Abstract

Walleye dermal sarcoma virus (WDSV) encodes an accessory protein, OrfA, with sequence homology to cyclins (retrovirus cyclin). In cells transfected with an expression construct, OrfA was localized to the nucleus and was concentrated in interchromatin granule clusters (IGCs), sites where splicing factors are concentrated. Other proteins identified in IGCs include transcription factors, the large subunit of RNA polymerase II (Pol II), and cyclin-dependent kinase 8 (cdk8). cdk8 is the kinase partner of cyclin C and a component of the mediator complex, associated with the Pol II holoenzyme. cdk8 and cyclin C can regulate transcription via phosphorylation of cyclin H and the carboxy-terminal domain of Pol II. OrfA in transfected HeLa cells was found to colocalize and copurify with hyperphosphorylated forms of Pol II (Pol IIO) in IGCs, and OrfA was coimmunoprecipitated from lysates of transfected cells with an antibody against Pol IIO. Likewise, Pol IIO could be coprecipitated with an antibody against OrfA. A survey with antibodies against several different cdks resulted in coimmunoprecipitation of OrfA with anti-cdk8, and antiserum against OrfA was able to coprecipitate cdk8 from lysates of cells that express OrfA. Coprecipitation of OrfA with anti-cyclin C demonstrated that it was included in complexes with OrfA and cdk8. OrfA has sequence and structural similarities to cyclin C, and, functionally, OrfA appears to have the capacity to both enhance and inhibit the activity of promoters in a cell-specific manner, similar to functions of the mediator complex. These data suggest that WDSV OrfA functions through its interactions with these large, transcription complexes. Further investigations will clarify the role of the retrovirus cyclin in control of virus expression and transformation.

Walleye dermal sarcoma virus (WDSV) is a member of the newly defined genus Epsilonretrovirus, of the family Retroviridae. WDSV is a complex retrovirus that is etiologically associated with dermal sarcomas in walleye fish (Stizostedion vitreum) (28, 29, 41, 45, 46). Rapid onset and high efficiency characterize the experimental transmission of this disease (7). Dermal sarcomas develop and regress seasonally, and the shift to regression is associated with qualitative and quantitative differences in viral gene expression: developing tumors contain low levels of two subgenomic transcripts, and regressing tumors contain approximately 1,000-fold-greater levels of full-length viral RNA, a variety of spliced transcripts, and unintegrated viral DNA (6, 7, 37).

WDSV contains three large open reading frames in addition to the gag, pol, and env genes, orfa and orfb, located in the 3′-proximal region of the genome, and orfc, located between the 5′ long terminal repeat (LTR) and gag (18). The OrfA protein of WDSV and homologous proteins, encoded by walleye epidermal hyperplasia virus type 1 (WEHV-1) and WEHV-2, have limited homology to cyclins and are referred to as retrovirus cyclins (23). Viral oncogenes transduced by retroviruses demonstrate significant homology to their cellular counterparts, whereas the retrovirus cyclins have divergent homology, which is limited to the cyclin box motif (19% identity and 29% similarity to human D cyclin and 17% identity and 30% similarity to walleye D cyclin [23]). The retrovirus cyclin from WDSV, but not that from WEHV-1 or WEHV-2, was able to induce cell cycle progression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae that are deficient in G1 cyclins (23). The WDSV cyclin was also associated with hyperplastic skin lesions in transgenic mice (22).

Transcripts that encode OrfA result from a pattern of alternative splice site selection similar to that for other complex retroviruses. Six such alternate transcripts, A1 to A6, can encode variant forms of the protein. Only A1 contains the entire orfa reading frame. During tumor development, only transcript A1 and a transcript containing orfb can be detected by Northern analysis (37, 38). The OrfA protein, expressed in cell culture, can inhibit the activity of the WDSV promoter (47), and it is localized in the nucleus in interchromatin granule clusters (IGCs) (38). IGCs contain a variety of proteins that are necessary for transcription and mRNA processing. These include splicing factors, several transcription factors, the large subunit of RNA polymerase II (Pol II), and cyclin-dependent kinase 8 (cdk8; the kinase partner of cyclin C) (5, 9, 20, 26, 33, 39).

The previous localization of the OrfA protein with components of transcription and splicing machinery suggested that it has a functional role in these processes, and there is certainly a precedent for control of retrovirus expression by an accessory protein at the level of transcription or mRNA processing. With an in vitro system, wherein exogenous viral protein OrfA was expressed with a hemagglutinin (HA) epitope tag, we first examined the association of OrfA and Pol II by colocalization, copurification, and coimmunoprecipitation and proceeded to identify a cdk that is associated with the WDSV cyclin. We further demonstrate that OrfA can function to either inhibit or activate transcription in a manner dependent on both the promoter and the cell.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and expressed proteins.

Immortalized mammalian cell lines Cf2Th (canine thymus, ATCC CRL 1430) (35), HeLa (human carcinoma, ATCC CCL 2) (14), and NIH 3T3 (mouse fibroblast, ATCC CRL 1658) (2, 12, 19) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium with 5% bovine serum at 37°C with 5% CO2. Immortalized WF-2 walleye fry fibroblasts and primary W12 fibroblasts were maintained in HEPES-buffered minimum essential medium (pH 7.4) with Hanks salts and 10% fetal bovine serum at 20°C. WF-2 cells were derived from whole walleye fry in the laboratory of Bruce Calnek, Cornell University (44). W12 cells were derived from walleye dermal sarcomas in the laboratory of Paul Bowser, Cornell University. They do not harbor WDSV provirus (38).

WDSV orfa, orfb, and the coding sequences for OrfA deletion mutants OrfA-NH3− and OrfA-COOH− were cloned in the pKH3 vector (a generous gift from Jun-Lin Guan, Cornell University) as previously described (10, 30, 38). This vector fuses three influenza virus HA tags on the amino terminus of the expressed protein. OrfA-NH3− starts at the methionine at position 113 of the OrfA amino acid sequence (18). OrfA-COOH− ends at position 220 of the OrfA sequence. Cells were transfected by using FuGENE6 (Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cf2Th stable transfectants expressing WDSV OrfA, clone Cf2Th-OrfA, were produced by cotransfection of pKH3OrfA and a plasmid encoding neomycin resistance, pMC1neo (Stratagene). Cells were selected with G-418, and single colonies of cells were expanded and assayed for OrfA expression by immunofluorescence with antiserum reactive to OrfA (38). Clone Cf2Th-OrfA was further single-cell cloned by dilution. FLAG and HA epitope-tagged human cdk8 (hSRB10) was expressed from a full-length cDNA clone in pCIN4 vector pCIN4CDK8 (16) (a generous gift from Robert G. Roeder, The Rockefeller University).

Reporter-gene constructs and assays.

