Abstract

Background

Changes in aboveground plant species diversity as well as variations of environmental conditions such as exposure of ecosystems to elevated concentrations of atmospheric carbon dioxide may lead to changes in metabolic activity, composition and diversity of belowground microbial communities, both bacterial and fungal.

Results

We examined soil samples taken from a biodiversity × CO2 grassland experiment where replicate plots harboring 5, 12, or 31 different plant species had been exposed to ambient or elevated (600 ppm) levels of carbon dioxide for 5 years. Analysis of soil bacterial communities in these plots by temporal temperature gradient gel electrophoresis (TTGE) showed that dominant soil bacterial populations varied only very little between different experimental treatments. These populations seem to be ubiquitous. Likewise, screening of samples on a high-resolution level by terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP) showed that increased levels of carbon dioxide had no significant influence on both soil bacterial community composition (appearance and frequency of operational taxonomic units, OTUs) and on bacterial richness (total number of different OTUs). In contrast, differences in plant diversity levels had a significant effect on bacterial composition but no influence on bacterial richness. Regarding species level, several bacterial species were found only in specific plots and were related to elevated carbon dioxide or varying plant diversity levels. For example, analysis of T-RFLP showed that the occurrence of Salmonella typhimurium was significantly increased in plots exposed to elevated CO2 (P < 0.05).

Conclusion

Plant diversity levels are affecting bacterial composition (bacterial types and their frequency of occurrence). Elevated carbon dioxide does not lead to quantitative alteration (bacterial richness), whereas plant diversity is responsible for qualitative changes (bacterial diversity).

Background

Knowledge on the relationship between plant communities and soil microbial communities is still lacking in large parts, although recent ecological research focuses on potentially beneficial effects of biodiversity on ecosystem processes, including the response of ecosystems to environmental changes such as increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide levels [1-3].

Soil microorganisms are the driving force behind soil organic matter transformations such as mineralization of organic compounds. These transformations are the basis of plant decomposition, soil aggregation, nutrient availability, soil fertility and, therefore in general, soil ecosystem functioning. However, these transformations might be significantly influenced by different levels of plant diversity which can affect soil microbial communities regarding e.g. population sizes, activities and taxonomic composition (see e.g. [4-8]. In addition, anthropogenic activities resulting in e.g. increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations might induce specific responses (stimulation, inhibition) of soil microbes (bacteria, fungi) possibly mediated via altered growth of the plant communities [9-12].

On both local and global scales, the wealth of soil microbial diversity is poorly appreciated and, therefore, the importance of soil organisms has been largely neglected [13]. A profound understanding of soil biodiversity and its relation to ecosystem functions is vital for long-term sustainable soils [14]. However, detailed knowledge on the control of ecosystem processes and functioning by this diversity is still lacking [15].

Soil microbial communities are characterized by two levels of diversity, namely genetic diversity and functional diversity: a high level of genetic diversity is found in many different types of soil (e.g. [16]). Recent detailed investigations based on molecular methods such as DNA-DNA-hybridization, 16S rRNA sequencing, PCR-based methods with primers derived from rRNA sequencing, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), or immunological techniques revealed that soil microbial communities are composed of a vast variety of microorganisms resulting in complex microbial interactions and nutrient flows [17]. The composition of these communities is usually subject to seasonal fluctuations and may vary between different locations. In addition, organisms are not homogeneously distributed over the whole environment [18,19]. Regarding soil, it has been hypothesized that significant reductions in microbial diversity due to environmental changes are unlikely and that the genetic diversity does not represent a major factor that limits ecosystem functioning [15].

Elevated atmospheric CO2 can have indirect effects on soil microbial communities via altered plant inputs (litter, exudates, rhizodeposition). As result, soil microbial communities and their activities are stimulated: increased carbon flow might affect the portion of culturable soil bacteria and might favor fast growing organisms [20]. In turn, also the nitrogen flow (e.g. N-fixation) in soil ecosystems can be influenced by elevated CO2 [21], although nitrogen concentration in plant litter is not affected [22]. Therefore, microbial community composition and functional diversity are subject to changes under changing environmental conditions and the populations will adapt to the new conditions.

