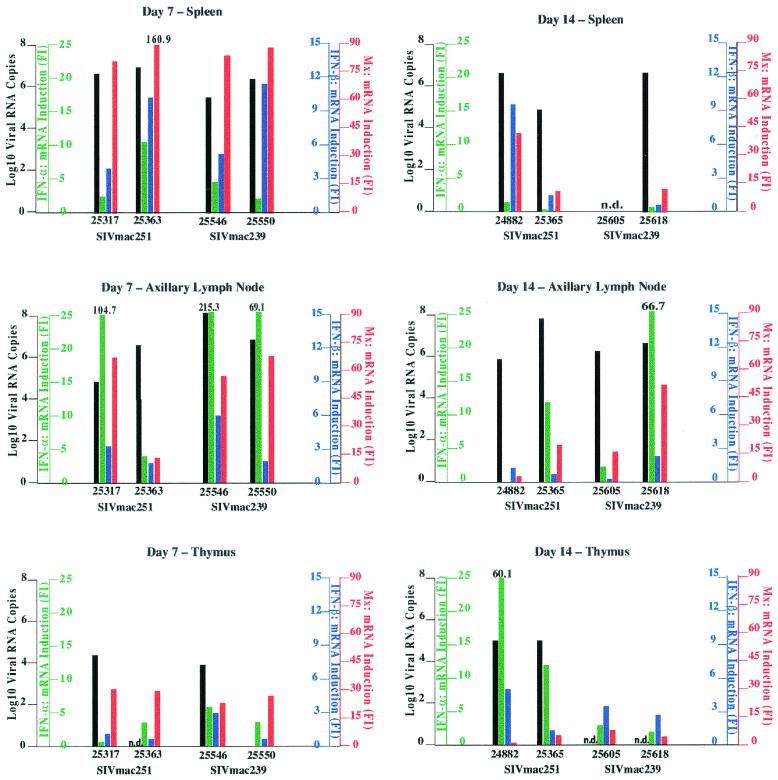

Four monkeys were infected i.v. with either cloned SIVmac239 or uncloned SIVmac251. The animals were euthanized on days 7 and 14 (n = 2 animals/day/virus) during the acute phase of infection. Plasma vRNA levels were low on day 3 and reached peak levels between days 7 and 14 (data not shown). Consistent with high vRNA levels in plasma, high tissue vRNA levels were observed in spleens and axillary lymph nodes of all monkeys. As was observed in chronic infection, the lowest vRNA levels were seen in the thymus. It should be noted that the plasma (data not shown) and tissue vRNA levels were similar in both groups of SIVmac239- and SIVmac251-infected animals despite the different inoculation doses (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

vRNA levels, IFN-α/β, and Mx mRNA levels in lymphoid tissues of acutely SIV-infected rhesus macaques. The relationships between tissue vRNA levels and tissue IFN-α, IFN-β, and Mx mRNA levels are shown for spleen, peripheral lymph nodes, and thymus on day 7 and day 14 p.i. Tissue vRNA levels are reported as log10 vRNA copies per 10 mg of tissue. The figure is organized as described in the legend for Fig. 3.

In marked contrast to the finding in chronically SIV-infected monkeys, the high vRNA levels in the spleen of acutely SIV-infected animals were accompanied by increased IFN-α/β mRNA levels (Fig. 5). However, the induction of IFN-α/β mRNA in the spleen was transient and only detectable on day 7 p.i., when four of four monkeys had increased IFN-α and IFN-β mRNA levels. By day 14 p.i., only one of three SIV-infected monkeys (24882) had increased IFN-β mRNA levels and all three animals had normal spleen IFN-α mRNA levels. It should be noted that the severalfold increase in spleen IFN-β mRNA levels was higher than the increase in spleen IFN-α mRNA levels. Consistent with the transient expression of IFN-α/β, Mx mRNA levels reached the highest levels in four of four monkeys on day 7 p.i. On day 14, however, the increase in spleen Mx mRNA levels was lower than on day 7, but all three monkeys had increased Mx mRNA levels. A positive correlation between spleen IFN-α/β and Mx mRNA levels in the acute but not the chronic phase of SIV infection was confirmed by linear regression analysis (data not shown).

As was observed in the tissues of chronically SIV-infected monkeys, the increase in IFN-α mRNA levels in acute SIV infection was highest and most consistent in peripheral lymph nodes (Fig. 5). Four of four animals had increased IFN-α mRNA levels in the axillary lymph node on day 7, and on day 14 p.i. two of three animals had elevated IFN-α mRNA levels (Fig. 5). All animals with increased IFN-α mRNA levels also had increased Mx mRNA levels in peripheral lymph nodes. In fact, linear regression analysis showed that there was a positive correlation between IFN-α and Mx mRNA levels in the peripheral lymph nodes of acutely SIV-infected monkeys. This correlation was also present in chronically SIV-infected monkeys (data not shown). Peripheral lymph node IFN-β mRNA levels were increased in only two of four monkeys (25317 and 25546) on day 7, but by day 14 they were indistinguishable from the IFN-β mRNA levels in matched tissues of uninfected animals.