The WDSV LTR was amplified by PCR from clone pWDSV1.05 (28) with a T3 primer and LTRQ1 (GAAGATCTGTTAATTCAAATTCACTTATCT). The amplified product was digested with XbaI and BglII and ligated into digested vector pBLCAT3 (27). The LTR was excised from pBLCAT3 by digestion with XbaI and BglII and subcloned into the NheI and BglII sites in vector pGL3-Basic (Promega). The U3 region of the WDSV LTR was amplified from a full-length WDSV plasmid clone, pDL1 (22) by using 5′ and 3′ primers that incorporate NheI and BglII restriction sites (GCTAGCTGAGAAACTAATTTTTGTT and GAAGATCTGAGACCCCGTTCTT). The amplified product was digested with NheI and BglII and ligated into pGL3-Basic.

NIH 3T3, HeLa, or W12 cells were seeded into 24-well plates in a volume of 1 ml of complete medium. Cells were transfected with 0.2 μg of a luciferase reporter vector (pGL3-LTR, pGL3-U3, or pGL3-Control; Promega), 0.05 μg of pKH3OrfA or pCMV-Ha (Clontech), and 0.005 μg of pRL-TK (Promega) by using FuGENE6 (Roche). pGL3-Control contains the simian virus 40 (SV40) promoter and enhancer sequences. Experiments were performed using the dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega), which sequentially measures firefly and Renilla luciferase activities from a single sample. Cell lysates were harvested 48 or 72 h after transfection with passive lysis buffer and then centrifuged at 21,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Luciferase activities were determined according to manufacturer's instruction by using a TD-20/20 luminometer (Turner Designs). Luciferase activity from the reporter vector was normalized for transfection efficiency by using values obtained from the cotransfected pRL-TK vector. All transfections were performed in triplicate, and the results are presented as the means ± standard deviations. Student's t test and 95% confidence intervals based on a t distribution were used for statistical analyses. A P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Isolation of IGCs.

IGCs were purified as previously described (32) with minor modifications for HeLa cells. Cells were lysed in 0.5% Nonidet P-40 (NP-40) in phosphate-buffered saline, and the nuclei were centrifuged at 21,000 × g for 5 s and washed in 0.1% NP-40. Nuclear isolation of greater than 90% was confirmed microscopically. Isolated nuclei were then extracted with 1% Triton X-100 in TM5 buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 2 μg of leupeptin and aprotinin/ml, 1 μg of pepstatin/ml, 0.2 mM sodium orthovanadate) and processed as previously described. Briefly, extracted nuclei were digested with RNase-free DNase I, and the digested chromatin was removed by three extractions with 0.5 M NaCl in TM5 buffer. The remaining material, in 0.5 M NaCl-TM5 supplemented with 5 mM dithiothreitol, was sheared by passage through a 27-gauge needle and homogenized in a Dounce homogenizer. One volume of the homogenized material was added to 5 volumes of 0.25 M Cs2SO4 in TM5 buffer, and the mixture was centrifuged for 2 min at 20,800 × g. The supernatant was supplemented with 2 volumes of TM5 buffer and centrifuged for 1 h at 157,000 × g to pellet the IGCs. IGCs were suspended in TM5 buffer, and an aliquot was extracted with 1 M potassium iodide in order to quantitate protein content. Twenty-microgram equivalents of the IGC suspensions and 15 μg of either NP-40 lysate or Triton X-100 nuclear extract (NE) were analyzed on 3 to 8% denaturing polyacrylamide gels. Separated proteins were transferred to an Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore) and incubated with a primary antibody overnight at 4°C. Blots were washed, incubated with affinity-purified rabbit anti-goat immunoglobulin G (IgG), goat anti-rabbit IgG, or goat anti-mouse IgG antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Kirkegaard and Perry Laboratories), and developed with 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine substrate (Kirkegaard and Perry Laboratories). Antibody complexes were removed from blots by incubation for 1 h at 50°C in Western strip buffer (62 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 100 mM β-mercaptoethanol). Blots were probed successively with three monoclonal antibodies reactive to the RNA Pol II carboxy-terminal domain (CTD), clones 8WG16, H14, and H5 (Covance), with goat anti-cdk8 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and with an anti-HA antibody (clone 12CA5; Roche). Goat anti-SF2/ASF (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used to confirm enrichment of IGCs (32). Antibody clone H5 detects phosphorylated serine 2 (underlined) of heptad repeat YSPTSPS (9, 20). Antibody clone H14 is specific for phosphoserine 5 (underlined) in YSPTSPS.

Immunoprecipitation.

Cells were lysed at 48 h posttransfection with IP buffer (1% Triton X-100, 0.5% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], 1 mM EGTA, 2 μg of leupeptin and aprotinin/ml, 1 μg of pepstatin/ml, 0.2 mM sodium orthovanadate, 0.2 mM PMSF). Lysates were centrifuged at 21,000 × g for 30 min, and the protein concentration of the supernatants was determined by a micro-bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce). Cell lysates (1 mg of total protein) were diluted to a concentration of 1 μg/μl in IP buffer and precleared for 2 h with 50 μl of a suspension of protein G-Sepharose (Pharmacia Biotech). Antibodies (1 to 5 μg) were added to 250-μl aliquots (250 μg equivalent) of precleared lysates; the aliquots were incubated for 1 h prior to the addition of 50 μl of a protein G suspension and then rotated overnight at 4°C. Protein G pellets were washed four times with IP buffer and suspended in 30 μl of loading buffer, and the suspension was heated for 10 min at 70°C. Fifteen-microliter aliquots were separated under denaturing conditions in a 4 to 12% polyacrylamide gel. Cell lysates (15 μg of protein) were loaded in control lanes. Western blotting was performed as described above. The antibodies used for immunoprecipitation and Western blotting included mouse monoclonal antibodies reactive to the HA epitope (clone 12CA5; Roche) and the FLAG epitope (clone M2; Upstate Biotechnology); mouse monoclonal anti-cyclin B and anti-cyclin A (Transduction Laboratories), anti-cyclin D1 (Pharmingen), anti-cdk7 and anti-SC35 (Sigma); rabbit polyclonal anti-HA (HA.11; Covance), anti-cdc2 (cdk1), anti-cdk2, and anti-cdk4 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-cyclin H (Sigma), and anti-cyclin C (Oncogene Research Products); and goat polyclonal anti-SF2/ASF, anti-cdk8, anti-cdk9, anti-cyclin C, and anti-cyclin T1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Rabbit antisera reactive to WDSV OrfA and Orf C proteins were prepared as previously described, affinity purified, and adsorbed with cultured cells (38).

In addition to whole-cell lysates prepared with IP buffer, immunoprecipitations were performed with cell extracts, cytosolic and nuclear, prepared by hypotonic lysis and 420 mM KCl extraction of nuclei as described by Mayeda and Krainer (31). This protocol is a modification of that described by Dignam et al. (13) for the preparation of components for in vitro splicing and transcription reactions. Immunoprecipitation from these preparations was performed in buffer D (20 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 8.0], 100 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 20% glycerol, 0.5 mM PMSF, 1 mM dithiothreitol), but the resulting protein G-Sepharose pellets were washed in IP buffer as described above.

