Summary

Active and passive characteristics of the canine adductor- abductor muscles were investigated through a series of experiments conducted in vitro. Samples of canine posterior cricoarytenoid muscle (PCA), lateral cricoarytenoid muscle (LCA), and interarytenoid muscle (IA) were dissected from dog larynges excised a few minutes before death and kept in Krebs-Ringer solution at a temperature of 37°C ± 1°C and a pH of 7.4 ± 0.05. Active twitch and tetanic force was obtained in an isometric condition by applying field stimulation to the muscle samples through a pair of parallel-plate platinum electrodes. Force and elongation of the samples were obtained electronically with a dual-servo system (ergometer). The results indicate that the twitch contraction times of the three muscles are very similar, with the average of 32 ± 1.9 ms for PCA, 29 ± 1.6 ms for LCA, and 32 ± 2.4 ms for IA across all elongations. Thus, PCA, LCA, and IA muscles are all faster than the cricothyroid (CT) muscles but slower than the thyroarytenoid (TA) muscles. The tetanic force response times of these muscles are also similar, with a maximum rate of force increase of 0.14 N/ms.

Keywords: Canine larynx, PCA, LCA, Posturing, Laryngeal muscles, Tetanic contraction, Twitch response, Contractile properties

INTRODUCTION

Vocal fold posturing, an essential component of respiration and speech production, is a process that controls the vocal folds length, tension, glottal width, and glottal flow resistance before or during phonation. Contraction of one or more of the five intrinsic laryngeal muscles, the thyroarytenoid (TA), cricothyroid (CT), interarytenoid (IA), posterior cricoarytenoid (PCA), and lateral cricoarytenoid (LCA), is involved. The speed of contraction of these muscles, the level of their activation, and their time-dependent stress-strain relations has a major influence on all aspects of voice production. Of these muscles, CT and TA are primarily involved in length and tension control. TA, LCA, and IA are all adductors, whereas PCA is the sole abductor of the vocal folds.1-4

Models of vocal fold posturing require information on the geometry and structure of the laryngeal cartilages and joints, origin and insertion of laryngeal muscles, and response to neural excitation. In particular, a dynamic (time-dependent) model of posturing depends on the active and passive properties of the aforementioned muscles including contraction times, force-elongation relations, and force-velocity relations.5-8 In addition to modeling, the dynamic and physiological properties of these muscles can lend themselves to clinical evaluation of laryngeal function and a better understanding of interactions among muscle groups.3,9,10

In recent years, new anatomical and geometrical data have emerged on the laryngeal cartilages and muscles, some with electronic caliper techniques,11-13 and some with the most advanced MRI techniques that provide submillimeter accuracy.14,15 These data sets give new hope to accurate biomechanical modeling of laryngeal function. The active and passive properties of two laryngeal muscles, the TA and CT, are well documented.16-25 However, data on active and passive properties of other laryngeal muscles are still scarce. Only the twitch contraction of PCA muscle has been investigated due to its importance as the sole abductor in speech and respiration.17,19,26,27 The muscle twitch is a fundamental unit of contraction from which any tetanic contraction can be derived through the summation of the twitch forces that are separated by a randomized activation delay. This delay is based on means and standard deviation of motor unit firing frequencies as described and modeled by Titze.28 Although the twitch contraction time is accepted as an indicator of a muscle's speed of contraction, the biomechanical models that employ these muscles in vocal fold vibration6 and vocal fold posturing8 are in need of tetanic contraction characteristics. Specifically, the time course and active stress-strain behavior are needed for the constitutive equations. Also, passive properties such as Young's modulus and stress-strain relations are needed to complete the quantification of a muscle model.

The purpose of this study was to quantify the twitch and tetanic contraction times and the passive stress-strain relationship for the PCA, LCA, and IA muscles. A simplified model for the tetanic contraction will be presented. Given the current difficulty of obtaining viable tissue and maintaining this viability in vitro over an hour or so of measurement time, highly selective measurements had to be made on our canine tissue samples. At present, we opted for contraction time and stress-strain relationships, but we were not able to obtain force-velocity relations.

METHODOLOGY

Canine larynges were harvested from other research laboratories. (No animals were sacrificed solely for the purpose of our experiment.) The larynges were excised a few minutes before death and immediately submerged in Krebs solution. This solution was continuously aerated with a mixture of 95% oxygen and 5% carbon dioxide. The pH of the solution was 7.4 ± 0.05, and the temperature was maintained about 37°C with an immersion circulator (Fisher Circulation Model 73). The harvested larynges were brought to our laboratory in medium less than 10 minutes after excision.

Before dissection, the average length of the each sample was measured in situ with a caliper. The length of LCA and PCA muscle samples ranged between 12 to 18 mm, and the length of IA muscle samples ranged from 6 to 10 mm. Dissection of the muscle samples was then started immediately, with the larynx continually submerged in the aerated Krebs solution. Due to the large fanning out of the PCA muscle on the cricoid cartilage, samples from this muscle were then either from the vertical portion or the oblique portion. The LCA samples were taken from either left or right side, opposite the PCA sample side, to retain a piece of arytenoid cartilage on the end of both muscles. Most muscle samples were approximately 4 to 7 mm wide and 3 to 5 mm thick. A piece of cartilage was also retained on the cricoid end. LCA and IA samples were taken from the whole muscle and trimmed to about 4 to 5 mm widths. The cross-sectional area of each sample was calculated from the mass and length after removal from the Krebs chamber and removal of the excess liquid with tissue paper.

Experimental method

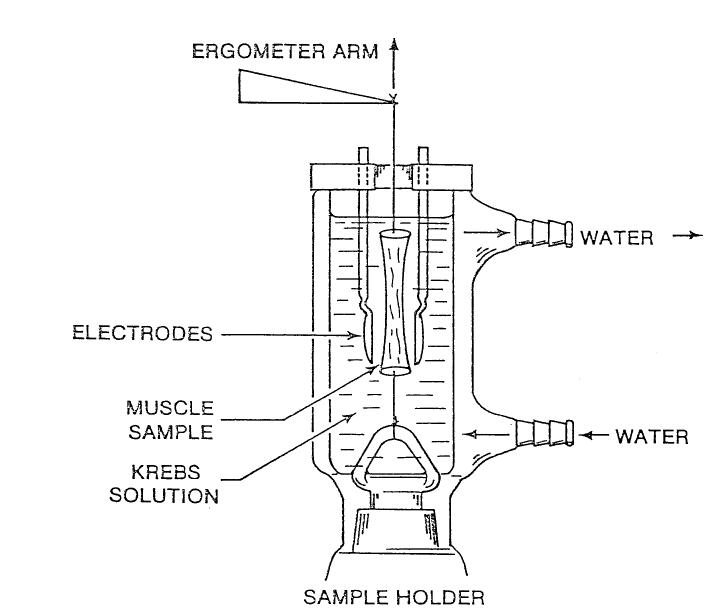

A (4-0) Tevdek polyester suture was inserted through each end piece of cartilage and tied. Using these sutures, one sample was tied to the ergometer arm and one to the bottom of the sample holder (Figure 1). The tension of the suture was adjusted until the sample was mounted with the length close to its in situ length. The tension was typically about 1 to 2 g of force (0.01–0.02 N).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic of sample mounting and the Krebs solution chamber.

