Abstract

Background

Gene-targeted iMycEμ mice that carry a His6-tagged mouse Myc(c-myc)cDNA, MycHis, just 5' of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain enhancer, Eμ, are prone to B cell and plasma cell neoplasms, such as lymphoblastic B-cell lymphoma (LBL) and plasmacytoma (PCT). Cell lines derived from Myc-induced neoplasms of this sort may provide a good model system for the design and testing of new approaches to prevent and treat MYC-driven B cell and plasma cell neoplasms in human beings. To test this hypothesis, we used the LBL-derived cell line, iMycEμ-1, and the newly established PCT-derived cell line, iMycEμ-2, to evaluate the growth inhibitory and death inducing potency of the cancer drug candidate, CDDO-imidazolide (CDDO-Im).

Methods

Morphological features and surface marker expression of iMycEμ-2 cells were evaluated using cytological methods and FACS, respectively. mRNA expression levels of the inserted MycHis and normal Myc genes were determined by allele-specific RT-PCR and qPCR. Myc protein was detected by immunoblotting. Cell cycle progression and apoptosis were analyzed by FACS. The expression of 384 "pathway" genes was assessed with the help of Superarray© cDNA macroarrays and verified, in part, by RT-PCR.

Results

Sub-micromolar concentrations of CDDO-Im caused growth arrest and apoptosis in iMycEμ-1 and iMycEμ-2 cells. CDDO-Im-dependent growth inhibition and apoptosis were associated in both cell lines with the up-regulation of 30 genes involved in apoptosis, cell cycling, NFκB signaling, and stress and toxicity responses. Strongly induced (≥10 fold) were genes encoding caspase 14, heme oxygenase 1 (Hmox1), flavin-containing monooxygenase 4 (Fmo4), and three members of the cytochrome P450 subfamily 2 of mixed-function oxygenases (Cyp2a4, Cyp2b9, Cyp2c29). CDDO-Im-dependent gene induction coincided with a decrease in Myc protein.

Conclusion

Growth arrest and killing of neoplastic mouse B cells and plasma cells by CDDO-Im, a closely related derivative of the synthetic triterpenoid 2-cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1,9-dien-28-oic acid, appears to be caused, in part, by drug-induced stress responses and reduction of Myc.

Background

2-cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1,9-dien-28-oic acid (CDDO) and closely related derivatives, such as CDDO-imidazolide (CDDO-Im) [1], are novel synthetic triterpenoids that exhibit potent in vitro activity against a wide range of human cancers including lung and ovarian carcinoma [2], acute myeloid leukemia [3], cutaneous T-cell lymphoma [3], chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) [4] and multiple myeloma (MM) [5]. CDDO's anti-neoplastic activity involves a complex set of biochemical pathways that can lead, depending on cell type and context, to induction of cell differentiation and apoptosis [3,5-7], inhibition of cell growth and proliferation [2], distortion of redox balance [8], enhancement of TGF-β signaling [9], and suppression of inflammation [10]. The latter can also involve the non-malignant bystander cells of neoplasia, such as macrophages, in which treatment with CDDO results in inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) [11,12]. A newly emerging aspect of tumor inhibition by CDDO with implications for tumor invasion and metastasis is the repression of collagenase [10].

Among CDDO's pleiotropic effects on cancer cells, induction of cell death has received the most attention. Killing of cancer cells by CDDO has been associated with down-regulation of c-FLIP (FLICE inhibitory protein), cleavage of Bid (BH3 interacting death domain agonist), activation of caspases 8 and 3, release of mitochondrial cytochrome c, change in PPAR-γ (proximal proliferator-activated receptor gamma) expression, and inhibition of NFκB (nuclear factor-kappa B) [13-17]. CDDO has been shown to activate extrinsic and intrinsic pathways of caspase-dependent apoptosis. One theory postulates that CDDO-induced production of reactive oxygen species is largely responsible for down regulation of c-FLIP, which results in activation of caspase 8 followed by cleavage of Bid and disruption of mitochondria [13-15]. Activation of Bax (Bcl-2 associated X protein) may enhance this response [6,15]. An alternative theory has linked CDDO-induced cell death to a caspase-independent distortion of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis. According to this view, CDDO causes sustained elevation in cytoplasmic Ca2+, which leads, in turn, to activation of Ca2+-dependent enzymes including apoptosis-mediating endonucleases [18].

B-lineage neoplasms that predictably develop in transgenic mice, such as the iMycEμ [19] and iMycCα [20] gene-insertion strains, may be helpful to elucidate the mechanism by which CDDO-Im inhibits human B cell and plasma cell tumors. To evaluate this possibility, we studied the effects of CDDO-Im in two cell lines, designated iMycEμ-1 and iMycEμ-2. These lines were derived from a lymphoblastic B-cell lymphoma and plasmacytoma, respectively, that arose in two different iMycEμ mice. Strain iMycEμ comprises a model of a certain subset of the human MYC- and mouse Myc-activating t(8;14)(q24;q32) and T(12;15)(Igh-Myc) translocations [19]. Here we show that the CDDO-Im-induced killing of the iMycEμ-1 and-2 cells was associated with both down-regulation of Myc protein and changes in the expression of genes that play important roles in apoptosis, NFκB signaling, and stress and toxicity responses. These results suggested that iMycEμ-derived cell lines provide a good pre-clinical model system for the ongoing evaluation of the potential utility of CDDO-Im in the prevention and treatment of human B cell and plasma cell tumors.

Results

Features of iMycEμcells

Gene-targeted iMycEμ mice contain a single-copy mouse MycHis (c-myc) cDNA that has been inserted in opposite transcriptional orientation (5' to 5') just upstream of the mouse immunoglobulin (Ig) heavy-chain intronic enhancer Eμ. The inserted cDNA also encodes a C-terminal His6 tag, which is useful to distinguish message and protein encoded by MycHis and normal Myc [19]. We have recently shown that heterozygous transgenic iMycEμ mice that carry one mutated and one normal Igh locus are prone to mature B cell and plasma cell neoplasms including IgM+ lymphoblastic B-cell lymphoma (LBL), Bcl-6+ diffuse large B cell lymphoma, and Ig-secreting CD138+ plasmacytoma (PCT) [19]. To study the growth and survival requirements of iMycEμ tumor cells in vitro, we derived a cell line from a LBL, designated iMycEμ-1, and a PCT, designated iMycEμ-2. The features of the iMycEμ-1 cells, which over-express MycHis, as expected, have been described in a previous publication [21]. The features of the iMycEμ-2 cells are described here.