In the thymus on day 7, despite lower vRNA levels than in spleen and axillary lymph nodes (note: no sample was available for monkey 25363, and monkey 25550 was negative for vRNA), increased IFN-α, but not IFN-β, mRNA levels were detectable in three of four monkeys (Fig. 5). All animals also had increased Mx mRNA levels on day 7 p.i. It is unclear why the monkey with undetectable vRNA (25550) had increased IFN-α and increased Mx mRNA levels at this time point. Earlier reports have shown, however, that viral proteins in the absence of viral replication are sufficient to induce IFN-α/β and Mx (16, 33, 41, 43, 52, 111). On day 14, thymus IFN-α mRNA levels were increased in three of four animals (Fig. 5), and IFN-β mRNA levels were slightly increased in three of four monkeys (Fig. 5) (no samples were available for vRNA testing from the two SIVmac239-infected monkeys). Consistent with increased thymus IFN-α/β mRNA levels on day 14, thymus Mx mRNA levels were also increased in three of four monkeys (25365, 25605, and 25618). One monkey (24882) that had high thymus vRNA levels and the highest increase in IFN-α mRNA levels on day 14 had thymus Mx mRNA levels that were undistinguishable from uninfected monkeys. In general, thymus Mx mRNA levels seemed to be higher on day 7 than on day 14, but careful interpretation of these data is warranted because all data points were from individual animals, as longitudinal tissue sampling is difficult from the thymus. It is conceivable that the peak of Mx mRNA levels was not yet reached in animal 24882, because this animal had high thymus IFN-α mRNA levels that preceded peak Mx mRNA levels.

In summary, in contrast to chronic infection, all tissues examined had increased IFN-α and IFN-β mRNA levels during the acute phase of infection. Consistent with this, in all tissues of acutely SIV-infected monkeys except the spleen (P = 0.1), IFN-α mRNA levels were significantly higher (P < 0.04) than IFN-α mRNA levels in matched tissues of uninfected animals. Further, as was observed in chronic SIV infection, the IFN-α/β-inducible antiviral effector molecule Mx was also consistently expressed at significantly higher (P < 0.025) mRNA levels in lymphoid tissues of acutely SIV-infected animals compared to naïve, uninfected animals. A common finding in both acute and chronic SIV infection was that the magnitude of the induction of IFN-α mRNA was lowest in the spleen and highest in the peripheral lymph nodes.

DISCUSSION

Once established, lentiviral infections in humans and rhesus macaques are never eliminated; instead, a chronic infection develops that usually culminates in AIDS. The duration of the chronic, often asymptomatic, phase of infection with a pathogenic virus is greatly influenced by host immune responses. In recent years, much work has been done demonstrating the role of adaptive cellular antiviral immune responses in control of virus replication (69, 91, 96). Far less is known about the role and importance of innate immune mechanisms in the control of virus replication in chronic lentiviral infections. In HIV-1 infection, IFN-α is detectable in the serum during the acute phase of infection, reduced to normal levels during the asymptomatic phase, and increased again in the serum at the time of disease progression and opportunistic infections (34, 37, 107). Very limited information is available on IFN-α/β responses in lymphoid tissues during chronic HIV and SIV infections (58, 59). This information is necessary because lymphoid tissues are the sites of active virus replication during the chronic phase of HIV and SIV infection (83, 84, 92).

The results from the current study show that IFN-α/β responses are induced in the acute phase of SIV infection and persist in various lymphoid tissues throughout the chronic phase of SIV infection, but these responses are not sufficient to control SIV replication. During the acute phase of infection, at week 1 p.i., PBMC IFN-α/β responses were only detectable in the progressor monkeys. In progressor monkeys with detectable plasma vRNA at week 1 p.i., increased PBMC Mx mRNA levels, but not IFN-α mRNA levels, were detectable, and in progressor monkeys with undetectable plasma vRNA, PBMC IFN-α mRNA levels but not Mx mRNA levels were increased. All monkeys had increased PBMC Mx mRNA levels at the time of peak viremia (week 2 p.i. for these i.vag. inoculated animals). These findings are most consistent with the interpretation that increases in PBMC IFN-α mRNA levels precede plasma vRNA levels and increased PBMC Mx mRNA levels. Indeed, it has been shown previously that IFN-α protein is detectable in the sera of SIV-infected macaques as early as day 3 (42, 59), whereas vRNA is not detectable before week 1. The fact that PBMC IFN-α/β responses were seen earlier in progressor monkeys than in nonprogressor monkeys implied that early control of viral replication by expression of IFN-α/β in PBMC was not a characteristic of nonprogressor monkeys. At 6 months p.i., increased PBMC IFN-α mRNA levels were detectable in only two of six monkeys. These results (on the mRNA level) indirectly support findings in HIV-1-infected patients demonstrating reduced IFN-α production in PBMC (19, 31, 38-40, 110) and of low or undetectable IFN-α levels in the sera of chronically HIV-infected patients (34, 64). Similarly, it has been shown in SIV-infected monkeys that serum IFN-α levels are undetectable during the chronic, asymptomatic phase of infection (67).

In the present study, increased PBMC IFN-β mRNA levels were not detected during the acute or chronic phase of infection.

In contrast to PBMC, increased mRNA levels of both IFN-α and IFN-β and the IFN-α/β-induced antiviral effector molecule Mx were readily detectable in lymphoid tissues of acutely and chronically SIV-infected monkeys. A comparative analysis of IFN-α/β mRNA levels in lymphoid tissues of acutely and chronically SIV-infected monkeys revealed that IFN-α/β interferon responses are differentially regulated in different lymphoid tissues and that these tissue-specific differences in IFN-α/β mRNA levels may contribute to SIV pathogenesis. In the spleen, increased IFN-α/β mRNA levels were only detected at the time of peak viremia (day 7 in these i.v. inoculated animals). The transient nature of the IFN-α response in the spleen (undetectable by day 14 and during chronic infection), despite persistently high spleen vRNA levels throughout the course of infection, suggested that IFN-α/β responses are not maintained in the spleen during chronic SIV infection. Thus, IFN-α/β responses most likely do not contribute to the control of virus replication in the spleen of chronically SIV-infected animals. Because baseline IFN-α mRNA levels in spleens of uninfected animals are relatively high compared to those in peripheral lymph nodes, the magnitude of increase is less in spleen during the acute phase (2). In the chronic phase, although IFN-α mRNA levels are similar to those of uninfected animals, this baseline level of IFN-α expression may have some effect on viral replication. The role of the spleen in HIV pathogenesis is still poorly understood (60). In some cases, splenectomy in HIV-infected patients has resulted in an improved disease course (9, 104), and lower virus burdens have been also observed in splenectomized SIV-infected rhesus macaques (55).