The displacement of the ergometer arm and the force exerted by the tissue were measured electronically with a Dual Servo ergometer (Cambridge Technology, Cambridge, Mass). The ergometer had the force resolution of 0.0005 N, displacement accuracy of 0.02 mm, and a rise time of 6 ms. The analog signals of displacement and force of the ergometer were sent to an A/D converter (DI-410, DATAQ Instruments, Akron, Ohio). The two signals were displayed and recorded on the computer at 20 kHz per channel with WINDAQ software (DATAQ Instruments). A pair of parallel-plate electrodes was mounted on the chamber such that the location of electrodes could be adjusted for optimum field stimulation (Figure 1). The stimulation was applied with a Grass S-88 stimulator transverse to the muscle fibers.

For the active properties, each isolated muscle was initially stimulated with a single, brief electrical current (a square pulse) for the twitch contraction; then a train of 70-Hz pulses were applied for 2 seconds to obtain a tetanic response. The tissue sample was allowed to contract in an isometric mode, where the muscle exerts its force against an infinite load (theoretically). In other words, there was not detectable external shortening. The amplitude of the stimulating pulse had to be high enough to depolarize each muscle fiber membrane. As this amplitude was gradually increased, more muscle fibers were depolarized and the peak of the active tension increased until all fibers were activated. Then no further increase was observed in the peak value (ie, saturation had occurred). Increase in the stimulation frequency from 30 Hz to about 90 Hz was tested to reach a fused tetanus, for which ripples in the force response disappear. For most samples, a pulse duration of 1.0 ms, a stimulation frequency of 70 Hz, and a signal strength of 70–90 V yielded the saturated and fused tetanus.

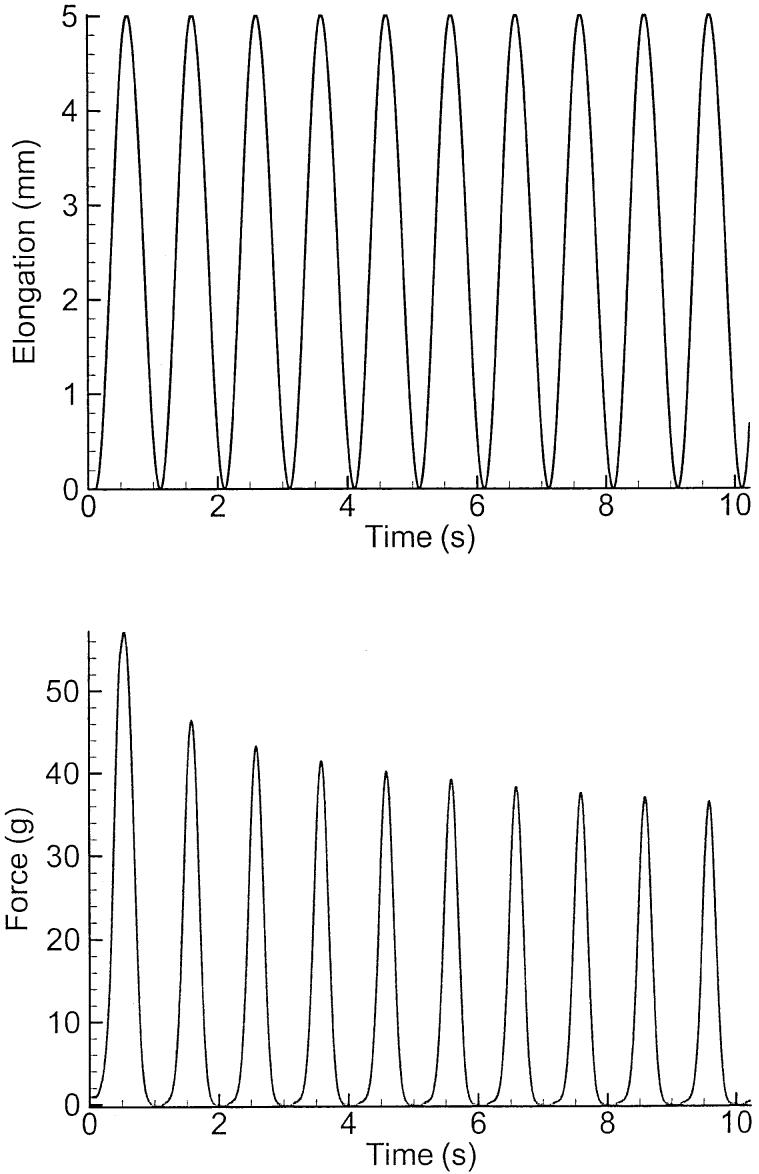

To obtain the passive properties of theses muscles, samples were stretched and released by applying a 1-Hz sinusoidal signal to ergometer as described by Alipour and Titze.23 As this process created some slack in the sutures, application of an initial elongation of 5% helped reduce this slackness. Samples were subjected to about 40% elongation in this manner for about 20 seconds, in which time they showed some relaxation. After about 10 cycles, their force-elongation stabilized to a nonlinear curve from which the passive properties were extracted (see Figure 2). Samples for the passive tissue experiment were not subjected to the tetanic contraction because the long tetanic stimulation may have affected the passive response.22

FIGURE 2.

Force-elongation experiment on a sample of laryngeal muscle. The top graph shows the sample elongation due to the sinusoidal stretch at 1 Hz. The bottom graph shows the force response of the sample measure with ergometer.