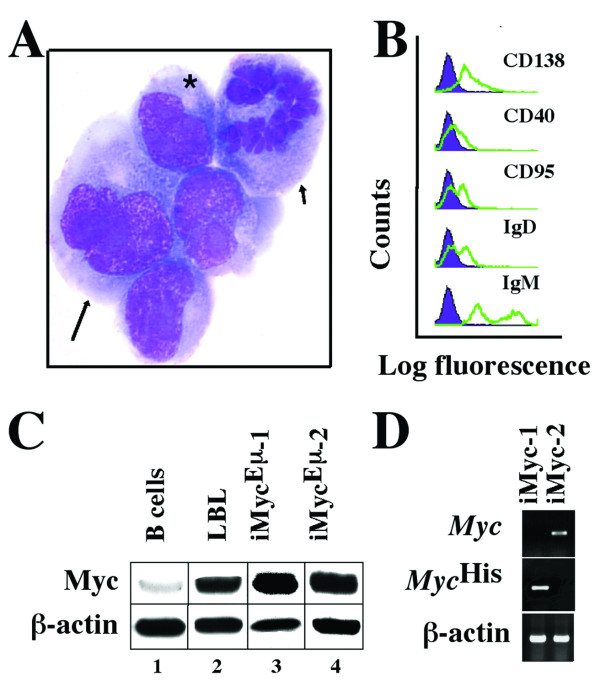

Consistent with their origin from a PCT, the iMycEμ-2 cells exhibited the typical cytological features of aberrant plasmablasts (Fig. 1A). FACS analysis using a panel of antibodies to cell surface markers (Fig. 1B) showed that the iMycEμ-2 cells were positive for CD138 (syndecan 1), whereas CD40, CD90 (Fas) and IgD were detectable at lower levels. Expression of IgM showed a biphasic distribution, a feature that is not uncommon among mouse PCT lines that consist of small lymphoid, predominantly diploid cells (IgMhigh) and large plasmacytoid, predominantly tetraploid and often bi-nucleated cells (IgMlow/-). In agreement with the presence of surface Ig, Southern blotting using JH and Jκ probes revealed rearrangements at the Ig heavy-chain and κ light chain loci (not shown). Western blotting of Myc using antibody that detects both MycHis and normal Myc (Fig. 1C) demonstrated elevated levels of Myc in iMycEμ-2 cells (lane 4), comparable to the levels in iMycEμ-1 cells (lane 3) and a randomly chosen primary LBL (lane 2). In contrast, MACS-purified B220+ splenocytes from young, tumor-free iMycEμ mice, which were included as control (lane 1), contained low amounts of Myc protein. Molecular cytogenetic studies of the iMycEμ-2 cells and the primary tumor from which these cells were derived showed that, during the establishment of the cell line, the iMycEμ-2 cells had changed the mechanism of constitutive Myc expression: in the primary tumor Myc was encoded by the MycHis transgene, whereas in the cell line Myc was encoded by the normal Myc gene, which was deregulated because of a T(12;15)(Igh-Myc) translocation that was not present in the primary tumor [22]. In accordance with this, allele-specific RT-PCR demonstrated that unlike iMycEμ-1 cells, iMycEμ-2 cells expressed normal Myc (Fig. 1D). These studies established that despite their common origin in the same mouse strain, the iMycEμ-1 and-2 cells comprise different types of B cells (LBL versus PCT) that rely on different Myc genes (MycHis versus rearranged, normal Myc) to drive cell growth and proliferation.

Figure 1.

Features of iMycEμ-2 cells. A, Cytofuge specimen stained according to May-Grünwald-Giemsa. A bi-nucleated cell (arrow) and a cell undergoing mitosis (arrowhead) adjoin neoplastic plasmablasts containing the typical paranuclear hof of neoplastic plasmablasts and plasma cells (asterisk). B, B-cell surface marker expression determined by FACS (green lines) compared to isotype controls (purple histograms). C, Western analysis of Myc protein using β-actin as loading control. D, RT-PCR analysis of Myc and MycHis mRNA compared to β-actin message.

CDDO-Im inhibits proliferation and survival of iMycEμ-1 and-2 cells

The anti-proliferative effects of CDDO and CDDO-Im in human cancer cell lines are well documented [2,3,11,16]. To evaluate the potency with which CDDO-Im inhibits the proliferation of mouse iMycEμ-1 and-2 cells, we treated these cells for 24 hrs with a dose range of CDDO-Im and followed up with the MTS assay. Although CDDO-Im caused a significant reduction in the proliferation of both cell lines, the iMycEμ-1 cells were more susceptible than the iMycEμ-2 cells (Fig. 2A). Whereas 500 nM CDDO-Im diminished the growth of iMycEμ-1 cells by 85%, this concentration was only marginally effective in iMycEμ-2 cells. In these cells, growth reduction by ~80% required 5 μM CDDO-Im; i.e., approximately ten times the concentration required for an equivalent reduction in the iMycEμ-1 cells.

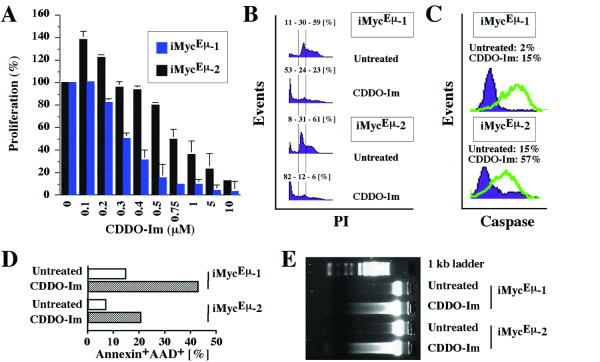

Figure 2.

CDDO-Im-dependent growth arrest and apoptosis in iMycEμ-1 and-2 cells. A, MTS assay of cell proliferation, demonstrating growth inhibition in iMycEμ-1 and-2 cells by ≥200 nM and ≥500 nM CDDO-Im, respectively. Low concentrations of CDDO-Im (100–200 nM) caused growth promotion in iMycEμ-2 cells by an unknown mechanism. B, Cell cycle arrest and increased number of cells with sub-G0/G1 DNA content, as determined by FACS. The percentage values shown above the histograms indicate the fraction of cells with sub-G0/G1, G0/G1 and S/M DNA content, respectively. C, FACS analysis of cells containing activated caspase 3 upon treatment with CDDO-Im (green lines) or left untreated (purple histograms). D, FACS analysis of CDDO-Im treated cells (open columns) and untreated cells (striped columns) undergoing apoptosis based on annexin V and 7-AAD reactivity. E, Fragmentation of genomic DNA detected by electrophoresis in an agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide.

Treatment with CDDO-Im resulted in a net decrease in cell numbers (Fig. 2A), providing indirect evidence that the compound induced cell death. To evaluate this further, we determined cell cycle progression of iMycEμ-1 and-2 cells using flow cytometry. We chose a CDDO-Im dose of 400 nM for the iMycEμ-1 cells and a dose of 1 μM for the iMycEμ-2 cells for this and all subsequent experiments. The exposure time of the cells to the compound, which was also kept constant in all subsequent experiments, was 24 hrs. FACS analysis of propidium iodide-stained cells for cellular DNA content (Fig. 2B) showed a decreased proportion of CDDO-Im-treated cells in the S and G2/M phases of the cell cycle (23% in iMycEμ-1; 6% in iMycEμ-2) compared to untreated cells (59% in iMycEμ-1; 61% in iMycEμ-2). Furthermore, treated samples exhibited an increase in cells with less than diploid DNA content (53% in iMycEμ-1; 82% in iMycEμ-2) relative to controls (11% iMycEμ-1; 8% iMycEμ-2).

Since an increase in the sub-G0/G1 DNA content is usually associated with apoptosis, we used flow cytometry to determine activated caspase 3 (death executioner, Fig. 2C) and annexin V (indicator of apoptosis-associated cell membrane damage, Fig. 2D) in iMycEμ-1 and-2 cells. Treatment of iMycEμ-1 cells with CDDO-Im resulted in a 7.5-fold increase in cleaved caspase-3 reactivity, from 2% to 15%. The increase in iMycEμ-2 cells was 3.8-fold: 15% versus 57% (Fig. 2C). The corresponding elevation in annexin V reactivity (annexin+AAD+) was 2.9-fold (44% versus 15%) in the iMycEμ-1 cells and 3-fold (21% versus 7%) in the iMycEμ-2 cells (Fig. 2D). The annexin+AAD- fraction (incipient apoptosis) and the annexin-AAD+ fraction (dead cells) displayed similar CDDO-Im-induced increases (not shown). These results were confirmed by fractionating genomic DNA on ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels, which demonstrated the typical nucleosomal DNA ladder in cells treated with CDDO-Im, but not in untreated cells (Fig. 2E).

CDDO-Im causes loss of Myc in iMycEμ-1 and-2 cells

Because Myc is crucial for growth and proliferation of normal and malignant B cells in humans and mice [23], we evaluated whether Myc expression in iMycEμ tumor cells might be negatively affected by CDDO-Im. We treated both cell lines with the compound followed by preparation of cell lysates and Western blotting for Myc, using antibody that detects both MycHis and normal Myc (Fig. 3A top). Comparison of Myc and β-actin, which was included to ascertain equal protein loading, showed that CDDO-Im reduced Myc expression in both cell lines; by a factor of ~3 in iMycEμ-1 and ~5 in iMycEμ-2. To determine whether down regulation of Myc protein was associated with a drop in Myc message, we performed allele-specific RT-PCR of MycHis and Myc mRNA. Treatment with CDDO-Im resulted in a reduction of Myc transcripts in iMycEμ-2 cells but did not affect MycHis levels in iMycEμ-1 cells (Fig. 3A bottom). In contrast, the small amount of Myc mRNA present in iMycEμ-1 cells was abrogated by CDDO-Im.

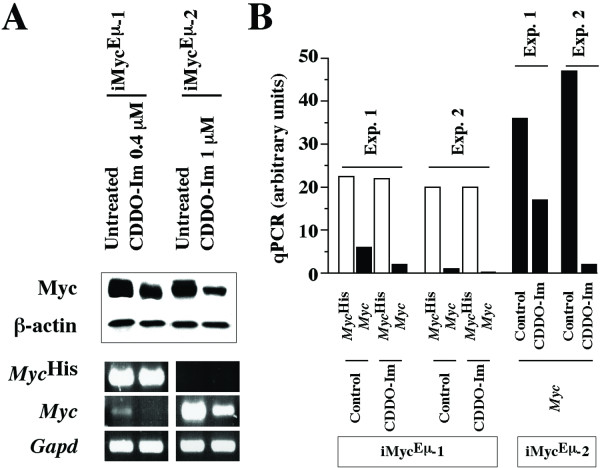

Figure 3.