The most consistent IFN-α/β responses in both the acute and chronic stages of SIV infection were observed in peripheral lymph nodes. Peripheral lymph node IFN-α and IFN-β mRNA and vRNA reached peak levels on day 7. These results are consistent with previous studies reporting the appearance of IFN-α-positive cells in lymph nodes of SIVmac251-infected monkeys as early as day 4 (59). However, the simultaneous persistence of increased peripheral lymph node IFN-α mRNA levels and high vRNA levels in peripheral lymph nodes at all stages of SIV infection suggests that increased IFN-α mRNA levels do not contribute to effective control of virus replication.

In the thymus, a primary lymphoid organ, elevated IFN-α/β mRNA levels persisted throughout the acute and chronic phases of infection. The magnitude of the increase in IFN-α/β mRNA levels during chronic SIV infection was similar to the increase observed in some of the secondary lymphoid organs that had significantly higher levels of virus replication than the thymus. Thus, increased IFN-α/β mRNA levels in the thymus were associated with relative control of virus replication in the thymus.

In a lymphoid tissue sample from an individual animal during acute SIV infection, both IFN-α and IFN-β mRNA levels were increased, but during chronic SIV infection increased IFN-α and IFN-β mRNA levels were found in distinct lymphoid tissues. In the spleen, the increase of IFN-β mRNA levels in acute SIV infection was higher than the increase in IFN-α mRNA levels, but both IFN-α and IFN-β mRNA levels in the spleen were normal during the chronic stage of infection. In contrast, in peripheral lymph nodes and thymus, increased IFN-α and IFN-β mRNA levels were found during both the acute and chronic phases of infection. During acute SIV infection, the increase of IFN-α mRNA levels was higher than the increase of IFN-β mRNA levels within the same tissue. A striking finding was that during chronic SIV infection IFN-β, but not IFN-α, mRNA levels were increased in mesenteric lymph nodes. In contrast, increased IFN-α, but not IFN-β, mRNA levels were characteristic in genital lymph nodes. Thus, IFN-α and IFN-β mRNA levels may be differentially regulated at different stages of SIV infection and in different anatomic compartments. Despite the same receptor usage (97), distinct in vivo functions for IFN-α and IFN-β due to differences in the intracellular signaling pathways for IFN-α and IFN-β have been proposed (11, 26, 32, 85, 89).

In the present study, the two nonprogressor monkeys (with the lowest vRNA levels in all tissues) had significantly higher IFN-β mRNA levels in peripheral and mesenteric lymph nodes compared to IFN-β mRNA levels in the same tissues of uninfected animals. In addition, IFN-α mRNA levels in these tissues were low or normal. This observation suggests an effective role for IFN-β, but not IFN-α, in control of virus replication. This interpretation is further supported by the finding that cynomolgous macaques transfused with IFN-β-transduced PBMC have enhanced resistance to challenge with pathogenic SIVmac251 compared to control animals (74). Similarly, the transduction of PBMC from HIV-1-infected patients with IFN-β resulted in increased T helper 1 responses in vitro (106). However, treatment of HIV-1-infected patients with IFN-β alone had no effect on virus replication (80, 81) but was beneficial when given in combination with zidovudine (79).

In contrast to IFN-β, higher IFN-α mRNA levels were found in lymphoid tissues of progressor monkeys than in the nonprogressor monkeys during the chronic phase of SIV infection. During the chronic phase of infection, in the lymphoid tissues that had increased IFN-α mRNA levels, these levels correlated with vRNA levels. Thus, in the thymus and in peripheral and genital lymph nodes, progressor monkeys had higher vRNA levels and higher IFN-α mRNA levels than the nonprogressor monkeys. In the mesenteric lymph nodes, increased IFN-α mRNA levels were only detectable in the most rapid progressor with the highest vRNA levels in this tissue.

The magnitude of the increase in IFN-α mRNA levels was paralleled by Mx mRNA levels in lymphoid tissues. This positive correlation between IFN-α and Mx mRNA levels and vRNA levels was apparent in the acute and chronic phases of infection. In all animals, PBMC and tissue IFN-α and Mx mRNA levels reached peak levels just before or around the time of peak viremia and then declined slightly. In general, and consistent with lower vRNA levels, IFN-α/β mRNA levels were lower in PBMC and lymphoid tissues in the chronic phrase compared to the acute phase of infection. In PBMC of all chronically SIV-infected monkeys, Mx but not IFN-α/β mRNA levels were a reliable marker of ongoing virus replication. Consistent with these results, it was shown in a group of HIV-infected patients that only a minority of the patients had elevated IFN-α plasma levels, whereas almost all of the patients had increased Mx protein levels in their PBMC (108). In addition, the level of PBMC-associated Mx protein correlated with the disease stage of the patient (20, 108). As we have shown for the monkeys in the present study, the rapid HIV progressors had higher Mx levels than slow progressors (108).