We examined soil samples from experimental grassland plots where plant communities of different species richness had been exposed for 5 years to ambient or elevated levels of carbon dioxide and assessed soil microbial community structure. The two main questions were: (i) what is the effect of elevated CO2 and plant diversity on bacterial richness? (ii) to which extent are treatment-induced effects reflected in changes in the structural composition of the soil bacterial community? An innovative feature of this study is the combination of an experimental-ecological approach and a microbiological approach to characterize the microbial populations involved. We determined the total number of soil microbial operational taxonomic units (OTUs) as a measure for "bacterial richness" as well as the dissimilitude of these OTUs as a measure for bacterial composition applying analyses of terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP).

Results

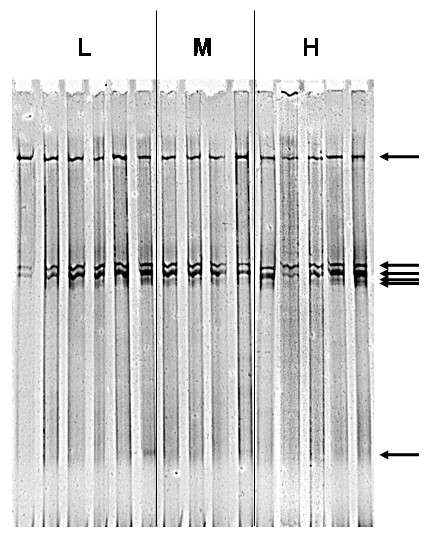

Dominant soil microbial populations (as determined by TTGE) varied only very little between different soil samples (Fig. 1). Only a few bands were observed. The band patterns of the total community 16S rDNA showed that bacterial communities consisted of five to six bacterial groups that were present in all of the differently treated soils examined. These populations seemed to be ubiquitous and occurred in all samples, independently of experimental treatments or sampling location. Only very rarely additional OTUs were detected (e.g. lane 13). As a consequence, we found that soil bacterial community structure was only poorly resolved when analyzing bacterial populations by TTGE. In our case, the resolution of TTGE was too low for the monitoring of soil microbial diversity.

Figure 1.

Example of TTGE band pattern (arrow: operational taxonomic unit, OTU) of DNA extracted from soil samples exposed to different levels of plant biodiversity and carbon dioxide. H: high diversity level (31 plant species); M: medium diversity level (12 plant species); L: low diversity level (5 plant species). Image was photographically enhanced using Photoshop.

To improve analysis on a high resolution level, soil microbial populations were assessed by T-RFLP [23]. Different TRF'-types were applied, namely (i) 3'-BstU, (ii) 5'-BstU, (iii) 3'-MNL, and (iv) 5'-MNL (see Material & Methods). Combination (i), (ii) and (iii) yielded 20, 21 and 19 operational taxonomic units (OTUs), respectively, whereas 44 OTUs were obtained from combination (iv). Every of the four different TRF'-types applied may constitute on its own a possibility to determine soil microbial diversity. A combined analysis, however, allows more powerful statistical analysis and to monitor soil microbial diversity more comprehensively regarding the different OTUs present.

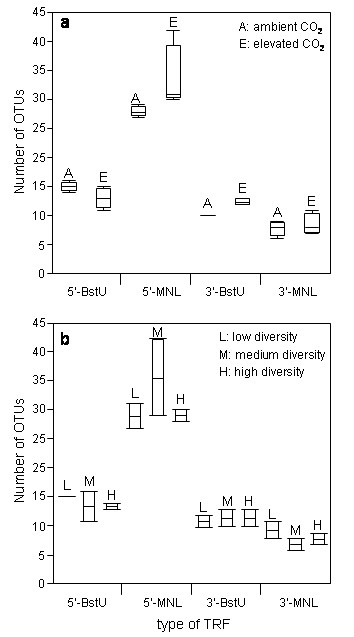

However, combining the information obtained from all assays (enzyme/label combinations) showed that elevated carbon dioxide levels does not significantly influence the number of soil microbial community OTUs (= "bacterial richness") (Fig 2a). Moreover, also different plant diversity levels showed no significant effect on this bacterial richness measure (Fig. 2b). No interaction was detected between carbon-dioxide and diversity treatments.

Figure 2.