Analysis of protein sequences.

All protein sequences were obtained from GenBank and aligned with Vector NTI 5.3.0 multiple-sequence-alignment software (Informax Inc.) by using the Clustal W algorithm (40). Predicted secondary structures were prepared by submission of individual sequences to Network Protein Sequence Analysis at http://npsa-pbil.ibcp.fr to derive a consensus structure from eight separate methods of secondary-structure prediction (11). Identification of putative coiled coils and predictions of dimer and trimer formation were made by submission of cyclin and OrfA protein sequences to the Paircoil and Multicoil programs (4, 43) at http://nightingale.lcs.mit.edu.

RESULTS

OrfA copurifies with RNA Pol II in IGCs.

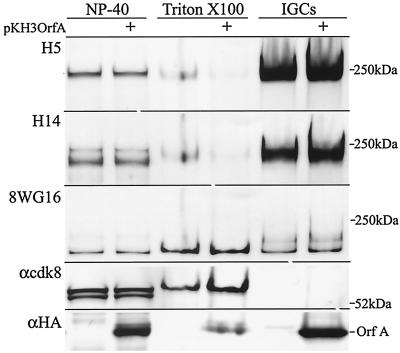

Previously, immunofluorescence assays demonstrated the colocalization of OrfA with SC35, a splicing factor concentrated in IGCs (38). Hyperphosphorylated Pol II (Pol IIO), NF-κB, and cdk8 have also been localized in these nuclear structures (9). To determine whether OrfA and RNA Pol II colocalize in IGCs, an antibody to Pol IIO, clone H5, and anti-OrfA antiserum were used to demonstrate overlapping localization of these two proteins in IGCs of cells transfected with OrfA expression vector pKH3OrfA (data not shown). HeLa cells transfected with either the control vector, pKH3, or pKH3OrfA were then subjected to fractionation and further analysis. Isolated nuclei were extracted with Triton X-100, and IGCs were prepared from these nuclei by extensive DNase digestion and 0.5 M NaCl extraction, followed by homogenization and differential precipitation of the nuclear matrix fraction in Cs2SO4 (32). These extracts were analyzed by Western blotting (Fig. 1). HA-tagged OrfA was present in all fractions from cells transfected with the pKH3OrfA vector. OrfA was concentrated in the IGCs, and low levels were found in the nuclear fraction solubilized in 1% Triton X-100. There were significant amounts in the initial NP-40 lysate, but a variety of nuclear proteins were identified in this fraction. The suspension of purified IGCs was greatly enriched with Pol IIO, detected by antibody clones H5 and H14. These forms of Pol IIO were present at relatively low levels in the Triton X-100-soluble NE, and levels were lower in cells expressing OrfA. The Triton X-100-soluble NE contained the highest levels of unphosphorylated Pol II (Pol IIA) as detected with antibody clone 8WG16 (9), and levels of this form for control and OrfA transfectants were comparable.

FIG. 1.

Western analysis of NP-40 lysates, Triton X-100 NEs, and IGC preparations from control pKH3- and pKH3OrfA-transfected HeLa cells. Soluble protein preparations (15 μg) and a quantity of each IGC suspension equivalent to 20 μg of KI-soluble protein were run on a 3 to 8% polyacrylamide gel under denaturing conditions. The blot was probed successively for unphosphorylated Pol II CTD (8WG16), CTD phosphoserine 2 (H5), CTD phosphoserine 5 (H14), cdk8, and OrfA (anti-HA). The sizes and positions of the nearest molecular mass markers are indicated. The HA-tagged OrfA protein runs at approximately 37 kDa.

The IGC fraction did not contain cdk8. Two bands with approximate molecular masses of 53 and 55 kDa were present in the NP-40 lysate. These bands correspond to the different sizes of cdk8 observed previously (42). The Triton X-100-soluble extract from nuclei contained only the higher-molecular-weight form. The larger of the two forms of cdk8 has been observed in complexes of approximately 2 MDa that can stimulate activated transcription in vitro, and the smaller of the two forms is associated with a complex of approximately 150 kDa that inhibits activated transcription (42).

OrfA is coimmunoprecipitated with Pol IIO.

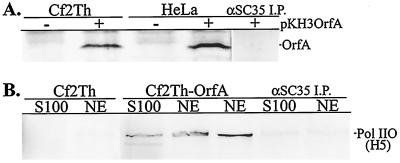

To further analyze the physical association between OrfA and Pol II, total-cell extracts were prepared from transiently transfected HeLa and Cf2Th cells. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with antibody clone H5, and the precipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA to detect HA-tagged OrfA. OrfA was coimmunoprecipitated with Pol IIO from all cells expressing OrfA but was not coprecipitated with the monoclonal antibody reactive to SC35 (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

(A) Coimmunoprecipitation of OrfA with anti-Pol IIO-specific monoclonal antibody H5 from lysates of transient, pKH3OrfA-transfected Cf2Th and HeLa cells. OrfA was detected with anti-HA antibody 12CA5. The last lane shows anti-SC35 immunoprecipitate (I.P.) from OrfA-transfected HeLa cells. (B) Coimmunoprecipitation of Pol IIO with an anti-HA antibody from S100 and NEs of OrfA-expressing clone Cf2Th-OrfA cells. Pol IIO was detected with the H5 monoclonal antibody. The last two lanes show the anti-SC35 immunoprecipitate from S100 and NE preparations of Cf2Th-OrfA cells.

The reciprocal experiment, coprecipitation of Pol IIO with the anti-HA antibody, was not successful with whole-cell lysates from transiently transfected cells. OrfA in these cells was greatly overexpressed from the pKH3OrfA vector, and even excess anti-HA antibody or anti-OrfA serum could precipitate only a fraction of the OrfA in these lysates (not shown). Therefore, Cf2Th cell clone Cf2Th-OrfA, which stably expresses OrfA from pKH3OrfA, was derived. These cells uniformly express moderate levels of OrfA, as determined by immunofluorescence and Western blotting (not shown). Further, S100 and NEs were prepared from these cells in order to enrich for OrfA located in the nuclei of these cells. The cytosolic S100 is the soluble fraction from hypotonic cell lysis and contains many soluble nuclear components (31). The NE is a 0.42 M KCl extract of nuclei that supports splicing and transcription reactions in vitro (31). Pol IIO was coimmunoprecipitated from both of these preparations with the anti-HA antibody only from the Cf2Th-OrfA cells (Fig. 2B). A control monoclonal antibody reactive to splicing factor SC35 did not precipitate significant quantities of Pol IIO (Fig. 2B).

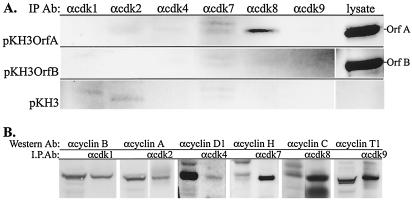

OrfA is present in cdk8 immunoprecipitates.