Increased Mx mRNA levels were consistently detected in all the lymphoid tissues from animals chronically infected with SIVmac239 that had detectable vRNA levels, even if IFN-α mRNA levels were normal. In lymphoid tissues of chronically SIV-infected monkeys, increased Mx mRNA levels were strongly associated with increased vRNA levels. Thus, there is no evidence for enhanced control of viral replication in monkeys expressing high levels of the IFN-α/β-inducible antiviral effector molecule Mx. HIV proteins can interfere with the antiviral activity of IFN-α/β (88, 98). HIV-1 tat can inhibit PKR, an antiviral effector molecule that, like Mx, is induced by IFN-α/β (94). Monocytes from HIV-infected patients can produce Mx after in vitro HIV infection and thereby effectively prevent superinfection of these cells by other viruses without interfering with the replication of HIV (6). It has recently been demonstrated that Mx had no inhibitory effect on the replication of another complex human retrovirus (90). In a direct in vitro comparison, it was shown that IFN-induced promyelocytic leukemia protein, but not IFN-induced Mx, repressed the transcription of human foamy virus (90). Thus, it will be important to test the relationship between multiple IFN-α/β-induced molecules and vRNA levels in SIV infection to more clearly determine the role of IFN-α/β and their antiviral effector molecules in the control of SIV replication.

Further, the relative levels of vRNA and Mx mRNA levels found in lymphoid tissues in chronically infected animals were reflected in their PBMC Mx mRNA levels. Thus, PBMC Mx mRNA levels in chronically SIV-infected monkeys are an indirect indicator of virus replication in lymphoid tissues and could potentially be used as a marker of disease progression in lentiviral infections.

The discrepancies in the temporal relationship between viral replication, IFN-α/β mRNA, and Mx mRNA production in PBMC and lymphoid tissues can be explained by the sequential expression of the relevant genes. Virus infection of cells is followed within hours by IFN-α/β gene expression and then by induction of Mx mRNA (3, 51). Furthermore, expression of IFN-α/β is transient, while Mx continues to be expressed after IFN-α/β are no longer detectable (53, 54). In addition, Mx can be induced independently of IFN-α/β in monocytes isolated from HIV-1-infected patients (6). In fact, viral proteins alone, in the absence of viral replication, can induce Mx (43, 52). However, in lymphoid tissues of chronically SIV-infected monkeys with increased IFN-α mRNA levels, the magnitude of the increase in IFN-α mRNA paralleled the magnitude of the increase in Mx mRNA levels. Similarly, it has been demonstrated that the HIV envelope protein gp120 can lead to the direct induction of IFN-α and IFN-β (16, 33, 41, 111). Thus, virus replication-dependent and/or -independent mechanisms can induce expression of IFN-α/β and Mx, and this may have contributed to increased IFN-α/β and Mx mRNA levels in the various lymphoid tissues examined in this study.

It has been reported recently that HIV disease progression is associated with a loss of IPC in peripheral blood (27, 30, 56, 82, 102), and the loss of IFN-α production inversely correlates with virus burden and the development of opportunistic infections (99, 100). During viral infection, IPC preferentially migrate to the T-cell zones in secondary lymphoid tissues, where they also promote T helper 1 responses that are essential in antiviral immunity (5, 17, 18, 71). Therefore, it will be critical to determine if the various IFN-α mRNA levels observed in different lymphoid tissues during SIV infection are due to differences in the number and/or functional characteristics of IPC present in these tissues. Recently, IPC have been described in the thymus (8, 58). Consistent with this finding, we found relatively high IFN-α mRNA levels in the thymus despite relatively low vRNA levels. It has similarly been shown that HIV infection leads to induction of innate immune responses in the thymus, but that this response is not sufficient to control virus replication completely (58). The thymus has been identified as another major reservoir of virus replication during chronic HIV infection (15, 62), and immature thymocytes express higher numbers of IFN-α receptors than mature T cells (58). Thus, it is possible that infected thymocytes are more receptive to the antiviral effects of IFN-α than HIV and SIV target cells found in secondary lymphoid organs. Hyporesponsiveness to IFN-α due to decreased IFN-α receptor expression has also been described in PBMC of HIV-infected patients (68). Thus, the number of IFN-α receptors in different lymphoid tissues also needs to be examined in future studies.

The lack of control of virus replication in the presence of high IFN-α mRNA levels could be due to the development of IFN-α-resistant HIV variants. However, in HIV-1-infected patients, no correlation could be established between the in vitro resistance to IFN-α and actual in vivo serum IFN-α levels (65). Further, based on the present study it is unlikely that distinct anatomic compartments harbor distinct SIV variants with different degrees of IFN-α resistance. An aberrant, acid-labile form of IFN-α with impaired functional activity has been described at later stages of HIV-1 infection (24, 49). In the present study only mRNA levels of IFN-α were evaluated, but the actual type of IFN-α protein produced was not determined. Thus, it is possible that in some lymphoid tissues no control of virus replication in the presence of high IFN-α mRNA levels was observed, because the IFN-α protein produced in the same tissues was not functionally active. However, acid-labile IFN-α has not been detected in SIV-infected animals (67), and in HIV-1-infected patients the in vitro production of acid-labile IFN-α did not correlate with the in vivo detection of acid-labile IFN-α (31).

Finally, our analysis of IFN-α mRNA levels was limited to assessing the transcripts of the IFN-α2 gene. IFN-α2 was selected because it is approved worldwide for the treatment of viral infections and various cancers (45, 57). In addition, it has been shown that treatment of HIV-1-infected patients with IFN-α2a resulted in reduced levels of plasma vRNA levels (36). There are, however, more than 20 IFN-α subtypes that are encoded by different genes (25). The exact function and tissue distribution of these IFN-α subtypes is not known and requires additional studies.

This study provides some initial insight into the role of innate immune responses in controlling primate lentiviral infections. It has been shown previously that IFN-α/β inhibit HIV and SIV replication at different steps in the replication cycle (61). Therefore, a more detailed understanding of IFN-α/β responses is essential to use of the SIV model effectively as a model for HIV infection. A better understanding of the relationship between innate antiviral immunity and SIV pathogenesis may be critical to developing antiviral therapies and vaccines capable of stopping the HIV pandemic.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Science grant RR00169 and grant RR14555 (C.J.M.) from the National Center for Research Resources; AI39435 (C.J.M.), AI35545 (C.J.M.), and AI39109 (M.M.) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; and the Elizabeth Glaser Scientist award 8-97 (M.M.) from the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation.