RESULTS

Twitch contractile properties

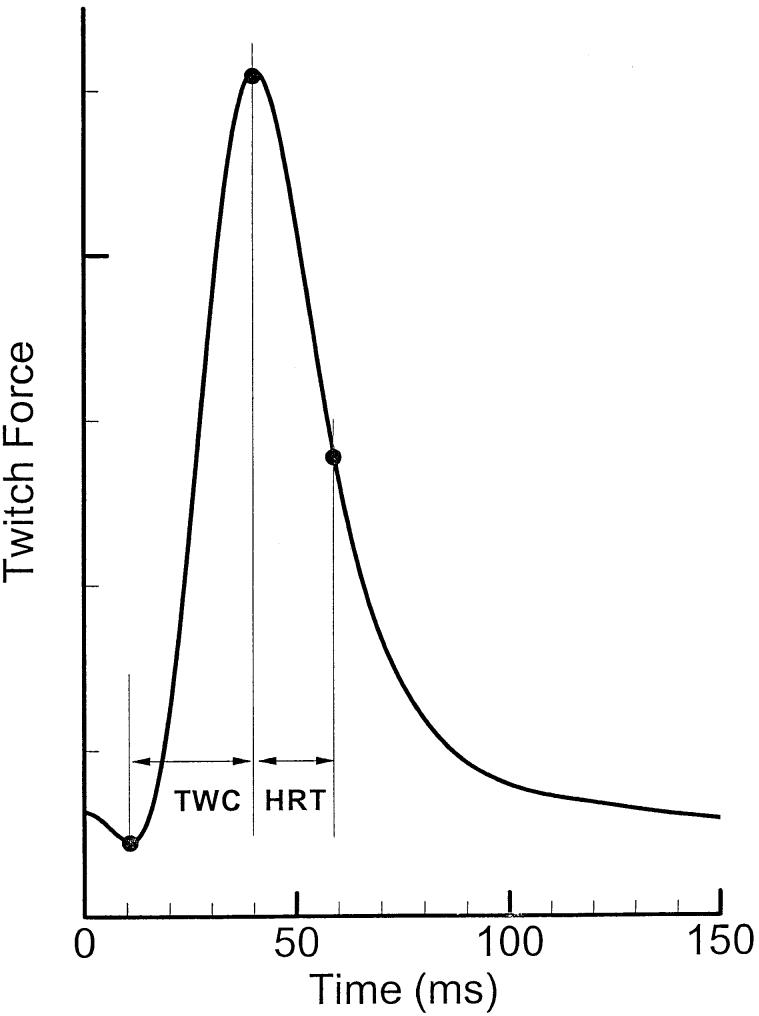

Once the muscle was stimulated with a single pulse, the generated force reached a maximum and then relaxed (Figure 3). The twitch contraction time (TWC) is defined as the time from the start of force rise to its maximum.27 The time required for the muscle to relax to half of its active force is called the half relation time (HRT). These parameters were obtained for all three muscles at different levels of elongation. Together, they describe the time course of a muscle twitch.

FIGURE 3.

A model of a typical twitch force in laryngeal muscles.

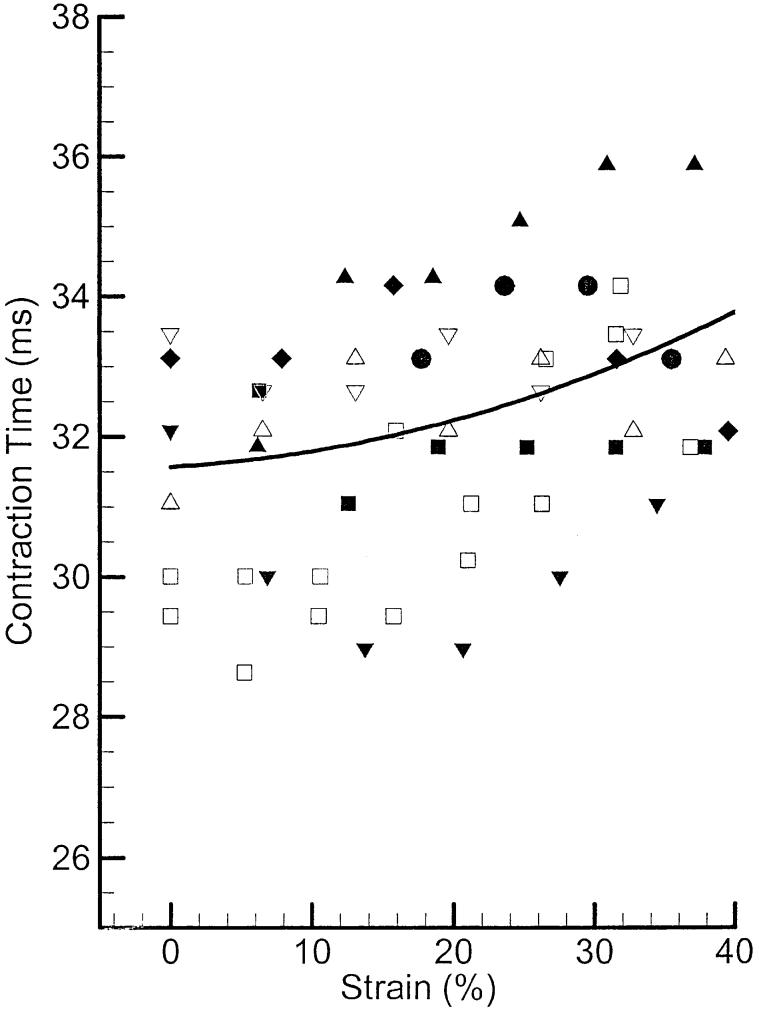

Figure 4 shows contraction times for eight samples of PCA muscle as a function of longitudinal strain. Each symbol represents a separate tissue sample. The mean contraction time across all elongations was 32 ms, with an standard deviation of 1.9 ms. The solid line represents the calculated average between data points by least-square interpolation. There is a slight increasing trend in contraction times with the strain, which makes the contraction time at 40% strain to be approximately 7% larger than at its rest length. This increase of contraction time with elongation was reported for other laryngeal muscles such as TA and CT.21,29

FIGURE 4.

Twitch contraction times of canine PCA muscle. The symbols represent different samples, and the solid line represents the calculated average.