Number of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) observed in relation to different restriction enzyme/fluorescent label combinations. Boxes give median with upper line representing 75th percentile and lower line 25th percentile; whiskers extend to the most extreme data points with range not more than 1.5 times the interquartile range from the box. Number of OTU is a measure for "bacterial richness". a) elevated carbon dioxide in comparison to ambient levels; b) three different plant diversity levels.

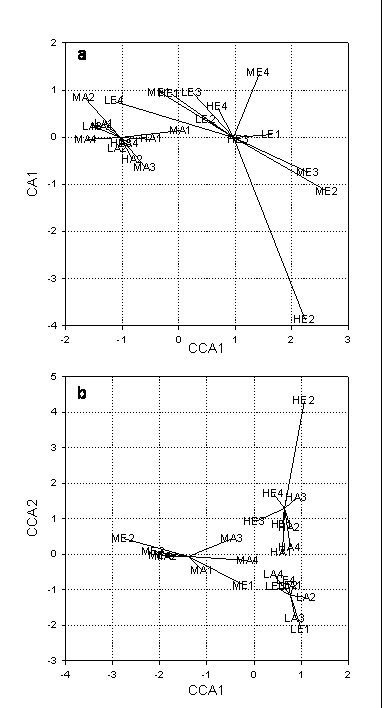

To analyze bacterial composition, all band patterns of the different enzyme/label combinations were analyzed in combination by canonical correspondence analysis. Occurrence of OTUs within the four replicates of each treatment combination was analyzed separately, but additionally also the frequency of occurrence of OTUs within the four replicates was assessed. As shown in Fig. 3b, plant diversity had a significant (P < 0.05) effect on bacterial composition. Three distinct separate clusters can be observed, each related to one of the three different plant diversity levels. In contrast, elevated carbon dioxide did not affect bacterial composition (Fig. 3a). Although a clustered pattern was observed, a significant difference was not detectable.

Figure 3.

Canonical correspondence analysis of plots exposed to different carbon dioxide levels (a); plots exposed to different plant diversity levels (b). A: ambient carbon dioxide; E: elevated carbon dioxide; H: high plant diversity; M: medium plant diversity; L: low plant diversity; numbers 1, 2, 3, and 4: four replicates.

All TRFs were compared with the TAP-database. Only bacterial strains simultaneously matching maximally two types of enzyme/label combinations were considered (Table 1). No strains simultaneously matching three or four enzyme/label combinations were detected. In several cases, results yielded more than one bacterial species for the same enzyme/label combination. The frequency of occurrence of the different combinations of TRFs and bacteria belonging to them was variable. Several bacterial strains were found only in specific plots and were obviously related to elevated carbon dioxide or varying plant diversity levels: Escherichia coli and Ferrobacterium limneticum were detected only in three samples, all showing a high plant diversity level. The patterns referring to the unidentified strain from Lake Gossenkoellesee was found only in samples with medium plant diversity (12 different plant species). Clostridium perfringens, Sulfobacillus disulfidooxidans, Kitasatospora paracochleata, Kitasatospora melanogena and Kitasatospora kifuense were found only in plots with elevated carbon dioxide levels. Furthermore, analyses of the different TRF patterns by logistic regression showed that the probability of occurrence of Salmonella typhimurium in plots treated by elevated CO2 was significantly increased (P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Organisms identified by double matches of restriction enzyme/fluorescent label combinations

| Enzyme/label combination | Fragment | Organism identified, species | strain; type culture collection number | number of plots (out of 24) where strain was detected |