CDDO-Im-dependent abrogation of NFκB in iMycEμ-1cells and reduction of Myc in iMycEμ-1 and-2 cells. A, Determination of Myc protein using Western analysis (upper panel) and determination of MycHis, Myc, and Gapd mRNA using allele-specific RT-PCR (lower panel). B, Measurement of MycHis and Myc mRNA using allele-specific qPCR.

These results were further validated by two independent qPCR analyses that used allele-specific primers to distinguish MycHis and Myc in the case of the iMycEμ-1 cells (Fig. 3B left), but only Myc primers in the case of the iMycEμ-1 cells (Fig. 3B right). Consistent with the results in Fig. 3A, the MycHis levels (white columns) in the iMycEμ-1 cells were largely unchanged upon treatment with CDDO-Im, whereas the Myc levels (black columns) exhibited a significant reduction. Furthermore, the Myc levels in the iMycEμ-2 cells dropped sharply after exposure to CDDO-Im. These findings indicated that CDDO-Im suppresses Myc protein levels by a post-transcriptional mechanism in the iMycEμ-1 cells, but a more complicated mechanism that involves transcriptional and post-transcriptional changes in the iMycEμ-2 cells. Regardless of the precise molecular mechanisms, the reduction in Myc may be an important principle by which CDDO-Im inhibits iMycEμ tumor cells.

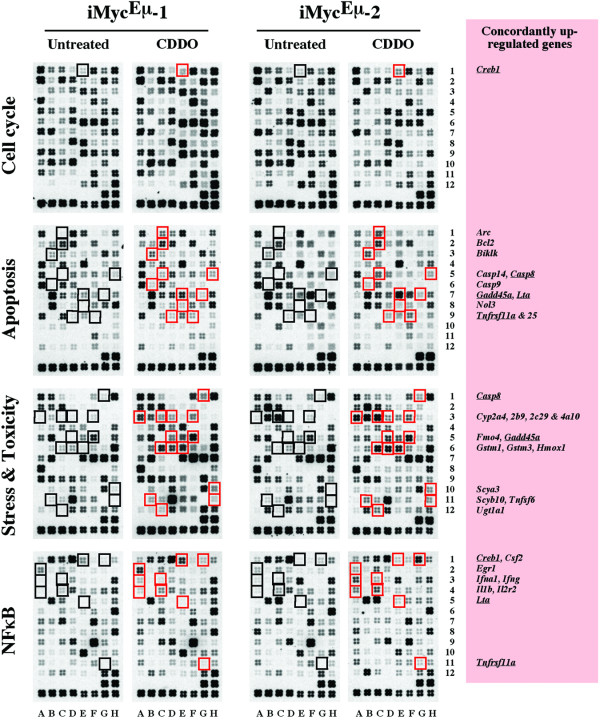

CDDO-Im upregulates 30 genes in iMycEμ-1 and-2 cells

cDNA macroarrays on nylon filter membranes provide a useful screening tool to evaluate the expression of selected pathway genes in mouse cancer cells. To that end, we prepared RNA from iMycEμ-1 and-2 cells that were either treated with CDDO-Im or left untreated (control). RNA samples were reverse transcribed in the presence of 32P-dUTP and hybridized to the gene arrays. This was followed by the determination of the individual gene expression levels and the effects of treatment with CDDO-Im. All samples were evaluated on four different arrays, each containing 96 genes involved in cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, stress and toxicity responses, and NFκB signaling. These arrays were selected because previous work indicated that CDDO-Im can cause growth inhibition (cell cycle array) [2,11,16], cell killing (apoptosis array) [3,4,6,7,13-18], anti-inflammatory effects (NFκB array) [11,12,24] and redox imbalance (stress and toxicity array) [8].

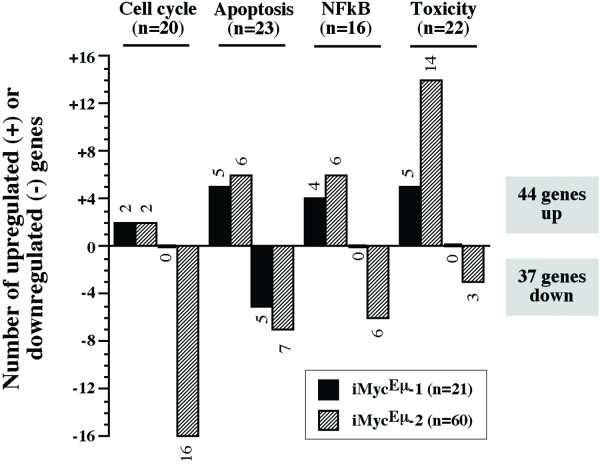

Using stringent criteria for array analysis (≥2-fold expression change reproduced on three or more arrays), we identified a total of 81 differentially expressed genes that were discordantly regulated in CDDO-Im-treated iMycEμ-1 and-2 cells. The genes were either up or down in either one of the cell lines, but unchanged in the other line (Additional File 1). The distribution of these genes among the four arrays is depicted in Fig. 4. In iMycEμ-1 cells, 16 genes were up and 5 genes were down. In iMycEμ-2 cells, 28 genes were up and 32 genes were down. Thus, the iMycEμ-2 cells responded to CDDO-Im treatment with approximately three times as many changes (60 genes) than the iMycEμ-1 cells did (21 genes). The distribution of the differentially expressed genes among the four arrays was even: 20 (25%) in the cell cycle array, 23 (28%) in the apoptosis array, 16 (20%) in the NFκB array, and 22 (27%) in the stress and toxicity array. Up-regulated genes (44/81, 54%) slightly outnumbered down-regulated genes (37/81, 46%). In agreement with the RT-PCR and qPCR data presented in Fig. 3, Myc was suppressed by CDDO-Im on the cDNA arrays in the iMycEμ-2 but not the iMycEμ-1 cells.

Figure 4.

Number of differentially expressed genes in iMycEμ-1 and-2 cells upon treatment with CDDO-Im. Plotted is the overall result of the gene expression analysis using the four cDNA arrays presented in Figure 5. See Additional File 1 for details.

CDDO-Im-induced gene expression changes that occurred concordantly in both cell lines were limited to 30 genes. Interestingly, all of these were up-regulated. They are listed in Table 1 and their location on the array membranes is indicated in Figure 5. Five of 30 genes (underlined in Fig. 5 right) were present on two different arrays, adding confidence to the analysis: Casp8, Creb1, Gadd45a, Lta and Tnfrsf11a. Six of 30 genes exhibited a 10-fold or higher increase upon exposure of cells to CDDO-Im. Three of these belonged to the subfamily 2 of cytochrome P450 mixed function oxygenases (Cyp2a5, Cyp2b9, Cyp2c29) and the other three encoded flavin-containing monooxygenase 4 (Fmo4), heme oxygenase 1 (Hmox1) and caspase 14 (Casp14), respectively. To verify these observations with an independent method, we performed RT-PCR using the primer pairs and reaction conditions listed in Additional File 2. The CDDO-Im-dependent elevation of all six genes was readily confirmed (Fig. 6).

Table 1.