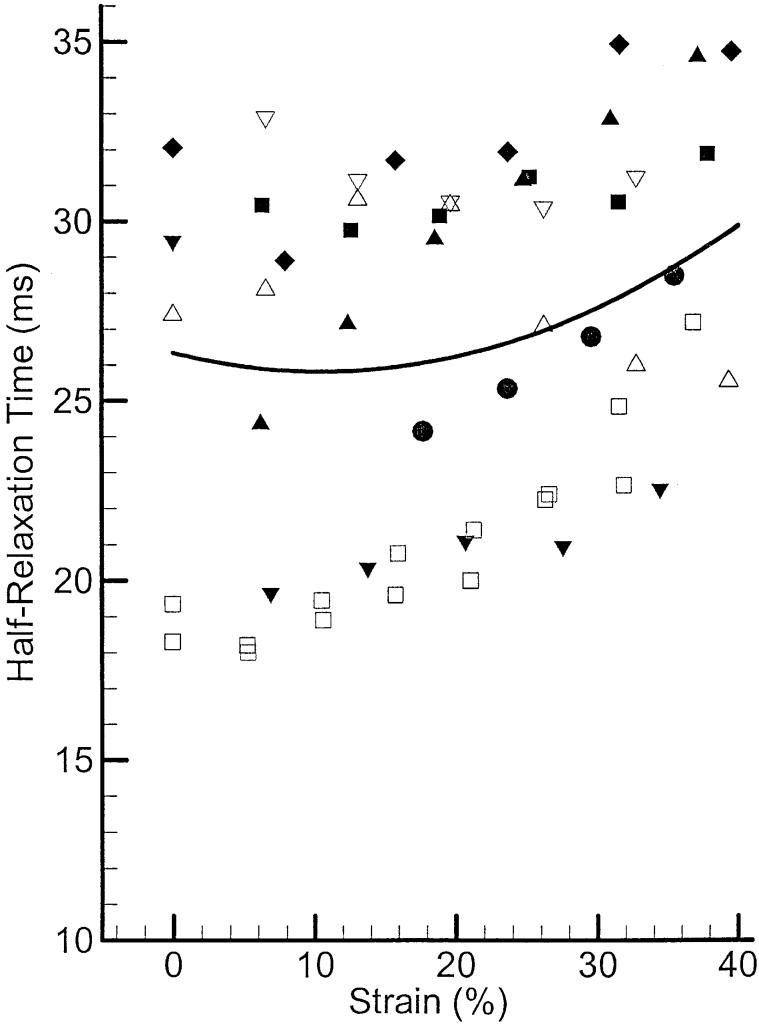

Figure 5 shows half relaxation times for the same eight PCA muscle samples. The mean and standard deviation for this contractile parameter across all elongations are 27 ms and 5.5 ms, respectively. The solid line represents the calculated and smoothed average across samples. There is also an increasing trend with strain, with a 12% increase at the largest strain compared with the rest length. There is more scatter in data points, which is indicated by the higher standard deviation.

FIGURE 5.

Twitch half-relaxation times of canine PCA muscle along with their average.

Table 1 summarizes the mean contraction and half relaxation times for PCA (Vertical and Oblique portions), LCA, and IA muscles at rest length. The contraction times of the two PCA portions are very close, but the half relaxation of the PCAO is 9 ms greater than that of the PCAV. The explanation for this is yet unknown. In all cases, the HRT of a twitch is less than its contraction time (TWC).

TABLE 1.

Twitch Contraction Properties of Posturing Muscles

| Muscle | Samples | Contraction Time (ms) | Half Relaxation Time (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCAV | 3 | 31 ± 2.0 | 21 ± 3.1 |

| PCAO | 5 | 32 ± 0.8 | 29 ± 3.0 |

| LCA | 6 | 30 ± 2.2 | 19 ± 1.3 |

| IA | 5 | 33 ± 2.9 | 24 ± 2.7 |

Tetanic contractile properties

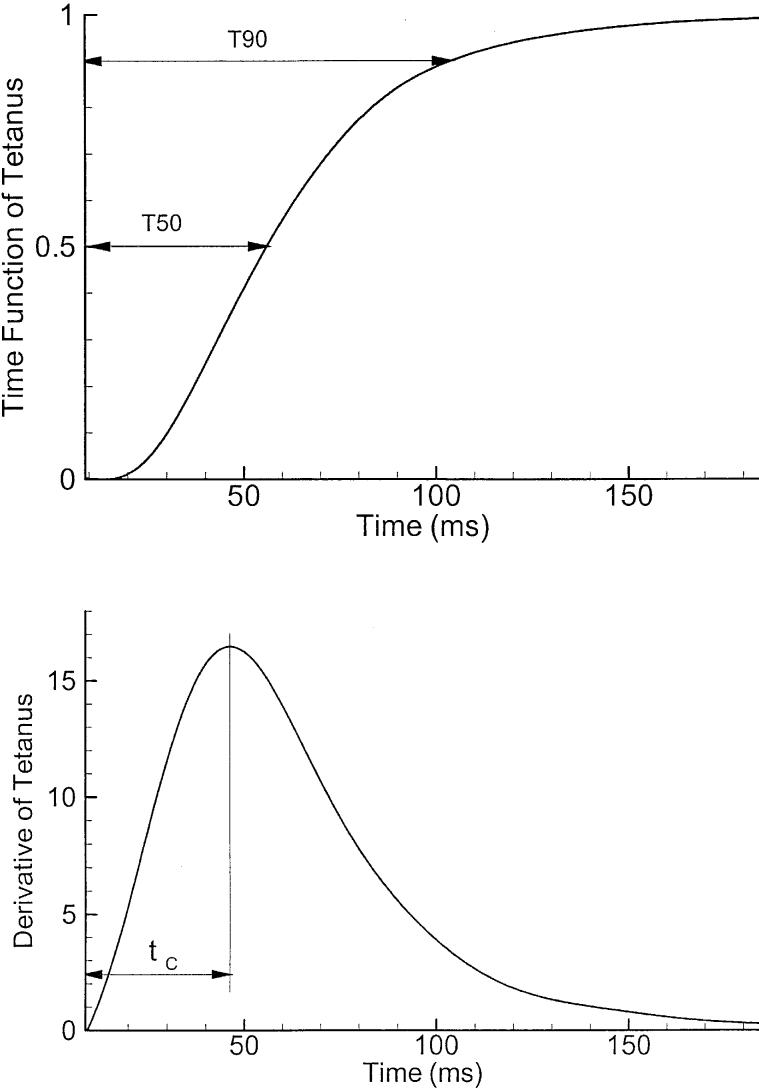

Although the twitch contraction shows how an individual muscle responds to a single pulse of stimulation, and its time course indicates the dynamics of muscle contraction, the typical form of contraction in vocal fold posturing is a tetanus that last a few seconds. Figure 6 shows the development of a tetanic contraction. In the upper graph, the tetanic force is normalized to its maximum. This force function increases from zero at the time of stimulation and asymptotically reaches its maximum. In the lower graph, the time derivative (slope) of the tetanic force is illustrated. It has a similarity to the twitch contraction, but the time constants are different. As there is no standard definition for a tetanic time constant, Alipour and Titze25 modeled these two functions and chose the location of the peak of the derivative as the relevant time constant for tetanic contraction. The model for these functions was presented as:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where σ is the tetanic stress time function, is its time derivative, t is time, and tc is the time constant as shown in Figure 6.

FIGURE 6.

A model for tetanic contraction. The top graph shows the tetanic time function (tetanic force normalized to its maximum). The bottom graph shows the time derivative (slope) of the tetanic function.