| Bst-FAM × BstU-JOE | 226/173 | Clostridium botulinum | 202F; ATCC 23387 | 5 |

| Clostridium butyricum | E.VI.3.6.1.; NCIMB 8082 | |||

| Clostridium butyricum | MMP3; DSM 2478 | |||

| Clostridium butyricum | ATCC 43755 | |||

| 236/173 | Bacillus subtilis | 7 | ||

| unidentified species | 16SX-1 | |||

| unidentified species | 16SX-2 | |||

| BstU-JOE × MNL-JOE | 171/93 | Ralstonia solanacearum | ACH 0732 | 24 |

| 171/93 | Piscirickettsia salmonis | 5 | ||

| 173/93 | Pirellula sp. (uncultered) | clone 5H12 | 5 | |

| Thermoanaerobacterium saccharolyticum | B6A-RI | |||

| 275/93 | Ferribacterium limneticum | cda-1 | 3 | |

| Escherichia coli chloroplast of Marchantia polymorpha | ||||

| BstU-JOE × MNL-FAM | 173/210 | symbiont of Crithidia sp. | 24 | |

| 275/205 | unidentified strain from Gossenköllesee | 3 | ||

| 275/211 | Azoarcus sp. | PH002 | 7 | |

| Azoarcus sp. | CR23 | |||

| Azoarcus sp. | FL05 | |||

| unidentified species | clone A1–13 | |||

| unidentified species | cloneSJA-62 | |||

| 275/217 | Salmonella typhimurium | E10 NCTC 8391 | 15 | |

| 275/226 | unidentified species | clone SJA-47 | 2 | |

| MNL-JOE × BstU-FAM | 226/93 | Clostridium algidicarnis | NCFB 2931 (T) | 1 |

| BstU-FAM × MNL-FAM | 103/211 | unidentified species | clone SJA-112 | 11 |

| 219/426 | Frankia sp. | L27 | 1 | |

| Kibdelosporangium aridum subsp. aridum | ||||

| Mycobacterium asiaticum | N6IH; ATCC 25276 | |||

| 221/129 | Nocardia crassostreae | RB1 | 22 | |

| Nocardia crassostreae | OB3 | |||

| 221/183 | Sulfobacillus disulfidooxidans | SD-11 | 12 | |

| Kitasatospora paracochleata | 14769 | |||

| Kitasatospora melanogena | JCM 3337 | |||

| Kitasatospora kifuense | JCM 9081 | |||

| 236/138 | Leuconostoc citreum | NCDO 2787 | 7 | |

| Leuconostoc lactis | ATCC 19256 | |||

| Leuconostoc mesenteroides subsp. mesenteroides | ATCC 8293 | |||

| 388/210 | Oxalobacter formigenes | BLISS | 12 | |

| 390/211 | Pseudomonas sp. | B13 | 11 | |

| MNL-FAM × MNL-JOE | 134/93 | Clostridium perfringens | CPN50 | 2 |

Discussion

Several studies found a positive relationship between elevated CO2 and bacterial richness [11], whereas others found a negative effect [24]. Therefore, results show a certain inconsistency [25,26]. In our case, considering the negligible effect of elevated carbon dioxide and of different plant diversity levels on the number of OTUs detected, it can be concluded that both experimental treatments had no effect on bacterial richness. Furthermore, elevated carbon dioxide concentrations did not affect soil microbial composition as also reported by Griffiths et al. [27] or Zak et al [28]. In contrast, aboveground plant diversity significantly affected belowground bacterial composition. These findings suggest that the soil microbial composition is mainly related to plant diversity (assuming that different plant species might harbor specific rhizospheric microbial populations) rather than altered soil carbon fluxes induced by elevated atmospheric CO2 and subsequently increased photosynthetic activities.

Our analyses showed that increased levels of carbon dioxide had no influence on soil microbial community composition (Fig. 3a). Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) showed no statistical difference between plots at ambient CO2 level compared with plots with elevated CO2 level. Differences in rhizosphere carbon allocation (and subsequent alterations of soil microbial communities) have been postulated and observed when plants were exposed to increased CO2 levels in other studies, e.g. changed quality of litter, increase in root exudates and stimulation of rhizodeposition [29,30]. Consequently, effects on soil microbial community composition might occur [9]. However, in our case the aboveground exposure of plants to elevated carbon dioxide was not reflected in a belowground change of bacterial composition.

In contrast to the CO2 treatment, plant diversity had a significant effect on belowground microbial community composition (Fig. 3b). That is, on a genetic level, bacterial community structure in soil can be differentiated in relation to different plant diversity levels. This is in agreement with studies reported earlier on the functional microbial diversity in soil samples exposed to different plant diversity levels [4]. The differentiation between the three different plant diversity levels on the basis of the soil bacterial composition suggests that all three plant diversities exhibit their own bacterial environment.