Concordantly up-regulated genes upon treatment with CDDO-Im

| Gene symbol | Gene name | Gene function | Cell line | Array1 | Pos.2 | |

| iMyc-1 | iMyc-2 | |||||

| Arc | activity regulated cytoskeletal-associated protein | CARD family | 2.4 | 47 | Apo | C1 |

| Bcl2 | B-cell leukemia/lymphoma 2 | Bcl2 family | 2.2 | 2.9 | Apo | C2 |

| Biklk | Bcl2-interacting killer-like (Bik) | Bcl2 family | 2.4 | 2.0 | Apo | B3 |

| Casp8 | caspase 8 | caspase family | 5.5 | 4.6 | Apo | H5 |

| Tox | G1 | |||||

| Casp9 | caspase 9 | caspase family | 10 | 6.5 | Apo | B6 |

| Casp14 | caspase 14 | caspase family | 15 | 23 | Apo | C5 |

| Creb1 | cAMP responsive element binding protein 1 | transcription factor | 2.1 | 2.8 | Cycle | E1 |

| NFκB | E1 | |||||

| Csf2 | colony stimulating factor 2 | cytokine | 3.4 | 5.9 | NFκB | G1 |

| Cyp2a4 | cytochrome P450, family 2, subfamily a, polypeptide 5 | oxidative/metabolic stress | 25 | 20 | Tox | A3 |

| Cyp2b9 | cytochrome P450, family 2, subfamily b, polypeptide 9 | oxidative/metabolic stress | 14 | 14 | Tox | C3 |

| Cyp2c29 | cytochrome P450, family 2, subfamily c, polypeptide 29 | oxidative/metabolic stress | 14 | 434 | Tox | D3 |

| Cyp4a10 | cytochrome P450, family 4, subfamily a, polypeptide 10 | oxidative/metabolic stress | 4.9 | 4.5 | Tox | F3 |

| Egr1 | early growth response 1 | oxidative/metabolic stress | 2.5 | 3.9 | NFκB | A2 |

| Fmo4 | flavin containing monooxygenase 4 | oxidative/metabolic stress | 286 | 145 | Tox | D5 |

| Gadd45a | growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible 45 alpha | ATM/p53 pathway | 2.4 | 2 | Apo | E7 |

| Tox | F5 | |||||

| Gstm1 | glutathione S-transferase, mu 1 | oxidative/metabolic stress | 4.4 | 16 | Tox | C6 |

| Gstm3 | glutathione S-transferase, mu 3 | oxidative/metabolic stress | 2.4 | 3.3 | Tox | D6 |

| Hmox1 | heme oxygenase (decycling) 1 | oxidative/metabolic stress | 10 | 12 | Tox | E6 |

| Ifna1 | interferon alpha family, gene 1 | cytokine | 4.9 | 7.9 | NFκB | A3 |

| Ifng | interferon gamma | inflammation | 2.0 | 2.8 | NFκB | C3 |

| Il1b | interleukin 1 beta | inflammation | 4.0 | 11 | NFκB | A4 |

| Il1r2 | interleukin 1 receptor, type II | inflammation | 2.1 | 2.0 | NFκB | C4 |

| Lta | lymphotoxin A | TNF ligand family | 4.1 | 65 | Apo | G7 |

| NFκB | E5 | |||||

| Nol3 | nucleolar protein 3 (apoptosis repressor with CARD domain) | apoptosis/necrosis | 64 | 8.4 | Apo | E8 |

| Scya3 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 3 (Mip-1 alpha) | inflammation | 5.5 | 25 | Tox | H10 |

| Scyb10 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 | inflammation | 2.7 | 4.3 | Tox | B11 |

| Tnfrsf11a | tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 11a (RANK) | TNF ligand family | 2.7 | 102 | Apo | D9 |

| NFκB | G11 | |||||

| Tnfrsf25 | tumor necrosis factor (ligand) superfamily, member 6 (CD178, CD95L, Fasl, gld) | apoptosis/necrosis | 9.6 | 37 | Apo | F9 |

| Tnfsf6 | tumor necrosis factor (ligand) superfamily, member 6 | TNF ligand family | 12 | 8.2 | Tox | H11 |

| Ugt1a1 | UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1 family, member 1 | DNA damage/repair | 4.6 | 6.8 | Tox | C12 |

1GEArray Q series mouse cDNA gene arrays (SuperArray Bioscience Corporation, Gaithersburg, MD) included the MM-001 cell cycle array (Cycle), MM-002 apoptosis array (Apo), MM-012 stress and toxicity array (Tox) and MM-016 NFκB signaling array (NFκB).

2Array position, as indicated in Figure 3

Figure 5.

CDDO-Im-induced up-regulation of genes in both iMycEμ-1 and-2 cells. Shown are cDNA arrays containing 96 genes involved in cell cycling (top row), apoptosis (2nd row), stress and toxicity responses (3rd row) and NFκB signaling (bottom row). CDDO-Im-treated and untreated samples are presented as pairs. Indicated by red squares are CDDO-Im-induced genes. The corresponding controls are indicated by black squares to the left. Gene designations are given in the pink text box on the right. Underlined genes were confirmed on two different arrays. Compare Table 1 for additional details.

Figure 6.

Verification of gene array results using RT-PCR. Shown are ethidium bromide-stained PCR fragments of six different genes found to be up-regulated 10-fold or more in CDDO-Im-treated iMycEμ-1 and-2 cells. The iMycEμ-1 and-2 cells had been treated for 24 hrs with 0.4 μM and 1 μM CDDO-Im, respectively. The fragments were compared to those detected in untreated cells using the same assay conditions. See Table 1 for further details and Additional File 2 for PCR primers and reaction conditions.

cDNA microarray analysis reveals additional gene expression changes

The Mouse Lymphochip, a microarray of hematopoietic mouse cDNA clones, provides a tool for extending the above findings at the level of global gene expression [25]. To evaluate the CDDO-Im-dependent changes in the iMycEμ cell lines, RNA was obtained from treated and untreated cells, labeled with Cy5-dUTP, and hybridized to the cDNA microarray. An RNA control pool labeled with Cy3-dUTP was co-hybridized to the same array and used as a common denominator by which all samples were compared to one another. Further information on microarray make-up and data interpretation is available on-line [26].

The analysis of three independent RNA samples of iMycEμ-1 and-2 cells revealed two additional genes (not present on the Superarrays) that were concordantly up-regulated upon treatment with CDDO-Im:Hck (hemopoietic cell kinase) and Spp1 (secreted phosphoprotein 1). It further uncovered five genes that were concordantly down regulated: Akt2 (thymoma viral proto-oncogene 2), Bat2 (HLA-B associated transcript 2), Pim1 (proviral integration site 1), Psmb9 (proteosome subunit, beta type 9) and Sdc1 (syndecan 1). One of these genes (Akt2) was included (and also found to be reduced) on the Superarrays, but it failed to reach the confidence criteria for significant change. While a more detailed analysis of the microarray results will be presented in a future publication, these results further strengthened the contention that CDDO-Im causes numerous gene expression changes, up and down, in the iMycEμ-1 and-2 cells.

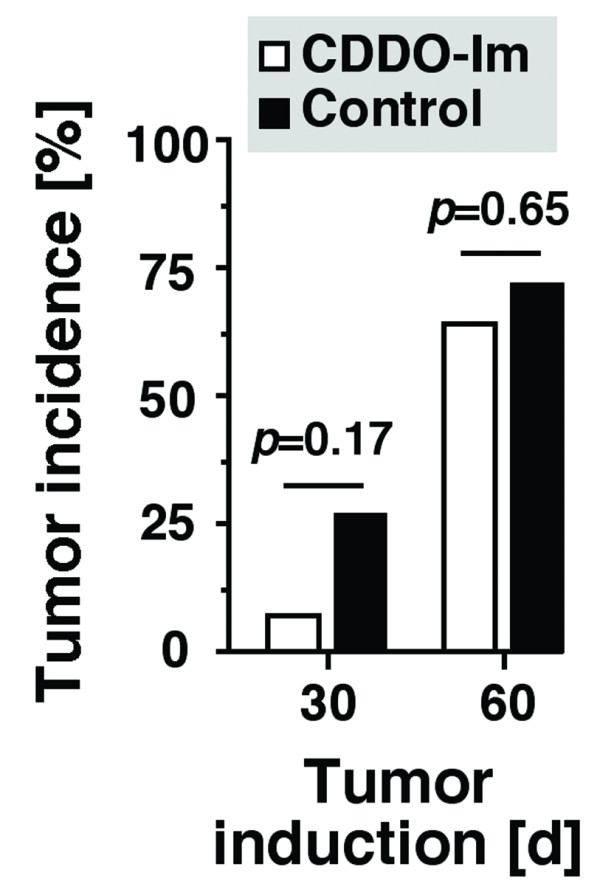

CDDO-Im decelerates pristane-induced plasmacytomas in iMycEμ mice

The growth inhibiting effects of CDDO-Im in the cell lines indicated that this compound might also inhibit de novo development of Myc-driven B cell and plasma cell tumors in vivo. To evaluate this, we primed congenic BALB/c.iMycEμ mice with a single i.p. injection of 0.2 ml pristane to undergo inflammation-dependent plasmacytomagenesis in the peritoneal cavity [27]. While only 1 of 14 mice (7.14%) treated with CDDO-Im developed PCT by day 30 of tumor induction, 3 of 11 mice (27.3%) treated with the vehicle control harbored these tumors (Fig. 7 left). A small CDDO-Im-dependent reduction in tumor incidence was also observed on day 60 post tumor induction: 9/14 (64.3%) mice in the CDDO-Im group versus 8/11 (72.3%) mice in the control group (Fig. 7 right). Although none of these differences was statistically significant, owing in large part to the small study groups in this pilot experiment, the apparent deceleration of PCT on day 30 post-pristane suggested that CDDO-Im inhibits tumor development in vivo.