Having the knowledge of this tetanic time constant, one can estimate the amount of time required for the muscle to reach its 50% or 90% contraction times (T50 and T90) from simple relation as given by Alipour and Titze.25

| (3) |

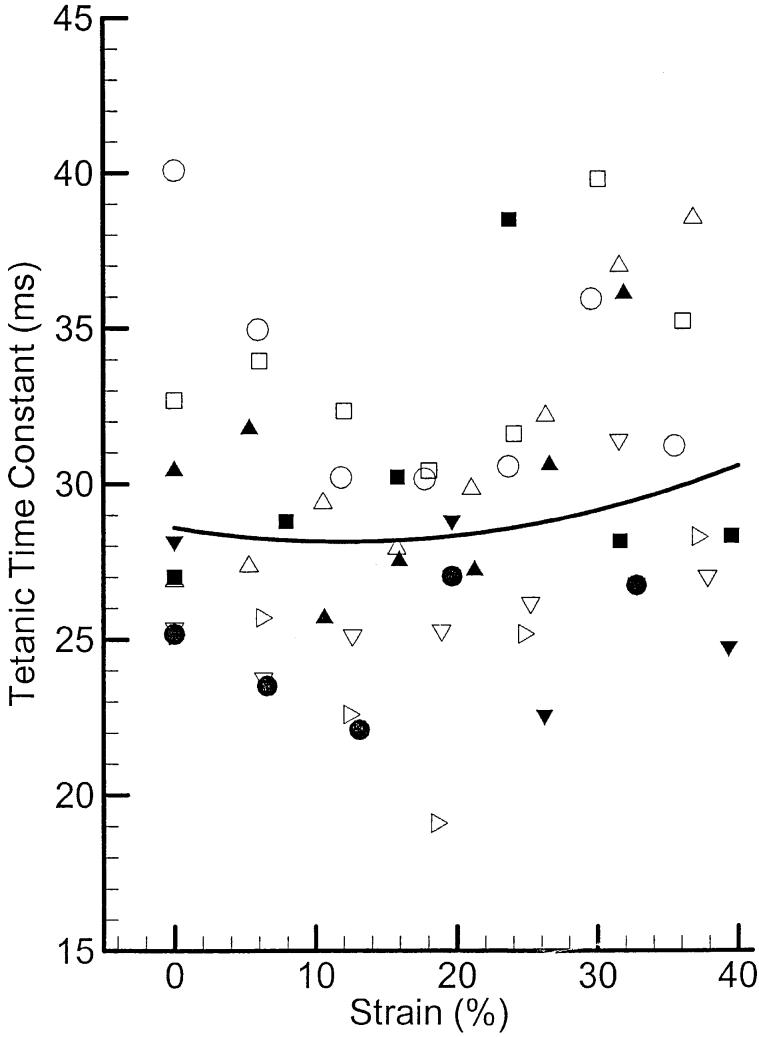

Figure 7 shows the tetanic time constants for nine samples of PCA muscle at various elongation levels. The solid line is the calculated average across all samples. Similar to the twitch contraction time, this tetanic contraction time also shows a small increasing trend with strain (about 7%). The trend may not be considerable in the lower portion of strain axis, but it is more obvious at higher strains.

FIGURE 7.

The tetanic time constant of the canine PCA muscle. The symbols represent different samples, and the solid line represents the calculated average.

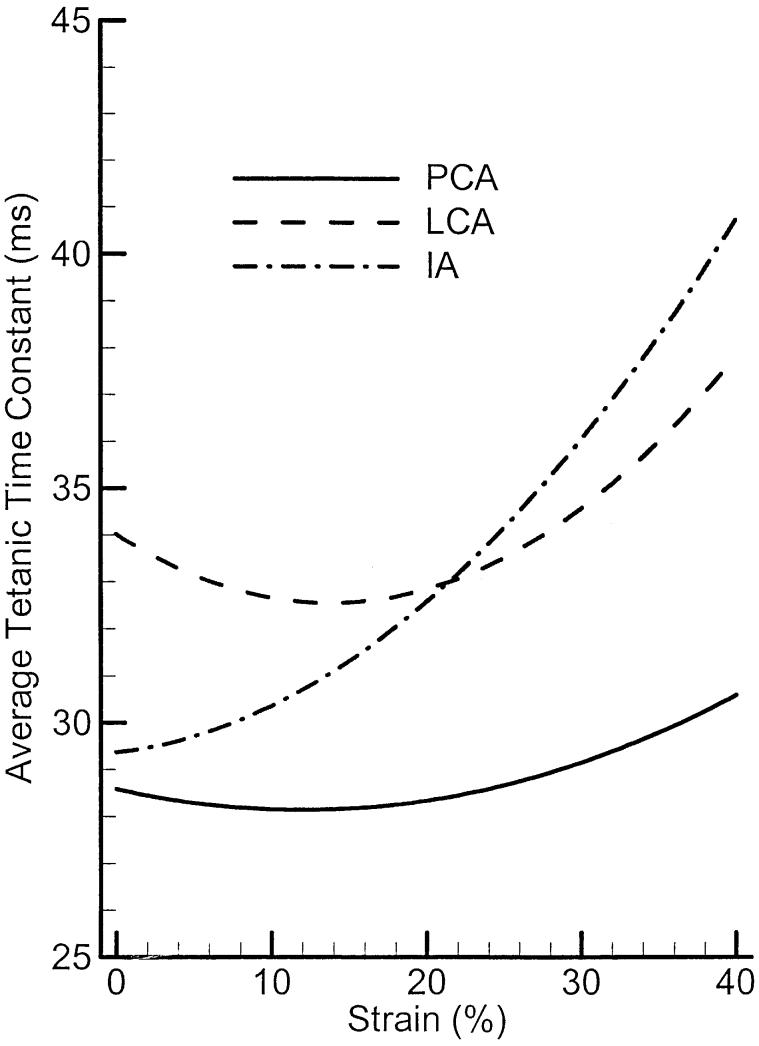

Figure 8 compares the average tetanic time constants of PCA, LCA, and IA muscle for various strains. The LCA muscle has the highest overall values of tetanic times constant (about 4–5 ms higher than PCA) with a small increasing trend in strain. The IA muscle, on the other hand, shows more increases with strain, spanning from 29 to 40 ms (about 38 % increase). Using the relations between this time constant and contraction times T50 and T90 (Equation 3), one can estimate (on the average) how long it would take any of these muscles to reach a specific contraction level. It appears from these average data that PCA is the fastest muscle in the group at all levels of elongation. The IA muscle, which is faster than LCA at smaller strain, becomes slower than LCA at larger strain.

FIGURE 8.

The average tetanic time constants of PCA, LCA, and IA muscles as a function of strain (elongation).