The land where our experimental plots have been set up, has a long-time record as pasture for cows. Therefore, the occurrence of Escherichia coli and Salmonella sp. is not surprising since these organisms easily originate from cowpats as shown by Muirhead et al., [31] and Johannessen et al. [32]. Anoxic micro-habitats might occur in soil allowing the existence and survival of anaerobes such as Clostridia. In addition, Clostridium is an spore-forming organism able to form spores which can easily survive in soil for prolonged time periods. Since Ralstonia solanacearum is commonly found in soil as plant pathogen but also free-living when host plants are absent [33], the occurrence is not unusual. Therefore, we conclude that our findings reflect the true state of the soil investigated.

As stated by other authors [34], soil type might be the key determinant for soil microbial communities. Since the soil type was the same throughout all experimental plots, we believe that the differences we have observed reflect the true state of the soil depending on the different treatments e.g. elevated CO2 or plant diversity.

Conclusion

In summary, plant diversity levels are affecting bacterial composition (bacterial types and their frequency of occurrence). Elevated carbon dioxide does not lead to quantitative alteration (bacterial richness), whereas plant diversity is responsible for qualitative changes (bacterial diversity).

Methods

Site description

Soil samples were collected from a nutrient-poor, calcareous experimental grassland in northwestern Switzerland (for a more detailed site description see [35][36][37]). The field site is located on a southwest-facing slope in the Jura mountains of Switzerland near the village of Nenzlingen (47°33'N 7°34'E). Detailed information on soil characteristics have been already published elsewhere. As described by Niklaus et al. [38], "the Rendzina-type soil, which is typical for these habitats, consists of a 10 to 15 cm neutral to slightly basic (pH approx. 7.8) silty clay loam top soil and is underlain with calcareous debris. In the top 10 cm, the horizon, where most of the fine roots occur, organic C and N are approx. 3.9% and 0.33%, respectively". Typically, the climate in this area is characterized by cold wet springs, warm drought-prone summers, pleasant falls, and moderate winters [39].

Experimental design

Twenty-four plots (1.27 m2 each) received factorial combinations of two carbon dioxide treatments at three plant species diversity levels. CO2 treatments were (i) 12 open-top, open-bottom chambers with ambient CO2 (approx. 350 ppm) ["A"]; 12 open-top, open-bottom chambers with elevated CO2 (approx. 600–650 ppm) ["E"] using the Screen-Aided CO2 Control system (SACC) for carbon dioxide exposure [35]. The plant species diversity levels were (i) 31 species ("high" diversity level) ["H"], 12 species ("medium" diversity level, all species also present in H) ["M"], and 5 species ("low" diversity level, all species also present in M and H) per plot ["L"]. Plants were selected from three functional groups grasses, herbs and legumes [36]. Diversity treatments were established in September 1993, prior to the onset of CO2 treatment which started in early April 1994. Each treatment combination (carbon dioxide level × plant diversity level) was replicated four times. The treatment combinations are accordingly named "HA", "MA", "LA", "HE", "ME", and "LE".

Soil sampling

Soil sampling took place in spring 1999. Six samples were taken from the top layer (0–10 cm) from each plot. Soil coring was done with a core bit which was sterilized by flaming with ethanol prior to every sampling. Three samples were pooled in a sterile plastic tube (Greiner AG, Kremsmünster, Austria), kept on ice and immediately frozen at -80°C after returning to the laboratory, resulting in two independent samples from each plot.

DNA extraction

Prior to DNA extraction, all samples were lyophilized over night and ground in sterile plastic tubes with sterile glass beads. Total community DNA was extracted using the Ultra Clean Soil DNA Kit (MO BIO Laboratories, Inc.), following the manufacturer's instructions. DNA extracts were stored at -20°C.

Temporal temperature gradient gel electrophoresis (TTGE)

Samples were prepared by amplifying approximately a 500-bp piece of bacterial 16S rRNA gene, using the bacterial universal primers 341F (5'CCTACGGGAGGCAGC AG-3') and 907R-GCclamp (5'CGCCCGCCGCGCGCGGCGGGCGGGGCGGG GGCACGGGGGGCCGTCAAATTCMTTTRAGTTT-3'). TTGE was performed in 1.25 × TAE buffer (1 × TAE corresponds to 40 mM Tris-acetate, 20 mM acetic acid, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.3) for 7 h. For analysis of bacterial 16S rDNA fragments, gels were run at 60 V over a temperature range of 60–70°C increasing at a rate of 1.4°C/h.

Terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP)

16S rRNA genes were amplified using the eubacterial universal primer combination of 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM)-labeled primer 27F (5'-AGAGTT-TGA-TCC-TGG-CTC-AG-3') and 6-carboxyfluorescein (JOE)-labeled primer 1525R (5'-AAG-GAG-GTG-WTC-CAR-CC-3'). PCR amplification parameters were as follows: 94°C and 2 min of initial melt and polymerase activation; 35 amplification cycles of 94°C, 30 sec; 55°C, 30 sec; and 72°C, 2.5 min; and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min in a thermocycler (Biometra). The standard reaction mixture contained in a total volume of 100 μl, 1 × JumpStart ReadyMix Taq (Sigma), 0.4 μM concentration of each primer (Microsynth GmbH, Balgach, Switzerland) and genomic DNA (< 60 ng). The fluorescently labeled products were purified with the MinElute Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the protocol provided by the supplier and were digested for 6 h at 37°C with restriction enzyme MNL1 (MBI Fermentas, St. Leon-Rot, Germany) or, alternatively, for 6 h at 60°C with the restriction enzyme BstU1 (New England Biolabs, Beverly, USA). T-RFLP analysis was carried out on an ABI 310 genetic analyzer (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.) with Genescan software and an internal size standard (ROX 500). Cutoffs were applied (5 base pairs to 480 base pairs). Peaks with < 5% of maximum intensity were neglected. Alignment was done using standards size Gene scan 500. Position tolerance was < 0.5%. All together, FAM-labeled 5'-ends and JOE-labeled 3'-ends of the PCR-products cut by two different restriction enzymes resulted in four different types of terminal restriction fragments (TRF), namely (i) 3'-BstU, (ii) 5'-BstU, (iii) 3'-MNL, and (iv) 5'-MNL. Resulting TRFs were compared with the results of a virtual search for TRFs with the T-RFLP analysis program (denoted as TAP T-RFLP) [40].

Statistical analysis

Modeling and canonical correspondence analysis were done with the open source software package R [41]. In particular, canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) – a multivariate analysis method derived from correspondence analysis – was performed to compare the similarity of band patterns obtained from T-RFLP. All data were checked for normal distribution and transformed if necessary.

Authors' contributions

All experimental work was carried out by DG under the supervision of BS and HB. BS provided also statistical help. HB was the principal investigator. DG and HB wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from Swiss National Science Foundation (BS and HB) and through COST action 831 (HB).

Contributor Information

Dominique Grüter, Email: dgrueter@uwinst.unizh.ch.

Bernhard Schmid, Email: bschmid@uwinst.unizh.ch.

Helmut Brandl, Email: hbrandl@uwinst.unizh.ch.

References

- Schmid B, Joshi J, Schläpfer F. Empirical evidence for biodiversity-ecosystem functioning relationships. In: Kinzig A, Pacala S, Tilman D, editor. The Functional Consequences of Biodiversity: Empirical Progress and Theoretical Extensions. Princeton, USA: Princeton University Press; 2002. pp. 120–168. [Google Scholar]