Figure 7.

CDDO-Im inhibits peritoneal plasmacytomas in iMycEμ gene-insertion mice. Mice were injected i.p. on day 1 with 0.2 ml pristane and either treated with CDDO-Im (100 μg per 50-μl i.p. injection, n = 14) or vehicle control (50 μl PEG 400, n = 11). Treatment commenced on day 7 and continued three times per week throughout the observation period (60 days). The diagnosis of plasmacytoma was established on days 30 and 60 post pristane, using stained ascites cell specimens. Tumor incidence was compared using χ2 analysis, the results of which (probability values, p) are indicated above the columns.

Discussion

This study has demonstrated that CDDO-Im causes growth arrest and apoptosis in the Myc-induced mouse B lymphoma and plasmacytoma cell lines, iMycEμ-1 and iMycEμ-2. As reported by other investigators for human cancer cell lines, cell killing by CDDO-Im, which is generally more potent than the parental compound CDDO [12], was fast (within 24 h) and efficient (at sub-micromolar concentrations). CDDO-Im-induced apoptosis coincided with a decrease in Myc protein levels and a striking induction of the transcription of genes that are involved in drug metabolism and oxidative stress responses. These genes included Hmox1 (heme oxygenase 1), Fmo4 (flavin-containing monooxygenase 4) and three representatives of the cytochrome P450 subfamily 2 of mixed-function oxygenases: Cyp2a4, Cyp2b9 and Cyp2c29.

The 10 to 12-fold elevation of Hmox1 in CDDO-Im-treated iMycEμ cells was consistent with previous reports on the induction of this mouse gene under conditions of chronic [28] or acute oxidative stress [29] and the up-regulation of human HMOX1 by oxidative stress [30,31]. Our finding was also in agreement with a recent study showing that CDDO-Im induces oxidative stress in the neoplastic plasma cells that comprise human MM [8]. In MM, CDDO-Im treatment led to the depletion of glutathione, increased production of reactive oxygen species, and reduction in mitochondrial membrane potential, all indications of heightened oxidative stress. Co-treatment of MM cells with reducing agents, such as N-acetyl-L-cysteine and catalase, alleviated CDDO-Im-dependent oxidative stress, coincident with the elevation of FLICE (Fas-associated death domain-like interleukin-1-converting enzyme) and inhibition of caspase-8 activation [8]. Additional study is warranted to decide whether CDDO-Im-mediated killing of mouse iMycEμ tumor cells relies on a mechanism similar to that operating in human MM.

Unlike induction of cytochrome P450 genes, which is common in drug-exposed cells, the more than 100-fold elevation in Fmo4 message in CDDO-Im-treated iMycEμ cells was surprising, because the flavin-containing monooxygenase family of genes in humans, including FMO4, is widely believed to be un-inducible by drugs. Flavin-containing monooxygenase (FMO) proteins are NADPH-dependent microsomal enzymes that catalyze the oxygenation of compounds containing nucleophilic heteroatoms (N-, S-, P- and others) using two-electron transfer chemistry [32]. The broad substrate specificity of FMOs, whose involvement in the metabolism of xenobiotics is increasingly recognized [33], suggests that CDDO-Im might be a substrate of the FMO pathway. More work is required to elucidate the molecular mechanism by which Fmo4 is over-expressed in CDDO-Im-treated iMycEμ tumor cells and by which Fmo4 might contribute to the catabolism of this compound.

CDDO-Im-treated iMycEμ cells contained elevated levels of mRNA encoding caspase 14, an obscure member of the caspase family of proteins. Casp14 was up-regulated 15-fold in iMycEμ-1 cells and 23-fold in iMycEμ-2 cells. Little is known about circumstances that lead to increased Casp14 expression in mice. Consistent with a possible tumor-suppressing function in skin, Casp14 was recently shown to be down-regulated in UV-induced skin carcinogenesis [34]. In humans, caspase 14 is mainly found in epidermal cells, in which it can be induced by epigallocatechin-3-gallate, the most abundant tumor-preventive polyphenol in green tea [35]. Unlike human caspase 14, which is a cytokine activator, mouse caspase 14 is a regulator of apoptosis, resembling in enzyme activity and substrate preference apical apoptotic caspases, such as caspase 8 [36]. Considering that activation of caspase 8 has been associated with CDDO-induced killing in human tumor cells [13-15,37], it is conceivable that caspase 14 plays a similar role in apoptosis induction in mouse iMycEμ cells. However, this has not yet been shown.

The drop in Myc protein in both iMycEμ cell lines suggested that CDDO-Im-induced growth inhibition and apoptosis is regulated, in part, at the level of Myc turnover. Stabilization of Myc has been shown to be key in the growth and survival of Myc-induced B-cell neoplasms in Eμ-Myc mice [38,39], a widely used transgenic model system of the human endemic Burkitt lymphoma t(8;14)/mouse plasmacytoma T(12;15) translocation [40]. The precise mechanism by which CDDO-Im down-regulates Myc in iMycEμ cells remains to be elucidated. Given the complexity of Myc protein regulation, this mechanism may involve changes in the PI3K/Akt signaling cascade, specifically in the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and glycogen-3-synthase beta (G3K-3β) [41-45] components of this cascade. Changes in pathways that include the S-phase kinase-associated protein 2 (Skp2) [46,47] and F-box and WD-40 domain protein 7 (Fbxw7) [48] may also play a role.

Considering Myc's dual ability to activate and repress the transcription of countless target genes [23,49], it is possible that the CDDO-Im-induced loss of Myc is responsible, at least in part, for the observed gene expression changes in the two iMycEμ cell lines. According to this hypothesis, the reduction of Myc would relieve the Myc-dependent repression of negatively regulated targets (resulting in their up-regulation) and diminish the activation of positively regulated targets (causing their down-regulation). Of 32 concordantly up-regulated genes in CDDO-Im-treated iMycEμ cells (30 on the Superarray + 2 on the Lymphochip), 9 (28%) genes are known Myc targets: Creb1, Bcl2, Casp8, Casp9, Gadd45a, Hmox1 and Ugt1a1 [50]. Likewise, one of the five (20%) concordantly down-regulated genes detected on the Lymphochip is a validated Myc target: Akt2. Additional studies are required to distinguish a simple association of gene expression change and drop in Myc from a cause-and-effect relationship of Myc levels and gene expression.

Conclusion

CDDO-Im, the C28 imidazolide derivative of CDDO, inhibits tumor cells by a complex mechanism that may rely, in part, on induction of stress responses and down-regulation of Myc. Due to the elusiveness of the cellular targets of CDDO-Im, or its metabolites, the precise molecular mechanism by which the compound affects tumor cells has not yet been elucidated. CDDO-Im is thus at present a promising yet orphan drug candidate for cancer treatment and prevention [1]. A recent study on the collaboration of CDDO-Im with the proteasome inhibitor PS-341 (bortezomib) in apoptosis induction in neoplastic plasma cells has underscored the potential clinical utility of CDDO-Im [5]. The present paper suggests that transgenic mouse models of plasma cell neoplasia, such as the peritoneal PCT that can be readily induced in BALB/c.iMycEμ mice [27], may be helpful to further define the mechanism by which CDDO-Im inhibits plasma cell tumors in human beings.

Methods

CDDO-Im

CDDO-Im was synthesized by Dr. Tadashi Honda (Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH) [51] and provided by Dr. Edward Sausville (Developmental Therapeutics Program, NCI, Bethesda, MD) through the Rapid Access to Intervention Development (RAID) Program. For biological experiments with iMycEμ-1 and-2 cells, the compound was dissolved in DMSO and added to cells in vitro such that the final DMSO concentration did not exceed 0.1% v/v.