A survey of cdks (cdk1, -2, -4, -7, -8, and -9) that might interact with OrfA, the retrovirus cyclin, was performed by coimmunoprecipitation with a collection of anti-cdk antibodies. Total-cell lysates of HeLa cells transfected with the control vector or vectors expressing HA-OrfA (pKH3OrfA) or HA-OrfB (pKH3OrfB) were used. Only the antibody specific for cdk8 was able to coprecipitate OrfA, as detected on Western blots of the immunoprecipitate with anti-HA (Fig. 3A). There was no precipitation of HA-tagged OrfB with any of the antibodies. The antibodies against cdk1, -2, -4, -7, -8, and -9 were able to coimmunoprecipitate their cyclin partners, cyclins B, A, D1, H, C, and T, respectively, from these lysates (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

(A) Coimmunoprecipitations with a panel of antisera and monoclonal antibodies reactive to different cdks on lysates of transiently transfected HeLa cells. Cells were transfected with pKH3OrfA (top), pKH3OrfB (middle), or control pKH3 vector (bottom). Each lane contains the immunoprecipitate from the indicated antibody (IP Ab). The expressed, HA-tagged proteins were detected with anti-HA antibody 12CA5. Samples of the cell lysates for immunoprecipitations appear in the last lane (20 μg of total protein). HA-tagged proteins OrfA and OrfB run at approximately 37 and 39 kDa, respectively. (B) Control coimmunoprecipitations with antibodies used in panel A. The anti-cyclin antibody used as the probe is indicated (Western Ab), and each section contains a lane with the lysate used for immunoprecipitation (15 μg of total protein) and a lane with the indicated immunoprecipitate (I.P.Ab). The apparent molecular masses of individual cyclins were as follows: cyclin B, 62 kDa; cyclin A, 60 kDa, cyclin D1, 36 kDa; cyclin H, 36 kDa; cyclin C, 31 kDa; cyclin T1, 89 kDa.

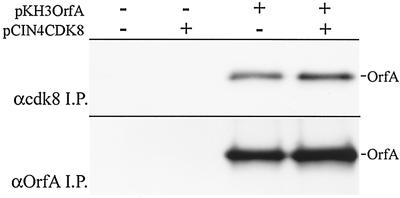

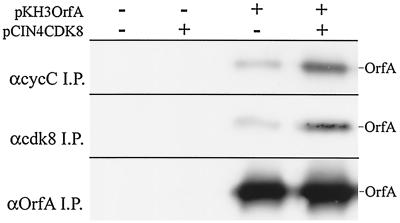

To repeat the coprecipitation of OrfA in a piscine cell line with available anti-human cdk8 antibodies, pKH3OrfA was cotransfected with human cdk8 expression vector pCIN4CDK8 containing the coding sequences for the FLAG and HA tags (16) in the walleye fry cell line, WF2. The antibody to human cdk8 was able to coprecipitate OrfA with or without coexpression of human cdk8 (Fig. 4), indicating both the interaction of walleye cdk8 with OrfA and the cross-reactivity of the human antibody for walleye cdk8.

FIG. 4.

(Top) Coimmunoprecipitations of expressed OrfA from lysates of walleye cells (WF-2 cells) with anti-human cdk8. Cells were transfected or cotransfected with pKH3OrfA and/or pCIN4CDK8 (FLAG- and HA-tagged human cdk8) as indicated. (Bottom) Control immunoprecipitations (I.P.) of OrfA with anti-OrfA antiserum. OrfA was detected with anti-HA monoclonal antibody 12CA5.

In reciprocal experiments with OrfA-transfected HeLa cells and Cf2Th-OrfA cells, there was no detectable cdk8 in anti-OrfA or anti-HA immunoprecipitates from whole-cell lysates. However, anti-OrfA serum was able to precipitate two proteins, reactive with anti-cdk8, from NEs of OrfA-transfected HeLa cells. These proteins were approximately 53 and 55 kDa and either were immunoprecipitated with anti-cyclin C and anti-cdk8 or were present in the nuclear extract (Fig. 5A). The protein with an apparent molecular mass of 53 kDa, near the value predicted for cdk8 (53.3 kDa), was most abundant in the anti-cyclin C and anti-cdk8 precipitates, but it was present at low levels in anti-OrfA precipitates. The larger protein was more clearly distinguished in the NE and in anti-OrfA precipitates and may correspond to a posttranslational modification of cdk8, possibly by phosphorylation (42) (Fig. 1). These results suggested the association of OrfA with the larger form of cdk8. These bands were not visible in anti-OrfA immunoprecipitates of nuclear extracts from control transfectants and were not visible in immunoprecipitates of NEs of OrfA transfectants when irrelevant polyclonal rabbit antiserum was used (Fig. 5A).

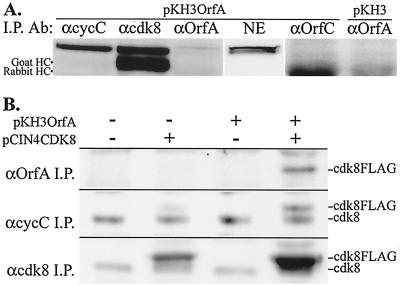

FIG. 5.

(A) Coimmunoprecipitation of cdk8 from NEs of HeLa cells transfected with pKH3OrfA. Antisera used for immunoprecipitations (I.P. Ab) included rabbit anti-cyclin C, goat anti-cdk8, rabbit anti-OrfA, and rabbit anti-WDSV OrfC. Cdk8 was detected on Western blots with goat anti-cdk8 and an anti-goat IgG secondary antibody. The heavy chains (HC) of precipitating goat and rabbit IgGs are indicated. NE (15 μg) is in the fourth lane from the left, and the right lane contains anti-OrfA immunoprecipitate from the NE of control, pKH3-transfected cells. (B) Coimmunoprecipitation of endogenous and/or FLAG- and HA-tagged cdk8 from whole-cell lysates of HeLa cells. Cells were transfected or cotransfected with pKH3OrfA and pCIN4CDK8 (FLAG- and HA-tagged human cdk8) as indicated. Immunoprecipitation antisera, anti-OrfA, anti-cyclin C, and anti-cdk8, are indicated. cdk8 was detected with goat anti-cdk8 antiserum, and the positions of endogenous and epitope-tagged cdk8 protein bands are indicated (cdk8 and cdk8FLAG, respectively).

Confirmation of the association between OrfA and cdk8 was performed by coexpression of FLAG- and HA-tagged cdk8 with OrfA and the coimmunoprecipitation of this exogenous cdk8 with anti-OrfA sera directly from whole-cell lysates (Fig. 5B). Besides having a distinctive size, the exogenous cdk8 was present at higher levels than those of OrfA and was, therefore, likely to be included in the portion of OrfA captured by immunoprecipitation. Antibodies against cyclin C and cdk8 coprecipitated both the endogenous and exogenous forms of the cdk8 protein (Fig. 5B). These results clearly identified the tagged cdk8 and native forms and demonstrated the association of the exogenous cdk8 in complexes with endogenous cyclin C. An anti-FLAG antibody was also able to immunoprecipitate the FLAG-tagged cdk8, and these immunoprecipitates included OrfA from dually transfected cells (not shown), further demonstrating the association of cdk8 and OrfA with a second, unrelated antibody.