- Kohut R. The long-term effects of carbon dioxide on natural systems issues and research needs. Environ Int. 2003;29:171–180. doi: 10.1016/S0160-4120(02)00160-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavaleta ES, Shaw MR, Chiariello NR, Mooney HA, Field CB. Additive effects of simulated climate changes, elevated CO2, and nitrogen deposition on grassland diversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:7650–7654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0932734100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan A, Meyer AH, Schmid B. Plant diversity positively affects soil bacterial diversity in experimental grassland ecosystems. J Ecol. 2000;88:988–998. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2745.2000.00510.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalchuk GA, Buma DS, de Boer W, Klinkhamer PGL, van Veen JA. Effects of above-ground plant species composition and diversity on the diversity of soil-borne microorganisms. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek . 2002;81:509–520. doi: 10.1023/A:1020565523615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Deyn GB, Raaijmakers CE, Van der Putten WH. Plant community development is affected by nutrients and soil biota. J Ecol. 2004;92:824–834. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-0477.2004.00924.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartelt Ryser J, Joshi J, Schmid B, Brandl H, Balser T. Carryover effects of soil inocula from a plant biodiversity experiment on subsequent plant growth. Perspect Plant Ecol Evol Syst. 2005;7:27–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ppees.2004.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonkowski M, Roy J. Soil microbial diversity and soil functioning affect competition among grasses in experimental microcosms. Oecologia. 2005;143:232–240. doi: 10.1007/s00442-004-1790-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadowski MJ, Schortemeyer M. Soil microbial responses to increased concentrations of atmospheric CO2. Global Change Biol. 1997;3:217–224. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2486.1997.00078.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones TH, Thompson LJ, Lawton JH, Bezemer TM, Bardgett RD, Blackburn TM, Bruce KD, Cannon PF, Hall GS, Hartley SE, Howson G, Jones CG, Kampichler C, Kandeler E, Ritchie DA. Impacts of rising atmospheric carbon dioxide on model terrestrial ecosystems. Science. 1998;280:441–443. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5362.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marilley L, Hartwig UA, Aragno M. Influence of an elevated atmospheric CO2 content on soil and rhizosphere bacterial communities beneath Lolium perenne and Trifolium repens under field conditions. Microb Ecol. 1999;38:39–49. doi: 10.1007/s002489900155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montealegre CM, van Kessel C, Blumenthal JM, Hur HG, Hartwig UA, Sadowsky MJ. Elevated atmospheric CO2 alters microbial population structure in a pasture ecosystem. Global Change Biol . 2000;6:475–482. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2486.2000.00326.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wall DH, Lynch JM. Soil biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. In: Balazs E, Galante E, Lynch JM, Schepers JS, Toutant JP, Werner D, Werry PATJ, editor. Biological Resource Management Connecting Science and Policy. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2000. pp. 283–290. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney HA, Cushman JH, Medina E, Sala OE, Schulze ED. What we have learned about the ecosystem functioning of biodiversity. In: Mooney HA, Cushman JH, Medina E, Sala OE, Schulze ED, editor. Functional Roles of Biodiversity – A Global Perspective. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 1996. pp. 475–484. [Google Scholar]

- Balser TC, Kinzig AP, Firestone MK. Linking soil microbial communities and ecosystem functioning. In: Kinzig A, Pacala S, Tilman D, editor. The Functional Consequences of Biodiversity: Empirical Progress and Theoretical Extensions. Princeton, USA: Princeton University Press; 2001. pp. 265–293. [Google Scholar]

- Torsvik V, Goksoyr J, Daae FL. High diversity in DNA of soil bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:782–787. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.3.782-787.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torsvik V, Ovreas L. Microbial diversity and function in soil: from genes to ecosystems. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2002;5:240–245. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(02)00324-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunan N, Wu KJ, Young IM, Crawford JW, Ritz K. 2003. Spatial distribution of bacterial communities and their relationships with the micro-architecture of soil. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2003;44:203–215. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6496(03)00027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranjard L, Richaume A. Quantitative and qualitative microscale distribution of bacteria in soil. Res Microbiol. 2001;152:707–716. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2508(01)01251-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson E, Hall JM, Rattray EAS, Griffiths BS, Ritz K, Killham K. Effect of elevated CO2 on rhizosphere carbon flow and soil microbial processes. Global Change Biol. 1997;3:363–377. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2486.1997.t01-1-00088.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soussana JF, Hartwig UA. The effects of elevated CO2 on symbiontic N2 fixation: a link between the carbon and nitrogen cycles in grassland ecosystems. Plant Soil. 1996;187:321–332. doi: 10.1007/BF00017097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig UA, Lüscher A, Daepp M, Blum H, Soussana JF, Nösberger J. Due to symbiotic N2 fixation, five years of elevated atmospheric pCO2 had no effect on the N concentration of plant litter in fertile, mixed grassland. Plant Soil. 2000;224:43–50. doi: 10.1023/A:1004601915836. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu WT, Marsh T, Cheng H, Forney LJ. Characterization of microbial diversity by determining terminal restriction fragment length polymorphisms of genes encoding 16S rRNA. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4516–4522. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4516-4522.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge A, Paterson E, Grayston SJ, Campbell CD, Ord BG, Killham K. Characterisation and microbial utilisation of exudate material from the rhizosphere of Lolium perenne grown under CO2 enrichment. Soil Biol Biochem. 1998;30:1033–1043. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(97)00269-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whipps JM. Effect of CO2 concentration on growth, carbon distribution and loss of carbon from the roots of maize. J Exp Bot. 1985;36:644–651. [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill EG, Luxmoore RJ, Norby RJ. Elevated atmospheric CO2 effects on seedling growth, nutrient uptake, and rhizosphere bacterial populations of Liriodendron tulipifera L. Plant Soil. 1987;104:3–11. doi: 10.1007/BF02370618. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zak DR, Ringelberg DB, Pregitzer KS, Randlett DL, White DC, Curtis PS. Soil microbial communities beneath Populus grandidentata crown under elevated atmospheric CO2. Ecol Appl. 1996;6:257–262. [Google Scholar]