We thank Neil Willits of the Department of Statistics at UC Davis for help with the statistical analysis and Kimberly Schmidt and Kenneth Zanotto for technical assistance. We are grateful to M. McChesney and J. and M. Torten for helpful discussions of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abb, J., M. Kochen, and F. Deinhardt. 1984. Interferon production in male homosexuals with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) or generalized lymphadenopathy. Infection 12:240-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abel, K., M. J. Alegria-Hartman, K. Zanotto, M. B. McChesney, M. L. Marthas, and C. J. Miller. 2001. Anatomic site and immune function correlate with relative cytokine mRNA expression levels in lymphoid tissues of normal rhesus macaques. Cytokine 16:191-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abrams, M. E., M. J. Balish, and C. R. Brandt. 1995. IFN-alpha induces MxA gene expression in cultured human corneal fibroblasts. Exp. Eye Res. 60:137-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antonelli, G., E. Simeoni, O. Turriziani, R. Tesoro, A. Redaelli, L. Roffi, L. Antonelli, M. Pistello, and F. Dianzani. 1999. Correlation of interferon-induced expression of MxA mRNA in peripheral blood mononuclear cells with the response of patients with chronic active hepatitis C to IFN-alpha therapy. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 19:243-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asselin-Paturel, C., A. Boonstra, M. Dalod, I. Durand, N. Yessaad, C. Dezutter-Dambuyant, A. Vicari, A. O'Garra, C. Biron, F. Briere, and G. Trinchieri. 2001. Mouse type I IFN-producing cells are immature APCs with plasmacytoid morphology. Nat. Immunol. 2:1144-1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baca, L. M., P. Genis, D. Kalvakolanu, G. Sen, M. S. Meltzer, A. Zhou, R. Silverman, and H. E. Gendelman. 1994. Regulation of interferon-alpha-inducible cellular genes in human immunodeficiency virus-infected monocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 55:299-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belardelli, F., and I. Gresser. 1996. The neglected role of type I interferon in the T-cell response: implications for its clinical use. Immunol. Today 17:369-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bendriss-Vermare, N., C. Barthelemy, I. Durand, C. Bruand, C. Dezutter-Dambuyant, N. Moulian, S. Berrih-Aknin, C. Caux, G. Trinchieri, and F. Briere. 2001. Human thymus contains IFN-alpha-producing CD11c(−), myeloid CD11c(+), and mature interdigitating dendritic cells. J. Clin. Investig. 107:835-844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernard, N. F., D. N. Chernoff, and C. M. Tsoukas. 1998. Effect of splenectomy on T-cell subsets and plasma HIV viral titers in HIV-infected patients. J. Hum. Virol. 1:338-345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Binder, D., J. Fehr, H. Hengartner, and R. M. Zinkernagel. 1997. Virus-induced transient bone marrow aplasia: major role of interferon-alpha/beta during acute infection with the noncytopathic lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. J. Exp. Med. 185:517-530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biron, C. A. 2001. Interferons alpha and beta as immune regulators—a new look. Immunity 14:661-664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biron, C. A. 1998. Role of early cytokines, including alpha and beta interferons (IFN-α/β), in innate and adaptive immune responses to viral infections. Semin. Immunol. 10:383-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bizzini, B., I. Volpato, A. Lachgar, P. Cohen, and A. Gringeri. 1999. IFN alpha kinoid vaccine in conjunction with tritherapy, a weapon to combat immunopathogenesis in AIDS. Biomed. Pharmacother. 53:87-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brinkmann, V., T. Geiger, S. Alkan, and C. H. Heusser. 1993. Interferon alpha increases the frequency of interferon gamma-producing human CD4+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 178:1655-1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brooks, D. G., S. G. Kitchen, C. M. Kitchen, D. D. Scripture-Adams, and J. A. Zack. 2001. Generation of HIV latency during thymopoiesis. Nat. Med. 7:459-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Capobianchi, M. R., F. Ameglio, P. Cordiali Fei, C. Castilletti, F. Mercuri, S. Fais, and F. Dianzani. 1993. Coordinate induction of interferon alpha and gamma by recombinant HIV-1 glycoprotein 120. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 9:957-962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cella, M., F. Facchetti, A. Lanzavecchia, and M. Colonna. 2000. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells activated by influenza virus and CD40L drive a potent TH1 polarization. Nat. Immunol. 1:305-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cella, M., D. Jarrossay, F. Fachetti, O. Alebardi, H. Nakajima, A. Lanzavecchia, and M. Colonna. 1999. Plasmacytoid monocytes migrate to inflamed lymph nodes and produce large amounts of type 1 interferon. Nat. Med. 5:919-923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chehadeh, W., S. Chabou, C. Fontier, G. Alm, G. Lion, L. Bocket, Y. Mouton, P. Wattre, and D. Hober. 2000. In HIV-1-infected patients, plasma levels of HIV-1 RNA are inversely correlated with IFN-alpha responsiveness of whole-blood cultures to Sendai virus. J. Clin. Virol. 16:123-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chehadeh, W., D. Hober, V. Chieux, G. Alm, J. Harvey, G. Lion, Y. Mouton, and P. Wattre. 1999. Biological properties of interferon-alpha produced ex vivo by whole blood of patients infected by human immunodeficiency virus-1. Scand. J. Immunol. 49:660-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chieux, V., D. Hober, J. Harvey, G. Lion, D. Lucidarme, G. Forzy, M. Duhamel, J. Cousin, H. Ducoulombier, and P. Wattre. 1998. The MxA protein levels in whole blood lysates of patients with various viral infections. J. Virol. Methods 70:183-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dailey, P. J., M. Zamround, R. Kelso, J. Kolberg, and M. Urdea. 1995. Quantitation of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) RNA in plasma of acute and chronically infected macaques using a branched DNA (bDNA) signal amplification assay. J. Med. Primatol. 