Cyclin C is included in OrfA-cdk8 immune complexes.

The association of cyclin C with complexes containing cdk8 and OrfA was also examined by coimmunoprecipitation. OrfA was coprecipitated with anti-cyclin C from whole-cell lysates of transfected cells (Fig. 6). This suggests that OrfA does not displace cyclin C from complexes with cdk8. Additionally, the coexpression of exogenous cdk8 with OrfA enhanced the coprecipitation of OrfA with both the cyclin C and the cdk8 antibodies (Fig. 6). Not only is the tagged cdk8 associated with cyclin C and with OrfA, as seen in Fig. 5B, but also the excess cdk8 is able to associate with more OrfA and to bring more OrfA into complexes with cyclin C. This result suggests that cdk8 is the limiting factor in the association of cyclin C and OrfA and further supports the proposal that OrfA does not displace cyclin C from cdk8 pairings in spite of its cyclin homology.

FIG. 6.

(Top) Coimmunoprecipitations of OrfA from lysates of HeLa cells with anti-cyclin C antiserum. Cells were transfected or cotransfected with pKH3OrfA and pCIN4CDK8 (FLAG- and HA-tagged human cdk8) as indicated. (Middle) Immunoprecipitations (I.P.) of expressed OrfA with anti-cdk8 antiserum. (Bottom) control immunoprecipitations with anti-OrfA antiserum. OrfA was detected with anti-HA monoclonal antibody 12CA5.

Protein sequence and structural comparisons.

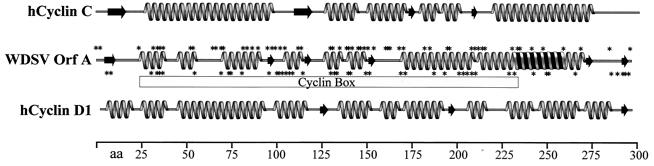

The sequences of cdk8 and cyclin C are highly conserved among metazoan organisms. For instance, the sequences of human and Drosophila melanogaster cdk8 proteins are 82% identical and 88% similar and those of human and Drosophila cyclin C proteins are 72% identical and 84% similar. Alignment of the protein sequences of WDSV OrfA with human cyclins showed that OrfA and cyclin D1 are 15% identical and 25% similar over their entire lengths and that OrfA and cyclin C are 20% identical and 30% similar. Human homologues were arbitrarily chosen for these analyses, because piscine cyclin C sequences are not yet available and because it has been shown that OrfA is as related to human D cyclins as it is to walleye D cyclins (23). Predicted secondary structures of OrfA and human cyclins C and D1 were prepared with the Network Protein Sequence Analysis (11). This program incorporates eight predicted secondary structures, from a collection of eight different algorithms, into a consensus structure. A linear representation of these structures is shown in Fig. 7. All three are dominated by the α-helices that characterize the cyclin box motif, and these regions contain the highest density of identical and similar amino acids. The comparison of these predicted structures illustrates the similarities between OrfA and both cyclins. A striking distinction between OrfA and both cyclin D and cyclin C is a predicted coiled coil in its carboxy-terminal region (Fig. 7) (4). This motif is predicted to mediate the formation of OrfA dimers or trimers as well as the possible involvement of OrfA in heterodimers (43).

FIG. 7.

Predicted secondary protein structures were compiled in consensus structures for human (h) cyclins C and D1 and WDSV OrfA. The structural elements are depicted as follows: broad arrows, β sheets; straight lines, random coils; coils, α-helices. Helices filled with black, predicted coiled coils. Asterisks above OrfA model, locations of amino acids (aa) that are identical to residues in cyclin C; asterisks below OrfA model, locations of residues identical to residues in cyclin D1. Cyclin box, region with cyclin homology.

OrfA affects promoter activity.

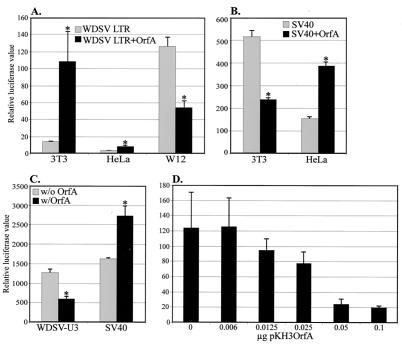

To assess the effect of OrfA on transcription from the WDSV promoter, a luciferase reporter vector with the entire WDSV LTR (pGL3-WDSVLTR) was prepared and transient transfection experiments were conducted with different cell lines. Low levels of luciferase activity from the WDSV LTR were detected in NIH 3T3 and HeLa cells (Fig. 8A). However, when the WDSV LTR was cotransfected with pKH3OrfA, luciferase activity was significantly increased in NIH 3T3 cells (7.6-fold; P < 0.02) and HeLa cells (2.9-fold; P < 0.01) (Fig. 8A). This increase in activity was repeated in three additional, independent experiments (data not shown). In contrast, the basal activity from the WDSV LTR in walleye cell line W12 was high, and OrfA inhibited this activity 2.3-fold (P < 0.0005) (Fig. 8A). A luciferase reporter construct with the SV40 promoter and enhancer was used as a control for luciferase activity in NIH 3T3, HeLa, and W12 cells. Interestingly, OrfA suppressed SV40 promoter activity 2.2-fold in NIH 3T3 cells (P < 0.002) (Fig. 8B) but increased SV40 activity 2.5-fold in HeLa cells (P < 0.0003) and 1.7-fold in W12 cells (P < 0.01) (Fig. 8B and C). Thus, OrfA was found to both enhance and inhibit transcription from the same promoters in different cell types and to enhance and inhibit different promoters in the same cell type. That is, the action of OrfA is dependent on a combination of promoter sequence and cell type.

FIG. 8.

Effects of WDSV OrfA on transcription. (A) Activity of the WDSV LTR in NIH 3T3, HeLa, and W12 cells with or without WDSV OrfA. The WDSV LTR luciferase reporter (pGL3-LTR) was cotransfected with pKH3OrfA or a control vector. Relative luciferase values are corrected for transfection efficiency with TK promoter-Renilla vector pRL-TK. (B) Effect of WDSV OrfA on an SV40 promoter-enhancer-driven luciferase reporter plasmid (pGL3-Control) in NIH 3T3 and HeLa cells. (C) Effect of WDSV OrfA on the WDSV core promoter (WDSV-U3 region, pGL3-U3) and SV40 (pGL3-Control) activity in W12 cells. (D) Titration of pKH3OrfA expression plasmid with constant WDSV-U3 reporter plasmid in W12 cells. All transfections were performed and assayed in triplicate. ∗, statistically significant value (P < 0.05).