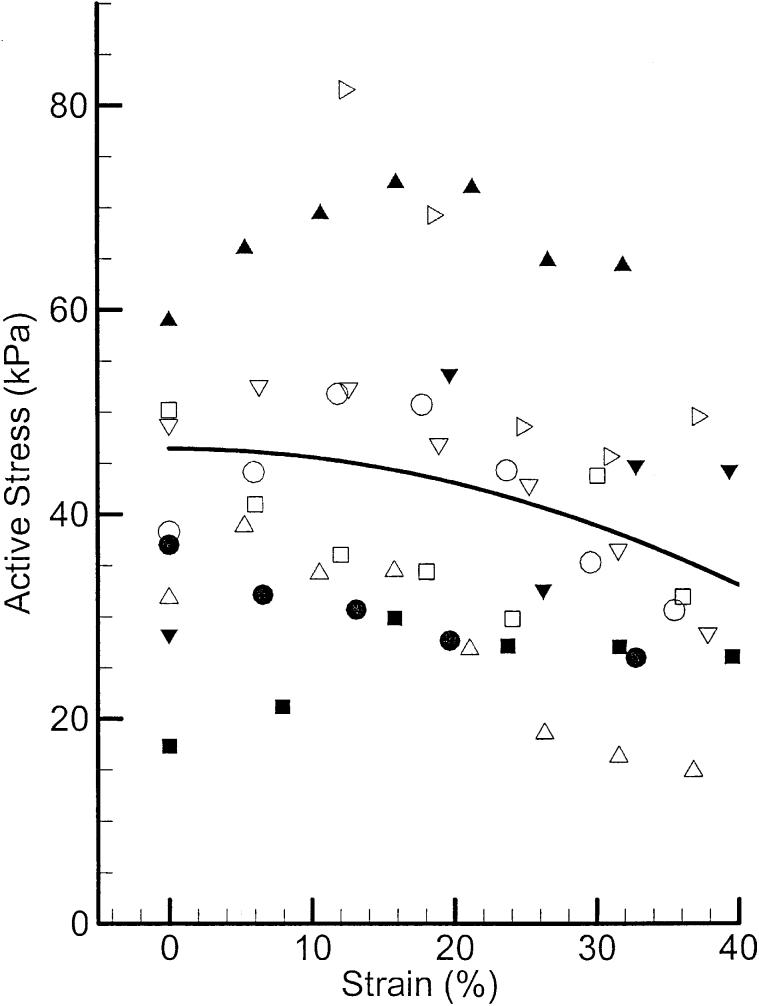

Besides the timing characteristics of these muscles, their force elongation behavior was measured. The tetanic force generated from each sample of the muscle group at various levels of elongation was normalized to its cross-sectional area (calculated from its mass, density, and length). This normalized force, which is called active stress, is shown in Figure 9 for nine samples of PCA muscle. The smoothed average is shown with a solid line. There is a decreasing trend in the active stress, which indicates the optimum sarcomere length of these muscle samples is close to the mounted length (zero strain).

FIGURE 9.

Active stress-strain relations in canine PCA muscle samples along with their averaged data (solid line).

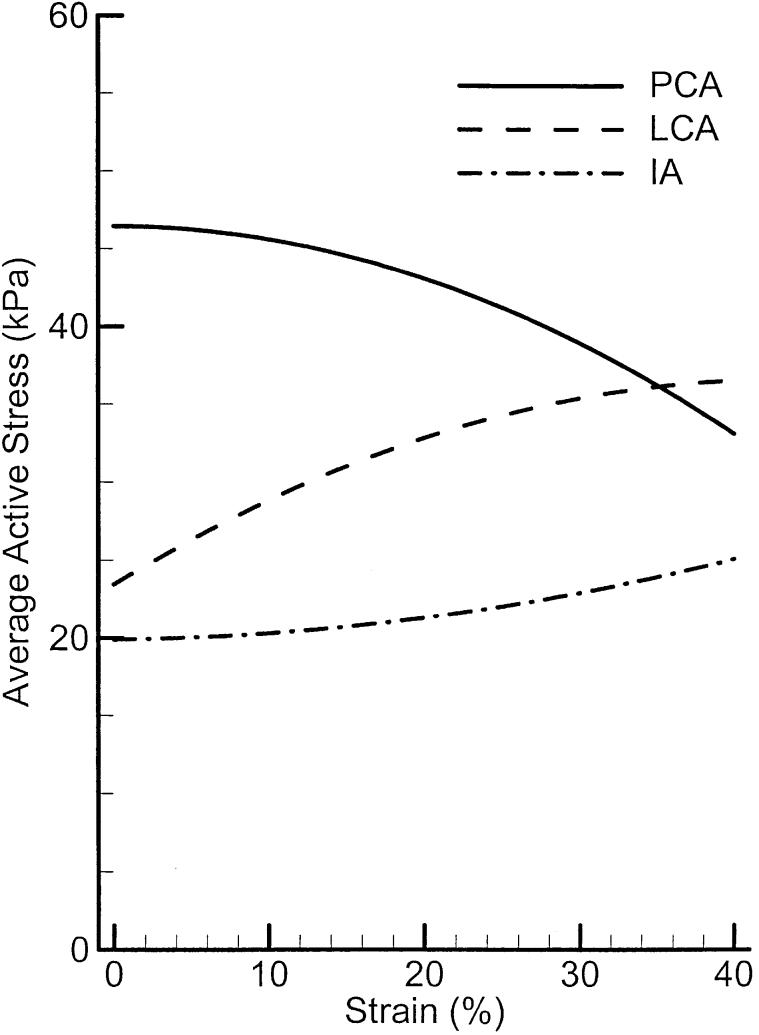

Figure 10 compares the average active stress-strain relations of the three muscle groups. Although PCA shows a decreasing trend, LCA and IA show the increasing trends, which are similar to the cricothyroid muscles.24 Comparing the maximum of these active stresses with the value 100 kPa for TA muscle22 and the value 115 kPa for CT muscle,24 it appears that these adductor/abductor muscles (PCA, LCA, and IA) generate much lower active stress (force per unit area or per fiber) than the TA and CT muscles. This may need further investigation. One possible explanation is that the adductor/abductor muscles are used more for positioning than holding tension. Hence, speed and fine control is more important than strength. Another explanation is that the muscle samples were not as fresh, thus having lost some of their excitability.

FIGURE 10.

Averaged active stress-strain relations of PCA, LCA, and IA muscles.