24:209. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Der, S. D., A. Zhou, B. R. Williams, and R. H. Silverman. 1998. Identification of genes differentially regulated by interferon alpha, beta, or gamma using oligonucleotide arrays. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:15623-15628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeStefano, E., R. M. Friedman, A. E. Friedman-Kien, J. J. Goedert, D. Henriksen, O. T. Preble, J. A. Sonnabend, and J. Vilcek. 1982. Acid-labile human leukocyte interferon in homosexual men with Kaposi's sarcoma and lymphadenopathy. J. Infect. Dis. 146:451-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diaz, M. O., S. Bohlander, and G. Allen. 1993. Nomenclature of human interferon genes. J. Interferon Res. 13:243-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Domanski, P., O. W. Nadeau, L. C. Platanias, E. Fish, M. Kellum, P. Pitha, and O. R. Colamonici. 1998. Differential use of the βL subunit of the type I interferon (IFN) receptor determines signaling specificity for IFN-α2 and IFN-β. J. Biol. Chem. 273:3144-3147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donaghy, H., A. Pozniak, B. Gazzard, N. Qazi, J. Gilmour, F. Gotch, and S. Patterson. 2001. Loss of blood CD11c(+) myeloid and CD11c(−) plasmacytoid dendritic cells in patients with HIV-1 infection correlates with HIV-1 RNA virus load. Blood 98:2574-2576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Durbin, J. E., A. Fernandez-Sesma, C. K. Lee, T. D. Rao, A. B. Frey, T. M. Moran, S. Vukmanovic, A. Garcia-Sastre, and D. E. Levy. 2000. Type I IFN modulates innate and specific antiviral immunity. J. Immunol. 164:4220-4228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Emilie, D., M. Burgard, C. Lascoux-Combe, M. Laughlin, R. Krzysiek, C. Pignon, A. Rudent, J. M. Molina, J. M. Livrozet, F. Souala, G. Chene, L. Grangeot-Keros, P. Galanaud, D. Sereni, and C. Rouzioux. 2001. Early control of HIV replication in primary HIV-1 infection treated with antiretroviral drugs and pegylated IFN alpha: results from the Primoferon A (ANRS 086) Study. AIDS 15:1435-1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feldman, S., D. Stein, S. Amrute, T. Denny, Z. Garcia, P. Kloser, Y. Sun, N. Megjugorac, and P. Fitzgerald-Bocarsly. 2001. Decreased interferon-alpha production in HIV-infected patients correlates with numerical and functional deficiencies in circulating type 2 dendritic cell precursors. Clin. Immunol. 101:201-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferbas, J., J. Navratil, A. Logar, and C. Rinaldo. 1995. Selective decrease in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-induced alpha interferon production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells during HIV-1 infection. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2:138-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Foster, G. R., and N. B. Finter. 1998. Are all type I human interferons equivalent? J. Viral Hepat. 5:143-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Francis, M. L., and M. S. Meltzer. 1993. Induction of IFN-alpha by HIV-1 in monocyte-enriched PBMC requires gp120-CD4 interaction but not virus replication. J. Immunol. 151:2208-2216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Francis, M. L., M. S. Meltzer, and H. E. Gendelman. 1992. Interferons in the persistence, pathogenesis, and treatment of HIV infection. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 8:199-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frese, M., G. Kochs, H. Feldmann, C. Hertkorn, and O. Haller. 1996. Inhibition of bunyaviruses, phleboviruses, and hantaviruses by human MxA protein. J. Virol. 70:915-923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frissen, P. H., F. de Wolf, P. Reiss, P. J. Bakker, C. H. Veenhof, S. A. Danner, J. Goudsmit, and J. M. Lange. 1997. High-dose interferon-alpha2a exerts potent activity against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 not associated with antitumor activity in subjects with Kaposi's sarcoma. J. Infect. Dis. 176:811-814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fuchs, D., G. M. Shearer, R. N. Boswell, D. R. Lucey, M. Clerici, G. Reibnegger, E. R. Werner, R. A. Zajac, and H. Wachter. 1991. Negative correlation between blood cell counts and serum neopterin concentration in patients with HIV-1 infection. AIDS 5:209-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gendelman, H. E., L. Baca, J. A. Turpin, D. C. Kalter, B. D. Hansen, J. M. Orenstein, R. M. Friedman, and M. S. Meltzer. 1990. Restriction of HIV replication in infected T cells and monocytes by interferon-alpha. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 6:1045-1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gendelman, H. E., L. M. Baca, J. Turpin, D. C. Kalter, B. Hansen, J. M. Orenstein, C. W. Dieffenbach, R. M. Friedman, and M. S. Meltzer. 1990. Regulation of HIV replication in infected monocytes by IFN-alpha. Mechanisms for viral restriction. J. Immunol. 145:2669-2676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gendelman, H. E., R. M. Friedman, S. Joe, L. M. Baca, J. A. Turpin, G. Dveksler, M. S. Meltzer, and C. Dieffenbach. 1990. A selective defect of interferon alpha production in human immunodeficiency virus-infected monocytes. J. Exp. Med. 172:1433-1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gessani, S., P. Puddu, B. Varano, P. Borghi, L. Conti, L. Fantuzzi, and F. Belardelli. 1994. Induction of beta interferon by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and its gp120 protein in human monocytes-macrophages: role of beta interferon in restriction of virus replication. J. Virol. 68:1983-1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Giavedoni, L. D., M. C. Velasquillo, L. M. Parodi, G. B. Hubbard, and V. L. Hodara. 2000. Cytokine expression, natural killer cell activation, and phenotypic changes in lymphoid cells from rhesus macaques during acute infection with pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 74:1648-1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goetschy, J. F., H. Zeller, J. Content, and M. A. Horisberger. 