To define the region of the WDSV LTR responsible for the effects of OrfA, a WDSV promoter construct (pGL3-WDSV-U3) containing only the core promoter (U3) region was prepared. The amount of luciferase activity from W12 cells cotransfected with WDSV-U3 and pKH3OrfA was 2.2-fold less than that from cells transfected with WDSV-U3 alone (P < 0.0007) (Fig. 8C), comparable to the inhibition of the WDSV LTR. This result indicates that the effect of OrfA on transcription from the WDSV promoter is not dependent on sequences in the R or U5 regions of the LTR. Titration of the OrfA expression vector in cotransfection assays with WDSV U3 demonstrated the association between the inhibition of WDSV promoter activity and increasing quantities of OrfA expression vector DNA (Fig. 8D).

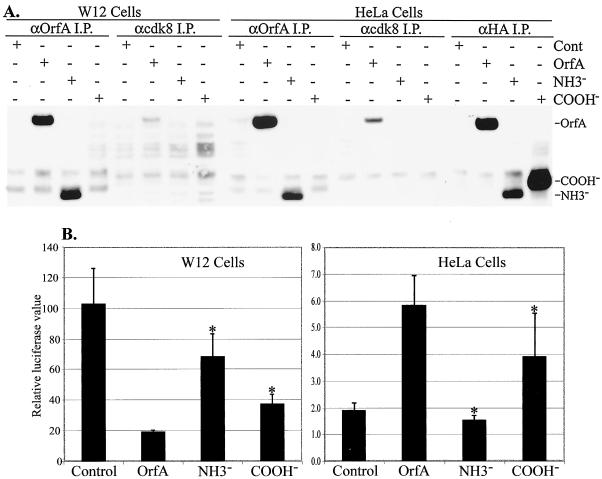

OrfA mutants are characterized by loss of association with cdk8 and by reduced effects on promoter activity.

Two OrfA deletion mutants were cloned in the pKH3 vector and were expressed in HeLa and W12 cells to assess their effects on transcription and their association with cdk8. The amino-terminal-truncated mutant OrfA-NH3− has the first 112 amino acids deleted and corresponds to the predicted products of observed splice variants of the OrfA transcript, OrfA3 and OrfA5 (37, 38). Carboxy-terminal-deleted mutant OrfA-COOH− has the last 78 amino acids deleted, the region containing the predicted coiled-coil domain (Fig. 7). Immunoprecipitations were performed with control, anti-OrfA, and anti-cdk8 antisera. As seen previously, full-length OrfA was coimmunoprecipitated with cdk8 from HeLa and walleye cell lysates (Fig. 9A). Neither OrfA-NH3− nor OrfA-COOH− was coimmunoprecipitated with cdk8. Control immunoprecipitations with antisera reactive to OrfA also failed to precipitate OrfA-COOH−, but it could be precipitated from these lysates with antisera reactive to the HA tag, indicating that the carboxy region is the predominant immune epitope for precipitation by the anti-OrfA antiserum.

FIG. 9.

Analyses of OrfA deletion mutants. (A) Immunoprecipitation (I.P.) of proteins from W12 and HeLa cell lysates with rabbit anti-OrfA, anti-cdk8, and anti-HA sera. Cells were transfected with vector control (Cont), pKH3OrfA (OrfA), pKH3OrfA-NH3− (NH3−), or pKH3OrfA-COOH− (COOH−). Precipitated proteins were detected with mouse monoclonal anti-HA 12CA5, and their relative positions are indicated. (B) Effect of OrfA and deletion mutants on the WDSV core promoter activity in W12 and HeLa cells. All transfections were performed and assayed in triplicate. ∗, statistically significant value (P < 0.05).

In luciferase assays, both of the deletion mutants were significantly less inhibitory of WDSV-U3 promoter activity in W12 cells than OrfA (Fig. 9B; OrfA versus OrfA-NH3−, P < 0.004; OrfA versus OrfA-COOH−, P < 0.007) yet both still caused significant inhibition (OrfA-NH3− versus control, P < 0.03; OrfA-COOH− versus control, P < 0.003). The inhibitory effects of the two mutants were also significantly different (P < 0.01). In HeLa cells, the enhancement of WDSV-U3 promoter activity was completely lost with truncation of the amino terminus (OrfA versus OrfA-NH3−, P < 0.004) and reduced with truncation of the carboxy terminus (OrfA versus OrfA-COOH−, P < 0.043). Overall, the amino-terminal domain appeared to be more important than the carboxy-terminal, coiled-coil region for OrfA function in transcription, whether for the enhancement or inhibition of the WDSV promoter in different cell types.

DISCUSSION

Colocalization and cofractionation of OrfA and Pol II in IGCs were confirmed in this study, and the association of these two proteins was demonstrated by coimmunoprecipitation. Coprecipitation of Pol II with OrfA was achieved only from a stably transfected cell line expressing moderate levels of OrfA. The results demonstrated that OrfA was specifically associated with Pol IIO, the hyperphosphorylated form highly associated with transcription elongation and transcript processing.

cdk8 is the only cyclin-related protein previously identified in IGCs (5). An association of cdk8 and OrfA was detected in a screen of anti-cdk antibodies, and reciprocal experiments demonstrated coprecipitation of cdk8 with anti-OrfA antiserum. Coimmunoprecipitation of a larger native form of cdk8 suggested an association with cdk8, which is part of a large nuclear complex (42). Cyclin C antibodies also coprecipitated OrfA, suggesting that OrfA does not completely displace cyclin C from complexes with cdk8. The stoichiometry of these components is unknown. Displacement of cyclin C by OrfA could dramatically alter cdk8 function or stability, and low levels of cyclin C in cdk8-OrfA complexes, might lead to more-subtle effects on cdk8 function. If OrfA does not disrupt the cdk8-cyclin C interaction at all, then its association may be independent of its cyclin homology, and the transcriptional effects of OrfA would likely be mediated by a conventional cdk8/cyclin C pathway. Still unresolved is the question of whether there is direct physical contact between OrfA and cdk8-cyclin C or whether coimmunoprecipitation is dependent only on the inclusion of all three proteins in a larger, stable complex.

cdk8 and cyclin C are components of the mediator complex, which functions as a coactivator of transcription and which is physically associated with the Pol II holoenzyme (reviewed in reference 34). Similar large, multisubunit complexes such as NAT, SMCC-TRAP, CRSP, and ARC have been isolated from metazoan organisms. They can negatively regulate transcription in vitro by phosphorylating the CTD of Pol II prior to transcription initiation (17) or function as coactivators in transcription assays lacking the general initiation factor TFIIH (1, 8). They downregulate transcription in the presence of TFIIH due to phosphorylation of the cyclin H subunit. They are also bound by the activation domains of activators adenovirus E1A, herpes simplex virus VP16, and Elk1 (8, 15), interactions that are necessary for activation of transcription. In general, these complexes can mediate activator function and repress basal transcription in cell-free systems (42). The primary sequence of cdk8 is highly conserved, as demonstrated by the ability of the anti-human cdk8 to coprecipitate OrfA from walleye cells via endogenous cdk8. This conservation supports the biological relevance of experiments performed with mammalian cells.