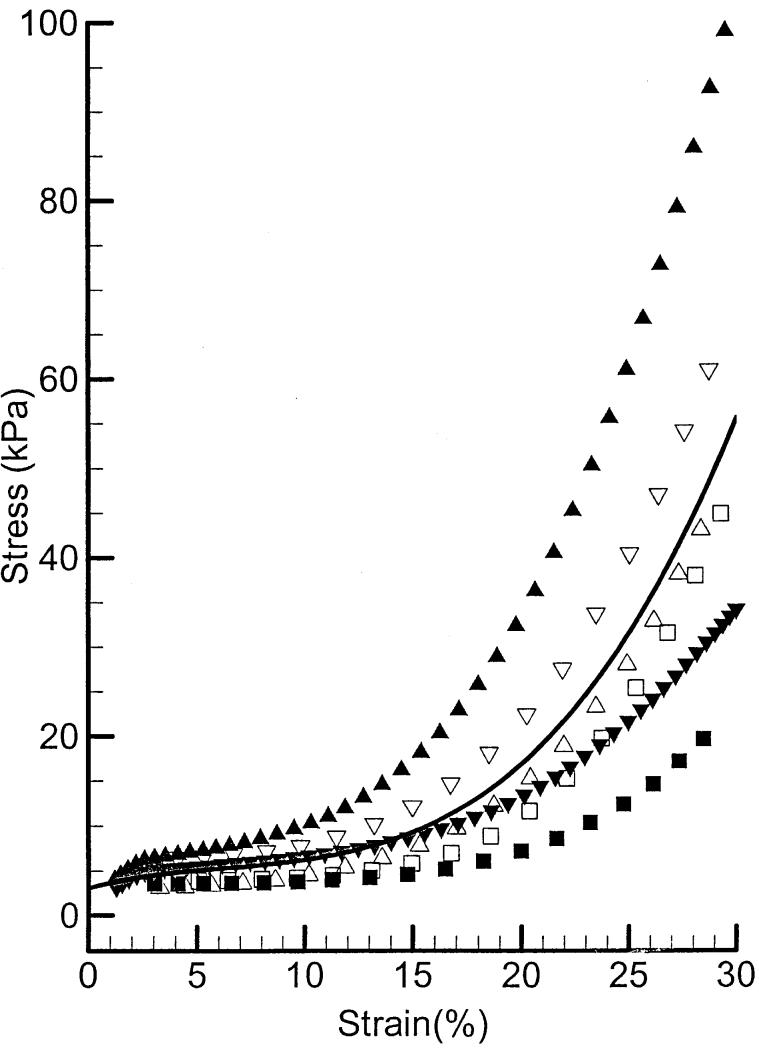

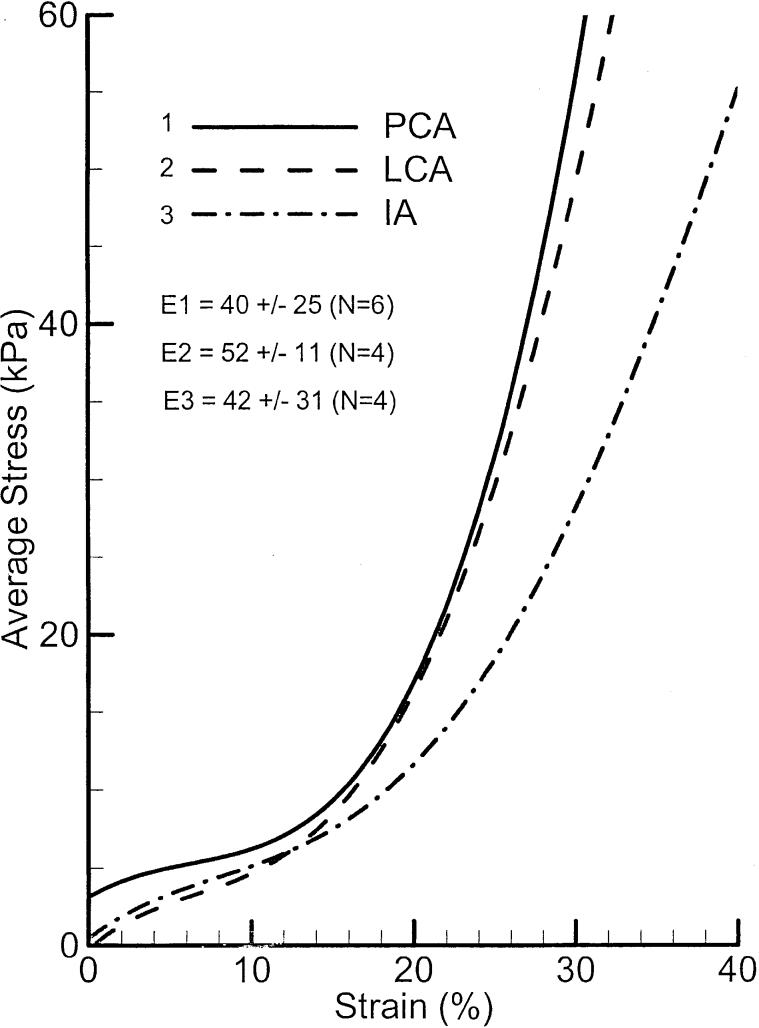

Passive stress-strain relations of six samples of PCA muscle and their average are shown in Figure 11. Each sample shows an initial slow rising (due to elastin fibers), which can be approximated by a linear function to 15% strain. A nonlinear (exponential) rise (due to the collagen fiber) is seen at higher strain. There is a large variability in the passive properties. To compare the passive properties across the three muscles, the average stress-strain relationships for all three are plotted in Figure 12. A Young's modulus for each muscle can be calculated in the low strain range. The mean Young's moduli for the PCA and IA are very close (40 and 42 kPa), but LCA shows a little higher value (52 kPa).

FIGURE 11.

Passive stress-strain relations of samples of canine PCA muscles and their averaged curve (solid line).

FIGURE 12.

Elastic properties of canine PCA, LCA, and IA muscles. The printed values in graphs (E1, E2, and E3) are the mean Young's moduli and standard deviation for low strain.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

This study examined the active and passive properties of laryngeal posturing muscles. The data demonstrated that all three muscles have similar twitch and tetanic contraction times. The twitch contraction time for all PCA samples across all elongations was 32 ± 1.9 ms, which is in agreement with the value of 33 ± 2 ms reported by Cooper et al.27 The tetanic time constants, based on an exponential force development model, are very close to the twitch contraction times. This tetanic time constant can be used to estimate the duration of tetanic contraction to 50% or 90% for each muscle. The rate of tetanic development (measured in N/s) is also not much different, indicating similarity in tetanic force development. Comparison of tetanic time constant of these muscles with time constants of TA and CT muscles25 indicates that these muscles are generally faster than the CT muscle (which has a time constant of 50–65 ms) but slower than the TA muscle (with time constant of 25–30 ms). The calculated 90% contraction time of 110 ms for PCA muscle is in agreement with the duration of a closing gesture reported by Hillel4 using electromyography.

The contraction times of these laryngeal muscles are related to their histochemical compositions. In all muscles there is a mixture of Type I and Type II fibers, although their distributions are not the same in human and primates. It has been shown that a higher percentage of Type II fiber exists in faster muscles.30-33 Based on a histochemical report by Teig et al,30 the order of speed of human laryngeal muscles should be TA (fastest), followed by LCA, IA, CT, and PCA, which is similar to what was reported by Happak et al.31 However, the histochemical data for canine laryngeal muscles are limited. Our twitch contraction data show LCA being faster than PCA and IA within 1–3 ms, but also show PCA is faster than CT, which does not completely agree with human histochemical distribution data.

The comparison of active and passive stress-strain relations shows that these muscles have very similar passive response, but their active force responses are somewhat different. For example, the PCA muscle shows its maximum active stress at low strain values, whereas LCA and IA muscles have their maximum active stress at higher strain. This might be due to the functional agonist–antagonist relation between these muscles. As one increases length, the other decreases length. Hence, keeping their relative strengths comparable over a gesture requires a different starting point with regard to optimum sarcomere length. In previous studies of laryngeal muscles such as TA and CT, their functional difference showed similar effects. The TA muscle had active stress similar to PCA, whereas the CT muscle had active stress similar to LCA and IA.22,24 The CT and TA are also an agonist–antagonist pair.