1989. Regulation of the interferon-inducible IFI-78K gene, the human equivalent of the murine Mx gene, by interferons, double-stranded RNA, certain cytokines, and viruses. J. Virol. 63:2616-2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gringeri, A., M. Musicco, P. Hermans, Z. Bentwich, M. Cusini, A. Bergamasco, E. Santagostino, A. Burny, B. Bizzini, and D. Zagury. 1999. Active anti-interferon-alpha immunization: a European-Israeli, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial in 242 HIV-1-infected patients (the EURIS Study). J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. Hum. Retrovirol. 20:358-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gutterman, J. U. 1994. Cytokine therapeutics: lessons from interferon alpha. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:1198-1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haas, D. W., J. Lavelle, J. P. Nadler, S. B. Greenberg, P. Frame, N. Mustafa, M. St. Clair, R. McKinnis, L. Dix, M. Elkins, and J. Rooney. 2000. A randomized trial of interferon alpha therapy for HIV type 1 infection. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 16:183-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haller, O., M. Frese, and G. Kochs. 1998. Mx proteins: mediators of innate resistance to RNA viruses. Rev. Sci. Tech. 17:220-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Halminen, M., J. Ilonen, I. Julkunen, O. Ruuskanen, O. Simell, and M. J. Makela. 1997. Expression of MxA protein in blood lymphocytes discriminates between viral and bacterial infections in febrile children. Pediatr. Res. 41:647-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hess, G., S. Rossol, R. Rossol, and K. H. Meyer zum Buschenfelde. 1991. Tumor necrosis factor and interferon as prognostic markers in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Infection 19:S93-S97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hirsch, V. M., T. R. Fuerst, G. Sutter, M. W. Carroll, L. C. Yang, S. Goldstein, M. Piatak, Jr., W. R. Elkins, W. G. Alvord, D. C. Montefiori, B. Moss, and J. D. Lifson. 1996. Patterns of viral replication correlate with outcome in simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected macaques: effect of prior immunization with a trivalent SIV vaccine in modified vaccinia virus Ankara. J. Virol. 70:3741-3752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Horisberger, M. A. 1995. Interferons, Mx genes, and resistance to influenza virus. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 152:S67-S71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hug, H., M. Costas, P. Staeheli, M. Aebi, and C. Weissmann. 1988. Organization of the murine Mx gene and characterization of its interferon- and virus-inducible promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8:3065-3079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jakschies, D., H. Hochkeppel, M. Horisberger, H. Deicher, and P. von Wussow. 1990. Emergence and decay of the human Mx homolog in cancer patients during and after interferon-alpha therapy. J. Biol. Response Mod. 9:305-312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jakschies, D., R. Zachoval, R. Muller, M. Manns, K. U. Nolte, H. K. Hochkeppel, M. A. Horisberger, H. Deicher, and P. Von Wussow. 1994. Strong transient expression of the type I interferon-induced MxA protein in hepatitis A but not in acute hepatitis B and C. Hepatology 19:857-865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Joag, S. V., E. B. Stephens, R. J. Adams, L. Foresman, and O. Narayan. 1994. Pathogenesis of SIVmac infection in Chinese and Indian rhesus macaques: effects of splenectomy on virus burden. Virology 200:436-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jones, G. J., C. Watera, S. Patterson, A. Rutebemberwa, P. Kaleebu, J. A. Whitworth, F. M. Gotch, and J. W. Gilmour. 2001. Comparative loss and maturation of peripheral blood dendritic cell subpopulations in African and non-African HIV-1-infected patients. AIDS 15:1657-1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kaser, A., and H. Tilg. 2001. Interferon-alpha in inflammation and immunity. Cell Mol. Biol. 47:609-617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Keir, M. E., C. A. Stoddart, V. Linquist-Stepps, M. E. Moreno, and J. M. McCune. 2002. IFN-alpha secretion by type 2 predendritic cells up-regulates MHC class I in the HIV-1-infected thymus. J. Immunol. 168:325-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Khatissian, E., M. G. Tovey, M. C. Cumont, V. Monceaux, P. Lebon, L. Montagnier, B. Hurtrel, and L. Chakrabarti. 1996. The relationship between the interferon alpha response and viral burden in primary SIV infection. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 12:1273-1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kilby, J. M. 2001. Human immunodeficiency virus pathogenesis: insights from studies of lymphoid cells and tissues. Clin. Infect. Dis. 33:873-884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Korth, M. J., M. D. Taylor, and M. G. Katze. 1998. Interferon inhibits the replication of HIV-1, SIV, and SHIV chimeric viruses by distinct mechanisms. Virology 247:265-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Koup, R. A. 2001. A new latent HIV reservoir. Nat. Med. 7:404-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kracke, A., P. von Wussow, A. N. Al-Masri, G. Dalley, A. Windhagen, and F. Heidenreich. 2000. Mx proteins in blood leukocytes for monitoring interferon beta-1b therapy in patients with MS. Neurology 54:193-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Krown, S. E., D. Niedzwiecki, R. B. Bhalla, N. Flomenberg, D. Bundow, and D. Chapman. 1991. Relationship and prognostic value of endogenous interferon-alpha, beta 2-microglobulin, and neopterin serum levels in patients with Kaposi sarcoma and AIDS. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 4:871-880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kunzi, M. S., H. Farzadegan, J. B. Margolick, D. Vlahov, and P. M. Pitha. 