Derivation and characterization of iMycEμ-1 and-2 cells

The features and origin of iMycEμ-1 cells have been described elsewhere [21]. The iMycEμ-2 cells were derived from a spontaneous plasmacytoma that arose in an iMycEμ mouse on the mixed genetic background of segregating C57BL/6 and 129/SvJ alleles. Strain iMycEμ develops a high incidence of B cell and plasma cell tumors of different histological types, with plasmacytomas being relatively rare (~20% of tumors). Tissue samples obtained at autopsy were processed for histopathology, which established the diagnosis of plasmacytoma using criteria described in the Bethesda classification of mouse B-cell lineage lymphomas [52]. The iMycEμ-2 cells were maintained in vitro at 37°C and 5% carbon dioxide in RPMI 1640 cell culture medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 200 mM L-glutamine and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Gibco-BRL, Rockville, MD). For cytological analysis, cytofuge specimens were stained according to May-Grünwald-Giemsa and inspected by microscopy. For flow cytometry, single-cell suspensions were stained and analyzed on a FACSort® using the CELLQuest™ software (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). Rat anti-mouse CD16/CD32 was used to block FcγII and FcγIII receptors. Antibodies to mouse CD138 (catalog number 553712), CD40 (553787), Fas (CD90, 554255), IgD (553438) and IgM (53519) were purchased from BD Biosciences.

Western blotting of Myc

Whole cell lysates were obtained by re-suspending pellets of 107 cells at 4°C for 30 min in RIPA buffer (1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 10 ng/ml PMSF, 0.03% aprotinin, 1 μM sodium orthovanadate). The lysates were centrifuged for 6 min at 14,000 g and the supernatants were stored at-70°C as whole cell extract. Protein concentrations of extracts were determined using the BCA kit (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA). For Western blotting, 40 μg of extract was resolved electrophoretically in denaturing 10% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred by electroblotting to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were probed with antibody to Myc (sc-764) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) using titers from 1:1000 to 1:5000. The positions of the proteins were visualized with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Amersham, 1:5000) using the chemiluminescence detection kit from Amersham. To confirm equal loading, the membranes were stripped and re-probed using an antibody specific for β-actin (sc-8432, Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Allele-specific RT-PCR of Myc and MycHis mRNA

For semi-quantitative determination of Myc and MycHis mRNA, total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). The integrity of RNA was verified by electrophoresis. Double stranded cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA, using the AMV Reverse Transcriptase kit (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). A common 5' primer for both MycHis and Myc (5'-TCT CCA CTC ACC AGC ACA AC-3') was combined with a specific 3' primer for MycHis (5'-CCT CGA GTT AGG TCA GTT TA-3') and Myc (5'-ATG GTG ATG GTG ATG ATG AC-3') to distinguish the two messages. Thermal cycling conditions were as follows: 95°C for 5 min (initial template denaturation) followed by 20 cycles of amplification at 57°C (primer annealing), 72°C (extension) and 95°C (melting), each for 1 min. PCR amplification of Aktb cDNA was performed for each sample as a control using the following primer pair: 5'-GCA TTG TTA CCA ACT GGG AC-3' (forward) and 5'-AGG CAG CTC ATA GCT CTT CT-3' (reverse). PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gel and visualized by staining with ethidium bromide.

In some experiments, Myc and MycHis mRNA were determined using real-time, quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR) using the SYBR Green I method on the Light Cycler (Roche) with attendant software for analyzing fluorescence emission data. The reaction volume (20 μl) contained 100 ng cDNA, the Light Cycler Fast Starter mix, 1 mM MgCl2 and primers. Thermal cycling conditions were as follows: 95°C for 10 min (initial template denaturation) followed by 40 cycles of amplification at 57°C (primer annealing), 72°C (extension) and 95°C (melting), each for 1 min. PCR amplification of Gapd cDNA was performed as control.

Proliferation and cell cycle analysis

Proliferation was determined with the help of the "MTS" Cell Titer 96 aqueous non-radioactive cell proliferation assay from Promega (Madison, WI) following the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, 3 × 10 iMycEμ 1 or-2 cells were re-suspended in 100 μl RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 25 μg/ml LPS and placed into 96-well flat-bottom microtiter plates (Costar, Cambridge). After incubation for 20 hrs at 37°C and 5% CO2, 20 μl of MTS/PMS solution was added to each well. The cells were incubated for another 4 hrs and the absorbance at 490 nm was measured using an ELISA reader. For cell cycle analysis, cells were stained with 50 μg/ml propidium iodide in 0.1% sodium citrate and 0.1% Triton X100 and then analyzed on a Beckman Coulter FC500.

Apoptosis assays

Programmed cell death was evaluated with the assistance of the DNA fragmentation assay and FACS analysis of propidium iodide (PI), annexin V, and caspase-3 reactivity. For the detection of nucleosomal DNA fragmentation, DNA was extracted using the Puregene kit (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and fractionated by electrophoresis on 1.2% agarose gels containing ethidium bromide. For the determination of cells with sub-G0/G1 DNA content, cells were re-suspended in PI/Rnase buffer (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) for 20 min at 37°C in the dark, followed by FACS analysis. Annexin-V reactivity was determined with a phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled antibody (BD Pharmingen) in cells co-stained with 7-AAD (7-amino-actinomycin D). This distinguishes dying cells (annexin+AAD-) from dead cells (annexin+AAD+). Activated caspase 3 was determined with a FITC-labeled antibody from BD Pharmingen.

Gene expression profiling on cDNA macroarrays

The relative mRNA expression of genes involved in regulation of apoptosis, cell cycle progression, NFκB signaling, and cellular stress and toxicity responses was analyzed with GEArray (SuperArray Inc., Bethesda, MD) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Cells were treated for 24 hrs with 0.4 mM and 1 mM CDDO-Im, respectively, followed by preparation of total RNA using TriReagent (Sigma). Five μg from each sample were reverse transcribed into 32P-labeled cDNA using MMLV reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI) and 32P-dCTP (NEN, Boston, MA). The resulting cDNA probes were hybridized to gene-specific cDNA fragments spotted in quadruplicates on the GEArray membranes. After stringent washing of the arrays, the signal of the hybridized spots was measured with a STORM PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA) and normalized to the signal of the housekeeping gene Gapd. Array results on six CDDO-Im inducible genes were validated using semi-quantitative RT-PCR.

Gene microarray hybridization and analysis

cDNA made from total RNA (50 μg) from iMycEμ-1 and-2 cells was labeled with cyanine 5-conjugated dUTP (Cy5) and cDNA made from pooled mouse cell line RNA (50 μg) was labeled with cyanine 3-conjugated dUTP (Cy3). Microarray hybridizations were performed on Mouse Lymphochip microarrays [53]. After washing, the slides were scanned using an Axon GenePix 4.0 scanner (Axon Instruments Inc., Union City, CA). After normalization, those elements that failed to meet confidence criteria based on signal intensity and spot quality were excluded from analysis. In addition, data were discarded for any gene for which measurements were missing on >30% of the arrays or were not sequence-verified. The Cy5:Cy3 intensity ratios of the remaining spots were log2 transformed. To compare normal samples, hierarchical cluster analysis was performed using the Gene Cluster and Treeview programs [54].

Plasmacytoma induction in iMycEμ mice treated with CDDO-Im

Transgenic iMycEμ mice on the PCT-susceptible background of BALB/c were fed Purina Mouse Chow (PMI Feeds, St Louis, MO) and acidified water ad libitum. All experiments were performed in a conventional barrier-protected colony under NCI Animal Study Protocol LG-028. PCT were induced with a single i.p. injection of 0.2 ml pristane (Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI) on day 1. Beginning on day 7 post-pristane and continuing throughout the observation period of 60 days, primed mice of this sort (n = 25) were treated with three weekly i.p. injections of either 50 μl CDDO-Im solution (2 mg/ml polyethylene glycol 400 [PEG 400]) (n = 14) or 50 μl vehicle control (PEG 400, n = 11).

PCT were diagnosed on days 30 and 60 post pristane by finding 10 or more hyperchromatic, enlarged, aberrant plasma cells in cytofuged preparations of ascites cells. In mice where there were less than 50 tumor cells per slide, a confirmatory smear was obtained.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

Seong-Su Han determined Superarray gene expression profiles and Myc protein levels; Liangping Peng and Seung-Tae Chung harvested and transplanted tumors, cultured cells, and performed cytological and FACS analyses; Sungho Maeng validated gene array results using RT-PCR; Art Shaffer determined gene expression profiles on mouse Lymphochips; Wendy DuBois conducted the tumor induction study in mice; Michael Sporn provided CDDO-Im and contributed critical insights; and Siegfried Janz designed the study and wrote and approved the article.