- Fangmeier A, De Temmerman L, Mortensen L, Kemp K, Burke J, Mitchell R, van Oijen M, Weigel HJ. Effects on nutrient and on grain quality in spring wheat crops grown under elevated CO2 concentrations and stress conditions in the European, multiple-site experiment 'ESPACE-wheat'. Eur J Agron. 1999;10:215–229. doi: 10.1016/S1161-0301(99)00012-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths BS, Ritz K, Ebblewhite N, Paterson E, Killham K. Ryegrass rhizosphere microbial community structure under elevated carbon dioxide concentrations, with observations on wheat rhizosphere. Soil Biol Biochem. 1998;30:315–321. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(97)00133-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pendall E, Mosier AR, Morgan JA. Rhizodeposition stimulated by elevated CO2 in a semiarid grassland. New Phytol. 2004;162:447–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01054.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muirhead RW, Collins RP, Bremer PJ. Numbers and transported state of Escherichia coliin runoff direct from fresh cowpat under simulated rainfall. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2006;42:83–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2005.01823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannessen GS, Froseth RB, Solemdal L, Jarp J, Wasteson Y, Rorvik LM. Influence of bovine manure as fertilizer on the biological quality of organic Iceberg lettuce. J Appl Microbiol. 2004;96:787–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genin S, Boucher C. Lessons learned from the genome analysis of Ralstonia solanacearum. Ann Rev Phytopathol. 2004;42:107–134. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.42.011204.104301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossio DA, Girvan MS, Verchot L, Bullimore J, Borelli T, Albrecht A, Scow KM, Ball AS, Pretty JN, Osborn AM. Soil microbial community response to land use change in an agricultural landscape of Western Kenya. Microb Ecol. 2000;49:50–62. doi: 10.1007/s00248-003-0209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leadley PW, Niklaus P, Stocker R, Körner C. Screen-aided CO2 control (SACC): a middle ground between FACE and open-top chambers. Acta Oecol. 1997;18:207–219. doi: 10.1016/S1146-609X(97)80007-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leadley PW, Niklaus P, Stocker R, Körner C. Effects of elevated CO2 on plant species dominance in a highly diverse calcareous grassland. In: Körner C, Bazzaz FA, editor. Carbon Dioxide Populations and Communities. San Diego, USA: Academic Press; 1996. pp. 59–176. [Google Scholar]

- Niklaus PA, Leadley PW, Stöcklin J, Körner C. Nutrient relations in calcareous grassland under elevated CO2. Oecologia. 1998;116:67–75. doi: 10.1007/s004420050564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niklaus PA, Alphei J, Ebersberger D, Kampichler C, Kandeler A, Tscherko D. Six years of ins situ CO2 enrichment evoke changes in soil structure and soil biota of nutrient-poor grass land. Global Change Biology. 2003;9:585–600. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2486.2003.00614.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leadley PW, Niklaus PA, Stocker R, Körner C. A field study of the effects of elevated CO2 on plant biomass and community structure in a calcareous grassland. Oecologia. 1999;118:39–49. doi: 10.1007/s004420050701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh TL, Saxman P, Cole J, Tiedje J. Terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis program, a web-based research tool for microbial community analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:3616–3620. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.8.3616-3620.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team 2004 R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. http://www.R-project.org