1995. Identification of human immunodeficiency virus primary isolates resistant to interferon-alpha and correlation of prevalence to disease progression. J. Infect. Dis. 171:822-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lane, H. C., V. Davey, J. A. Kovacs, J. Feinberg, J. A. Metcalf, B. Herpin, R. Walker, L. Deyton, R. T. Davey, Jr., J. Falloon, et al. 1990. Interferon-alpha in patients with asymptomatic human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 112:805-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Langford, M. P., D. H. Wyrick, J. P. Ganley, G. B. Baskin, M. Murphey-Corb, K. F. Soike, and L. N. Martin. 1996. Temporal association of interferon-alpha and p27 core antigen levels in sera of simian immunodeficiency virus infected monkeys. Microb. Pathog. 20:171-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lau, A. S., S. E. Read, and B. R. Williams. 1988. Downregulation of interferon alpha but not gamma receptor expression in vivo in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J. Clin. Investig. 82:1415-1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Letvin, N. L., J. E. Schmitz, H. L. Jordan, A. Seth, V. M. Hirsch, K. A. Reimann, and M. J. Kuroda. 1999. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes specific for the simian immunodeficiency virus. Immunol. Rev. 170:127-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lindenmann, J., C. A. Lane, and D. Hobson. 1963. The resistance of A2G mice to myxoviruses. J. Immunol. 90:942-951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu, Y. J., N. Kadowaki, M. C. Rissoan, and V. Soumelis. 2000. T cell activation and polarization by DC1 and DC2. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 251:149-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lu, X., H. Kiyono, D. Lu, S. Kawabata, J. Torten, S. Srinivasan, P. J. Dailey, J. R. McGhee, T. Lehner, and C. J. Miller. 1998. Targeted lymph-node immunization with whole inactivated simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) or envelope and core subunit antigen vaccines does not reliably protect rhesus macaques from vaginal challenge with SIVmac251. AIDS 12:1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Luft, T., K. C. Pang, E. Thomas, P. Hertzog, D. N. Hart, J. Trapani, and J. Cebon. 1998. Type I IFNs enhance the terminal differentiation of dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 161:1947-1953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Matheux, F., E. Lauret, V. Rousseau, J. Larghero, B. Boson, B. Vaslin, A. Cheret, E. De Maeyer, D. Dormont, and R. LeGrand. 2000. Simian immunodeficiency virus resistance of macaques infused with interferon beta-engineered lymphocytes. J. Gen. Virol. 81:2741-2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Meier, V., S. Mihm, and G. Ramadori. 2000. MxA gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients infected chronically with hepatitis C virus treated with interferon-alpha. J. Med. Virol. 62:318-326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Miller, C. J., N. J. Alexander, S. Sutjipto, S. M. Joye, A. G. Hendrickx, M. Jennings, and P. A. Marx. 1990. Effect of virus dose and nonoxynol-9 on the genital transmission of SIV in rhesus macaques. J. Med. Primatol. 19:401-409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Miller, C. J., M. Marthas, J. Torten, N. J. Alexander, J. P. Moore, G. F. Doncel, and A. G. Hendrickx. 1994. Intravaginal inoculation of rhesus macaques with cell-free simian immunodeficiency virus results in persistent or transient viremia. J. Virol. 68:6391-6400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Muller, U., U. Steinhoff, L. F. Reis, S. Hemmi, J. Pavlovic, R. M. Zinkernagel, and M. Aguet. 1994. Functional role of type I and type II interferons in antiviral defense. Science 264:1918-1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nokta, M., J. P. Loh, S. M. Douidar, A. E. Ahmed, and R. B. Pollard. 1991. Metabolic interaction of recombinant interferon-beta and zidovudine in AIDS patients. J. Interferon Res. 11:159-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Oka, S., Y. Hirabayashi, H. Mouri, S. Sakurada, H. Goto, K. Ohnishi, S. Kimura, K. Mitamura, and K. Shimada. 1989. Beta-interferon and early stage HIV infection. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2:125-128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Oka, S., K. Urayama, Y. Hirabayashi, S. Kimura, K. Mitamura, and K. Shimada. 1992. Human immunodeficiency virus DNA copies as a virologic marker in a clinical trial with beta-interferon. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 5:707-711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pacanowski, J., S. Kahi, M. Baillet, P. Lebon, C. Deveau, C. Goujard, L. Meyer, E. Oksenhendler, M. Sinet, and A. Hosmalin. 2001. Reduced blood CD123+ (lymphoid) and CD11c+ (myeloid) dendritic cell numbers in primary HIV-1 infection. Blood 98:3016-3021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pantaleo, G., C. Graziosi, L. Butini, P. A. Pizzo, S. M. Schnittman, D. P. Kotler, and A. S. Fauci. 1991. Lymphoid organs function as major reservoirs for human immunodeficiency virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:9838-9842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pantaleo, G., C. Graziosi, J. F. Demarest, L. Butini, M. Montroni, C. H. Fox, J. M. Orenstein, D. P. Kotler, and A. S. Fauci. 1993. HIV infection is active and progressive in lymphoid tissue during the clinically latent stage of disease. Nature 362:355-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Platanias, L. C., S. Uddin, P. Domanski, and O. R. Colamonici. 1996. Differences in interferon alpha and beta signaling. Interferon beta selectively induces the interaction of the alpha and betaL subunits of the type I interferon receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 271:23630-23633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Poli, G., P. Biswas, and A. S. Fauci. 1994. Interferons in the pathogenesis and treatment of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Antivir. Res. 24:221-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pomerantz, R. J., and M. S. Hirsch. 1987. Interferon and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Interferon 9:113-127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Popik, W., and P. M. Pitha. 1992. Transcriptional activation of the tat-defective human immunodeficiency virus type-1 provirus: effect of interferon. Virology 189:435-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]