Supplementary Material

contains a table of discordantly regulated genes upon treatment with CDDO-Im

contains a table of RT-PCR primers used for gene array validation

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Alexander L. Kovalchuk, NCI, for his help in establishing cell lines; Jae-Hwan Lim, currently at Andong University, South Korea, for performing Western blots; J. Frederic Mushinski, NCI, for reading the paper and making helpful suggestions; and Louis M. Staudt and Beverly A. Mock, both NCI, for support. This research was supported in part by the IntramuralResearch Program of the NIH, NCI, CCR.

Contributor Information

Seong-Su Han, Email: hanse@mail.nih.gov.

Liangping Peng, Email: lp232@georgetown.edu.

Seung-Tae Chung, Email: chungs@mail.nih.gov.

Wendy DuBois, Email: duboisw@dino.nci.nih.gov.

Sung-Ho Maeng, Email: true_vj@hotmail.com.

Arthur L Shaffer, Email: as275s@nih.gov.

Michael B Sporn, Email: Michael.B.Sporn@Dartmouth.EDU.

Siegfried Janz, Email: sj4s@nih.gov.

References

- Honda T, Janosik T, Honda Y, Han J, Liby KT, Williams CR, Couch RD, Anderson AC, Sporn MB, Gribble GW. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of biotin conjugates of 2-cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1,9(11)-dien-28-oic acid for the isolation of the protein targets. J Med Chem. 2004;47:4923–4932. doi: 10.1021/jm049727e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melichar B, Konopleva M, Hu W, Melicharova K, Andreeff M, Freedman RS. Growth-inhibitory effect of a novel synthetic triterpenoid, 2-cyano-3,12-dioxoolean-1,9-dien-28-oic acid, on ovarian carcinoma cell lines not dependent on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma expression. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;93:149–154. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Ni X, Konopleva M, Andreeff M, Duvic M. The novel synthetic oleanane triterpenoid CDDO (2-cyano-3, 12-dioxoolean-1, 9-dien-28-oic acid) induces apoptosis in Mycosis fungoides/Sezary syndrome cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;123:380–387. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue S, Snowden RT, Dyer MJ, Cohen GM. CDDO induces apoptosis via the intrinsic pathway in lymphoid cells. Leukemia. 2004;18:948–952. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan D, Li G, Podar K, Hideshima T, Shringarpure R, Catley L, Mitsiades C, Munshi N, Tai YT, Suh N, Gribble GW, Honda T, Schlossman R, Richardson P, Sporn MB, Anderson KC. The bortezomib/proteasome inhibitor PS-341 and triterpenoid CDDO-Im induce synergistic anti-multiple myeloma (MM) activity and overcome bortezomib resistance. Blood. 2004;103:3158–3166. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konopleva M, Tsao T, Estrov Z, Lee RM, Wang RY, Jackson CE, McQueen T, Monaco G, Munsell M, Belmont J, Kantarjian H, Sporn MB, Andreeff M. The synthetic triterpenoid 2-cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1,9-dien-28-oic acid induces caspase-dependent and -independent apoptosis in acute myelogenous leukemia. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7927–7935. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou W, Liu X, Yue P, Zhou Z, Sporn MB, Lotan R, Khuri FR, Sun SY. c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase-mediated up-regulation of death receptor 5 contributes to induction of apoptosis by the novel synthetic triterpenoid methyl-2-cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1, 9-dien-28-oate in human lung cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7570–7578. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda T, Nakata Y, Kimura F, Sato K, Anderson K, Motoyoshi K, Sporn M, Kufe D. Induction of redox imbalance and apoptosis in multiple myeloma cells by the novel triterpenoid 2-cyano-3,12-dioxoolean-1,9-dien-28-oic acid. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:39–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh N, Roberts AB, Birkey Reffey S, Miyazono K, Itoh S, ten Dijke P, Heiss EH, Place AE, Risingsong R, Williams CR, Honda T, Gribble GW, Sporn MB. Synthetic triterpenoids enhance transforming growth factor beta/Smad signaling. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1371–1376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mix KS, Coon CI, Rosen ED, Suh N, Sporn MB, Brinckerhoff CE. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma-independent repression of collagenase gene expression by 2-cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1,9-dien-28-oic acid and prostaglandin 15-deoxy-delta(12,14) J2: a role for Smad signaling. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:309–318. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh N, Wang Y, Honda T, Gribble GW, Dmitrovsky E, Hickey WF, Maue RA, Place AE, Porter DM, Spinella MJ, Williams CR, Wu G, Dannenberg AJ, Flanders KC, Letterio JJ, Mangelsdorf DJ, Nathan CF, Nguyen L, Porter WW, Ren RF, Roberts AB, Roche NS, Subbaramaiah K, Sporn MB. A novel synthetic oleanane triterpenoid, 2-cyano-3,12-dioxoolean-1,9-dien-28-oic acid, with potent differentiating, antiproliferative, and anti-inflammatory activity. Cancer Res. 1999;59:336–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Place AE, Suh N, Williams CR, Risingsong R, Honda T, Honda Y, Gribble GW, Leesnitzer LM, Stimmel JB, Willson TM, Rosen E, Sporn MB. The novel synthetic triterpenoid, CDDO-imidazolide, inhibits inflammatory response and tumor growth in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:2798–2806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y, Pandey P, Place A, Sporn MB, Gribble GW, Honda T, Kharbanda S, Kufe D. The novel triterpenoid 2-cyano-3,12-dioxoolean-1,9-dien-28-oic acid induces apoptosis of human myeloid leukemia cells by a caspase-8-dependent mechanism. Cell Growth Differ. 2000;11:261–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y, Pandey P, Sporn MB, Datta R, Kharbanda S, Kufe D. The novel triterpenoid CDDO induces apoptosis and differentiation of human osteosarcoma cells by a caspase-8 dependent mechanism. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:1094–1099. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.5.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadheim TA, Suh N, Ganju N, Sporn MB, Eastman A. The novel triterpenoid 2-cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1,9-dien-28-oic acid (CDDO) potently enhances apoptosis induced by tumor necrosis factor in human leukemia cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:16448–16455. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108974200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapillonne H, Konopleva M, Tsao T, Gold D, McQueen T, Sutherland RL, Madden T, Andreeff M. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma by a novel synthetic triterpenoid 2-cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1,9-dien-28-oic acid induces growth arrest and apoptosis in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5926–5939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh WS, Kim YS, Schimmer AD, Kitada S, Minden M, Andreeff M, Suh N, Sporn M, Reed JC. Synthetic triterpenoids activate a pathway for apoptosis in AML cells involving downregulation of FLIP and sensitization to TRAIL. Leukemia. 2003;17:2122–2129. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hail NJ, Konopleva M, Sporn M, Lotan R, Andreeff M. Evidence supporting a role for calcium in apoptosis induction by the synthetic triterpenoid 2-cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1,9-dien-28-oic acid (CDDO) J Biol Chem. 2004;279:11179–11187. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312758200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SS, Kim JS, Tessarollo L, Owens JD, Peng L, Han SS, Tae Chung S, Torrey TA, Cheung WC, Polakiewicz RD, McNeil N, Ried T, Mushinski JF, Morse HC, Janz S. Insertion of c-Myc into Igh induces B-cell and plasma-cell neoplasms in mice. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1306–1315. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung WC, Kim JS, Linden M, Peng L, Van Ness B, Polakiewicz RD, Janz S. Novel targeted deregulation of c-Myc cooperates with Bcl-X(L) to cause plasma cell neoplasms in mice. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1763–1773. doi: 10.1172/JCI200420369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han SS, Shaffer AL, Peng L, Chung ST, Lim JH, Maeng S, Kim JS, McNeil N, Ried T, Staudt LM, Janz S. Molecular and cytological features of the mouse B-cell lymphoma line iMycEmu-1. Mol Cancer. 2005;4:40. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-4-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Han S, Park S, McNeil N, Janz S. Plasma cell tumour progression in iMyc(Emicro) gene-insertion mice. J Pathol. 2006;209:44–55. doi: 10.1002/path.1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levens DL. Reconstructing MYC. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1071–1077. doi: 10.1101/gad.1095203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott S, Hays E, Mayor M, Sporn M, Vincenti M. The triterpenoid CDDO inhibits expression of matrix metalloproteinase-1, matrix metalloproteinase-13 and Bcl-3 in primary human chondrocytes. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003;5:R285–91. doi: 10.1186/ar792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh A, Eisen M, Davis RE, Ma C, Sabet H, Tran T, Powell JI, Yang L, Marti GE, Moore DT, Hudson JRJ, Chan WC, Greiner T, Weisenburger D, Armitage JO, Lossos I, Levy R, Botstein D, Brown PO, Staudt LM. The lymphochip: a specialized cDNA microarray for the genomic-scale analysis of gene expression in normal and malignant lymphocytes. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1999;64:71–78. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1999.64.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouse Lymphochip gene microarray: http://lymphochipnihgov/ShafferPCfactors.