The cyclin C yeast homologue, Srb11, was identified by complementation of yeast lacking G1 cyclins, encoded by CLN1 to CLN3 (21, 24, 25), but there is no evidence for the direct regulation of the cell cycle by cyclin C (3). The WDSV retrovirus cyclin, OrfA, also complements G1 cyclin-deficient yeast and was identified as a D-type cyclin based on alignments within the cyclin box motif (23). To clarify this cyclin complementation and the association of OrfA with cdk8, further sequence alignments and secondary structure analyses compared OrfA and human cyclins C and D1. The alignments showed that the homology of OrfA to cyclin C is only slightly better than that of OrfA to cyclin D1. Comparisons of the predicted secondary structures served to illustrate their similar α-helical topologies, but, overall, the results suggest that OrfA may not be a true homologue of any particular cyclin. Predictions of specific protein-protein interactions with cyclins are not yet possible. The cyclin box fold is a general adapter motif involved in both cell cycle control and transcriptional regulation, and its versatility lies in the retention of similar topologies from dissimilar sequences (36). In addition to being found in cyclins, this motif is found in pRB and TFIIB. It remains to be determined whether OrfA associates with cdk8- and cyclin C-containing complexes specifically because of similarities to cyclin C or because of its general cyclin motif or an unrelated structural domain. Deletion of the amino end, including a large portion of the cyclin box and the amino acids predicted to mediate binding to a cdk partner (38), resulted in OrfA dissociation from cdk8 and a significant decline in the inhibition and activation of the WDSV promoter. However, the predicted coiled-coil domain, not present in cyclins C or D, was also required for association with cdk8 and was necessary for full OrfA-mediated inhibition and activation of transcription. Neither deletion yielded an exclusively activating or inhibiting protein, only loss of observed OrfA function, thus excluding a specific OrfA motif that distinguishes activation from inhibition.

Functionally, OrfA emulates cyclin C more than cyclin D in its ability to affect transcription. Inhibition of the WDSV promoter by OrfA was observed previously (47) and fits well with WDSV biology; virus expression is inhibited during tumor development, when only low levels of OrfA and OrfB transcripts are present (7, 37, 38). Inhibition of virus expression may be critical to protect infected cells from immune system- or virus-mediated cell death during growth of host tissue. WDSV mechanisms for the induction of apoptosis in association with virus expression have been identified (W. A. Nudson and S. L. Quackenbush, unpublished data). OrfA's ability to enhance transcription has not been shown previously but fits with the abilities of cyclin C-cdk8 and the mediator complex to affect transcription positively or negatively by mediating transcription factor signals. OrfA enhanced or inhibited transcription in a cell-specific manner, suggesting a general mechanism of transcription control, responsive to the repertoire of transcriptional activators in a given cell type. The moderate degree of the effect is within the range observed for mediator, a transducer of extant signals rather than a potent transcription factor. The effect of OrfA on transcription from the core promoter of WDSV was similar to its effect on transcription from the WDSV LTR, excluding the utilization of cis-acting sequences in the R or U5 region.

Identification of OrfA as a structural and functional homologue of cellular cyclins strongly suggested its role as a transforming factor, and this has been supported by results for transgenic mice (22). We hypothesize that the activity of complexes containing OrfA, cdk8, and cyclin C varies from that of cdk8-cyclin C-containing complexes. Changes could be in the recognition of important substrates of cdk8 phosphorylation, such as cyclin H or the CTD of Pol II. Alternatively, complexes with OrfA may have extended substrate specificity or changes in activity toward specific transcription factors, thereby increasing or decreasing transcription from a subset of promoters. Such general mechanisms may have oncogenic potential through the enhancement or inhibition of proto-oncogene or tumor suppressor expression. It is anticipated that information derived from OrfA function will also help to delineate the role of the mediator complex in control of transcription.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ashley Meagher for the construction of the pGL3 WDSV U3 vector, Jeffrey L. Urbauer for assistance in the analysis and presentation of protein structures, Robert G. Roeder for the cdk8 expression construct, and Matthew Buechner for microscopy facilities.