In conclusion, using the measured tetanic time constant and an exponential force development model, one can simulate tetanic force generation, except for the absolute magnitude. Tetanic contraction of each muscle can be simulated using the knowledge of its tetanic time constant based on Equations 1 through 3. This tetanic model can be used in a biomechanical posturing model, where the time course of individual muscle contraction is the building block of a dynamic posturing model such as Hunter.8 The absolute magnitude of the muscle force can be estimated from its passive and active stress-strain responses and the level of its elongation. Theoretically, by assuming a mean firing rate from EMG signals, the magnitude of the tetanus can be shown to be on the order of five to six times the magnitude of the twitch. Thus, in vivo and in vitro data can be combined to estimate the complete force response of each muscle.

Acknowledgment

We thank Doug Montequin and Roger Chan for assistance in data collection.

Footnotes

Supported by Grant DC004347 from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hirano M, Ohala J, Vennard W. The function of laryngeal muscles in regulating fundamental frequency and intensity of phonation. J Speech Hear Res. 1969;12:616–628. doi: 10.1044/jshr.1203.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirose H. Posterior cricoarytenoid as a speech muscle. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1976;85:335–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi HS, Ye M, Berke GS. Function of the interarytenoid (IA) muscle in phonation: in vivo laryngeal model. Yonsei Med J. 1995;36:58–67. doi: 10.3349/ymj.1995.36.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hillel AD. The study of laryngeal muscle activity in normal human subjects and in patients with laryngeal dystonia using multiple fine-wire electromyography. Laryngoscope. 2001;111(Suppl 97):1–47. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200104001-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farley GR. A biomechanical laryngeal model of voice F0 and glottal width control. J Acoust Soc Am. 1996;100:3794–3812. doi: 10.1121/1.417218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alipour F, Berry DA, Titze IR. A finite element model of vocal fold vibration. J Acoust Soc Am. 2000;108:3003–3012. doi: 10.1121/1.1324678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Titze IR, Story BH. Rules for controlling low-dimensional vocal fold models with muscle activation. J Acoust Soc Am. 2002;112:1064–1076. doi: 10.1121/1.1496080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunter EJ. Three-dimensional biomechanical model of vocal fold posturing. University of Iowa; Iowa City, Iowa: Dec, 2001. Ph.D. dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woodson GE, Picerno R, Yeung D, Hengesteg A. Arytenoid adduction: controlling vertical position. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2000;109:360–364. doi: 10.1177/000348940010900404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baker KK, Ramig LO, Sapir S, Luschei ES, Smith ME. Control of vocal loudness in young and old adults. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2001;44:297–305. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2001/024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mineck CW, Tayama N, Chan R, Titze IR. Three-dimensional anatomic characterization of the canine laryngeal abductor and adductor musculature. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2000;109:505–551. doi: 10.1177/000348940010900512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tayama N, Chan RW, Kaga K, Titze IR. Geometric characterization of the laryngeal cartilage framework for the purpose of biomechanical modeling. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2001;110:1154–1161. doi: 10.1177/000348940111001213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tayama N, Chan RW, Kaga K, Titze IR. Functional definitions of vocal fold geometry for laryngeal biomechanical modeling. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2002;111:83–92. doi: 10.1177/000348940211100114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Selbie WS, Zhang L, Levine WS, Ludlow CL. Using joint geometry to determine the motion of the cricoarytenoid joint. J Acoust Soc Am. 1998;103:1115–1127. doi: 10.1121/1.421223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Selbie WS, Gewalt SL, Ludlow CL. Developing an anatomical model of the human laryngeal cartilages from magnetic resonance imaging. J Acoust Soc Am. 2002;112:1077–1090. doi: 10.1121/1.1501586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hast MH. Mechanical properties of the cricothyroid muscle. Laryngoscope. 1966;76:537–548. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hast MH. Mechanical properties of the vocal fold muscle. Practica Oto-Rhino- Laryngologica. 1967;29:53–56. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirose H, Ushijima T, Kobayashi T, Sawashima M. An experimental study of the contraction properties of the laryngeal muscles in the cat. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1969;78:297–307. doi: 10.1177/000348946907800209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martensson A, Skoglund CR. Contraction properties of intrinsic laryngeal muscles. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1964;60:318–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1964.tb02895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alipour-Haghighi F, Titze IR. Viscoelastic modeling of canine vocalis muscle in relaxation. J Acoust Soc Am. 1985;78:1939–1943. doi: 10.1121/1.392701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alipour-Haghighi F, Titze IR, Durham P. Twitch response in the canine vocalis muscle. J Speech Hear Res. 1987;30:290–294. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3003.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alipour-Haghighi F, Titze IR, Perlman AL. Tetanic contraction in vocal fold muscle. J Speech Hear Res. 1989;32:226–231. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3202.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alipour-Haghighi F, Titze IR. Elastic models of vocal fold tissues. J Acoust Soc Am. 1991;90:1326–1331. doi: 10.1121/1.401924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alipour-Haghighi F, Perlman AL, Titze IR. Tetanic response of the cricothyroid muscle. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1991;100:626–631. doi: 10.1177/000348949110000805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alipour F, Titze I. Active and passive characteristics of the canine cricothyroid muscles. J Voice. 1999;13:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0892-1997(99)80056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sato F, Hisa Y. Mechanical properties of the intrinsic laryngeal muscles and biomechanics of the glottis in the dogs. In: Hirano M, Kirshner JA, Bless DM, editors. Neurolaryngology: Recent Advances. College Hill; Boston, MA: 1987. pp. 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cooper DS, Shindo M, Sinha U, Hast MH, Rice DH. Dynamic properties of the posterior cricoarytenoid muscle. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1994;103:937–944. doi: 10.1177/000348949410301203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Titze IR. A model for neurologic sources of aperiodicity in vocal fold vibration. J Speech Hear Res. 1991;34:460–472. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3403.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perlman AL, Alipour-Haghighi F. Comparative-study of the physiological-properties of the vocalis and cricothyroid muscles. Acta Oto-Laryngologica. 1988;105:372–378. doi: 10.3109/00016488809097021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teig E, Dahl HA, Thorkelson H. Actomyosin ATPase activity of human laryngeal muscles. Acta Otolaryngol (Stokhol) 1978;85:272–281. doi: 10.3109/00016487809111935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Happak W, Zrunek M, Pechmann U, Streinzer W. Comparative histochemistry of human and sheep muscles. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh) 1989;107:283–288. doi: 10.3109/00016488909127510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Claassen H, Werner JA. Fiber differentiation of the human laryngeal muscles using the inhibition reactivation myofibrillar ATPase technique. Anat Embryol. 1992;186:341–346. doi: 10.1007/BF00185983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu YZ, Baker MJ, Crumley RL, Blanks RH, Caiozzo VJ. A new concept in laryngeal muscle: Multiple myosin isoform types in single muscle fibers of the lateral cricoarytenoid. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;118:86–94. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(98)70380-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]