- Park SS, Shaffer AL, Kim JS, duBois W, Potter M, Staudt LM, Janz S. Insertion of Myc into Igh accelerates peritoneal plasmacytomas in mice. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7644–7652. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieter MZ, Freshwater SL, Miller ML, Shertzer HG, Dalton TP, Nebert DW. Pharmacological rescue of the 14CoS/14CoS mouse: hepatocyte apoptosis is likely caused by endogenous oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;35:351–367. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(03)00273-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda K, Lin J, Okubo S, Akazawa-Kudoh S, Kajinami K, Kanemitsu S, Tsugawa H, Kanda T, Matsui S, Takekoshi N. Transient glucose deprivation causes upregulation of heme oxygenase-1 and cyclooxygenase-2 expression in cardiac fibroblasts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;36:821–830. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan KT, Ni H, Brown HR, Yoon L, Qualls CWJ, Crosby LM, Reynolds R, Gaskill B, Anderson SP, Kepler TB, Brainard T, Liv N, Easton M, Merrill C, Creech D, Sprenger D, Conner G, Johnson PR, Fox T, Sartor M, Richard E, Kuruvilla S, Casey W, Benavides G. Application of cDNA microarray technology to in vitro toxicology and the selection of genes for a real-time RT-PCR-based screen for oxidative stress in Hep-G2 cells. Toxicol Pathol. 2002;30:435–451. doi: 10.1080/01926230290105613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Koza-Taylor PH, DiMattia DA, Hames L, Fu H, Dragnev KH, Turi T, Beebe JS, Freemantle SJ, Dmitrovsky E. Microarray analysis uncovers retinoid targets in human bronchial epithelial cells. Oncogene. 2003;22:4924–4932. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashman JR. The role of flavin-containing monooxygenases in drug metabolism and development. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2003;6:486–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid JM, Walker DL, Miller JK, Benson LM, Tomlinson AJ, Naylor S, Blajeski AL, LoRusso PM, Ames MM. The metabolism of pyrazoloacridine (NSC 366140) by cytochromes p450 and flavin monooxygenase in human liver microsomes. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:1471–1480. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-0557-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rundhaug JE, Hawkins KA, Pavone A, Gaddis S, Kil H, Klein RD, Berton TR, McCauley E, Johnson DG, Lubet RA, Fischer SM, Aldaz CM. SAGE profiling of UV-induced mouse skin squamous cell carcinomas, comparison with acute UV irradiation effects. Mol Carcinog. 2005;42:40–52. doi: 10.1002/mc.20064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu S, Yamamoto T, Borke J, Walsh DS, Singh B, Rao S, Takaaki K, Nah-Do N, Lapp C, Lapp D, Foster E, Bollag WB, Lewis J, Wataha J, Osaki T, Schuster G. Green Tea Polyphenol-Induced Epidermal Keratinocyte Differentiation Is Associated with Coordinated Expression of p57/KIP2 and Caspase 14. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312:884–890. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.076075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikolajczyk J, Scott FL, Krajewski S, Sutherlin DP, Salvesen GS. Activation and substrate specificity of caspase-14. Biochemistry. 2004;43:10560–10569. doi: 10.1021/bi0498048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen IM, Kitada S, Schimmer A, Kim Y, Zapata JM, Charboneau L, Rassenti L, Andreeff M, Bennett F, Sporn MB, Liotta LD, Kipps TJ, Reed JC. The triterpenoid CDDO induces apoptosis in refractory CLL B cells. Blood. 2002;100:2965–2972. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Arsura M, Wu M, Duyao M, Buckler AJ, Sonenshein GE. Role of Rel-related factors in control of c-myc gene transcription in receptor-mediated apoptosis of the murine B cell WEHI 231 line. JExpMed. 1995;181:1169–1177. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.3.1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grumont RJ, Strasser A, Gerondakis S. B Cell Growth Is Controlled by Phosphatidylinosotol 3-Kinase-Dependent Induction of Rel/NF-kappaB Regulated c-myc Transcription. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1283–1294. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00779-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams JM, Harris AW, Pinkert CA, Corcoran LM, Alexander WS, Cory S, Palmiter RD, Brinster RL. The c-myc oncogene driven by immunoglobulin enhancers induces lymphoid malignancy in transgenic mice. Nature. 1985;318:533–538. doi: 10.1038/318533a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galmozzi E, Casalini P, Iorio MV, Casati B, Olgiati C, Menard S. HER2 signaling enhances 5'UTR-mediated translation of c-Myc mRNA. J Cell Physiol. 2004;200:82–88. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Gera J, Hu L, Hsu JH, Bookstein R, Li W, Lichtenstein A. Enhanced sensitivity of multiple myeloma cells containing PTEN mutations to CCI-779. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5027–5034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gera JF, Mellinghoff IK, Shi Y, Rettig MB, Tran C, Hsu JH, Sawyers CL, Lichtenstein AK. AKT activity determines sensitivity to mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors by regulating cyclin D1 and c-myc expression. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:2737–2746. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309999200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh E, Cunningham M, Arnold H, Chasse D, Monteith T, Ivaldi G, Hahn WC, Stukenberg PT, Shenolikar S, Uchida T, Counter CM, Nevins JR, Means AR, Sears R. A signalling pathway controlling c-Myc degradation that impacts oncogenic transformation of human cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:308–318. doi: 10.1038/ncb1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez-Sola D, Dalla-Favera R. PINning down the c-Myc oncoprotein. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:288–289. doi: 10.1038/ncb0404-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Herbst A, Tworkowski KA, Salghetti SE, Tansey WP. Skp2 regulates Myc protein stability and activity. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1177–1188. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00173-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von der Lehr N, Johansson S, Wu S, Bahram F, Castell A, Cetinkaya C, Hydbring P, Weidung I, Nakayama K, Nakayama KI, Soderberg O, Kerppola TK, Larsson LG. The F-box protein Skp2 participates in c-Myc proteosomal degradation and acts as a cofactor for c-Myc-regulated transcription. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1189–1200. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00193-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welcker M, Orian A, Jin J, Grim JA, Harper JW, Eisenman RN, Clurman BE. The Fbw7 tumor suppressor regulates glycogen synthase kinase 3 phosphorylation-dependent c-Myc protein degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9085–9090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402770101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhikary S, Eilers M. Transcriptional regulation and transformation by Myc proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:635–645. doi: 10.1038/nrm1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myc target gene database: http://www.myccancergene.org.

- Honda T, Honda Y, Favaloro FGJ, Gribble GW, Suh N, Place AE, Rendi MH, Sporn MB. A novel dicyanotriterpenoid, 2-cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1,9(11)-dien-28-onitrile, active at picomolar concentrations for inhibition of nitric oxide production. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2002;12:1027–1030. doi: 10.1016/S0960-894X(02)00105-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse HC, Anver MR, Fredrickson TN, Haines DC, Harris AW, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Kogan SC, MacLennan IC, Pattengale PK, Ward JM. Bethesda proposals for classification of lymphoid neoplasms in mice. Blood. 2002;100:246–258. doi: 10.1182/blood.V100.1.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer AL, Yu X, He Y, Boldrick J, Chan EP, Staudt LM. BCL-6 represses genes that function in lymphocyte differentiation, inflammation, and cell cycle control. Immunity. 2000;13:199–212. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)00020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer AL, Shapiro-Shelef M, Iwakoshi NN, Lee AH, Qian SB, Zhao H, Yu X, Yang L, Tan BK, Rosenwald A, Hurt EM, Petroulakis E, Sonenberg N, Yewdell JW, Calame K, Glimcher LH, Staudt LM. XBP1, downstream of Blimp-1, expands the secretory apparatus and other organelles, and increases protein synthesis in plasma cell differentiation. Immunity. 2004;21:81–93. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

contains a table of discordantly regulated genes upon treatment with CDDO-Im

contains a table of RT-PCR primers used for gene array validation