This research was supported by Research Project Grant RPG-00-313-01-MBC from the American Cancer Society and by National Institutes of Health COBRE award 1P20RR15563 with matching support from the State of Kansas and the University of Kansas. J.R. was supported by National Research Service Award 1 F32 CA88572-01.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akoulitchev, S., S. Chuikov, and D. Reinberg. 2000. TFIIH is negatively regulated by cdk8-containing mediator complexes. Nature 407:102-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson, P., M. P. Goldfarb, and R. A. Weinberg. 1979. A defined subgenomic fragment of in vitro synthesized Moloney sarcoma virus DNA can induce cell transformation upon transfection. Cell 16:63-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barette, C., I. Jariel-Encontre, M. Piechaczyk, and J. Piette. 2001. Human cyclin C protein is stabilized by its associated kinase cdk8, independently of its catalytic activity. Oncogene 20:551-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berger, B., D. B. Wilson, E. Wolf, T. Tonchev, M. Milla, and P. S. Kim. 1995. Predicting coiled coils by use of pairwise residue correlations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:8259-8263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bex, F., A. McDowall, A. Burny, and R. Gaynor. 1997. The human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 transactivator protein Tax colocalizes in unique nuclear structures with NF-κB proteins. J. Virol. 71:3484-3497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowser, P. R., M. J. Wolfe, J. L. Forney, and G. A. Wooster. 1988. Seasonal prevalence of skin tumors from walleye (Stizostedion vitreum) from Oneida Lake, New York. J. Wildl. Dis. 24:292-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowser, P. R., G. A. Wooster, S. L. Quackenbush, R. N. Casey, and J. W. Casey. 1996. Comparison of fall and spring tumors as inocula for experimental transmission of walleye dermal sarcoma. J. Aquat. Anim. Health 8:78-81. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyer, T. G., M. E. D. Martin, E. Lees, R. P. Ricciardi, and A. J. Berk. 1999. Mammalian Srb/Mediator complex is targeted by adenovirus E1A protein. Nature 399:276-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bregman, D. B., L. Du, S. van der Zee, and S. L. Warren. 1995. Transcription-dependent redistribution of the large subunit of RNA polymerase II to discrete nuclear domains. J. Cell Biol. 129:287-298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen, H.-C., P. A. Appeddu, H. Isoda, and J.-L. Guan. 1996. Phosphorylation of tyrosine 397 in focal adhesion kinase is required for binding phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 271:26329-26334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Combet, C., C. Blanchet, C. Geourjon, and G. Deleage. 2000. NPS@: network protein sequence analysis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 25:147-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Copeland, N. G., and G. M. Cooper. 1979. Transfection by exogenous and endogenous murine retrovirus DNAs. Cell 16:347-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dignam, J. D., R. M. Lebovitz, and R. G. Roeder. 1983. Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res. 11:1475-1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gey, G. O., W. D. Coffman, and M. T. Kubicek. 1952. Tissue culture studies of the proliferative capacity of cervical carcinoma and normal epithelium. Cancer Res. 12:264-265. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gold, M. O., J.-P. Tassan, E. A. Nigg, A. P. Rice, and C. H. Herrmann. 1996. Viral transactivators E1A and VP16 interact with a large complex that is associated with CTD kinase activity and contains CDK8. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:3771-3777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gu, W., S. Malik, M. Ito, C.-X. Yuan, J. D. Fondell, X. Zhang, E. Martinez, J. Qin, and R. G. Roeder. 1999. A novel human SRB/MED-containing cofactor complex, SMCC, involved in transcription regulation. Mol. Cell 3:97-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hengartner, C. J., V. E. Myer, S.-M. Liao, C. J. Wilson, S. S. Koh, and R. A. Young. 1998. Temporal regulation of RNA polymerase II by Srb10 and Kin28 cyclin-dependent kinases. Mol. Cell 2:43-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holzschu, D. L., D. Martineau, S. K. Fodor, V. M. Vogt, P. R. Bowser, and J. W. Casey. 1995. Nucleotide sequence and protein analysis of a complex piscine retrovirus, walleye dermal sarcoma virus. J. Virol. 69:5320-5331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jainchill, J. L., S. A. Aaronson, and G. J. Todaro. 1969. Murine sarcoma and leukemia viruses: assay using clonal lines of contact-inhibited mouse cells. J. Virol. 4:549-553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim, E., L. Du, D. B. Bregman, and S. L. Warren. 1997. Splicing factors associate with hyperphosphorylated RNA polymerase II in the absence of pre-mRNA. J. Cell Biol. 136:19-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lahue, E. E., A. V. Smith, and T. L. Orr-Weaver. 1991. A novel cyclin gene from Drosophila complements CLN function in yeast. Genes Dev. 5:2166-2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lairmore, M. D., J. R. Stanley, S. A. Weber, and D. L. Holzschu. 2000. Squamous epithelial proliferation induced by walleye dermal sarcoma retrovirus cyclin in transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6114-6119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LaPierre, L. A., J. W. Casey, and D. L. Holzschu. 1998. Walleye retroviruses associated with skin tumors and hyperplasias encode cyclin D homologs. J. Virol. 72:8765-8771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leopold, P., and P. H. O'Farrell. 1991. An evolutionarily conserved cyclin homolog from Drosophila rescues yeast deficient in G1 cyclins. Cell 66:1207-1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lew, D. J., V. Dulic, and S. I. Reed. 1991. Isolation of three novel human cyclins by rescue of G1 cyclin (Cln) function in yeast. Cell 66:1197-1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liao, S. M., J. Zhang, D. A. Jeffery, A. J. Koleske, C. M. Thompson, D. M. Chao, M. Viljoen, H. J. van Vuuren, and R. A. Young. 1995. A kinase-cyclin pair in the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Nature 9:121-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luckow, B., and G. Schultz. 1987. CAT constructions with multiple unique restriction sites for the functional analysis of eukaryotic promoters and regulatory elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 15:5490.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martineau, D., P. R. Bowser, R. R. Renshaw, and J. W. Casey. 1992. Molecular characterization of a unique retrovirus associated with a fish tumor. J. Virol. 66:596-599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martineau, D., R. Renshaw, J. R. Williams, J. W. Casey, and P. R. Bowser. 1991. A large unintegrated retrovirus DNA species present in a dermal tumor of walleye Stizostedion vitreum. Dis. Aquat. Org. 10:153-158. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mattingly, R. R., A. Sorisky, M. R. Brann, and I. G. Macara. 1994. Muscarinic receptors transform NIH 3T3 cells through a ras-dependent signaling pathway inhibited by the ras-GTPase-activating protein SH3 domain. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:7943-7952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mayeda, A., and A. R. Krainer. 1999. Preparation of HeLa cell nuclear and cytosolic S100 extracts for in vitro splicing. Methods Mol. Biol. 118:309-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mintz, P. J., S. D. Patterson, A. F. Neuwald, C. S. Spahr, and D. L. Spector. 1999. Purification and biochemical characterization of interchromatin granule clusters. EMBO J. 18:4308-4320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mortillaro, M. J., B. J. Blencowe, X. Wei, H. Nakayasu, L. Du, S. L. Warren, P. A. Sharp, and R. Berezney. 1996. A hyperphosphorylated form of the large subunit of RNA polymerase II is associated with splicing complexes and the nuclear matrix. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:8253-8257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naar, A. M., B. D. Lemon, and R. Tjian. 2001. Transcriptional coactivator complexes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70:475-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson-Rees, W. A., R. B. Owens, P. Arnstein, and A. J. Kniazeff. 1976. Source, alterations, characteristics and use of a new dog cell line (Cf2Th). In Vitro 12:665-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noble, M. E. M., J. A. Endicott, N. R. Brown, and L. N. Johnson. 1997. The cyclin box fold: protein recognition in cell-cycle and transcription control. Trends Biochem. Sci. 22:482-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quackenbush, S. L., D. L. Holzschu, P. R. Bowser, and J. W. Casey. 1997. Transcriptional analysis of walleye dermal sarcoma virus (WDSV). Virology 237:107-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rovnak, J., J. W. Casey, and S. L. Quackenbush. 2001. Intracellular targeting of walleye dermal sarcoma virus Orf A (rv-cyclin). Virology 280:31-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tassan, J.-P., M. Jaquenoud, P. Leopold, S. J. Schultz, and E. A. Nigg. 1995. Identification of human cyclin-dependent kinase 8, a putative kinase partner for cyclin C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:8871-8875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walker, R. 1969. Virus associated with epidermal hyperplasia in fish. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 31:195-207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang, G., G. T. Cantin, J. L. Stevens, and A. J. Berk. 2001. Characterization of Mediator complexes from HeLa cell nuclear extract. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:4604-4613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wolf, E., P. S. Kim, and B. Berger. 1997. MultiCoil: a program for predicting two- and three-stranded coiled coils. Protein Sci. 6:1179-1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wolf, K., and J. A. Mann. 1980. Poikilotherm vertebrate cell lines and viruses: a current listing for fishes. Fish Dis. Diagn. 16:168-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamamoto, T., R. K. Kelly, and O. Nielsen. 1985. Morphological differentiation of virus-associated skin tumors of walleye (Stizostedion vitreum vitreum). Fish Pathol. 20:361-372. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamamoto, T., R. D. MacDonald, D. C. Gillespie, and R. K. Kelly. 1976. Viruses associated with lymphocystis and dermal sarcoma of walleye (Stizostedion vitreum vitreum). J. Fish Res. Board Can. 33:2408-2419. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang, Z., and D. Martineau. 1999. Walleye dermal sarcoma virus: OrfA N-terminal end inhibits the activity of a reporter gene directed by eukaryotic promoters and has a negative effect on the growth of fish and mammalian cells. J. Virol. 73:8884-8889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]